Chapter 296: Battle of Midway:

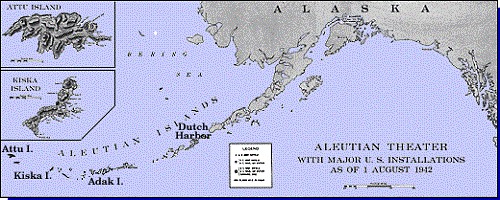

After expanding the war in the Pacific to include Western outposts, the Japanese Empire

re had ttained its initial strategic goals quickly, taking the Philippines, Malaya, Singapore, Guinea, Burma Dutch East Indies, the latter, with its vital oil resources, was particularly important to Japan. Because of this, preliminary planning for a second phase of operations commenced as early as December 1941. There were strategic disagreements between the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) and Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN), and infighting between the Navy's Imperial General Headquartes and Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto's Combined Fleet, and a follow-up strategy was not formed until March 1942. Admiral Yamamoto finally succeeded in winning the bureaucratic struggle with a thinly veiled threat to resign, after which his plan for the Central Pacific was adopted. Yamamoto's primary strategic goal was the elimination of America's carrier forces, which he regarded as the principal threat to the overall Pacific campaign. Believing them to still be of danger Yamamoto hoped that a air attack on the main U.S. Naval base at Pearl Harbor would induce all of the American fleet to sail out to fight, including the carriers and could maybe take a few of them out in the initial attack by surprise. But to get to Hawaii the flank and back needed to be defended, by taking the Aleutian Islands in the north and Midway in the South of their route to Pearl Harbor.

Midway, a tiny atoll at the extreme northwest end of the Hawaiian Island chain, approximately 1,300 miles (1,100 nautic miles; 2,100 kilometres) from Oahu. This meant that Midway was outside the effective range of almost all of the American aircraft stationed on the main Hawaiian islands. The Japanese felt the Americans would consider Midway a vital outpost of Pearl Harbor and would therefore be compelled to defend it vigorously. In addition to serving as a seaplane and submarine base, (extending their radius of operations by 1,200 miles/ 1,900 km), Midway's airstrips also served as a forward staging point for bomber attacks on Wake Island, weakening the Japanese Outer Line of Defence there. Typical of Japanese naval planning during Second Great War, Yamamoto's battle plan for taking Midway (named Operation MI) was exceedingly complex. It required the careful and timely coordination of multiple battle groups over hundreds of miles of open sea. His design was also predicated on optimistic intelligence suggesting that USS Saratoga, was the only carriers available to the U.S. Pacific Fleet. During the Battle of the Coral Sea one month earlier, USS Yorktown and USS Enterprise had been suffered considerable damage such that the Japanese believed they had been lost. However, following hasty repairs at Pearl Harbor, Yorktown and Enterprise (being chosen as the USS Wasp was late from the Atlantic and would not arrive in time, therefore it took Enterprise's place in the South Pacific, while Enterprise was used north at Midway) sortied and would go on to play a critical role in the discovery and eventual destruction of the Japanese fleet carriers at Midway. Finally, much of Yamamoto's planning, coinciding with the general feeling among the Japanese leadership at the time, was based on a gross misjudgment of American morale, which was believed to be already debilitated from the string of Japanese victories in the preceding months. Yamamoto felt deception would be required to lure the U.S. fleet into a fatally compromised situation. To this end, he dispersed his forces so that their full extent (particularly his battleships) would be concealed from the Americans prior to battle. Critically, Yamamoto's supporting battleships and cruisers trailed Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo's carrier force by several hundred miles. They were intended to come up and destroy whatever elements of the U.S. fleet might come to Midway's defense once Nagumo's carriers had weakened them sufficiently for a daylight gun battle; this tactic was typical of the battle doctrine of most major navies at the time.

What Yamamoto did not know was that the U.S. had broken the main Japanese naval code (dubbed JN-25 by the Americans), divulging many details of his plan to the enemy. His emphasis on dispersal also meant none of his formations were in a position to support each other. For instance, despite the fact that Nagumo's carriers were expected to carry out strikes against Midway and bear the brunt of American counterattacks, the only warships in his fleet larger than the screening force of twelve destroyers were four Kongo-class fast battleships, four heavy cruisers, and two light cruiser. By contrast, Yamamoto and Kondo had between them four light carriers, ten battleships, eight heavy cruisers, and four light cruisers, that would later help take Midway. The light carriers of the trailing forces and Yamamoto's six battleships were unable to keep pace with the carriers of the Kido Butai and so could not have sailed in company with them. The distance between Yamamoto and Kondo's forces and Nagumo's carriers had grave implications during the battle: the invaluable reconnaissance capability of the scout planes, balloons and small airships carried by the cruisers and carriers, as well as the additional antiaircraft capability of the cruisers and the other four battleships of the Kongō-class in the trailing forces, was denied to Nagumo.

To do battle with an enemy expected to muster four or five carriers, Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief, Pacific Ocean Areas, needed every available U.S. flight deck. He already had Vice Admiral William Halsey's two-carrier (Saratoga and Yorktown) task force at hand, though Halsey was stricken with severe dermatitis and had to be replaced by Rear Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, Halsey's escort commander. Nimitz also hurriedly recalled Rear Admiral Frank Jack Fletcher's task force, including the carrier Enterprise, from the South West Pacific Area. Despite estimates that Yorktown, damaged in the Battle of Coral Sea and Enterprise damaged as well, would require several months of repairs at Puget Sound Naval Shipyards, her elevators were intact and her flight deck largely so. The Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard worked around the clock, and in 72 hours they were restored to a battle-ready state, judged good enough for two or three weeks of operations, as Nimitz required. Yorktowns flight deck was patched, and whole sections of internal frames were cut out and replaced. Repairs continued even as she sortied, with work crews from the repair ship USS Vestal, still aboard. Enterprise and Yorktowns partially depleted air groups were rebuilt using whatever planes and pilots could be found. Scouting Five (VS-5) was replaced with Bombing Three (VB-3) from USS Saratoga. Torpedo Five (VT-5) was also replaced by Torpedo Three (VT-3). Also Fighting Three (VF-3) was reconstituted to replace VF-42 with sixteen pilots from VF-42 and eleven pilots from VF-3 with Lieutenant Commander John S. “Jimmy” Thach in command. Some of the aircrew were inexperienced, which may have contributed to an accident in which Thach's executive officer Lt Cmndr Donald Lovelace was killed. Despite efforts to get USS Wasp to Midway from it's position in the South Pacific, she would not make it in time.

The Japanese on the other hand would soon learn that their IJN crew training program, would show signs of being unable to replace losses after Midway, together with other hard lessons. The First Carrier Strike Force (Akagi, Kaga, Soryu and Hiryu) sailed with 265 available aircraft (plus 61 reserves/ spare ones) on the four carriers (66 on Akagi + 25 reserves, 72 on Kaga +18 in storage, 64 on Hiryū +9 spares and 63 on Sōryū +9 reserves). The main Japanese carrier-borne strike aircraft were the D3A1 "Val" dive bomber and the B5N2 "Kate", which was used either as a torpedo bomber or as a level bomber. The main carrier fighter was the fast and highly maneuverable A6M “Zero”. Many of the aircraft being used during the June 1942 operations had been operational since late November 1941 and, although they were well-maintained, many were almost worn out and had become increasingly unreliable. These factors meant all carriers of the Kido Butai had fewer aircraft to replace the losses that would occur at Midway during their attack anyway. In addition, Nagumo's carrier force suffered from several defensive deficiencies which gave it, in Mark Peatti's words, a “glass jaw”: it could throw a punch but couldn't take one." Japanese carrier anti-aircraft guns and associated fire control systems had several design and configuration deficiencies which limited their effectiveness, a reality accepted by the Japanese only after the disaster of Midway that would now come. The IJN's fleet combat air patrol (CAP) consisted of too few fighter aircraft. Poor radio communications with the fighter aircraft inhibited effective command and control of the CAP. The carriers' escorting warships were deployed as visual scouts in a ring at long range, not as close anti-aircraft escorts, as they lacked training, doctrine, and sufficient anti-aircraft guns.

Japanese strategic scouting arrangements prior to the battle were also in disarray. A picket line of Japanese submarines was late getting into position (partly because of Yamamoto's haste), which let the American carriers reach their assembly point northeast of Midway (known as "Point Luck") without being detected. A second attempt at reconnaissance, using four-engine H8K "Emily" flying boats to scout Pearl Harbor prior to the battle and detect whether the American carriers were present, part of Operation K, was thwarted when Japanese submarines assigned to refuel the search aircraft discovered that the intended refueling point, a hitherto deserted bay off French Frigate Shoals, was now occupied by American warships, because the Japanese had carried out an identical mission in February. Thus, Japan was deprived of any knowledge concerning the movements of the American carriers immediately before the battle. Japanese radio intercepts did notice an increase in both American submarine activity and message traffic. This information was in Yamamoto's hands prior to the battle. Japanese plans were not changed; Yamamoto, at sea in Yamato, assumed Nagumo had received the same signal from Tokyo, and did not communicate with him by radio, so as not to reveal his position. These messages were, also received by Nagumo before the battle began, Nagumo did not alter his plans or take additional precautions.

Admiral Nimitz had one critical advantage: US cryptanalysts had partially broken the Japanese Navy's JN-25b code. Since early 1942, the US had been decoding messages stating that there would soon be an operation at objective "AF". It was initially not known where "AF" was, but Commander Joseph Rochefort and his team at Station HYPO were able to confirm that it was Midway: Captain Wilfred Holmes devised a ruse of telling the base at Midway (by secure undersea cable) to broadcast an uncoded radio message stating that Midway's water purification system had broken down. Within 24 hours, the code breakers picked up a Japanese message that "AF was short on water". No Japanese radio operators who intercepted the message seemed concerned that the Americans were broadcasting uncoded that a major naval installation close to the Japanese threat ring was having a water shortage, which could have tipped off Japanese intelligence officers that it was a deliberate attempt at deception. HYPO was also able to determine the date of the attack as either 4 or 5 June, and to provide Nimitz with a complete IJN order of battle. Japan had a new codebook, but its introduction had been delayed, enabling HYPO to read messages for several crucial days; the new code, which would take several days to be cracked, came into use on 24 May, but the important breaks had already been made.

As a result, the Americans entered the battle with a very good picture of where, when, and in what strength the Japanese would appear. Nimitz knew that the Japanese had negated their numerical advantage by dividing their ships into four separate task groups, all too widely separated to be able to support each other. This dispersal resulted in few fast ships being available to escort the Carrier Striking Force, reducing the number of anti-aircraft guns protecting the carriers. Nimitz calculated that the aircraft on his three carriers, plus those on Midway Island, gave the U.S. rough parity with Yamamoto's four carriers, mainly because American carrier air groups were larger than Japanese ones. The Japanese, by contrast, remained mainly unaware of their opponent's true strength and dispositions until the battle began. At about 09:00 on 3 June, Ensign Jack Reid, piloting a PBY from U.S. Navy patrol squadron VP-44 spotted the Japanese Occupation Force 500 nautical miles (580 miles; 930 kilometres) to the west-southwest of Midway. He mistakenly reported this group as the Main Force. Nine B-17s took off from Midway at 12:30 for the first air attack. Three hours later, they found Tanaka's transport group 570 nautical miles (660 miles; 1,060 kilometres) to the west.

Under heavy anti-aircraft fire, they dropped their bombs. Although their crews reported hitting 4 ships, none of the bombs actually hit anything and no significant damage was inflicted. But thanks to their own radar, Balloon Battalion and their Balloon and small Airship scouts the Japanese gained a first hind at the American positions. Early the following morning, the Japanese oil tanker Akebono Maru sustained the first hit when a torpedo from an attacking PBY struck her around 01:00. This was the only successful air-launched torpedo attack by the U.S. during the entire battle.

At 04:30 on 4 June, Nagumo launched his initial attack on Midway itself, consisting of 36 Aichi D3A dive bombers and 36 Nakajima B5N torpedo bombers, escorted by 36 Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters. At the same time, he launched his 8 search aircraft together with smaller scout balloons and even two small scout airships. Japanese reconnaissance arrangements were flimsy, with too few aircraft to adequately cover the assigned search areas, laboring under poor weather conditions to the northeast and east of the task force. As Nagumo's bombers and fighters were taking off, 11 PBYs were leaving Midway to run their search patterns. At 05:34, a PBY reported sighting 2 Japanese carriers and another spotted the inbound airstrike 10 minutes later. Midway's radar picked up the enemy at a distance of several miles, and interceptors were scrambled. Unescorted bombers headed off to attack the Japanese carriers, their fighter escorts remaining behind to defend Midway. At 06:20, Japanese carrier aircraft bombed and heavily damaged the U.S. base. Midway-based Marine fighters led by Major Floyd B. Parks, which included 6 F4Fs and 20 F2As,

] intercepted the Japanese and suffered heavy losses, though they managed to destroy 4 B5Ns, as well as a single A6M. Within the first few minutes, 2 F4Fs and 13 F2As were destroyed, while most of the surviving U.S. planes were damaged, with only 2 remaining airworthy. American anti-aircraft fire was intense and accurate, destroying 3 additional Japanese aircraft and damaging many more. Of the 108 Japanese aircraft involved in this attack, 11 were destroyed (including 3 that ditched), 14 were heavily damaged, and 29 were damaged to some degree. The initial Japanese attack did not succeed in neutralizing Midway: American bombers could still use the airbase to refuel and attack the Japanese invasion force, and most of Midway's land-based defenses were intact. Japanese pilots reported to Nagumo that a second aerial attack on Midway's defenses would be necessary if troops were to go ashore by 7 June.

Having taken off prior to the Japanese attack, American bombers based on Midway made several attacks on the Japanese carrier force. These included 6 Grumman Avengers, detached to Midway from Saratoga VT-8 (Midway was the combat debut of both VT-8 and the TBF); Marine Scout-Bombing Squadron 241 (VMSB-241), consisting of 11 SB2U-3s and 16 SBDs, plus 4 USAAF B-26s of the 18th Reconnaissance and 69th Bomb Squadrons armed with torpedoes, and 15 B-17s of the 31st, 72nd and 431st Bomb Squadrons. The Japanese repelled these attacks, losing 3 fighters while destroying 5 TBFs, 2 SB2Us, 8 SBDs, and 2 B-26s. Among the dead was Major Lofton R. Henderson of VMSB-241, killed while leading his inexperienced Dauntless squadron into action. One B-26, after being seriously damaged by anti-aircraft fire, made a suicide run on Akagi. Making no attempt to pull out of its run, the aircraft narrowly missed crashing directly into the carrier's bridge, which could have killed Nagumo and his command staff. This experience would later also help create the Japanese tactic of Kamikaze attacks with their aircraft. The attack also helped to stop Nagumo's determination to launch another attack on Midway, in direct violation of Yamamoto's order to keep the reserve strike force armed for anti-ship operations, as the Japanese now were sure where the Japanese carriers had to be stationed thanks to their airship scouting.

In accordance with Japanese carrier doctrine at the time, Admiral Nagumo had kept half of his aircraft in reserve. These comprised two squadrons each of dive bombers and torpedo bombers. The dive bombers were as yet unarmed. The torpedo bombers were armed with torpedoes should any American warships be located. While the morning flight leader's recommendation of a second strike at Midway, Nagumo and Yamamoto realized that destroying the American carriers had priority before any further operation against Midway. Nagumo quickly demanded that the scout planes ascertain the composition of the American force. 20–40 minutes later at 7:20 the scout finally radioed the presence of a single carrier in the American force. This was one of the carriers from Task Force 16. The other two carrier was not sighted. Rear Admiral Tamon Yamaguchi, leading Carrier Division 2 (Hiryu and Soryu), recommended that Nagumo strike immediately with the forces at hand: 18 Aichi D3A1 dive bombers each on Sōryū and Hiryū, and half the ready cover patrol aircraft. Nagumo's opportunity to hit the American ships would later be limited by the soon imminent return of his Midway strike force. The Japanese used this opportunity to position ("spot") their reserve planes on the flight deck for launch. Spotting his flight decks and launching aircraft took a little over 30 minutes until 8:10. By spotting and launching immediately, Nagumo also committing some of his reserve to battle without proper anti-ship armament, and likely without fighter escort; indeed, he had just witnessed how easily unescorted American bombers had been shot down. Japanese carrier doctrine preferred the launching of fully constituted strikes rather than piecemeal attacks. But with confirmation of whether the American force included carriers, Nagumo's reaction was logical to strike them as soon as possible. The arrival of another land-based American air strike at 07:53 gave weight to the need to attack the island again, but it would take time to refit the Japanese planes for such a mission. In the end, Nagumo decided to launch the Japanese second strike force against the American carrier, then wait for his first strike force to land, then launch the reserve together with them for a second run on Midway.

Fletcher's carriers meanwhile had launched their planes beginning at 07:00 (with Saratoga, and Enterprise having completed launching by 07:55, but Yorktown not until 09:08), so the aircraft that would deliver the crushing blow were already on their way. Fletcher, in overall command aboard Saratoga, and benefiting from PBY sighting reports from the early morning, ordered Spruance to launch against the Japanese as soon as was practical, while initially holding Yorktown in reserve in case any other Japanese carriers were found. Spruance judged that, though the range was extreme, a strike could succeed and gave the order to launch the attack. He then left Halsey's Chief of Staff, Captain Miles Browning, to work out the details and oversee the launch. The carriers had to launch into the wind, so the light southeasterly breeze would require them to steam away from the Japanese at high speed. Browning therefore suggested a launch time of 07:00, giving the carriers an hour to close on the Japanese at 25 knots (46 km/h; 29 mph). This would place them at about 155 nautical miles (287 km; 178 mi) from the Japanese fleet, assuming it did not change course. The first plane took off from Spruance's carriers Saratoga and Enterprise a few minutes after 07:00 Fletcher, upon completing his own scouting flights, followed suit at 08:00 from Yorktown.

Fletcher, along with Yorktown's commanding officer, Captain Elliott Buckmaster, and their staffs, had acquired first-hand experience in organizing and launching a full strike against an enemy force in the Coral Sea, but there was no time to pass these lessons on to Saratoga and Enterprise which were tasked with launching the first strike. Spruance ordered the striking aircraft to proceed to target immediately, rather than waste time waiting for the strike force to assemble, since neutralizing enemy carriers was the key to the survival of his own task force. That was a major difference to the Japanese Striking Force that waited until 8:10 until they all were assembled for a combined attack run. While the Japanese were able to launch 108 aircraft in just seven minutes, it took Saratoga and Enterprise over an hour to launch 117. Spruance judged that the need to throw something at the enemy as soon as possible was greater than the need to coordinate the attack by aircraft of different types and speeds (fighters, bombers, and torpedo bombers). Accordingly, American squadrons were launched piecemeal and proceeded to the target in several different groups. It was accepted that the lack of coordination would diminish the impact of the American attacks and increase their casualties, but Spruance calculated that this was worthwhile, since keeping the Japanese under aerial attack impaired their ability to launch a counterstrike (Japanese tactics preferred fully constituted attacks), and he gambled that he would find Nagumo with his flight decks at their most vulnerable.

American carrier aircraft had difficulty locating the target, despite the positions they had been given. The strike from Saratoga, led by Commander Stanhope C. Ring, followed an incorrect heading of 265 degrees rather than the 240 degrees indicated by the contact report. As a result, Air Group Eight's dive bombers missed the Japanese carriers. Torpedo Squadron (VT-8, from Hornet), led by Lieutenant Commander John C. Waldron, broke formation from Ring and followed the correct heading. The 10 F4Fs from Enterprise ran out of fuel and had to ditch. Waldron's squadron sighted the enemy carriers and began attacking at 09:20, followed at 09:40 by VT-6 from Yorktown, whose Wildcat fighter escorts lost contact, ran low on fuel, and had to turn back. Without fighter escort, all 15 TBD Devastators of VT-8 were shot down without being able to inflict any damage. Ensign George H. Gay, Jr. was the only survivor of the 30 aircrew of VT-8. VT-6 lost 10 of its 14 Devastators, and 10 of 12 Devastators from Enterprise's VT-3 (who attacked at 10:10) were shot down with no hits to show for their effort, thanks in part to the abysmal performance of their unimproved Mark 13 torpedoes Midway was the last time the TBD Devastator was used in combat.

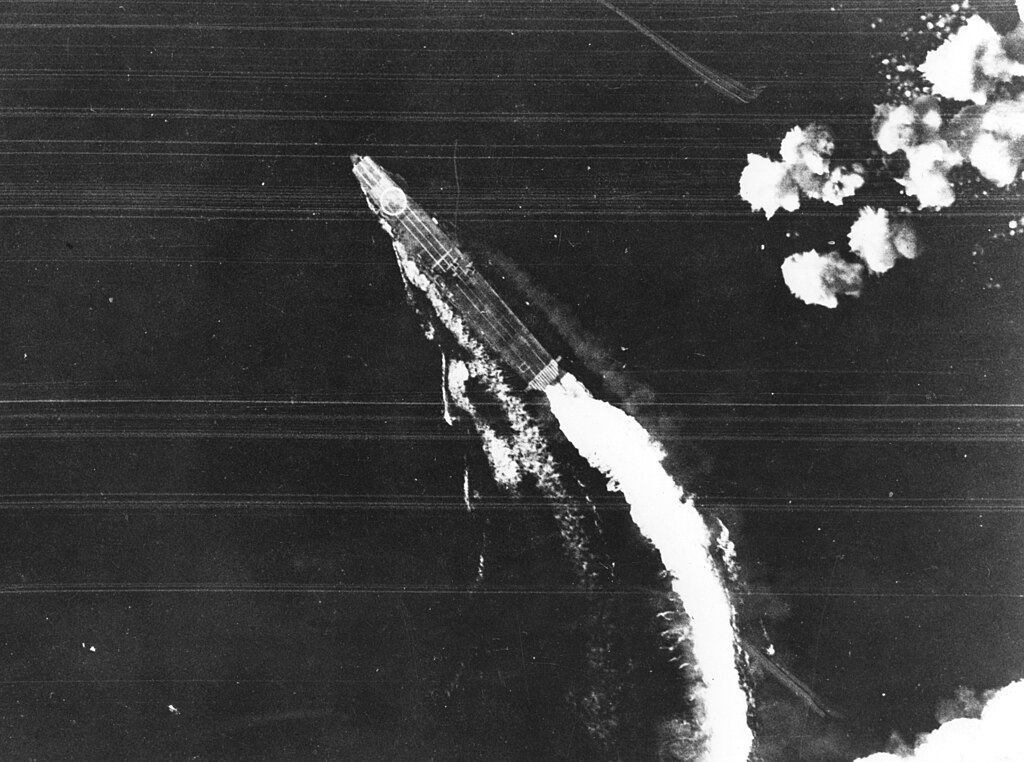

The Japanese combat air patrol, flying Mitsubishi A6M2 Zeros, made short work of the unescorted, slow, under-armed TBDs. A few TBDs managed to get within a few ship-lengths range of their targets before dropping their torpedoes—close enough to be able to strafe the enemy ships and force the Japanese carriers to make sharp evasive maneuvers—but all of their torpedoes either missed or failed to explode. Remarkably, senior Navy and Bureau of Ordnance officers never questioned why half a dozen torpedoes, released so close to the Japanese carriers, produced no results. The performance of American torpedoes in the early months of the war was scandalous, as shot after shot missed by running directly under the target (deeper than intended), prematurely exploded, or hit targets (sometimes with an audible clang) and failed to explode at all. At 9:10 the first Japanese planes reached the Enterprise and started to bomb and torpedo the carrier. Some were shot down by American fighters, but a few actually hid and damaged the carrier. The attack consisted of 36 D3As and 12 fighter escorts, followed the way of the incoming American aircraft to attacked the first carrier they encountered, Enterprise, hitting her with three bombs, which blew a hole in the deck, snuffed out all but one of her boilers, and destroyed one anti-aircraft mount. Damage control parties were able to temporarily patch the flight deck and restore power to several boilers within an hour, giving her a speed of 19 knots (35 km/h; 22 mph) and enabling her to resume air operations. Thirteen Japanese dive bombers and three escorting fighters were lost in this attack (two escorting fighters turned back early after they were damaged attacking some of Yorktown's SBDs returning from their attack on the Japanese carriers). Approximately one hour later at 10:08, the Japanese second attack wave, consisting of ten B5Ns and six escorting A6Ms, arrived over Enterprise; the repair efforts had been so effective that the Japanese pilots assumed that Enterprise must be a different, undamaged carrier. They attacked, crippling Enterprise with two torpedoes; she lost all power and developed a 23-degree list to port. Five torpedo bombers and two fighters were shot down in this attack. News of the two strikes, with the mistaken reports that each had sunk an American carrier, greatly improved Japanese morale. The surviving aircraft were all recovered aboard and despite the heavy losses, the Japanese believed that they could securely strike against what they believed to be the only remaining American carrier by then.

Despite their failure to score any hits, the American torpedo attacks achieved three important results. First, the poor control of the Japanese combat air patrol (CAP) meant they were out of position for subsequent attacks. Second, many of the Zeros ran low on ammunition and fuel. The appearance of a third torpedo plane attack from the southeast by VT-3 from Yorktown at 10:00 very quickly drew the majority of the Japanese CAP to the southeast quadrant of the fleet. Better discipline, and the employment of a greater number of Zeroes for the CAP might have enabled Nagumo to prevent (or at least mitigate) the damage caused by the coming American attacks. By chance, at the same time VT-3 was sighted by the Japanese, three squadrons of SBDs from Enterprise and Saratoga were approaching from the southwest and northeast. The Saratoga squadron (VB-3) had flown just behind VT-3, but elected to attack from a different course. The two squadrons from Enterprise (VB-6 and VS-6) were running low on fuel because of the time spent looking for the enemy. Air Group Commander C. Wade McClusky, Jr. decided to continue the search, and by good fortune spotted the wake of the Japanese destroyer Arashi, steaming at full speed to rejoin Nagumo's carriers after having unsuccessfully dept-charged U.S. Submarine Nautilus, which had unsuccessfully attacked the battleship Kirishima. Some bombers were lost from fuel exhaustion before the attack commenced. McClusky's decision to continue the search and all American dive-bomber squadrons (VB-6, VS-6 and VB-3) arrived almost simultaneously at the perfect time, locations and altitudes to attack. Most of the Japanese CAP was focusing on the torpedo planes of VT-3 and were out of position, armed Japanese strike aircraft filled the hangar decks, fuel hoses snaked across the decks as refueling operations were hastily being completed, and the repeated change of ordnance meant that bombs and torpedoes were stacked around the hangars, rather than stowed safely in the magazines, making the Japanese carriers extraordinarily vulnerable.

Beginning at 10:22, the two squadrons of air group split up with the intention of sending one squadron each to attack Kaga and Akagi. A miscommunication caused both of the squadrons to dive at the Kaga. Recognizing the error, Lieutenant Richard Halsey Best and his two wingmen were able to pull out of their dives and, after judging that Kaga was doomed, headed north to attack Akagi. Coming under an onslaught of bombs from almost two full squadrons, Kaga sustained four or five direct hits, which caused heavy damage and started multiple fires. One of the bombs landed near the bridge, killing Captain Jisaku Okada and most of the ship's senior officers. Several minutes later, Best and his two wingmen dove on the Akagi. Although Akagi sustained only one direct hit (almost certainly dropped by Lieutenant Best), it proved to be a fatal blow: the bomb struck the edge of the mid-ship deck elevator and penetrated to the upper hangar deck, where it exploded among the armed and fueled aircraft in the vicinity. Nagumo's chief of staff, Ryunosuke Kusada, recorded "a terrific fire ... bodies all over the place ... Planes stood tail up, belching livid flames and jet-black smoke, making it impossible to bring the fires under control." Another bomb exploded under water very close astern; the resulting geyser bent the flight deck upward "in grotesque configurations" and caused crucial rudder damage.

Simultaneously, Yorktown's VB-3, commanded by Max Leslie, went for Sōryū, scoring at least three hits and causing extensive damage. Some of Leslie's bombers did not have bombs as they were accidentally released when the pilots attempted to use electrical arming switches. evertheless, Leslie and others still dove, strafing carrier decks and providing cover for those who had bombs. Gasoline ignited, creating an "inferno", while stacked bombs and ammunition detonated. VT-3 targeted Hiryū, which was hemmed in by Sōryū, Kaga, and Akagi, but achieved no hits. Within six minutes, Sōryū and Kaga were ablaze from stem to stern, as fires spread through the ships. Akagi, having been struck by only one bomb, took longer to burn, but the resulting fires quickly expanded and soon proved impossible to extinguish; she too was eventually consumed by flames and had to be abandoned. All three carriers remained temporarily afloat, as none had suffered damage below the waterline, other than the rudder damage to Akagi caused by the near miss close astern. Despite initial hopes that Akagi could be saved or at least towed back to Japan, all three carriers were eventually abandoned and scuttled. This experience would lead in a more modern firefighting system aboard newer Japanese carrier models and lead to upgrades on the older systems in their remaining carrier force as well. Half an hour later the next Japanese attack wave arrived at the American carrier Yorktown hitting it with their bombs and torpedoes. This attack set the Yorktown on fire and one torpedo also started to flood her at the same time. Within the next hour the flames would increase and doom the ship.

Late in the afternoon, a Saratoga scout aircraft located Hiryū, prompting Saratoga to launch a final strike of 24 dive bombers (including 6 SBDs from VS-6, 4 SBDs from VB-6, and 14 SBDs from Saratoga's VB-3). Despite Hiryū being defended by a strong cover of more than a dozen Zero fighters, the attack by orphaned Yorktown and orphaned Enterprise aircraft launched from Enterprise was successful: four bombs (possibly five) hit Hiryū, leaving her ablaze and unable to operate aircraft. Saratoga's second strike, launched late because of a communications error, concentrated on the remaining escort ships, but failed to score any hits. This second strike would also prevent further American close air support from starting, when surprisingly the second Japanese main attack run (started before their carriers were doomed) reached the Saratoga and damaged the ship greatly with it's bombs and torpedo.

After futile attempts at controlling the blaze, most of the crew remaining on Hiryū were evacuated and the remainder of the fleet continued sailing northeast in an attempt to intercept the remaining American carriers and fleet. Despite a scuttling attempt by a Japanese destroyer that hit her with a torpedo and then departed quickly, Hiryū stayed afloat for several more hours, being discovered early the next morning by an aircraft from the escort carrier Hosho and prompting hopes she could be saved, or at least towed back to Japan. Soon after being spotted, Hiryū sank. Rear-Admiral Tamon Yamaguchi, together with the ship's captain, Tomeo Kaku, chose to go down with the ship, costing Japan perhaps its best carrier officer.

As darkness fell, both sides took stock and made tentative plans for continuing the action. Admiral Fletcher, obliged to abandon the deadly damaged Yorktown and feeling he could not adequately command from a cruiser, ceded operational command to Spruance. Spruance believed the United States had won a Pyrrhic victory, but he was still unsure of what Japanese forces remained and was determined to safeguard Midway with his remaining forces. To aid his aviators, who had launched at extreme range, he had continued to close with Nagumo during the day and persisted as night fell. Finally, fearing a possible night encounter with Japanese surface forces, and rightfully believing Yamamoto still intended to invade, based in part on a contact report from the submarine Tamor Spruance changed course and withdrew to the east, turning back west towards the enemy at midnight. For his part, Yamamoto decided to continue the engagement and sent his remaining surface forces searching eastward for the American carriers. Simultaneously, he detached a cruiser raiding force to bombard the island and weaken the American defences there. The Japanese surface forces failed to make contact with the Americans because Spruance had decided to briefly withdraw eastward, and Yamamoto ordered a general assault on Midway, believing the American Fleet had retreaded to Hawaii after loosing it's carriers. This way Spruance come in contact with Yamamoto's heavy ships, including Yamato, in the dark and because of the Japanese Navy's superiority in night-attack tactics at the time, his forces quickly had been overwhelmed and sunk.

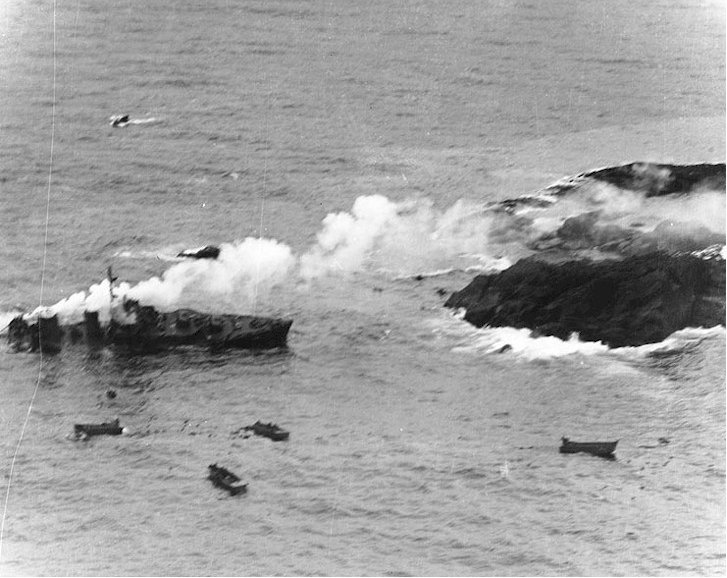

Totally defeated Spruance escaped westwards to Pearl Harbor, having no fleet remaining that could in any way stop the Japanese invasion of Midway. Yamamoto meanwhile hoped to find Spruance's remaining fleet and ordered part of his on 5 June, to extensive their searches eastwards of Midway, while his main fleet bombarded the island and covered the Japanese invasion. Towards the end of the day Yamamoto launched a search-and-destroy mission to seek out any remnants of Spruance force. This late afternoon strike narrowly missed detecting Spruance main body and failed to score hits on a straggling American destroyer. While bombarding the American positions since the night, the Japanese ships used their lights to aid the landings of Special Naval Landing Forces (SNLF) under heavy American fire. At the night of 5/6 June, the Japanese beachhead at Midway had been secured. When the sky brightened at 4:12 the Japanese started their main attack with the rising sun on the remaining American positions and fortifications on Midway.

By the time the battle ended, 5,422 Japanese had died. Casualties aboard the four carriers were: Akagi: 267; Kaga: 811; Hiryū: 392; Soryū: 711 (including Captain Yanagimoto, who chose to remain on board); a total of 2,181. The heavy cruisers Mikuma (sunk; 700 casualties) and Mogami (badly damaged; 92) accounted for another 792 deaths. In addition, the destroyers Arashio (bombed; 35) and Asashio (strafed by aircraft; 21) were both damaged during the air attacks which sank Mikuma and caused further damage to Mogami. Floatplanes were lost from the cruisers Chikuma (3) and Tone (2). Dead aboard the destroyers Tanikaze (11), Arashi (1), Kazagumo (1) and the fleet oiler Akebono Maru (10) made up 23 casualties. The remaining 2,365 dead Japanese were these that landed on the island with many dying from initial American fire during the landing. Some even were killed by the Japanese own bombardment of remaining American defence positions. At the end of the battle, the U.S. lost the all of their carriers, 4 heavy cruisers, 9 destroyers and 387 aircraft (many of them land-based that were destroyed during the bombardment, or captured by the Japanese when Midway fell into their hands). The 3,156 American defenders of Midway lost the beach when the initial 1,500 Japanese invading forces were soon supported by their fleet bombardment of American positions and reinforcements coming from the landing-boats. While 2,743 Americans died until 8 June, the fighting on Midway would continue until 10 June. Until then the last American resistance was destroyed and 5,000 Japanese soldiers including a engineer battalion left to guard Midway for a future assault on Hawaii from here.

On 10 June, the Imperial Japanese Navy conveyed to the military liaison conference an incomplete picture of the results of the battle. Chūichi Nagumo's detailed battle report was submitted to the high command on 15 June. It was intended only for the highest echelons in the Japanese Navy and government, and was guarded closely throughout the war. In it, one of the more striking revelations is the comment on the Mobile Force Commander's (Nagumo's) estimates: "The enemy is not aware of our plans (we were not discovered until early in the morning of the 5th at the earliest)." In reality, the whole operation had been compromised from the beginning by Allied code-breaking efforts. The Japanese public and much of the military command structure were kept in the dark about the extent of the defeat: Japanese news announced a great victory with the destruction of the American carriers and the conquest of Midway. Only Emperor Hirohito and the highest Navy command personnel were accurately informed of the carrier and pilot losses. Consequently, even the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) continued to believe, for at least a short time, that the fleet was still in good condition. On the return of the Japanese fleet to Hashirajima on 14 June the wounded were immediately transferred to naval hospitals; most were classified as "secret patients", placed in isolation wards and quarantined from other patients and their own families to keep this major defeat secret. The remaining officers and men were quickly dispersed to other units of the fleet and, without being allowed to see family or friends, were shipped to units in the South Pacific, where the majority died in battle. None of the flag officers or staff of the Combined Fleet were penalized, with Nagumo later being placed in command of the rebuilt carrier force.

As a result of the defeat, new procedures were adopted whereby more Japanese aircraft were refueled and re-armed on the flight deck, rather than in the hangars, and the practice of draining all unused fuel lines was adopted. The new carriers being built were redesigned to incorporate only two flight deck elevators and new firefighting equipment. More carrier crew members were trained in damage-control and firefighting techniques, although the losses later in the war suggest that there were still problems in this area. Replacement pilots were pushed through an abbreviated training regimen in order to meet the short-term needs of the fleet. This led to a sharp decline in the quality of the aviators produced. These inexperienced pilots were fed into front-line units, while the veterans who remained after Midway and the Solomons campaign were forced to share an increased workload as conditions grew more desperate, with few being given a chance to rest in rear areas or in the home islands. As a result, Japanese naval air groups as a whole progressively deteriorated during the war while their American adversaries continued to improve. This continued until 1943/44, when the IJA and IJN combined their pilot training and aerial missions under Shogun Tojo to increas their fighting power and precision to stop the Allied advance against the Co-Prosperity Sphere.

Three U.S. airmen, Ensign Wesley Osmus, a pilot from Yorktown; Ensign Frank O'Flaherty, a pilot from Enterprise; and Aviation Machinist's Mate Bruno F. (or P.) Gaido, the radioman-gunner of O'Flaherty's SBD, were captured by the Japanese during the battle. Osmus was held on Arashi; O'Flaherty and Gaido on the cruiser Nagara, all three were interrogated, and then killed by being tied to water-filled kerosene cans and thrown overboard to drown. The report filed by Nagumo tersely states of Ensign Osmus, "He died on 6 June and was buried at sea"; O'Flaherty and Gaido's fates were not mentioned in Nagumo's report. The execution of Ensign Wesley Osmus in this manner was apparently ordered by Arashi's captain, Watanabe Yasumasa. Two enlisted men from Mikuma were rescued from a life raft on 9 June by the Japanese Fleet and brought to Midway. Another 35 crewmen from Hiryū were taken from a lifeboat by some Japanese scout ship late on 19 June , they were brought to Midway too.

The Battle of Midway has often been called "the turning point of the Pacific". It was a Pyrrhic Victory for both sides as the Japanese had lost their carriers, while the Allies had lost the American Carriers and Midway. This meant that the USS Wasp was now the only American carrier in the Pacific, with no new ones being completed before the end of 1942 (the new Essex-class fleet carriers). Unlike Japan, the Co-Prosperity Sphere and Yamamoto had hoped, this major loss did not bring the United States to the negotiation table, so the Japanese Empire revived Operation FS to invade and occupy, the Salomones, Fiji and Samoa; attacked Australia, Alaska, and Ceylon; and even attempted to conquer Hawaii. The loss of four large fleet carriers and over 40% of the carriers' highly trained aircraft mechanics and technicians, plus the essential flight-deck crews and armorers, and the loss of organizational knowledge embodied in such highly trained crews, was a heavy blow to the Japanese carrier fleet. The Japanese carrier losses lead them to abandon their battleships and restart their carrier building program, that had been halted to use the resources for new transport ships and escorts because of their recent losses.

The before superior Japanese carrier force had received a first heavy blow and in the time it took Japan to build three carriers, the U.S. Navy commissioned more than two dozen fleet and light fleet carriers, and numerous escort carriers, industrially outmatching their enemy on the long run. By 1942 the United States was already three years into a shipbuilding program mandated by the Second Vinson Act, intended to make the navy larger than all the Axis Central Powers and Co-Prosperperity Sphere navies combined, plus the British and French navies, which it was feared might fall into Axis Central Powers hands. Both the United States and Japan accelerated the training of aircrew, but the United States by then had a more effective pilot rotation system, which meant that more veterans survived and went on to training or command billets, where they were able to pass on lessons they had learned in training, instead of remaining in combat, where errors were more likely to be fatal. To make up for their losses, the Japanese now split their Carrier Fleets in half, with only one Carrier in each fleet until the new ones would replace the lost ones. This way their carrier fleets were suddenly half as strong as before, seriously weekending their overall defence and attack capabilities.

![andean-states-w-ecuadorianperuvian-war-guerra-del-41-border-changes-1944-map-[2]-358420-p.jpg](https://www.antiquemapsandprints.com/ekmps/shops/richben90/images/andean-states-w-ecuadorianperuvian-war-guerra-del-41-border-changes-1944-map-[2]-358420-p.jpg)