"

You must not talk to him about Zionism. That is a phantasmagoria. Jerusalem is as holy to these people as Mecca is."

Arminius Vámbéry, born Hermann Wamberger, had an Orthodox Jewish family history. Crippled at birth, he was on crutches when his mother sent him out to fend for himself at the age of twelve. As an apprentice to a tailor he won a scholarship to the St. George Gymnasium in Bratislava, discovering his phenomenal talents as a polyglot. After he had limped his way across the whole length of the Hapsburg realm, he had started a new life in Constantinople as a cabaret singer. Within the year, he had climbed from French tutor in the Sultan’s harem to secretary and adviser of Grand Vizier Fuad Pasha, befriending Sultan Abdülhamid II in the process. He had received a grant from the Hungarian Academy of Sciences to study the ancient history of the Magyar tribes, and spent three years roaming through Turkestan, Samarkand, Bokhara and Persia. His fame as an adventurer had made him an instant celebrity in Britain, and he met with Disraeli, Palmerston and Edward VII himself. By the end of the century he was working as a professor of Oriental Languages at the University of Budapest.

The old orientalist and traveller was fluent in twelve languages. He had changed religion like common men change their shirts - he been a Muslim as a young man in Constantinople, a Protestant as a Professor of Oriental Languages in the University of Budapest, and his father had been an Orthodox Jew. A personal friend of Sultan and King Edward VII and an expert of Central Asia, he had carried out several diplomatic missions and espionage for both the Ottoman and British governments. When Herzl met him he was as 70-year old atheist, a man who was no longer sure whether he was an Englishman or a Turk. Yet he genuinely wanted to help Herzl, and boasted that he could arrange a meeting with the Sultan.

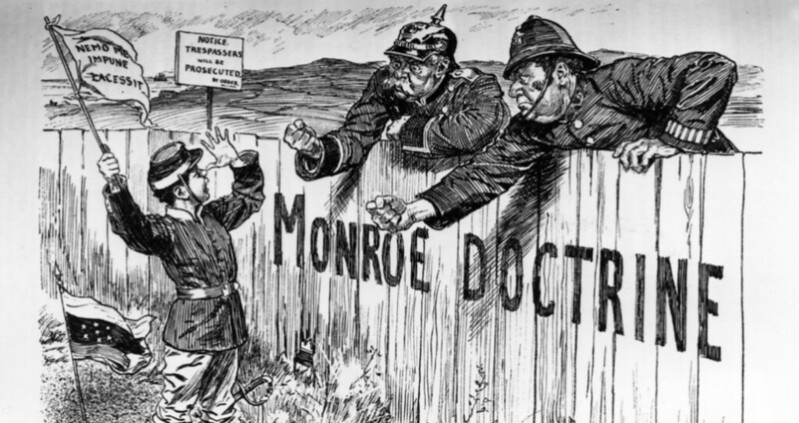

When he got in contact with the Hamidian administration Herzl soon discovered how clandestine and rottenly corrupt it was. He also found out that the fear of intervention of the Powers was the aspect that mostly frightened the Ottomans in the Zionist project. The logic was that influx of freely admitted Jewish immigration would be followed by military intervention of the Powers and loss of the Holy Land. Hence the local governor in Palestine was enforcing a strict policy that forbade foreigners to stay in the area longer than three months, with a complete ban on immigration.

To his own surprise, Herzl ultimately gained an audience with sizeable bribes and help from Vámbéry, and met Abdülhamid II in person.[

1]

For starters, Herzl thanked the Sultan for his benevolence towards the Jews - a rather factual statement, as the Ottoman Empire had been and still was wide open to Jewish refugees and they had a reliable reputation in the eyes of the Porte. During their cordial conversation, quoting the story of Androcles and the Lion, Herzl then offered his services to help the Sultan with the matter of Ottoman public debts. Abdülhamid II in turn gave Herzl the permission to make his pro-Jewish sentiments public, stating that what his realm needed most was the industrial skill of the Jewish people, promising “permanent protection” to those Jews who sought refuge in his lands.[

2] But aside from this PR stunt and a diamond pin offered as a gift and token of personal friendship, Herzl got little more from the regime of Abdülhamid. The Ottoman middlemen kept milking his movement for cash, while the viziers and pashas made a lot of promises and did nothing.

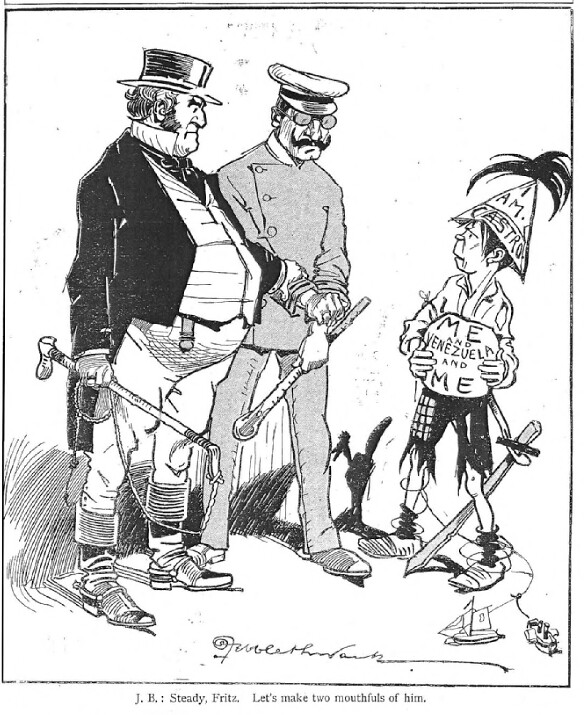

But while he was talking to the Ottomans and getting nowhere, Herzl was also pleased to find that the bombastic declaration and the following loss of interest from Wilhelm II had bought the Zionism a lot of international credibility and media attention. Just like the Ottomans had feared, the Jewish Question was now gaining attention the international media. In October 1902 Joseph Chamberlain, then acting as the British Colonial Secretary had met with Herzl, accepted his analysis of the Jewish question, and agreed with his proposed solution. El Arish, a largely empty region of the British-controlled, nominally Ottoman Khedivate of Egypt at the Mediterranean coast of Sinai Peninsula was considered for Jewish settlement despite Egyptian reservations of the endeavour. This plan caused bitter divisions within the Zionist movement as it was seen as betrayal of the goal of securing access to Palestine. For Herzl the negotiations were a valuable lesson for the complexities of Great Power politics around the issue. Yet the growing mass of Jewish refugees fleeing the persecution from Russia and Romania pressured the governments of Europe to act, and gave Herzl himself a sense of urgency to bring his grand plan to fruition at last.

He soon discovered that for the time being, the bitter hostility aroused by the Boer War, mutual press wars, and the Navy Bills had made true Anglo-German rapprochement seem impossible. Yet a German-British joint protectorate for Zionist Land Company, its financial institutions seated to London and political activities centered in Germany and Austria-Hungary was not something out of the realms of possibility. The British press had viewed the Near Eastern tour of Wilhelm rather favourably. And after he had visited Germany and discussed with Wilhelm II in 1899 (after his journey), Cecil Rhodes famously stated that "

Asiatic Turkey ought to be turned over to Germany, since England can not rule the whole world and needs a buffer area between herself and Russia."[

3] Thus the problem was neither in London or Berlin.

The final stop in his journey was personally the hardest. News of pogroms abhorred him, but Herzl saw no alternatives. He had to gain Russian approval to plans to allow the Russian Jews to emigrate to Palestine, and to lift the legal restrictions imposed on the Zionist Organization in Russia. He had courted Nicholas II and his key ministers for a personal audience since 1896 had so far been in vain, until Sipiagin, the Minister of Interiour received Herzl on 8th of August 1903. “

The Jewish Question is a vital question to us.” Sipiagin stated that until the Minsk conference he had been sympathetic towards the Zionist movement, but this new trend about talking Jewish nationalism, organization and culture - that wouldn’t do. Russia desired homogeneity of its population, but a massive assimilation of Jews was impractical. Thus the emigration was a logical answer. Herzl was eager to help, stating that the quicker he could reach land, the quicker the defection to the Socialists would end.

Sipiagin agreed on all proposals of Herzl. The Sultan was to be pressured "

with an effective intervention" in order to obtain a charter for the Jewish colonization of Palestine, the Russian government was willing to provide a financial subsidy for Jewish emigration, and facilities for the Russian Zionist societies to act in conformity with the Basle Programme. In August they met again, and Sipiagin stated that "

the creation of an independent Jewish state in Palestine, capable of absorbing several million Jews" suited the Russian Government best.

The same man who was busily

propagating the Protocols also had the gall to say that in its treatment of the Jewish question the Russian Government "

had never abandoned the accepted principles of morality and humanity”, and expressed hopes that as emigration would increase, the lot of the remaining Jews in Russia would improve. Herzl took this as a thinly-veiled threat.

The next step was meeting with Witte, a fierce competitor of Sipiagin. Satisfied with the promise that the Holy Places in Palestine would remain inviolable, Witte eventually agreed that the Zionist solution would be “

a good one, if it could be carried out”, and promised to lift the restrictions on the financial activities of the Jewish Colonial Trust.

Herzl followed up by approaching Count Muraviev. But to reach him, he had to wade through the Russian court politics. the Jerusalem Declaration and following rumours made Russians mistrust all German political initiatives in the Orient. Muraviev was adamant in the Russian interests towards the Holy Places in Palestine. The Imperial Russian Palestine Society took great pains to extend its influence, organizing pilgrimages, maintaining missionary schools, erecting churches and acquiring landed property in the region. Herzl thus begun by appealing to General Kireyev, the

aide-de-camp of Nicholas II. Having met him before, he managed to convince Kireyev to introduce him to Nikolas de Hartwig, head of the Asiatic Department and President of the Imperial Palestine Society. Hartwig, like Sipiagin, told Herzl that his cause was favored by Petchovski Most. By December 1903 Sipiagin informed Herzl that Count Muraviev had agreed to inform the Sublime Porte that the Russian Government viewed the Zionist project of resettlement of Jews in Palestine favourably, and that a friendly response from the Porte to the Zionist request would attest to the “

bond of friendship that exists between the two empires.”

In the final document that Sipiagin drafted with the approval of Nicholas II the absence of any mention of Sultan’s sovereignty, specifically mentioned by Herzl, and the emphasis on an “

independent state” reflected the general line of Russian policy. The document clearly aimed at dismemberment of the Ottoman Empire, while it also sought to gain Russia international clout as a champion of religious minorities living under the “Turkic Yoke”. As an immediate measure the Russian Government levied an extra tax on the Jews to facilitate the work of the emigration societies and providing their needs - how much of these funds actually reached the societies themselves was another matter. They also gave protection to the Zionist emissaries at Ottoman territories.[

4]

Internationally Sipiagin’s letter served as a key to the Great Power diplomacy for Herzl. He finally met with his own Government authorities at the highest level, when von Goluchowski granted him an audience. A strong critic of anti-Semitism in the Dual Monarchy, he felt that Herzl’s project was so praiseworthy that every government should support it financially. He furthermore stated to Herzl that no petty or half-way measures would do - asking the Ottoman Empire for land and legal rights for 5-6 million Jews was the only way to stir the Great Powers into action!

Despite of his strong support, Goluchowski was unwilling to bring Vienna forward as the leading Power in the initiative - the relations with the Porte were too critical for that. It would be better if Britain took the lead - and Herzl should also secure support from Budapest first, especially from Count Tisza. This reluctance rose from the desire to maintain the secret agreement with St. Petersburg about keeping “Balkans on ice”, and avoiding moves that would unilaterally disturb the status quo. Here Goluchowski was already contemplating the future of the Balkans, and the idea of a Jewish Palestine was only part of a larger puzzle, where the hope of reviving the 1887 tripartite Mediterranean Agreement loomed large.[

5]

With the Sipiagin Letter Herzl could finally court France, strating by letters to her foreign office representatives and the Ambassador at Vienna, stating that since her Russian ally had already de facto renounced any claims to Palestine, French motives for further protests on religious grounds would no longer be credible. With the Combes Cabinet working with a Chamber that was Republican, Radical and Socialist in majority, the pressure to act jointly with Russia in Palestine gained new urgency as the questions of the future of Suez, Egypt and Lebanon were raised in the French colonial lobby. Herzl was thus able to tour Paris on his way to Rome, meeting with representatives of the French government and receiving assurances that the Dreyfusards were now firmly at the helm - and that France had to be included to any potential arrangement involving Palestine.[

6]

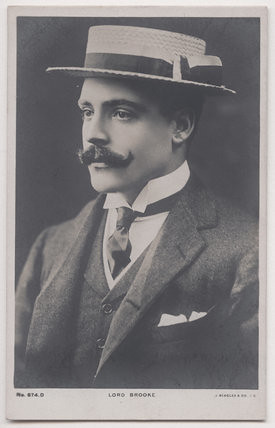

Herzl met further success in Rome in January 1904. King Umberto I proudly stated that his realm had no racial discrimination: Jews held posts in the Diplomatic Service, and almost every government included a Jew. Italy thus had no Jewish problem, but Zionism still had its positive attractions. Palestine “

will and must get into your hands”, the King told Herzl. "

It is only a question of time. Wait until you have half a million Jews there!” Tommaso Tittoni, the Foreign Minister of Italy, wanted to avoid any reneval of Austro-Russian constellations at the expense of Italy, and promised to proceed jointly with the Russians in this issue. Meanwhile the Vatican remained defiant.

Anyone who denied the divine nature of Christ could not be given possession of the Holy Land without giving up the highest Christian principles...Gerusalemme must not get into the hands of the Jews.”[

7]

Back in Germany Wilhelm II wanted to stay true to his self-proclaimed role as a friend of the Sublime Porte, and stated strongly that Germany had no wish to see the Ottoman Empire lose control of Palestine because of this endeavour. This was not inconsistent with Herzl’s ambition, as charter for a Jewish Colonization Company guaranteed by the European Powers was all he was after.

And with Britain willing to benevolently watch from the sidelines and lend a hand at El Arish, Herzl stated to Eulenburg, the new Chancellor, that he “

would gladly let Wilhelm II have the glory of placing himself at the head” of the Concert of Powers on the Zionist question. And just when the international diplomacy seemed to be aligning towards a potential solution, ARF Demonstrative Body assassinated Abdülhamid II on Friday, 21st of July 1905. The matter was however a joint topic of discussion, and the "spirit of Rome" that resulted to the implementation of the Mandelstam Plan had a lot to do with the fact that the Powers had a single topic where they were more or less in general agreement. Lifting the ban of Jewish settlement in Palestine was thus part of the August Ultimatum the Powers jointly represented to the Porte in 1905.

1. As per OTL

2. As per OTL - note that Abdülhamid II made no promises to stop the immigration restrictions to Palestine.

3. As per OTL

4. In OTL it was Plehve who championed the Zionist solution to Nicholas II. Sipiagin, who holds the post Plehve had in OTL, is just as eager to promote a program that can be used to advance his own anti-Semitic foreign policy goals. The tax was discussed as a possible measure in OTL as well.

5. As per OTL

6. Herzl never travelled to France in OTL. Here the success with Wilhelm II encourages him to overcome his prejudices and approach the French authorities - much to his surprise the domestic politics of France turn the matter into a point of policy, and France is willing to go ahead due her extensive economic involvement to the Ottoman finances.

7. As per OTL - with the difference that Umberto I is alive and well