Chapter 82: Mire of Misery

The campaigning season in 1855 would begin rather early as General Nikolay Muravyov departed from his winter quarters in late February, hoping to catch the Ottomans off guard. Advancing from their encampment outside Horasan with the 5th, 18th, and 21st Infantry Divisions, the Caucasian Grenadier Division, 2 regiments of cavalry (His Majesty’s Nizhny Novgorod Regiment of Dragoons and His Majesty’s Tver Regiment of Cuirassiers), 24 cannon batteries, and a contingent of Armenian and Georgian volunteers; his target would be the city of Erzurum which had narrowly eluded him only a few months prior. The trek westward would be incredibly difficult for the Russians as they battled both Kurdish partisans and Ottoman sentries, but their worst adversary would be the terrain, as the snow-covered trails and dirt paths of Eastern Anatolia were a mess of ice and mud making them a poor avenue for an army over 90,000 strong. Nevertheless, they continued in spite of it all, driven onward by the indominable will of General Muravyov.

His efforts would be for naught however, as Abdi Pasha would discover Muravyov’s lumbering advance well before the Russians reached Erzurum and began preparing for their arrival. Arraying his well-rested army before the walls of Erzurum, Abdi Pasha hoped to repeat the successful defense of the previous December, by making the Russians bleed themselves white against his stout fortifications. Muravyov would not disappoint, as he launched an immediate assault on the Ottoman fieldworks outside Erzurum in what was quickly becoming a trend for the aggressive Russian general. Waves of men charged towards the Ottoman lines with muskets raised and bayonets fixed. The Turks, numbering around 53,000 men were greatly outnumbered, but with their strong defensive works, they hoped to hold firm against the Russians for some time. Even still, the Turks were hard pressed all along the line in the face of such an overwhelming attack.

With his line becoming increasingly thin, Abdi Pasha elected to fall back to a secondary line of defenses nearer the city, but in the din of the battle, this information would not be properly relayed to all his troops. Seeing many of their compatriots leaving the battlefield, several Turkish irregulars presumed they had been abandoned and predictably panicked, choosing to flee rather than stand and fight. Naturally, this left a noticeable hole in the Ottoman line, a hole that Muravyov quickly found and broke through with relative ease. With that, the battle of Erzurum was well and truly lost for the Ottomans. That defeat very quickly became a disaster as the victorious Russians surged forward, capturing or killing nearly one third of the Ottoman Army including the unfortunate Abdi Pasha who died whilst attempting to rally his men.

Around a quarter of the Ottoman army would escape behind the walls of Erzurum where they would choose to make their stand. Most, however, would flee to the South under the direction of Abdülkerim Nadir Pasha where they would later rendezvous with Selim Pasha’s Army of 24,000. Together, Abdülkerim Pasha hoped that their united front could counter Muravyov’s host, trapping it between the walls of Erzurum and their army. For this plan to work, however, they would need to act fast, unite their forces, and attack the Russians before they took the city. To their credit, they would meet six days later near the ancient castle of Hasan Kale and began quickly marching their combined army to relieve Erzurum. However, to their dismay, Erzurum had fallen in less than ten days despite the valor of its defenders and the strength of their defenses as General Muravyov launched assault after assault on the city until it fell. Although a few hundred men remained holed up within the city’s citadel, the fall of Erzurum was now all but assured.

Worse still, Muravyov’s scouts would soon learn of the Ottoman army marching against them, prompting the Russian General to ready his army for battle, while he left behind a small screening force to continue besieging Erzurum’s citadel. Demoralized and exhausted after twelve days of hard marching, Abdülkerim Pasha’s and Selim Pasha’s army would be brushed aside with relative ease. But in a surprising moment of restraint and caution, Muravyov refrained from pursuing the defeated Turks, choosing instead to return to the siege of Erzurum’s citadel. With their only hope of salvation now dashed, the remaining Ottoman defenders within Erzurum’s keep finally surrendered to Muravyov’s men, opening the gateway to the Anatolian heartland.

Emboldened by his success, General Muravyov would opt to plunge deeper into the Ottoman countryside, after giving his men a day to rest and recuperate. Departing Erzurum on the 14th of March, Muravyov’s advance towards Erzincan would be made harder by the poor condition of the roads and growing opposition from the local Turkish and Kurdish partisans who resist him with increasing fanaticism. The weather also continued to turn against the Russians as much of the snow had now begun to melt, turning the dirt roads of Eastern Anatolia into bogs of mud, slowing Muravyov’s already glacial pace considerably. Worse still, many of Muravyov’s carriages and wagons became lodged in this muck, including most of his heavy artillery, forcing further delays. For a man who built his reputation on aggressive charges and forced marches, this snail’s pace was incredibly infuriating for the brash Russian commander.

After three days of limited progress - having only moved two and a half miles, the old General had had enough and simply pushed on ahead without his baggage and artillery trains, leaving several hundred irregulars behind to aid in their recovery, while he and the main contingent continued marching westward. With his wagons and carts now unhitched, Muravyov’s pace improved, as the Russians would reach the outskirts of Erzincan after another nine days of hard marching. Unlike Erzurum, however, the Ottomans defending the town, had elected not to face off against the Russians in a field battle. Instead, they would choose to remain holed up behind their walls.

Taking the initiative, General Muravyov ordered an assault on the town, but this time things were different as the Russian soldiers had been worn ragged by a month of forced marches and constant fighting across difficult terrain. Moreover, Erzincan’s defenders were in good spirits and in a strong position to repel the Russian attack, albeit at a considerable cost. Another attempt to storm Erzincan the following day would see some progress, but was ultimately driven back when the city’s garrison - aided by several hundred civilians - counterattacked in force. When he pressed his deputies to make another assault the following day, Muravyov’s subordinates threatened to mutiny. Faced with no other option, the old general rescinded his previous orders and began establishing proper siegeworks.[1] Complicating matters for Muravyov, however, was his lack of artillery, most of which was still stuck on the road between Erzincan and Erzurum. Unable to take the city by storm or bombard it into submission, Muravyov was forced to starve it into surrendering instead, a process that would take far longer than he ever expected.

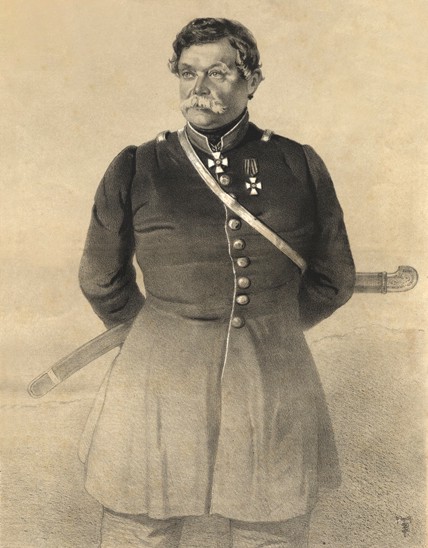

General Nikolay Muravyov, circa 1854

Contrasting greatly with General Muravyov’s aggressive campaigning in Eastern Anatolia, Count Paskevich would take a far more cautious approach in the Balkans having learned the hard way where reckless attacks and foolhardy valor led the previous year. In preparation for this year’s offensive, his newly vaunted “

Army of the Danube” had been significantly augmented over the Winter to well over 246,000 men, most of whom were divided between Prince Mikhail Dimitrievich Gorchakov’s

Army of Wallachia and Count Alexander von Lüders’

Army of Moldavia. Comprised of 12 Infantry Divisions (including 2 Grenadier Divisions), 4 Cavalry Divisions (three Light Cavalry and one Cuirassier Divisions), 4 Artillery Divisions (equipped with 56 artillery batteries), and an unspecified number of Wallachian, Moldavian and Bulgarian “volunteers”, properly supplying such a massive force was simply beyond Russia’s means, even during times of peace.

To minimize the material shortages and quality deficiencies of his troops, Count Paskevich would construct a series of supply depots over the Winter, and stocked them with as much powder, cannonballs, musket balls, food, and uniforms that he could find. He would also build a series of new roads from Bucharest and Iasi to the Danube, in an attempt to ease the movement of munitions and foodstuffs to the front. To protect these depots against British naval raids, the Namiestnik would erect a series of forts and outposts near the Black Sea’s coast and large portions of the Danube Delta to ward off British ships. It was far from a perfect solution as supply shortages would continue to plague the Russians for the remainder of the war, but Paskevich’s efforts would help minimize some of these issues to a degree.[2]

Paskevich’s efforts to improve his army’s logistic network would do little to address some of the more pressing problems of the Russian Army, namely the sordid camp life many of his soldiers endured, nor did he improve the medical treatment his troops received. Like most military encampments prior to the modern day, little attention was given to a camp’s cleanliness. Contamination of water supplies was a common issue for most pre-modern bivouacs due to poorly positioned privies upstream of the camps. Little concern was given to removing trash and human waste from the campgrounds, making them prime breeding grounds for disease carrying rodents and insects.

Added to this was the poor personal hygiene many soldiers of the day exhibited and the inadequate rations most received, all of which made them incredibly susceptible to ailments and illness. Cholera was particularly prevalent at Silistra, targeting Russian, Ottoman, and Briton alike without prejudice. The rather crude medical practices of the time which still relied heavily on bloodletting and pseudoscience rather than proven medicines or tested techniques would only make matters worse. Many sick and wounded would become invalidated or die after receiving this misguided “treatment”, when they could have recovered completely or survived with better medical care. Before the fighting in 1855 even began, the effective fighting strength of the Russian Army of the Danube had been sapped by nearly a quarter from an official total of 246,523 men to an actual strength around 184,000 soldiers for much of the campaigning season.[3]

The Russians at Silistra

The Russians at Silistra

Standing against Paskevich’s still considerable host was the Ottoman “

Army of Rumelia”, led by the old Serbian exile, Omar Pasha Latas. Like its Russian counterpart, the Ottoman Army had been reinforced from 97,000 soldiers in November 1854 to a little over 131,0000 by March 1855. However, unlike the Russians, these reinforcements represented the last veteran reservists available to the Porte who would now be forced to call upon fresh conscripts and irregulars for additional manpower. Moreover, many of these soldiers were forced to guard a large stretch of the Danube from Silistra to Turnu in order to fend off Russian crossings further upstream. Many were also stationed far from the front in Serbia, Thessaly, Epirus, and Macedonia keeping the peace in these rowdy provinces and contending with the multiple revolts which had erupted since the war began.

Fortunately for the Ottomans, they were supplemented by the British Army’s “

Balkan Expeditionary Force” led by Field Marshal Fitzroy Somerset, 1st Baron Raglan. Lord Raglan was a veteran officer of the Napoleonic Wars who had served with distinction on the Duke of Wellington’s staff during the Peninsular War and the Hundred Days. Although he had seen very little combat since the Battle of Waterloo, Raglan remained one of Great Britain’s most experienced commanders, if a rather cautious and indecisive one. Like its Turkish counterpart, the British Army had been bolstered from around 18,000 men to just under 52,000 with the arrival of the 2nd and 3rd Infantry Divisions and the remainder of the Cavalry Division over the Winter. A further two Infantry Divisions (the 4th and Light Divisions) were scheduled to muster later that Spring and would arrive in theater by mid-Summer. There were also several thousand volunteers from across Europe, North Africa and the Levant assisting the Ottomans, with the Poles, Germans, Italians, and Tunisians forming the largest contingents. Even still, the Allied Army in the Balkans barely stood at 200,000 men in the Spring of 1855, many of whom were invalidated by disease or garrisoned in provinces far from the front.

Despite their inferiority in numbers, both Omar Pasha and Lord Raglan favored fighting a field battle against the Russians as they believed that the superior discipline and firepower of their troops would more than make up for their numerical short comings. This belief was vested in the fact that their more advanced weaponry, specifically the Pattern 1852 Enfield Rifle and the 1848 Minié Rifle, would outperform their Russian counterparts. By the Spring of 1855, around 70% of the British Army in the Balkans was equipped with the new Enfield Rifle, whilst more than 30% of the Ottoman Army of Rumelia was touting the Enfield or French made Minié Rifle. In comparison, only 5% of the Russian soldiers possessed rifles and many of these men were in Guard units stationed far away from the front in Bulgaria. Field testing over the previous year had shown that the Enfield rifle had a maximum viable range of nearly 1250 yards and could hit targets with great accuracy from as far away as 900 yards when wielded by a skilled marksman. Similarly, the Minié Rifle used by nearly a third of Omar Pasha’s Army, could hit targets as far out as 1200 yards and could reliably hit a target under 600 paces. In contrast, the Russian M1845 Infantry Musket-Rifle only had a maximum range of 600 paces and was highly inaccurate beyond 300 meters, thus explaining their penchant for bayonet charges.[4]

The British could also outpace their Russian rivals in rate of fire, reliably shooting 4 rounds per minute on average with their Enfields and in some rare instances, firing as many as 5 or even 6 rounds after extensive practice and drilling. The Russians could only manage 2 to 3 rounds per minute on average with their older guns, while the Ottomans could generally shoot between 3 or 4 rounds in a minute with their newer weapons. The ammunition used by the British and Ottomans was also superior to the Russians as they utilized the new Minié ball which held far more destructive potential than the spherical musket ball still used by the Russians. The bullet could rend flesh and shatter bones with ease and still possess enough potency to wound another man on the opposite side. Finally, the British and Ottomans had a moderate advantage in cannons, especially heavier caliber siege guns thanks to such cannons as the rifled Dundas and Lancaster 68-Pounder Guns, and the formidable Millar and Dickson 32-Pounder guns. Although their accuracy was dissapointing, their destructive firepower was capable of terrifying even the most hardened veteran.

The British and Ottoman commanders need not wait long to test their theories as on the 15th of March, Count Paskevich ordered his army out of its winter quarters and into action. Like the previous year, his main objective for this campaigning season would be the fortress city of Silistra, whose capture would open the route south into the Balkans. Their first opponent would be the Danube, however, as Prince Gorchakov’s Army of Wallachia needed to cross the river to join Count Lüders’ Army of Moldavia which had wintered on the left bank of the Danube. This would prove more difficult than expected, as Omar Pasha had razed all the nearby bridges still under his control over the winter (and even some of the bridges held by the Russians). Similarly, the various fords in the region had been fortified by Omar Pasha, depriving Gorchakov of an easy route across the Danube.

Undeterred, Prince Gorchakov ordered the construction of several pontoon bridges across the river, beginning in early March, but once again, Omar Pasha proved his mettle by dispatching several hundred soldiers aboard rowboats to harass the Russian engineers as they were built their bridges. In response, Gorchakov was forced to send out his own boats to counter the Turkish raiders. Their efforts were further hindered by the British heavy siege guns outside Silistra, which peppered the Russian engineers on an hourly basis. Although they missed more shots than they hit, their massive size and power struck fear into the average Russian soldier causing the construction to slow to a crawl.

Fighting on the Danube between Russian and Ottoman Troops

To take pressure off Gorchakov, Count Lüders stirred his

Army of Moldavia from its camp outside Cernavodă and began marching on Silistra several days later on the 24th of March. To his surprise, however, he would find the British Balkan Expeditionary Force and half of the Ottoman Army of Rumelia arrayed against him near the town of Oltina as if inviting an attack. Believing that the British were only good at fighting the savages in their colonies and that the Turks were cowards who would break before the fighting even started, many Russian officers were confident in their looming victory and pressed Lüders to attack the Anglo-Ottoman Army.[5] Lüders complied and order his men to advance.

The Allied position was also quite strong, however, anchored on the left by the Danube and on the right by Lake Oltina, thus mitigating the Russian’s advantage in cavalry. Moreover, this would be one of the few instances in the Great Eurasian War where the Russians would be outnumbered, only fielding 101,398 men and 168 cannons against 51,873 British soldiers and 64,711 Ottoman troops with 234 guns between the two. The British would position themselves on the left side of the road with the 1st and 2nd Infantry Divisions positioned next to each other in the front, while the 3rd Infantry and Cavalry Divisions were held in reserve in the rear. The Ottomans and their Arab allies would form themselves up on their right, with Ahmed Pasha arranging his divisions in three rows of infantry, with their cavalry protecting their flank, and their artillery in the rear alongside the British guns. Opposite them, Count Lüders massed his force in two large columns; 3rd Corps which was standing against the Ottomans and 5th Corps which was counter to the British.

Leading the charge against the British would be the Russian 14th Division which boisterously advanced on the scarlet line of the Guards, Grenadiers and Fusiliers. Once in range of their Enfield Rifles, the Royal Scots Fusiliers, Coldstream Guards, and Royal Grenadiers unleashed a withering volley of leaded death on the charging Russians who fell in heaps upon the ground. They would fire off four volleys before the Russians even made it into range of their antiquated muskets at which point, only getting a single volley off upon their oppressors, who promptly stepped back in the face of the Russian advance. In their place emerged, the mighty men of the Highland Brigade who charged through the Guard’s ranks; bayonets fixed and battle cry raised. Their vicious onslaught broke the wavering Russian line who soon fled the field in a panic.

The Coldstream Guard at the Battle of Oltina

Further down the line the Russian 15th Infantry Division was fairing better against the British 2nd Division, successfully firing off three volleys upon their tormentors, but here too the British proved their superiority, shooting off a blistering 23 rounds in five minutes. The commander of the 2nd, British General George de Evans Lacy had tenaciously drilled his division into an excellent instrument of war, capable of waylaying the Russians as they charged across the field of Oltina. In the face of such a withering cacophony of smoke and lead, the Russians of the 15th Division would begin to crumble and then ultimately break. On the other side of the battlefield, the Ottomans were having more trouble as their outdated guns generally proved inferior to the British Enfields, but those few soldiers with Minié Rifles would manage much better, inflicting a butcher’s bill upon the approaching Russians. Nevertheless, it was apparent that the Russian hammer had fallen the hardest upon the Ottomans.

With his right being driven back in disarray and his left blunted, Count Lüders saw that victory was slipping through his grasp, but still hoping to force a favorable outcome he readied his reserves for battle. Unfortunately for Lüders, the British would make their move first as the Highland Brigade - continuing their earlier charge, followed soon after by the Guards Brigade and 2nd Division - advanced upon the Russians position, guns blazing, cannons blasting, and men roaring. The Russian 9th Infantry Division’s attempt to halt their advance would see it crack in the face of the British rifles. Recognizing that he had lost the initiative, Lüders ordered his remaining troops to break off their attack and withdraw. The Battle of Oltina was over, with upwards of 13,000 casualties for the Russian army, at a cost of only 5,500 dead and wounded for the British and Ottomans.

While Oltina was certainly a solid victory for the Allies, it could have been a much greater triumph as Raglan would make a critical mistake during the battle’s last moments, by refusing to unleash the Light Brigade cavalry on the retreating Russians. Many of his subordinates would later criticize Lord Raglan for this decision, but according to his own report, the British Field Marshal claimed to have seen the similarly unbloodied Russian Cavalry amassed on the far side of the battlefield, ready to ambush the Light Brigade if they made such an attack. Reports by Raglan's deputies refute this however, portraying the Field Marshal as a doddering fool. Regardless of his rationale, Raglan’s decision not to release the Light Brigade on the fleeing Russians enabled them to retreat in good order, turning what could have been a major rout into a moderate defeat at best. Still, had he followed up this victory with an aggressive campaign against Lüders beaten army, Raglan could have inflicted further defeats upon them, likely driving the Russians from Rumelia entirely.

Instead, Lord Raglan delayed pursuing Lüders Army of Moldavia for the better part of a week while he allowed his men time to rest and time for his scouts to recon the Russian position. By the sixth day, Raglan finally decided to advance against Lüders Army encamped west of Cernavodă, but when they arrived on the 3rd of April, he would find that the Russians had been reinforced with an extra division from Paskevich making good all their losses from Oltina and then some. Worse still, while he had been dithering, the Russians under Prince Gorchakov had finally finished the first of their bridges across the Danube, reaching the isle of Păcuiul lui Soare and were now in the process of reducing the isle’s Byzantine fortress to rubble. Despite his best efforts, Omar Pasha’s men were being pushed back, necessitating Raglan's and Ahmed Pasha's withdrawal back to Silistra to aid in its defense. By the 6th of April, the islands northeast of Silistra had fallen to the Russians and the following day, Russian troops began streaming across the Danube en masse; the Second Siege of Silistra had officially begun.

Unlike the First Siege in 1854, the defenses surrounding Silistra had been strengthened immensely over the previous months, with the construction of multiple lines of fieldworks before the city. The first of these lines was the Omar Line, 11 detached forts running in a narrow channel around the city of Silistra, the keystone of which was the impressive Mejidi Tabia, a polygonal fortress in the Prussian style which generally proved itself impervious to all but the heaviest artillery fire. In front of this were several other lines of increasing length and stoutness, the last of which was the Burgoyne line running from the banks of the Danube to the village of Akkadınlar over 20 miles to the south. The left flank of the Allied lines was anchored on the Danube as Omar Pasha’s fleet of river boats impeded any efforts by the Russians to outflank their defenses from the north. The Right end of the Allied line was protected by the British whose position was centered on the twin redoubts Victoria and Wellington.

Perhaps most important to the Allied defense was a rudimentary railroad running southward out of Silistra to the city of Shumen, before jutting eastward to the port of Varna.[6] This single track of rail would be the most significant supply route into and out of the City for the duration of the second siege. Although it was dangerously exposed to Russian raids (hence the considerable effort by the British to defend it), this track would provide an immense boon to the Allied defense of Silistra as it constantly transported men and munitions to the city over the coming months.

Because of this, the battle for Silistra would begin as a war of maneuver as the Russians attempted to turn the Allied flank, pushing further south to in a bid to cut this artery into the city. Efforts by the Russians to turn the Allied flank in the south would meet with resistance, however, as the British troops took up position on the right, guarding their railroad with the utmost ferocity and determination. After a week of continuous cannon bombardment, the Russians would launch an all-out assault on Silistra’s outworks all along the Burgoyne line. Their goal was not to take these positions, however, but to pin down Allied resources in their forts, thus preventing them from aiding the British in the South, where the Russian attack would fall the hardest as the 9th, 14th, 15th, 16th, and 17th Infantry Divisions would be concentrated against the British.

Redoubt Victoria was an impressive sight, however, as it boasted 52 cannons, including all of the British 64-Pounders, and the entirety of the British 2nd Division under the capable command of General George de Lacy Evans. The Russian 14th Division was given the honor of leading the attack, with General Moller personally leading the charge. However, the General’s courage would soon fail him as a British bullet quickly stuck his horse, sending him to the ground in a huff. His wits now lost, Moller requisitioned an aide’s horse and promptly fled to the rear, where he would remain for the remainder of the battle; he would be summarily stripped of his command and removed from active duty the following day. The loss of the Russian commander would not delay the Russian attack, but merely disorganize it as the Russian wave became separated in places, resulting in a piecemeal attack upon the British, who repelled them with relative ease. Not all went well for the British as Lord Raglan would be incapacitated rather early in the battle.

Despite the inherent dangers, Raglan and his aides had perched themselves above the redoubt to get a better view of the battle unfolding before them. [7] The battle very quickly came to him however, as a squadron of Russian Cossacks spotted Raglan's company and charged the careless British Commander. Were it not for the quick action of his guards and aides who intervened to save him, it is likely he would have been captured or killed that day, irreparably harming the British war effort in the Balkans. Instead, he would only suffer a superficial wound that would quickly heal on its own, but would later withdraw to Constantinople for further medical treatment on orders from Whitehall. He would not return to the field again. While he would technically remain in overall command of all British forces in theater, field command was temporarily shifted to Raglan’s Chief of Staff, Sir John Fox Burgoyne before shifting permanently to General George Brown, commander of the Light Division once he arrived in early July.

The Russian attack in the North would meet with more success, as they would succeed in punching through portions of the Burgoyne line. The defenders, after having driven off three prior attacks, were running low on ammunition and were simply exhausted following hours of constant fighting. When the fourth attack came, they bravely held their ground for as long as they possibly could, but gradually gave ground in the face of the overwhelming Russian numbers. Ultimately, with their allies unable to come to their aid and the Russians continuing to pour in, they broke and streamed out of their trenches towards the city of Silistra seeking safety.

The Russian attack in the North would only be halted due to their own poor planning. As the lion's share of their resources had been dedicated further south against the British, they had few if any reserves with which to throw into this unexpected opening in the North. Unable to fully exploit this opportunity, the Russians were soon forced out when the Ottomans and British redirected their reserves to plug this gap in their lines. The Russians of the 10th and 11th Divisions would retreat from the Burgoyne line, carting off the captured cannons, rifles and any captives they had found within.

A second assault two weeks later would yield a similar result, with the Russians making good initial gains, only to be thrown back with heavy casualties. Although these two assaults had failed, Paskevich would determine that Silistra could still be taken by force, but it would likely be done at a high cost in blood and lives. Not wishing to pay such a price at this time, Paskevich and his deputies considered alternatives to this stratagem. Speaking first, Count Lüders proposed bypassing Silistra altogether and advancing on Dobrich from their bases in Dobruja. This proposal would be shot down almost immediately, however, as their supply lines would be jeopardized by an Ottoman controlled Silistra and British naval dominance in the Black Sea. Moreover, Dobrich was a formidable fortress in its own right; implying that an attack against Dobrich would essentially be a repeat of their current situation, but in a far less favorable position. Most importantly though, the Emperor, Tsar Nicholas had explicitly ordered them to take Silistra no matter the cost. Their objective was clear, Silistra must fall.

Gorchakov would then suggest expanding the front to the west of Silistra, thus drawing defenders away from the city. This would work to Russia’s strength of numerical superiority, an advantage that was currently being wasted with their concentration on Silistra, but to do so, they would first need to secure a crossing further upstream. Unfortunately, Omar Pasha had destroyed all the bridges between Călărași and Turnu still under his control, and even a few under Russian occupation were destroyed as well. Similarly, the Ottomans and their allies had gone to great lengths to fortify all the known fords along their stretch of the Danube. For the Russians to cross the Danube upstream of Silistra, they would need to fight their way across, a prospect many did not find appealing, or construct another set of pontoon bridges as they had done in the east. Given the great resistance they had encountered back in March and April spanning Călărași and Păcuiul lui Soare, this strategy was met with skepticism by Paskevich and his staff officers. But, when a third assault on Silistra failed the following week, Paskevich ultimately gave Gorchakov his approval.

Moving decisively, Prince Gorchakov ordered 4th Corps under General Dannenberg to attempt a crossing opposite the city of Oltenița on the 3rd of June. Once in position, they would then advance upon Silistra from the West, whilst the remainder of the Russian Army would attack from the East and North. Faced with an attack from multiple directions, the Allied Army would be destroyed, Silistra would be captured, and the road to the Balkan Mountains would be opened, thus putting Constantinople at great risk. Of course, not everything would go according to plan as Dannenberg’s advance would be slowed by early Summer storms which roiled the Danube, greatly delaying his efforts to cross the river. When they finally began crossing in late June, they would be quickly discovered by local Turkish herders who quickly relayed this information to Omar Pasha and General Burgoyne at Silistra.

Despite this potential disaster, they would be saved by British overconfidence as General Burgoyne dismissed the report out of hand, as there had been several such rumors of a Russian crossing further upstream, all of which had turned out to be false or little more than Cossack raids that were easily repulsed. Omar Pasha would prove more diligent than his British counterpart, however, and dispatched two newly raised brigades to determine the accuracy of this report. Two days later, they would encounter elements of the Russian vanguard west of the village of Popina. Despite their inferior numbers, the Ottomans bravely held their ground and repelled the Russian advance until dusk, at which time Dannenberg arrived with the remainder of his Corps.

Instead of immediately pushing his advantage, however, Dannenberg would delay and dither, choosing to let his own troops rest after their long march and arduous crossing, rather than immediately attack the beleaguered and outnumbered Turks. His caution was worsened by erroneous reports from his scouts that greatly overestimated the size of the Turkish contingent to nearly twice their actual numbers, prompting the General to delay the following day’s attack until mid-day, whilst he formulated a grand battle plan to overcome the supposedly stout Ottoman army opposing him.This delay would enable the Turks to dig in and send word to Omar Pasha requesting reinforcements.

When General Dannenberg finally made his move late in the afternoon of the following day, he would find the Ottoman position bolstered by the arrival of the newly arrived British Light Division which had forced marched through the night to arrive in time for the battle. Despite this, the Russians still greatly outnumbered the British and Ottomans by nearly three to one. Confident in his superior numbers and the elan of his men, Dannenberg readied his soldiers for an attack on the Allied position at mid-day. Dannenberg’s efforts would be for naught however, as the commander of the 10th Infantry Division, Lt. General Soimonov disagreed with Dannenberg's orders and would instead implement his own by attempting a wide flank around the Ottoman position. Yet, in the midst of this maneuver, two of Soimonov's brigades would become lost and march past the battlefield entirely, while the remaining brigade wouldn’t arrive until well after the battle had begun.

This error in judgement was compound by his decision not to inform his counterparts General Pavlov of the 11th Division, and General Liprandi of 12th Division that he was diverging from Dannenberg’s prepared stratagem. With one of their three divisions missing in action for most of the battle, the balance of power between the two forces was evened greatly. Nevertheless, the fight was hard fought on both sides, with the Russians slowly, but steadily advancing and the British and Ottoman soldiers gradually giving ground. The turning point in the battle would come late in the day when a stray bullet struck General Liprandi in the shoulder. In spite of pleas from his lieutenants to withdraw from the front and receive medical attention for his wound, the Russian General continued to lead his men from the front, inspiring them with his bravery and valiance. Moments later, another shot would find its way into his skull, killing him instantly.

Russian Soldiers attacking at Popina

With General Liprandi’s death, command of 12th Division would pass to his deputy General Alexander Friedrichs, but at this time he was several miles from the battlefield and would not arrive on scene until well after nightfall. During this period of time, the 12th was effectively leaderless, and command devolved to its constituent regiment commanders who failed to fill the role of their late leader as they constantly bickered with one another. With their losses continuing to mount and their Generals proving indecisive, the demoralized men of the 12th would ultimately elect to retreat, leaving the 11th to face the Allied Army by itself. Faced with this setback, General Dannenberg ordered General Pavlov to withdrawal his division and promptly dispatched his cavalry to fend off an Allied pursuit. At this late hour, General Soimonov’s men would finally arrive at the battle, but as they were now alone on the battlefield, they were easily cut to pieces by the British and Ottoman sharpshooters, destroying whatever cohesion the unit still had.

Despite the Allied victory at Popina, their position was steadily deteriorating as they simply lacked the men to drive the defeated Russians from their new beachhead. Although initially disappointed at Dannenberg’s setback, Gorchakov’s stratagem had proven its worth and he would soon receive permission to dispatch 2nd Corps to reinforce Dannenberg’s thrust. However, news from the north would disrupt this when elements of the Hungarian Honved Army appeared along the border with Wallachia, as if threatening to attack. Concerned that the Hungarians would intervene against them, Count Paskevich recalled 2nd Corps and redirected it northward to the Carpathian Mountains where it would remain for the better part of the next three months. Now short one Corps, Gorchakov's western offensive came to an untimely end.

With the campaigning season more than half way over and pressure from St. Petersburg building, Count Paskevich turned to Count Lüders’ Army of Moldavia and grimly ordered it to prepare for an advance against Silistra. Lüders stoically accepted his orders and readied his men as best he could for their glum task. Over the next two weeks, the Russian artillery used its entire stockpile of cannonballs upon the Allied lines, firing nearly 320,000 shells to admittedly little effect as many fell short, while others overshot their targets by a mile. The British and Turkish guns in contrast, found their marks more often than not, and would actually outpace their Russian adversaries in number of cannonballs fired at over 40,000 a day. Despite this inauspicious start, the Russian attack would commence at dusk on the 18th of July as Count Lüders ordered his men to advance against the Allied lines and continue their advance until Silistra fell or they perished. Before departing their trenches, many Russian soldiers knelt down to pray and confess their sins to the priests passing through their lines, and in return they received promises of paradise for their service in this holy war. With that, the Russian Army leapt from their holes and marched forward until victory or death.

Aided by the night, the Russians emerged from the darkness unexpectedly and fell upon the helpless British and Ottoman soldiers forcing them into a violent melee. Drunk like demons, they attacked their adversaries. Driven on by their priests and excited by their ardent liquors, the Russian troops rushed forward, beating, bayoneting, bashing, and brutalizing all they found in their path. Some had their heads taken off at the neck, as if they had been removed with an axe. Others were missing their legs or their arms. A few were even hit in the chest or stomach by the British 18 pounders at point blank range, blasting their bodies to bits as if they had been smashed by a machine. In one instance, 5 Russian grenadiers were all killed by one round shot as they charged their enemy. On their faces were a myriad of emotions ranging from anger and rage to sadness and pain. On the fields of Silistra were mountains of dead and dying men, some as old as 50 and others as young as 14.

An hour into the attack, the Russians would finally succeed in taking several parts of the Burgoyne Line, forcing the British and Ottomans to scrape together their invalids and arm them with whatever weapons they could find, before rushing them into battle. This desperate measure would succeed in blunting the Russian assault as exhaustion, illness, and most crucially, a lack of munitions wore down the Russian juggernaut. Even still, they very nearly broke through and by all accounts it is a miracle that the Allied Line held as long as it did.

If the Russians had any more men to throw at the Allies they very likely could have taken Silistra that day, yet Paskevich did not have more men, having sent a quarter of his Army northward to guard against the Hungarians. With the Allied Line holding, albeit barely, and the toll in lives continuing to mount, the Russian soldiers gradually began to lose heart. As dawn broke over Silistra, some exhausted men simply gave up the fight and left the battlefield, followed soon after by more and more of their compatriots. By dawn, the Russian attack evaporated, their soldiers leaving the field in a huff, their officers powerless to stop them.

The battle was over, the Allies had won, but the bloodshed would continue for several more hours as the Turks and their Arab cohorts brutally slaughtered any Russian that they had come across, before looting the dead of all their valuables. The British response would differ only slightly, in that they looted the Russian wounded before leaving them to die at the hands of angry Ottomans or exposure to the elements. Some more charitable Britons would initially offer water and first aid to their wounded adversaries. Yet this philanthropy would not last long as rumors quickly circulated that the Russians were murdering these good men when they went to offer aid. Angered by this, they too would resort to butchering the Russian wounded just like their Turkish counterparts. When the Russians learned of these massacres, they would respond in kind killing the few Ottoman captives they had taken completing the atrocity.

When Paskevich learned of the heavy toll in Russian blood he had paid for a few meters of dirt, he became visibly sick and weak. In the coming days, his condition continued to worsen to the point where he asked the Tsar to relieve him of his post and let him die in peace. The Tsar would initially refuse Paskevich’s request, but on the council of his Chief of Staff Prince Menshikov, he would later reverse his decision, permitting Paskevich to retire with full honors. As this debate was taking place between Count Paskevich and Tsar Nicholas, the fighting in the Balkans slowed to a halt as Paskevich had neither the will nor the fortitude to continue the battle and simply left the matter to his successor. When Paskevich was finally permitted to resign his post on the 13th of October, he handed command of the Army of the Danube over to Prince Gorchakov and retired to his estates in Gomel; he would be dead by the end of the year, likely of some camp sickness he had caught while on campaign. By this late hour, little could be done by Gorchakov before the onset of Winter, but unlike the previous year, the Russian Army would Winter outside Silistra, continuing the siege (albeit sporadically) over the coming months.

Prince Mikhail Dmitievich Gorchakov, 2nd Commander in Chief of the Army of the Danube

Back in the East, however, the fighting was still ongoing as General Muravyov’s siege of Erzincan had met with some success after more than four months. Unable to take the city by storm, Muravyov had been forced to put the city under siege, but as he had abandoned most of his cannons to the muddy roads of Eastern Anatolia, he was forced to blockade the city and starve its defenders into submission. Unfortunately, the city had been well stocked with food and munitions prior to the Russians arrival giving them the strength to resist for some time. Yet, by early September, the defenders’ will to fight was nearly exhausted as help was nowhere to be seen and their supplies were running out. Some even considered surrendering the city to the Russians if help did not come soon.

Conditions in the Russian camp were not good either as their numerical advantage soon became a hindrance for the Russian Army as its lines of supply were quite long and dangerously exposed to raids by Ottoman irregulars hiding in the surrounding hills and valleys. Muravyov’s attempts to counter these attacks met with little success as the raiders simply retreated into the surrounding mountains when the Russians approached en masse, then returned to harass the Russian stragglers when the Army turned away. By September, Muravyov’s army was starved of bullets and gunpowder, while Food was fast becoming an issue as the surrounding countryside had been desolated after four months of scavenging and looting.

The arrival of Mehmed Rushdi Pasha and an Ottoman 46,000 strong on the 22nd would complicate matters for the beleaguered Russians as it bolstered the resolve of Erzincan's defenders and concerned Muravyov's exhausted men. However, this show of force by Rushdi Pasha was little more than an illusion. His host was not an army of veteran soldiers, but a mob of greybeards and fresh faced youths, irregulars and bandits. A few had rifles, most had antiquated muskets, while some didn't even have that, often wielding pikes or swords. Most of the Ottoman troops had very little if any formal military training and their discipline was nonexistent. Rushdi Pasha knew all this and thus refrained from picking a fight with Muravyov, instead erecting fieldworks and hoping to attrite the Russians into withdrawing. Muravyov would have none of it, however, and readied his men to fight.

The Battle of Erzincan would be surprisingly evenly fought engagement despite the differences in troop quality as the exhausted Russian soldiers flung themselves at the relatively fresh recruits of the Ottoman Army. The end result was never in doubt, however, as the Russians slowly and methodically pushed the Turks back until finally they broke and fled the field. With the defeat of Rushdi Pasha's relief army, the city of Erzincan lost its last remaining hope of rescue and surrendered to the Russians the following morning, thus removing the last Ottoman bastion in the Erzurum valley.

With Erzincan now under his control, General Muravyov moved to solidify his gains in the region before the end of the campaigning season. As such, the coming days and weeks would be spent occupying remote hilltop villages and securing the roads across the Erzurum Valley which fell almost entirely under Russian control. The Fall of Erzurum, followed by the fall of Erzincan was a disaster for the Sublime Porte, who was now forced to recall its troops from Georgia and Armenia. Mehmed Pasha's army was forced to abandon its gains in Abkhazia and Mingrelia, before retreating to the Eyalet of Trabzon, which now came under threat from both the East and the South. Similarly, Ali Pasha's army was recalled from Akhaltsike and positioned between Mehmed Pasha and Rushdi Pasha's armies. Finally, the remnants of Selim Pasha's host were ordered to defend Northern Mesopotamia. Overall, the Ottoman Army had less than 80,000 men stationed across the Pontic Mountains to Sivas and from Sivas to Lake Van.

Muravyov's attempts to push westward and secure the mountain passes to Sivas in late October would be repulsed however, as Rushdi Pasha had reformed his green force and entrenched itself near the village of Refahiye in the easterly foothills of the Anatolian Plateau. While the Russian Army could have likely taken theses passes on a second assault, the strength of the Russian army had been thoroughly sapped after eight months of constant fighting and hard marching. Nearly a third of its number lost to disease, desertion, and battle, while many thousands more were stuck garrisoning the newly conquered cities and towns across Eastern Anatolia. Moreover, Muravyov's supply lines were at their limits as munitions and food were increasingly scarce. With winter only a few weeks away, General Muravyov had no choice but to halt his offensive; this was as far as he would advance this year.

By all accounts, 1855 had not been a good year for the Russian Empire as they suffered great losses and terrible setbacks on almost every front, whilst the one front they did achieve success on was greatly dimmed by the cost in men and material needed to attain it. Neither was it the great triumph that the British and Ottomans needed, as they had failed to attract powerful allies to their side in the fight against Russia. Nor had they followed up on their battlefield successes with offensives of their own, which might have forced Russia onto the defensive. Instead, they had allowed Russia time to recover and regroup, and when the campaigning season in 1856 arrived the Russian Bear would be poised to get its revenge.

Next Time: Desperate Measures

[1] A similar incident happened in OTL, during the Russian siege of Kars.

[2] The more I look into it, the more I discover just how bad the supply situation for the Russian Army in the OTL Crimean War really was. Of the 1.2 million troops listed on the rolls of the Imperial Russian Army, only around 5% had rifles, most of which were prescribed to members of the Life Guards. In contrast, more than 50% of the British troops possessed rifles during the OTL Crimean War. ITTL, I would probably say its even higher for the British owing to the extra year of preparation by the British, putting it somewhere around 60 to 70%. Worse still, according to the official stocks of the Imperial Russian Army, they only had enough guns for around half their listed troops when the war started in 1853. These shortages weren’t limited to rifles as carbines and pistols were also in short supply. There also appears to have been a rationing of ammunition prior to the war, with the average soldier only receiving 10 rounds per year for training. I would assume it would be higher during the war, but I haven’t found anything definitive on this. That being said, the Tsarist Government would likely prioritize their units in the Balkans, the Baltic, and the Caucasus over those in Central Asia and the Far East, alleviating their shortages somewhat. Even still, they fall incredibly short of the British material advantage who could fire close to 100,000 cannonballs with regularity during the final stages of the OTL Siege of Sevastopol.

[3] The Ottomans and British were also affected to a lesser degree, with roughly 1 in 10 suffering from one disease or another.

[4] I’m pretty sure the Russian weapon used during the Crimean War was a muzzle loading musket, but the Russian sources I’m using refer to it as a rifle.

[5] Ironically, British propaganda depicted the Russians as savages. So, if anything, this would be a backhanded compliment for the British.

[6] Interesting, the British had constructed a similar railroad from Balaclava to their camp overlooking Sevastopol in the OTL Crimean War to improve their supply situation, which this railroad achieves as well. Obviously, this railroad is much longer than the OTL one, but I’m handwaving this thanks to it being built in friendly territory and Britain having to pick up the slack that France held in OTL, which largely takes the form of engineers and technicians. I’m also giving the British more time to build it, about 4-5 months as opposed to the

7 weeks it took them to build the dual track railroad in OTL.

[7] A similar incident very nearly happened in OTL during the battle of Alma. There, Raglan rode ahead of the Army to scout out the battle, but in doing so very nearly came under fire from Russian gunners.