"

I just recently learned this, but believe it or not, those two interviews happened on the same day. Of course, the piece in George didn't run for another couple of weeks, but if you want to try and trace it back--where things started to really shift--there you go. I mean, the Imus thing was all anyone was talking about that Thanksgiving. Before the Imus interview, everybody thought Trump was a joke. After the interview, all the people who thought they were smart--myself included--still thought he was a joke. But really, he was a phenomenon. And the whole Arpaio saga, that piece was the genesis of it all. I mean, Dougherty had been covering Arpaio for years, and eventually he was the one who ended up taking him down. But that piece was how Dougherty and Kennedy hooked up. So yeah, Imus and Kennedy, strange as it may seem , are kind of the ones who helped turn the Reform Party into a prairie-fire."

-----Anderson Cooper, 2017, in

Burned: the Rise, Fall, and Undeath of the Reform Party, by Matt Taibbi

November 19th, 1999

* * * *

When November began, John had no intention of interviewing Joe Arpaio on the Tuesday before Thanksgiving. Until that Friday, in fact, John had no intention of interviewing Joe Arpaio at all.

On Friday the 19th, John was eating lunch with Richard Blow, one of the staff writers at

George, and thinking of the infinite dread with which he contemplated joining the extended Kennedy clan for the holiday week. It wasn’t just the typical anxieties one might expect from a recent widower at a big family gathering that preyed on his mind. Most recent widowers didn’t have to deal with the prospect of paparazzi hiding in the oyster stuffing, and most recent widowers weren’t getting anonymous death threats mailed to their offices every week.

The death threats began about a month after John returned from Camp David. It started when some jackasses on talk radio started claiming that the plane had gone down on the thirtieth anniversary of Chappaquiddick. It

hadn’t gone down on the anniversary--and John wasn’t sure what it would prove if it had--but the truth had never gotten in the way of people believing nefarious things about the Kennedys. Soon after, a minor talk radio personality named Ken Hamblin questioned whether Carolyn had actually been in the plane at all. He didn’t answer his question--he didn't need to. The callers provided the theories and accusations. All Hamblin had to do was provide the innuendo. After that, it was only a matter of time before the most marginal of John and Carolyn’s hangers-on were slipping salacious items about the state of his marriage to the tabloids, including

The National Enquirer--now run by David Pecker, his old boss at Hachette. Beginning with the “revelation” that John was living alone in the Stanhope Hotel in the months before the crash, a slow, steady drip of embarrassing details about the breakdown of his marriage leaked to the press. Every shitty detail leaked to a tabloid seemed to fertilize the corresponding fever-swamp of conspiratorial innuendo in talk radio circles. A couple weeks back, Bob Grant, the Tri-State area’s answer to Rush Limbaugh, had a supposed expert on his show who claimed that it was “impossible” that Carolyn’s body could have been swept to sea.

The mainstream media wouldn’t touch the story--at least not directly. But the same companies that owned CBS and NBC News also owned

Inside Edition and

Entertainment Tonight. Although the

Inside Editions of the world weren’t reporting on all the conspiracy crap that was floating around on talk radio, they scarfed up every succulent morsel of gossip they could, often hinting that John was a more controversial figure than they were letting on.

Case in point: earlier in the week, Deborah Norville called

him the “beleaguered heir to the Kennedy Dynasty” in response to a story that

Carolyn had used cocaine.

It wasn’t helping matters that John had not publicly spoken to the media at all since the memorial, and that he hadn’t done anything in-depth since the crash itself. Not that he hadn’t had opportunities. Barbara Walters, in her own very polite way, was becoming a huge pain in his ass with the weekly requests for a long sit-down.

“Just you and me. Minimal crew,” she’d said in her last request. Just John, Barbara, “minimal crew,” and about 200 million viewers was a better way to put it. Truthfully, John couldn’t be bothered. With the impending buyout, his slowly mending body, and his interview with Castro in January, he just didn’t have the energy to attend to his public image. SI Newhouse, for example, had insisted on no less than

four separate meetings with John before he agreed to basically the same deal as the one John and Florio had worked out. He was doing physical therapy three times a week, and the doctors were now telling him he might always walk with a limp, even with the therapy. In addition to the mountains of background he was doing on Castro, he’d hired a tutor to help him brush up on his Spanish, on the off-chance that John might catch something the interpreter translated too generously. All of this was in addition to the normal duties he had as Editor-in-Chief. With all of that, he didn’t even have the energy to

have a public image, much less cultivate one.

The advent of the death threats was another incentive for him to lower his profile. He told himself that if he starved the media, the crazies would eventually go away. He wasn’t sure whether or not he was just telling himself what he wanted to hear, but he knew that his grief and stress weren’t going to let him act any differently. So he tried not to think too hard on whether or not he was being truthful with himself. It just seemed like a dead end.

The latest death threat was a doozy. It was illustrated with pictures of the fight John and Carolyn had right after they’d been engaged--pictures that had run years ago in

People magazine--and lettered with cutouts from previous issues of

George. As John was preoccupied with the pictures, Richard had noticed that particular detail himself.

“Do you think it’s a subscriber?” asked Richard.

“That would be one reason someone would have multiple issues of

George,” said John, his inner lawyer kicking in. Try as he may, he wasn’t entirely sure what the other reasons would be. “The overlap between

George subscribers and people who think I killed my wife has gotta be pretty small though. Right?”

Richard, who was an ivy league Ken-doll in the form of a journalist--no obvious flaws, no obvious problems, no obvious personality--looked down at his chopped salad awkwardly. The death threats seemed to throw him off balance even more than they did John. “Where’s the postmark saying it’s from?”

“Huh,” said John. “Good question. Phoenix--let’s get a list of Phoenix subs.”

“Oh, sure. What’s that going to tell you though?”

“Not going to tell

me anything.” John pushed away the take-out container. “Might tell the Phoenix police who’s sending me death threats, though.”

Richard caught the hint, and began to clear his own place setting. “You’ll want the sheriff though. In case they’re outside city limits.”

“Sure,” said John, who was still staring at the pictures pasted on the death threat. He kept coming back to the one where he had tried to yank the engagement ring off Carolyn’s finger. That had left a bruise. “Just let Rosemarie know about the subscriber thing on your way out.”

Richard stopped short at the door. “Wait. Have you heard about this thing with the Phoenix Sheriff?”

“Isn’t he the pink underwear guy? The tent guy?”

“No,” said Richard. “I mean yes--he is that guy, but that’s not what I’m talking about. Have you heard about the assassination attempt?”

“

Assassination attempt? What?”

“That’s not even the best part, John. There’s a paper down there, a weekly called

The New Times, they’re saying he set the whole thing up.”

“Where was I when this--nevermind--

when did this happen?" John asked.

“Well, the story got forwarded to me right around the time you left the hospital.” Richard scratched at his chin as he tried to remember. “Mid-August? Something like that. I think the attempt happened in July. It’s wild. I don’t know why no one’s covering it.”

“Rich, we’re the press. Why aren’t

you covering it?”

Richard shrugged and kept his mouth shut, but the expression on his face read something like “

because of the fucking crash, man.”

John slumped in his chair. “Just go ahead and forward me the story when you get back to your desk.”

* * * *

As it turned out, the story was everything Richard claimed.

James Saville, a somewhat feebleminded 18 year old high school dropout, had been jailed for vandalizing and attempting to burn down his old high school in 1998. He’d been sentenced to 18 months, a sentence which he’d served without any serious problems. The trouble came when he made the acquaintance of a criminal informant and jailhouse snitch--given a pseudonym in the article--who managed to spin Saville’s idle boasts to get even with the prosecutor into an assassination plot against Sheriff Arpaio. While Saville was incarcerated, the snitch, who’d been working with the Sheriff’s Department, not only gave Saville the idea for the crime, he told him that if he did it, there would be--

Christ--parades in his honor. The snitch

also put him in touch with an undercover deputy who he claimed was a mob hitman. A mob hitman, who--coincidentally--wanted to pay Saville to commit the very crime the snitch had been telling him to commit. Within hours of release, the undercover had met with Saville, taken him to various hardware stores where the deputy bought the bomb-making materials, had him assemble the bomb, and then, once he had done, arrested him with news cameras rolling.

John did not love the law, as many lawyers did, and there wasn’t a day that went by that he wasn’t happy that he’d left the miserable profession. But he was still a trained lawyer with years of experience in criminal law; he’d won numerous convictions. And as a lawyer, he could say that this stunk of entrapment. It wasn’t just that the defense attorney was making a case for entrapment and presenting it well to the media. It was more than that. Not only was the defense claiming entrapment, the publicly available facts and the department's own statements supported it. James Saville was a nonviolent offender, given the idea for and the means to commit murder by the department itself. They’d created a crime where there was none, for the apparent purposes of raising the Sheriff’s public profile. In other words, Arpaio was incarcerating and indicting a teenager for a murder plot that Arpaio himself had cooked up, all so it could make him famous.

So Joe Arpaio could be a fucking celebrity.

Politics and celebrity. That’s what

George was supposed to be about, wasn’t it?

* * * *

“John Dougherty? This is John Kennedy, from

George magazine. Got a minute?”

“Is this--”

“No joke. I’m calling from Manhattan. Check the area code on your caller ID, if you’ve got it. You free?”

“Uh...

yeah. What’s up?”

“Just read your article about the whole Saville-Arpaio assassination fiasco. It’s good work. How long have you been covering him?”

“Oh,

Arpaio…” said Dougherty as if it were all starting to make sense. “Yeah, thanks...Been covering him since he was elected, more or less. He was elected in ‘92. I started at the

New Times in early ‘93. So me and Joe go way back.”

“You’ve done a lot of investigative work?” asked John.

Dougherty chuckled. “Little bit. Broke the Keating Five story back when I was in Dayton. Got the Governor arrested a couple years ago. Took me ten years, but I got him. Why do you ask?”

“Because I want to run it. I’d like to run the story.”

“I see,” said Dougherty.

It wasn’t the response John had hoped for. “Problem?”

“I just, ah, didn’t think you guys did stories like that.”

“Investigative stuff? We usually don’t. But we’re reorienting our focus a little. Still politics and celebrity--but from what I can tell, this guy wants to be a celebrity more than any local politician in the country. And

Rudy Giuliani is the mayor of my hometown, so it’s not like he’s got no competition. You know, you’d have to rework it a little bit--it’s got no national context--but we can credit

The New Times on the reporting. You interested?”

Dougherty hesitated. “Well, I guess my question is--if you’re crediting us for the reporting, what does

George bring to the piece?”

“Good question.” It was John’s turn to chuckle. “So, long story short: it looks like someone from Phoenix is sending me death threats. I talked to Sheriff Joe about it this afternoon--

very accommodating--and while we got to talking, I told him I was going to be in Phoenix early this week. He agreed to give me a tour of the jail and sit down with me for a couple of hours on Tuesday. Correct me if I’m wrong, but I’ll bet he won’t talk to you for shit.”

“Hates me,” said Dougherty.

“And I’ll bet you’ve got some questions you’d like to ask him.”

“No shit?”

“No shit,” said John. Silence on the other line. “You in?”

“Hell yeah I’m in,” said Dougherty. “

This Tuesday? Two days before Thanksgiving?”

“Yeah, but I fly in on Monday. Meet me at my hotel, brief me on Monday night. It’ll be fresh when I talk to Joe.”

Maybe Thanksgiving wasn't going to be such a drag after all.

* * * *

KENNEDY/ARPAIO INTERVIEW

TRANSCRIPT OF TAPE 2

NOVEMBER 23, 1999

KENNEDY: So you were wrongfully accused of murder, is that right?

ARPAIO: Excuse me?

KENNEDY: In Turkey, back when you were a DEA agent. I’ve got a quote from you--

ARPAIO: Oh, Turkey. Yeah. That’s a different story.

KENNEDY: A

different story? You’ve only been arrested for murder once, right?

ARPAIO: Oh, of course, just the once. [

laughs ] It was several decades ago. I don’t need to play Wyatt Earp anymore. Still could though--I haven’t lost a

step.

KENNEDY: You were incarcerated for that?

ARPAIO: Briefly. You know, it was me and four other guys--four other agents--and we got into a gun battle with some dope-pushers--

KENNEDY: And you saw a lot of action over there?

ARPAIO: Oh, it was a hot zone. A real hot zone. You seen

The French Connection? That movie was about what

we were doing. They based that character--Popeye Doyle, the one Gene Hackman played--partly on me, you know. I’ve got more hair though. [

laughs ]

KENNEDY: Yeah, you’ve got more of a John Wayne thing happening. Anyway, a lot of action. “Weekly gun battles,” is the quote I’ve got here.

ARPAIO: Well, I don’t know that uh, that was a

direct quote.

KENNEDY: Misquote?

ARPAIO: Exactly.

KENNEDY: It came from the transcript from when you testified before Congress. So anyway, who were the deceased?

ARPAIO: Who? Oh--the deceased. He was just some dope peddler. Dime a dozen, really. I mean, there were more than one that probably took bullets from me. I never killed nobody in the United States though.

KENNEDY: You said there were two, back in ‘89. You don’t remember their names?

ARPAIO: It was a long time ago. I can’t remember every little detail--

KENNEDY: But you shot them.

ARPAIO: --about every scumbag I’ve taken down. I’m not losing a bit of sleep about it. I’ve had a long career. Things happen. Shot him? Yeah. I was the only one with a gun.

KENNEDY: In

the gun battle... And you can’t remember who they were? We wanted to do a little background on them. Give the readers some context, so they know the kind of dangers you were dealing with. Anyway, what was it like in Turkish jail? You ever seen

The Midnight Express?

ARPAIO: [

Laughs ] They actually treated me pretty good. You know, I was an American, and I was with the DEA. They knew they had to be decent.

KENNEDY: And it’s an inquisitorial system over there, so I was thinking it might have been pretty rough. Anyway, you’ve got a reputation as being tough-on-crime. You’ve got the tent city, you’ve re-introduced chain gangs, you’ve taken away the tv, the salt-and-pepper from the cafeteria. What’s the philosophy behind all this?

ARPAIO: Don’t forget about the coffee. Saved a hundred and something thousand a year on that.

You pay for your coffee,

I pay for my coffee. Why should criminals get free coffee? The philosophy? You can’t coddle criminals, is the philosophy! Jail’s not supposed to be the Holiday Inn. It should be a humiliating experience. I

believe in humiliation. I want to make jail the worst place in the world, so they know not to come back for a visit. People talk about prisoner’s rights--but the fact is, what I hear from the public over and over again is that prisoners should have

no rights. Deterrence is the name of the game, and if I’ve gotta make it as bad as a concentration camp to achieve that, that’s what we’re going to do to protect the people of Arizona from these animals.

KENNEDY: But a lot of people in jail haven’t been convicted of anything. A lot of them will be, but a lot of your inmates are awaiting trial, right? Three-quarters, right? You were wrongfully accused yourself--

ARPAIO: You can’t compare me to the convicts. Period. Apples to oranges.

KENNEDY: But I’m talking about the ones who aren’t convicts--

ARPAIO: Next question.

KENNEDY: Okay. I’ve got a case here. Felix Bordallo Ruiz. Arrested on 7-7-97 on suspicion of DUI. Bordallo claimed that he was on a new medication. He was field sobriety tested and arrested, never given a breathalyzer. He was awaiting trial for 73 days. In that time, he lost his job, was evicted from his apartment, and his car was repossessed. Turns out, he was on the medication, not drunk. Charges dismissed. Did Felix deserve a concentration camp?

ARPAIO: There’s always going to be isolated exceptions. What we’re trying to do is create a culture. It’s about hard knocks. Tough love. And making sure that the criminal element is not welcome in Maricopa County.

KENNEDY: Isolated? I’ve got quite a few of these. There’s Scott Norberg--died in detention after your deputies, what, asphyxiated him with a towel? Tough love?

ARPAIO: Those deputies did

nothing wrong! They followed

the policy, is what they did. It was a freak accident. Norberg was resisting! The Norberg case was--

KENNEDY: Norberg was handcuffed to a chair. How much resistance was he putting up?

ARPAIO: The Norberg case was an accident, and we’ve already changed policies to make sure it doesn’t happen again. Sounds like you’re talking to the enemy, frankly. Crime is down! You want evidence that the policies are working, look at that. Crime is down under my tenure--way down. End of story.

KENNEDY: But crime is down

everywhere. And I’m glad you brought this up. Crime

overall is down in Phoenix. But the murder rate is way up. Phoenix and Baltimore are the only two metros in the country that didn’t see a drop in the murder rate in the past decade. Baltimore’s is pretty much where it was ten years ago--but Phoenix’s increased from 14 per hundred thousand to over 16 per hundred thousand. How do you account for that?

ARPAIO: We’re not the only law enforcement agency in the metro, you know--

KENNEDY: But you’re the highest ranking law enforcement officer in the county. Doesn’t the buck stop with you?

ARPAIO: --there’s the Phoenix Police. Now there’s an agency you need to look--

KENNEDY: How did hiring James Saville to build a bomb--to kill you--a few hours after his release further deterrence?

ARPAIO: Saville? I can’t comment on an ongoing investigation, and I’m sure you know it. What the hell kind of interview is this supposed to be?

KENNEDY: Just a question. With the spike in the murder rate, how does the department have the time to concoct their own murder plots?

ARPAIO: This is over.

This is bullshit. This interview is done. [ Storms Out ]

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

IMUS/TRUMP INTERVIEW

TRANSCRIPT, PART 2 OF 3

IMUS IN THE MORNING

NOVEMBER 23, 1999

TRUMP: You know I like women, Don. I’m a man, so I like women--you should see my girlfriend Melania. Trump likes women, okay? No problems in that department. But you know, the way I look at Clinton--I see a man who’s weak minded. Very weak minded. It’s not like he’s picking the quality, okay?

IMUS: Ooooh, no. Definitely not picking the quality. Woof.

TRUMP: Right? You look at these women--and you know, at first I didn’t even believe it, cause he’s the Governor, right? He’s the President, right? And you should see these women, Don. Paula

Jones? When I first heard it, and then I saw her, I said “that can’t be right.” And I look at it, and you’ve got Lewinsky, and I think he’s a very sick man. I’m not sure he can help himself. He’s like an animal or something, Don.

IMUS: Woof woof. So you think he’s got problems?

TRUMP: It’s sad--sad. When you think about it, you know, he’s got a lot of problems with self-control. And he had a chance to do some things, you know. A lot of people don’t realize, but Clinton had a chance to do a lot of things. Because the President, you know, is really more powerful than most people imagine. And he wasted it.

IMUS: For a plump co-ed--

TRUMP: A little too plump.

IMUS: --and an Arkansaw Lot Lizard!

TRUMP: And maybe that’s why Hillary--you know, she’s had to put up with a lot, very troubled marriage--you know, maybe that’s why she’s such a nasty woman sometimes. Who knows? It’s sad. Sad for the country, really. Sad for the families. And they’re laughing at us--all the other countries--they’re laughing.

IMUS: So we’ve got Clinton the sex-maniac for the Dems--

TRUMP: I never called him that. [

laughs] Imus is trying to get me in trouble.

IMUS: Would you leave

your daughters alone with him?

TRUMP: Ivanka? No way. He wouldn’t be able to control himself.

IMUS: So, Clinton for the Dems. What are your thoughts on the Republicans?

TRUMP: Well, you know, some of them you can barely even remember. But I guess you’ve got the main ones. There’s Bush, and with him, you wonder if the guy’s really all there. I mean, you’ve got that book, about the monkey,

Curious George, and really with Bush, it’s like a not-so-curious George. I mean, you know, that’s what the people are saying. And you know, Bush--the original Bush, not Junior--he’s a real New World Order kind of guy. That’s his thing. And so I guess that Junior’s probably the same. And who else is there?

IMUS: You’ve got Forbes--

TRUMP: Oh, Forbes. Well--and he’s kind of a smart guy, thinks he’s a real smart guy--and well, you know, the thing is with Forbes, his father was a real

flamboyant kind of character. You just wonder with Forbes, is he really the kind of guy you want sitting across from Khrushchev? You need a leader in the White House, really. You need leadership.

IMUS: And then there’s McCain.

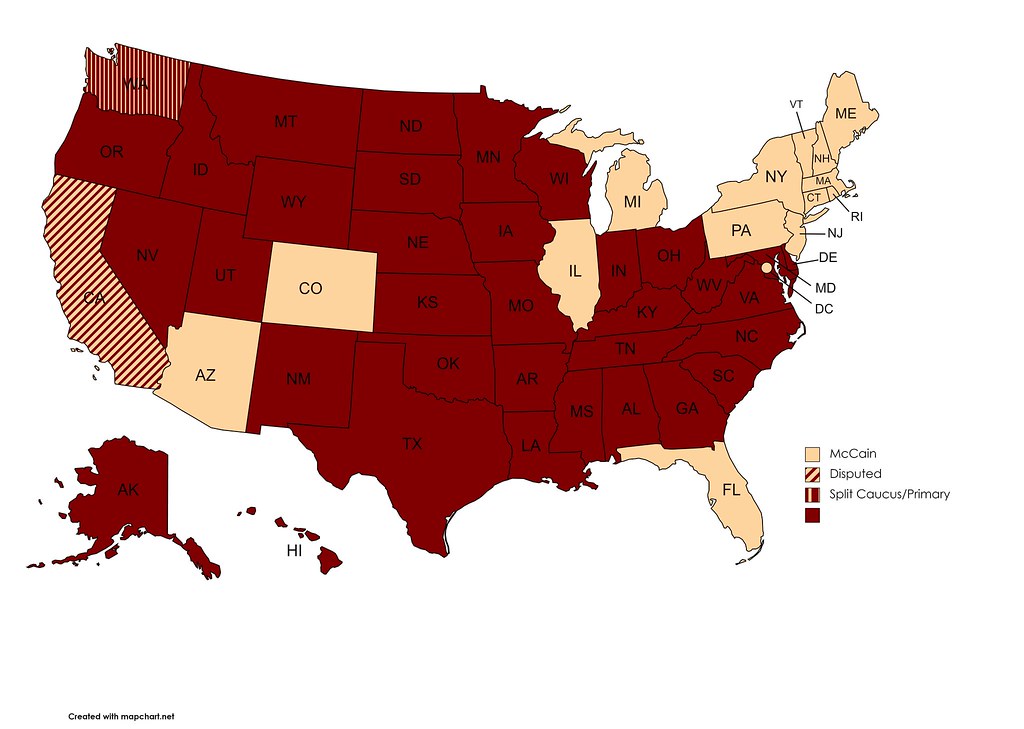

TRUMP: And McCain, you know, there’s a guy I really feel sorry for. Because--and he was some kind of war hero, you know--they’re never going to let him win.

IMUS: So you’re saying it’s rigged against him?

TRUMP: You think I don’t know? Rigged--these guys

all come to me. Democrats, Republicans. All got their hands out. You think if I put in a call these guys don’t take it? They’re begging to take my calls. I know how it works--and I tell you now Don, they’re never going to let McCain win. McCain’s onto them. He knows about the corruption. I think a guy like that, a year or two, and he’s going to be looking really hard at the Reform Party, because he’s going to see. He’s going to see that the New World Order guys are never going to let a guy like him get anywhere. And he’s going to have to take a hard look at it.

IMUS: Would you consider him for VP?

TRUMP: Only if you and Oprah turn me down, Don.

IMUS: You heard it here first, folks. “John McCain on Trump’s VP shortlist.” It is 8:26 a.m. here in the studio, that’s thirty-four minutes till the hour,

Imus in the Morning.