Chapter 48: The Battle of Greece:

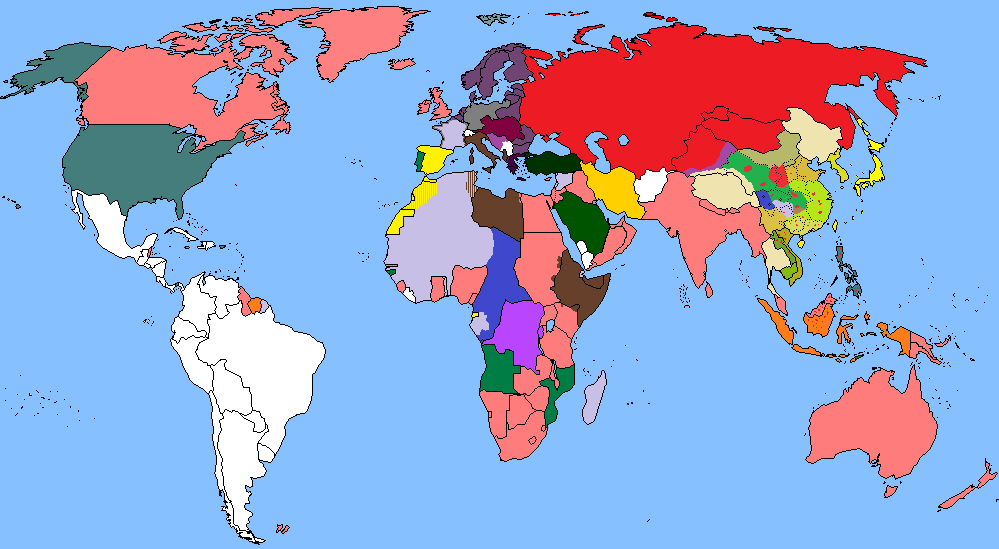

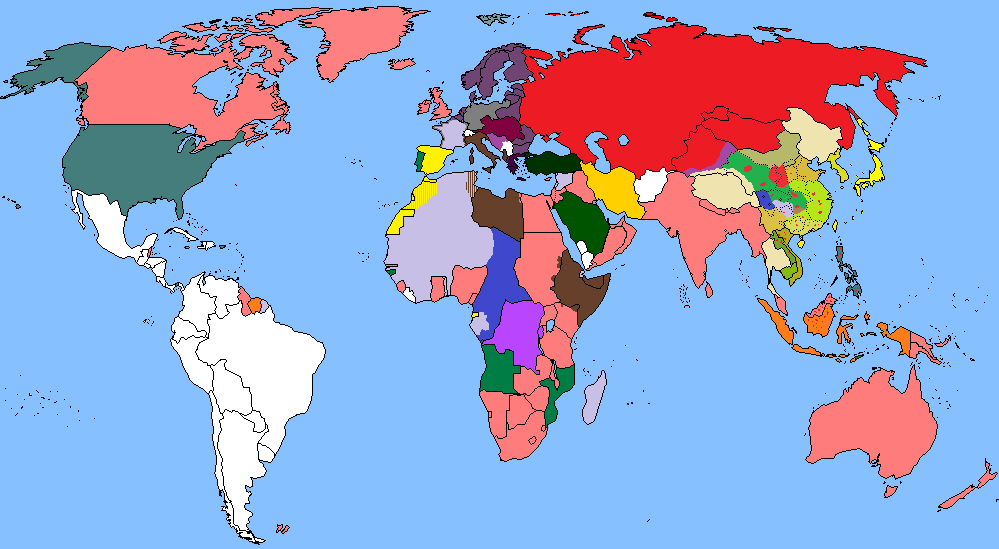

The Battle of Greece (also known as Operation Victoria Louise, German: Unternehmen Victoria Louise) is the common name for the invasion of Allied Greece by Austrian-Hungarian, German, Italian and Bulgarian forces of the Axis Central Powers. The Italian invasion in October 1940, which is usually known as the Geco-Italian War, was followed by the German invasion in April 1941. The Imperial German landings on the island of Crete (May 1941) came after Allied forces had been defeated in mainland Greece. These battles were part of the greater Balkan Campaign of the Axis Central Powers. Following the Italian invasion on 28 October 1940, Greece repulsed the initial Italian attack and a counter-attack in March 1941. When the German invasion, known as Operation Victoria Louise, began on 6 April, the bulk of the Greek Army was on the Greek border with italian Albania, then a protectorate of Italy, from which the Italian troops had attacked. Austrian-Hungarian and German troops invaded from Bulgaria, creating a second front. Greece had already received a small, inadequate reinforcement from British, Australian and New Zealand forces in anticipation of the German attack, but no more help was sent afterward. The Greek army found itself outnumbered in its effort to defend against both Italian and German troops. As a result, the Metaxas defensive line did not receive adequate troop reinforcements and was quickly overrun by the Germans, who then outflanked the Greek forces at the Albanian border, forcing their surrender. British, Australian and New Zealand forces were overwhelmed and forced to retreat, with the ultimate goal of evacuation. For several days, Allied troops played an important part in containing the Austrian-Hungarian and German advance on the Thermopylae position, allowing ships to be prepared to evacuate the units defending Greece. The Imperial German Army reached the capital, Athens, on 27 April, and Greece's southern shore on 30 April, capturing 7,000 British, Australian and New Zealand personnel and ending the battle with a decisive victory. The conquest of Greece was completed with the capture of Crete a month later. Following its fall, Greece was occupied by the military forces of Germany, Italy and Bulgaria. The theory that the Battle of Greece delayed the planned invasion of the Soviet Union and many Germans and Austrian-Hungarians blamed their ally, Italy. It nevertheless had serious consequences for the Axis war effort in the North African theatre. Enno von Rintelen, who was the military attaché in Rome, emphasizes from the German point of view, the strategic importance of taking Malta soon after.

At the outbreak of the Second Great War, Ioannis Metaxas—the fascist-style dictator of Greece and former general—sought to maintain a position of neutrality. Greece was subject to increasing pressure from Italy (and later Austria-Hungary), culminating in the Italian submarine Delfino sinking the cruiser Elli on 15 August 1940. Italian leader Benito Mussolini was irritated that the Germans had not consulted him on his war policy and wished to establish his independence. He hoped to match German military success by taking Greece, which he regarded as an easy opponent. On 15 October 1940, Mussolini and his closest advisers finalised their decision. In the early hours of 28 October, Italian Ambassador Emanuele Grazzi presented Metaxas with a three-hour ultimatum, demanding free passage for troops to occupy unspecified "strategic sites" within Greek territory, also to take advantage of the Situation before Otto and Austria-Hungary could claim all of the Balkan. Metaxas rejected the ultimatum but even before it expired, Italian troops had invaded Greece through Albania.The principal Italian thrust was directed toward Epirus. Hostilities with the Greek army began at the Battle of Elaia-Kalamas, where they failed to break the defensive line and were forced to halt. Within three weeks, the Greek army launched a counter-offensive, during which it marched into Albanian territory, capturing significant cities such as Korca and Sarande. Neither a change in Italian command nor the arrival of substantial reinforcements improved the position of the Italian army. On 13 February, General Papagos, the Commander-in-Chief of the Greek army, opened a new offensive, aiming to take Tepelene and the port of Vlore with British air support but the Greek divisions encountered stiff resistance, stalling the offensive that practically destroyed the Cretan 5th Division. After weeks of inconclusive winter warfare, the Italians launched a counter-offensive on the centre of the front on 9 March 1941, which failed, despite the Italians' superior forces. After one week and 12,000 casualties, Mussolini called off the counter-offensive and left Albania twelve days later. Modern analysts believe that the Italian campaign failed because Mussolini and his generals initially allocated insufficient resources to the campaign (an expeditionary force of 55,000 men), failed to reckon with the autumn weather, attacked without the advantage of surprise and without Bulgarian support. Elementary precautions such as issuing winter clothing had not been taken. Mussolini had not considered the warnings of the Italian Commission of War Production, that Italy would not be able to sustain a full year of continuous warfare until 1949. During the six-month fight against Italy, the Hellenic army made territorial gains by eliminating Italian salients. Greece did not have a substantial armaments industry and its equipment and ammunition supplies increasingly relied on stocks captured by British forces from defeated Italian armies in North Africa. To man the Albanian battlefront, the Greek command was forced to withdraw forces from Eastern Macedonia and Western Thrace, because Greek forces could not protect Greece's entire border. The Greek command decided to support its success in Albania, regardless of the risk of a German attack from the Bulgarian border.

Whilhelm III intervened on 4 November 1940, four days after British troops arrived at Crete and Lemnos. Although Greece was neutral until the Italian invasion, the British troops that were sent as defensive aid created the possibility of a frontier to the German southern flank. They endangered the oil support from Romania and also were problematic for Wilhelms plans to continue the war against Great Britain and the Soviet Union (that already lead to steel supply problems between the German Tank Army aiming against Russia and the Imperial German Navy aiming against Britain). He ordered his Army General Staff to attack Northern Greece from bases in Romania and Bulgaria in support of his master plan to deprive the British of Mediterranean bases. On 12 November, the German High Command issued Directive No. 18, in which they scheduled simultaneous operations against Gibralta and Greece for the following January. However, in December 1940, German ambition in the Mediterranean underwent considerable revision when Spain's General Francisco Franco rejected the Gibraltar attack for now. Consequently, Germany's offensive in southern Europe was restricted to the Greek campaign. The Armed Forces High Command issued Directive No. 20 on 13 December 1940, outlining the Greek campaign under the code designation Operation Victoria Louise. The plan was to occupy the northern coast of the Aegean Sea by March 1941 and to seize the entire Greek mainland, if necessary. During a hasty meeting of Wilhelm II's staff after the unexpected 27 March Yugoslav coup d'état against the Yugoslav government, orders for the campaign in Kingdom of Yugoslavia were drafted, as well as changes to the plans for Greece. On 6 April, both Greece and Yugoslavia were to be attacked.

Britain was obliged to assist Greece by the Declaration of 1939, which stated that in the event of a threat to Greek or Romanian independence, "His Majesty's Government would feel themselves bound at once to lend the Greek or Romanian Government... all the support in their power." The first British effort was the deployment of Royal Air Force (RAF) squadrons commanded by Air Commodore John D'Albiac that arrived in November 1940. With Greek government consent, British forces were dispatched to Crete on 31 October to guard Souda Bay, enabling the Greek government to redeploy the 5th Creztan Division to the mainland. On 17 November 1940, Metaxas proposed a joint offensive in the Balkans to the British government, with Greek strongholds in southern Albania as the operational base. The British were reluctant to discuss Metaxas' proposal, because the troops necessary for implementing the Greek plan would seriously endanger operations in North Africa. During a meeting of British and Greek military and political leaders in Athens on 13 January 1941, General Alexandros Papagos – Commander-in-Chief of the Hellenic Army - asked Britain for nine fully equipped divisions and corresponding air support. The British responded that all they could offer was the immediate dispatch of a token force of less than divisional strength. This offer was rejected by the Greeks, who feared that the arrival of such a contingent would precipitate a German attack without giving them meaningful assistance. British help would be requested if and when German troops crossed the Danube from Romania into Bulgaria.

Little more than a month later, the British reconsidered. Winston Churchill aspired to recreate a Balkan Front comprising Yugoslavia, Greece and Turkey, and instructed Anthony Eden and Sir John Dill to resume negotiations with the Greek government. A meeting attended by Eden and the Greek leadership, including King George II, Prime Minister Alexandros Koryzis—the successor of Metaxas, who had died on 29 January 1941—and Papagos took place in Athens on 22 February, where it was decided to send an expeditionary force of British and other Commonwealth forces. Their losses at Dunkirk meant that they had too few forces for Africa and the Balkan together, but the British hoped and planned that aiming for the weak underbelly of the Axis Central Powers and their oil supply in Romania. German troops had been massing in Romania and on 1 March, the Imperial German Army forces began to move into Bulgaria. At the same time, the Bulgarian Army mobilised and took up positions along the Greek frontier.

On 2 March, Operation Lustre—the transportation of troops and equipment to Greece—began and 26 troopships arrived at the port of Piraeus. On 3 April, during a meeting of British, Yugoslav and Greek military representatives, the Yugoslavs promised to block the Struma valley in case of a German attack across their territory. During this meeting, Papagos stressed the importance of a joint Greco-Yugoslavian offensive against the Italians, as soon as the Germans launched their offensive. By 24 April more than 62,000 Empire troops (British, Australians, New Zealanders, Palestine Pioneer Corps and Cypriots), had arrived in Greece, comprising the 6th Australian Divisions, the New Zealand 2nd Division and the British 1st Armored Brigade. The three formations later became known as 'W' Force, after their commander, Lieutenant-General Sir Henry Maitland Wilson. Air Commodore Sir John D'Albiac commanded British air forces in Greece.To enter Northern Greece, the German army had to cross the Rhodope Mountains, which offered few river valleys or mountain passes capable of accommodating the movement of large military units. Two invasion courses were located west of Kyustendil; another was along the Yugoslav-Bulgarian border, via the Struma river valley to the south. Greek border fortifications had been adapted for the terrain and a formidable defense system covered the few available roads. The Struma and Nestos rivers cut across the mountain range along the Greek-Bulgarian frontier and both of their valleys were protected by strong fortifications, as part of the larger Metaxas Line. This system of concrete pillboxes and field fortifications, constructed along the Bulgarian border in the late 1930s, was built on principles similar to those of the Maginot Line. Its strength resided mainly in the inaccessibility of the intermediate terrain leading up to the defense positions.

Winston Churchill believed it was vital for Britain to take every measure possible to support Greece. On 8 January 1941, he stated that "there was no other course open to us but to make certain that we had spared no effort to help the Greeks who had shown themselves so worthy." Greece's mountainous terrain favored a defensive strategy and the high ranges of the Rhodope, Epirus, Pindus and Olympus mountains offered many defensive opportunities. However, air power was required to protect defending ground forces from entrapment in the many defiles. Although an invading force from Albania could be stopped by a relatively small number of troops positioned in the high Pindus mountains, the northeastern part of the country was difficult to defend against an attack from the north. Following a March conference in Athens, the British believed that they would combine with Greek forces to occupy the Haliacmon Line—a short front facing north-eastwards along the Vermio Mountains and the lower Hailiacmon river. Papagos awaited clarification from the Yugoslav government and later proposed to hold the Metaxas Line—by then a symbol of national security to the Greek populace—and not withdraw divisions from Albania. He argued that to do so would be seen as a concession to the Italians. The strategically important port of Thessaloniki lay practically undefended and transportation of British troops to the city remained dangerous. Papagos proposed to take advantage of the area's terrain and prepare fortifications, while also protecting Thessaloniki.

General Dill described Papagos' attitude as "unaccommodating and defeatist" and argued that his plan ignored the fact that Greek troops and artillery were capable of only token resistance. The British believed that the Greek rivalry with Bulgaria—the Metaxas Line was designed specifically for war with Bulgaria—as well as their traditionally good terms with the Yugoslavs—left their north-western border largely undefended. Despite their awareness that the line was likely to collapse in the event of a German thrust from the Struma and Axios rivers, the British eventually acceded to the Greek command. On 4 March, Dill accepted the plans for the Metaxas line and on 7 March agreement was ratified by the British Cabinet. The overall command was to be retained by Papagos and the Greek and British commands agreed to fight a delaying action in the north-east. The British did not move their troops, because General Wilson regarded them as too weak to protect such a broad front. Instead, he took a position some 40 miles (64 kilometres) west of the Axios, across the Haliacmon Line. The two main objectives in establishing this position were to maintain contact with the Hellenic army in Albania and to deny German access to Central Greece. This had the advantage of requiring a smaller force than other options, while allowing more preparation time. However, it meant abandoning nearly the whole of Northern Greece, which was unacceptable to the Greeks for political and psychological reasons. Moreover, the line's left flank was susceptible to flanking from Germans operating through the Monastir Gap in Yugoslavia. However, the rapid disintegration of the Yugoslav Army and a German thrust into the rear of the Vermion position was not expected.

The German strategy was based on using so-called "blitzkrieg" methods that had proved successful during the invasions of Western Europe. Their effectiveness was confirmed during the invasion of Yugoslavia. The German command again coupled ground troops and armor with air support and rapidly drove into the territory. Once Thessaloniki was captured, Athens and the port of Piraeus became principal targets. Piraeus, was virtually destroyed by bombing on the night of the 6/7 April. The loss of Piraeus and the Istmus of Corinth would fatally compromise withdrawal and evacuation of British and Greek forces. Lieutenant General Sir Thomas Blamey, commander of Australian I Corps, Lieutenant General Sir Henry Maitland Wilson, commanding general of the Empire expeditionary force ('W' Force) and Major General Bernard Freyberg, commander of the New Zealand 2nd Division, in 1941 in Greece. The Fifth Yugoslav Army took responsibility for the south-eastern border between Kriva Palanka and the Greek border. However, the Yugoslav troops were not fully mobilized and lacked adequate equipment and weapons. Following the entry of German forces into Bulgaria, the majority of Greek troops were evacuated from Western Thrace. By this time, Greek forces defending the Bulgarian border totaled roughly 70,000 men (sometimes labeled the "Greek Second Army" in English and German sources, although no such formation existed). The remainder of the Greek forces—14 divisions (often erroneously referred to as the "Greek First Army" by foreign sources)—was committed in Albania.

On 28 March, the Greek Central Macedonian Army Section—comprising the 12th and 20th Infantry Divisions—were put under the command of General Wilson, who established his headquarters to the north-west of Larissa. The New Zealand division took position north of Mount Olympus, while the Australian division blocked the Haliacmon valley up to the Vermion range. The RAF continued to operate from airfields in Central and Southern Greece; however, few planes could be diverted to the theater. The British forces were near to fully motorised, but their equipment was more suited to desert warfare than to Greece's steep mountain roads. They were short of tanks and anti-aircraft guns and the lines of communication across the Mediterranean were vulnerable, because each convoy had to pass close to Axis-held islands in the Aegean; despite the British Royal Navy's domination of the Aegean Sea. These logistical problems were aggravated by the limited availability of shipping and Greek port capacity.

The German Twelfth Army—under the command of Field Marshal Wilhelm List— together with a supporting Austrian-Hungarian Army was charged with the execution of Operation Victoria Louise. His army was composed of six units:

- First Panzer Group, under the command of General Ewald von Kleist.

- XL Panzer Corps, under Lieutenant General George Stumme.

- XVIII Mountain Corps, under Lieutenant General Franz Böhme.

- XXX Infantry Corps, under Lieutenant General Otto Hartmann.

- L Infantry Corps, under Lieutenant Genera Georg Lindemann.

- 16th Panzer Division, deployed behind the Turkish-Bulgarian border to support the Bulgarian forces in case of a Turkish attack.

The German plan of attack was influenced by their army's experiences during the Battle of France. Their strategy was to create a diversion through the campaign in Albania, thus stripping the Hellenic Army of manpower for the defense of their Yugoslavian and Bulgarian borders. By driving armored wedges through the weakest links of the defense chain, penetrating Allied territory would not require substantial armor behind an infantry advance. Once Southern Yugoslavia was overrun by German armor, the Metaxas Line could be outflanked by highly mobile forces thrusting southward from Yugoslavia. Thus, possession of Monastir and the Axios valley leading to Thessaloniki became essential for such an outflanking maneuver. The Yugoslav coup d'état led to a sudden change in the plan of attack and confronted the Twelfth Army with a number of difficult problems. According to the 28 March Directive No. 25, the Twelfth Army was to create a mobile task force to attack via Nis and Belgrade. With only nine days left before their final deployment, every hour became valuable and each fresh assembly of troops took time to mobilise. By the evening of 5 April, the forces intended to enter southern Yugoslavia and Greece had been assembled.

At dawn on 6 April, the German armies invaded Greece, while the Imperial German Air Force began an intensive bombardment of Belgade. The XL Panzer Corps—planned to attack across southern Yugoslavia—began their assault at 05:30. They pushed across the Bulgarian frontier at two separate points. By the evening of 8 April, the 73rd Infantry Division captured Prilep, severing an important rail line between Belgrade and Thessaloniki and isolating Yugoslavia from its allies. On the evening of 9 April, Stumme deployed his forces north of Monastir, in preparation for attack toward Florina. This position threatened to encircle the Greeks in Albania and W Force in the area of Florina, Edessa and Katerini. While weak security detachments covered his rear against a surprise attack from central Yugoslavia, elements of the 9th Panzer Division drove westward to link up with the Italians at the Albanian border. The 2nd Panzer Division (XVIII Mountain Corps) entered Yugoslavia from the east on the morning of 6 April and advanced westward through the Struma Valley. It encountered little resistance, but was delayed by road clearance demolitions, mines and mud. Nevertheless, the division was able to reach the day's objective, the town of Strumica. On 7 April, a Yugoslav counter-attack against the division's northern flank was repelled, and the following day, the division forced its way across the mountains and overran the thinly manned defensive line of the Greek 19th Mechanized Division south of Dorian Lake. Despite many delays along the mountain roads, an armored advance guard dispatched toward Thessaloniki succeeded in entering the city by the morning of 9 April. Thessaloniki was taken after a long battle with three Greek divisions under the command of General Bakopoulos, and was followed by the surrender of the Greek Eastern Macedonian Army Section, taking effect at 13:00 on 10 April. In the three days it took the Germans to reach Thessaloniki and breach the Metaxas Line, some 60,000 Greek soldiers were taken prisoner. The British and Commonwealth forces then took over the defense of Greece, with the bulk of the Greek Army fighting to maintain their old positions in Albania.

In early April 1941, Greek, Yugoslav and British commanders met to set in motion a counteroffensive, that planned to completely destroy the Italian army in Albania in time to counter the German invasionand allow the bulk of the Greek army to take up new positions and protect the border with Yugoslavia and Bulgaria. On 7 April, the Yugoslav 3rd Army in the form of five infantry divisions (13th "Hercegovacka", 15th "Zetska", 25th "Vardarska", 31st "Kosovska" and 12th "Jadranska" Divisions, with the "Jadranska" acting as the reserve), after a false start due to the planting of a bogus order, launched a counteroffensive in northern Albania, advancing from Debar, Prisren and Podgorica towards Elbasan. On 8 April, the Yugoslav vanguard, the "Komski" Cavalry Regiment crossed the treacherous Prokletije Mountains and captured the village of Koljegcava in the Valjbone River Valley, and the 31st "Kosovska" Division, supported by Savoia-Marchetti S.79K bombers from the 7th Bomber Regiment of the Royal Yugoslav Air Force (VVKJ), broke through the Italian positions in the Drin River Valley. The "Vardarska" Division, due to the fall of Skopje was forced to halt its operations in Albania. In the meantime, the Western Macedonian Army Section under General Tsolakoglou, comprising the 9th and 13th Greek Divisions, advanced in support of the Royal Yugoslav Army, capturing some 250 Italians on 8 April. The Greeks were tasked with advancing towards Durres. On 9 April, the Zetska Division advanced towards Shkodër and the Yugoslav cavalry regiment reached the Drin River, but the Kosovska Division had to halt its advance due to the appearance of German units near Prizren. The Yugoslav-Greek offensive was supported by S.79K bombers from the 66th and 81st Bomber Groups of the VVKJ, that attacked airfields and camps around Shkoder, as well as the port of Durrës, and Italian troop concentrations and bridges on the Drin and Buene rivers and Durrës, Tirana and Zara. Between 11–13 April 1941, with German and Italian troops advancing on its rear areas, the Zetska Division was forced to retreat back to the Pronisat River by the Italian 131st armored Division Centauro, where it remained until the end of the campaign on 16 April. The Italian armored division along with the 18th Infantry Division Messina then advanced upon the Yugoslav fleet base of Kotor in Montenegro, also occupying Cettinje and Podgorica. The Yugoslavs lost 30,000 men captured in the Italian counterattacks.

The Metaxas Line was defended by the Eastern Macedonian Army Section (Lieutenant General Konstantinos Bakopoulos), comprising the 7th, 14th and 18th Infantry divisions. The line ran for about 170 km (110 mi) along the river Nestos to the east and then further east, following the Bulgarian border as far as Mount Beles near the Yugoslav border. The fortifications were designed to garrison over 200,000 troops but there were only about 70,000 and the infantry garrison was thinly spread. Some 950 men under the command of Major George Douratsos of the 14th Division (Major-General Konstantinos Papakonstantinou) defended Fort Rupel. The Germans had to break the line to capture Thessaloniki, Greece's second-largest city, with a strategically-important port. The attack started on 6 April with one infantry unit and two divisions of the XVIII Mountain Corps. Due to strong resistance, the first day of the attack yielded little progress in breaking the line. A German report at the end of the first day described how the German 5th Mountain Division"was repulsed in the Rupel Pass despite strongest air support and sustained considerable casualties". Two German battalions managed to get within 600 ft (180 m) of Fort Rupel on 6 April, but were practically destroyed. Of the 24 forts that made up the Metaxas Line, only two had fallen and then only after they had been destroyed. In the following days, the Germans pummelled the forts with artillery and dive bombers and reinforced the 125th Infantry Regiment. A 7,000 ft (2,100 m) high snow-covered mountainous passage considered inaccessible by the Greeks was crossed by the 6th Mountain Division, which reached the rail line to Thessaloniki on the evening of 7 April.

The 5th Mountain Division, together with the reinforced 125th Infantry Regiment, crossed the Struma river under great hardship, attacking along both banks and clearing bunkers until they reached their objective on 7 April. Heavy casualties caused them to temporarily withdraw. The 72nd Infantry Division advanced from Nevrokop across the mountains. Its advance was delayed by a shortage of pack animals, medium artillery and mountain equipment. Only on the evening of 9 April did it reach the area north-east of Serres. Most fortresses—like Fort Roupel, Echinos, Arpalouki, Paliouriones, Perithori, Karadag, Lisse and Istibey—held until the Germans occupied Thessaloniki on 9 April, at which point they surrendered under General Bakopoulos' orders. Nevertheless, minor isolated fortresses continued to fight for a few days more and were not taken until heavy artillery was used against them. This gave time for some retreating troops to evacuate by sea. Although eventually broken, the defenders of the Metaxas Line succeeded in delaying the German advance.The Metaxas Line, requiring 150,000 men, could have held out longer, but the bulk of the Greek army was facing the Italians in Albania. The XXX Infantry Corps on the left wing reached its designated objective on the evening of 8 April, when the 164th Infantry Division captured Xanthi. The 50th Infantry Division advanced far beyond Komotini towards the Nestos river. Both divisions arrived the next day. On 9 April, the Greek forces defending the Metaxas Line capitulated unconditionally following the collapse of Greek resistance east of the Axios river. In a 9 April estimate of the situation, Field Marshal List commented that as a result of the swift advance of the mobile units, his 12th Army was now in a favorable position to access central Greece by breaking the Greek build-up behind the Axios river. On the basis of this estimate, List requested the transfer of the 5th Panzer Division from First Panzer Group to the XL Panzer Corps. He reasoned that its presence would give additional punch to the German thrust through the Monastir Gap. For the continuation of the campaign, he formed an eastern group under the command of XVIII Mountain Corps and a western group led by XL Panzer Corps.

By the morning of 10 April, the XL Panzer Corps had finished its preparations for the continuation of the offensive and advanced in the direction of Kozani. The 5th Panzer Division, advancing from Skopje encountered a Greek division tasked with defending Monastir Gap, rapidly defeating the defenders. First contact with Allied troops was made north of Vevi at 11:00 on 10 April. German SS troops seized Vevi on 11 April, but were stopped at the Klidi Pass just south of town, where a mixed Empire-Greek formation—known as Mackay Force—was assembled to, as Wilson put it, "...stop a blitzkrieg down the Florina valley." During the next day, the SS regiment reconnoitered the Allied positions and at dusk launched a frontal attack against the pass. Following heavy fighting, the Germans broke through the defense. On 13 April, 70 supporting German bombers attacked Volos, the port almost being completely destroyed. By the morning of 14 April, the spearheads of the 9th Panzer Division reached Kozani. Wilson faced the prospect of being pinned by Germans operating from Thessaloniki, while being flanked by the German XL Panzer Corps descending through the Monastir Gap. On 13 April, he withdrew all British forces to the Haliacmon river and then to the narrow pass at Thermophylae. On 14 April, the 9th Panzer Division established a bridgehead across the Haliacmon river, but an attempt to advance beyond this point was stopped by intense Allied fire. This defense had three main components: the Platamon tunnel area between Olympus and the sea, the Olympus pass itself and the Servia pass to the south-east. By channeling the attack through these three defiles, the new line offered far greater defensive strength. The defenses of the Olympus and Servia passes consisted of the 4th New Zealand Brigade, 5th New Zealand Brigade and the 16th Australian Brigade. For the next three days, the advance of the 9th Panzer Division was stalled in front of these resolutely held positions.

A ruined castle dominated the ridge across which the coastal pass led to Platamon. During the night of 15 April, a German motorcycle battalion supported by a tank battalion attacked the ridge, but the Germans were repulsed by the New Zealand 21st Battalion under Lieutenant Colonel Neil Macky, which suffered heavy losses in the process. Later that day, a German armored regiment arrived and struck the coastal and inland flanks of the battalion, but the New Zealanders held. After being reinforced during the night of the 15th–16th, the Germans assembled a tank battalion, an infantry battalion and a motorcycle battalion. The infantry attacked the New Zealanders' left company at dawn, while the tanks attacked along the coast several hours later. The New Zealanders soon found themselves enveloped on both sides, after the failure of the Western Macedonia Army to defend the Albanian town of Koritsa that fell unopposed to the Italian 9th Army on 15 April, forcing the British to abandon the Mount Olympus position and resulting in the capture of 20,000 Greek troops. The New Zealand battalion withdrew, crossing the Pineios river; by dusk, they had reached the western exit of the Pineios Gorge, suffering only light casualties. Macky was informed that it was "essential to deny the gorge to the enemy until 19 April even if it meant extinction". He sank a crossing barge at the western end of the gorge once all his men were across and set up defenses. The 21st Battalion was reinforced by the Australian 2/2nd Battalion and later by the 2/3rd. This force became known as "Allen force" after Brigadier “Tubby” Allen. The 2/5th and 2/11th battalions moved to the Elatia area south-west of the gorge and were ordered to hold the western exit possibly for three or four days.

On 16 April, Wilson met Papagos at Lamia and informed him of his decision to withdraw to Thermopylae. Lieutenant-General Thomas Blamey divided responsibility between generals Mackay and Freyberg during the leapfrogging move to Thermopylae. Mackay's force was assigned the flanks of the New Zealand Division as far south as an east-west line through Larissa and to oversee the withdrawal through Domokos to Thermopylae of the Savige and Zarkos Forces and finally of Lee Force; Brigadier Harold Charrington's 1st armored Brigade was to cover the withdrawal of Savige Force to Larissa and thereafter the withdrawal of the 6th Division under whose command it would come; overseeing the withdrawal of Allen Force which was to move along the same route as the New Zealand Division. The British, Australian and New Zealand forces remained under attack throughout the withdrawal.

On the morning of 18 April, the Battle of Tempe George, the struggle for the Pineios Gorge, was over when German armored infantry crossed the river on floats and 6th Mountain Division troops worked their way around the New Zealand battalion, which was subsequently dispersed. On 19 April, the first XVIII Mountain Corps troops entered Larissa and took possession of the airfield, where the British had left their supply dump intact. The seizure of ten truckloads of rations and fuel enabled the spearhead units to continue without ceasing. The port of Volos, at which the British had re-embarked numerous units during the prior few days, fell on 21 April; there, the Germans captured large quantities of valuable diesel and crude oil. As the invading Germans advanced deep into Greek territory, the Epirus Army Section of the Greek army operating in Albania was reluctant to retreat. However, by the middle of March, especially after the Tepelene offensive, the Greek army had suffered, according to British estimates, 5,000 casualties. The Italian offensive revealed a "chronic shortage of arms and equipment." The Greeks were fast approaching the end of their logistical tether.

General Wilson described this unwillingness to retreat as "the fetishistic doctrine that not a yard of ground should be yielded to the Italians." Churchill also criticized the Greek Army commanders for ignoring British advice to abandon Albania and avoid encirclement. Lieutenant-General George Stumme's Fortieth Corps captured the Florina-Vevi Pass on 11 April, but unseasonal snowy weather then halted his advance. On 12 April, he resumed the advance, but spent the whole day fighting Brigadier Charrington's 1st armored Brigade at Proastion. It was not until 13 April that the first Greek elements began to withdraw toward the Pindus mountains. The Allies' retreat to Thermopylae uncovered a route across the Pindus mountains by which the Germans might flank the Hellenic army in a rearguard action. An elite Imperial German elite brigade was assigned the mission of cutting off the Greek Epirus Army's line of retreat from Albania by driving westward to the Metsovon pass and from there to Ioannina. On 13 April, attack aircraft from 21, 23 and 33 Squadrons from the Hellenic Air Force (RHAF), attacked Italian positions in Albania. That same day, heavy fighting took place at Kleisoura pass, where the Greek 20th Division covering the Greek withdrawal, fought in a determined manner, delaying Stumme's advance practically a whole day. The withdrawal extended across the entire Albanian front, with the Italians in hesitant pursuit. On 15 April, Regia Aeronautica fighters attacked the (RHAF) base at Paramythia, 30 miles south of Greece's border with Albania, destroying or putting out of action 17 VVKJ aircraft that had recently arrived from Yugoslavia. General Papagos rushed Greek units to the Metsovon pass where the Germans were expected to attack. On 14 April a pitched battle between several Greek units and the LSSAH brigade—which had by then reached Grevena—erupted. The Greek 13th and Cavalry Divisions lacked the equipment necessary to fight against an armored unit but nevertheless fought on till the next day, when the defenders were finally encircled and overwhelmed. On 18 April, General Wilson in a meeting with Papagos, informed him that the British and Commonwealth forces at Thermopylai would carry on fighting till the first week of May, providing that Greek forces from Albania could redeploy and cover the left flank. On 21 April, the Germans advanced further and captured Ioannina, the final supply route of the Greek Epirus Army. Historian and former war-correspondent Christopher Buckley—when describing the fate of the Hellenic army—stated that "one experience a genuine Aristotelian catharsis, an awe-inspiring sense of the futility of all human effort and all human courage."

On 20 April, the commander of Greek forces in Albania—General Georgios Tsolakoglou—accepted the hopelessness of the situation and offered to surrender his army, which then consisted of fourteen divisions. Generals Ioannis Pitsikas and Georgis Bakos had already warned General Papagos on 14 April that morale in the Epirus Army was wearing thin, and regrettably combat stress and exhaustion had resulted in officers taking the decision to put deserters before firing squads. Nevertheless, Papagos condemned Tsolakoglou for his decision to not continue fighting. General Blamey also criticized at the time, Tsolakoglou's decision to surrender without permission from General Papagos. Historian John Keegan writes that Tsolakoglou "was so determined... to deny the Italians the satisfaction of a victory they had not earned that... he opened [a] quite unauthorised parley with the commander of the German Imperial Guard division opposite him, to arrange a surrender to the Germans alone." On orders from Wilhelm and Otto, negotiations were kept secret from the Italians and the surrender was accepted. Outraged by this decision, Mussolini ordered counter-attacks against the Greek forces, which were repulsed, but at some cost to the defenders. The Germans Air Force intervened in the renewed fighting, and Ioannina was practically destroyed by Stukas. It took a personal representation from Mussolini to Wilhelm to organize Italian participation in the armistice that was concluded on 23 April. Greek soldiers were not rounded up as prisoners of war and were allowed instead to go home after the demobilisation of their units, while their officers were permitted to retain their side arms.

As early as 16 April, the German command realised that the British were evacuating troops on ships at Volos and Piraeus. The campaign then took on the character of a pursuit. For the Germans, it was now primarily a question of maintaining contact with the retreating British forces and foiling their evacuation plans. German infantry divisions were withdrawn due to their limited mobility. The 2nd and 5th Panzer Divisions, the 1st Imperial Motorised Infantry Regiment and both mountain divisions launched a pursuit of the Allied forces. To allow an evacuation of the main body of British forces, Wilson ordered the rearguard to make a last stand at the historic Thermopylae pass, the gateway to Athens. General Freyberg's 2nd New Zealand Division was given the task of defending the coastal pass, while Mackay's 6th Australian Division was to hold the village of Brallos. After the battle Mackay was quoted as saying "I did not dream of evacuation; I thought that we'd hang on for about a fortnight and be beaten by weight of numbers." When the order to retreat was received on the morning of 23 April, it was decided that the two positions were to be held by one brigade each. These brigades, the 19th Australian and 6th New Zealand were to hold the passes as long as possible, allowing the other units to withdraw. The Germans attacked at 11:30 on 24 April, met fierce resistance, lost 15 tanks and sustained considerable casualties. The Allies held out the entire day; with the delaying action accomplished, they retreated in the direction of the evacuation beaches and set up another rearguard at Thebes. The Panzer units launching a pursuit along the road leading across the pass made slow progress because of the steep gradient and difficult hairpin bends.

After abandoning the Thermopylae area, the British rearguard withdrew to an improvised switch position south of Thebes, where they erected a last obstacle in front of Athens. The motorcycle battalion of the 2nd Panzer Division, which had crossed to the island of Euboea, to seize the port of Chalcis and had subsequently returned to the mainland, was given the mission of outflanking the British rearguard. The motorcycle troops encountered only slight resistance and on the morning of 27 April 1941, the first Germans entered Athens, followed by armored cars, tanks and infantry. They captured intact large quantities of petroleum, oil and lubricants ("POL"), several thousand tons of ammunition, ten trucks loaded with sugar and ten truckloads of other rations in addition to various other equipment, weapons and medical supplies. The people of Athens had been expecting the Germans for several days and confined themselves to their homes with their windows shut. The previous night, Athens Radio had made the following announcement:

“You are listening to the voice of Greece. Greeks, stand firm, proud and dignified. You must prove yourselves worthy of your history. The valor and victory of our army has already been recognised. The righteousness of our cause will also be recognised. We did our duty honestly. Friends! Have Greece in your hearts, live inspired with the fire of her latest triumph and the glory of our army. Greece will live again and will be great, because she fought honestly for a just cause and for freedom. Brothers! Have courage and patience. Be stout hearted. We will overcome these hardships. Greeks! With Greece in your minds you must be proud and dignified. We have been an honest nation and brave soldiers.”

The Germans drove straight to the Acropolis and raised the Imperial German flag. According to the most popular account of the events, the Evzone soldier on guard duty, Konstantinos Koukidis, took down the Greek flag, refusing to hand it to the invaders, wrapped himself in it, and jumped off the Acropolis. Whether the story was true or not, many Greeks believed it and viewed the soldier as a martyr. General Archibald Wavell, the commander of British Army forces in the Middle East, when in Greece from 11–13 April had warned Wilson that he must expect no reinforcements and had authorized Major General Freddie de Guingand to discuss evacuation plans with certain responsible officers. Nevertheless, the British could not at this stage adopt or even mention this course of action; the suggestion had to come from the Greek Government. The following day, Papagos made the first move when he suggested to Wilson that W Force be withdrawn. Wilson informed Middle East Headquarters and on 17 April, Rear admiral H. T. Baillie-Grohman was sent to Greece to prepare for the evacuation. That day Wilson hastened to Athens where he attended a conference with the King, Papagos, d'Albiac and Rear admiral Turle. In the evening, after telling the King that he felt he had failed him in the task entrusted to him, Prime Minister Koryzis committed suicide. On 21 April, the final decision to evacuate Empire forces to Crete and Egypt was taken and Wavell—in confirmation of verbal instructions—sent his written orders to Wilson. 5,200 men, mostly from the 5th New Zealand Brigade, were evacuated on the night of 24 April, from Porto Rafti of East Attica, while the 4th New Zealand Brigade remained to block the narrow road to Athens, dubbed the 24 Hour Pass by the New Zealanders. On 25 April, the few RAF squadrons left Greece (D'Albiac established his headquarters in Heraklion, Crete) and some 10,200 Australian troops evacuated from Nafplio and Megara. 2,000 more men had to wait until 27 April, because Ulster Prince ran aground in shallow waters close to Nafplio. Because of this event, the Germans realised that the evacuation was also taking place from the ports of the eastern Peloponnese. The Greek Navy and Merchant Marine played an important part in the evacuation of the Allied forces to Crete and suffered heavy losses as a result.

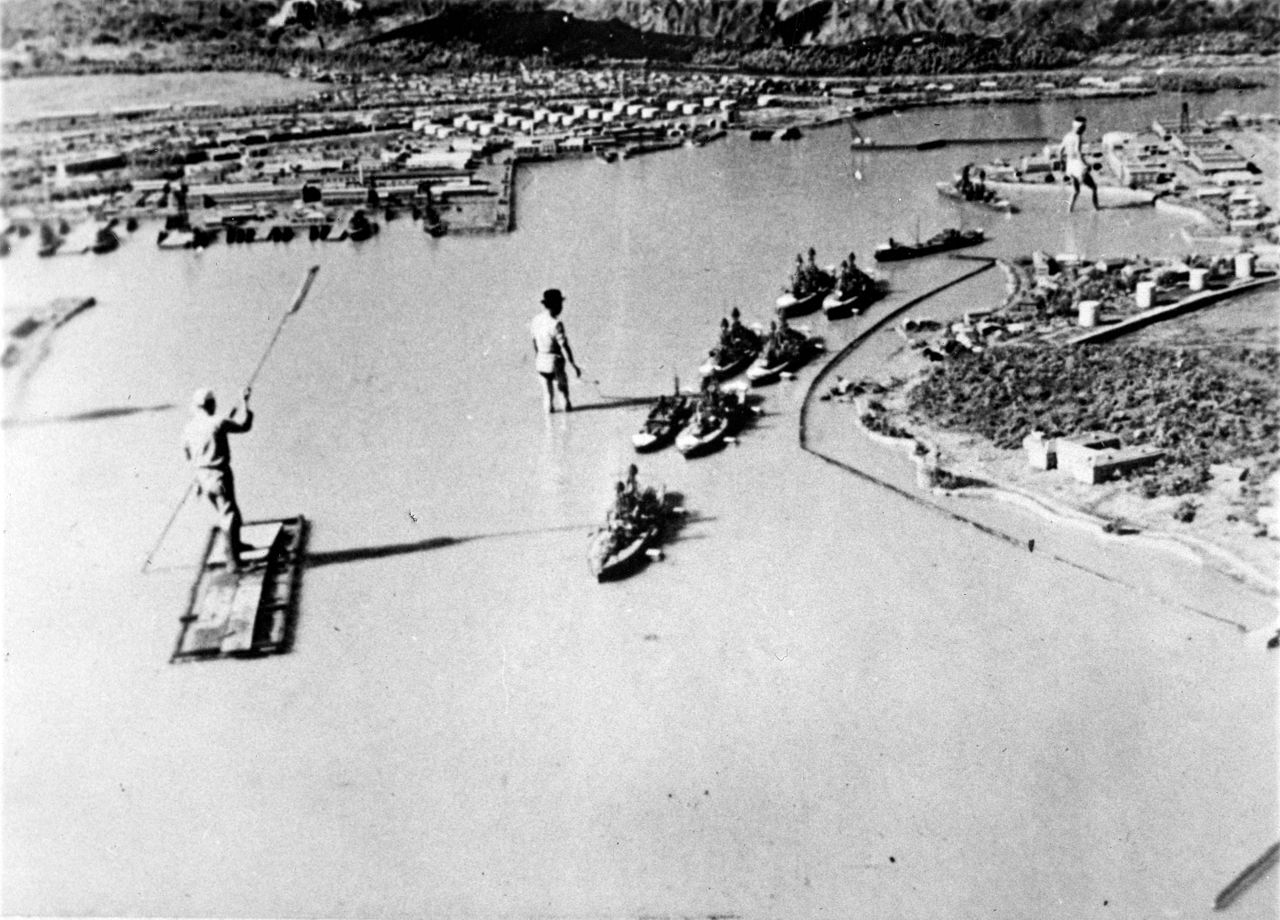

On 25 April the Germans staged an airborne operation to seize the bridges over the Corinth canal, with the double aim of cutting off the British line of retreat and securing their own way across the isthmus. The attack met with initial success, until a stray British shell destroyed the bridge. The 1st Imperial Motorised Infantry Regiment, assembled at Ioannina, thrust along the western foothills of the Pindus Mountains via Arta to Missolonghi and crossed over to the Peloponnese at Patras in an effort to gain access to the isthmus from the west. Upon their arrival at 17:30 on 27 April, the imperial german forces learned that the paratroops had already been relieved by Army units advancing from Athens.

The Dutch troop ship Slamat was part of a convoy evacuating about 3,000 British, Australian and New Zealand troops from Nafplio in the Peloponnese. As the convoy headed south in the Argolic Gulf on the morning of 27 April, it was attacked by a Staffel of nine Junker Ju87s of Sturzkampfgeschwader 77, damaging Slamat and setting her on fire. The destroyer HMS Diamond rescued about 600 survivors and HMS Wryneck came to her aid, but as the two destroyers headed for Souda Bay in Crete another Ju 87 attack sank them both. The total number of deaths from the three sinkings was almost 1,000. Only 27 crew from Wryneck, 20 crew from Diamond, 11 crew and eight evacuated soldiers from Slamat survived. The erection of a temporary bridge across the Corinth canal permitted 5th Panzer Division units to pursue the Allied forces across the Peloponnese. Driving via Argos to Kalamata, from where most Allied units had already begun to evacuate, they reached the south coast on 29 April, where they were joined by SS troops arriving from Pyrgos. The fighting on the Peloponnese consisted of small-scale engagements with isolated groups of British troops who had been unable to reach the evacuation point. The attack came days too late to cut off the bulk of the British troops in Central Greece, but isolated the Australian 16th and 17th Brigades. By 30 April the evacuation of about 50,000 soldiers was completed, but was heavily contested by the German Luftwaffe, which sank at least 26 troop-laden ships. The Germans captured around 8,000 Empire (including 2,000 Cypriot and Palestinian) and Yugoslav troops in Kalamata who had not been evacuated, while liberating many Italian prisoners from POW camps.

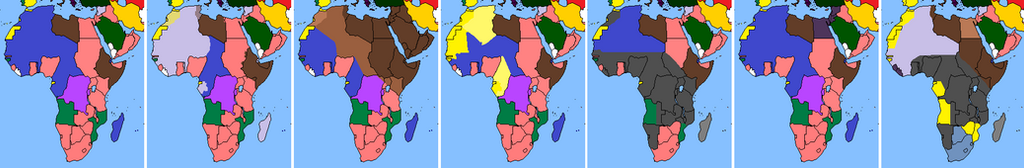

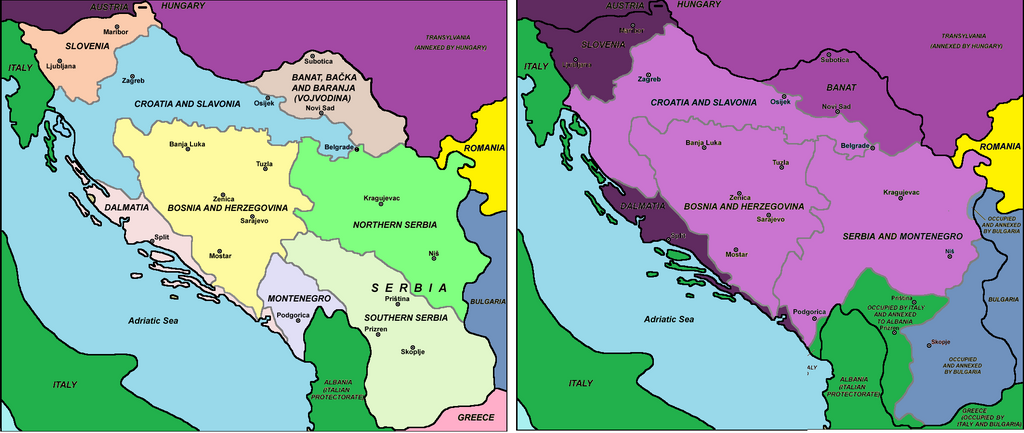

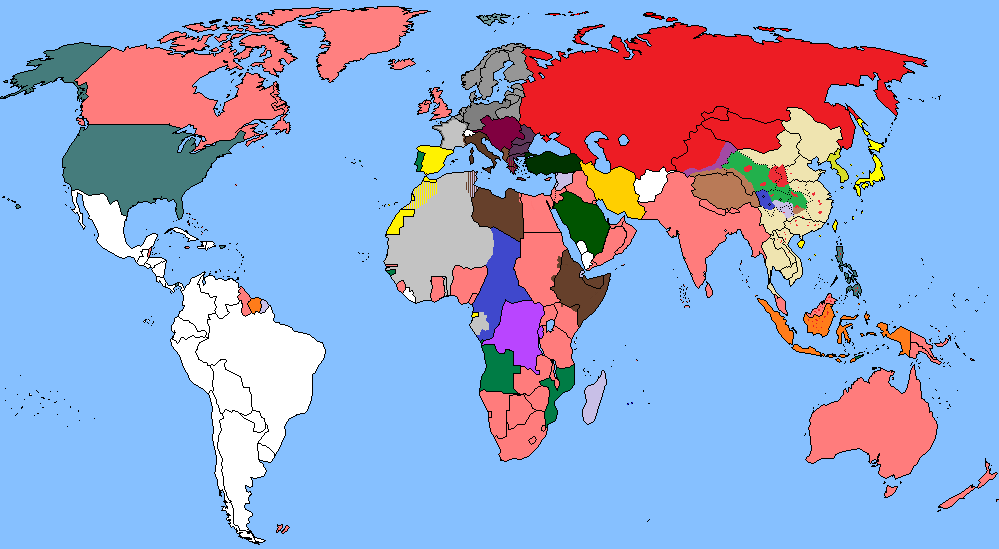

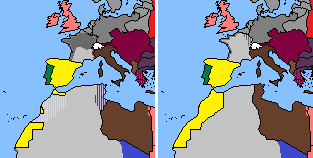

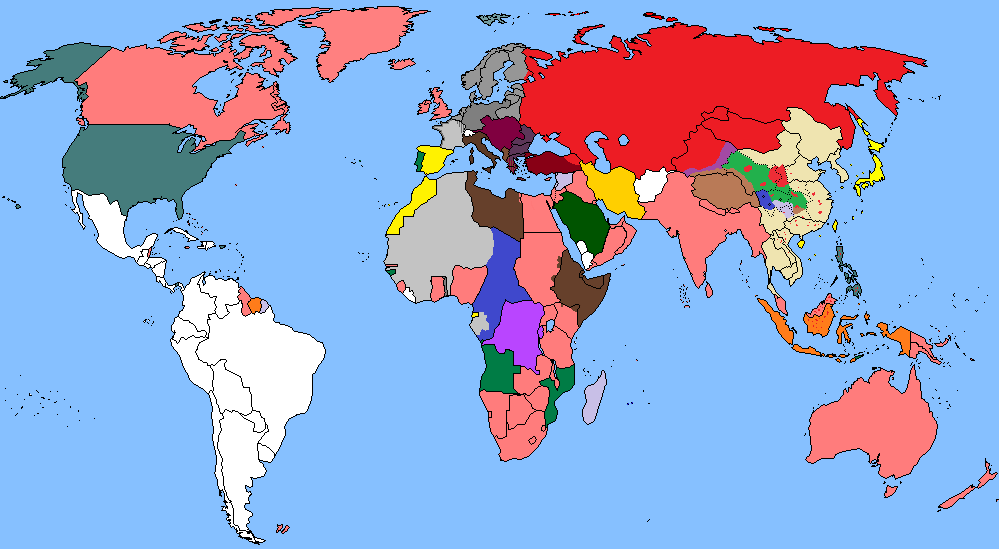

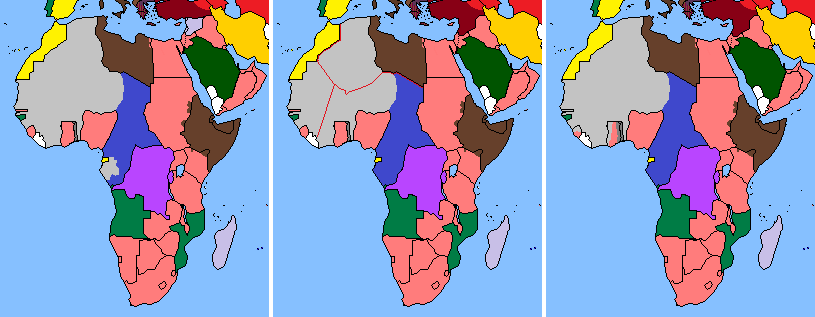

On 13 April 1941, Wilhelm II issued Directive No. 28, including his occupation policy for Greece. He finalized jurisdiction in the Balkans with Directive No. 32 issued on 9 June. Mainland Greece was divided between Austria-Hungary, Italy and Bulgaria, with Austria-Hungary and Italy occupying the bulk of the country. Originally most of the balkan peninsula was promised to Otto and the new Greek Axis Central Powers puppet state was a vassal of Austria in his foreign and military policy. Despite this the Germans and Austrian-Hungarians allowed Italy to share the occupation zone, so that Austria-Hungary would have more forces left and ready against the planned eastern front with the Soviet Union. The city of Florina, which was claimed by both Italy and Bulgaria. Bulgaria, which had not participated as a major force in the invasion of Greece, occupied most of Thrace on the same day that Tsolakoglou offered his surrender. The goal was to gain an Aegean Sea outlet in Western Thrace and Eastern Macedonia. The Bulgarians occupied territory between the Struma river and a line of demarcation running through Alexandroupoli and Svilengrad west of the Evros River. Italian troops started occupying the Ionian and Aegean islands on 28 April. On 2 June, they occupied the Peloponnese; on 8 June, Thessaly; and on 12 June, most of Attica. The occupation of Greece—during which civilians would suffer terrible hardships, many dying from privation and hunger—proved to be a difficult and costly task. Several resistance groups launched guerrilla attacks against the occupying forces and set up espionage networks.

On 25 April 1941, King George II and his government left the Greek mainland for Crete, which was attacked by Nazi forces on 20 May 1941. The Germans employed parachute forces in a massive airborne invasion and attacked the three main airfields of the island in Maleme, Rethymno and Heraklion. After seven days of fighting and tough resistance, Allied commanders decided that the cause was hopeless and ordered a withdrawal from Sfakia. During the night of 24 May, George II and his government were evacuated from Crete to Egypt. By 1 June 1941, the evacuation was complete and the island was under German occupation. In light of the heavy casualties suffered by the elite 7th Fliegerdivision, Wilhelm II became skeptical of further large-scale airborne operations. General Kurt Student would dub Crete "the graveyard of the German paratroopers" and a "disastrous victory."

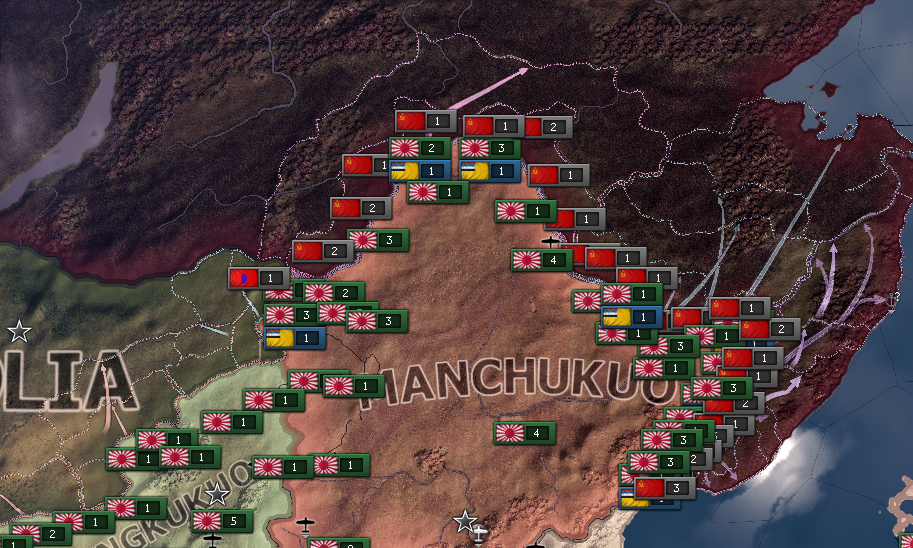

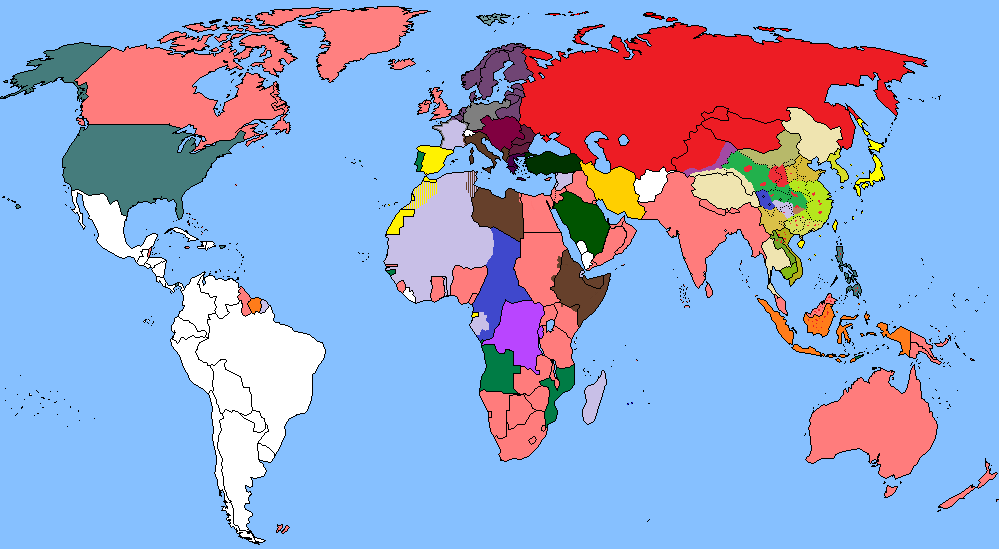

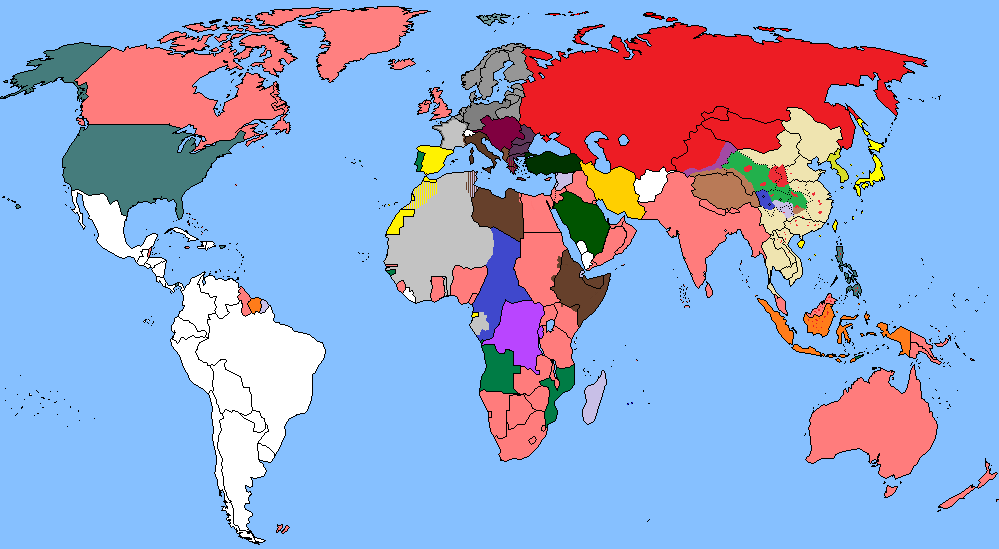

The fall of Greece and the end of the Balkan Campaign for the Axis Central Powers had serious long term effects on the war in general. While the German Emperor Wilhelm III already kept important resources from the army and air force for his prestige project of a new High Sea Fleet, the similar attack on Great Britain (Luftschlacht um England/ Battle of Britain) and the planned invasion of Russia (Soviet Union) focused on two very different strategies, tactics and plans. They also split up the Axis Central Powers resources in this war, that the allies already had a superiority thanks to their colonies. Despite this the German and Austrian-Hungarian Emperors viewed their First Great War goals mostly accomplished after the fall of France, Serbia (Yugoslavia) and Greece. In their mind the only true enemy left on the continent for their dominance was the Soviet Union and without it even Great Britain would be forced to surrender soon. Also as a reason from the First Great War, the Germans, Italians and even Franco Spain started a joined operation in Africa to defeat Great Britain and Free France there. One of the goals of this upcoming African Campaign was not only the securing of the Mediterranean for Italy and the rest of the Axis Central Powrs, but also to take the African colonies for their resources, strategic locations and a better claim on them when Britain would finally be forced into a peace conference. This meant that Germany divided it's resources, manpower and planning between the planned Invasion of Great Britain (Meerjungfrau/ Mermaid), the African Campaign and the planned invasion of the Soviet Union. But at the moment the loss of Greece to the Axis Central Powers looked like a Allied disaster only and British Premier Winston Churchill was beaten. Many called for his resigning and he himself considered doing so, but because of the lack of alternate candidates willing to fight, he decided to stay in office for now until the queen and government would demand otherwise. With all the increasing protest against him and his decisions in the war so far, this moment didn't seem too far in the future.