I didn't mind. It was pretty sweet too.Sorry to do something so heavy for my first return post :/

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Sand and Steel: The Story of the Modern Middle East (TL)

- Thread starter JSilvy

- Start date

Sorry to do something so heavy for my first return post :/

Nah, it’s okay, I liked it. It was worth the wait glad to see you back.

Then again, General Naguib is no Azula...King Farouk is certainly no Michael Corleone!

The Sons of Lions.

4 January 1966, 11:00 AM - Arabian National Cemetery, Damascus, UAS

His father was dead. His mother was dead. And his parents’ legacy was in his hands.

These were the thoughts that ran through the mind of Sultan Ghazi I, the new Sultan of the UAS. The coronation ceremony, however, had not yet taken place. That wouldn’t happen until his parents’ bodies was in the ground.

The ceremony was packed. Hundreds of people from all across the Sultanate were present, from Al-Iskenderun to Oman. The Emirs of Abu Dhabi, Dubai, and East Mutasalih were all conversing with one another. Members of Parliament from different parties gathered around to talk with one another. Prime Minister Ar-Rubai was in the crowd, who appeared to be conversing with Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir and the other Israelis accompanying her who had also been invited to the ceremony.

However, there was one Israeli visiter, standing by himself, who stood apart from the rest whom the new Sultan recognized immediately. Ben Gurion, the retired Israeli Prime Minister, who now spent most of his days on a desert commune in the south of his country, had made an appearance.

Ghazi was not the only person who recognized the short elderly man. As Ben Gurion stood there, he was approached by another young Arab man.

“Mr. Ben Gurion,” he said. “It is wonderful to see you.”

“Colonel Assad,” he responded. “I haven’t seen you since your father passed. How have you been?”

“I’m still in the military,” he responded proudly. “I’m a general now.”

“A general at 35,” Ben Gurion said. “You know back in my day, and man of your talents would have already been a general for years by now. I guess that’s peacetime for you.”

“Well let’s hope we remain in peacetime,” Assad joked, “but with everything going on in Africa right now, who’s to say?”

“Let’s pray to god that we don’t have another war,” Ben Gurion said. “Who knows how much two nuclear powers could devastate each other.”

There was a moment’s pause, and then Ben Gurion held his head down in reflection.

“You know, I was quite close with the Sultan,” Ben Gurion said. “I remember hosting them in Jerusalem during the war.”

“I know,” said Hafez. “I was there. I remember hearing your conversations. I remember how you spoke, how whenever one of you would lose hope, you would remind each other of what we were fighting for. You would talk about the values of liberty and equality and justice for your peoples, and how you would do anything to defend it. It’s what kept me going when my father was overseas for years. You two were like father’s to me.”

“Well,” said Ben Gurion, “I guess it takes the son of a lion to took after the son of a lion.”*

Assad paused for a moment.

“I’m thankful for the time that I have with my children,” he said. “Bushra and Bassel are the light of my life. It’s just hard to talk about now with what happened recently.”

“Is everything alright?” Ben Gurion asked, seeing the young man tear up.

“I had another child on the eleventh of September,” he said. “He was really sick and he died after a month. There was nothing the doctors could do but give him medicine to make the horrible pain go away.”

“I’m so sorry. I had no idea.”

“We had named him Bashar. I pray every night that his sleep is peaceful.”

“Death comes for us all,” Ben Gurion said. “There’s very little you can do. That’s why all we can do is hope to live life to its fullest.”

“You know I also remember Ghazi. He was also like a father, but much younger. I remember Faisal II following me around always wanting to play with me.”

“I do too,” Ben Gurion said. “Ghazi is not his father, but I have faith in the country’s future under his reign.”

Hafez listened to the proceedings. He watched as the casket was lowered. He saw Ghazi stand over the grave weeping. All had gone silent. Then Ghazi turned towards Hafez. For a moment, the two men made eye contact. Then the Sultan, swallowing his sorrow and holding his head high, elegantly spoke.

“My friends, as we are gathered today, let us not mourn a loss, but rather celebrate life, the life of a man who led us through our darkest times and into our brightest. However, a celebration of life is more than just a celebration of legacy. To me, Faisal was not just a Sultan or founder or a hero, but a father, a man with a big heart who loved those who were close to him. He was a man who cared for his family and do anything for us, just as he would do anything for our nation. He struggled through both World Wars so that today we could all live in peace, and now, we all do live in peace, and therefore my father can finally be at peace.”

And peace there was. No one could have known that the end of the decade would bring said peace to an end.

____________________________________

*The name “Ben Gurion”, a name adopted by David ben Gurion, means “Son of a Lion” with “ben” meaning “son” and the name “Gurion” meaning “young lion”. “Assad”, the name initially adopted by Ali-Sulayman al-Assad, is Arabic for “lion”. In this way, Both David ben Gurion and Hafez al-Assad are names that, in their respective languages, refer to them being the sons of lions.

His father was dead. His mother was dead. And his parents’ legacy was in his hands.

These were the thoughts that ran through the mind of Sultan Ghazi I, the new Sultan of the UAS. The coronation ceremony, however, had not yet taken place. That wouldn’t happen until his parents’ bodies was in the ground.

The ceremony was packed. Hundreds of people from all across the Sultanate were present, from Al-Iskenderun to Oman. The Emirs of Abu Dhabi, Dubai, and East Mutasalih were all conversing with one another. Members of Parliament from different parties gathered around to talk with one another. Prime Minister Ar-Rubai was in the crowd, who appeared to be conversing with Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir and the other Israelis accompanying her who had also been invited to the ceremony.

However, there was one Israeli visiter, standing by himself, who stood apart from the rest whom the new Sultan recognized immediately. Ben Gurion, the retired Israeli Prime Minister, who now spent most of his days on a desert commune in the south of his country, had made an appearance.

Ghazi was not the only person who recognized the short elderly man. As Ben Gurion stood there, he was approached by another young Arab man.

“Mr. Ben Gurion,” he said. “It is wonderful to see you.”

“Colonel Assad,” he responded. “I haven’t seen you since your father passed. How have you been?”

“I’m still in the military,” he responded proudly. “I’m a general now.”

“A general at 35,” Ben Gurion said. “You know back in my day, and man of your talents would have already been a general for years by now. I guess that’s peacetime for you.”

“Well let’s hope we remain in peacetime,” Assad joked, “but with everything going on in Africa right now, who’s to say?”

“Let’s pray to god that we don’t have another war,” Ben Gurion said. “Who knows how much two nuclear powers could devastate each other.”

There was a moment’s pause, and then Ben Gurion held his head down in reflection.

“You know, I was quite close with the Sultan,” Ben Gurion said. “I remember hosting them in Jerusalem during the war.”

“I know,” said Hafez. “I was there. I remember hearing your conversations. I remember how you spoke, how whenever one of you would lose hope, you would remind each other of what we were fighting for. You would talk about the values of liberty and equality and justice for your peoples, and how you would do anything to defend it. It’s what kept me going when my father was overseas for years. You two were like father’s to me.”

“Well,” said Ben Gurion, “I guess it takes the son of a lion to took after the son of a lion.”*

Assad paused for a moment.

“I’m thankful for the time that I have with my children,” he said. “Bushra and Bassel are the light of my life. It’s just hard to talk about now with what happened recently.”

“Is everything alright?” Ben Gurion asked, seeing the young man tear up.

“I had another child on the eleventh of September,” he said. “He was really sick and he died after a month. There was nothing the doctors could do but give him medicine to make the horrible pain go away.”

“I’m so sorry. I had no idea.”

“We had named him Bashar. I pray every night that his sleep is peaceful.”

“Death comes for us all,” Ben Gurion said. “There’s very little you can do. That’s why all we can do is hope to live life to its fullest.”

“You know I also remember Ghazi. He was also like a father, but much younger. I remember Faisal II following me around always wanting to play with me.”

“I do too,” Ben Gurion said. “Ghazi is not his father, but I have faith in the country’s future under his reign.”

Hafez listened to the proceedings. He watched as the casket was lowered. He saw Ghazi stand over the grave weeping. All had gone silent. Then Ghazi turned towards Hafez. For a moment, the two men made eye contact. Then the Sultan, swallowing his sorrow and holding his head high, elegantly spoke.

“My friends, as we are gathered today, let us not mourn a loss, but rather celebrate life, the life of a man who led us through our darkest times and into our brightest. However, a celebration of life is more than just a celebration of legacy. To me, Faisal was not just a Sultan or founder or a hero, but a father, a man with a big heart who loved those who were close to him. He was a man who cared for his family and do anything for us, just as he would do anything for our nation. He struggled through both World Wars so that today we could all live in peace, and now, we all do live in peace, and therefore my father can finally be at peace.”

And peace there was. No one could have known that the end of the decade would bring said peace to an end.

____________________________________

*The name “Ben Gurion”, a name adopted by David ben Gurion, means “Son of a Lion” with “ben” meaning “son” and the name “Gurion” meaning “young lion”. “Assad”, the name initially adopted by Ali-Sulayman al-Assad, is Arabic for “lion”. In this way, Both David ben Gurion and Hafez al-Assad are names that, in their respective languages, refer to them being the sons of lions.

And peace there was. No one could have known that the end of the decade would bring said peace to an end.

Uh oh ... problems ahead.

Good chapter

Idi Amin attempting assassination on Golda Meir?We will now be taking bets on how the peace is gonna get broken.

Last edited:

Bookmark1995

Banned

Idi Amin attempting another assassination on Golda Meir?

Can't wait to see where ol'Scottish king fits.

Same, maybe Amin is a military commander in the East African Federation (if it gets created)?Can't wait to see where ol'Scottish king fits.

Not gonna lie my plans for him are a bit more vanilla to otl than that but I do have an important alternate use for him in that position for this tl.Same, maybe Amin is a military commander in the East African Federation (if it gets created)?

I patiently await your use of him.Not gonna lie my plans for him are a bit more vanilla to otl than that but I do have an important alternate use for him in that position for this tl.

I fully intend to make good use of him.I patiently await your use of him.

RFK! RFK! RFK!Hints for upcoming updates (in no particular order; also size is simply due to the size of the photos I pulled off the internet):

View attachment 513741View attachment 513742View attachment 513743View attachment 513744View attachment 513745View attachment 513746View attachment 513747View attachment 513748View attachment 513749

Also check out that first photo.RFK! RFK! RFK!

The 1960s (part 2)

5 May 1969 – Abdeen Palace, Cairo, Egypt

“President Nasser, you may wanna see this.”

“What is it?”

“News from Ethiopia,” his secretary responded.

Nasser grumbled. No news from Ethiopia was good news.

“What’s going on?”

“Emperor Haile Selassie announced Ethiopia is going to try again to go forward with the dam.”

“What!? You’ve got to be kidding me! Let me see that report.”

He grabbed the piece of paper she was carrying. Sure enough, it was a transcript of a speech by the Ethiopian Emperor announcing the construction of a new dam on the Blue Nile.

“I’m sorry Malika, would you please step out of my office for a few seconds and close the door behind you?”

“Of course, Mr. President.”

She stepped out of the room and closed the door, standing right behind it. She could hear him shouting a few interesting choice words, followed by a shattering noise.

“Ok, you can come back in now.”

She re-entered the room. The shattered pieces of the ceramic pen-holding cup on his desk now covered the floor next to the wall by the door.

“Now, Malika, I would like for you to schedule a meeting for me to meet with my cabinet as soon as possible. There are very important matters at stake to be discussed.”

“Of course, Mr. President.”

“On second thought, perhaps I will brief them after the fact. Instead, I have a phone call to make.”

“Yes sir,” she said leaving the room.

Nasser picked up the phone on his desk and dialed in the number. He placed the phone by his ear and listened to the tone until the phone was picked up a few seconds later on the other end.

“It’s Nasser. Tell Mengistu it’s time. If Selassie refuses to back down on this dam, we will support him. The time has come for Operation Sphinx.”

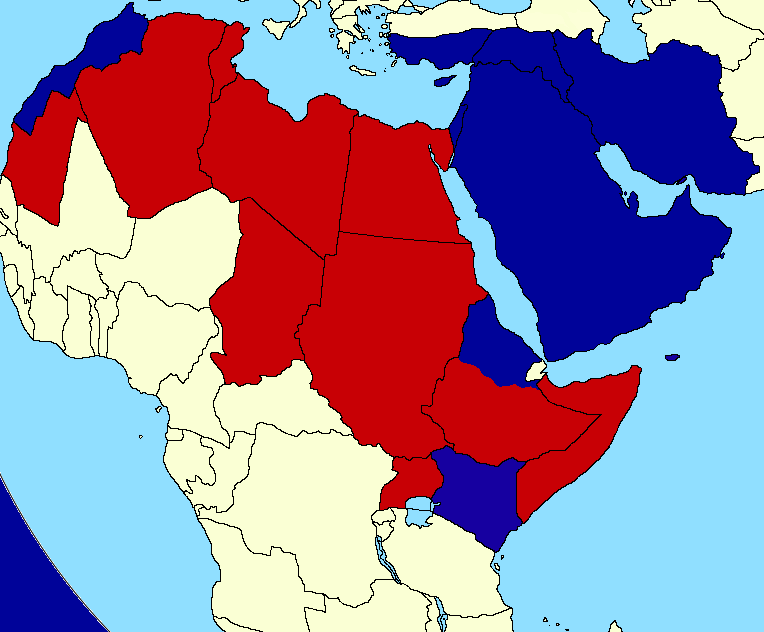

The 1960s was a decade that was full of both prosperity and with escalating tensions, tensions that would eventually lead to conflict on a massive scale. However, for now, the concerns were more immediate. Following Nasser’s announcement on 7 April 1964 of Egypt’s nuclear weapons, Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir announced that Israel and her allies would continue to fight the NAL and counter them at every term, declaring that the Naarist threat would spread no further, and was quickly joined by Iranian Prime Minister Asadollah Alam, Arabian Prime Minister Mohammad Najib ar-Ruba’i, and Kurdish President Ibrahim Ahmad.

However, spread further it did. On 29 September 1964, demonstrations in N’Djamena against Tombalbaye’s rule over Cameroon resulted in the national army opening fire onto the crowd in an event known as the N’Djamena Massacre. The massacre fueled a new wave of uprisings across Chad, much of which came to be associated with the Naarist movement. However, Chadian Naarism came to take a different form from that in the rest of the continent. Rather than being purely associated strictly with an Arab identity, it came to be more associated with revolution and national unity in a more vague sense, much of which was tied to the Arabic language and to its neighbors to the north and east, which were seen as allies to its liberation movement. On November 1, a coalition of Sudanese, Libyan, and Egyptian troops crossed the northern and eastern borders into Chad, aiding the already revolting Naarist forces. The following day, Cameroonian President Ahmadou Ahidjo sent Cameroonian forces into Chad from the southwest, defending the incumbent regime with which it had formed ties with the help of the AADP. The nations of the AADP began immediately sending forces to Cameroon with the intention of aiding the already present Cameroonian force. However, the moving of troops across the African continent proved to be quite slow and inefficient. On 13 December 1965, the Naarist force stormed the capital, causing the government in N’Djamena to flee across the border to take refuge in Cameroon. The new Chadian government, led by Naarist revolutionary Moussa Hisséne, would immediately request membership into the NAL and would immediately be accepted, with Nasser stating “it is an honor to see a nation newly liberated from the clutches of tyranny join our peaceful brotherhood”. Strategically, the AADP was not too concerned by this loss. The relationship with Tombalbaye’s regime was not a stable one, and offered little strategic gain rather than to maintain a foothold of the AADP’s influence in the center of the continent close to the NAL. However, the fall of Chad did make shockwaves throughout the media and to the public, indicating the rise of Egypt and the NAL as more of a powerful force to be reckoned with.

That same time also saw turmoil in Ethiopia. For the past decade and a half, the Ethiopian government had begun building settlements in the Ogaden region to move Ethiopians into the historically Somali land. On 9 December 1964, an Ethiopian military truck collided with a civilian car, killing 4 Somalis. This would incite a series of protests and unrests, and by the new year, it had scaled into an all-out violent uprising, seeing native Somalis carrying out terror attacks against Ethiopians whether they be military or civilian. This event was known as the Naxdin, or “The Tremor”. The violence lasted throughout the year into 1966, around which time the violence had begun to die down as Ethiopia improved the fortification of the settlements.

On the morning of 1 January 1966, the world was shocked to find that Sultan Faisal I, founder and head-of-state of the United Arab Sultanate, had died in his sleep the previous night alongside his wife, Huzaima. An official funeral was held and the couple was buried in the Arabian National Cemetery in Damascus, with the ceremony being televised to the masses and attended by government officials from across the nation, as well as numerous officials from Israel, Iran, Kurdistan, and Ethiopia as well. Later that evening, his son, Ghazi, was coronated as the new Sultan at the palace in Damascus. Even Nasser declared “although I regard the man as an adversary, I cannot deny that he has been an honorable and worthy rival.”

Meanwhile, in other parts of Africa, more political turmoil ensued. In mid-1965, Christophe Gbenye had gathered the remnants of the defeated Simba rebels in eastern Zaire and had attempted another revolt, requesting aid from Uganda to get the revolt off its feet. Although Obote, like the rest of his country, was personally opposed to the Zairean regime, he recognized that there would be little benefit to supporting them, and it would break Uganda’s previous stance of neutrality. It would also be especially harmful due to Obote’s plans to build a relationship with other East African neighbors such as Kenya, a country that was part of the AADP and was therefore loosely aligned with Mobutu’s regime. For this, he was criticized by long-time political ally and military commander, Idi Amin, who saw benefit to Ugandan support of the rebels, viewing Obote’s foreign policy as a mistake. Obote attempted to have Amin fired, but realized that doing such would harm him in the long run due to Amin’s popularity.

These weren’t Uganda’s only political struggles. Within Obote’s UPC, Grace Ibingira formed his own faction in an attempt to oust Obote as the party leader, and attempted to due so by gaining the support of the influential Buganda sub-kingdom. However, Buganda’s power would be shaken in 1964 by referendum’s in the county of Buyaga and Bugangaiza, which had earlier at the turn of the century been annexed by the Kingdom of Buganda from the Kingdom of Bunyoro. Following a referendum on 4 November 1964, voters chose to return to Bunyoro, diminishing the influence of Buganda.

This all would lead to a breakdown in the previous UPC-Buganda alliance in Uganda’s Parliament. On 24 February 1966, Obote announced the suspension of King Mutesa from his duties as President, while Mutesa protested and attempted to appeal to the UN to no avail. This led to the battle of Mengo Hill in Kampala, in which Mutesa and his supporters were defeated, and Mutesa escaped in a cab to the DRC, from where he would find asylum in the UK until his mysterious death in 1969. Following this crisis, Obote would suspend the constitution under the state of emergency and declare himself President that March, giving himself unlimited power until a new constitution could be drafted. To Obote’s credit, he did begin work on a new constitution within the next few months, although the design of said constitution did protect his power. Nonetheless, much of the populace slowly started to turn against him as he became increasingly authoritarian and as foreign investment and other international ties began to break down, harming the economy.

This provided an opening for Obote’s enemies. Despite ties from overseas powers breaking down, Obote still maintained some relationship with the other nations of the African Great Lakes region, such as Kenya and Tanzania. While he was in Dar Es Salaam meeting with Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere that July, Commander of the Army Idi Amin, with Egyptian support (due to Egyptian fears of Obote’s regime growing closer with Kenya), overthrew Obote’s government. Upon hearing the news, Obote took up refuge in Tanzania. Amin was largely supported by the masses due to his generally positive reputation as a heroic commander, although his cruelty would garner him heavy criticism from around the world, such as from Israeli author and human rights activist (later politician) Anat Frank-Peled. Amin’s first action was to strip all Asians and Europeans of their citizenship, blaming them for Uganda’s hardships and calling for their mass deportation or execution. Afterwards, he threatened Uganda’s Kenyan community with violence. He also declared that Uganda’s small population of those practicing traditional religions and Jews had to mark themselves and were forbidden from any sort of government position or wielding economic power and from marrying anyone outside of their own group. Immediately, the AADP condemned the coup, and Kenya threatened to invade unless the coup was reversed. In response, the much surprise, Egypt invited Uganda to the NAL. This surprised much of the world, considering how the NAL had primarily been an alliance between Naarist countries, with the exception being Somalia, which was at least historically connected with the Arab world. This new member of the alliance represented Egypt’s ambitions as a serious power beyond simply Northern Africa and the Arab World as well as its desire to combat the influence of the AADP. Frank-Peled also called for the Israeli government to allow the Abayudaya, the Jewish people of Uganda, to make Aliyah, although since they were not considered Halakhically Jewish by the Rabbinate, they were not considered valid, and the Israeli government would not take action to bring them to the country.

Meanwhile, in Nigeria, Civil War broke out on 6 July 1967 as the oil-rich Biafra seceded. In this conflict, both the AADP and NAL supported Nigeria against the rebels. However, as more information leaked on the humanitarian crisis on the ground as a result of the war, more individuals grow sympathetic to the Biafran cause. Leaked documents showed that the Israeli government considered switching sides, but it was found that pressure from other AADP nations convinced them not to out of a desire to not alienate the Nigerian government, pushing them to align with the NAL. Still, various NGOs, including the Israeli Humanitarian Aid Outreach Network (IHAON) founded by the 38-year-old Anat Frank-Peled, offered aid to the civilians of Biafra as well as civilians living on the Nigerian side. Due to large military support to Nigeria and pressure on Biafra to cease their uprising, Biafra announced their surrender on 9 April 1969.

3 July 1967 represented the ten-year anniversary of Algerian independence. This one day led to demonstrations in two countries. The first was in Algeria, where Berber minorities, particularly the Tuaregs in the south, demonstrated demanding equality under Algerian law, which at the time largely favored citizens who were Arab or who assimilated as such (including most of the Berber population. Algeria, at the time, would send in the military to crack down on the protesters, but would later agree to minor reforms, such as declaring Tamazight a minority language while still cracking down on the Tuareg in particular. The other set of demonstrations would take place in Morocco, particularly in the capital of Rabat, where Naarist demonstrators, sympathetic to Algeria and other nations with Naarist regimes, protested King Hasan II and his authoritarian dictatorial rule over Morocco, leading to mass arrests and incarcerations of protestors. Hasan’s increasing paranoia and authoritarianism would ultimately continue to breed more dissent. The demonstrations and arrests in Morocco would also inspire the Sahwri people of the Western Sahara territory to rise up in protest against Moroccan rule, which would soon escalate into violence. Mauritania, which had its own eyes on the territory offered to support the rebels against Morocco, although the rebels were quickly defeated. Seeing Mauritania as a valuable ally against Morocco, Algeria convinced the other nations of the NAL to offer Mauritania membership into the alliance, which it accepted.

Meanwhile, in Somalia, after 20 years of Presidency, Aden Abdulle Osman Daar stepped down from running again in 1968 (in part recognizing his failure to assist the Somali rebels in the Naxdin, allowing Siad Barre to win the election. Compared to Daar, Barre was much more of a stern authoritarian socialist. Whereas Daar adopted the marxist ideological convictions through a still democratic framework as part of his formation of a relationship with Egypt and the Soviets, Barre was deeply influenced by his own Islamic socialist ideals. “Islamic Socialism” would become the new term used to describe Barre’s mix of traditional Islamic faith with modern marxist ideals.

However, African nations were not the only ones facing large internal changes. In eastern Arabia, the Gulf Region, known as the Oil Belt, had been undergoing a large economic boom as a result of high demand for oil from the west. Coastal cities such as Kuwait, Jubayl, Dammam, Doha, Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Ras Al Khaimah, Fujairah, and Muscat all became wealthy off of the oil trade, with the city of Manama in the Emirate of Bahrain becoming the effective finance capital of the region, specializing in Islamic banking. While not the largest of these cities, Manama would lead the way on investment into the city’s modernization with the creation of larger banks, malls, boardwalks, as well as tourist attractions such as major hotels, features also seen in many of the other new cities of the Oil Belt. Many cities would take architectural influence from all over the world, with perhaps the largest influence on general architecture in the city being the Bauhaus architecture so common in Israeli Gush Dan cities such as Tel Aviv. The city as well as the rest of the island would undergo land-reclamation projects to increase its population. The city also grew to encompass nearby suburbs. It would also see the formation of the East Arabian Trade Center (EATC), a major new financial district built along the coast. The new EATC would begin construction in the late 1960s, with much of the construction being spearheaded by the Sultanate Binladen Group founded by Jeddah multi-millionaire Mohammad bin Awad bin Laden, including the massive EATC Twin Towers. The twin towers, originally dreamt of by Bin Laden himself, were set to be complete in 1970 and were designed to be the tallest skyscrapers in the world by the time of their completion.

With change, however, comes strife. The new economic miracle required new labor. Initially, workers started moving from the cramped old cities of sandy beige in the rest of the nation to the up-and-coming Gulf Coast in the early 1960s. This immediately create tensions between locals and migrants from other parts of the country. Peninsulars had historically been more conservative than those up north in the Fertile Crescent, and so individuals with large cultural and religious differences seemed to pose a threat to their way of life, one that was already changing under the new developments. In cities like Manama, Dammam, and Jubayl, the large influx of Sunni migrants brought them into conflict with the Shia locals, with the reverse happening in the Sunni cities further south with Shia migrants. The worse was in the coastal cities of the heavily Ibadi Oman, an autonomous minor Sultanate within the UAS with its historically unique identity, where both Sunni and Shia migrants appeared to be a threat to their way of life. However, the tension between locals and intranational migrants would soon be replaced by a more serious conflict. Starting in 1965, many of the local emirs, with permission from the national government, began inviting foreign migrants, particularly from South and Southeast Asia, to work in the cities as cheap labor, with the largest number of migrants coming from Indonesia, India, Pakistan, and Malaysia. There were also smaller numbers of migrants coming from nations in Africa, such as Kenya, Tanzania, Ethiopia, Portuguese Mozambique, and even as far as Nigeria. Almost immediately, as the supply of cheap labor increased, wages began to fall for the large portion of the already present workers who had not already climbed the economic hierarchy. At the infamous Anti-Displacement March in Abu Dhabi on 11 March 1968, hundreds of rioters took to the streets, many with torches, chanting “ln yuhiluu mahalna” (“They will not replace us”), attacking migrant laborers. The riot infamously included the highjacking of a car that was used to run into Indian migrant worker Sanjeev Rao, who left behind a wife and two daughters near Bangalore. Many onlookers were appalled by the open hostility and aggression towards migrants, and it caused many individuals throughout the country to also consider the poor treatment of migrant workers in the Oil Belt.

However, despite all the struggles, there was also a sort of romanticization of the Gulf Coast, with its beautiful modern buildings and beaches being seen as a contrast from the sprawling beige landscape of older cities in the rest of the country. As a result, in addition to migrant workers, many younger individuals moved to the city looking for opportunities in business, arts, and other sectors in the emerging cities. In this regard, the bustling growth combined with a vibrant youth culture, largely focused around life on the beaches. Khalij (Gulf) Music quickly became a popular new genre, with Fawz al-Khalij (Gulf Beat) becoming one of the most popular new boybands bands in Arabia.

However, by far the most popular new boyband in the Middle East was Rovikan (Foxes). Rovikan was a Kurdish boyband formed in early 1964 in Dortyol by a group of friends originally from Erbil. Continuing and evolving on the pop-Ruroq tradition of the previous decade, albeit with a softer tone, Rovikan sold out stadiums across Western Asia, performing in Kurdish as well as Farsi and Arabic, and sold more albums than any other artist in the Middle East. Rovikan was one of the first non-Turkish bands to perform in South Turkey in the capital of Adana on 28 August 1967, performing numerous songs in Turkish. Turkey had been undergoing a crisis of guilt, as the new generation came to wake up to the atrocities of the generations before them. First South Turkish President Celal Bayar had signed into law a bill pushed by the Allies requiring that education about World War II and the German and Turkish Holocausts be taught as a mandatory part of the curriculum, but with many still sympathetic to the old regime, it was not always well enforced until that point. Now, there was a large awakening in Turkish culture as the youth desired to learn more truth about their past and move onward into the future.

Iran also began to invest more in its oil sector. Similar to the investment going on across the gulf, Iran began to use oil money to build up its own coastal cities, with the largest being Bushehr, the new capital of Iran’s oil industry. In addition to export, Iran also invested large amounts of its resources on manufacturing, with Iran acting as the manufacturing giant of the Middle East, allowing its already large cities such as Tehran, Mashhad, Isfahan, Karaj, and Shiraz to vastly expand into sprawling manufacturing hubs. On 15 December 1965, Iranian Prime Minister Asadollah Alam convinced the Iranian Parliament to pass the Share Our Oil Act, creating a Sovereign Wealth Fund to manage Iran’s oil wealth, and using the money to establish basic services such as increased welfare benefits, universal healthcare, heavily subsidized public university tuitions (with medical training being free in order to increase the supply of doctors to uphold the universal healthcare system), as well as a monthly oil dividend given to all citizens, further increasing the standard of living in the nation. The UAS would soon follow suit with their own Share Our Oil Act in 1967. Other oil-rich nations, such as Libya, would adopt a similar system.

However, economics were not the only factor spreading the AADP’s influence overseas. The 1968 Election in the United States was an election between Republican Richard Nixon (VP Spiro Agnew), Democrat Robert Kennedy (VP Al Gore Sr.), and Independent segregationist George Wallace (VP Curtis LeMay). Initially, Nixon was in the lead, with Wallace snatching up the votes of segregationist Democrats, harming Robert Kennedy, who was known for his strong stances in favor of Civil Rights, opposition to the Vietnam War, and closer relations with the nations of the AADP, primarily emphasizing a relationship with Israel due to the popularity of the stance with Jews and liberals and conservative Evangelical Christians alike. The young 24-year-old Sirhan Sirhan, an Israeli-American of Palestinian* Christian background, proved himself to be a strong force in rallying support for Kennedy’s election among the youth. Kennedy would also receive the endorsement of Civil Rights leader Martin Luther King Jr (who also strongly supported Israel, due to his sympathy towards the Jewish people in addition to his viewing Israel as a positive example for an ethnically diverse yet relatively harmonious nation that the US should take after). This would all result in Kennedy receiving more and more of the former Liberal Republican vote. Additionally, the Wallace campaign would crash, leading to increases in support for both Kennedy and Nixon. Additionally, Nixon would be mocked for how he lost to Kennedy’s older brother, with jokes being made about how the same thing was destined to happen again eight years later, and while Kennedy condemned the jabs, it was enough to shake confidence in the Nixon campaign. In the end, Kennedy would win the election, marking the first time in American history that the brother of another President would occupy the Presidency, ironically beating the same opposing candidate to do so. In response to Kennedy’s election, Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev would reaffirm his commitment to support the North African League.

Within the Middle East and North Africa, more cultural changes were taking place. In Egypt and other North African nations, the old revolutionary fervor was beginning to die out. To the youth, the Naarists were less a new revolutionary force and more seen as the authoritative status quo. It was not uncommon for individuals to violate typical norms by listening to music from the AADP countries, with bands like Rovikan and Fawz al-Khalij being played at parties all over the country. The new generation was more liberal, exploring other ideologies and largely desiring more free speech and questioning the authoritarian of the one-party and even dictatorial regimes. These trends of liberalism also affected the nations of Western Asia as well. The youth in Western Asian countries became increasingly interested in the rise in Somali Rock, which tended to combine elements of Ruroq, Soul, and traditional Somali styles. Much of the youth, particularly in Iran, Saudi Arabia, and also in the African nation of Ethiopia began to question the legitimacy of the monarchies that had such power and prestige in their nations. The youth was largely disillusioned by the Cold War and the brutality of many of the leaders propped up by these alliances, such as Hassan II, Mobutu, and Idi Amin were seen as symbols of the horrors committed by their own governments. Drug use, especially psychedelics, became increasingly common across both sides. Heroin grown in Afghanistan began to make its way into Iran, from which it also spread to the rest of the region. Young Iranians in particular felt like their nation’s political struggle had nothing to do with the country itself, with the politics of the Sultanate against the Naarists having nothing to do with them. Film began to reflect this uncertainty and disillusionment in Western Asia. Looking for Arabia (1968) was a major example of an escapist film, telling the story of two men on a road trip across the UAS who, over the course of their journey, see poverty and other negative aspects of their society and have their innocence broken, turning to drugs. Conservative critics called for the film to be censored, and certain more conservative parts of the country, such as the Hejaz and Nejd would agree to censor the film. The Iranian film March to War (1967) told the story of two soldiers in Xerxes’ Army marching to Greece during the Persian War, battling at Thermopylae, and seeing the hardships of war first hand. In North Africa, where film had to be approved by the government, film largely had a patriotic message, designed to re-instill the revolutionary spirit in the youths, including the largely patriotic Egyptian film The Flame of Cairo (1968) told the story of the Naarist Revolutionaries fighting to free Cairo from the Turks during World War II. Omar Sharif was cast to play the Young Nasser, meant in part to redeem him as an actor after the controversy of him having previously played a character in the British film Lawrence of Arabia (1962).

Part of the increasing disillusionment also had to do with issues of Civil Rights. The issues of racial/religious justice as seen with the tensions between different geographic and religious groups as well as towards migrants in the Oil Belt were one such case. Very often, the emirate governments allowed migrant workers to face horrible conditions and did little to support them, with the national government not stepping in so that the issue may be left to the emirates. This injustice was often pointed to by the Naarist governments as prime examples of the superiority of the equal Naarist system (ironically ignoring the suppression of non-Arab identities in their own countries). Influenced by the Civil Rights movement in the US, a few thousand protesters decided to march down the streets of Damascus demanding the national government take action. Even Israel also had some religious tensions of their own. The Orthodox Rabbinate, set up as a compromise between the secular Zionists and the more religious Jews, controlled the religious lives of Jews, invalidating any Jewish marriages not performed by Orthodox Rabbis, and it was also the Rabbinate that decided who was considered a valid Jew to make Aliyah, as seen with the issue of the Abayudaya, as well as for many Ethiopian Jews who wanted to immigrate. These tensions were not the only issues. It wasn’t uncommon for Israelis and Arabians to visit each other’s countries, Israelis often traveling to find themselves after completing military service and Arabians traveling to see the holy city of Jerusalem. One thing that was apparent to people living in both countries was that there was far greater gender equality in Israel (a country that was even ruled by a female Prime Minister) than there was in the UAS. Even the Kurds and the Iranians also seemed to be ahead of much of the Sultanate in that regard. Although the Islamic Reformation movement following the end of WWII improved gender equality, there was still some ways to go, and so a new wave of feminism arose, advocating greater gender equality and included greater sexual liberation. Women increasingly felt comfortable wearing shorter clothes, using birth control (which was still illegal in many parts of the UAS), and living independently of men. The third issue, which impacted practically all countries in Western Asia, were LGBT rights. In pretty much every country in either the NAL or AADP, homosexuality was considered illegal. Despite this, the homosexual community existed in the underground, particularly in the cities of Tel Aviv, Beirut, and to a lesser extent Dortyol, which all had sizable Bohemian communities. On 15 April 1969, police attempted a raid on multiple gay clubs in Florentin, the Bohemian district of Tel Aviv. As a result, the gay community, led largely by drag queens, fought back against the police in the famous Florentin riots. The following day, once news reached Beirut, a similar demonstration took place there, with another smaller demonstration taking place in Dortyol. Although the riots were shut down, their legacy would live on as important for bringing LGBT rights to the forefront in the Middle East.

This would all culminate with Eilataba. Eilataba was a music festival that lasted from 18 May 1969 to 21 May 1969. The festival was held along Egypt-Israel border between the Israeli city of Eilat and the Egyptian town of Taba by the northern tip of the Gulf of Aqaba. The desert festival involved various performances taking place on stages on both sides of the border by artists from all over the Middle East and North Africa. The festival was known for its heavy drug use, particularly with regards to the use of cannabis (colloquially referred to as “Maryam”) as well as a variety of psychedelics. Young men and women from all over Egypt, Israel, and Arabia gathered in what would be remembered as a sort of drug- and sex-filled last stand before they would all be drafted and sent off to war, with the festival ending as soldiers from both sides moved to occupy the border. Soon, men who had been partying together would end up being forced to kill each other.

On 5 May 1969, one announcement would change everything. On that day, Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie stood before his people and declared his renewed intention of a dam on the Blue Nile. This immediately outraged Egyptian President Nasser and Sudanese President Ismail al-Azhari. On May 6, they issued an ultimatum to the Emperor– back down or face conflict. Not wanting to be told what to do and assuming that his allies would come to his aid should such conflict arise, he refused. Two weeks after the refusal, on 20 May 1969, the Communist Derg militia, led by Mengistu Haile Mariam, shocked the world by overthrowing the seemingly stable AADP-backed Ethiopian government, with Haile Selassie and his family and supporters in the government managing to successfully flee the capital to Mekele in the north. Immediately, the USSR, Egypt, and the other nations of the Warsaw Pact and the NAL recognized the new Ethiopian government. Of course, at the time the coup happened, there was not enough information to definitively confirm Egyptian involvement in the coup. Israeli PM Golda Meir and Arabian PM Bahjat Talhouni were the first to demand that the Egyptians withdraw their recognition of the new government, which Egypt refused. AADP forces quickly began landing on the Eritrean coast, sending forces to support the Emperor in the northern portion of the country. Seeing an opportunity, the local Somalis in the Ogaden rose up against remnants of the Ethiopian military loyal to the emperor in the region, causing Somalia to swiftly invade the region on their behalf on June 5. On 6 June 1969, Ethiopian Emperor Haile Selassie declared war on Somalia, sparking the start of the Second Ogaden War. Immediately, Egypt, Sudan, and Somalia declared war on the old Ethiopian government, calling the AADP on their bluff to support the Emperor and doing so under the pretense of ensuring mutual defense, and were quickly joined by the rest of the NAL. In response, Israel and the UAS declared war on the nations of the NAL under the same pretense, warning against nuclear force, stating that the use of any nuclear weapons on AADP soil would be met in kind, and the rest of the AADP would follow suit. The Great African War had begun. The world could only watch holding its breath. This was the start of the largest war since World War II, and it would be the first time in history that two nuclear powers would go to war.

9 June 1969 – Cairo, Egypt

“Yasser,” he said. “You are safe with me.”

Abdel Rahman Arafat knew the importance of having a good father because he didn’t. His childhood was full of abuse and suffering. Now, he had a fresh start. This baby he held in his arms was his fresh start.

Yasser. He always liked that name. He wished he could give himself that name. It was a perfect name for a perfect son.

For years, Arafat had no freedom. He had risen through the ranks. He had commanded men. But at the end of the day, no matter who was under him, he was trapped there. He was pressured to stay in the military. He was good at it, but it was beneath him. It wasn’t what he wanted to do. He wanted to be peaceful. He wanted to be a lawyer and good and just leader. But now, being done with the military, being home, never having to look back, and sitting on the couch with his son sleeping in his arms was all that he needed. Now he was free.

And then he heard the knock. The knock at the door that would change his life. Or rather, the knock that would bring back his past tenfold. He knew exactly what it was. Anyone who had followed the news of the past month would know what it was. He carried his son into the other room, lowering him gently into the crib. He then went back to open the door.

“General Arafat,” said the man in uniform at the door. “We need you immediately. Nasser demands it.”

“For what?” he asked as if he did not already know.

“The war, sir,” he said. “We are at war. We need all of our best officers and Nasser says you’re the best.”

“I finished a month ago. I am not looking back.”

“General Arafat, your country needs you. Egypt needs you. Your people need you.”

His people needed him.

He turned back to look at the crib in the other room. He thought about the future of the country he wanted to raise the child in. He looked back at man right outside his door.

“For my son,” he said. “For my son.”

And he followed the man out the door without saying goodbye.

*The term "Palestinian" in this TL doesn't necessarily refer to a distinct national identity, but is rather used as a term of ethnic identification referring to the population of Arabs within Israel who are Levantine, as opposed to the Bedouin Arabs of the south.

“President Nasser, you may wanna see this.”

“What is it?”

“News from Ethiopia,” his secretary responded.

Nasser grumbled. No news from Ethiopia was good news.

“What’s going on?”

“Emperor Haile Selassie announced Ethiopia is going to try again to go forward with the dam.”

“What!? You’ve got to be kidding me! Let me see that report.”

He grabbed the piece of paper she was carrying. Sure enough, it was a transcript of a speech by the Ethiopian Emperor announcing the construction of a new dam on the Blue Nile.

“I’m sorry Malika, would you please step out of my office for a few seconds and close the door behind you?”

“Of course, Mr. President.”

She stepped out of the room and closed the door, standing right behind it. She could hear him shouting a few interesting choice words, followed by a shattering noise.

“Ok, you can come back in now.”

She re-entered the room. The shattered pieces of the ceramic pen-holding cup on his desk now covered the floor next to the wall by the door.

“Now, Malika, I would like for you to schedule a meeting for me to meet with my cabinet as soon as possible. There are very important matters at stake to be discussed.”

“Of course, Mr. President.”

“On second thought, perhaps I will brief them after the fact. Instead, I have a phone call to make.”

“Yes sir,” she said leaving the room.

Nasser picked up the phone on his desk and dialed in the number. He placed the phone by his ear and listened to the tone until the phone was picked up a few seconds later on the other end.

“It’s Nasser. Tell Mengistu it’s time. If Selassie refuses to back down on this dam, we will support him. The time has come for Operation Sphinx.”

The 1960s (part 2)

The 1960s was a decade that was full of both prosperity and with escalating tensions, tensions that would eventually lead to conflict on a massive scale. However, for now, the concerns were more immediate. Following Nasser’s announcement on 7 April 1964 of Egypt’s nuclear weapons, Israeli Prime Minister Golda Meir announced that Israel and her allies would continue to fight the NAL and counter them at every term, declaring that the Naarist threat would spread no further, and was quickly joined by Iranian Prime Minister Asadollah Alam, Arabian Prime Minister Mohammad Najib ar-Ruba’i, and Kurdish President Ibrahim Ahmad.

However, spread further it did. On 29 September 1964, demonstrations in N’Djamena against Tombalbaye’s rule over Cameroon resulted in the national army opening fire onto the crowd in an event known as the N’Djamena Massacre. The massacre fueled a new wave of uprisings across Chad, much of which came to be associated with the Naarist movement. However, Chadian Naarism came to take a different form from that in the rest of the continent. Rather than being purely associated strictly with an Arab identity, it came to be more associated with revolution and national unity in a more vague sense, much of which was tied to the Arabic language and to its neighbors to the north and east, which were seen as allies to its liberation movement. On November 1, a coalition of Sudanese, Libyan, and Egyptian troops crossed the northern and eastern borders into Chad, aiding the already revolting Naarist forces. The following day, Cameroonian President Ahmadou Ahidjo sent Cameroonian forces into Chad from the southwest, defending the incumbent regime with which it had formed ties with the help of the AADP. The nations of the AADP began immediately sending forces to Cameroon with the intention of aiding the already present Cameroonian force. However, the moving of troops across the African continent proved to be quite slow and inefficient. On 13 December 1965, the Naarist force stormed the capital, causing the government in N’Djamena to flee across the border to take refuge in Cameroon. The new Chadian government, led by Naarist revolutionary Moussa Hisséne, would immediately request membership into the NAL and would immediately be accepted, with Nasser stating “it is an honor to see a nation newly liberated from the clutches of tyranny join our peaceful brotherhood”. Strategically, the AADP was not too concerned by this loss. The relationship with Tombalbaye’s regime was not a stable one, and offered little strategic gain rather than to maintain a foothold of the AADP’s influence in the center of the continent close to the NAL. However, the fall of Chad did make shockwaves throughout the media and to the public, indicating the rise of Egypt and the NAL as more of a powerful force to be reckoned with.

That same time also saw turmoil in Ethiopia. For the past decade and a half, the Ethiopian government had begun building settlements in the Ogaden region to move Ethiopians into the historically Somali land. On 9 December 1964, an Ethiopian military truck collided with a civilian car, killing 4 Somalis. This would incite a series of protests and unrests, and by the new year, it had scaled into an all-out violent uprising, seeing native Somalis carrying out terror attacks against Ethiopians whether they be military or civilian. This event was known as the Naxdin, or “The Tremor”. The violence lasted throughout the year into 1966, around which time the violence had begun to die down as Ethiopia improved the fortification of the settlements.

On the morning of 1 January 1966, the world was shocked to find that Sultan Faisal I, founder and head-of-state of the United Arab Sultanate, had died in his sleep the previous night alongside his wife, Huzaima. An official funeral was held and the couple was buried in the Arabian National Cemetery in Damascus, with the ceremony being televised to the masses and attended by government officials from across the nation, as well as numerous officials from Israel, Iran, Kurdistan, and Ethiopia as well. Later that evening, his son, Ghazi, was coronated as the new Sultan at the palace in Damascus. Even Nasser declared “although I regard the man as an adversary, I cannot deny that he has been an honorable and worthy rival.”

Meanwhile, in other parts of Africa, more political turmoil ensued. In mid-1965, Christophe Gbenye had gathered the remnants of the defeated Simba rebels in eastern Zaire and had attempted another revolt, requesting aid from Uganda to get the revolt off its feet. Although Obote, like the rest of his country, was personally opposed to the Zairean regime, he recognized that there would be little benefit to supporting them, and it would break Uganda’s previous stance of neutrality. It would also be especially harmful due to Obote’s plans to build a relationship with other East African neighbors such as Kenya, a country that was part of the AADP and was therefore loosely aligned with Mobutu’s regime. For this, he was criticized by long-time political ally and military commander, Idi Amin, who saw benefit to Ugandan support of the rebels, viewing Obote’s foreign policy as a mistake. Obote attempted to have Amin fired, but realized that doing such would harm him in the long run due to Amin’s popularity.

These weren’t Uganda’s only political struggles. Within Obote’s UPC, Grace Ibingira formed his own faction in an attempt to oust Obote as the party leader, and attempted to due so by gaining the support of the influential Buganda sub-kingdom. However, Buganda’s power would be shaken in 1964 by referendum’s in the county of Buyaga and Bugangaiza, which had earlier at the turn of the century been annexed by the Kingdom of Buganda from the Kingdom of Bunyoro. Following a referendum on 4 November 1964, voters chose to return to Bunyoro, diminishing the influence of Buganda.

This all would lead to a breakdown in the previous UPC-Buganda alliance in Uganda’s Parliament. On 24 February 1966, Obote announced the suspension of King Mutesa from his duties as President, while Mutesa protested and attempted to appeal to the UN to no avail. This led to the battle of Mengo Hill in Kampala, in which Mutesa and his supporters were defeated, and Mutesa escaped in a cab to the DRC, from where he would find asylum in the UK until his mysterious death in 1969. Following this crisis, Obote would suspend the constitution under the state of emergency and declare himself President that March, giving himself unlimited power until a new constitution could be drafted. To Obote’s credit, he did begin work on a new constitution within the next few months, although the design of said constitution did protect his power. Nonetheless, much of the populace slowly started to turn against him as he became increasingly authoritarian and as foreign investment and other international ties began to break down, harming the economy.

This provided an opening for Obote’s enemies. Despite ties from overseas powers breaking down, Obote still maintained some relationship with the other nations of the African Great Lakes region, such as Kenya and Tanzania. While he was in Dar Es Salaam meeting with Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere that July, Commander of the Army Idi Amin, with Egyptian support (due to Egyptian fears of Obote’s regime growing closer with Kenya), overthrew Obote’s government. Upon hearing the news, Obote took up refuge in Tanzania. Amin was largely supported by the masses due to his generally positive reputation as a heroic commander, although his cruelty would garner him heavy criticism from around the world, such as from Israeli author and human rights activist (later politician) Anat Frank-Peled. Amin’s first action was to strip all Asians and Europeans of their citizenship, blaming them for Uganda’s hardships and calling for their mass deportation or execution. Afterwards, he threatened Uganda’s Kenyan community with violence. He also declared that Uganda’s small population of those practicing traditional religions and Jews had to mark themselves and were forbidden from any sort of government position or wielding economic power and from marrying anyone outside of their own group. Immediately, the AADP condemned the coup, and Kenya threatened to invade unless the coup was reversed. In response, the much surprise, Egypt invited Uganda to the NAL. This surprised much of the world, considering how the NAL had primarily been an alliance between Naarist countries, with the exception being Somalia, which was at least historically connected with the Arab world. This new member of the alliance represented Egypt’s ambitions as a serious power beyond simply Northern Africa and the Arab World as well as its desire to combat the influence of the AADP. Frank-Peled also called for the Israeli government to allow the Abayudaya, the Jewish people of Uganda, to make Aliyah, although since they were not considered Halakhically Jewish by the Rabbinate, they were not considered valid, and the Israeli government would not take action to bring them to the country.

Meanwhile, in Nigeria, Civil War broke out on 6 July 1967 as the oil-rich Biafra seceded. In this conflict, both the AADP and NAL supported Nigeria against the rebels. However, as more information leaked on the humanitarian crisis on the ground as a result of the war, more individuals grow sympathetic to the Biafran cause. Leaked documents showed that the Israeli government considered switching sides, but it was found that pressure from other AADP nations convinced them not to out of a desire to not alienate the Nigerian government, pushing them to align with the NAL. Still, various NGOs, including the Israeli Humanitarian Aid Outreach Network (IHAON) founded by the 38-year-old Anat Frank-Peled, offered aid to the civilians of Biafra as well as civilians living on the Nigerian side. Due to large military support to Nigeria and pressure on Biafra to cease their uprising, Biafra announced their surrender on 9 April 1969.

3 July 1967 represented the ten-year anniversary of Algerian independence. This one day led to demonstrations in two countries. The first was in Algeria, where Berber minorities, particularly the Tuaregs in the south, demonstrated demanding equality under Algerian law, which at the time largely favored citizens who were Arab or who assimilated as such (including most of the Berber population. Algeria, at the time, would send in the military to crack down on the protesters, but would later agree to minor reforms, such as declaring Tamazight a minority language while still cracking down on the Tuareg in particular. The other set of demonstrations would take place in Morocco, particularly in the capital of Rabat, where Naarist demonstrators, sympathetic to Algeria and other nations with Naarist regimes, protested King Hasan II and his authoritarian dictatorial rule over Morocco, leading to mass arrests and incarcerations of protestors. Hasan’s increasing paranoia and authoritarianism would ultimately continue to breed more dissent. The demonstrations and arrests in Morocco would also inspire the Sahwri people of the Western Sahara territory to rise up in protest against Moroccan rule, which would soon escalate into violence. Mauritania, which had its own eyes on the territory offered to support the rebels against Morocco, although the rebels were quickly defeated. Seeing Mauritania as a valuable ally against Morocco, Algeria convinced the other nations of the NAL to offer Mauritania membership into the alliance, which it accepted.

Meanwhile, in Somalia, after 20 years of Presidency, Aden Abdulle Osman Daar stepped down from running again in 1968 (in part recognizing his failure to assist the Somali rebels in the Naxdin, allowing Siad Barre to win the election. Compared to Daar, Barre was much more of a stern authoritarian socialist. Whereas Daar adopted the marxist ideological convictions through a still democratic framework as part of his formation of a relationship with Egypt and the Soviets, Barre was deeply influenced by his own Islamic socialist ideals. “Islamic Socialism” would become the new term used to describe Barre’s mix of traditional Islamic faith with modern marxist ideals.

However, African nations were not the only ones facing large internal changes. In eastern Arabia, the Gulf Region, known as the Oil Belt, had been undergoing a large economic boom as a result of high demand for oil from the west. Coastal cities such as Kuwait, Jubayl, Dammam, Doha, Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Ras Al Khaimah, Fujairah, and Muscat all became wealthy off of the oil trade, with the city of Manama in the Emirate of Bahrain becoming the effective finance capital of the region, specializing in Islamic banking. While not the largest of these cities, Manama would lead the way on investment into the city’s modernization with the creation of larger banks, malls, boardwalks, as well as tourist attractions such as major hotels, features also seen in many of the other new cities of the Oil Belt. Many cities would take architectural influence from all over the world, with perhaps the largest influence on general architecture in the city being the Bauhaus architecture so common in Israeli Gush Dan cities such as Tel Aviv. The city as well as the rest of the island would undergo land-reclamation projects to increase its population. The city also grew to encompass nearby suburbs. It would also see the formation of the East Arabian Trade Center (EATC), a major new financial district built along the coast. The new EATC would begin construction in the late 1960s, with much of the construction being spearheaded by the Sultanate Binladen Group founded by Jeddah multi-millionaire Mohammad bin Awad bin Laden, including the massive EATC Twin Towers. The twin towers, originally dreamt of by Bin Laden himself, were set to be complete in 1970 and were designed to be the tallest skyscrapers in the world by the time of their completion.

With change, however, comes strife. The new economic miracle required new labor. Initially, workers started moving from the cramped old cities of sandy beige in the rest of the nation to the up-and-coming Gulf Coast in the early 1960s. This immediately create tensions between locals and migrants from other parts of the country. Peninsulars had historically been more conservative than those up north in the Fertile Crescent, and so individuals with large cultural and religious differences seemed to pose a threat to their way of life, one that was already changing under the new developments. In cities like Manama, Dammam, and Jubayl, the large influx of Sunni migrants brought them into conflict with the Shia locals, with the reverse happening in the Sunni cities further south with Shia migrants. The worse was in the coastal cities of the heavily Ibadi Oman, an autonomous minor Sultanate within the UAS with its historically unique identity, where both Sunni and Shia migrants appeared to be a threat to their way of life. However, the tension between locals and intranational migrants would soon be replaced by a more serious conflict. Starting in 1965, many of the local emirs, with permission from the national government, began inviting foreign migrants, particularly from South and Southeast Asia, to work in the cities as cheap labor, with the largest number of migrants coming from Indonesia, India, Pakistan, and Malaysia. There were also smaller numbers of migrants coming from nations in Africa, such as Kenya, Tanzania, Ethiopia, Portuguese Mozambique, and even as far as Nigeria. Almost immediately, as the supply of cheap labor increased, wages began to fall for the large portion of the already present workers who had not already climbed the economic hierarchy. At the infamous Anti-Displacement March in Abu Dhabi on 11 March 1968, hundreds of rioters took to the streets, many with torches, chanting “ln yuhiluu mahalna” (“They will not replace us”), attacking migrant laborers. The riot infamously included the highjacking of a car that was used to run into Indian migrant worker Sanjeev Rao, who left behind a wife and two daughters near Bangalore. Many onlookers were appalled by the open hostility and aggression towards migrants, and it caused many individuals throughout the country to also consider the poor treatment of migrant workers in the Oil Belt.

However, despite all the struggles, there was also a sort of romanticization of the Gulf Coast, with its beautiful modern buildings and beaches being seen as a contrast from the sprawling beige landscape of older cities in the rest of the country. As a result, in addition to migrant workers, many younger individuals moved to the city looking for opportunities in business, arts, and other sectors in the emerging cities. In this regard, the bustling growth combined with a vibrant youth culture, largely focused around life on the beaches. Khalij (Gulf) Music quickly became a popular new genre, with Fawz al-Khalij (Gulf Beat) becoming one of the most popular new boybands bands in Arabia.

However, by far the most popular new boyband in the Middle East was Rovikan (Foxes). Rovikan was a Kurdish boyband formed in early 1964 in Dortyol by a group of friends originally from Erbil. Continuing and evolving on the pop-Ruroq tradition of the previous decade, albeit with a softer tone, Rovikan sold out stadiums across Western Asia, performing in Kurdish as well as Farsi and Arabic, and sold more albums than any other artist in the Middle East. Rovikan was one of the first non-Turkish bands to perform in South Turkey in the capital of Adana on 28 August 1967, performing numerous songs in Turkish. Turkey had been undergoing a crisis of guilt, as the new generation came to wake up to the atrocities of the generations before them. First South Turkish President Celal Bayar had signed into law a bill pushed by the Allies requiring that education about World War II and the German and Turkish Holocausts be taught as a mandatory part of the curriculum, but with many still sympathetic to the old regime, it was not always well enforced until that point. Now, there was a large awakening in Turkish culture as the youth desired to learn more truth about their past and move onward into the future.

Iran also began to invest more in its oil sector. Similar to the investment going on across the gulf, Iran began to use oil money to build up its own coastal cities, with the largest being Bushehr, the new capital of Iran’s oil industry. In addition to export, Iran also invested large amounts of its resources on manufacturing, with Iran acting as the manufacturing giant of the Middle East, allowing its already large cities such as Tehran, Mashhad, Isfahan, Karaj, and Shiraz to vastly expand into sprawling manufacturing hubs. On 15 December 1965, Iranian Prime Minister Asadollah Alam convinced the Iranian Parliament to pass the Share Our Oil Act, creating a Sovereign Wealth Fund to manage Iran’s oil wealth, and using the money to establish basic services such as increased welfare benefits, universal healthcare, heavily subsidized public university tuitions (with medical training being free in order to increase the supply of doctors to uphold the universal healthcare system), as well as a monthly oil dividend given to all citizens, further increasing the standard of living in the nation. The UAS would soon follow suit with their own Share Our Oil Act in 1967. Other oil-rich nations, such as Libya, would adopt a similar system.

However, economics were not the only factor spreading the AADP’s influence overseas. The 1968 Election in the United States was an election between Republican Richard Nixon (VP Spiro Agnew), Democrat Robert Kennedy (VP Al Gore Sr.), and Independent segregationist George Wallace (VP Curtis LeMay). Initially, Nixon was in the lead, with Wallace snatching up the votes of segregationist Democrats, harming Robert Kennedy, who was known for his strong stances in favor of Civil Rights, opposition to the Vietnam War, and closer relations with the nations of the AADP, primarily emphasizing a relationship with Israel due to the popularity of the stance with Jews and liberals and conservative Evangelical Christians alike. The young 24-year-old Sirhan Sirhan, an Israeli-American of Palestinian* Christian background, proved himself to be a strong force in rallying support for Kennedy’s election among the youth. Kennedy would also receive the endorsement of Civil Rights leader Martin Luther King Jr (who also strongly supported Israel, due to his sympathy towards the Jewish people in addition to his viewing Israel as a positive example for an ethnically diverse yet relatively harmonious nation that the US should take after). This would all result in Kennedy receiving more and more of the former Liberal Republican vote. Additionally, the Wallace campaign would crash, leading to increases in support for both Kennedy and Nixon. Additionally, Nixon would be mocked for how he lost to Kennedy’s older brother, with jokes being made about how the same thing was destined to happen again eight years later, and while Kennedy condemned the jabs, it was enough to shake confidence in the Nixon campaign. In the end, Kennedy would win the election, marking the first time in American history that the brother of another President would occupy the Presidency, ironically beating the same opposing candidate to do so. In response to Kennedy’s election, Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev would reaffirm his commitment to support the North African League.

Within the Middle East and North Africa, more cultural changes were taking place. In Egypt and other North African nations, the old revolutionary fervor was beginning to die out. To the youth, the Naarists were less a new revolutionary force and more seen as the authoritative status quo. It was not uncommon for individuals to violate typical norms by listening to music from the AADP countries, with bands like Rovikan and Fawz al-Khalij being played at parties all over the country. The new generation was more liberal, exploring other ideologies and largely desiring more free speech and questioning the authoritarian of the one-party and even dictatorial regimes. These trends of liberalism also affected the nations of Western Asia as well. The youth in Western Asian countries became increasingly interested in the rise in Somali Rock, which tended to combine elements of Ruroq, Soul, and traditional Somali styles. Much of the youth, particularly in Iran, Saudi Arabia, and also in the African nation of Ethiopia began to question the legitimacy of the monarchies that had such power and prestige in their nations. The youth was largely disillusioned by the Cold War and the brutality of many of the leaders propped up by these alliances, such as Hassan II, Mobutu, and Idi Amin were seen as symbols of the horrors committed by their own governments. Drug use, especially psychedelics, became increasingly common across both sides. Heroin grown in Afghanistan began to make its way into Iran, from which it also spread to the rest of the region. Young Iranians in particular felt like their nation’s political struggle had nothing to do with the country itself, with the politics of the Sultanate against the Naarists having nothing to do with them. Film began to reflect this uncertainty and disillusionment in Western Asia. Looking for Arabia (1968) was a major example of an escapist film, telling the story of two men on a road trip across the UAS who, over the course of their journey, see poverty and other negative aspects of their society and have their innocence broken, turning to drugs. Conservative critics called for the film to be censored, and certain more conservative parts of the country, such as the Hejaz and Nejd would agree to censor the film. The Iranian film March to War (1967) told the story of two soldiers in Xerxes’ Army marching to Greece during the Persian War, battling at Thermopylae, and seeing the hardships of war first hand. In North Africa, where film had to be approved by the government, film largely had a patriotic message, designed to re-instill the revolutionary spirit in the youths, including the largely patriotic Egyptian film The Flame of Cairo (1968) told the story of the Naarist Revolutionaries fighting to free Cairo from the Turks during World War II. Omar Sharif was cast to play the Young Nasser, meant in part to redeem him as an actor after the controversy of him having previously played a character in the British film Lawrence of Arabia (1962).

Part of the increasing disillusionment also had to do with issues of Civil Rights. The issues of racial/religious justice as seen with the tensions between different geographic and religious groups as well as towards migrants in the Oil Belt were one such case. Very often, the emirate governments allowed migrant workers to face horrible conditions and did little to support them, with the national government not stepping in so that the issue may be left to the emirates. This injustice was often pointed to by the Naarist governments as prime examples of the superiority of the equal Naarist system (ironically ignoring the suppression of non-Arab identities in their own countries). Influenced by the Civil Rights movement in the US, a few thousand protesters decided to march down the streets of Damascus demanding the national government take action. Even Israel also had some religious tensions of their own. The Orthodox Rabbinate, set up as a compromise between the secular Zionists and the more religious Jews, controlled the religious lives of Jews, invalidating any Jewish marriages not performed by Orthodox Rabbis, and it was also the Rabbinate that decided who was considered a valid Jew to make Aliyah, as seen with the issue of the Abayudaya, as well as for many Ethiopian Jews who wanted to immigrate. These tensions were not the only issues. It wasn’t uncommon for Israelis and Arabians to visit each other’s countries, Israelis often traveling to find themselves after completing military service and Arabians traveling to see the holy city of Jerusalem. One thing that was apparent to people living in both countries was that there was far greater gender equality in Israel (a country that was even ruled by a female Prime Minister) than there was in the UAS. Even the Kurds and the Iranians also seemed to be ahead of much of the Sultanate in that regard. Although the Islamic Reformation movement following the end of WWII improved gender equality, there was still some ways to go, and so a new wave of feminism arose, advocating greater gender equality and included greater sexual liberation. Women increasingly felt comfortable wearing shorter clothes, using birth control (which was still illegal in many parts of the UAS), and living independently of men. The third issue, which impacted practically all countries in Western Asia, were LGBT rights. In pretty much every country in either the NAL or AADP, homosexuality was considered illegal. Despite this, the homosexual community existed in the underground, particularly in the cities of Tel Aviv, Beirut, and to a lesser extent Dortyol, which all had sizable Bohemian communities. On 15 April 1969, police attempted a raid on multiple gay clubs in Florentin, the Bohemian district of Tel Aviv. As a result, the gay community, led largely by drag queens, fought back against the police in the famous Florentin riots. The following day, once news reached Beirut, a similar demonstration took place there, with another smaller demonstration taking place in Dortyol. Although the riots were shut down, their legacy would live on as important for bringing LGBT rights to the forefront in the Middle East.

This would all culminate with Eilataba. Eilataba was a music festival that lasted from 18 May 1969 to 21 May 1969. The festival was held along Egypt-Israel border between the Israeli city of Eilat and the Egyptian town of Taba by the northern tip of the Gulf of Aqaba. The desert festival involved various performances taking place on stages on both sides of the border by artists from all over the Middle East and North Africa. The festival was known for its heavy drug use, particularly with regards to the use of cannabis (colloquially referred to as “Maryam”) as well as a variety of psychedelics. Young men and women from all over Egypt, Israel, and Arabia gathered in what would be remembered as a sort of drug- and sex-filled last stand before they would all be drafted and sent off to war, with the festival ending as soldiers from both sides moved to occupy the border. Soon, men who had been partying together would end up being forced to kill each other.