The Revolutions in Germany and Russia

The First World War came to an end with the outbreak of the German Revolution in 1918. Starved and demoralised by the Entente blockade the German people had had enough of war. Naval mutinies, first at Wilhelmshaven then Kiel, inspired revolutionary councils to appear across the German Empire. A republic was declared, and soon Emperor Wilhelm II and all of his subject monarchs abdicated; the provisional government immediately signed an armistice with the Entente. The Social Democrats, split between (‘Independent’/USPD) left and (‘Majority’/MSPD) right factions, struggled to maintain a semblance of order over a country going through the throes of social revolution. Inspired by the continuing success of the Bolsheviks (VKP(b)) in Russia the Spartacist League, a group of Independent Social Democrats, split from the party and founded a new Communist Party (KPD). The new party narrowly decided to participate in the federal elections of February 1919 and came in a close second behind the Majority Social Democrats. Leading the left-wing opposition to the increasingly rightward shifting Social Democrats, the Communists secured a majority of the seats at the next Congress of the Worker’s and Soldiers’ Councils in April. The Communists judged that the time was right to escalate the revolution and, in conjunction with the Independent Social Democrats and other socialist organisations, organised a general strike for May Day. The strike led to the beginning of the German Civil War.

The Majority Social Democrat-led government ordered the army and right-wing militias to suppress the strike. However many soldiers simply refused to fire on the strikers, while some even joined them. In Berlin street battles between loyalist soldiers and the revolutionaries carried on for five days until the latter’s victory, during which time the government had fled to the west. Early disunity in the counter-revolutionary movement allowed the socialist forces to capture industrial areas of the Rhineland and central and eastern Germany. This turn of events forced the Entente, who were already involved in the Russian Civil War, to intervene in Germany as well. The two civil wars essentially merged into one conflict as both socialist states were fighting the same enemies. Socialist revolutions in Poland, Hungary, and Slovakia were also successful due to the arrival of Russo-German forces, while Franco-British aid to the German counter-revolutionaries pushed socialist troops out of Baden-Württemberg and the left bank of the Rhine. The German Civil War ended with a ceasefire in November 1920. The Bolsheviks had won their war by mid-1923 though similarly to Germany they had failed to maintain control over the territorial extent of the preceding empire; due to the push through Central Europe anti-communist forces had been victorious in Finland, the Baltic, and parts of the Caucasus and Central Asia. The stage was set for a second great conflict, though this time between the socialist world and the counter-revolutionary world.

The Interwar Period

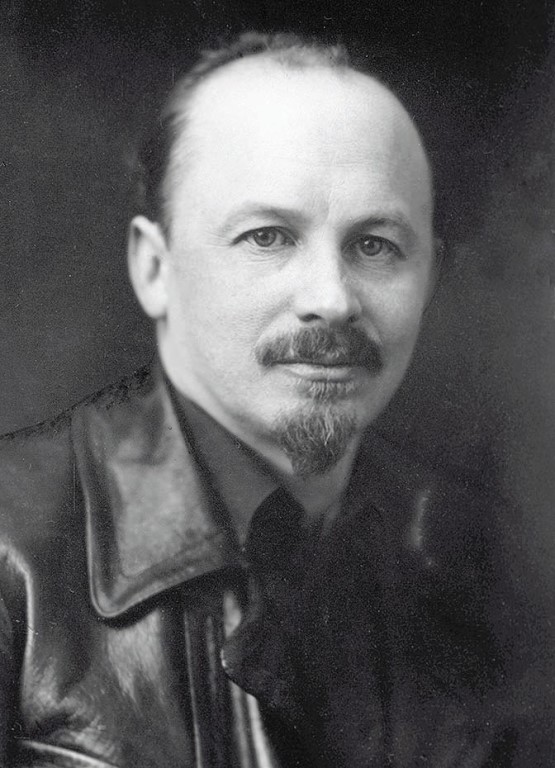

The Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and the Free Socialist Republic of Germany were both founded on the principle of workers’ council-based democracy. In the USSR however, the long civil war and the difficulties it produced were too much for the council (soviet)-based state apparatus to handle. As a result, the Communist Party leadership gradually took control of the government in order to effectively prosecute the war and govern the country. Following the war the party’s leader, Vladimir Lenin, recognised the danger of the new Union becoming an overly bureaucratic party-state, but his illness and factionalism within the party prevented any meaningful reform. Upon Lenin’s death in 1927, Lev Kamenev succeeded him and sought to restore the power of the soviets in alliance with Nikolai Bukharin. Kamenev was soon outmanoeuvered though by Bukharin, who received most of the credit for the reinvigoration of the soviets. By the beginning of the Second World War, Bukharin had become secure in his place as the unofficial leader of the Soviet Union. On the other hand, the relatively short civil war in Germany forestalled a fate similar to that of the councils in the Soviet Union; they maintained their democratic character and alongside the Communists, the U/VSPD and the anarchist Free Workers’ Union of Germany (FAUD) participated in the council government. Rosa Luxemburg served as the Chairwoman of the Congress of Ministers from the birth of the new Germany until well into the 1930s, when she resigned due to illness. She was succeeded by Wilhelm Pieck, who had earlier played a key role in establishing International Red Aid.

The interwar period resulted in a significant weakening of the counter-revolutionary bloc with the Great Depression acting as a catalyst for many of the upcoming conflicts. Civil wars in Portugal, Italy, and Spain led to socialists gaining power in the former two countries, while the colonial empires of all three suffered dislocation and anti-colonial dissent. The other European liberal democracies became increasingly authoritarian, weakening the power of the left through both legal and non-legal means while simultaneously tightening their control of the colonies. Such heavy-handed tactics led to a republican revolution in Sweden in 1920. Though the country remained a neutral liberal democracy, it was governed by a broad left coalition that included the Social Democrats and the Communists. Colonial rebellions, often aided by agents from the Communist (or Third) International, kept the western powers occupied while the Comintern member states rebuilt themselves following their civil wars. The breakdown of authority in British India is perhaps the most emblematic event of the end of the old colonial world order; socialists, nationalists, and princely states all battled each other and the British authorities as they tried to achieve their various territorial and ideological aims. During this period, the Comintern had also agreed to limited cooperation with the reformist and revolutionary socialist parties of the non-communist International Working Union of Socialist Parties, the so-called 2½ International.

Seeing the madness engulfing Europe, the United States of America turned their back and elected a series of isolationist Republican presidents: Hiram Johnson, Calvin Coolidge, and Herbert Hoover. While the United States ignored Europe they intervened regularly in Latin America, supporting friendly governments and ensuring a steady supply of raw resources for American industry. This policy agenda protected the country from the effects of the London Stock Market Crash in 1929, yet it was only a harbinger of things to come. The New York Stock Market Crash months before the election of 1932 ruined the already-stagnating economy. Democratic candidate Henry Ford won the election on his campaign of austerity, business modernisation, and continued isolation. Even though the rights of trade unions and workers were curtailed, the economy stabilised just enough to secure Ford’s re-election in 1936. Across the Atlantic, Britain was beset with terminal instability. The failure of the interventions in mainland Europe and an uneasy peace after the Irish War of Independence resulted in a loss of confidence in the Liberal-Conservative coalition government. The subsequent general election of 1922 led to an unstable coalition between Labour and the other faction of the divided Liberals under Prime Minister Herbert H. Asquith. The government struggled internally for a year until Labour finally withdrew its support and precipitated another election. The Conservatives gained a majority and embarked upon a protectionist trade policy, prompting the Liberals to unite in the name of free trade. The general strike of 1926 caused more problems for the Labour party than the government; the Labour leadership denounced the strike as revolutionary, causing the growing rift between the moderates and the Independent Labour faction to solidify. The failure of the economy to truly recover however produced a hung parliament at the election of 1928, while Labour had officially fractured into two parties. Once again the Liberals formed a coalition with (the mainstream faction of) Labour, but only a year into their government the London Stock Market Crash jettisoned any hopes of an economic recovery. The government floundered on until the next election in 1933, where the Conservatives received a healthy majority. Their solution, as ever, was more protectionism and more austerity.