The Best Laid Plans

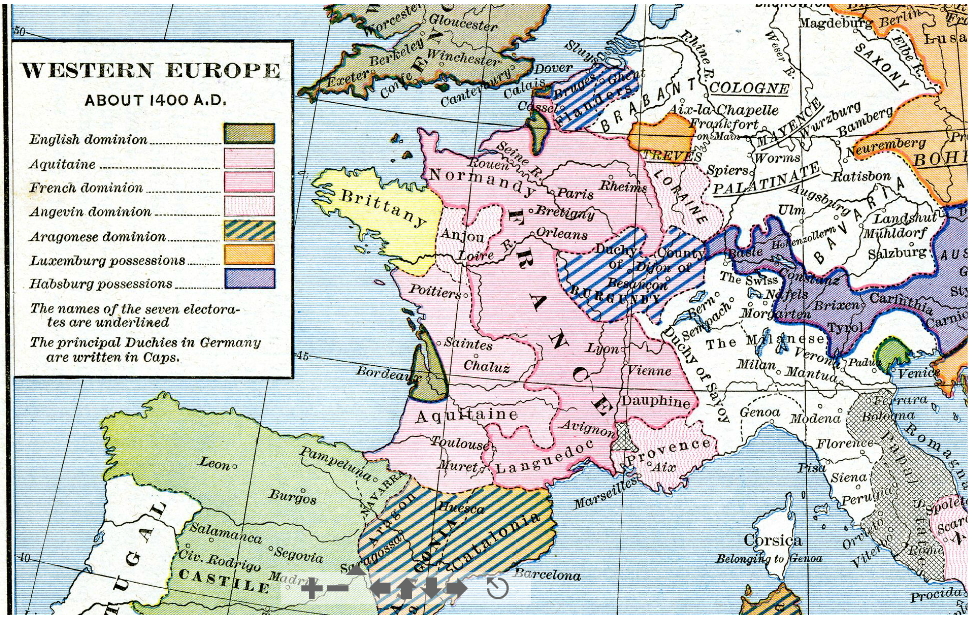

Europe and its environs at the death of Gian Maria in late 1433

Gian Maria's death left his vast estates in the hands of his son Gian Galeazzo II, promptly acclaimed and coronated "king of Sardinia, Corsica, Valencia, Mallorca, Sicily and Grand Duke of Lombardy, Italy, and Provence" in the duomo of Milan on June 9th 1433. The regency- and control over the kingdom- hinged on who held the the person of the two year old monarch. Two factions vied for dominance- the Savoyards, under the Dowager Queen Giovanna of Savoy and her father Duke Amadeus VIII of Savoy (since his cousin's death in 1418 the ruler of Turin and Piedmont as well), and the Sicilians, under King Filippo Maria of Naples. Duke Amadeus retired and abdicated the government of his territories to his son and heir Ludovico.

Filippo Maria was in Palermo when news of his brother's murder filtered north. Crucially his position gave him a few days' warning over the Savoy, and he immediately rushed to Lombardy with whatever men he had on hand. Gian Maria's campaigns had made the prospect of his violent demise an eminent possibility, and Filippo himself had many friends in the north, greatest of whom was

Cosimo de Medici, head of the powerful Medici family of Florence and in 1433 the forty four year old chair of the Bank of St Ambrose. Cosimo's son Piero, now sixteen, had married Filippo Maria's bastard daughter Valentina in 1429, as her father made his preparations for the Crusade. Cosimo came to respect the calm and clever Filippo, whose frugal and pragmatic tenure easily established a working relationship between him and the merchant classes similar to that of his father Gian Galeazzo. Filippo's heavy involvement in Milanese politics, the careful encroachment of Sicilian partisans and Florentine coin in the Lombard capital, and the surprisingly rapid ascension of Sicilian power in the north have led some to suggest that the two were in 1433 scheming to assassinate Gian Maria and seize the regency for Gian Galeazzo II for themselves, but neither were foolish enough to leave any incriminating evidence behind for posterity and Gian Maria's murder scuppered any possible plans.

Opposing Filippo Maria in support of the Dowager Queen were “The Signore Diadochi” the great captains of Gian Maria: the Malatesta, the Terzi, the Rossi, and new names, new men who distinguished themselves and caught Gian Maria's eye. Perhaps the most famous of these was the Crusader Albert of Chur, a Swiss commander who was knighted by the king after Lodi and commanded the foot at the battle of Karitza. Albert had risen quickly under Gian Maria's favor, and shared his king's opinion of his brother- that he was a cowardly snake, if a useful one. More significantly Albert feared- like the rest of the captains- that the famously frugal and un-warlike Filippo would end the largesse they enjoyed under Gian Maria, and viewed the long regency as a means of becoming de facto rulers of Lombardy.

Gian Maria's death in Carthage provided a decisive advantage for Filippo- the captains and the bulk of their supporters were with the late king in Africa, and Filippo Maria controlled the seas. The new regent delayed retrieving the stranded Black Legion for nearly a year, protesting that the Legion was needed to secure Africa in the face of a Hafsid reconquest, and in the meantime seized the capital with his followers. Giovanna herself absconded to Savoy with the young king and as much of the treasury as she could carry, although in truth there was not much to take. Gian Maria's warmongering had left his finances in perilous condition, even as state revenues were greater than ever. Filippo himself could not trust the Black Legion but neither was he immediately willing to destroy them- calling the Legion “the only good idea my brother ever had”- and so long as he could secure the treasury there would be men among them who could overcome their disdain for the Sicilian serpent.

In Italy Filippo Maria sold Belluno and Vicenza to the Republic of Venice, in order to pay off his brother's debts and recoup the gold stolen by the Savoy. Both territories were rather peripheral to Italian interests, and by strengthening Venice Filippo Maria hoped additionally to create a useful buffer against Austria. The cash was then put to use employing a new Swiss company. The Lord Regent then reached out to the condotierri Enrico Malatesta in Africa, offering him his daughter Anna Maria and full command of the Legion in exchange for betraying his comrades. As the legions crossed the Mediterranean Albert and his fellows were fallen upon by the Malatesta and cast overboard. Upon arriving in Italy, however, Filippo promptly betrayed Enrico and had him hanged as a traitor. He then installed his own Sicilian and Albanian officers in the echelons of the Legion, and gave total command to his own condotierri- chief among them Francesco Brussoni, a veteran of Lodi and the Great Turkish War- and divided it into two groups- one cohort to garrison Innsbruck, another to garrison Carthage, both far removed from Milan and its politics. Filippo's own mercenaries- far less attached to Gian Maria and his son- then marched into Savoy, annexing the county entirely and retrieving the wayward king and his mother. One might have expected the prince to meet with an unfortunate accident- this was the fear that motivated Giovanna to flight- but it must be remembered that Gian Galeazzo II was not only Filippo Maria's nephew but also his heir, for in 1433 he had no legitimate sons of his body. Consequently the two year old was quickly betrothed to his first cousin Valentina, Filippo's youngest daughter, and formally acknowledged as the heir to the united Visconti dominions. The loss of so many skilled officers may have secured Italy but it also meant the loss of valuable leadership experience and Italy would suffer for it soon enough.

Gian Maria was not the only significant death of 1433. As King Filippo Maria was consolidating his grip on Lombardy, Duke Philip I of Brabant breathed his last in Antwerp at the relatively young age of forty-seven. With his death died the Brabantian branch of the House of Valois-Burgundy, and the unstable peace in the Low Countries. Duke Henry's only son Philip died from a hunting accident at age fourteen, leaving the duchy to pass to his sister, the Duchess Margaret I of Brabant, currently betrothed to Duke Henry of Holland and Hainaut. By the marriage treaty forced upon them by King Henry V of England, if Duke Philip died without legitimate male heirs then Brabant would pass to Margaret, thus unifying Holland, Hainaut and Brabant under the younger house of Lancaster.

Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy

The succession was immediately contested by Duke Philip of Burgundy, also Count of Flanders, who invaded Brabant in order press his claim. Duke Philip was supported by his royal cousin King Louis XI of France, just as Duke Humphry sought the aid of his oldest brother, King Henry V of England. Fifteen years after the Peace of Poitiers England and France were once again at war.

Henry dispatched his brother Thomas, the duke of Clarence, to Calais with an English army. By the Treaty of Poitiers English Picardy had been enlarged nearly thirty miles inland, and from this heavily fortified position Henry intended to conquer all of Picardy. If this could be accomplished then Flanders would be isolated from France and quickly overrun; at a single stroke Henry might secure all of the Low Countries for the House of Lancaster.

Louis marched from Paris and met the English at Arras on June 19th, 1433, presently under siege. Thomas was confident of his success. His army was larger, his commanders veterans from Henry's wars a decade prior, and the French had proven time and again to be their own worst enemy. As the last morning mists burned away Prince Thomas was treated to an unsettlingly novel sight- the French army deployed, not in columns or in lines but in great ungainly blocks, a “veritable forest of pikes” checkered like squares on a chessboard. Louis' army contained many Hussite officers on lease from his Polish ally King Frederick as well as a smattering of Swiss, French and German officers from the Crusades, and Louis himself had integrated lessons of both armies and drilled the French soldiers relentlessly in the fields outside Paris. Jan Sizka had proved the power of the gun, Gian Maria had shown the strength of the pike, and Louis now combined them both in the first organized deployment of pike and shot on the continent.

Thomas ignored his misgivings and ordered his men to battle, trusting his fabled longbowmen to overwhelm the massed French foot and his siege lines to repel them if they did. The French, however, largely shrugged off the English barrage and advanced with the inexorable force of a tidal wave. Louis' artillery opened a hole in the English defenses and by the end of the day Thomas and the majority of his army were dead.

Arras proved a major upset to foreign monarchs, most of whom expected another English victory and naturally were quite shocked that the French should have the gall to win for once. The Duchess Jacqueline fainted on hearing of her brother-in-law's demise, while King Frederick of Poland remarked dryly that “while the English king had an army, the French army had a king.”

Louis swiftly followed up his victory by besieging Calais on June 22nd and after seizing Hainaut in July a combined Franco-Burgundian army drove Duke Humphrey from Brabant. The advance faltered in Holland, as the Dutch broke their levies and flooded the countryside, effectively rendering their cities islands. Louis thus turned south, advancing quickly into Aquitaine. The French defeated an Anglo-Breton army south of Angers and after a grueling four month siege Louis triumphantly entered into Poitiers on October 4th 1433. By the end of the year it seemed as if Louis might effect a complete reconquest of the south.

Louis XI's triumphal entry into Poitiers

It was at this point that Emperor Albert the Magnanimous chose to intervene. Like the Luxemburgs before him Albert of Austria decided to intercede personally between his two powerful neighbors. Albert himself had no marriage ties to the Lancaster kings of England, but he viewed the English as a valuable counterweight to Italian power in the west and an obstacle to further French encroachments on the Rhineland, and feared for the stability of the Imperial frontier should England be driven from the continent as Louis seemed about to accomplish.

By the Treaty of Poitiers, Henry V of England and his ally Duke Humphrey were forced to acknowledge Duke Philip of Burgundy as the ruler of Brabant, forever renouncing any claim over the duchy and cede the county of Hainaut to Brabant as well. England was also required to cede both Poitiers and Auvergne to France as the price of peace, and additionally pay a significant ransom for English prisoners taken by Louis on his campaign.

Louis' conquests ensured that the French would forever remember Louis' reign as a period of national exultation. The conquest of Poitiers, coming so soon after Gian Maria's death and the English defeat at Arras, seemed all at once to expunge the shameful debacle of two decades before. “Poitiers was humiliation, defeat, degradation at the hands of

les Anglois and

les Italiennes,” a French diplomat explained to his Austrian counterpart, “In 1433 both were destroyed by the efforts of God and King; now Poitiers was victory, glory, triumph over our assailants and the recovery of the honor and dignity of France.” King Louis himself had a different perspective- the king had won a great victory, but complained that it was not as decisive as it should have been, and he excoriated Albert in his journal. “The Germans have robbed me of my triumph,” he railed bitterly, “all the South lay before me, and now forever out of my reach!” Further disappointment over failed ambitions followed when Philip of Burgundy ceded Burgundy to Louis and took up permanent residence at Antwerp. For his support Louis had demanded Philip cede either Burgundy or Flanders to the king as both were French fiefs, undoubtedly hoping that Philip would chose his ancestral lands over Flanders itself. Philip, however, proved his far-sightedness when he chose instead to consolidate his hold on the Low Countries. Louis attempted to force the issue by occupying the Free County of Burgundy but Emperor Albert again interceded to thwart him, this time at Philip's personal request.

The Battle of Arras eliminated any lingering doubts that “the Italian model” was the future of warfare. Already king Frederick of Poland had organized his regiments in the French style, utilizing the veterans of the Hussite Wars- including the venerable Jan Zizka, now nearly seventy- and French observers from Louis' army. France and Poland drew ever closer by the friendship of their kings and the cooperation of their officers, and Frederick sealed his newfound alliance by marrying Louis' daughter the Princess Margaret of Nevers in 1433. Frederick proved a capable and energetic ruler, and although he could not curb the powerful Lithuanian and Polish nobility (outside of Prussia, Poznan and Krakow, where he used settlers from Brandenburg to establish a contingent of royal knights to undergird his regime) and did not waste effort in trying to do so. Instead he cleverly exploited the Hussite conflicts to strip most of the local magnates of their lands and turn Bohemia into a stronghold for royal power, centering his regime on the wealthy city of Legnica in Silesia, which soon became the de facto capital of Hohenzollern Poland.

England too learned from Arras, and Henry devoted the rest of the decade to establishing a “Louisan Army” from the aging veterans and yeomen retainers of his army; the next French invasion of Aquitaine would meet with much stiffer resistance.

Of all the great powers only Austria failed to reform her military. This was not for lack of trying- Albert was no fool and he clearly saw the danger in being bracketed by Italy on the one hand and Poland on the other. Yet Hungary, although far from poor, was a thoroughly rural nation, given over to the rule of powerful landed magnates, all of whom jealously guarded their privileges, and the Habsburgs' estates in Austria suffered greatly from Gian Maria's conquests, as Tirol especially (but also Further Austria, including the Breisgau in southern Alsace) were easily among the most valuable Habsburg lands and their loss crippled the Emperor's finances. Although Albert- a fairly capable and august ruler, and additionally a successful Crusader after 1430- was popular, his gains in Serbia could not convince the Magyar nobles to surrender their much cherished rights. His costly failures in Germany further weakened his position, and when in 1433 he was presented with an ultimatum he had no choice but to abandon the project. By the Golden Charter of 1433 Albert effectively alienated the royal power of taxation and reaffirmed the rights of the Hungarians to maintain and raise their soldiers at the behest of the king. By legend, Albert, upon signing the charter, allegedly remarked that “it was the death warrant of Hungary and the doom of your dynasties.” Albert himself died not long after the charter was signed, passing into the embrace of God on March 3rd 1434.

For nearly a century Hungary had been united with either Austria, Bohemia or both under first the House of Luxembourg and then the House of Habsburg. During this time most of the Hungarian kings had treated the kingdom as merely a tool to advance their interests within the empire, and by 1435 there was significant unrest among the aristocracy and open talk of avoiding any further imperial entanglements. In the face of these and other dangers the twenty year old Duke Frederick V of Austria could rely upon only himself, and he soon proved readily equal to the challenge.

Frederick V of Austria, King of Hungary and claimant to the Holy Roman Empire

Mocked as “king sleepy head” during his lifetime, Frederick V is widely considered the House of Habsburg's greatest prince and diplomat, and even at such a young age he worked tirelessly to secure his rightful inheritance. Frederick V consciously chose to pursue the Hungarian crown before the German and Imperial inheritance; this may have been a simple matter of expedience as much as anything else- Frederick was in Hungary, and not Germany, when his uncle died; but Frederick, who even at such a young age demonstrated great aptitude as a statesman, understood that he would appear more dignified to first assemble the Hungarians and secure his election, and only then enter Germany, on his own terms and with his uncle's crown already secured, rather than rushing first to Germany and then hastily returning hat in hand back to Hungary. This was a wise choice, but it also meant that Frederick could not personally attend to Germany for the first few months following Albert's death, on opportunity Filippo Maria- himself equal to Frederick's genius and having two decades of experience on the prodigal Austrian king- readily and eagerly exploited.

As the silver-tongued serpent schemed, Frederick of Austria won the truculent Hungarian nobility to his cause. Appealing to the assembled nobles in person, he pledged- in fluent Hungarian- to uphold their rights, respect their laws and customs, and vowed upon the Bible to hold his court in Hungary “until such time that I have an heir of my body, who might in his manhood come among you as your king.” Taking in addition the sister of the Transylvanian magnate Janos Hunyadi as his wife Frederick masterfully assuaged the misgivings of the Hungarians and secured his near-unanimous election to the Hungarian throne. Crucially among the concessions granted to the Hungarians was a pledge that he would abandon the “tyrannical pretensions” of Albert and uphold their “Golden Liberties” as set forth in the Charter of 1433.

In the meantime Filippo Maria acted with full alacrity to pursue his election. He first sought the Prince Bishoprics, donating an immense wealth to the Archbishop of Cologne, ostensibly to complete the cathedral of Cologne but in actuality a bribe. He argued that the young king Frederick clearly viewed his own dynastic interests as superior to the empire and was lacking in experience to Filippo Maria, a veteran Crusader; the archbishop, in truth, had a longstanding relationship with the Visconti as the Arch-Chancellor of Italy and Filippo had been courting him for nearly a decade by 1434. Thus securing his first vote he turned to Trier, but the archbishop resented the Visconti alienating Provence from the Empire- and thus from himself- and rebuffed Gian Maria's advances. The Archbishop of Trier proved more amenable but he eventually revealed that he had already “sworn a solemn oath to Emperor Albert” to support the Habsburgs, and Filippo, dismayed, praised the archbishop's integrity and wrote him off as a lost cause. Amidst this furious War of Letters Filippo Maria approached Humphrey of Holland and between them they concocted a plan to “make the duke a king and the king an emperor.”

In June Filippo married his third daughter Violante to Louis IV, heir general to his father Louis III, the Count Palatine of the Rhine- one of the seven Prince Electors of the Empire. He gave his eldest daughter Caterina to another Wittelsbach heir in July, pledging her to Louis IX, future duke of Bavaria-Landshut and son of the current Duke Henry XVI. Filippo himself took the fourteen year old Elisabeth Louis' sister, as his second wife following Sofia's death in August, thus not only reconciling the powerful Bavaria-Landshut family from their lingering ties to Barnabo Visconti[1] but also binding himself thrice over to the prestigious and powerful Wittlesbachs, archrivals of the Austrian Habsburgs and one of the three great dynasties of Germany. As dowry Duke Henry XVI received the Principality of Achaia. The German prince had no interest in Greece, but a princely title- which being a papal fief and well removed from Germany might readily become a royal crown in due time- was another matter entirely. The exceptionally ambitious Henry did not stop here- the duke married his eldest daughter Joanna to the Dauphin (and future king) Charles of France in 1429. King Louis XI of France encouraged the royal pretensions of Bavaria, seeing in the Wittlesbachs a powerful ally with which to aggravate both Austria and Italy. As Albert of Austria proved in 1432 an undivided Empire could easily stymie French ambitions on the continent; Bavaria was well positioned to counter any further such intercessions from deep within Germany itself.

Frederick had by now secured the Hungarian throne, and subsequently sought to reclaim the rest of the Luxembourg inheritance by gaining not only the Empire but Bohemia as well; surely, the Austrian archduke naively believed, Frederick of Brandenburg-Poland could not seek to keep Bohemia and Brandenburg both, as Frederick II was presently the heir to Brandenburg in addition to the King of Bohemia-Poland-Lithuania and had no eligible siblings. Frederick himself was his father Margrave Frederick I's second son, but his elder brother John the Alchemist, had willingly absconded to Bayreuth at the behest of their father, where he spent his days turning the mines of that province towards his efforts to extract gold from lead.[A]

Consequently Frederick V offered to Elector Frederick II of Brandenburg his sister Elizabeth of Austria and his renunciation of the disputed provinces of Silesia and Lusatia to Brandenburg-Poland, in exchange for Bohemia and its electoral vote for the House of Habsburg. The Saxon Elector Duke Frederick II was since 1431 already married to Frederick V's sister Margaret, winning that vote for the Habsburgs as well.

This was Filippo Maria's nightmare: the powerful kingdoms of Hungary and Poland, bound by blood to the three electorates of Brandenburg, Saxony, and Bohemia and thus coming only a single vote from winning the Habsburgs the Imperial crown. Yet Frederick “The Iron Tooth” of Poland-Lithuania had no intention of ceding his rightful inheritance, certainly not to this young Austrian upstart. He accepted the Habsburg bride but not the alliance, and upon entering Berlin he claimed his birthright as King Frederick I of Bohemia, Poland and Lithuania and the Prince Elector of Brandenburg itself.

Frederick's coronation immediately and dramatically arrested all of the scheming and diplomatic maneuvering between the competing imperial candidates. “The chimeric monstrosity of a full union between Jogaila and Hohenzollern,” wrote Filippo in his memoirs, “represented an unqualified evil to which all of Europe was strenuously opposed. In such an overmighty prince rested a mortal threat to the peace of the Empire, and the complete and everlasting destruction of the delicate balance of power between the great nations of Europe.” Filippo's undoubtedly biased account is one of the first explicit references to the balance of power theory as a guiding international principle, and once formulated it became the basis for European diplomacy for the whole of the Early Modern period.

That Filippo Maria Visconti, whose father and brother had shamelessly expanded their state through any and all means fair or foul, should now decry Frederick I as a menace to the general peace was an irony not lost on the Polish king, who bitterly denounced the Serpents of Milan, professing that “I have never borne arms against my fellow Christians, as have the Visconti against the Habsburgs, the Trastamara and the Valois.” Yet Filippo Maria had instinctively articulated the fears of the German electors and positioned himself as the champion of their cause. Despite protestations that he was merely claiming his father's inheritance, Frederick of Poland, by insisting on this “chimera” sought to control not one but two electorates in personal union, an unprecedented concentration of power within the empire. Filippo Maria understood in Frederick a mortal threat to Italian hegemony, for if Frederick should be unopposed his state would in time naturally eclipse not only the Austrians but the Lombards as well.

At the Imperial council of Constanz on January 19th 1435 the Germans demanded Frederick immediately vacate Brandenburg. Frederick responded by offering to reinstate his brother John, but as the elder Hohenzollern had already been disinherited because of his complete disinterest in governance this amounted to Frederick retaining de facto control of all his territories and was rejected out of hand. When Frederick failed to recant the Council formally denounced him as a warmonger and traitor, and his electorates were declared null and void.

King Filippo Maria offered to support Frederick of Austria's cause in Bohemia if in exchange his nephew would be formally invested as King of Burgundy and an eighth Prince-elector. This was technically against the empire's legal precedence, as by traditional feudal custom kings could be either elevated from below by their vassals' acclamation of anointed from above by either the Emperor or the Pope. The Burgundian crown was a peer, not an overlord, of the Electors, and despite the papal legate approving of the deal “for the sake of the general peace” the electors were effectively stealing the Emperor's scepter to use towards their own designs. Yet with no Emperor in Germany, two electorates in revolt and both Filippo Maria and Frederick of Austria insisting, for their own reasons[2], on the deal and the subsequent campaign against Poland as necessary prerequisites to any possible election the College viewed the agreement as a preliminary contract to be legitimized by official investiture following the war.

No sooner was the Visconti proposal accepted than Duke Humphrey of Holland rose to make his own suggestion. The duke remarked that with the newly minted eighth electorate, the Empire now faced the prospect of a tied electoral college, and yet had only six electors present at the council itself. He therefore argued that “as the Electoral dignity should be reserved for only a select few” the precedent set by the new King of Burgundy was that “the royal dignity and the electoral dignity are conjoined; to gain one automatically implies the other” and reminded the Germans that he himself- in addition to being a prince of England- owned essentially all of the old kingdom of Frisia, a throne left in abeyance since its conquest by the Franks under Charlemagne. The princes proved amenable to the Dutch proposal (not least since they now twice established the precedent that both a royal crown and electoral vote could be created by their own wishes in the absence of a sitting emperor) and correspondingly Duke Humphrey of Holland became King Humphrey I of Frisia, the ninth Elector of the Holy Roman Empire, and took his place alongside the Habsburgs and Visconti on the bench. Filippo Maria remained silent during the Frisian vote, raising his voice in support only once he saw the measure was likely to pass. The day after King Humphrey's formal investiture at the hands of the Electoral College Filippo Maria announced the double betrothal of his daughters to King Humphrey's son Henry and Duke Charles of Lorraine. It was a shrewd maneuver- securing not only the newly minted electoral vote for himself but also two marriage alliances with powerful princes in the Rhenish territories, as well as indirect links to both France and England via younger branches of their royal dynasties. Frederick V “only now realized the noose which the Silver-tongued serpent had so readily woven around the neck of his imperial ambitions,” but with the two electorates already acclaimed and accepted into the College there was little he could do but seethe at the “votes conjured from air to counter the two gained by my right and the Hohenzollern Rebellion.”

The ensuing war- known to history as the War of the Bohemian Succession- proved a major turning point in Europe, and neither Frederick of Austria, nor Frederick of Poland, nor Filippo Maria would expect the result.

[1]Barnabo Visconti, it should be remembered, was Gian Galeazzo's cruel uncle and predecessor as ruler of Milan, whom the latter usurped and poisoned; Barnabo's daughter Maddalena Visconti married duke Henry's father Frederick and Henry was her son, thus making Filippo Maria and Henry second cousins and necessitating a Papal dispensation for the match

[2]Frederick later revealed that, absent the two electoral votes of Bohemia and Brandenburg (both of which he desired to strip from the Hohenzollerns, respectively to keep for himself and to grant some as yet undetermined ally or supporter, just as the Luxembourgs had done prior to the Golden Bull nearly eight decades before) he felt insecure in pressing his candidacy; as the Visconti including Burgundy had at least two votes already this was perhaps a prudent decision, though the Frisian marriage the following day revealed to him the trap laid by the Visconti

[A]This is as OTL. No, really, read the Wiki page for yourself. We very nearly had a Brandenburg-Poland-Lithuania-(Prussia) union in OTL because Frederick's brother John the Alchemist was an uber-nerd who would rather play around with alchemy than become one of the seven most powerful people in Germany. I love history sometimes. Also, reading the page just now I realized I could have added Saxony to the family since Ladislaus died and the Hohenzollerns got Poland to back them up...