Ah China is truly blessed in this timeline by having Big Di energy...Thank you! Sometimes I kinda figure I should pull a van Gulik and just keep writing about our Magistrate Di -- but alas, we need to get back to the rest of China eventually. Even so, I have a feeling we'll see a little more of Magistrate Di in the future...

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Restoration of the Great Ming: A Tianqi Timeline

- Thread starter RexSueciae

- Start date

He'll be back!A funny thing to do is to forget about Di entirely and then have him pop up later in the historical chronicles like a long-lost friend

Incidentally, in the book The Years of Rice and Salt (premise being that the Black Death is normal-ish in the rest of the world but absolutely wipes out Europe, leading to all sorts of changes), since it's set over the very long term, one of the running themes of the book is how some characters who appear in different chapters (from different time periods) are very clearly reincarnations of each other -- you'll see people with similar names showing up in the future, not lineal descendants but people with similar personality traits and so forth -- anyways. I'd have to keep this timeline running for a very very long time in order to do something like that, but the thought has occurred to me. As a plot device, if nothing else.

...Ah China is truly blessed in this timeline by having Big Di energy...

[headdesk]

The Curious Adventures of Judge Dee [Chapter Eight]

Luoyang Market Square, Dongshan

The Admiral was going to be absent. He’d taken another expedition along the east coast. Best of luck to him; it was something more in line with his skills. Which meant that Magistrate Di was in charge of organizing the execution.

He was pretty sure he’d be doing this sort of thing anyways, under normal circumstances. The Admiral was already known to the people. It was now his job to show his face, make himself known, and, when necessary, dispense justice as the emperor’s representative.

The approval from Beijing had arrived uneventfully. The murderer was to die.

Gao and Yang led forth the condemned man, bound him to a post. He went without protesting, clearly half-dazed. That might have been a small mercy. Magistrate Di had found another helper from the populace to serve as official executioner. The man waited patiently as the prisoner was secured, then stepped forward with a rope.

It took a surprisingly long time. Magistrate Di steadfastly refused to look away until it was done.

The crowd murmured a bit when the dead man finally stopped twitching. That was fine. Word had gotten around how this callow youth had committed murder out of a moment’s greed. (The Admiral was keeping the bit about gold very hush-hush for now. Still, everyone figured the merchant had been carrying something valuable. There were all sorts of rumors.)

They approved. Or, at the least, they didn’t disapprove. He hoped he’d made a good first impression.

Magistrate Di shook his head. Of course he had. He’d already gotten two additional petitions from the residents of Luoyang. One had to do with the theft of a substantial quantity of fabric, which was something he’d have to investigate. The other was a bit of incredibly stupid intra-family drama, and the magistrate had shouted them out of the yamen for wasting his time.[1]

“Well,” Mr. Lu said after it was all over, “your first case, and it all went well. I hope every case should be like that.”

“I’d prefer if we didn’t have any more murders, Mr. Lu.”

“Er-”

“I know, that wasn’t what you meant.” Magistrate Di sighed. “And this isn’t even the beginning of all the work we’ve got to do.”

“Ah?”

“So many things on my agenda. There’s the new school I want to set up,” Magistrate Di ticked it off on his fingers. “Try to teach the Classics to some of the kids, and maybe in a few years we’ll have exam candidates from Dongshan. Get the yamen building spruced up. Try to regularize business in the taxation department, and you know that’ll be very important if the Admiral finds what he’s looking for in the east. And then there’s still the necessity of leaving enough time to receive petitions from the common folk.” He sighed again. “At least Beijing will be sending more people to help out. Eventually.”

“Maybe when they do, you’ll get a promotion,” Mr. Lu offered hopefully.

“Wouldn’t mind that.” Magistrate Di made an indifferent gesture. “No use to think about it now. C’mon, let’s go find that fisherman who said he had information on the missing cloth. I have a feeling this witness will be less important than advertised, but you never know...”

End of excerpt

We return to our normally scheduled program

Magistrate Di Yimin will return

Footnote

[1] This was especially pronounced during the late Qing IOTL, when the court system was strained to the brink, but imperial Chinese magistrates were not very happy when family disputes escalated into lawsuits. A vast number of surviving records have the magistrate telling everyone off for dragging the court into a private affair.

The Admiral was going to be absent. He’d taken another expedition along the east coast. Best of luck to him; it was something more in line with his skills. Which meant that Magistrate Di was in charge of organizing the execution.

He was pretty sure he’d be doing this sort of thing anyways, under normal circumstances. The Admiral was already known to the people. It was now his job to show his face, make himself known, and, when necessary, dispense justice as the emperor’s representative.

The approval from Beijing had arrived uneventfully. The murderer was to die.

Gao and Yang led forth the condemned man, bound him to a post. He went without protesting, clearly half-dazed. That might have been a small mercy. Magistrate Di had found another helper from the populace to serve as official executioner. The man waited patiently as the prisoner was secured, then stepped forward with a rope.

It took a surprisingly long time. Magistrate Di steadfastly refused to look away until it was done.

The crowd murmured a bit when the dead man finally stopped twitching. That was fine. Word had gotten around how this callow youth had committed murder out of a moment’s greed. (The Admiral was keeping the bit about gold very hush-hush for now. Still, everyone figured the merchant had been carrying something valuable. There were all sorts of rumors.)

They approved. Or, at the least, they didn’t disapprove. He hoped he’d made a good first impression.

Magistrate Di shook his head. Of course he had. He’d already gotten two additional petitions from the residents of Luoyang. One had to do with the theft of a substantial quantity of fabric, which was something he’d have to investigate. The other was a bit of incredibly stupid intra-family drama, and the magistrate had shouted them out of the yamen for wasting his time.[1]

“Well,” Mr. Lu said after it was all over, “your first case, and it all went well. I hope every case should be like that.”

“I’d prefer if we didn’t have any more murders, Mr. Lu.”

“Er-”

“I know, that wasn’t what you meant.” Magistrate Di sighed. “And this isn’t even the beginning of all the work we’ve got to do.”

“Ah?”

“So many things on my agenda. There’s the new school I want to set up,” Magistrate Di ticked it off on his fingers. “Try to teach the Classics to some of the kids, and maybe in a few years we’ll have exam candidates from Dongshan. Get the yamen building spruced up. Try to regularize business in the taxation department, and you know that’ll be very important if the Admiral finds what he’s looking for in the east. And then there’s still the necessity of leaving enough time to receive petitions from the common folk.” He sighed again. “At least Beijing will be sending more people to help out. Eventually.”

“Maybe when they do, you’ll get a promotion,” Mr. Lu offered hopefully.

“Wouldn’t mind that.” Magistrate Di made an indifferent gesture. “No use to think about it now. C’mon, let’s go find that fisherman who said he had information on the missing cloth. I have a feeling this witness will be less important than advertised, but you never know...”

End of excerpt

We return to our normally scheduled program

Magistrate Di Yimin will return

Footnote

[1] This was especially pronounced during the late Qing IOTL, when the court system was strained to the brink, but imperial Chinese magistrates were not very happy when family disputes escalated into lawsuits. A vast number of surviving records have the magistrate telling everyone off for dragging the court into a private affair.

Last edited:

1635

Talisman to ward off plague, excerpted from literature of Gao Lian (reprinted circa 1635)

Two major events took place in 1635 that still didn’t manage to be the single most dramatic moment of the year. (From the perspective of the court in Beijing, of course. Plenty of dramatic events are happening elsewhere -- a hurricane wrecked some of England's New World colonies, and Shah Jahan down in India has unveiled a truly remarkable throne, following which he ordered the demolition of the Jesuits' headquarters -- but that's another story.)

In central China, Hong Chengchou and Daišan finally move against the Yellow Tiger. They had been sweeping through the countryside putting out fires, but now, at last, they are able to face China’s most notorious bandit leader.

The outlaw army is not caught unawares, seeing as a large Ming force is unlikely to be particularly sneaky. Of course, neither are they; the two armies are doing a very good job of demonstrating how warfare is only really practical in areas with sufficient food supplies. The two armies are also doing a good job of demonstrating how large bodies of men will rapidly deplete even the most fertile farmlands of surplus food.

Hong Chengchou makes at least some attempt to pay for anything that his soldiers “forage,” although undoubtedly this was little more than a token effort. It is entirely possible that later chronicles played up his actions in order to make him look better. Realistically, there is no way that he would have been able to adequately recompense everyone. Still, it’s acknowledged that he tried his best. The fact is that while the Yellow Tiger has made a policy of recruiting disaffected peasants to join his cause (just like every other upjumped warlord), the truth remains that hungry peasants tend to get angry at whomever is currently stealing their food. All armies need food, and the Yellow Tiger’s army is no exception.

This is probably why battle commences early in the year. While the skirmish is usually known as the Battle of Mianshan, it actually occurred a fair distance from the sacred mountain, to the point where some modern historians think that the mountain itself was barely visible (if at all) to the combatants. The results are mostly inconclusive. Hong Chengchou and Daišan jointly claim victory, but the Yellow Tiger slips away in the aftermath. The Yellow Tiger’s supporters claim victory, but they have to abandon the region. Never again will the Yellow Tiger range so far north.

Incidentally, Hong Chengchou and Daišan are getting along just fine. Hong Chengchou is well aware that Ming armies, typically lacking in cavalry, have long recruited from northern steppe peoples, and sees this as an unexceptional continuation of that trend. The fact that Daišan and the Plain Red Banner came to reinforce him just in time is also a good thing. Daišan, for his part, appreciates that Hong Chengchou isn’t a complete dickhead. There will be glory for the victories they will win together, he thinks to himself.

(Those who have read “The Yellow Tiger’s Fury” or viewed any of its modern dramatic adaptations may suspect a deeper relationship between the two. Historians are greatly divided on the subject.)

Up north, Yuan Chonghuan leads a substantial field army against Ligdan Khan (or possibly Ejei Khan, his son; sources aren’t exactly clear on which one was in de facto control at this point, although Ligdan Khan did fall ill several times before his eventual confirmed death in the next year). This battle, again, is inconclusive. The Chakhar mostly fall back in the face of Ming advances and the Ming are not able to pursue them with sufficient speed. Yuan Chonghuan does reassert Ming sovereignty over the contested areas, routing the small units of (usually junior) horsemen who had miscalculated their retreat.

Ajige of the Jurchens does not respond, being very busy fighting off yet another coup attempt. Besides, he had no real sentiment for Ligdan Khan. So Yuan Chonghuan’s expedition is mostly unopposed, and is counted as a success in Beijing for its show of force.

Yuan Chonghuan himself argues for another expedition the following year. He believes that, though the Mongols have been cowed, they need to be well and truly smashed, remembering his great victories against the Jurchens years earlier. Also, so long as everyone gets back in time for the harvest, it might actually be a good idea to take a bunch of peasant levies out where they can’t cause trouble. Win-win.

Knowing the general’s stature, most people at court nod approvingly at the suggestion.

In any other year, the twin victories (or close enough) against the Yellow Tiger and Ligdan Khan would’ve been the most important events in the chronicles. In most worlds, they undoubtedly would have been, for 1635 was by most counts an uneventful year -- for a while.

Later in the year, the emperor’s uncle Zhu Changxun, Prince of Fu (favorite son of the Tianqi Emperor’s grandfather, who would have been heir to the imperial throne if it were not for the rigid traditions of the court) falls ill. He had recently traveled to a part of China where tremendous numbers of peasants had grown sick and died, on business or for some unknown purpose. What is known is that the Prince of Fu was very sick, his body covered with bloody pustules and, reportedly, blood visible in his vomit. He lingers for five days before dying.[1]

It is the first time that this generation of Ming nobility has to grapple with the fact that the plague has arrived. Of course, the plague itself has not yet spread to Beijing; the Prince of Fu, from his estate in rural Henan province, was simply unfortunate enough to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. His death alarmed the court, focused minds on an issue that had until then been a distant thing, a problem for the peasantry.

The plague was one disease for which there was no sure remedy. The Prince of Fu had many decent physicians in attendance, who, we are told, tried many cures listed in the Bencao Gangmu to no avail. The best cure was prevention; failing that, luck.

Zhu Yousong, the Prince of Dechang, succeeds his father as Prince of Fu. The emperor’s cousin travels from Beijing back to the family estate to properly mourn his father. According to some accounts, he refuses to even enter the household for nearly a week, until the servants are able to convince him that the place has been thoroughly cleansed and that nobody else was infected.

The resulting delay to the funerary procedures was a trifle unfilial, and some in Beijing clucked their tongues at the prince’s actions. Nobody was so gauche as to actually laugh, but it was a silly little distraction from the ordinary day-to-day.

A pity that it could not have happened a year later.

Footnote

[1] As noted in the 1628 update, his death IOTL was not pleasant. That fate has been butterflied away and another one takes its place. Sorry, man.

Oof. Seems like the plague is inevitable now.[1] As noted in the 1628 update, his death IOTL was not pleasant. That fate has been butterflied away and another one takes its place. Sorry, man.

Yep. I can't butterfly away an event like that entirely -- especially considering all the armies tramping around the place where it apparently began. Good news is that IOTL it took a little while to actually make it to Beijing, so we've got a little bit of leeway for now.Oof. Seems like the plague is inevitable now.

Good question. Not sure if there'll be a lever to push on my end. We might see the Tianqi Emperor get a little bit miffed about how the Mughals are treating the Jesuits, since he's friends with some of 'em. Of course, even considering the fact that China at this time was what later writers might call a "great power" (keeping in mind that the idea of great powers is very much a product of a specific time, and it's not helpful to apply labels too far into the past for fear of misleading people), there might not they can do directly about it. They can be pissed off, though.Will dara take the throne rather than aurangzeb in this timeline?

I guess he could threat to open China's market to some of the Mughal's rivals if he really is pissed off, which would get his message across, but its very unlikely they would actually do thatGood question. Not sure if there'll be a lever to push on my end. We might see the Tianqi Emperor get a little bit miffed about how the Mughals are treating the Jesuits, since he's friends with some of 'em. Of course, even considering the fact that China at this time was what later writers might call a "great power" (keeping in mind that the idea of great powers is very much a product of a specific time, and it's not helpful to apply labels too far into the past for fear of misleading people), there might not they can do directly about it. They can be pissed off, though.

I don't really see any need for action against Mughals, while Emperor is friends with Jesuits one must ask himself are events in Mughal empire truly that important to Ming interests? At the cost of causing needless diplomatic spat with Mughals? Any wise burocract and advisor wouldn't say so. Plus keeping calm helps Jesuit position within Ming empire as well, they have some opposition at court that they managed to overcome via support from the Emperor and keeping their heads down, last thing they need is being in the spotlight like this.

It's far better to resolve this calmly, from my understanding Emperor isn't really Jesuit, or Christian and while he has friends among them in Ming empire he has no greater reason to act in their protection outside the empire.

It's far better to resolve this calmly, from my understanding Emperor isn't really Jesuit, or Christian and while he has friends among them in Ming empire he has no greater reason to act in their protection outside the empire.

1636, part 1

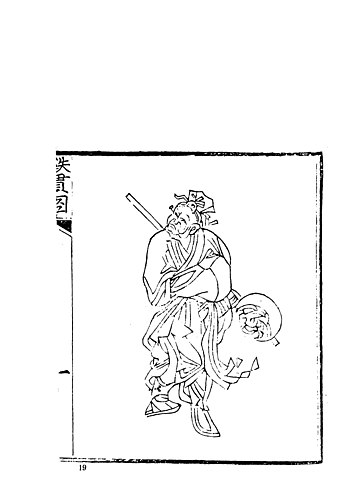

Probable depiction of Zhang Xianzhong, the "Yellow Tiger"

During the most troubled years of the Tianqi era, occasional peasant armies ravaged entire provinces -- or made very game attempts at doing so -- in search of food, or vengeance, or something else. The Army of the Yellow Tiger is perhaps the best-documented of the group, and tends to occupy an outsized place in both the scholarly literature and popular perception.

Starting around this time, the most influential sources dealing with the subject mostly draw from the writings of Wang Wei, the courtesan-turned-poet who appears to have settled down in the Sichuan area during this time -- which is to say, directly in the path of the rampaging rebels as they recoiled from the army led by Hong Chengchou and Daišan. Wang Wei, along with her husband Xu Yuqing, whom she’d married in 1624,[1] were guests of the noblewoman Qin Liangyu, and appear to have occupied positions of honor at her court.

(Students of history should be reminded that while speculation as to the relationship between Wang Wei, Xu Yuqing, and Qin Liangyu is a popular topic in the genre of historical fiction, much of the popularly accepted “common knowledge” about the trio can be ultimately traced to the Wanzhou Forgeries, a document cache of spurious provenance that was likely composed more than a century after its claimed date. That being said, rumors may have circulated contemporary to these events, especially when noting Wang Wei’s extremely laudatory treatment of Qin Liangyu in her poetry.)

According to Wang Wei, when the Yellow Tiger approached Sichuan, Qin Liangyu did what she was good at doing: she raised an army. Truthfully, she may have been more experienced than most in the Ming military bureaucracy. She’d led armies in Sichuan and Guizhou against rebels before. What was one more collection of rabble to her?

Thus, when the Army of the Yellow Tiger approached Sichuan, they found they were facing significantly stiffer resistance. True, they had never really gotten open cooperation from the locals -- as noted previously, many discontented and hungry peasants ended up attaching themselves to a bandit leader, but people who still had something to lose generally didn’t like the idea of losing it.

But the typical behavior of a peasant farmer facing an approaching army was to hide anything that could be valuable (food, usually, including the seed grain for the next planting season, although modern imagination tends to think of hard currency when they imagine “valuables”) and to melt into the forests. Better to not be there when the army comes.

This time, the bandits faced a hastily-levied army that actively sought to fight them. Despite Wang Wei’s breathless depiction of the events, the clashes that erupted between the two forces were really more brawls than anything else.

On the one hand, you had an irregularly armed, poorly-disciplined mob of peasants. On the other hand, you had...an irregularly armed, poorly-disciplined mob of peasants. Both were fighting, arguably, for survival; the difference was that one side was additionally fighting to protect their homes.

Even so, the Army of the Yellow Tiger might have eventually overwhelmed the locals by sheer force of numbers -- time had taken its toll, of course, but the army was still a threat -- if the relief army led by Hong Chengchou and Daišan had not slammed into their rear.

Wang Wei, in her literary works chronicling the campaign, seems to imply a concerted effort on the part of the various commanders in the region, brilliantly surrounding and decisively defeating a dangerous foe. Recent historical reassessments have tended to demonstrate that luck played a much greater role than previously thought. This is not to diminish the talent that Qin Liangyu displayed in holding together the local levies against their enemies, nor should it diminish the logistical skills of Hong Chengchou and Daišan. However, in an age when the fastest communications technology was “man-on-horse,” there was likely little to no communication between the two Ming forces. The Army of the Yellow Tiger fled from one of its opponents and crashed into another, finding itself broken like a chunk of pottery on a blacksmith’s anvil.

Of course, the victors of the great battle weren’t thinking much of the historiographical implications of recent events. After their victory, they were celebrating -- there was an impromptu festival held in the vicinity of Linshui -- although their soldiers, poking through the bodies of the dead, raised a somewhat disconcerting question.

Where was the Yellow Tiger?

His physical appearance is relatively well-attested in primary sources of the era. (Distinctive complexion, “tiger chin,” impressive stature, fierce demeanor.) And yet none of the corpses recovered from the battlefield seemed to match the description.

There are several plausible theories. The first is that Zhang Xianzhong, the original Yellow Tiger, had been killed in battle years ago and had been replaced by a figurehead or opportunist who made use of his name. The second is that the Yellow Tiger’s body had been overlooked or was disfigured to the point of being unrecognizable, thus escaping notice in the battle’s aftermath.

The third is that the Yellow Tiger, with some of his followers, escaped into the countryside, lying low somewhere (or ensuring silence via intimidation or murder) in order to fight again.

This last theory won immediate acceptance at the time and has, to the present day, majority support in the scholarly community. By some accounts, the Yellow Tiger was at large as late as the 1650s, doing various bandit-type things and causing trouble. But the “Yellow Tiger” who was active in the 1650s was probably a fake; historians have tentatively identified at least five “Tigers” (or False Tigers for the true pedant) in the historical record.

Some of these “Tigers” were easily distinguished because of their physical descriptions, which may have slightly varied from what is known of Zhang Xianzhong. At least one was easily distinguishable from the rest because he was apprehended by Ming forces in 1640 and summarily executed. As for the remainder, who can say? People change in appearance as they age. Maybe the Yellow Tiger -- the real one -- kept at it for years after the battle at Linshui. Maybe he walked away and found peace, somewhere far from the field of blood. Maybe he had been dead all along.

But the Ming armies had (at the cost of considerable bloodshed) restored a temporary order to the region. There would be further unrest, but not quite so existentially threatening. The local garrisons would remain on the lookout for further appearances of the Yellow Tiger (or his imposters). In fact, many members of the victorious armies were eventually resettled in the area, replacing lives lost from war or famine or plague. This is the reason why the dialects and languages of the Sichuan area bear a strong degree of mutual intelligibility with those of North China and, to a degree, with the speech of the Jurchens, owing to the veterans of the Plain Red Banner who had followed Daišan from the northern frontier.[2]

Dutifully, a report was composed for the imperial court, detailing the great victory and the likely mopping-up operations that would be conducted to ensure the Yellow Tiger was well and truly dead. Interestingly, this would be the second time in two years that this part of China would be overshadowed by events taking place elsewhere.

Footnotes

[1] This is OTL.

[2] IOTL, the Sichuanese language(s) received tremendous influence from other Chinese populations due to internal immigration following Yuan- and Ming-era depopulation. Zhang Xianzhong was blamed for a lot of the depopulation at the end of the Ming dynasty, although arguably he was a convenient scapegoat for the Qing to use for their propaganda. That being said, relatively impartial Jesuit witnesses agree that he was definitely capable of excessive violence. I should note that IOTL there is some dispute over how Zhang Xianzhong died but it is agreed that he died approximately when people say he did.

Y'know, I actually do have thoughts in that direction -- but that'll be someone else's topic to conquer!The Yellow Tiger as presented here is such a thrilling figure

Honestly I kinda lowkey wish there was some other chinese TL where he somehows claim the Mandate of Heaven, I mean...wouldnt be the first Emperor to have been a bandit~

Yes Im talking about you Liu Bang

ITTL we can expect a similar sort of vibe around Zhang Xianzhong, sort of like a darker Robin Hood. There's less explicit Qing propaganda ("look at this horrible guy we defeated, you're welcome China") but also maybe less romanticization ("he fought the Qing therefore he can't be all bad"). Still, historic figures tend to look better centuries down the line, and historical fiction has a way of making heroes out of less-than-heroic figures. You can bet that you'll have plenty of people cosplaying him ITTL (and since I've been making repeated references to "The Yellow Tiger's Fury" as a work of literature, probably there'll be all sorts of adaptations for film and TV or whatever the equivalent names for those inventions would be).

Can you provide Wang Wei’s name in Chinese? I have some trouble finding her name in English sources.Starting around this time, the most influential sources dealing with the subject mostly draw from the writings of Wang Wei, the courtesan-turned-poet who appears to have settled down in the Sichuan area during this time -- which is to say, directly in the path of the rampaging rebels as they recoiled from the army led by Hong Chengchou and Daišan. Wang Wei, along with her husband Xu Yuqing, whom she’d married in 1624,[1] were guests of the noblewoman Qin Liangyu, and appear to have occupied positions of honor at her court.

Oh dear, what now?Interestingly, this would be the second time in two years that this part of China would be overshadowed by events taking place elsewhere.

王微 (this one!)Can you provide Wang Wei’s name in Chinese? I have some trouble finding her name in English sources.

Oh dear, what now?

I'll try to get the next update out soon-ish (got family visiting plus work stuff going on, so things might be delayed) but I thought it might be worth noting that 1) according to alternatehistory.com, this timeline has already reached a length of 33.5k words, and 2) on the Google Doc where I keep my rough draft, the last update brought us to precisely 100 footnotes! (Google Docs doesn't let you restart footnote numbering.)

Maybe the real Yellow Tiger was the friends we made along the wayThere are several plausible theories. The first is that Zhang Xianzhong, the original Yellow Tiger, had been killed in battle years ago and had been replaced by a figurehead or opportunist who made use of his name. The second is that the Yellow Tiger’s body had been overlooked or was disfigured to the point of being unrecognizable, thus escaping notice in the battle’s aftermath.

The third is that the Yellow Tiger, with some of his followers, escaped into the countryside, lying low somewhere (or ensuring silence via intimidation or murder) in order to fight again.

1636, part 2

Mongol horse archer, from manuscript produced during Ming dynasty

History is rarely made in an instant.

To the popular mind, though, there will always remain a handful of decisive, shocking events upon which human civilization seems to turn. This is, of course, usually an illusion, a simplification which conceals events and trends of more distant origin.

Let’s back up a little.

In 1635, Yuan Chonghuan had led a Ming army against the Mongols and achieved unmistakable, though limited, success. His advocacy brought another Ming army together to do the same thing in 1636. The campaign would get lots of angry young men out of the way, keeping them from causing trouble, while also seeking to humble one of the dynasty’s ancient foes. (The Jurchens, still roiling with civil war, are more or less ignored, but it’s expected that such a show of force will intimidate them as well.)

Yuan Chonghuan and his army had given the Chakhar a tremendous shove, although they had not moved fast enough to completely destroy the Mongol armies. The army of 1636 was probably not going to be significantly faster, although its size (even larger than last year’s) was hopefully enough to contain and eventually destroy those who had raided Ming territory.

(Ming policy towards “northern barbarians” is a complicated subject. Sometimes, emperors attempted to placate raiders with trade goods. Other times, emperors ordered military action. The current leadership of the Ming bureaucracy is not in a negotiating mood.)

Modern historians sometimes debate Yuan Chonghuan’s motivations and ultimate goals for the 1636 campaign. While a final subjugation of the Northern Yuan was obviously in the cards, some evidence suggests that an even grander objective was intended, including (partially substantiated) boasts that the army would advance as far as the ruins of Karakorum.[1]

The Northern Yuan, at this point, were led by Ejei Khan, who is de jure as well as de facto ruler of his people. (His father, Ligdan Khan, has recently died, reportedly while comatose during his final illness.) He is younger, perhaps a little less experienced, but he is certainly his father’s son. He is not about to give up without a fight.

Still, his warriors fall back before the Ming armies just as they did the previous year. It takes all of his diplomatic skill to accomplish such a thing. It helps that the more querulous types had died the previous year fighting the Ming.

They fall back, and continue to fall back, in the face of the advance. For Yuan Chonghuan’s army is advancing at a relatively slow pace, even accounting for lessons learned the previous year. Moving men across the steppe is difficult, but they must keep up the pace or face even more severe logistical issues. Food must be transported, water must be found. And that’s not to mention the light cannon, smaller firearms, gunpowder, and shot.

If it is able to anchor itself to a secure position, the Ming army will be very difficult to face. A Mongol charge is a terrifying thing, horses thundering towards you, their riders firing off arrows the whole time before swinging around for one final shot: armies that break and run (or who advance in an ill-disciplined charge when they see the horsemen “retreating”) tend to get annihilated. But Yuan Chonghuan has been drilling his soldiers, and they’ve learnt that staying put and blasting away at the enemy is a great boon to morale.

Ejei Khan is reluctant to face the Ming head-on. Perhaps his father would have actively harassed them, forced them to keep alert during the day. But Ejei hesitates.

He does notice, though, that when the Ming army sets up camp for nightfall, there is, potentially, vulnerability. True, the army does its best to dig in, set up firing positions, the works. That’s not easy on the steppe. Wagons can be lined up to make impromptu firing positions, maybe. That’s about it, though. It’s not like there’s trees to be felled for shelter, and the army doesn’t carry digging tools to make earthworks.

An amateur might consider a night attack, when the Ming soldiers are at their most vulnerable, mostly asleep. Ejei considers and rejects this option. His horsemen need to be able to see in order to fight.

He attacks at dawn.

It’s in the grey light of the early morning that his army comes pouring across the steppe, smashing into the Ming. There had been sentries posted, but they mostly died where they stood. Those that got away provided maybe a few seconds of warning.

So the Mongols cut through the Ming lines and swarm into the Ming camp, shooting arrows at anything that moves. Here, their momentum breaks down a little as many riders pause to pillage the camp. (In fairness to them, far more disciplined armies throughout history have been tempted into doing the exact same thing.) This gives the Ming enough time to fall back to prepared positions. When the riders charge at the impromptu redoubt formed by wagons and crates piled into barricades, they are bloodily repulsed, the air thick with gunpowder smoke. The Mongols can keep riding around the place shooting arrows but horses lack the sheer punching power of armored vehicles (still hundreds of years away): there is no way a rider on a horse can smash through a wooden barricade without taking potentially life-threatening damage. (Also, horses like to throw riders who pull stunts like that.)

Ming chronicles assert that a counter-attack from the defenders finally drove the Mongol forces away from the Ming camp; primary sources from the Northern Yuan are a little thin on the ground, but appear to imply that the attackers withdrew of their own accord. The Ming acquit themselves well: their steppe nomad enemies can ill afford the terrible losses that they took this day.

However, that does not mean that the Ming army escaped unscathed. Of the vast host that sallied out from Beijing, approximately one-third is dead or missing. The army eventually returns home, badly mauled even in victory. And they bear with them the body of their commander, Yuan Chonghuan, Marquis of Ningyuan -- slain during the height of the battle, he passes from the mortal realm to the immortal pages of history.

Footnotes

[1] Although Karakorum was a major settlement and de facto capital city dating back to the reign of Ögedei, it was later eclipsed by other cities of the Yuan (including Khanbaliq, on the site of modern-day Beijing) and by the 1600s was probably a ghost town, its stones salvaged for the construction of Erdene Zuu Monastery. Occupying the ruins of Karakorum would be a signal that the Ming demand not just the submission of the Northern Yuan remnants, but of the Mongol people in general.

Last edited:

A Narrative Interlude [1636]

The Meridian Gate

As his servants helped him into his most formal robes, he wondered why he couldn’t feel a damned thing.

His wife, upon hearing of the Marquis of Ningyuan’s death, had burst into tears. The stalwart general had been a dear friend. To think that he was gone...

He promised to return. He promised us that.

And so the general had returned, but in a wooden box carried by his soldiers. All that was mortal of the man who had broken the Jin and who would have done the same to the old foes, the descendants of the Yuan.

Emperors don’t weep. But even if they were allowed, he didn’t think he’d be capable of it. He’d expected to feel sad. Bereft, even. Instead, there’s just a blankness, a void.

The servants looked a little frightened of him. Or maybe worried for him. He couldn’t tell. It didn’t matter.

“This way, your majesty,” someone murmured, and he stalked out of the room. He had duties.

The Meridian Gate was maybe his favorite part of the palace -- besides, of course, the room where he keeps all his woodworking equipment. Its balcony looks out over a great granite courtyard, high up above the bustle down below.

Today, the courtyard was not filled with ordinary passerby, court officials and workers and so forth. Instead, there were battalions of soldiers, clad in fine armor, and each man stood beside a prisoner. The prisoners wore red, as was tradition, and their arms were bound as they were made to kneel before the emperor.

This was an old ceremony, one that his grandfather had done and his father before him, probably all the way back to early times. Back before the Meridian Gate had been built and the capital was another city. It was not new to the emperor. He knew his role.

Zhou Qiyuan, his Minister of Justice, stoop-shouldered with age but still clear-voiced, unrolled a scroll. “August majesty,” he formally began, “these vile enemies of peace stand accused of the following offenses...”

The emperor let his mind wander. His most senior courtiers stood beside him, and many guards beside them. It wasn’t that impressive of a ceremony. None of the more important Mongols had been captured. That so-called Khan was still out there somewhere. Well, this would show him what it meant to pick a fight with the Great Ming.

Minister Zhou read quickly. “And therefore,” he concluded, “I petition that these men be taken to the execution ground without delay and put to death with the sword, for their varied and sundry crimes against all civilization!”

The crowd held its breath, waiting for his response.

And so the emperor said the words that were used in such occasions: “Take them there,” he said quietly. “Be it so ordered.”

“Be it so ordered!” The command was taken up by his courtiers, and then the guards, and soon nearly every Chinese voice was echoing the command. “BE IT SO ORDERED!”

The soldiers down in the square began hauling away their prisoners, heading straight for the execution ground. The crowd roared its approval.

Be it so ordered!

The emperor remained standing at the balcony until the last voice had died away, the last prisoner was gone. Then he turned and allowed his servants to help him away from public view.

He wondered why it was so cold this time of year.

Last edited:

Share: