Oh yeah, China's in the middle of a huge cultural and economic shifts, and it'll be a very different country from OTL. This Mao is unrelated to the infamous one from OTL, it's actually a decently common surname over there.Holy hell, Mao has gone in and became alot of stuff here. Though I imagine who is this one here. Is he original or the one we all know, but different?

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The American System: A Henry Clay TL

- Thread starter TheHedgehog

- Start date

It looks like h's an original character. Nice!Oh yeah, China's in the middle of a huge cultural and economic shifts, and it'll be a very different country from OTL. This Mao is unrelated to the infamous one from OTL, it's actually a decently common surname over there.

Glad to see that China managed a transition to democracy pretty easily, though I'm concerned by Han Chinese being made the only language; assuming this China has the OTL Qing Empire's borders that's a lot of people not included.

I also wonder if this different China could reflect on the glimpse into the future of America we've seen. No Mao Zedong has a huge impact on the US economy, as there would presumably be far more trade between China and the US; this could cause a much earlier resurgence in protectionism.

I also wonder if this different China could reflect on the glimpse into the future of America we've seen. No Mao Zedong has a huge impact on the US economy, as there would presumably be far more trade between China and the US; this could cause a much earlier resurgence in protectionism.

Yah, China, like OTL Turkey, is going to have its hands full with ethnic unrest, especially in Tibet and MongoliaGlad to see that China managed a transition to democracy pretty easily, though I'm concerned by Han Chinese being made the only language; assuming this China has the OTL Qing Empire's borders that's a lot of people not included.

I also wonder if this different China could reflect on the glimpse into the future of America we've seen. No Mao Zedong has a huge impact on the US economy, as there would presumably be far more trade between China and the US; this could cause a much earlier resurgence in protectionism.

US politicians will definitely use China as a boogeyman in calling for protectionism, though the US and China would be more friendly rivals than enemies

Thanks!Good stuff!

89. All Politics is Local

89. All Politics is Local

“As the Ottoman Empire continued to modernize and focus on Rumelia, a sense of Arabian alienation grew in the Empire’s southern territories. Oil was discovered in the years following the Treaty of London, but this only heightened the alienation. In the 1923 elections, the decentralist Party of Regions suffered a landslide defeat as Arab constituencies voted in large numbers for local independents, while their National Constitutionalist coalition partners 0nly gained two dozen seats. The makeup of the new assembly meant that a coalition of the National Constitutionalists and the Party of Regions lacked enough seats to form a majority government. Grand Vizier Tewfik Pasha, the leader of the Party of Regions, subsequently resigned and the coalition agreed to submit Hussein Riza Pasha as their candidate for Grand Vizier. Riza, the leader of the more Ottoman-nationalist National Constitutionalists, was unpopular with many seperatists, but he was determined to build a majority.

Not enough independents agreed to support the coalition for a majority, so Riza approached the moderate Armenian nationalists for an agreement. Riza had gained a reputation in the assembly as a defender of Armenian minority rights and had the respect of many Armenian nationalists. He was thus able to secure a tenuous majority by promising increased investment and autonomy for Armenia. This guarantee was enormously controversial, but Riza was able to shepherd the Autonomy Laws through the assembly by allowing the Arab nationalists to convince themselves that they would also receive more local autonomy in exchange. Though many National Constitutionalist MAs broke the whip, the law was nonetheless passed, establishing an autonomous Armenian vilayet out of Erzerum, Van and parts of Diyarbakar.

Following this victory, which presented a surprising turn for the centralist National Constitutionalists, Riza pushed ahead with industrial development, which he outlined in the Continued Modernization Program white paper issued by his government in March 1924. Key to the CMP were the construction of new railways and motorways into central Anatolia, Arabia and the Caucasus, further investment into heavy industry, and heavy investment into the growing oil industry. These programs were implemented by the coalition, though without the support of the Arabs. However, tensions quickly grew. Control over the Mosul, Baghdad, and Basra oil fields was given to the Iraqi Turkmen, enriching them to the anger of the Arab locals. Mosul saw a massive wave of immigration as Anatolian Turks moved south in search of work at the oil derricks. Riza also targeted the “medieval” rural Arab society, and this endeavor came to a head with local resistance to modernization in July 1925, when Riza proposed a major overhaul of local government.

Earlier reforms in 1920 had introduced locally-elected provincial assemblies and directly-elected Sanjakbeys, allowing a swift concentration of local power into the hands of Arab elites. Riza’s program would strip away much of the authority held by the Sanjakbeys and local judges and cede it to the centrally appointed Wali, allowing the central government its greatest level of provincial supremacy yet. Riza’s appointment of aggressive modernizers to head the Aleppo, Mosul, and Hejaz provinces had produced intense gridlock with the traditionalist local elites, and the new reforms were widely seen as an effort to break the opposition. Hussein Talib Bey, the Wali of Hejaz, had a particularly acrimonious relationship with local elites, as the powerful Hashemite clan, the Sharifs of Mecca, were accustomed to a great deal of influence in provincial administration and bristled at Talib’s reforms. The Arab independents, many of whom came from these powerful local families, were furious. They had assumed that Armenian autonomy presaged Arab devolution, and denounced Riza in the strongest terms.

Despite the opposition of the independents, the math was with Riza’s coalition, and his provincial reforms were narrowly approved by the assembly on August 25th, 1925. Days later, Wali Talib Bey declared that Hejazis were no longer exempt from military service, and that the wealthy elites of Mecca and Medina would be taxed in order to finance the subsidies given to the local poor. When Sharif Ali attempted to block this, the Wali overruled him and threatened to deploy the military garrison to enforce the decrees. Negotiations broke down as the Wali, fully supported by Riza’s government, refused to back down. Finally, on October 9th, Talib Bey ordered the Sharif’s arrest. The Sharif’s personal guard resisted, and after a brief battle, the Ottoman garrison was forced to retreat. Sharif Ali declared himself King of Hejaz and called on his subjects to revolt against the Ottomans. Joined by other powerful families, the revolt swiftly grew. Mecca quickly became untenable for the garrison, and so the Wali and his forces fled to Medina, but banditry along the railway forced his further withdrawal to Tabuk…

…Egypt was not idle during the Ottoman unrest. With Britain distracted by the violence in Ireland and the first rumblings of labor unrest, their influence in Cairo had ebbed. This conveniently coincided with the Arabian troubles and the 1918 ascension of Khedive Tewfik II. The new Khedive was an Egyptian and Arab nationalist and plotted to exploit Ottoman divisions and seize the Syrian provinces of Damascus, Jerusalem, and Beirut. He envisioned an Egyptian-dominated “Islamic community” in Arabia, and sought to defeat both the Ottomans and Hashemites. Together with his allies in the parliament [1], the Khedive established connections with local powerbrokers like the al-Wahsh family [2] in Aleppo and the al-Atrash in Damascus and made tentative contact with the embittered Hashemites. Cairo watched the Hashemite rebellion with close interest, and Egyptian agents encouraged local rebellions in Greater Syria.

Two months after the beginning of the Hejazi revolt, Hussein al-Husayni, the Mufti of Jerusalem, called for rebellion against Ottoman authority, and thousands of locals answered his call, attacking Ottoman garrisons. Jerusalem quickly fell to the rebels, threatening Amman and the Hejaz railway. By this point, Riza was still reluctant to fully deploy the military, worried about alienating the rest of the Empire’s Arabian citizens and that such use of force would show weakness. He was finally convinced that garrisons alone could not quell the rebels when the Druze rose up and when a coalition of powerful Damascene families led by the al-Bakris instigated an insurrection. However, by the time Riza ordered a general mobilization, much of Syria was plagued by rebellion, and Damascus had descended into anarchy. The potential that Damascus could fall forced Talib Bey to abandon the Hejaz and flee north, lest the railroad fall, and his army become encircled.

Unfortunately, the Ottoman response came too late to prevent the crisis from deepening. Khedive Tewfik II declared war on March 12th, 1926, framing his intervention as a defense of the Arab people. Using modern British equipment and tactics, the Egyptian army was, while smaller than the Ottoman force, highly professional. The initial advance was overwhelmingly successful, with Egyptian troops linking up with the Mufti’s rebels in Jerusalem and capturing Amman within two months. Meanwhile, emboldened rebels successfully seized Damascus, trapping the exiled Wali and his haggard forces in southern Syria. The Egyptian intervention came as a surprise to Riza’s government, and the overall strategy shifted to secure northern Syria and Iraq first and then take the fight south. However, this plan became complicated by uprisings in Baghdad and Basra. Local families instigated rioting and open rebellion, creating a second front for the Ottomans to fight. While the mobilizing Ottoman armies focused on securing Aleppo and the valuable oil fields of Mosul, as well as vital railroads, the rebels coalesced into semi-organized armies.

As the Egyptians advanced towards Damascus, Lebanon collapsed into its own civil war, as Christians fearful of the Islamist Arabism espoused by Egypt sided with the Ottomans and the Arabs fought them. The Hashemites quickly found that Egypt was not intervening to support Sharif Ali’s Arab Kingdom, and the two armies fought several skirmishes. The Rashidi Emirate, allied with the Ottomans, invaded Hejaz to crush the separatist Hashemites, which distracted them from the still-extant, still-plotting House of Saud, who themselves were plotting to take advantage of the chaos in Iraq…”

-From A POCKET HISTORY OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE by Yvette Leventhal, published 2015

“The landmark Supreme Court ruling in Norris v. Lee, that black men were full citizens of the United States, was longstanding judicial precedence, having been codified into the constitution as the sixteenth amendment. The sixteenth amendment, like Norris, guaranteed birthright citizenship, explicitly including the right to vote. However, the sixteenth amendment was only intended to apply to the children of white immigrants, and the court system frequently ruled against black plaintiffs who had been barred from voting, while whites experienced little difference. The main methods that southern states employed to eliminate black suffrage were bogus literacy tests and poll taxes.

In 1924, a black man named James Covey sued the state of Virginia with the help of CANR after he was turned away at the polls because he could not afford their poll tax. He argued that the poll tax was “explicitly targeted” at black would-be voters due to the ancestry clause and was therefore unconstitutional. CANR lawyers claimed that restricting the poll tax to the descendants of slaves (by exempting those eligible to vote prior to abolition and their descendants) both deprived citizens of their rights, while also violating the Norris argument that slaves were also citizens, despite being held in bondage. Virginia’s lawyers sidestepped the racial issue entirely, instead arguing that there were no constitutional or judicial restrictions on the poll tax.

Local courts sided with the Virginia government, while the largely Whig-nominated federal appeals courts ruled that the poll tax was unconstitutional. The Supreme Court agreed to hear the case for their 1925 docket, giving the issue a national platform for the first time. In a 6-3 ruling, the court found that a poll tax was not an “egregious or undue” imposition, and therefore did not violate the constitution. In a word, the poll tax was legal, and James Covey had to pay it if he wanted to try and vote [3].

The effects of Covey v. Virginia were felt almost immediately. Missouri, under a Democratic trifecta, rammed through a statewide poll tax that was almost immediately opposed by the egalitarian Jackson County government (dominated by the city of Independence). By this point, the city was dominated by the Mormon community, and had a large, wealthy, and politically-engaged black population. The imposition of a poll tax outraged the city, and Mayor Edward Tanner and County Executive Sidney Stark announced that the local governments would not collect a poll tax from eligible voters. This sparked its own political crisis, as Governor David Cooke ordered the State Marshall Service to oversee the tax collection and sued the local governments to force them into submission. Independence citizens openly harassed State Marshalls throughout the 1926 campaign, and police were publicly instructed to impede collection of the poll tax.

Fighting over the Missouri poll tax ultimately resulted in a decisive defeat for the Democratic party, as voters were upset that Governor Cooke and his party were more focused on beating Independence into submission than reducing unemployment or repairing the state’s dilapidated roads and making them usable by automobiles. Turnout in Independence reached all-time highs as Marshalls were kept away from most polling stations by jeering crowds and police escorts, while there were street brawls in a few precincts. The new Whig majority in Jefferson City immediately voted to repeal the poll tax, and threatened to stall budgetary proceedings until Cooke signed the repeal bill. In the aftermath of the Poll Tax Crisis, the Whigs lost support among rural Missourians, while Governor Cooke was denied renomination by his party in 1928 due to his signing, however reluctant, of the repeal law. It was a rare victory for civil rights in that era, and even as terrorism and unrest plagued the rest of the south during the 1960s [4], Missouri remained an island of peace…”

-From WHITE MAN’S NATION: AMERICA 1881-1973 by Kenneth Thurman, published 2003

[1] TTL, there is a more minor Egyptian Revolution that produces a weak parliament, dominated by an alternate version of the Wafd Party.

[2] Aka the Assads.

[3] He’d still probably get beaten savagely, or worse, by racist mobs for attempting to vote.

[4] Spoilers, I guess.

“As the Ottoman Empire continued to modernize and focus on Rumelia, a sense of Arabian alienation grew in the Empire’s southern territories. Oil was discovered in the years following the Treaty of London, but this only heightened the alienation. In the 1923 elections, the decentralist Party of Regions suffered a landslide defeat as Arab constituencies voted in large numbers for local independents, while their National Constitutionalist coalition partners 0nly gained two dozen seats. The makeup of the new assembly meant that a coalition of the National Constitutionalists and the Party of Regions lacked enough seats to form a majority government. Grand Vizier Tewfik Pasha, the leader of the Party of Regions, subsequently resigned and the coalition agreed to submit Hussein Riza Pasha as their candidate for Grand Vizier. Riza, the leader of the more Ottoman-nationalist National Constitutionalists, was unpopular with many seperatists, but he was determined to build a majority.

Not enough independents agreed to support the coalition for a majority, so Riza approached the moderate Armenian nationalists for an agreement. Riza had gained a reputation in the assembly as a defender of Armenian minority rights and had the respect of many Armenian nationalists. He was thus able to secure a tenuous majority by promising increased investment and autonomy for Armenia. This guarantee was enormously controversial, but Riza was able to shepherd the Autonomy Laws through the assembly by allowing the Arab nationalists to convince themselves that they would also receive more local autonomy in exchange. Though many National Constitutionalist MAs broke the whip, the law was nonetheless passed, establishing an autonomous Armenian vilayet out of Erzerum, Van and parts of Diyarbakar.

Following this victory, which presented a surprising turn for the centralist National Constitutionalists, Riza pushed ahead with industrial development, which he outlined in the Continued Modernization Program white paper issued by his government in March 1924. Key to the CMP were the construction of new railways and motorways into central Anatolia, Arabia and the Caucasus, further investment into heavy industry, and heavy investment into the growing oil industry. These programs were implemented by the coalition, though without the support of the Arabs. However, tensions quickly grew. Control over the Mosul, Baghdad, and Basra oil fields was given to the Iraqi Turkmen, enriching them to the anger of the Arab locals. Mosul saw a massive wave of immigration as Anatolian Turks moved south in search of work at the oil derricks. Riza also targeted the “medieval” rural Arab society, and this endeavor came to a head with local resistance to modernization in July 1925, when Riza proposed a major overhaul of local government.

Earlier reforms in 1920 had introduced locally-elected provincial assemblies and directly-elected Sanjakbeys, allowing a swift concentration of local power into the hands of Arab elites. Riza’s program would strip away much of the authority held by the Sanjakbeys and local judges and cede it to the centrally appointed Wali, allowing the central government its greatest level of provincial supremacy yet. Riza’s appointment of aggressive modernizers to head the Aleppo, Mosul, and Hejaz provinces had produced intense gridlock with the traditionalist local elites, and the new reforms were widely seen as an effort to break the opposition. Hussein Talib Bey, the Wali of Hejaz, had a particularly acrimonious relationship with local elites, as the powerful Hashemite clan, the Sharifs of Mecca, were accustomed to a great deal of influence in provincial administration and bristled at Talib’s reforms. The Arab independents, many of whom came from these powerful local families, were furious. They had assumed that Armenian autonomy presaged Arab devolution, and denounced Riza in the strongest terms.

Despite the opposition of the independents, the math was with Riza’s coalition, and his provincial reforms were narrowly approved by the assembly on August 25th, 1925. Days later, Wali Talib Bey declared that Hejazis were no longer exempt from military service, and that the wealthy elites of Mecca and Medina would be taxed in order to finance the subsidies given to the local poor. When Sharif Ali attempted to block this, the Wali overruled him and threatened to deploy the military garrison to enforce the decrees. Negotiations broke down as the Wali, fully supported by Riza’s government, refused to back down. Finally, on October 9th, Talib Bey ordered the Sharif’s arrest. The Sharif’s personal guard resisted, and after a brief battle, the Ottoman garrison was forced to retreat. Sharif Ali declared himself King of Hejaz and called on his subjects to revolt against the Ottomans. Joined by other powerful families, the revolt swiftly grew. Mecca quickly became untenable for the garrison, and so the Wali and his forces fled to Medina, but banditry along the railway forced his further withdrawal to Tabuk…

…Egypt was not idle during the Ottoman unrest. With Britain distracted by the violence in Ireland and the first rumblings of labor unrest, their influence in Cairo had ebbed. This conveniently coincided with the Arabian troubles and the 1918 ascension of Khedive Tewfik II. The new Khedive was an Egyptian and Arab nationalist and plotted to exploit Ottoman divisions and seize the Syrian provinces of Damascus, Jerusalem, and Beirut. He envisioned an Egyptian-dominated “Islamic community” in Arabia, and sought to defeat both the Ottomans and Hashemites. Together with his allies in the parliament [1], the Khedive established connections with local powerbrokers like the al-Wahsh family [2] in Aleppo and the al-Atrash in Damascus and made tentative contact with the embittered Hashemites. Cairo watched the Hashemite rebellion with close interest, and Egyptian agents encouraged local rebellions in Greater Syria.

Two months after the beginning of the Hejazi revolt, Hussein al-Husayni, the Mufti of Jerusalem, called for rebellion against Ottoman authority, and thousands of locals answered his call, attacking Ottoman garrisons. Jerusalem quickly fell to the rebels, threatening Amman and the Hejaz railway. By this point, Riza was still reluctant to fully deploy the military, worried about alienating the rest of the Empire’s Arabian citizens and that such use of force would show weakness. He was finally convinced that garrisons alone could not quell the rebels when the Druze rose up and when a coalition of powerful Damascene families led by the al-Bakris instigated an insurrection. However, by the time Riza ordered a general mobilization, much of Syria was plagued by rebellion, and Damascus had descended into anarchy. The potential that Damascus could fall forced Talib Bey to abandon the Hejaz and flee north, lest the railroad fall, and his army become encircled.

Unfortunately, the Ottoman response came too late to prevent the crisis from deepening. Khedive Tewfik II declared war on March 12th, 1926, framing his intervention as a defense of the Arab people. Using modern British equipment and tactics, the Egyptian army was, while smaller than the Ottoman force, highly professional. The initial advance was overwhelmingly successful, with Egyptian troops linking up with the Mufti’s rebels in Jerusalem and capturing Amman within two months. Meanwhile, emboldened rebels successfully seized Damascus, trapping the exiled Wali and his haggard forces in southern Syria. The Egyptian intervention came as a surprise to Riza’s government, and the overall strategy shifted to secure northern Syria and Iraq first and then take the fight south. However, this plan became complicated by uprisings in Baghdad and Basra. Local families instigated rioting and open rebellion, creating a second front for the Ottomans to fight. While the mobilizing Ottoman armies focused on securing Aleppo and the valuable oil fields of Mosul, as well as vital railroads, the rebels coalesced into semi-organized armies.

As the Egyptians advanced towards Damascus, Lebanon collapsed into its own civil war, as Christians fearful of the Islamist Arabism espoused by Egypt sided with the Ottomans and the Arabs fought them. The Hashemites quickly found that Egypt was not intervening to support Sharif Ali’s Arab Kingdom, and the two armies fought several skirmishes. The Rashidi Emirate, allied with the Ottomans, invaded Hejaz to crush the separatist Hashemites, which distracted them from the still-extant, still-plotting House of Saud, who themselves were plotting to take advantage of the chaos in Iraq…”

-From A POCKET HISTORY OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE by Yvette Leventhal, published 2015

“The landmark Supreme Court ruling in Norris v. Lee, that black men were full citizens of the United States, was longstanding judicial precedence, having been codified into the constitution as the sixteenth amendment. The sixteenth amendment, like Norris, guaranteed birthright citizenship, explicitly including the right to vote. However, the sixteenth amendment was only intended to apply to the children of white immigrants, and the court system frequently ruled against black plaintiffs who had been barred from voting, while whites experienced little difference. The main methods that southern states employed to eliminate black suffrage were bogus literacy tests and poll taxes.

In 1924, a black man named James Covey sued the state of Virginia with the help of CANR after he was turned away at the polls because he could not afford their poll tax. He argued that the poll tax was “explicitly targeted” at black would-be voters due to the ancestry clause and was therefore unconstitutional. CANR lawyers claimed that restricting the poll tax to the descendants of slaves (by exempting those eligible to vote prior to abolition and their descendants) both deprived citizens of their rights, while also violating the Norris argument that slaves were also citizens, despite being held in bondage. Virginia’s lawyers sidestepped the racial issue entirely, instead arguing that there were no constitutional or judicial restrictions on the poll tax.

Local courts sided with the Virginia government, while the largely Whig-nominated federal appeals courts ruled that the poll tax was unconstitutional. The Supreme Court agreed to hear the case for their 1925 docket, giving the issue a national platform for the first time. In a 6-3 ruling, the court found that a poll tax was not an “egregious or undue” imposition, and therefore did not violate the constitution. In a word, the poll tax was legal, and James Covey had to pay it if he wanted to try and vote [3].

The effects of Covey v. Virginia were felt almost immediately. Missouri, under a Democratic trifecta, rammed through a statewide poll tax that was almost immediately opposed by the egalitarian Jackson County government (dominated by the city of Independence). By this point, the city was dominated by the Mormon community, and had a large, wealthy, and politically-engaged black population. The imposition of a poll tax outraged the city, and Mayor Edward Tanner and County Executive Sidney Stark announced that the local governments would not collect a poll tax from eligible voters. This sparked its own political crisis, as Governor David Cooke ordered the State Marshall Service to oversee the tax collection and sued the local governments to force them into submission. Independence citizens openly harassed State Marshalls throughout the 1926 campaign, and police were publicly instructed to impede collection of the poll tax.

Fighting over the Missouri poll tax ultimately resulted in a decisive defeat for the Democratic party, as voters were upset that Governor Cooke and his party were more focused on beating Independence into submission than reducing unemployment or repairing the state’s dilapidated roads and making them usable by automobiles. Turnout in Independence reached all-time highs as Marshalls were kept away from most polling stations by jeering crowds and police escorts, while there were street brawls in a few precincts. The new Whig majority in Jefferson City immediately voted to repeal the poll tax, and threatened to stall budgetary proceedings until Cooke signed the repeal bill. In the aftermath of the Poll Tax Crisis, the Whigs lost support among rural Missourians, while Governor Cooke was denied renomination by his party in 1928 due to his signing, however reluctant, of the repeal law. It was a rare victory for civil rights in that era, and even as terrorism and unrest plagued the rest of the south during the 1960s [4], Missouri remained an island of peace…”

-From WHITE MAN’S NATION: AMERICA 1881-1973 by Kenneth Thurman, published 2003

[1] TTL, there is a more minor Egyptian Revolution that produces a weak parliament, dominated by an alternate version of the Wafd Party.

[2] Aka the Assads.

[3] He’d still probably get beaten savagely, or worse, by racist mobs for attempting to vote.

[4] Spoilers, I guess.

Last edited:

90. Change, For Better or Worse

90. Change, For Better or Worse

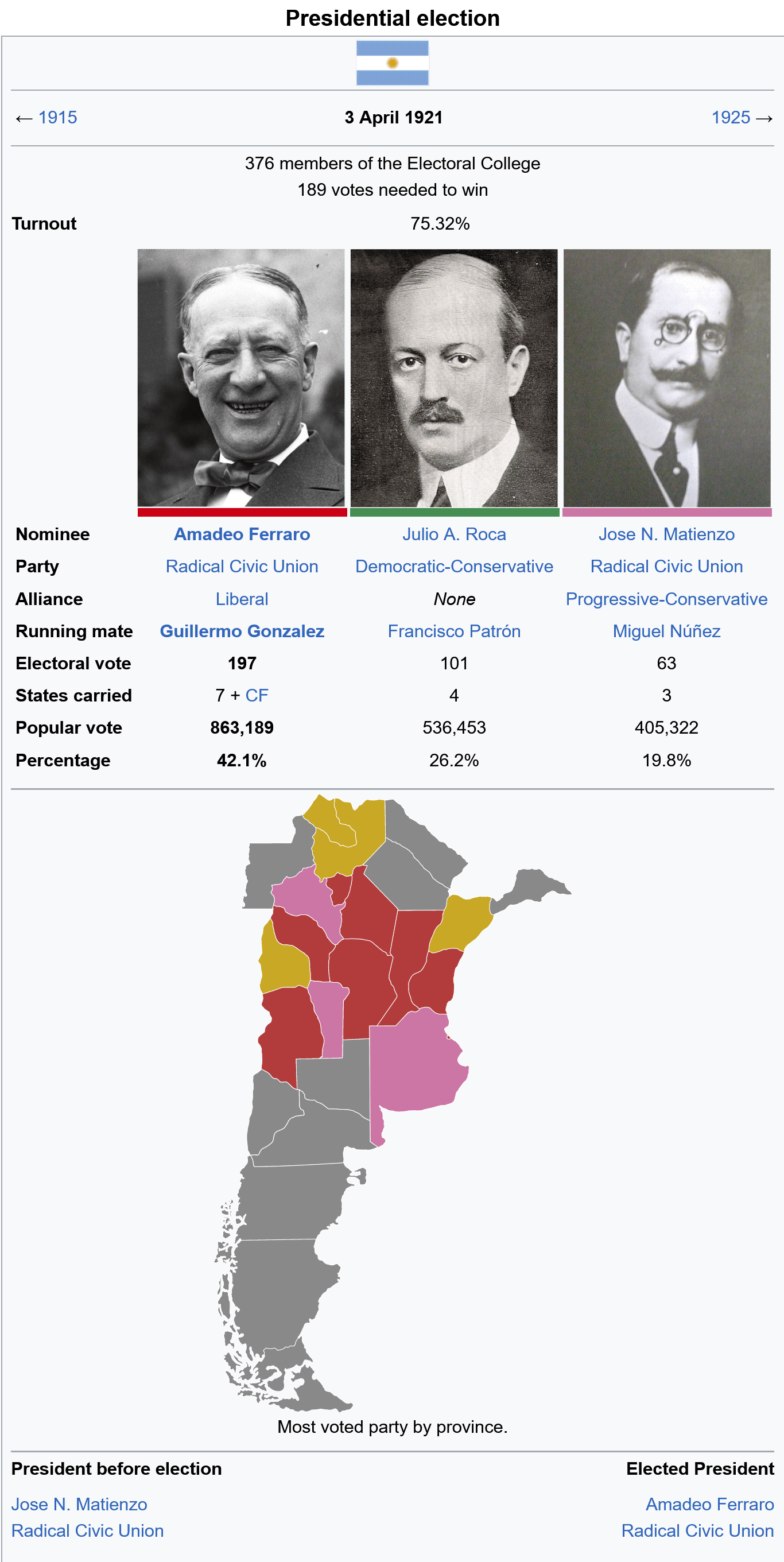

“Under President Matienzo, the Radical Civic Union was in a state of chaos. The party was bitterly divided between the ascendant Ferrarista faction, led by the eponymous Amadeo Ferraro, the popular governor of Santa Fe, and the centrists, which had no clear leader [1]. While internal divisions were nothing new, the level of infighting and instability was unprecedented, especially ahead of the 1921 general election. Amid a deep recession, Matienzo was the only prominent centrist willing to stand as a candidate against Amadeo Ferraro, and so the RCU convention was to decide between the two. Inevitably, the party split over the nomination, with the official convention selecting Governor Ferraro and a splinter coalition of the centrist RCU and the rump Progressive-Conservatives nominating President Matienzo.

The Democratic-Conservatives nominated Senator Julio A. Roca, the son of a popular former president and a war hero in his own right, with party founder Francisco Patrón as his running mate. Fiercely conservative, the DCs attacked both the RCU-PC ticket and the Ferraristas as anti-Catholic and at fault for the depression. Matienzo tried to campaign in person, but he was paranoid about assassination and mostly spoke to large, carefully controlled crowds while Ferraro traveled by car and shook as many hands as possible on his campaign. He promised a “Nuevo Acuerdo,” or New Deal, of public works projects, new welfare programs, and constitutional reforms. Key among these proposals were a national highway system, investment into modern industries such as chemicals, and the abolition of the electoral college in favor of a two-round system.

The campaign was marred by serious national unrest. Coal miners went on strike four weeks before the election, and Patriotic League members conducted marches and rallies to frighten voters. On March 27th, just days before the election, a Patriotic League supporter attempted to assassinate Governor Ferraro at a campaign appearance in Cordoba, but he was tackled and beaten by the crowd. Amid high tensions, the country went to the polls on April 3rd. While it was widely assumed that the race would be close, Ferraro prevailed over Roca, his closest rival, by nearly 2o percentage points. President Matienzo finished an embarrassing third, with less than 20 percent of the vote. Ferraro also won an absolute majority of the electoral college, with 197 out of 376. He declared victory in front of a crowd of a thousand in Rosario before traveling to Buenos Aires for his inauguration that October…

Ferraro moved quickly to stabilize the economy, ordering the temporary closure of banks to prevent further collapse in the sector. He targeted the slums of Buenos Aires and Cordoba for public works projects and proposed an overhaul of national labor law. Labor reform was unpopular with business owners due to the poor overall economy, but Ferraro maintained that inflationary spending was the only way to reinvigorate the economy. Paired with the labor law, which increased injury pensions, was a new trade reciprocity agreement with the United Kingdom’s William Brodrick’s Tory government, which expanded Argentina’s trade opportunities.

Slum clearances proved popular, as the new housing was safer, larger, and cheaper than before, and their construction created much-needed work. Ferraro also pursued a plan to develop the interior, authorizing new roads, hydroelectric dams, and subsidized oil wells, mines and factories across western Argentina. Among these new factories were several new state-funded chemical plants, as Ferraro sought to diversify the Argentine economy [2]. These measures, all undertaken in his first year as President, greatly enhanced his popularity, aided by Ferraro’s habit of regularly touring the country to visit public works projects and speak with voters directly. While the economy was slow to recover, even the initial signs of recovery were a source of hope for the Argentine people, and Ferraro’s policies were a source of inspiration for politicians in the United States, chief among them Howard Cameron…”

-From ARGENTINA: A MODERN HISTORY by Jessica Harvey, published 2011

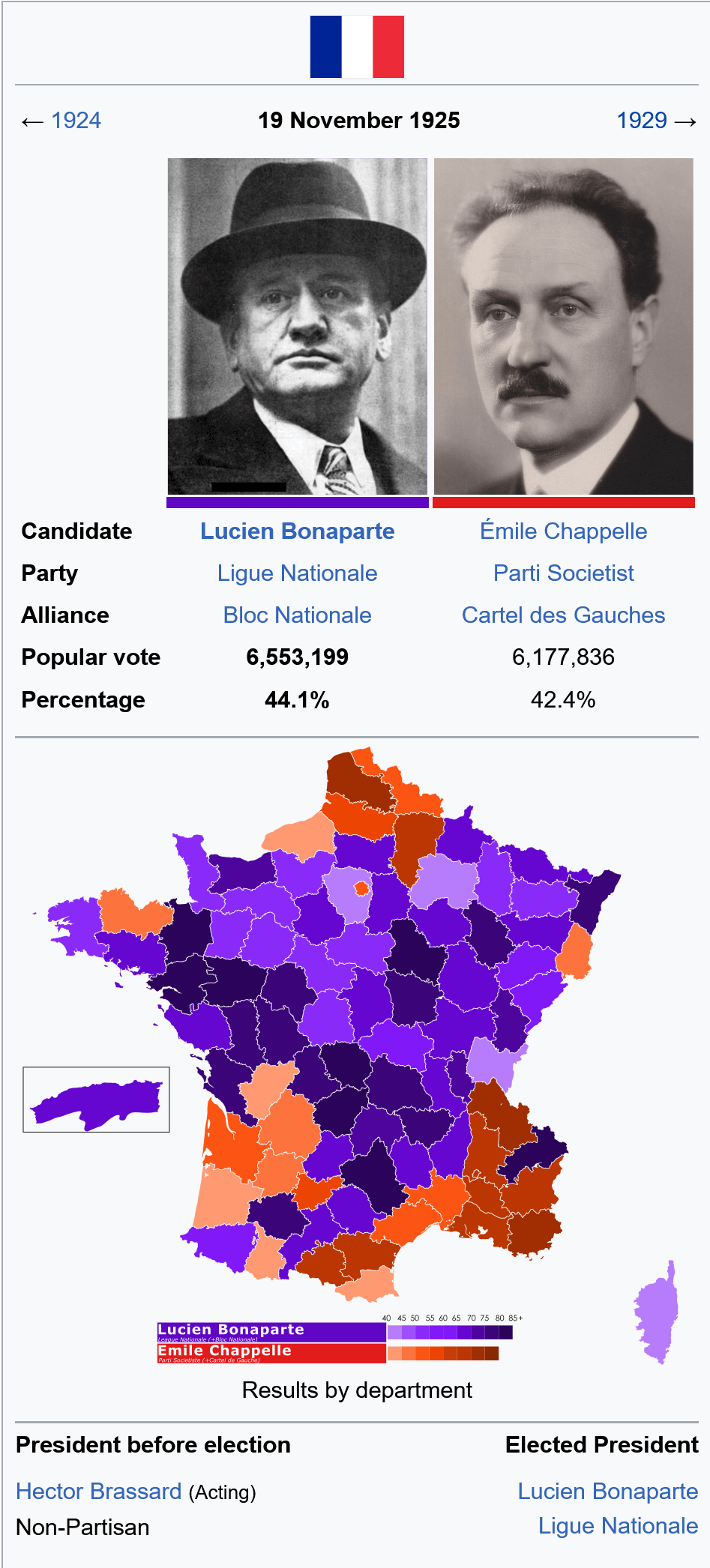

“France in the 1920s was in a state of despair and malaise. Trade unions went on strike nearly every other week, inflation was rampant, and the unemployment rate was at an all-time high. After President Deschanel won the 1920 election via the National Assembly despite losing the popular vote, the Second Republic’s institutions became discredited, and polarization grew. While the left consolidated behind the Broad Front of the Societists and Solidarists, the right wing took an ugly turn. At the center of the new direction of the right was the National League, a paramilitary force consisting of unemployed Great War veterans. The League was bankrolled by Lucien Bonaparte, a descendant of Emperor Napoleon who had, until the war, been a low-profile businessman and municipal politician.

Caught in the center of this deepening crisis was President Deschanel’s National Bloc. Deschanel struggled to stabilize the economy, as the country was saddled with heavy debt from the war. Spending cuts and pro-business policies angered the unions, who retaliated with waves of strikes and public demonstrations. Criminal gangs proliferated in city centers as the unemployed turned towards less legal ways of earning a living. Even when Deschanel tried to unite the country, he failed, as exemplified by his successful push to grant full citizenship to literate, educated Algerian Muslims, as well as Muslim veterans of the French military and those who renounced Islamic law.

This citizenship law enraged the Algerian settlers, who renounced the National Bloc and joined Bonaparte’s National League. Ahead of the 1924 election, Deschanel was deeply unpopular, but was both determined to run again and confident that the extremism of his opponents would earn him a victory. His efforts to amend the constitution to permanently allow for consecutive reelections only deepened public hatred towards him. However, the Assembly was swayed by Deschanel’s demagogic warnings of Societist dictatorship and granted Deschanel special permission to run for a second consecutive term. News of this exception provoked renewed protests and rioting, which were suppressed by the NL paramilitaries as Bonaparte called for a “restoration of order.”

Nevertheless, France went to the polls in January 1924, with the Societists once again confident of victory. The campaign had been brutal, with instances of paramilitary violence against Societist operatives met with union militias guarding rallies, and much furious rhetoric from the NL about the dangers of the Societists. Unfortunately, once again no candidate won a majority of the vote, with the Societists’ Chappelle leading with 45% of the vote, followed distantly by Deschanel with 27%, then Bonaparte with 26% and a variety of independents, including Senator, and former general, Hector Brassard. Once again, the National Assembly was to elect the president. Bonaparte, unwilling to fully support the hated Deschanel, allowed a free vote for the small cadre of NL legislators, while once again the embattled center-right bloc united behind Deschanel. This time, the president failed to win in the first round of voting, forcing a new round of negotiations. Eventually, enough NL support was obtained to secure Deschanel’s second term.

His successful reelection only heightened tensions. Already Deschanel was seen as illegitimate, but for him to be elected a second time despite winning less than one third of the vote was nothing short of outraging for even moderate Frenchmen. Despite the hostile national atmosphere, in August 1925 Deschanel decided that he would visit a new automobile factory in Lyon to tout the first stirrings of recovery. Deschanel was determined to meet with the people, and insisted on riding in an open-topped car, with heavily-armed guards, of course. After an icy reception from the workers at the factory, the motorcade was driving through the city center when two men threw small packages into the President’s car. They exploded immediately, killing Deschanel, his wife, and several of their guards. The vice president was sworn in from his hospital bed, which he was confined to after suffering a major heart attack. He died just days later, leaving France without a clear president [3].

As Lucien Bonaparte took to the radio waves to blame the assassination on the Societists (although later investigations would reveal that the men were actually anarchists who acted alone), the Assembly met to elect an interim president. The Societists, reluctant to use the assassination to push for Chappelle’s election, abstained from the vote while the National Bloc elected Hector Brassard as acting-president. Brassard immediately declared martial law, announcing in a speech broadcast over the radio that “there are insurrectionists hiding in the shadows, and we must take strict measures to root them out.” A national curfew was imposed, and the new presidential elections were postponed for two months. These measures were incredibly unpopular, prompting further protests and riots. Bonaparte, running once again for president, denounced the strikers in his speeches and called for “harmony of purpose” between labor and capital.

The Societists once again fielded Emile Chappelle as their candidate, while the National Bloc collapsed. Many businessmen and rural, religious groups endorsed the National League, as Bonaparte was seen as an honest businessman, a patriot, and a conservative. In the end, much of the old Democratic Alliance fell in behind Bonaparte’s League, while the rest of Deschanel’s National Bloc supported acting-president Brassard. Nicholas Barthou, the former wartime president, mounted an independent “unity” bid, but only succeeded in uniting the country against him. Throughout the campaign, France remained under martial law and NL paramilitaries marched through the streets. While the Societists protested that Bonaparte’s men were harassing and intimidating their supporters, the conservative Brassard refused to act, accusing Chappelle of fomenting discord.

Election day was November 19th, 1925. The day was marred by violence outside of polling stations, with Bonaparte’s final campaign speech urging the people to “defend our country from the Societist scourge by any means necessary,” and there was even a failed attempt to shoot Bonaparte, which he eagerly blamed on a Societist agent. Newspapers warned against Bonaparte, describing him as a demagogue, a dictator, and opined that to elect him President would mean the end of the Republic. Turnout was at its highest point since before the war, but the final numbers spelled the end of the Second Republic. Lucien Bonaparte narrowly led with 6,553,199 votes, or 44.1%. In a major surprise, Emile Chappelle led the Societists to a close second, 6,177,836 votes and 42.4.%. Chappelle immediately cried foul, arguing that National League intimidation and violence at polling stations in working-class areas had depressed turnout. Other Societist figures claimed that Bonaparte had stuffed the ballot boxes in rural precincts to juice his numbers [4].

While the Societists were the largest single party in the Assembly since 1923, they were once again unable to rally outside support, while the National League could call upon the members of the center-right bloc. As NL paramilitaries paraded around the Assembly building and Bonaparte addressed them as “heroes of the Republic,” inside the deliberations began under immense pressure. Some NL members crowded into the public viewing spaces, holding banners and wearing NL uniforms to further intimidate the Assembly. On the first ballot, with support from the dead husk of the National Bloc, Lucien Bonaparte was narrowly elected as President of France. He took the oath of office to the cheers of onlooking NL militiamen and gave a speech vowing to protect the Republic “from all her enemies, without and within,” but his oath to “remain faithful to the democratic Republic” would soon be violated as France, and much of Europe, entered the Lost Decade…”

-From THE REPUBLIC: A HISTORY OF MODERN FRANCE by Eric Young, published 2003

“Facing another election in 1926 and having only won the last two by the thinnest of margins, Howard Cameron was desperate to build a more secure political machine. One of his largest critics was the newspaper publisher Michael Danforth, who employed emotionally charged language and obviously slanted viewpoints to excite readers and influence public opinion. Danforth commanded a large audience nationwide, but his ownership of the Detroit Monitor, as well as the most-read newspapers in Lansing and Grand Rapids, gave him a uniquely outsized influence over voters in Michigan. He had endorsed the Democratic tickets in both 1922 and 1924, and had run frequent editorials criticizing Cameron as a radical who engaged in class warfare.

Seeking to consolidate public support, Cameron arranged to meet with Danforth in early 1925, just days after being sworn in for a second term. By all accounts the meeting was incredibly productive, and the two men would up having three more formal meetings within the month, eventually developing a strong friendship. Having begun his governorship with Danforth as an avowed rival, the meetings began a long alliance between the two as Danforth agreed to shift the tone of his papers [5]. Shortly after the Cameron-Danforth summit, the Monitor began to change its tone. Rather than focus on the various minor slip-ups of Cameron and his government, the Monitor began zeroing in on corruption and gaffes of Democratic politicians, and even praised some of Cameron’s policies, such as his construction of new roads and passage of an expanded workplace injury compensation scheme.

Cameron’s relationship with Danforth has deeply influenced the relationship between the American government, especially the Whig Party, and the press, but at the time, Cameron was widely criticized by the Democrats for his closeness to the press. This was denounced as “collusion” by John Ives, who was once again challenging Cameron for governor. The 1926 elections were expected to favor the Democrats, as the ec0nomy had recovered from stagnation and President Delaney was very popular. Further, Ives was very critical of Cameron’s frequent fighting with the legislature, claiming that he used authoritarian tactics to railroad his reforms through the process. However, Ives’s campaign was dealt a severe blow in August of 1926, when the Monitor shocked the Democrats by endorsing Cameron for Governor.

Though the Danforth media empire had grown steadily more supportive of Cameron, the papers still took a generally pro-Democratic editorial position, and so most assumed that the Monitor would endorse Ives once again. With the Monitor running pro-Cameron stories and attacking Ives in the final months of the campaign, Ives’s early advantage evaporated. The unfavorable media environment, combined with Cameron’s tireless campaigning and canvassing network of Wide Awakes, pointed towards a third term for Governor Cameron. On election day, Cameron was reelected by a comfortable margin of 53.5% to 44.2%, and his coalition of solidarist Whigs won an outright majority in the legislature. While the Democrats easily held the Senate with no losses and won 241 seats in the House, a loss of just 18 seats, their failure to defeat the embattled and vulnerable Cameron, and indeed his expanded margin of victory, was an embarrassment for the party. But for Howard Cameron, now elected to his third term as Governor, the 1926 election was a great victory, and he finally began to turn his eye towards the presidency.”

-From THE DETROIT LION by John Philip Yates, published 2012

[1] As mentioned in chapter 79.

[2] Funds were also drawn from the Uruguayan reconstruction firm, while Uruguay was left mired in economic crisis due to Argentine neglect.

[3] The constitution of the Second Republic left few contingencies for sudden crises.

[4] Later investigations under the post-Bonapartist government have revealed that between rampant ballot-stuffing in rural areas and widespread voter intimidation in the cities, the Bonapartists should have won somewhere between 35-37 percent of the vote, and the Societists somewhere between 46-51 percent.

[5] Get ready for British-style tabloid rags in TTL’s America. Sure the Tribune and the Advocate are good papers, but they don’t have fun graphics, invective-filled editorials, and models on page 3.

“Under President Matienzo, the Radical Civic Union was in a state of chaos. The party was bitterly divided between the ascendant Ferrarista faction, led by the eponymous Amadeo Ferraro, the popular governor of Santa Fe, and the centrists, which had no clear leader [1]. While internal divisions were nothing new, the level of infighting and instability was unprecedented, especially ahead of the 1921 general election. Amid a deep recession, Matienzo was the only prominent centrist willing to stand as a candidate against Amadeo Ferraro, and so the RCU convention was to decide between the two. Inevitably, the party split over the nomination, with the official convention selecting Governor Ferraro and a splinter coalition of the centrist RCU and the rump Progressive-Conservatives nominating President Matienzo.

The Democratic-Conservatives nominated Senator Julio A. Roca, the son of a popular former president and a war hero in his own right, with party founder Francisco Patrón as his running mate. Fiercely conservative, the DCs attacked both the RCU-PC ticket and the Ferraristas as anti-Catholic and at fault for the depression. Matienzo tried to campaign in person, but he was paranoid about assassination and mostly spoke to large, carefully controlled crowds while Ferraro traveled by car and shook as many hands as possible on his campaign. He promised a “Nuevo Acuerdo,” or New Deal, of public works projects, new welfare programs, and constitutional reforms. Key among these proposals were a national highway system, investment into modern industries such as chemicals, and the abolition of the electoral college in favor of a two-round system.

The campaign was marred by serious national unrest. Coal miners went on strike four weeks before the election, and Patriotic League members conducted marches and rallies to frighten voters. On March 27th, just days before the election, a Patriotic League supporter attempted to assassinate Governor Ferraro at a campaign appearance in Cordoba, but he was tackled and beaten by the crowd. Amid high tensions, the country went to the polls on April 3rd. While it was widely assumed that the race would be close, Ferraro prevailed over Roca, his closest rival, by nearly 2o percentage points. President Matienzo finished an embarrassing third, with less than 20 percent of the vote. Ferraro also won an absolute majority of the electoral college, with 197 out of 376. He declared victory in front of a crowd of a thousand in Rosario before traveling to Buenos Aires for his inauguration that October…

Ferraro moved quickly to stabilize the economy, ordering the temporary closure of banks to prevent further collapse in the sector. He targeted the slums of Buenos Aires and Cordoba for public works projects and proposed an overhaul of national labor law. Labor reform was unpopular with business owners due to the poor overall economy, but Ferraro maintained that inflationary spending was the only way to reinvigorate the economy. Paired with the labor law, which increased injury pensions, was a new trade reciprocity agreement with the United Kingdom’s William Brodrick’s Tory government, which expanded Argentina’s trade opportunities.

Slum clearances proved popular, as the new housing was safer, larger, and cheaper than before, and their construction created much-needed work. Ferraro also pursued a plan to develop the interior, authorizing new roads, hydroelectric dams, and subsidized oil wells, mines and factories across western Argentina. Among these new factories were several new state-funded chemical plants, as Ferraro sought to diversify the Argentine economy [2]. These measures, all undertaken in his first year as President, greatly enhanced his popularity, aided by Ferraro’s habit of regularly touring the country to visit public works projects and speak with voters directly. While the economy was slow to recover, even the initial signs of recovery were a source of hope for the Argentine people, and Ferraro’s policies were a source of inspiration for politicians in the United States, chief among them Howard Cameron…”

-From ARGENTINA: A MODERN HISTORY by Jessica Harvey, published 2011

“France in the 1920s was in a state of despair and malaise. Trade unions went on strike nearly every other week, inflation was rampant, and the unemployment rate was at an all-time high. After President Deschanel won the 1920 election via the National Assembly despite losing the popular vote, the Second Republic’s institutions became discredited, and polarization grew. While the left consolidated behind the Broad Front of the Societists and Solidarists, the right wing took an ugly turn. At the center of the new direction of the right was the National League, a paramilitary force consisting of unemployed Great War veterans. The League was bankrolled by Lucien Bonaparte, a descendant of Emperor Napoleon who had, until the war, been a low-profile businessman and municipal politician.

Caught in the center of this deepening crisis was President Deschanel’s National Bloc. Deschanel struggled to stabilize the economy, as the country was saddled with heavy debt from the war. Spending cuts and pro-business policies angered the unions, who retaliated with waves of strikes and public demonstrations. Criminal gangs proliferated in city centers as the unemployed turned towards less legal ways of earning a living. Even when Deschanel tried to unite the country, he failed, as exemplified by his successful push to grant full citizenship to literate, educated Algerian Muslims, as well as Muslim veterans of the French military and those who renounced Islamic law.

This citizenship law enraged the Algerian settlers, who renounced the National Bloc and joined Bonaparte’s National League. Ahead of the 1924 election, Deschanel was deeply unpopular, but was both determined to run again and confident that the extremism of his opponents would earn him a victory. His efforts to amend the constitution to permanently allow for consecutive reelections only deepened public hatred towards him. However, the Assembly was swayed by Deschanel’s demagogic warnings of Societist dictatorship and granted Deschanel special permission to run for a second consecutive term. News of this exception provoked renewed protests and rioting, which were suppressed by the NL paramilitaries as Bonaparte called for a “restoration of order.”

Nevertheless, France went to the polls in January 1924, with the Societists once again confident of victory. The campaign had been brutal, with instances of paramilitary violence against Societist operatives met with union militias guarding rallies, and much furious rhetoric from the NL about the dangers of the Societists. Unfortunately, once again no candidate won a majority of the vote, with the Societists’ Chappelle leading with 45% of the vote, followed distantly by Deschanel with 27%, then Bonaparte with 26% and a variety of independents, including Senator, and former general, Hector Brassard. Once again, the National Assembly was to elect the president. Bonaparte, unwilling to fully support the hated Deschanel, allowed a free vote for the small cadre of NL legislators, while once again the embattled center-right bloc united behind Deschanel. This time, the president failed to win in the first round of voting, forcing a new round of negotiations. Eventually, enough NL support was obtained to secure Deschanel’s second term.

His successful reelection only heightened tensions. Already Deschanel was seen as illegitimate, but for him to be elected a second time despite winning less than one third of the vote was nothing short of outraging for even moderate Frenchmen. Despite the hostile national atmosphere, in August 1925 Deschanel decided that he would visit a new automobile factory in Lyon to tout the first stirrings of recovery. Deschanel was determined to meet with the people, and insisted on riding in an open-topped car, with heavily-armed guards, of course. After an icy reception from the workers at the factory, the motorcade was driving through the city center when two men threw small packages into the President’s car. They exploded immediately, killing Deschanel, his wife, and several of their guards. The vice president was sworn in from his hospital bed, which he was confined to after suffering a major heart attack. He died just days later, leaving France without a clear president [3].

As Lucien Bonaparte took to the radio waves to blame the assassination on the Societists (although later investigations would reveal that the men were actually anarchists who acted alone), the Assembly met to elect an interim president. The Societists, reluctant to use the assassination to push for Chappelle’s election, abstained from the vote while the National Bloc elected Hector Brassard as acting-president. Brassard immediately declared martial law, announcing in a speech broadcast over the radio that “there are insurrectionists hiding in the shadows, and we must take strict measures to root them out.” A national curfew was imposed, and the new presidential elections were postponed for two months. These measures were incredibly unpopular, prompting further protests and riots. Bonaparte, running once again for president, denounced the strikers in his speeches and called for “harmony of purpose” between labor and capital.

The Societists once again fielded Emile Chappelle as their candidate, while the National Bloc collapsed. Many businessmen and rural, religious groups endorsed the National League, as Bonaparte was seen as an honest businessman, a patriot, and a conservative. In the end, much of the old Democratic Alliance fell in behind Bonaparte’s League, while the rest of Deschanel’s National Bloc supported acting-president Brassard. Nicholas Barthou, the former wartime president, mounted an independent “unity” bid, but only succeeded in uniting the country against him. Throughout the campaign, France remained under martial law and NL paramilitaries marched through the streets. While the Societists protested that Bonaparte’s men were harassing and intimidating their supporters, the conservative Brassard refused to act, accusing Chappelle of fomenting discord.

Election day was November 19th, 1925. The day was marred by violence outside of polling stations, with Bonaparte’s final campaign speech urging the people to “defend our country from the Societist scourge by any means necessary,” and there was even a failed attempt to shoot Bonaparte, which he eagerly blamed on a Societist agent. Newspapers warned against Bonaparte, describing him as a demagogue, a dictator, and opined that to elect him President would mean the end of the Republic. Turnout was at its highest point since before the war, but the final numbers spelled the end of the Second Republic. Lucien Bonaparte narrowly led with 6,553,199 votes, or 44.1%. In a major surprise, Emile Chappelle led the Societists to a close second, 6,177,836 votes and 42.4.%. Chappelle immediately cried foul, arguing that National League intimidation and violence at polling stations in working-class areas had depressed turnout. Other Societist figures claimed that Bonaparte had stuffed the ballot boxes in rural precincts to juice his numbers [4].

While the Societists were the largest single party in the Assembly since 1923, they were once again unable to rally outside support, while the National League could call upon the members of the center-right bloc. As NL paramilitaries paraded around the Assembly building and Bonaparte addressed them as “heroes of the Republic,” inside the deliberations began under immense pressure. Some NL members crowded into the public viewing spaces, holding banners and wearing NL uniforms to further intimidate the Assembly. On the first ballot, with support from the dead husk of the National Bloc, Lucien Bonaparte was narrowly elected as President of France. He took the oath of office to the cheers of onlooking NL militiamen and gave a speech vowing to protect the Republic “from all her enemies, without and within,” but his oath to “remain faithful to the democratic Republic” would soon be violated as France, and much of Europe, entered the Lost Decade…”

-From THE REPUBLIC: A HISTORY OF MODERN FRANCE by Eric Young, published 2003

“Facing another election in 1926 and having only won the last two by the thinnest of margins, Howard Cameron was desperate to build a more secure political machine. One of his largest critics was the newspaper publisher Michael Danforth, who employed emotionally charged language and obviously slanted viewpoints to excite readers and influence public opinion. Danforth commanded a large audience nationwide, but his ownership of the Detroit Monitor, as well as the most-read newspapers in Lansing and Grand Rapids, gave him a uniquely outsized influence over voters in Michigan. He had endorsed the Democratic tickets in both 1922 and 1924, and had run frequent editorials criticizing Cameron as a radical who engaged in class warfare.

Seeking to consolidate public support, Cameron arranged to meet with Danforth in early 1925, just days after being sworn in for a second term. By all accounts the meeting was incredibly productive, and the two men would up having three more formal meetings within the month, eventually developing a strong friendship. Having begun his governorship with Danforth as an avowed rival, the meetings began a long alliance between the two as Danforth agreed to shift the tone of his papers [5]. Shortly after the Cameron-Danforth summit, the Monitor began to change its tone. Rather than focus on the various minor slip-ups of Cameron and his government, the Monitor began zeroing in on corruption and gaffes of Democratic politicians, and even praised some of Cameron’s policies, such as his construction of new roads and passage of an expanded workplace injury compensation scheme.

Cameron’s relationship with Danforth has deeply influenced the relationship between the American government, especially the Whig Party, and the press, but at the time, Cameron was widely criticized by the Democrats for his closeness to the press. This was denounced as “collusion” by John Ives, who was once again challenging Cameron for governor. The 1926 elections were expected to favor the Democrats, as the ec0nomy had recovered from stagnation and President Delaney was very popular. Further, Ives was very critical of Cameron’s frequent fighting with the legislature, claiming that he used authoritarian tactics to railroad his reforms through the process. However, Ives’s campaign was dealt a severe blow in August of 1926, when the Monitor shocked the Democrats by endorsing Cameron for Governor.

Though the Danforth media empire had grown steadily more supportive of Cameron, the papers still took a generally pro-Democratic editorial position, and so most assumed that the Monitor would endorse Ives once again. With the Monitor running pro-Cameron stories and attacking Ives in the final months of the campaign, Ives’s early advantage evaporated. The unfavorable media environment, combined with Cameron’s tireless campaigning and canvassing network of Wide Awakes, pointed towards a third term for Governor Cameron. On election day, Cameron was reelected by a comfortable margin of 53.5% to 44.2%, and his coalition of solidarist Whigs won an outright majority in the legislature. While the Democrats easily held the Senate with no losses and won 241 seats in the House, a loss of just 18 seats, their failure to defeat the embattled and vulnerable Cameron, and indeed his expanded margin of victory, was an embarrassment for the party. But for Howard Cameron, now elected to his third term as Governor, the 1926 election was a great victory, and he finally began to turn his eye towards the presidency.”

-From THE DETROIT LION by John Philip Yates, published 2012

[1] As mentioned in chapter 79.

[2] Funds were also drawn from the Uruguayan reconstruction firm, while Uruguay was left mired in economic crisis due to Argentine neglect.

[3] The constitution of the Second Republic left few contingencies for sudden crises.

[4] Later investigations under the post-Bonapartist government have revealed that between rampant ballot-stuffing in rural areas and widespread voter intimidation in the cities, the Bonapartists should have won somewhere between 35-37 percent of the vote, and the Societists somewhere between 46-51 percent.

[5] Get ready for British-style tabloid rags in TTL’s America. Sure the Tribune and the Advocate are good papers, but they don’t have fun graphics, invective-filled editorials, and models on page 3.

Lol never thought of Cameron as a Gaullist, but I guess it fits. He's going places that's for sure, not all of them goodExcited to see what Michigan’s De Gaulle gets up to

That both parties kind of suck in different ways is what makes this very different yet familiar take on American history so good. Excited for more, glad you're finding time in your studies to keep this plugging along!Lol never thought of Cameron as a Gaullist, but I guess it fits. He's going places that's for sure, not all of them good

Thanks so much, glad you're enjoying it! Honestly the way I've written things I have no idea if I'd be a Democrat or a Whig TTLThat both parties kind of suck in different ways is what makes this very different yet familiar take on American history so good. Excited for more, glad you're finding time in your studies to keep this plugging along!

You gotta swing vote TTL, baby!Thanks so much, glad you're enjoying it! Honestly the way I've written things I have no idea if I'd be a Democrat or a Whig TTL

Hah I guess so, a pretty far cry from how I am OTL lolYou gotta swing vote TTL, baby!

I’d probably be a Whig - the unrepentant Dem racism is just a bit too much for me ITTL - but there’d be a lot to dislike about the heirs of Henry ClayThanks so much, glad you're enjoying it! Honestly the way I've written things I have no idea if I'd be a Democrat or a Whig TTL

Yah that's the big sticking point of the Dems TTL, they're this weird blend of classical-liberal party like LaREM or Republican Proposal with the Dixiecrats. TBH I'd most likely strongly lean Whig because of that, but down-ballot races would be more of a tough choice for meI’d probably be a Whig - the unrepentant Dem racism is just a bit too much for me ITTL - but there’d be a lot to dislike about the heirs of Henry Clay

The 1921 Argentine Presidential election and 1925 French Presidential election:

Lol is that Alfredo Smith 😅 well doneThe 1921 Argentine Presidential election and 1925 French Presidential election:

View attachment 823189View attachment 823190

Yeah,pretenders will be banned from politics, and the Third Republic will generally be more radical than its predecessor.Surely this Lucien Bonaparte guy would have never come to power if all royal pretenders were banned from running for any forms of elections or holding any forms of public service jobs. The Third Republic must put this clause into the new Constitution.

Indeed it is, I was waiting for someone to point that out lolLol is that Alfredo Smith 😅 well done

Share: