Yikes. I do not see even the Catholic Electors standing idle while Charles chops off the head of one of their own. And Sweden is already moving into North Germany. We could have quite the situation on our hands.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Thriving Pomegranate Seeds: A Trastámara Spain Timeline

- Thread starter Awkwardvulture

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 77 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

1548 1548 Portraits for: Prince Eric Duke of Kalmar, Anna of Mecklenburg, William Duke of Cleves, and Wilhemina of Bavaria 1549 1550 to 1555 Images I for 1550 to 1555 1555 Map of North America with Colonies 1555 Family Trees Epilogue, and 2020 Map of North AmericaWell, most of the Protestant Princes are displeased, and some of the Catholic ones are as well, but a show of force may discourage some of them from rebelling... you are correct though, as things may eventually heat up again...Yikes. I do not see even the Catholic Electors standing idle while Charles chops off the head of one of their own. And Sweden is already moving into North Germany. We could have quite the situation on our hands.

More than displeased. Historically most of the Catholic Princes didn't assist the Emperor in quelling the league. Furthermore much of Germany was outraged at the mere imprisonment of several electors. Now one of them has been executed. And the Hapsburgs do not possess Bohemia and Hungary (you could maybe add some mention of the Emperor's brother in law lending him some support. What's more the Hapsburg lands are being split, with states carved out for Archdukes Maximilian and Ferdinand. So not only are the Hapsburgs "bloody minded tyrants", as the electors will now see them, they lack the military and economic power they had in IRL.

I fully expect that it will be difficult if not impossible to have Prince Philip be crowned Emperor. Perhaps the Electors would settle on another Catholic Prince, like the Duke of Bavaria, or even one of Charles's brothers, IRL Ferdinand was pretty chill with the Protestants.

IRL France used this opportunity to foment dissent in the HRE and attack the Emperor. Here they might instead offer Charles a deal. France will help him secure his intrests in the Empire, but only if Charles drops his alignment with Spain and allies with France.

I fully expect that it will be difficult if not impossible to have Prince Philip be crowned Emperor. Perhaps the Electors would settle on another Catholic Prince, like the Duke of Bavaria, or even one of Charles's brothers, IRL Ferdinand was pretty chill with the Protestants.

IRL France used this opportunity to foment dissent in the HRE and attack the Emperor. Here they might instead offer Charles a deal. France will help him secure his intrests in the Empire, but only if Charles drops his alignment with Spain and allies with France.

True, conflict will soon come and we'll have to see how it all unfolds...More than displeased. Historically most of the Catholic Princes didn't assist the Emperor in quelling the league. Furthermore much of Germany was outraged at the mere imprisonment of several electors. Now one of them has been executed. And the Hapsburgs do not possess Bohemia and Hungary (you could maybe add some mention of the Emperor's brother in law lending him some support. What's more the Hapsburg lands are being split, with states carved out for Archdukes Maximilian and Ferdinand. So not only are the Hapsburgs "bloody minded tyrants", as the electors will now see them, they lack the military and economic power they had in IRL.

I fully expect that it will be difficult if not impossible to have Prince Philip be crowned Emperor. Perhaps the Electors would settle on another Catholic Prince, like the Duke of Bavaria, or even one of Charles's brothers, IRL Ferdinand was pretty chill with the Protestants.

IRL France used this opportunity to foment dissent in the HRE and attack the Emperor. Here they might instead offer Charles a deal. France will help him secure his intrests in the Empire, but only if Charles drops his alignment with Spain and allies with France.

Thank you, I may PM you about it soon...If you need any help in planing it you are more than welcome to ask.

1549

In Spain, at the Alcázar of the Toledo, on the first of December, Margaret of Austria, Queen Mother of Spain died of a fever from her infected and abscessed leg, at the age of sixty-nine. Margaret, though in debilitating pain, had made her will and testament clear in her characteristic diligence. Of particular note is that she left some of the jewels from her wedding (including a sapphire necklace) to her beloved Juan III to her eldest child, the Infanta Isabella, Dowager Duchess of Milan. These jewels would never be worn by the Dowager Duchess, for unbeknownst to Margaret, her daughter had died of breast cancer, over two weeks prior… Whether the news merely arrived too slowly or was purposefully kept from her by the King is unknown, but the latter is most likely, for several days later, her son Ferdinand VI had wrote that,”The death of my mother, the Dowager Queen, greatly saddens me, but I am grateful that she was not informed of my sister’s death, so she passed at ease with herself.” The chief mourner at Margaret of Austria’s funeral, unsurprisingly, was her granddaughter-in-law, Catherine de Medici, for Margaret was the closest thing that Catherine ever had to a mother, having been orphaned in infancy. The Dowager Queen Margaret (Margarita in Spanish) would later be interned in Granada, Royal Chapel of Granada finally rejoining her late husband Juan III of Spain after over twenty-five years of widowhood.

To the west, in the Kingdom of Portugal at the Ribeira Palace Manuel, Prince of Portugal had his second child, with his wife. On December 19th, barely eleven months after giving birth to her first child, the sixteen-year-old Catherine of England, Princess of England gave birth to another son, named Manuel for his father. The birth of a second son, in such rapid succession, was seen as a good omen for the marriage, for even if the Prince of Portugal was still unfaithful to his wife, Catherine of England had proven herself to rather be capable in birthing children. The younger Manuel’s godparents would include three of his grandfather’s siblings, as well as his eldest aunt. Specifically, they were the Infante Afonso, Duke of Beja, the Infanta Beatrice (Beatriz in Portuguese), Duchess of Braganza, and his youngest grand-uncle, Infante Ferdinand, the Duke of Guarda and the Infanta Eleanor, Suo Jure Duchess of Barcleos. The Dowager Princess of Asturias, who had resolved to never remarry (though there were rumors that one of her guardsmen was her lover), had designated her second nephew as her heir to her duchy in her will, and would go on to be exceptionally close with the boy, almost as if she were another mother to him.

To then north, in France there were some vital happenings for the House of Valois, particularly its cadet branches in Orleans and Anjou. Firstly, at the Château d'Amboise Prince Charles, the Duc d’Orleans and Maria, the Duchesse of Savoy would, after ten years of marriage, finally have a child that would live past infancy. Unfortunately, the child, born on February 4th, was not quite the gender that her parents had hoped for, yet little Claude would be well cared for by her parents, and would provide her mother Maria with a much-needed child to project her maternal feelings onto. Indeed, one of her Savoyard ladies, Tomasina de Rossi wrote in her diary,”The Duchessa Maria is so happy to have a living child, she even feeds her with her own breast, something which the Prince, though unhappy with, tolerates to keep his wife happy.”

In Anjou, Prince Jean Duc d’Anjou and Suzanne de Bourbon had their second child, a girl named Blanche, for his mother the Dowager Queen on October 15th. Sadly, the child was delivered two months early, and would die in her mother’s arms just nine days after her birth, causing great grief for her parents.

In the Holy Roman Empire, Phillip of Austria had their fourth child in late August, a stillborn daughter, much to the young couple’s sadness.

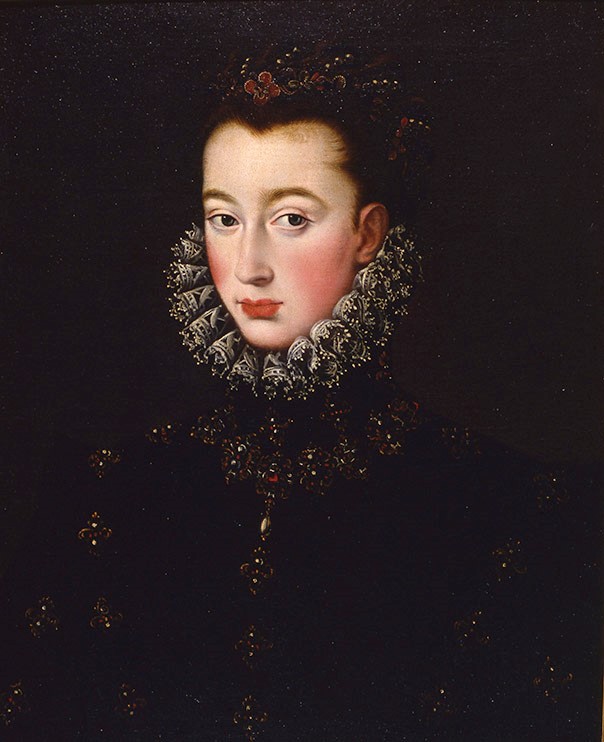

In the Duchy of Milan, the year would start well enough, as in the month of June, Massimiliano of Milan, son and heir of his father wed Eleanor of Austria, youngest surviving child of Charles V and Anne of Bohemia and Hungary. The marriage, while not particularly loving, was harmonious enough, with no major arguments, and would bring Milan a valuable protector in the Holy Roman Empire. The two were also fairly attractive, with Massimiliano having dark hair, and a smooth shaved face, while the Archduchess Eleanor had very delicate features and brown hair once described as,”One of the most daughters of the Imperial house, perhaps only surpassed by her aunt Margaret of Austria in her own younger years.” In spite of this the two were rather different in personality, with the lively and energetic Sforza preferring his young and lustful mistresses and courtesans to his gorgeous, yet staid wife. Isabella of Aragon, the Dowager Duchess of Milan, though happy for her grandson’s marriage, had been in increasingly poor health over the past six years, with painful lumps on her breasts (a sign of breast cancer) and on November 15th, she died of her illness, her suffering at an end. It has been said that her last words were of her dearly departed husband, Massimilano I of Milan, who had predeceased her eleven years ago, with chronicler Roberto Strossi writing,”The Duchessa gasped, and in her last moments said ‘I am coming to be with you Massimiliano, I am sorry that it has taken so long.’”

Across the Alps, in Bavaria, Albert of Bavaria would become Albert V after the passing of William V, the father he despised for his haughty cruelty to his wife Christina on March seventh. It has been widely suspected that Albert poisoned his father, for he died of violent diarrhea, convulsions, and a heart attack, after eating a salad with purple flowers, consistent with the use of the deadly Foxglove plant. Despite these rumors, Albert V would never be punished for this, and his mother the Dowager Duchess Margaret was soon shipped off to live in a local convent… It has been assumed that Margaret of Savoy may have accused her son of murdering his father and was removed from Bavarian court to keep her from spreading rumors, though her son would allow her to visit him and her grandchildren.

Far to the Northwest, in England, Prince Jasper, Duke of Somerset arranged a grand match for his youngest daughter by his first wife. Said match would be with her second cousin, Henry Tudor, son and heir of Prince Henry, Duke of York. He would also have his fifth, and second to last child in this year, a son named John. Sadly, little John Tudor would die a day after his birth, on June 10th, of an unexplained illness.

Eleanor of Austria, often regarded as one of the most beautiful princesses of her time

Massimilano of Milan

To the west, in the Kingdom of Portugal at the Ribeira Palace Manuel, Prince of Portugal had his second child, with his wife. On December 19th, barely eleven months after giving birth to her first child, the sixteen-year-old Catherine of England, Princess of England gave birth to another son, named Manuel for his father. The birth of a second son, in such rapid succession, was seen as a good omen for the marriage, for even if the Prince of Portugal was still unfaithful to his wife, Catherine of England had proven herself to rather be capable in birthing children. The younger Manuel’s godparents would include three of his grandfather’s siblings, as well as his eldest aunt. Specifically, they were the Infante Afonso, Duke of Beja, the Infanta Beatrice (Beatriz in Portuguese), Duchess of Braganza, and his youngest grand-uncle, Infante Ferdinand, the Duke of Guarda and the Infanta Eleanor, Suo Jure Duchess of Barcleos. The Dowager Princess of Asturias, who had resolved to never remarry (though there were rumors that one of her guardsmen was her lover), had designated her second nephew as her heir to her duchy in her will, and would go on to be exceptionally close with the boy, almost as if she were another mother to him.

To then north, in France there were some vital happenings for the House of Valois, particularly its cadet branches in Orleans and Anjou. Firstly, at the Château d'Amboise Prince Charles, the Duc d’Orleans and Maria, the Duchesse of Savoy would, after ten years of marriage, finally have a child that would live past infancy. Unfortunately, the child, born on February 4th, was not quite the gender that her parents had hoped for, yet little Claude would be well cared for by her parents, and would provide her mother Maria with a much-needed child to project her maternal feelings onto. Indeed, one of her Savoyard ladies, Tomasina de Rossi wrote in her diary,”The Duchessa Maria is so happy to have a living child, she even feeds her with her own breast, something which the Prince, though unhappy with, tolerates to keep his wife happy.”

In Anjou, Prince Jean Duc d’Anjou and Suzanne de Bourbon had their second child, a girl named Blanche, for his mother the Dowager Queen on October 15th. Sadly, the child was delivered two months early, and would die in her mother’s arms just nine days after her birth, causing great grief for her parents.

In the Holy Roman Empire, Phillip of Austria had their fourth child in late August, a stillborn daughter, much to the young couple’s sadness.

In the Duchy of Milan, the year would start well enough, as in the month of June, Massimiliano of Milan, son and heir of his father wed Eleanor of Austria, youngest surviving child of Charles V and Anne of Bohemia and Hungary. The marriage, while not particularly loving, was harmonious enough, with no major arguments, and would bring Milan a valuable protector in the Holy Roman Empire. The two were also fairly attractive, with Massimiliano having dark hair, and a smooth shaved face, while the Archduchess Eleanor had very delicate features and brown hair once described as,”One of the most daughters of the Imperial house, perhaps only surpassed by her aunt Margaret of Austria in her own younger years.” In spite of this the two were rather different in personality, with the lively and energetic Sforza preferring his young and lustful mistresses and courtesans to his gorgeous, yet staid wife. Isabella of Aragon, the Dowager Duchess of Milan, though happy for her grandson’s marriage, had been in increasingly poor health over the past six years, with painful lumps on her breasts (a sign of breast cancer) and on November 15th, she died of her illness, her suffering at an end. It has been said that her last words were of her dearly departed husband, Massimilano I of Milan, who had predeceased her eleven years ago, with chronicler Roberto Strossi writing,”The Duchessa gasped, and in her last moments said ‘I am coming to be with you Massimiliano, I am sorry that it has taken so long.’”

Across the Alps, in Bavaria, Albert of Bavaria would become Albert V after the passing of William V, the father he despised for his haughty cruelty to his wife Christina on March seventh. It has been widely suspected that Albert poisoned his father, for he died of violent diarrhea, convulsions, and a heart attack, after eating a salad with purple flowers, consistent with the use of the deadly Foxglove plant. Despite these rumors, Albert V would never be punished for this, and his mother the Dowager Duchess Margaret was soon shipped off to live in a local convent… It has been assumed that Margaret of Savoy may have accused her son of murdering his father and was removed from Bavarian court to keep her from spreading rumors, though her son would allow her to visit him and her grandchildren.

Far to the Northwest, in England, Prince Jasper, Duke of Somerset arranged a grand match for his youngest daughter by his first wife. Said match would be with her second cousin, Henry Tudor, son and heir of Prince Henry, Duke of York. He would also have his fifth, and second to last child in this year, a son named John. Sadly, little John Tudor would die a day after his birth, on June 10th, of an unexplained illness.

Eleanor of Austria, often regarded as one of the most beautiful princesses of her time

Massimilano of Milan

Rest In Peace Margaret. Such joy she must have had to live and see so much fruit from her union with her dear husband...

Indeed she has, she even got to meet a few of her great-grandchildren too... I must admit that I have spoiled Margaret and Juan, with eight of their nine children living to adulthood, though I think I made up for it with the tragedies their children, particularly Ferdinand, Jaime and Blanca have experienced... Thank you so very much, the Margaret of Austria generation is sadly all but gone, with Juana of Aragon being the only one from it that is still alive..Rest In Peace Margaret. Such joy she must have had to live and see so much fruit from her union with her dear husband...

Rest in peace Margaret at least she has plenty of children to carry on her memory and legacy. Great update

She definitely died at peace with herself, secure in the knowledge that her descendants would remember her as one of the most beloved Queen Consorts Spain will ever see... Margaret also lived to relatively old age here too, having outlived all but one of her sisters-in-law.... Thank you so much!Rest in peace Margaret at least she has plenty of children to carry on her memory and legacy. Great update

Last edited:

Your welcome 😊She definitely died at peace with herself, secure on the knowledge that her descendants would remember her as one of the most beloved Queen Consorts Spain will ever see... Margaret also lived to relatively old age here too, having outlived all but one of her sisters-in-law.... Thank you so much!

How would everyone feel about me doing updates covering every five years instead of one, with family trees accompanying the update? I have been thinking of doing this because writing each update as one year can be somewhat cumbersome, and sometimes little goes on in certain years...

That's good!How would everyone feel about me doing updates covering every five years instead of one, with family trees accompanying the update? I have been thinking of doing this because writing each update as one year can be somewhat cumbersome, and sometimes little goes on in certain years...

Ok, thank you very much for letting me know!That's good!

1550 to 1555

The years of 1550 to 1555 would bring a tumult of events to Europe, especially in The Holy Roman Empire, Spain, Portugal, France and England, when the generation that shaped the first half of the 16th century was dwindling in both numbers and influence.

In Spain, a number of prominent individuals would pass. Firstly, there was news that Marguerite de Valois-Angoulême, Queen of Navarre died alone on the 21st of December, of a lung infection, in the prior year of 1549 at Odos. This would dampen the mood of Christmas Celebrations at the Alcázar de Toledo, giving her pregnant daughter (and even her son-in-law) a profound sense of grief. Despite this, Jeanne d’Albert, Princess of Viana and Asturias would not miscarry as feared, and would give birth to a third daughter, this one named Margarita, on April 29th. Margarita, named for her late maternal grandmother brought great joy to her parents, and was betrothed, almost from birth to Miguel of Portugal, grandson of King Miguel I of Portugal.

Included among the infant’s godparents would be the girl’s paternal grandfather, the aging Ferdinand VI of Spain, her step-grandmother, Queen Philiberta. The other pair of little Maragrita’s godparents were her granduncle, the Infante Juan Carlos, Duke of Cadiz and his wife, Magdalena of Navarre, who was also her grandaunt, as she was Jeanne d’Albert’s paternal aunt. For once the Duke and Duchess of Cadiz seemed almost pleased with each other, for they bore mutual pride towards young Margarita.

One of these godparents, however, would not live long to celebrate the recent success of the Prince and Princess of Asturias. Said, godparent would be the Infante Juan Carlos, Duke of Cadiz, who in the beginning of September was once more stricken with dysentery. Within two days of contracting the illness, the Infante would die on September seventh, his suffering from the painful disease finally at an end.

Speaking of that branch of the House of Trastámara, it would be in this span of five years that Duke Sancho, and Duchess Catherine (Catalina) de Medici would complete their family, with the birth of three more children. These would all be girls; Beatriz born on December 5th of the same year of her grandfather’s death, Carlotta, the second youngest child would be born on April 24th of 1552, just a day after her mother’s thirty-third birthday and lastly, there would be Francesca, who came into the world on March 18th of 1555. In 1553, a year after the birth of their penultimate child, Sancho and Catherine would see their eldest surviving child; Magdalena wed to Rodrigo Ponce de León, son and heir of the 3rd Duke of Arcos. Fortunately, even though it was a political match, it would turn out to be a much happier one than that of Magdalena’s parents, with her husband being described as “Pious and chaste.”, and the two would have the first of their seven children in 1556, a few weeks after her eighteenth birthday.

Death would soon strike the very heart of the Spanish royal family… On August tenth of 1552, at the Alcázar of Toledo, King Ferdinand VI of Spain, who had all but drowned himself in drink at the sorrow of the deaths of his mother, and younger brother, died of what must have been Cirrhosis at the age of fifty-two, after ruling over Spain for thirty-one years. He would join his family members that predeceased him, including his first wife Mary Tudor (María de Inglaterra) and their eldest son Juan, in being buried at the Alhambra.

His eldest surviving son would then become Alfonso XII of Spain, who, like his cousin, Arthur I of England, came to the throne with substantial experience from his time as heir to the throne, at twenty-nine years of age. Alfonso would ensure that little would initially change upon taking the throne, for while he occasionally had a difficult relationship with his late father, he retained most of those that his father had hired as ministers. Naturally his lover, Don Rafael Núñez would be one of the foremost poets in his court and was soon married to a noblewoman; Doña Antonia Enriquez de Toledo (b.1532, d.1590) a distant cousin of the King who, unlike Queen Jeanne, seemed aware of the relationship between their husbands. Fortunately for the two men, the young woman seemed indifferent to the affair, and kept it a secret. Ironically enough, the court would become even more staid in regards to courtly love, with King Alfonso XII demanding that his courtiers keep themselves outwardly chaste, and go to mass with him.

Shortly after taking the throne, King Alfonso would arrange a marriage for his second eldest daughter; the Infanta Catalina, for, while it was believed that Queen Jeanne may be able to bear a son, he wanted to ensure that Catalina, as second-in-line to the throne of Spain, was married to another scion of the dynasty. Thus, he decided that Catalina would be engaged to Ferdinand (Ferrandino) of Calabria, eldest son of his newly ascended cousin, Frederick (Federico) II of Naples, and Marguerite of France, who was roughly five years older than his prospective bride. As for the Princess of Asturias’s marriage, young Maria remained unpromised for a time, for, Alfonso wanted to see if he would have a son, and then plan his eldest daughter’s match accordingly.

Another death occurring within this timeframe would be that of King Henri III of Navarre, who had never remarried after his first wife’s death, apparently resigning himself to his Kingdom becoming one of several within Spain, with same rights and privileges that Castile and Aragon were entitled to.

The Dowager Queen Philiberta, who had a decent relationship with stepson, was well provided for in her widowhood, and would be allowed guardianship of her teenaged daughters, the Infantas Constanza and Ana, before they left Spain for their marriages in France and England respectively.

Portugal for its part would also see plenty of change for the ruling House de Aviz. Perhaps most importantly, the family of Manuel, Prince of Portugal and Catherine of England would rapidly expand in this half a decade. This would include the Infante’s João and Eduarte born just a year and a half apart; João being born on January 14th of 1551, while Eduarte entered the world on June 28th of 1552, with both having godparents in their paternal and maternal grandparents respectively. Fortunately, Catherine of England would have a reprieve of nearly three years before having her fifth child, Infante Henrique, named for her younger brother, on April 9th. Sadly, the infant would die of an intestinal disease within two months of his birth, on June 5th.

Doubly tragic for the Portuguese would be the passing of Miguel I of Portugal, barely a month after his grandson’s premature death. On the nineteenth day of July, 1555 the King, while leading mass with his wife Queen Catherine, suffered a heart attack, nearly dropping the crucifix that he carried. Though courtiers and the King’s doctor rushed forward to see if they could help the old man, they soon realized that they were too late, and that the zealous King Miguel was dead, having been King of Portugal for thirty-three years. His widow: Catherine, and their many children were devastated, and the elder Catherine of England, now Dowager Queen, was said to have worn black for every day of the rest of her long life.

The reign of King Manuel II, to some, seems to have signified a much more hedonistic court (hardly difficult in the dour Iberian Kingdom) than that of his father, due to his mistresses and illegitimate children, to whom he granted much favor. Even some of his officials openly kept mistresses and brought their bastard children to court, something which would have never been tolerated under King Miguel.

Indeed, by the time he took the throne Manuel II had already sired six children out of wedlock, all but one of whom were by his mistress; Teodora de Almeida (b.1522) his youngest children by Teodora were; the prematurely born Antonio (b.1549, d.1550), Joana (b.1549) and Isabella (b.1552) and it is likely that the birth of little Isabella was the true reason for the age gap between the Infantes Eduarte and Henrique; as it has been speculated that Catherine refused to sleep with him for at least a year. By two more mistresses, a pair of sisters; Aldonça (b.1530) and Violante da Gama (b.1537) he would have several more illegitimate children by 1555. By Aldonça he had; Vittoria and Pedro de Portugal born in 1553 and 1555 respectively. His only child by Violante (before she was married to a court official) was Iolanda de Portugal, born shortly before her cousin and half-brother Pedro.

Across the Pyrenees Mountains in France, much would also change, with the birth of more children for King Francis (Francois) and his Austrian Queen, Elisabeth of Austria as well as the arrival of the Spanish Dauphine.

The first of these to come to pass was the birth of two more children to the King and Queen. Firstly, on May 14th, at the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Queen Elisabeth of France went into labor for the seventh time. Fortunately, the thirty-year old and her child would survive the birth, and it would be revealed that she gave birth to a third son, named Antoine for her paternal uncle; Antoine of Austria. Two years later Queen Elisabeth would become pregnant again, but unfortunately in the fifth month of her pregnancy in September, she would deliver a stillborn son, which many (falsely) assumed would be her last child.

It would be one year after this unfortunate event that Constanza of Aragon, eldest daughter of the late King Ferdinand VI of Spain and Philiberta of Savoy, would arrive in France to wed the Dauphin Louis in 1553. Fortunately for Constanza (Known to her new people as

Constance d'Espagne) she would not initially face the same difficulties that her Austrian mother-in-law had experienced as Dauphine, for it seemed that this marriage would secure peace between France and Spain, though her considerable dowry no doubt played a role in how well she was accepted. Her husband, the fifteen-year-old Dauphin, seemed to dote on his older bride, and was, at least in the beginning of their marriage, faithful to her. The two were even somewhat similar in their coloring, as both were pale and blonde, inherited from their (Constanza’s) father and (Louis’s) mother, respectively. When it came to their personalities the two were also rather compatible. Constanza, like her mother, Philiberta was high-spirited, but unlike her parents she was of very humble demeanor. The Dauphin Louis for his part was dutifully religious, not as pious as his father but he was no unbeliever, while he inherited his Austrian mother’s charm and sharp sense of humor.

Preparations were also made in regard to Prince Charles, the King of France’s second son. The boy, like his father before him, had always been exceptionally pious and austere, thus, it was decided that he would one day enter the clergy. Of course, this could also have some political ramifications, for it was hinted that King Francis hoped that Charles may one day even become a Cardinal in the Church, possibly rejuvenating French influence in the Curia. Upon the death of King Henri II of Navarre in 1555, King Francis turned his attention to the issue of that Kingdom’s succession, quietly preparing his armies for the war that he would soon initiate in the coming years…

Prince Charles, the Duc d’Orleans and eldest of the King’s younger brothers would also be engaged in a flurry of activities, procreation being foremost among them. By Maria of Savoy, he would have three more children in these years; a long-awaited son named Phillipe, born on April 12th of 1551. Next would be a daughter named Louise, born on the first of July in the year 1552 and lastly, there was their penultimate child; a son named Louis, who was born on January 20th, and died the same day.

The Duc d’Orleans of course, also spent this time producing several bastard children with his mistress Fillipa Duci as well. They had three such children within these five years. Among them were: Marguerite born on January 11th of 1550, Charles born on August 20th of 1552 and Robert born on March 25th of 1554.

Prince Jean, Duc d’Anjou would have several children with his wife; the Duchesse Suzanne. Firstly, in June of 1551 Suzanne gave birth to a stillborn daughter in the sixth month of her pregnancy. Three years later, on September 19th she managed to give birth to another living child a daughter named Agnes for her her late sister-in-law, Agnes, the Duchess of Lorraine.

In the Duchy of Bourbon meanwhile, would change hands during this period. Before that happened, the Duchy’s heir; Jean de Bourbon, married his betrothed Bona d’Este, in what initially was a happy and loving marriage. Bona, as a member of the wealthy d’Este family brought a large dowry with her from Ferrara as well, and the fact that the Duchy’s heir married a foreign noblewoman no doubt boosted the prestige of this branch of the House de Bourbon. To make matters even better Bona quite rapidly fell pregnant within the first months of her marriage. The serious and intelligent brunette soon found herself as one of the foremost women in the duchy, only behind her mother-in-law. On December 3rd of 1550 she would go into labor for the first time, one that was surprisingly easy for a first birth. The child would turn out to be a living son, named Peter (Pierre) for his paternal grandfather.

Shortly that however, Duke Peter III’s wife; Eleanor de Foix, suffered a miscarriage in April of 1551, and this would be her last child. This unhappy event would be followed by two more for the family; Bona would give birth to a stillborn son in the seventh month of her pregnancy in October of 1551. She would then miscarry her third child in April of the following year, a traumatic event that nearly killed the young woman. Jean de Bourbon for his part took a pair of mistresses. The first, was the beautiful and mature Diane de Poitiers (b.1500, d.1566) ,thirty-five years his senior. The other, was Nicole de Savigny (b.1535, d.1590) who shared a birth year with Jean and his wife. Bona took more insult from Nicole’s presence as her husband’s mistress, as she viewed Diane as little more than “An old whore.” The initially happy marriage soon broke upon the birth of Jean de Bourbon’s illegitimate child by Nicole de Savigny, a girl named Claude on September 14th of 1553. Duke Peter III made an effort to chastise his son for his infidelity, but ultimately the man’s efforts were unsuccessful.

Another member of the De Bourbon family would also be wed in these years. Said individual was Anne de Bourbon, eldest child of Duke Peter III and his second wife Eleanor de Foix. In April of 1551 she wed François III d'Orléans, Duke of Longueville (b.1535, d.1590), after he recovered from a brief period of severe illness. The marriage would be a very loving one, and François did not even take any mistresses, and over their long marriage they would have six children, all but one of which would survive infancy.

Things would take a turn for the worse for the family when Peter III, Duke of Bourbon, died on May 22nd of 1554. This occurred when the man was riding his horse near the outskirts of Paris. A snake startled the creature, and it bucked wildly, flinging the Duke from his back into the River Seine. The Duke, who did not know how to swim, soon drowned despite the best efforts of his attendants. Peter III, Duc de Bourbon was only forty-five years old when he died and his devastated widow; Eleanor de Foix, would soon take the veil as a nun, taking solace in her religion.

The new Duke of Bourbon also directed his only brother; Jacques de Bourbon, fatherless at the tender age of seven, to begin a theological education, hoping that the boy could eventually enter the clergy. In the absence of his parents, young Jacques was raised by his elder half-sister, Marguerite (b.1530) the eldest living child of his father by his marriage to Isabella de Foix. Marguerite had remained unmarried, partially due to financial concerns of paying for her dowry, but also because Nicolas, Duke of Mercœur (b.1524) jilted her to marry the older Marguerite d’Egmont (b.1517, d.1554). Normally, an unwed daughter such as her would have joined a nunnery at this point, yet, as his eldest child by his first wife, the later Pete III treated very tenderly, and allowed her to stay as a spinster in his court. Thus, Marguerite was very close to her younger half-brother, and would also supervise the education of her nephew Peter.

Bona d’Este would not be the only girl of her family to marry a French Duke. Her younger sister, Giovanna d’Este would arrive in 1554 to marry Francis II, Duke of Guise, this would be a decidedly happy match, for the Duke was enchanted by his beautiful young bride, and while Giovanna was happy to be in France with her elder sister Bona, it also didn’t hurt that her husband, despite being twenty years her senior, was handsome and athletic.

The de Foix family, which ruled over Nemours would also have some substantial accomplishments. Foremost among them was the arrangement of an incredibly advantageous marriage for Duke Jean’s eldest son Gaston. This match came in the form of a betrothal between Gaston, and Anne d’Orleans (surnamed so to differentiate her from her Valois-Orleans half siblings) illegitimate daughter of Prince Charles, the Duc d’Orleans and also niece of King Francis II.

Another match for the De Foix family would be that of Marie de Foix, who would marry Nicolas, Duke of Mercœur, as his second wife in 1555, after the death of Marguerite d’Egmont, ironically the woman that he had married instead of her cousin Marguerite.

Charles de Foix, second son of Jean de Foix, Duke of Nemours would also be given a prestigious engagement, with a daughter of Antoine de Noailles, first Comte de Noailles. Antoine was not only a Count, he had also served as French Ambassador to England, so the marriage between Charles and Marie de Noailles (b.1543) provided both good pedigree and extensive connections.

The Dauphin and Dauphine would not be the only prominent marriage, for several others in or around France would wed, or be betrothed during these years. Among them was Princess Agnes, the middle daughter of the Dowager Queen Blanca and the late King Francis I. Agnes, nearly sixteen, departed the royal court for Lorraine in March of 1552, where the vivacious red-haired girl wed the brown-haired Duke Charles III of Lorraine. The Duke and Duchess seemed to get along rather well, though at first it was perhaps more similar to a friendship than a loving marriage. Nonetheless, the two were faithful to one another, and seemed to have remarkable reproductive chemistry, within just a few months of the marriage she became pregnant.

Agnes was also close to her sisters-in-law; Catherine, who was betrothed her brother Henri, the Duc D’Angolueme, and the unwed younger ones; Isabella and Philippa. She had even developed a close friendship with her mother-in-law Mary of England, the Dowager Duchess, even though the young woman was initially worried that the protective woman (Charles was her only living son) would be jealous of her, but Mary Tudor warmed to her in time.

Unfortunately, Agnes would not be happy in Lorraine for long. The first of several tragedies to befall her would be the premature birth of her eldest child; Marie of Lorraine on November 16th. Little Marie, named for her paternal grandmother, and born three months would not live for long, dying the morning after her birth. This tragedy would cause a torrent of grief for the court, especially for the girl’s young mother, who almost certainly suffered from depression after the death of her first child. Two years later Agnes was pregnant again, but instead of the predicted joy at the arrival of another child she made a dire prediction that,”I will either die giving birth, or bury every child I bring into this world.” Sadly, she would, in time, be proved right. Months later, on August 27th of 1554 she gave birth to her second and final child, after a grueling seven-hour birth. She named the girl Blanche, for her mother, the Dowager Queen of France who had comforted her by staying in Lorraine with her daughter throughout her pregnancy. The child would not have a mother for long though, for two hours later, Agnes of France, Duchess of Lorraine bled to death, expiring in her mother’s arms.

Her grieving widower would have even more cause for misery, as several months later his mother Mary of England, one of Blanche’s godmother’s (along with the girl’s other grandmother namesake) , died on the seventeen-day of November. It has been concluded that the forty-four-year-old had been stricken with uterine cancer, her health likely worsened by the grief of her son. By the beginning of the next year, Charles III, though hating that he had to do so, resigned himself to the fact that he would have to remarry. Fearing that the male line of his family would die out, and Lorraine by picked apart by the French King and Holy Roman Emperor. The young man, now one of the most eminent bachelors in Europe had a number of options; ranging from his English kin, relations of the Holy Roman Emperor, French Princesses or a woman from one of the wealthy Italian Duchies… He ultimately decided that he would marry a French Princess, to secure his lands from potential French or Imperial aggression. Of course, it has been rumored that his first wife Agnes, in her will, implored him to marry one of her nieces so that they too could have such a good husband.

The Frenchwoman that Charles III picked as his second wife, was Princess Louise of France, seven years his junior and eldest surviving daughter of King Francis II and Elisabeth of Austria. King Francis, though saddened by his half-sister’s death, was eager to follow her will, especially as it gave him the opportunity to secure a fine match for his daughter. Thus, it was agreed that Charles III would marry Princess Louise in 1557, shortly after her fifteenth birthday. Apparently having to wait appealed to the man, who needed the time to care for his daughter and young sisters; as well as to mourn Agnes’s death.

Across the English Channel, in England, the Infanta Ana, youngest daughter of King Ferdinand VI of Spain and Philiberta of Savoy would arrive to wed Henry, the Prince of Wales, in 1553, when in the month of March, the fifteen-year-old Prince of Wales married the Infanta, in her seventeenth year at Richmond Palace. The Infanta Ana was said to have smirked in satisfaction as she exited her carriage and laid eyes on the many guests. The Prince of Wales was also quite pleased by his bride, and the two energetic teens danced multiple times during the wedding, and there was no doubt that they engaged in other athletic activities when they entered their chambers.

Such enthusiasm hid an uglier side of the attractive young couple. The new Princess of Wales was vain, arrogant, and demanding, as one of her lady’s Susan Stafford, daughter of Henry, the Duke of Buckingham recorded,”She gets incredibly angry if she does not get what she wishes. She slapped her seamstress for missing a small stich, and heaven forbid someone should discuss religion in her presence. One of her Spanish women; Doña Ines has told me that the Princess may be more beautiful than her sister Constanza, but she has inherited the worst qualities of her parents. God help us when she sits on good Queen Anne’s throne.”

The Prince of Wales for his part had a great love for the company of women. This would initially be limited to his wife, but during the first of her many pregnancies he turned his attention to the fourteen-year-old Jane Seymour “The younger” (Named for her aunt the Countess of Sussex) who soon became his favorite mistress. The Princess of Wales flew into a rage when she learned the news, apparently threatening to run the Lady Jane through with a sword. Fortunately, Ana found herself unable to follow through with her threat, and on August 19th she would give birth to her first child. The child, to the disappointment of many who thought the English succession insecure, was a daughter. She would be named Anne for her mother the Princess of Wales, and her paternal grandmother: Anne of Cleves. Among her godparents were her paternal grandparents; King Arthur and Queen Anne, as well as her maternal aunt the Dauphine Constanza of Aragon and her husband the Dauphin Louis, in an effort to try and cultivate decent relationship with the French king.

In the Duchy of Somerset, the Royal Duke, Prince Edmund would find himself stricken with smallpox four days after the birth of his youngest child Charles. He would linger on for another day, until slipping away on June 19th, adding more sadness for his son Jasper, whose wife Frances had suffered a miscarriage in the previous year. His young widow, Catherine Howard, the Dowager Duchess of Somerset was well treated by stepson, and was even allowed guardianship of her children by Edmund, even after she remarried to John de Vere (b.1516, d.1557, dying of a sudden illness) the Earl of Oxford as his second wife in 1553. This is likely because duke wanted to save some money on the upkeep of his half-siblings, and also out of a genuine desire to see the woman happy.

Catherine Howard soon found herself one again married to another older man of status, and all in all, was forging a good life for herself and her young children. The thirty-year-old woman now found herself a Countess with a husband who, if not quite as loving as her first, still treated with respect, and she once more was stepmother to several young children.

As for her children by her first husband, the four that lived to adulthood would all achieve some prominence, given that they were cousins to King Arthur. Shortly after his fourteenth birthday, her eldest son Edmund, who in his youth was called Edmund “the younger” to differentiate himself from his father, was created Earl of Leicester by his royal cousin the King. Shortly after this the King had arranged for a good double match for the boy and his only full sister; Anne. Edmund was betrothed to Elizabeth Brandon (b.1547) while Anne (b.1547) was to be wed to Elizabeth’s older brother Charles Brandon (b.1543) , the second Duke of Suffolk, grandson and successor of his namesake grandfather Charles Brandon (b.1484, d.1545) and Elizabeth Grey, Viscountess Lisle (b.1505, d.1553). Catherine’s other two children by her first husband; George (b.1543) and Charles (b.1551) for their part were trained to become members of the Catholic Clergy, and both would eventually become bishops.

Catherine Howard would also have the first of her two children by the 16th Earl of Oxford in 1554, a daughter born on October 5th, named Joyce for her maternal grandmother.

Duke Japser, the 2nd Duke of Somerset and his dear wife; Frances de Vere would complete their large brood of children in this year and arrange advantageous matches for their older children. Other than the miscarriage in 1550, they would have two more children. The long awaited second son named William was born on September 25th of 1551, and would soon be engaged to Alice Parr, only living child and heiress of William Parr, the Earl of Essex, who was a year his senior. Their youngest child: Cecily would be born three years later, on December 17th, a few weeks after her mother’s thirty-seventh birthday.

The matches for their older children would be suitable enough, if not excellent. Their eldest child, Elizabeth would be wed to Thomas Stafford (b.1533), the son and heir of Henry Stafford, the 4th Duke of Buckingham, who was also a second cousin to his wife. Their son Henry would be betrothed to Margaret Howard (b.1541) daughter of the arrogant Henry Howard, the fourth Duke of Norfolk. Their younger daughters Mary and Catherine were slated to one day become countesses through their marriages: Mary (b.1546) to Henry Hastings (b.1535) heir to the Earldom of Huntingdon and Catherine (b.1548) to Charles Neville (b.1542), the Earl of Westmoreland’s heir.

Prince Henry, the Duke of York would have his final child with Amalia of Cleves in 1550. Sadly, young Edward, born on March 16th, would die five months after his birth, on August 26th.

The dead boy’s parents would soon find themselves preoccupied with other matters; chiefly the marriages of their children.

Young Henry Tudor for his part would wed his second Cousin Margaret Tudor, also known as Margaret of Somerset (b.1531), the youngest child of the late Prince Edmund and his first wife Katherine Stafford. Unlike his father Henry would prove to be a loyal and doting husband, and Margaret, four years his senior seemed to welcome the affections of her young husband. The marriage bore fruit quickly enough, with a child miscarried in March of 1552 and a daughter; Catherine, born on April 4th of 1554. The young man was, despite the frustrations of his father, perfectly happy that his wife had given birth to a daughter, and besides, he was assured they would have more children, she was barely in her twenties when young Catherine was born.

The second eldest child of Henry and Amalia to live past infancy, Joan Tudor, was wed at fifteen in 1555 as second wife of Henry Courtenay, 1st Duke of Exeter (1), who also happened to be a distant cousin. Courtenay’s first wife; Mary Basset (b.1525, d.1553) had died giving birth to her third child by him, stillborn like all the others, and so the man eager to beget sons, married young Joan. Joan’s husband was occasionally unfaithful to her, but he produced no known illegitimate children, and otherwise treated her well.

Cecily Tudor, penultimate living child of the Duke and Duchess of York would make a grand match herself. In 1552, she was engaged to her second cousin, Arthur Stuart, second eldest son of James V of Scotland. The marriage was a mostly successful attempt to secure peace between England and Scotland, for Cecily was niece to the King of England, and she often managed to smooth over tensions between the two Kingdoms.

The two other daughters of Henry and Amalia; Mary (b.1544) and Anne (b.1548) would both join nunneries, the former more enthusiastically than the other, satisfying the vow of their grandmother; Catherine of Aragon, that one of her granddaughters would join a nunnery in thanks for the Catholic Church allowing the crown to tax its lands in England.

To the north, in Scotland, James V would prepare his youngest legitimate sons: Alexander (b.1546) and John Stuart, born at Holyrood on June 24th of 1551, for a church career. He had also arranged for his only surviving legitimate daughter; Margaret (b.1547) to be engaged to James Hamilton (b.1537), the Earl of Arran’s son and heir. It was after the negotiations for his daughter’s marriage that King James soon fell terribly ill. The disease that he suffered from, was almost certainly Cholera, and after four days of clinging to life, the King died at the age of thirty-eight. It was a moment that could have resulted in pandemonium; A boy of nine was now king. Yet Alexander Stuart, Duke of Ross, uncle of the new King took calm and decisive action, ensuring that a fair and balanced Regency Council was established, with he, as the eldest uncle of the King, being the head of said council, though he did allow his sister-in-law, Isabella of Navarre, the stepmother of James VI, a seat on the council.

In the Alps of the Duchy of Savoy, the year 1550 would start with a death. That death would be that of Teresa de Bivero (b.1487, d.1550) the mistress of the late Philibert II of Savoy. She died in her sleep on January 15th of 1555, and, in her characteristic closeness with the children of her dead love Philibert, and close friend Maria of Aragon, divided her wealth evenly amongst her two bastard children and the children of Philibert and Maria.

That death would not bode well for the rest of the year, for Joan of France (Jeanne in French and Giovanna in Italian) beloved wife of Phillip of Savoy would give birth to their first child Louise on August 5th. Sadly, little Louise would die, likely of an intestinal disease, four months later on December 11th, causing heartbreak for her young parents. Fortunately, the two would go on to have two more children in the span of four years: a son named Philibert born on July 8th of 1552, and a daughter named Elisabeth on March 21st of 1554. Both of the children would have their paternal grandparents as godparents, as well as their half-uncle Francis II of France and his wife Elisabeth of Austria, Queen of France being another pair of godparents

Phillip and Joan would not be the only ones to have children, as on November 15th of 1552, Elizabeth of England, the thirty-seven-year-old Duchess of Savoy would give birth to her eighth final child, a daughter named Catherine for her own mother. Her godparents were almost certainly picked by the Duchess Elizabeth, as they were all of her family. This included her brother King Arthur I of England, his Queen, Anne of Cleves as well as her youngest sister Edith, Crown Princess of Denmark and her husband, Crown Prince John.

In Italy, the various ducal families would also expand and contract in these years.

In Milan, Massimiliano of Milan, the heir to the duchy would have a number of children, both legitimate and illegitimate. By his wife: Eleanor of Austria he would have three children; Ludovico, who was born on February 5th of 1550. Among the child’s godparents were his paternal grandparents; Ludovico II, Duke of Milan, and Renee of France, the Duchess of Milan. The other pair were another natural choice, his maternal grandparents, Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, and Anne of Bohemia and Hungary, the Holy Roman Empress. Tragically the baby would die six months after his birth, on August 18th, dashing hopes that the thriving boy would one day become Duke of Milan. Still, his parents were young, and they would soon prove that they would be able to have more children. Two years later, on June 1st of 1552, Eleanor of Austria went into labor for the second time. Though difficult, she and her children would survive it, and she would deliver fraternal twins of matching names: A son named Giovanni for her husband’s uncle that died in infancy, and a daughter, Giovanna, who happened to be named after Eleanor’s grandmother, the Dowager Holy Roman Empress. The young couple were extremely pleased to have two living children in three years of marriage, yet it was during the pregnancy that Massimiliano’s eye wandered. His mistress: one Hortensa Sissardi (b.1535), a former courtesan had attached herself to the Duke of Milan’s son and heir in the hopes of gaining status for herself. Status would not be the only thing she would get from this relationship, for she would soon find herself pregnant with her lover’s bastard child. On July 15th of the year 1553, she gave birth to an illegitimate daughter, who, her paramour would recognize and name Maria. They would have another child two years later on October 4th of 1555, this time a son named Martino. Eleanor, though displeased by her husband’s infidelity, kept her dignity.

In the neighboring Duchy of Ferrara, Ercole II’s son and heir Carlo would come of age, and wed his betrothed: Maria of Savoy. Young Carlo had already developed something of a reputation for womanizing, despite his delicate looks, and took his comely bride to his bed enthusiastically enough. Still, even if he did like Maria of Savoy, he was still frequently unfaithful to her, and on May 14th, just a month after their wedding, his eldest child, a bastard son named Francesco was born to one of his many mistresses. Maria was rather indifferent to this, and it has been speculated that she was not strongly attracted to anybody, man or woman. Still, Maria would due her foremost duty with aplomb, giving birth to two children in the first five years of her marriage. Their eldest, a girl named Leonora was born on September 19th, and sadly, died in her sleep the next day. Nearly three years after this crushing loss, Maria would birth another daughter, named Caterina for her paternal grandmother, Catherine of Austria. Naturally Catherine of Austria, and her husband, Ferrara’s duke, Ercole II were the godparents of the child, as were two of Maria’s siblings: Margaret, who had just been engaged to the recently ascended Duke of Mantua, and Henry. Her husband was, to say the least, rather disappointed by the fact that he only had a daughter, but fortunately for Maria and her daughter, her father-in-law did not share such concerns., and provided for them generously.

In nearby Mantua, Guglielmo I of Mantua would marry Margaret of Savoy, in 1555, what would prove to be a fairly loving, and calm marriage.

Juana of Aragon, Grand Duchess of Florence and elder sister to the King of Spain, would give her husband Lorenzo several children in these five years. They would be: Luisa, who sadly was born on January 28 of 1550, and died the same day. Alessandra, who was born on June 9th of 1553, and Clarice, who, like her oldest sister, would die shortly after her birth on November 5th.

To the south, in Naples, the powers of kingship would be peacefully transferred from King Ferdinand III of Naples, to his eldest Frederick when the sixty-one year old died of a heart attack on October 20th of 1550. His widow, Maria of Aragon, who hated her late husband, shocked the royal court when, in the next year, she took a lover, Vincenzo Bellarmino, the brother-in-law of Pope Marcellus II. Fortunately, her son Frederick II understood his mother’s reasons for doing so, and took no action against them.

Speaking of which, King Frederick II and his beloved wife Marguerite of France would have three more children over the course of this half-decade. Caterina, who was born and died on December 1st of 1550, Francesco, who was born on July 18th of 1553 and a stillborn son born in January of 1555.

In the Duchy of Cleves, Duke William I “The Rich” and his young wife Wilhelmina would get to the vital duty of producing heirs, having four children in five years. These were: Marie Eleonore, born on June 16th of 1550, another daughter named Anne for the Duke’s sister: The Queen of England was born on August 16th in the year of 1552, and finally, a son named John was born May 28th of 1554. Sadly, their fourth child, a daughter named Margaret, would not thrive like her older siblings, as she was born prematurely and died a day after her birth on October 5th of 1555.

Albert V of Bavaria and his Duchess Christina had three more children in these years. A daughter: Kunigunde who was born on June 5th of 1550, a son Albert who died on the day of his birth: January 8th of 1552 and another son named John who entered the world on August 1st of 1555.

King Vladislaus III of Hungary would find himself lacking sons in these years. His second, and final son, Vladislaus the younger came into the world on March 15th of 1550. Unfortunately, the child would live for less than two weeks, dying on the 24th of March. Queen Ippolita’s fifth pregnancy would see a daughter, Joanna, born on November 9th of 1554. Luckily, little Joanna would prove to be healthier than her older brothers, and would live past infancy.

In neighboring Poland, the coming of age of King Sigismund II would bring relief to his grandmother; The dowager Queen Eleanor, and his uncle Prince Casimir, for it meant that he could finally be wed and start producing heirs. Thus, in December, just days before his fifteenth birthday, Sigismund wed the Princess Margherita of Naples at Krakow. Sigismund, dark haired like his parents would be rather enamored with the pretty, if spindly, blonde girl. Within two years of the marriage, Margherita gave birth to a child. The princess Eleanor, would be born on February 5th of 1554, much to the delight of her young parents.

In Denmark, Crown Prince John would have his final child with Edith of England on June 14th of 1551, a daughter named Catherine for her maternal grandmother. Just a few years after this, tragedy would strike, for John's eldest grandson, also named John, the child of Christian of Denmark and Catherine of Austria, would hours after his birth on February 19th of 1555.

In nearby Sweden, Prince Eric, the Duke of Kalmar would have four children in these years, half of whom were by his half. By, his favorite mistress, Sigrid Einarsdotter he had (b.1531) he had Cecilia, born on April 13th of 1550 and John, born on April 21st of 1554. Finally, when he turned his attentions to his wife, Anna of Mecklenburg, he would have two more children: Gustav born on December 9th of 1551 and a little daughter; Hedwig who died two days after her birth on June 15th of 1553.

In the Holy Roman Empire, the family of Phillip of Austria and Isabella of Aragon would also grow, though not as exponentially as several others. The young couple would have two children in these five years: Phillip and John, with the former born on December 4th of 1552 and the latter on August 12th of 1554. The boys would have godparents in the form of their uncles and their wives; Maximillian of Austria and Catherine of Hungary, as well as King Alfonso XII and Jeanne d’albert, Queen of Spain. Sadly, Phillip the younger would not live to see his first birthday, dying of an unknown ailment on October 18th of 1553. It was also in this time that the second youngest of the Emperor’s daughters; Catherine left to wed the eldest son of the Crown Prince of Denmark; Christian of Denmark (Known as Den yngre prins meaning; the younger Prince, in respect to the fact that he was the eldest son of Crown Prince John (Hans).

One more notable event to occur in the Holy Roman Empire was the death of Juana of Aragon, the Dowager Holy Roman Empress on Good Friday of 1555 (April 12th) at the age of seventy-five. Her physical state had been deteriorating for nearly a year, and when the old woman was found dead, her grandson Phillip, who loved her dearly remarked,”While I wish not to say this, perhaps this for the best, for she no longer suffers.”

In Norway, Prime minister Helga Solvisdotter would find herself easily reelected in 1553, winning roughly eighty percent of the vote (To Bodil Anresson’s (b.1510, who won 20%) , for her more insular policy, of focusing on the wealth of Norway and her colonies (Which expanded during her years as Prime Minister) proved to be a popular one. To put it simply, the Norwegians were tired of war, and preferred the benefits of peace to deprivations of war.

The Second Schmalkaldic WarThe execution of the Duke of Hesse, for rebelling against Charles V three years prior, would, ironically, spark yet another, much stronger rebellion against the Holy Roman Emperor and his authority. Starting in 1551, and ending in 1554, the Second Schmalkaldic war would have rather devastating consequences for the Emperor Charles V, for even more of the Imperial Electors rose up in rebellion. Those who rebelled were led by Maurice, Elector of Saxony, who had previously helped Charles V, and was known for his cunning, and once again fought for the side that he thought would win. He had good reason to think so too. Among the fellow rebels were: Albert, Duke of Prussia, Joachim Hector II, the Elector of Brandenburg, Albert Alcibiades, Margrave of Brandenburg-Kulmbach, Otto Henry, the Elector Palatine, John Albert I, Duke of Mecklenburg

Phillip I, Duke of Pomerania and perhaps surprisingly, William I, Duke of Cleves, whose moderate Catholicism had previously made him indifferent to the Emperor, but now joined the rebellion to depose what he viewed as,”A tyrant who would kill us all and take lands of the rightful electors.” The Electors would not be alone in their struggle, for the Republic of Norway, though uninterested in directly taking part in war, was eager to provide indirect support, mostly in the form of shipments of weapons and armor. More importantly, Gustav I, King of Sweden would directly intervene. As for Charles V, he could call upon comparatively few allies, for his son-in-law, King Francis II was preoccupied in planning to move against Protestants in his own country, while the Duke of Bavaria was strictly neutral. His nephew, Vladislaus III of Hungary also sent a few thousand troops, but not much else, for he did not wish to weaken his own kingdoms position.

The war would get to its proper start rapidly, as in March of 1551, Otto Henry, the Elector Palatine of the Rhine, with a substantial host of 8,000 men (along with smaller war bands from the Duke of Cleves), raided the Burgundian Netherlands, conquering and plundering rather vast swathes of prosperous territory, stopping short of large cities like Rotterdam and Amsterdam. These probing attacks would prompt the Emperor to devote thousands of troops to driving the old Count off, which, while somewhat successful, Palatine and his men would manage to evade the Imperial forces, meaning that this caused the Emperor to divert forces from other, more crucial, fronts. The arrival of 10,000 Swedish troops in Mecklenburg would help the local Duke beat back an Imperial force of 14,000 men, when on July 15th of 1551, he and 13,000 troops prevailed over them, suffering 2,000 casualties for five thousand Imperial losses.

Imperial troops would gradually be driven south of Thuringia, with 12,0000 troops commanded by Phillip of Austria being defeated by a rebel force of equal number, commanded by the more experienced Maurice of Saxony at the Battle of Thule on April 4th of 1552. There would be a number of other minor battles and skirmishes over the next two, mostly victories for the Schmalkaldic League, but the Emperor’s forces, when commanded by his youngest brother, Antoine, had occasional victories.

The death knell for the Emperor’s cause would come on October 2nd of 1554, outside of Fulda, where Imperial troops were trying to lift the siege of the city. Said attempt was unsuccessful, and 15,000 Imperial troops would have to face 17,000 men of the Schmalkaldic league, commanded by both Maurice, the Elector of Saxony, and William, the Duke of Cleves. The imperial troops, lead by Phillip of Austria and his uncle, the Archduke Ferdiand fought bravely, but were no match for the determined zeal of the rebels. At the end of the day 4,000 Imperial troops were killed, another 8,000 captured and among the captured were Phillip of Austria and his eldest uncle, while their enemies suffered just 2,000 losses. The Emperor on hearing of the defeat, was said to have fainted. When he finally recovered, he decided that, for the sake of the Empire and kin, he would negotiate terms of surrender. A month later, he met with the rebels outside of Halle, known as the Diet of Halle, for it included all of the Electors to negotiate with them. It is worth noting that the French King, his, son-in-law, also lent the Emperor substantial diplomatic support, with the King of Hungary doing the same, with both threatening to lend their full support should the Habsburg family be deposed.

Thus, the terms were something of a compromise.

II: Several of women of the Habsburg family are to wed the lords who led the Schmalkaldic league, all of them nieces of Charles V. Otto Henry, the Elector Palatine (b.1502) was wed to young Anna von Habsburg (b.1530) , his heir presumptive, Louis (Ludwig, b.1539) was engaged to Clara von Habsburg (b.1543) while Augustus, who would eventually succeed his brother Maurice as Elector of Saxony, married Charlotte von Habsburg (b.1538) , another niece of the former Emperor.

III: Tolerance of Lutheran’s by Catholics, and Catholics by Lutherans, with Catholic lords being allowed to charge their Lutheran subjects, an additional tax for their protection, with Catholics being able to do the same.

With this Habsburg rule over the Holy Roman Empire was saved, at the cost of Charles V giving up his crown. To this day there is still fierce debate over the rule of Charles V: Was he a tyrant, who bludgeoned his enemies mercilessly and should have never been elected? Or, was he a deeply troubled man, who, in the end, did what was best to save the Empire? The truth, is likely somewhere in between, yet, in any case, the reign of Charles V ended in November of 1554, and his son, Phillip II, became Emperor.

Louis, Dauphin of France

Constanza of Aragon, Dauphine of France

Jean III Duc de Bourbon

Bona d'Este, Duchesse de Bourbon

So yeah, 26 pages in word, brought to you by coffee and poor life choices

In Spain, a number of prominent individuals would pass. Firstly, there was news that Marguerite de Valois-Angoulême, Queen of Navarre died alone on the 21st of December, of a lung infection, in the prior year of 1549 at Odos. This would dampen the mood of Christmas Celebrations at the Alcázar de Toledo, giving her pregnant daughter (and even her son-in-law) a profound sense of grief. Despite this, Jeanne d’Albert, Princess of Viana and Asturias would not miscarry as feared, and would give birth to a third daughter, this one named Margarita, on April 29th. Margarita, named for her late maternal grandmother brought great joy to her parents, and was betrothed, almost from birth to Miguel of Portugal, grandson of King Miguel I of Portugal.

Included among the infant’s godparents would be the girl’s paternal grandfather, the aging Ferdinand VI of Spain, her step-grandmother, Queen Philiberta. The other pair of little Maragrita’s godparents were her granduncle, the Infante Juan Carlos, Duke of Cadiz and his wife, Magdalena of Navarre, who was also her grandaunt, as she was Jeanne d’Albert’s paternal aunt. For once the Duke and Duchess of Cadiz seemed almost pleased with each other, for they bore mutual pride towards young Margarita.

One of these godparents, however, would not live long to celebrate the recent success of the Prince and Princess of Asturias. Said, godparent would be the Infante Juan Carlos, Duke of Cadiz, who in the beginning of September was once more stricken with dysentery. Within two days of contracting the illness, the Infante would die on September seventh, his suffering from the painful disease finally at an end.

Speaking of that branch of the House of Trastámara, it would be in this span of five years that Duke Sancho, and Duchess Catherine (Catalina) de Medici would complete their family, with the birth of three more children. These would all be girls; Beatriz born on December 5th of the same year of her grandfather’s death, Carlotta, the second youngest child would be born on April 24th of 1552, just a day after her mother’s thirty-third birthday and lastly, there would be Francesca, who came into the world on March 18th of 1555. In 1553, a year after the birth of their penultimate child, Sancho and Catherine would see their eldest surviving child; Magdalena wed to Rodrigo Ponce de León, son and heir of the 3rd Duke of Arcos. Fortunately, even though it was a political match, it would turn out to be a much happier one than that of Magdalena’s parents, with her husband being described as “Pious and chaste.”, and the two would have the first of their seven children in 1556, a few weeks after her eighteenth birthday.

Death would soon strike the very heart of the Spanish royal family… On August tenth of 1552, at the Alcázar of Toledo, King Ferdinand VI of Spain, who had all but drowned himself in drink at the sorrow of the deaths of his mother, and younger brother, died of what must have been Cirrhosis at the age of fifty-two, after ruling over Spain for thirty-one years. He would join his family members that predeceased him, including his first wife Mary Tudor (María de Inglaterra) and their eldest son Juan, in being buried at the Alhambra.

His eldest surviving son would then become Alfonso XII of Spain, who, like his cousin, Arthur I of England, came to the throne with substantial experience from his time as heir to the throne, at twenty-nine years of age. Alfonso would ensure that little would initially change upon taking the throne, for while he occasionally had a difficult relationship with his late father, he retained most of those that his father had hired as ministers. Naturally his lover, Don Rafael Núñez would be one of the foremost poets in his court and was soon married to a noblewoman; Doña Antonia Enriquez de Toledo (b.1532, d.1590) a distant cousin of the King who, unlike Queen Jeanne, seemed aware of the relationship between their husbands. Fortunately for the two men, the young woman seemed indifferent to the affair, and kept it a secret. Ironically enough, the court would become even more staid in regards to courtly love, with King Alfonso XII demanding that his courtiers keep themselves outwardly chaste, and go to mass with him.

Shortly after taking the throne, King Alfonso would arrange a marriage for his second eldest daughter; the Infanta Catalina, for, while it was believed that Queen Jeanne may be able to bear a son, he wanted to ensure that Catalina, as second-in-line to the throne of Spain, was married to another scion of the dynasty. Thus, he decided that Catalina would be engaged to Ferdinand (Ferrandino) of Calabria, eldest son of his newly ascended cousin, Frederick (Federico) II of Naples, and Marguerite of France, who was roughly five years older than his prospective bride. As for the Princess of Asturias’s marriage, young Maria remained unpromised for a time, for, Alfonso wanted to see if he would have a son, and then plan his eldest daughter’s match accordingly.

Another death occurring within this timeframe would be that of King Henri III of Navarre, who had never remarried after his first wife’s death, apparently resigning himself to his Kingdom becoming one of several within Spain, with same rights and privileges that Castile and Aragon were entitled to.

The Dowager Queen Philiberta, who had a decent relationship with stepson, was well provided for in her widowhood, and would be allowed guardianship of her teenaged daughters, the Infantas Constanza and Ana, before they left Spain for their marriages in France and England respectively.

Portugal for its part would also see plenty of change for the ruling House de Aviz. Perhaps most importantly, the family of Manuel, Prince of Portugal and Catherine of England would rapidly expand in this half a decade. This would include the Infante’s João and Eduarte born just a year and a half apart; João being born on January 14th of 1551, while Eduarte entered the world on June 28th of 1552, with both having godparents in their paternal and maternal grandparents respectively. Fortunately, Catherine of England would have a reprieve of nearly three years before having her fifth child, Infante Henrique, named for her younger brother, on April 9th. Sadly, the infant would die of an intestinal disease within two months of his birth, on June 5th.

Doubly tragic for the Portuguese would be the passing of Miguel I of Portugal, barely a month after his grandson’s premature death. On the nineteenth day of July, 1555 the King, while leading mass with his wife Queen Catherine, suffered a heart attack, nearly dropping the crucifix that he carried. Though courtiers and the King’s doctor rushed forward to see if they could help the old man, they soon realized that they were too late, and that the zealous King Miguel was dead, having been King of Portugal for thirty-three years. His widow: Catherine, and their many children were devastated, and the elder Catherine of England, now Dowager Queen, was said to have worn black for every day of the rest of her long life.

The reign of King Manuel II, to some, seems to have signified a much more hedonistic court (hardly difficult in the dour Iberian Kingdom) than that of his father, due to his mistresses and illegitimate children, to whom he granted much favor. Even some of his officials openly kept mistresses and brought their bastard children to court, something which would have never been tolerated under King Miguel.

Indeed, by the time he took the throne Manuel II had already sired six children out of wedlock, all but one of whom were by his mistress; Teodora de Almeida (b.1522) his youngest children by Teodora were; the prematurely born Antonio (b.1549, d.1550), Joana (b.1549) and Isabella (b.1552) and it is likely that the birth of little Isabella was the true reason for the age gap between the Infantes Eduarte and Henrique; as it has been speculated that Catherine refused to sleep with him for at least a year. By two more mistresses, a pair of sisters; Aldonça (b.1530) and Violante da Gama (b.1537) he would have several more illegitimate children by 1555. By Aldonça he had; Vittoria and Pedro de Portugal born in 1553 and 1555 respectively. His only child by Violante (before she was married to a court official) was Iolanda de Portugal, born shortly before her cousin and half-brother Pedro.

Across the Pyrenees Mountains in France, much would also change, with the birth of more children for King Francis (Francois) and his Austrian Queen, Elisabeth of Austria as well as the arrival of the Spanish Dauphine.

The first of these to come to pass was the birth of two more children to the King and Queen. Firstly, on May 14th, at the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Queen Elisabeth of France went into labor for the seventh time. Fortunately, the thirty-year old and her child would survive the birth, and it would be revealed that she gave birth to a third son, named Antoine for her paternal uncle; Antoine of Austria. Two years later Queen Elisabeth would become pregnant again, but unfortunately in the fifth month of her pregnancy in September, she would deliver a stillborn son, which many (falsely) assumed would be her last child.

It would be one year after this unfortunate event that Constanza of Aragon, eldest daughter of the late King Ferdinand VI of Spain and Philiberta of Savoy, would arrive in France to wed the Dauphin Louis in 1553. Fortunately for Constanza (Known to her new people as

Constance d'Espagne) she would not initially face the same difficulties that her Austrian mother-in-law had experienced as Dauphine, for it seemed that this marriage would secure peace between France and Spain, though her considerable dowry no doubt played a role in how well she was accepted. Her husband, the fifteen-year-old Dauphin, seemed to dote on his older bride, and was, at least in the beginning of their marriage, faithful to her. The two were even somewhat similar in their coloring, as both were pale and blonde, inherited from their (Constanza’s) father and (Louis’s) mother, respectively. When it came to their personalities the two were also rather compatible. Constanza, like her mother, Philiberta was high-spirited, but unlike her parents she was of very humble demeanor. The Dauphin Louis for his part was dutifully religious, not as pious as his father but he was no unbeliever, while he inherited his Austrian mother’s charm and sharp sense of humor.

Preparations were also made in regard to Prince Charles, the King of France’s second son. The boy, like his father before him, had always been exceptionally pious and austere, thus, it was decided that he would one day enter the clergy. Of course, this could also have some political ramifications, for it was hinted that King Francis hoped that Charles may one day even become a Cardinal in the Church, possibly rejuvenating French influence in the Curia. Upon the death of King Henri II of Navarre in 1555, King Francis turned his attention to the issue of that Kingdom’s succession, quietly preparing his armies for the war that he would soon initiate in the coming years…

Prince Charles, the Duc d’Orleans and eldest of the King’s younger brothers would also be engaged in a flurry of activities, procreation being foremost among them. By Maria of Savoy, he would have three more children in these years; a long-awaited son named Phillipe, born on April 12th of 1551. Next would be a daughter named Louise, born on the first of July in the year 1552 and lastly, there was their penultimate child; a son named Louis, who was born on January 20th, and died the same day.