16. To Life

Chapter 16

On February 11, 2004, snowflakes drifted gently to earth, coating the National Mall in a blanket of powdery white. Across the river, in Arlington, an ambulance quickly made its way to the home of an important public figure, its lights flashing brightly through the wintry mix and its sirens echoing through neighborhoods. The paramedics arrived and put the septuagenarian onto a stretcher. He strained to sit up, coughing harshly and depositing mucus mixed with blood into his hand. He was wheezing severely. About three hours after he was wheeled into the ambulance, White House Chief of Staff Mike Murphy phoned the president, waking him up in the dead of night.

When he heard the news, the president groaned into the receiver – unsure why he was being woken up when so little information about the situation existed. He rolled over and went back to bed. He woke up around 6:30 that morning and trudged into the bathroom, showering and brushing his teeth, before joining his wife for breakfast.

“Have you seen this?” she asked, gesturing the remote toward the television. Katie Couric narrated the events in Arlington from the night before. “His condition remains unclear,” the anchor said ominously.

McCain nodded. “Mike called last night,” he told his wife.

Two days later, the news some had anticipated became official. The president was in the Oval Office meeting with Murphy and National Security Adviser William Ball. Mark Salter interrupted.

“Mr. President,” he said, “Chief Justice Rehnquist died about 30 minutes ago.”

The president nodded solemnly. “Alright,” he said. “Mark, you’re going to need to get whatever sonofabitch we nominate through the Senate. I want you to lead this process. Meet with the Counsel’s office and get a list of names. We’ll start going from there.”

Ball sat quietly – his meeting hijacked by breaking news. Salter nodded, taking notes on his hand as the president rattled off bits and pieces of the types of people he wanted on the list. He gave Salter only one specific name. “Make sure we vet Gonzales.”

“Alberto?”

“Yes. We should revisit the files from a few years ago and see what needs to be added.” Salter nodded, scribbling down the reminder. “And I need to call Rehnquist’s children.”

Across Pennsylvania Avenue, Senate Minority Whip Harry Reid called the caucus’ leader, Tom Daschle of South Dakota. “We can’t let McCain make this appointment.”

“Rehnquist?” Daschle asked, confused.

“Yes.”

“What do you mean?”

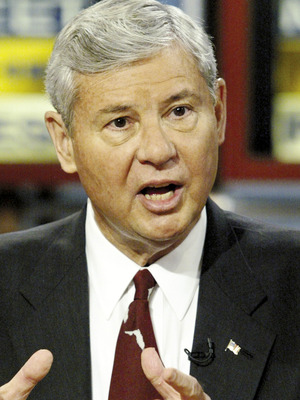

“Tom, we’re nine months away from a presidential election. Who knows what could happen? Whether it’s Kerry or Wellstone – we might have a Democratic president come January, and they could fill the seat. I think we can argue that this is an election year – no one’s ever appointed a justice, let alone a Chief Justice, during an election year – and that we should let the American people pick the next Chief Justice.”

“I don’t know, Harry. The Court has never animated the left the way it has the right.”

“This is an opportunity for us. If I were you, I would go out there right now, and I would say: Whoever wins in November can replace Rehnquist.”

“Jesus, Harry – the man’s body is still warm.”

“We can’t waste any time with this, or it won’t work.”

Daschle agreed to float the idea by others. His first call was to Ted Kennedy, the powerful Democrat from Massachusetts who had stopped the Bork nomination years earlier. He ran Reid’s idea by him. “I think it’s brilliant,” he said. “Let’s take our chances. Worst case scenario, McCain gets to fill it in his second term. We have the votes to filibuster a nomination,” Kennedy said. He brought Chris Dodd, his friend from Connecticut and the former presidential contender, to his side.

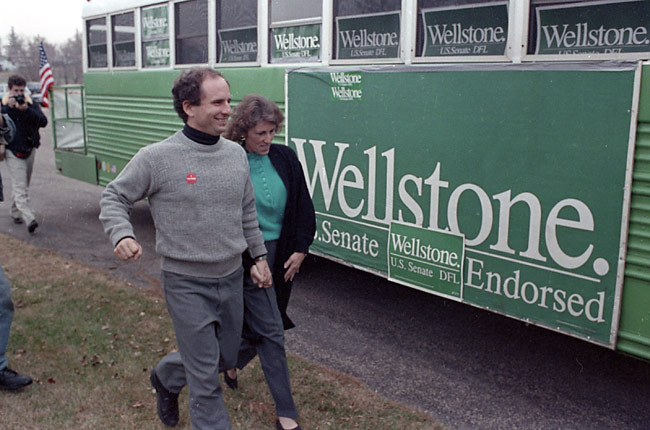

Senators Ted Kennedy and Harry Reid wanted to block any nominee to replace Chief Justice Rehnquist until after the 2004 presidential election.

Ironically, two of the most vocal opponents of the idea in the caucus were from the top presidential contenders. Neither Kerry nor Wellstone nor John Edwards wanted the Democrats to leave the seat open. Having the Supreme Court on the ballot in such a pronounced way only excited the Evangelical right – McCain’s weakest bloc. It was possible that they might have suppressed turnout in November because McCain had not been their strongest ally. If that were the case, it was possible for Democrats to pull off an upset. If Democrats kept the seat open, they would turn out in droves.

Other Democrats also opposed the idea. Recently elected moderates like Chet Edwards and Harold Ford, Jr., decried the norm-breaking behavior. Had any previous nomination been held open that long? They thought the idea was politically foolish. Others, like Hillary Clinton, opposed the idea because it was so brazenly political. “This is the kind of shit they’d have pulled against Bill,” she said to Daschle. “We’re better than they are, and we shouldn’t stoop to their level.”

About three hours after Rehnquist’s death became public, the rumors that Democrats would block McCain from filling the seat trickled into the mainstream conversation. And so, Daschle had to make a decision. He walked into the Senate press room and told reporters that while the caucus had “examined the precedent around an election-year appointment,” they had “no intention” of blindly filibustering any nominee to replace Rehnquist. The Senate Democrats were committed, he said, to their role of advise and consent. Should the president appoint an unqualified or unfit justice, they would do their part to prevent such a nominee from taking the bench. But they would not hold the seat open. And so the Daschle precedent was set: A president could appoint a Supreme Court Justice during an election year.

The entire idea of filibustering whatever nominee McCain chose, regardless of who it was, seemed bizarre to the White House, and Mike Murphy was in disbelief that Democrats had even considered the idea. The White House certainly hadn’t. With the rumors and drama laid aside, the White House conducted its review of candidates. In the meantime, the nation came together to bury one of the most influential Supreme Court Justices in history – and a champion of the modern conservative movement.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/64309995/328075.0.jpg)

The president's initial shortlist included Alice Moore Batchelder, Edith Brown Clement, Alberto Gonzales, and Michael McConnell (from left to right).

A list of 11 candidates was brought down to a final four: Alice Moore Batchelder, Edith Brown Clement, Alberto Gonzales, and Michael McConnell. The early favorite for the seat was Batchelder. The president was excited to name the first woman Chief Justice – which he believed would help cement his legacy. Those on his team who reviewed her opinions were impressed with her writing skills – and her opinions. Batchelder was a decidedly conservative jurist. She dissented in a landmark case that upheld affirmative action, took a restrictive view of the Commerce Clause, and in United States v. Chesney (1996) – a gun control case – she voted to invalidate a part of the Gun Control Act that had been upheld by 10 other circuit courts of appeal. In McCain’s mind, she was the strongest choice – both to cement support on the right and to gather popular support from the rest of the political spectrum. She was also Kellyanne Conway’s top choice. Conway believed that Democrats would be mum on their opposition to the first woman Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. She was wrong.

After Batchelder traveled to Washington to meet with the president, the story broke, and reporters began delving into her record. The Washington Post ran a front-page story about an issue they had previously covered – Batchelder had ruled in five lawsuits involving Wal-Mart and Bristol Myers Squibb – companies that her husband’s retirement account was heavily invested in. As a judge, she should have recused herself from those cases, she argued. In an interview on CNN, Senator Kennedy said that kind of conflict was “exactly the kind of thing” that would disqualify one of McCain’s appointees. Fearful of a difficult confirmation fight, the president and his team moved on.

Two of the people on McCain’s short list hailed from the Fifth Circuit Court, which was not usually a place from which presidents chose Supreme Court Justices. The first was Edith Brown Clement, whom the president had appointed in 2001. She was more ideologically nuanced than Gonzales, and some on the right feared what she meant when she told the Senate Judiciary Committee that the Supreme Court “has clearly held the right to privacy … includes the right to have an abortion.” Supporters of hers said that the statement was merely a statement of fact and not endorsement. Detractors worried that, if given the chance, she would not overturn Roe. There was little known about Brown, which raised the question that she may be another David Souter – whom President Bush had appointed only to realize he was more liberal leaning in his ideology. The Federalist Society had, however, endorsed her 2001 nomination.

Gonzales’ 2002 appointment was an attempt to mollify the Bush wing of the Party. Appointing him to the Supreme Court would be a more overtly political choice. He had served as Governor George W. Bush’s counsel in Austin before Bush appointed him to be Texas Secretary of State and then Associate Justice on the Texas Supreme Court. Like Clement, he had largely avoided controversial cases during his two years on the Bench, but while that would help Clement, it hurt Gonzales. Because so much of Gonzales’ tenure had been political, Democrats would be able to more easily pin him as an ideological selection. Additionally, he had one fewer year on the federal bench, and it would be easier to paint him as unqualified for the role.

Michael McConnell was appointed by McCain to serve on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit in 2001, and he was the preferred choice of judicial academia – having broad support from conservatives and liberals alike. He had argued before the Supreme Court and spent years as a law professor, researching, publishing, and editing many volumes of legal work. In 1996, he signed a statement supporting a Constitutional amendment to ban abortion, but he had not ruled on the issue since joining the bench. It was unclear whether he’d be willing to go back on judicial precedent. A sober individual, he did little to excite the president and did even less to excite Conway. He was, however, Salter’s preferred choice.

As the inner circle reviewed the final three names on the list, Conway decided to add a fourth: Antonin Scalia. Appointed to the Supreme Court by Ronald Reagan, Scalia was seen as the premiere conservative mind on the Bench. His nomination would excite the right and while the left would be opposed, the White House agreed he’d be confirmed with Democratic votes. At first, the suggestion was seen as a joke, but Murphy soon began to like the idea while Salter remained hesitant. The glaring issue with Scalia was his age. At 69 years old, it was doubtful that Scalia could serve long on the Court (which had become a key factor in appointments). “Does the guy have 15 years in him?” Murphy asked at one of their discussions.

The White House began to consider promoting Associate Justice Antonin Scalia to the position of Chief Justice.

“Fifteen?” Salter scoffed. “Does the guy even have 10?”

McCain, too, was worried about Scalia’s age. The nomination of a young Chief Justice who could set the direction and pace of the court for the next 20 years enticed McCain, who wanted to leave his mark on history. Murphy, however, started to change his mind on a Scalia nomination. The problem with the current list was that after eight years of Clinton nominations, the Bush appointees were too old, and the McCain appointees were too inexperienced. Nominating Scalia as a placeholder Chief Justice gave McCain the chance to replace him with one of these other candidates, who could serve as an Associate Justice and then replace Scalia at the center of the bench when Scalia was done serving. He was 69 years old, but he wasn’t seen as someone in failing health. It was conceivable that he could serve another 10-12 years, enough time for Clement, Gonzales, or McConnell to be his obvious successor. Or, that president could appoint one of McCain’s Court of Appeals nominees who would have fifteen years of experience by that point.

McCain’s biggest concern, however, was that it would be impossible to guarantee that Scalia was replaced by a Republican president. It was simply too big of a risk. McCain was stuck between three imperfect nominees: Clement, who would become the nation’s first woman Chief Justice, Gonzales, who would become the first Hispanic Chief Justice – or justice, for that matter, and McConnell, who, while not history-making, would likely encounter the least opposition from the left. The president met with all three and then made his decision.

At a Rose Garden ceremony on April 5, 2004, the president nominated Edith Brown Clement to serve as the Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. Quickly, Republican senators expressed their support for the nomination as “ground-breaking.” The Federalist Society, though cautious about her previous comments on choice, believed Clement was an “acceptable” choice, and the Democrats were largely quiet – praising the historical nature of McCain’s choice. The lack of a considerable paper trail left little to attack her on other than a perceived lack of qualification to serve as Chief Justice, but no Democrat wanted to be seen as accusing the first woman nominated for Chief Justice as being “unqualified.”

Her nomination hearings took place in June as the Court wrapped up its term. Poised and collected, Brown Clement answered numerous questions from the Judiciary Committee with the kind of evasiveness that had become typical of the process. There were no scandals or flashy dissents in her record – she was a safe pick because her paper record was so scarce. And so, in July of 2004, the Senate voted 96-4 to confirm her nomination to the Supreme Court. Senators Daniel Akaka of Hawaii, Daniel Inouye of Hawaii, Kennedy, and Reid voted against her nomination. Edith Brown Clement became the 17th person and the first woman to serve as Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court.

To Life

On February 11, 2004, snowflakes drifted gently to earth, coating the National Mall in a blanket of powdery white. Across the river, in Arlington, an ambulance quickly made its way to the home of an important public figure, its lights flashing brightly through the wintry mix and its sirens echoing through neighborhoods. The paramedics arrived and put the septuagenarian onto a stretcher. He strained to sit up, coughing harshly and depositing mucus mixed with blood into his hand. He was wheezing severely. About three hours after he was wheeled into the ambulance, White House Chief of Staff Mike Murphy phoned the president, waking him up in the dead of night.

When he heard the news, the president groaned into the receiver – unsure why he was being woken up when so little information about the situation existed. He rolled over and went back to bed. He woke up around 6:30 that morning and trudged into the bathroom, showering and brushing his teeth, before joining his wife for breakfast.

“Have you seen this?” she asked, gesturing the remote toward the television. Katie Couric narrated the events in Arlington from the night before. “His condition remains unclear,” the anchor said ominously.

McCain nodded. “Mike called last night,” he told his wife.

Two days later, the news some had anticipated became official. The president was in the Oval Office meeting with Murphy and National Security Adviser William Ball. Mark Salter interrupted.

“Mr. President,” he said, “Chief Justice Rehnquist died about 30 minutes ago.”

The president nodded solemnly. “Alright,” he said. “Mark, you’re going to need to get whatever sonofabitch we nominate through the Senate. I want you to lead this process. Meet with the Counsel’s office and get a list of names. We’ll start going from there.”

Ball sat quietly – his meeting hijacked by breaking news. Salter nodded, taking notes on his hand as the president rattled off bits and pieces of the types of people he wanted on the list. He gave Salter only one specific name. “Make sure we vet Gonzales.”

“Alberto?”

“Yes. We should revisit the files from a few years ago and see what needs to be added.” Salter nodded, scribbling down the reminder. “And I need to call Rehnquist’s children.”

Across Pennsylvania Avenue, Senate Minority Whip Harry Reid called the caucus’ leader, Tom Daschle of South Dakota. “We can’t let McCain make this appointment.”

“Rehnquist?” Daschle asked, confused.

“Yes.”

“What do you mean?”

“Tom, we’re nine months away from a presidential election. Who knows what could happen? Whether it’s Kerry or Wellstone – we might have a Democratic president come January, and they could fill the seat. I think we can argue that this is an election year – no one’s ever appointed a justice, let alone a Chief Justice, during an election year – and that we should let the American people pick the next Chief Justice.”

“I don’t know, Harry. The Court has never animated the left the way it has the right.”

“This is an opportunity for us. If I were you, I would go out there right now, and I would say: Whoever wins in November can replace Rehnquist.”

“Jesus, Harry – the man’s body is still warm.”

“We can’t waste any time with this, or it won’t work.”

Daschle agreed to float the idea by others. His first call was to Ted Kennedy, the powerful Democrat from Massachusetts who had stopped the Bork nomination years earlier. He ran Reid’s idea by him. “I think it’s brilliant,” he said. “Let’s take our chances. Worst case scenario, McCain gets to fill it in his second term. We have the votes to filibuster a nomination,” Kennedy said. He brought Chris Dodd, his friend from Connecticut and the former presidential contender, to his side.

Senators Ted Kennedy and Harry Reid wanted to block any nominee to replace Chief Justice Rehnquist until after the 2004 presidential election.

Ironically, two of the most vocal opponents of the idea in the caucus were from the top presidential contenders. Neither Kerry nor Wellstone nor John Edwards wanted the Democrats to leave the seat open. Having the Supreme Court on the ballot in such a pronounced way only excited the Evangelical right – McCain’s weakest bloc. It was possible that they might have suppressed turnout in November because McCain had not been their strongest ally. If that were the case, it was possible for Democrats to pull off an upset. If Democrats kept the seat open, they would turn out in droves.

Other Democrats also opposed the idea. Recently elected moderates like Chet Edwards and Harold Ford, Jr., decried the norm-breaking behavior. Had any previous nomination been held open that long? They thought the idea was politically foolish. Others, like Hillary Clinton, opposed the idea because it was so brazenly political. “This is the kind of shit they’d have pulled against Bill,” she said to Daschle. “We’re better than they are, and we shouldn’t stoop to their level.”

About three hours after Rehnquist’s death became public, the rumors that Democrats would block McCain from filling the seat trickled into the mainstream conversation. And so, Daschle had to make a decision. He walked into the Senate press room and told reporters that while the caucus had “examined the precedent around an election-year appointment,” they had “no intention” of blindly filibustering any nominee to replace Rehnquist. The Senate Democrats were committed, he said, to their role of advise and consent. Should the president appoint an unqualified or unfit justice, they would do their part to prevent such a nominee from taking the bench. But they would not hold the seat open. And so the Daschle precedent was set: A president could appoint a Supreme Court Justice during an election year.

The entire idea of filibustering whatever nominee McCain chose, regardless of who it was, seemed bizarre to the White House, and Mike Murphy was in disbelief that Democrats had even considered the idea. The White House certainly hadn’t. With the rumors and drama laid aside, the White House conducted its review of candidates. In the meantime, the nation came together to bury one of the most influential Supreme Court Justices in history – and a champion of the modern conservative movement.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/64309995/328075.0.jpg)

The president's initial shortlist included Alice Moore Batchelder, Edith Brown Clement, Alberto Gonzales, and Michael McConnell (from left to right).

A list of 11 candidates was brought down to a final four: Alice Moore Batchelder, Edith Brown Clement, Alberto Gonzales, and Michael McConnell. The early favorite for the seat was Batchelder. The president was excited to name the first woman Chief Justice – which he believed would help cement his legacy. Those on his team who reviewed her opinions were impressed with her writing skills – and her opinions. Batchelder was a decidedly conservative jurist. She dissented in a landmark case that upheld affirmative action, took a restrictive view of the Commerce Clause, and in United States v. Chesney (1996) – a gun control case – she voted to invalidate a part of the Gun Control Act that had been upheld by 10 other circuit courts of appeal. In McCain’s mind, she was the strongest choice – both to cement support on the right and to gather popular support from the rest of the political spectrum. She was also Kellyanne Conway’s top choice. Conway believed that Democrats would be mum on their opposition to the first woman Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. She was wrong.

After Batchelder traveled to Washington to meet with the president, the story broke, and reporters began delving into her record. The Washington Post ran a front-page story about an issue they had previously covered – Batchelder had ruled in five lawsuits involving Wal-Mart and Bristol Myers Squibb – companies that her husband’s retirement account was heavily invested in. As a judge, she should have recused herself from those cases, she argued. In an interview on CNN, Senator Kennedy said that kind of conflict was “exactly the kind of thing” that would disqualify one of McCain’s appointees. Fearful of a difficult confirmation fight, the president and his team moved on.

Two of the people on McCain’s short list hailed from the Fifth Circuit Court, which was not usually a place from which presidents chose Supreme Court Justices. The first was Edith Brown Clement, whom the president had appointed in 2001. She was more ideologically nuanced than Gonzales, and some on the right feared what she meant when she told the Senate Judiciary Committee that the Supreme Court “has clearly held the right to privacy … includes the right to have an abortion.” Supporters of hers said that the statement was merely a statement of fact and not endorsement. Detractors worried that, if given the chance, she would not overturn Roe. There was little known about Brown, which raised the question that she may be another David Souter – whom President Bush had appointed only to realize he was more liberal leaning in his ideology. The Federalist Society had, however, endorsed her 2001 nomination.

Gonzales’ 2002 appointment was an attempt to mollify the Bush wing of the Party. Appointing him to the Supreme Court would be a more overtly political choice. He had served as Governor George W. Bush’s counsel in Austin before Bush appointed him to be Texas Secretary of State and then Associate Justice on the Texas Supreme Court. Like Clement, he had largely avoided controversial cases during his two years on the Bench, but while that would help Clement, it hurt Gonzales. Because so much of Gonzales’ tenure had been political, Democrats would be able to more easily pin him as an ideological selection. Additionally, he had one fewer year on the federal bench, and it would be easier to paint him as unqualified for the role.

Michael McConnell was appointed by McCain to serve on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 10th Circuit in 2001, and he was the preferred choice of judicial academia – having broad support from conservatives and liberals alike. He had argued before the Supreme Court and spent years as a law professor, researching, publishing, and editing many volumes of legal work. In 1996, he signed a statement supporting a Constitutional amendment to ban abortion, but he had not ruled on the issue since joining the bench. It was unclear whether he’d be willing to go back on judicial precedent. A sober individual, he did little to excite the president and did even less to excite Conway. He was, however, Salter’s preferred choice.

As the inner circle reviewed the final three names on the list, Conway decided to add a fourth: Antonin Scalia. Appointed to the Supreme Court by Ronald Reagan, Scalia was seen as the premiere conservative mind on the Bench. His nomination would excite the right and while the left would be opposed, the White House agreed he’d be confirmed with Democratic votes. At first, the suggestion was seen as a joke, but Murphy soon began to like the idea while Salter remained hesitant. The glaring issue with Scalia was his age. At 69 years old, it was doubtful that Scalia could serve long on the Court (which had become a key factor in appointments). “Does the guy have 15 years in him?” Murphy asked at one of their discussions.

The White House began to consider promoting Associate Justice Antonin Scalia to the position of Chief Justice.

“Fifteen?” Salter scoffed. “Does the guy even have 10?”

McCain, too, was worried about Scalia’s age. The nomination of a young Chief Justice who could set the direction and pace of the court for the next 20 years enticed McCain, who wanted to leave his mark on history. Murphy, however, started to change his mind on a Scalia nomination. The problem with the current list was that after eight years of Clinton nominations, the Bush appointees were too old, and the McCain appointees were too inexperienced. Nominating Scalia as a placeholder Chief Justice gave McCain the chance to replace him with one of these other candidates, who could serve as an Associate Justice and then replace Scalia at the center of the bench when Scalia was done serving. He was 69 years old, but he wasn’t seen as someone in failing health. It was conceivable that he could serve another 10-12 years, enough time for Clement, Gonzales, or McConnell to be his obvious successor. Or, that president could appoint one of McCain’s Court of Appeals nominees who would have fifteen years of experience by that point.

McCain’s biggest concern, however, was that it would be impossible to guarantee that Scalia was replaced by a Republican president. It was simply too big of a risk. McCain was stuck between three imperfect nominees: Clement, who would become the nation’s first woman Chief Justice, Gonzales, who would become the first Hispanic Chief Justice – or justice, for that matter, and McConnell, who, while not history-making, would likely encounter the least opposition from the left. The president met with all three and then made his decision.

At a Rose Garden ceremony on April 5, 2004, the president nominated Edith Brown Clement to serve as the Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. Quickly, Republican senators expressed their support for the nomination as “ground-breaking.” The Federalist Society, though cautious about her previous comments on choice, believed Clement was an “acceptable” choice, and the Democrats were largely quiet – praising the historical nature of McCain’s choice. The lack of a considerable paper trail left little to attack her on other than a perceived lack of qualification to serve as Chief Justice, but no Democrat wanted to be seen as accusing the first woman nominated for Chief Justice as being “unqualified.”

Her nomination hearings took place in June as the Court wrapped up its term. Poised and collected, Brown Clement answered numerous questions from the Judiciary Committee with the kind of evasiveness that had become typical of the process. There were no scandals or flashy dissents in her record – she was a safe pick because her paper record was so scarce. And so, in July of 2004, the Senate voted 96-4 to confirm her nomination to the Supreme Court. Senators Daniel Akaka of Hawaii, Daniel Inouye of Hawaii, Kennedy, and Reid voted against her nomination. Edith Brown Clement became the 17th person and the first woman to serve as Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court.

Last edited: