I really need to think of different fonts for this

Vivian Tan, The Government of Sarawak; Past and Present (Kayangan Publishing: 1992)

The Sarawak that emerged from the crises of the 1850's was a far cry from the land that James Brooke first set foot on in 1839. Though battered by rebellions and nipped of territories by the Dutch, the adventurer-state came out from the period paradoxically stronger and robust than before. In the face of superior weaponry and skills, most of the insurrectionists either surrendered to Brooke forces or left the nation entirely, either moving deeper into the Bornean interior, across the river deltas into Brunei, or up the mountains into Dutch territory.

Besides this, the rebellions and tangentially related Borneo Treaty also taught the miniscule Sarawak government several new lessons; that the kingdom would need an elite fighting force to nip future rebellions from blossoming; for greater discussion between chieftains, lords, and the European Residents of the land; and – most importantly – that whatever future lands gained must be immediately settled and built-up with to prevent future partitions. These lessons and way in which they were implemented would, in time, form the backbone of the nation today and still influence Sarawak’s relations with the outside world.

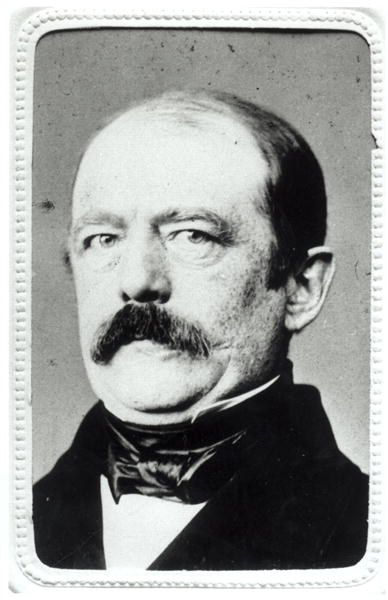

The first of these lessons would be encapsulated in 1862 when the new Rajah Muda of Sarawak (Charles Brooke) authorised the creation of an elite paramilitary force that could act as "special operatives in situations of combat". The force, known as the Sarawak Rangers, were composed of a selection of Manok Sabong – fighting men from the Iban subgroup, handpicked by the Residents and the Brooke family from various longhouse villages. The selected men were then grouped together and put under the command of a British officer to, as written by the first Ranger commander Henry Rodway, "...[to] protect the borders, man strategic forts, and fight any rebels that run afoul of them."

In lieu of Rajah James’s Romanticism (though some would say pragmatism), the selected Dayaks were asked not to abandon their native styles of fighting. In fact, they were instead asked to amalgamate British weaponry and fighting skills with that of their own, as well as providing input on jungle warfare with their overseers. This would result in a mixed combat approach that lended well to the thick jungles and swamps of Borneo. As the decades passed, the Sarawak Rangers would expand its force to include Bidayuhs, Kayans, Malays and even a few Sikhs, each group adding to the repertoire new combat options and styles, and each adding to the Rangers' overall effectiveness in irregular conflict situations. In time, this elite fighting force would sow the seeds of the modern Royal Sarawak Army...

Another lesson learned from the era was the need for greater communication between the region's multiple overlords. While the Residency system of European Residents, native officers, and local lords and chieftains did resolve all but the greatest conflicts on the local level, they were helpless against large regional rebellions such as those of Libau Rentap and Sharif Masahor. In addition, the different needs of the kingdom's Divisions during the 1850's began showing themselves in lopsided growth for the overall state, with more resources being diverted to one particular area at the expense of others. In the wake of this, a forum for discussion at the state level was sorely required.

The answer to this problem would be twofold in nature. First, the Kuching government redrew the Divisons of Sarawak with an added ruling that larger administrative areas can have two or more Residencies to better administer the land. The other solution took a longer time to be thought of, and even longer to be executed. In the end though, it's implementation would sow in the kingdom the seeds to not just modern governance, but representative governance...

Temenggung Jugah Anak Barieng, Early Sarawak: 1846-1868 (Kenyalang Publishing, 2000)

Though battered and bruised, Sarawak made it through the instability of the 1850's in a much more stable position then it had been, and none of this was more exemplified than the way the kingdom improved itself during the 1860's.

With the major rebellions of the past decade now largely over and with the Borneo Treaty settling –for now – the question of the Sentarum Floodplains, the Kuching administration now focused itself on paying back its creditors from which it owed large amounts of money to, a laborious process that would continue until the end of the decade. Both the government and the White Rajahs borrowed large sums of cash in trying to combat the rebellions as well as building up the infrastructure of Kuching village, a process that had to be repeated when the 1857 Uprising burned most of the administrative buildings to the ground.

The servicing of debt would strain the kingdom's finances back to levels resembling the beginning years of the state, though the discovery of coal near the town of Simunjan in 1863 did brought much needed revenue for the balance sheets. Several of the creditors such as Baroness Burdett-Courts also offered a partial write-down of the debts they incurred, further reducing the strain on the country. Despite all these measures, the Kingdom of Sarawak in the early 1860's was more cash-strained than it would ever be for the rest of the 19th century.

Aside from debt servicing, the administration also began looking at other ways of defending itself. Both Rajah James and Rajah Muda Charles realized that a native fighting force was sorely needed to combat future uprisings from spiralling out of control. From this way of thought would the Sarawak Rangers be created; a paramilitary force that could man strategic forts, patrol the kingdom's borders, conduct jungle warfare effectively, and – above all – gain the trust of the local populace. Local Dayak tribes would make up this new fighting force, later supplemented with Malays and Sikhs as the kingdom grew in size and complexity.

It was also during this era that Sarawak would gain the first of her ships and gunboats, forming the basis of her riverine and maritime fleet. From the very start, the kingdom had to rely on gunboats and merchant vessels either borrowed from the Royal Navy or loaned from sympathetic shipping figures. However, as the debt situation began to clear up in the mid-1860's the Kuching government began purchasing several shipping vessels and riverine gunboats outright, rebranding them as the new possessions of the upstart nation. While the number of gunboats and shipping vessels owned was paltry compared that of its closest neighbour, British Singapore, the Kingdom of Sarawak can – for the first time – finally boast of having a (miniscule) fleet of her own.

But perhaps one of the greatest achievements of this decade – and one that would mark the kingdom’s transition into a full-fledged state – was not an economical shift but an administrative one. The unrest of the past decade saw the need for greater communication between the Residents and the kingdom's inhabitants, a need that was further highlighted when the Kuching government uncovered the lopsided growth of the nation's Divisions. However, it wouldn’t until 1867 when Rajah Muda Charles finally tackled the problem by convening an assembly of European Residents, Malay lords and Dayak chieftains to discuss major issues. However, in a land dominated almost entirely by wild rainforests and uncharted territory, such an order seemed near-impossible to execute.

Despite it all, a meeting was eventually chaired, though it was a far cry from the grand assembly Rajah Muda Charles wanted. On September 7th 1867, Charles Brooke, 5 British officers, 16 Malay lords and a handful of Melanau chieftains all convened at the town of Bintulu, forming the first session of the Council Negri. The meeting was supposed to discuss national matters and offer collective advice for the Kuching government and the White Rajahs, as well as acting as a rubber stamp for the Brooke government’s policies.

However, as time passed the Council Negri would slowly evolve into more than just an advisory assembly…

Charlie MacDonald, Strange States and Bizzare Borders (weirdworld.postr.rom, 2014)

Okay, at this point you'd probably be thinking "Wait a sec, I can see the Dayaks getting duped by this, but why aren't the Malays doing anything? Can't they see that their "ruler" is not from their country at all!? They're not even Muslims for crying out loud! Why aren't they rebelling!? GARBLHGARBLHGARBLE!!1!1"

Okay, number one: never do that in public, it's indecent.

And number two, no one pretended that the Brookes were locals. Everyone could see that their rulers were all foreigners, and people did question why they are ruled by a non-Muslim family. The thing is...everyone at the time was kinda 'meh' about it all, and aside from a few people who did rebel, the Malays were kinda OK with being ruled. Before you scream again, you need to understand that people living in Sarawak at the time had vastly different priorities than people living today.

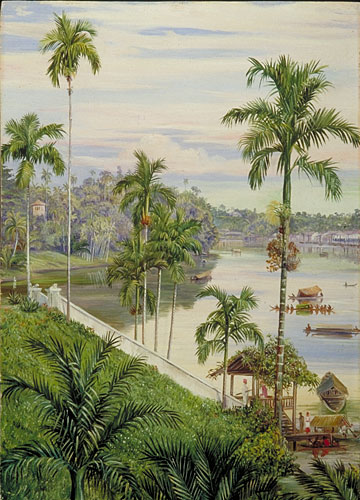

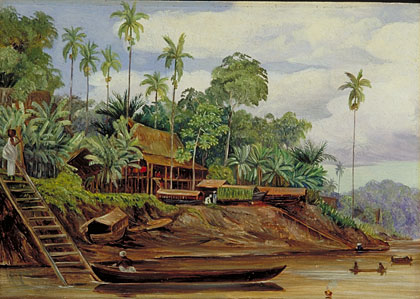

Let's think of it this way: imagine you are a Malay fruit-seller living in a riverside village. You have a farm and a fruit orchard that you depend on for cash, and you have a small business selling them to other villages downstream. However, your fruit-selling business is kinda uncertain due to climate factors and all, and that's not including the Dayaks that roam the river a few times a year. Usually their war Perahus just pass your village as they head downstream, but sometimes they land on your home and demand fruits to so that your head wouldn't be cut off. You also pay taxes to the local Bruneian official, who may or not overtax you (different parts, different tax rates) and who may or may not pocket the money for himself.

All in all, your life could've been way better. And that's exactly what the Brookes did.

Now imagine the White Rajah coming to village on a boat, flanked by Dayaks and Malay warriors. Speaking in Malay (Wow, a foreigner who speaks Malay! He understands us!), he tells you and your village that he would try to make your life here better and wants your co-operation in making this dream. All he asks is for some warriors to join him against the head-hunters and that you now pay taxes to his official instead of that Bruneian oaf instead. You ask what happened to the Bruneian oaf, the man answers that he has been fired from his job.

At first, it seemed as if nothing changed. You sell your fruits, row your boat, do the normal things most Malays do... then you begin to notice it; your tax rates are a bit lower than before, and there are no more warring Dayaks to bribe fruit to. In fact, most of the Dayaks who came down here now are of the trading sort, not the 'cutting-heads-off' rabble, and they wanna trade with your village offering goods from the jungle for your own wares. You also begin to notice more and more people travelling the rivers; with less war expeditions it's now safer to travel for everyone. You take advantage of this and began selling the fruits to the wayfarers, and your business grows.

And this was repeated, for the most part, throughout all of Sarawak. Brooke rule meant safe rule, and the Malays knew this more than anyone else. Also, most of their lords and headmen were already involved in governing the country alongside the Residents, so it wasn't as if they were entirely sidelined in the new order. The Brookes also didn't try and convert them to Christianity, earning them major points from the locals (though not so much for the Dayaks).

To be fair, a few Malay villages did rebel against this, seeing that they simply traded one overlord for another (the Brookes being non-Muslims might've played a factor as well). However, they almost never lasted long and were always defeated by the White Rajah and his new army. Besides that, there were many villages that refused to pay taxes for the first few years because they were uncertain of their new European Residents.

In the end though, almost everyone slept better in the night because of the new security the White Rajahs brought...and no one wanted to change that (although the jury is out on attempted burglary and murder; that's the village's problem, not the Brookes).

__________

Footnotes:

1) The Council Negri was an actual body of the government that convenes European Residents, Malay lords and Dayak chieftains about once every three years that basically acts as a giant discussion group and rubber stamp for the White Rajahs. A monument still exists in Bintulu that commemorates the first meeting.

2) Yes, the Sarawak Rangers were an actual thing.

Vivian Tan, The Government of Sarawak; Past and Present (Kayangan Publishing: 1992)

The Sarawak that emerged from the crises of the 1850's was a far cry from the land that James Brooke first set foot on in 1839. Though battered by rebellions and nipped of territories by the Dutch, the adventurer-state came out from the period paradoxically stronger and robust than before. In the face of superior weaponry and skills, most of the insurrectionists either surrendered to Brooke forces or left the nation entirely, either moving deeper into the Bornean interior, across the river deltas into Brunei, or up the mountains into Dutch territory.

Besides this, the rebellions and tangentially related Borneo Treaty also taught the miniscule Sarawak government several new lessons; that the kingdom would need an elite fighting force to nip future rebellions from blossoming; for greater discussion between chieftains, lords, and the European Residents of the land; and – most importantly – that whatever future lands gained must be immediately settled and built-up with to prevent future partitions. These lessons and way in which they were implemented would, in time, form the backbone of the nation today and still influence Sarawak’s relations with the outside world.

The first of these lessons would be encapsulated in 1862 when the new Rajah Muda of Sarawak (Charles Brooke) authorised the creation of an elite paramilitary force that could act as "special operatives in situations of combat". The force, known as the Sarawak Rangers, were composed of a selection of Manok Sabong – fighting men from the Iban subgroup, handpicked by the Residents and the Brooke family from various longhouse villages. The selected men were then grouped together and put under the command of a British officer to, as written by the first Ranger commander Henry Rodway, "...[to] protect the borders, man strategic forts, and fight any rebels that run afoul of them."

In lieu of Rajah James’s Romanticism (though some would say pragmatism), the selected Dayaks were asked not to abandon their native styles of fighting. In fact, they were instead asked to amalgamate British weaponry and fighting skills with that of their own, as well as providing input on jungle warfare with their overseers. This would result in a mixed combat approach that lended well to the thick jungles and swamps of Borneo. As the decades passed, the Sarawak Rangers would expand its force to include Bidayuhs, Kayans, Malays and even a few Sikhs, each group adding to the repertoire new combat options and styles, and each adding to the Rangers' overall effectiveness in irregular conflict situations. In time, this elite fighting force would sow the seeds of the modern Royal Sarawak Army...

Another lesson learned from the era was the need for greater communication between the region's multiple overlords. While the Residency system of European Residents, native officers, and local lords and chieftains did resolve all but the greatest conflicts on the local level, they were helpless against large regional rebellions such as those of Libau Rentap and Sharif Masahor. In addition, the different needs of the kingdom's Divisions during the 1850's began showing themselves in lopsided growth for the overall state, with more resources being diverted to one particular area at the expense of others. In the wake of this, a forum for discussion at the state level was sorely required.

The answer to this problem would be twofold in nature. First, the Kuching government redrew the Divisons of Sarawak with an added ruling that larger administrative areas can have two or more Residencies to better administer the land. The other solution took a longer time to be thought of, and even longer to be executed. In the end though, it's implementation would sow in the kingdom the seeds to not just modern governance, but representative governance...

**********

Temenggung Jugah Anak Barieng, Early Sarawak: 1846-1868 (Kenyalang Publishing, 2000)

Though battered and bruised, Sarawak made it through the instability of the 1850's in a much more stable position then it had been, and none of this was more exemplified than the way the kingdom improved itself during the 1860's.

With the major rebellions of the past decade now largely over and with the Borneo Treaty settling –for now – the question of the Sentarum Floodplains, the Kuching administration now focused itself on paying back its creditors from which it owed large amounts of money to, a laborious process that would continue until the end of the decade. Both the government and the White Rajahs borrowed large sums of cash in trying to combat the rebellions as well as building up the infrastructure of Kuching village, a process that had to be repeated when the 1857 Uprising burned most of the administrative buildings to the ground.

The servicing of debt would strain the kingdom's finances back to levels resembling the beginning years of the state, though the discovery of coal near the town of Simunjan in 1863 did brought much needed revenue for the balance sheets. Several of the creditors such as Baroness Burdett-Courts also offered a partial write-down of the debts they incurred, further reducing the strain on the country. Despite all these measures, the Kingdom of Sarawak in the early 1860's was more cash-strained than it would ever be for the rest of the 19th century.

Aside from debt servicing, the administration also began looking at other ways of defending itself. Both Rajah James and Rajah Muda Charles realized that a native fighting force was sorely needed to combat future uprisings from spiralling out of control. From this way of thought would the Sarawak Rangers be created; a paramilitary force that could man strategic forts, patrol the kingdom's borders, conduct jungle warfare effectively, and – above all – gain the trust of the local populace. Local Dayak tribes would make up this new fighting force, later supplemented with Malays and Sikhs as the kingdom grew in size and complexity.

It was also during this era that Sarawak would gain the first of her ships and gunboats, forming the basis of her riverine and maritime fleet. From the very start, the kingdom had to rely on gunboats and merchant vessels either borrowed from the Royal Navy or loaned from sympathetic shipping figures. However, as the debt situation began to clear up in the mid-1860's the Kuching government began purchasing several shipping vessels and riverine gunboats outright, rebranding them as the new possessions of the upstart nation. While the number of gunboats and shipping vessels owned was paltry compared that of its closest neighbour, British Singapore, the Kingdom of Sarawak can – for the first time – finally boast of having a (miniscule) fleet of her own.

But perhaps one of the greatest achievements of this decade – and one that would mark the kingdom’s transition into a full-fledged state – was not an economical shift but an administrative one. The unrest of the past decade saw the need for greater communication between the Residents and the kingdom's inhabitants, a need that was further highlighted when the Kuching government uncovered the lopsided growth of the nation's Divisions. However, it wouldn’t until 1867 when Rajah Muda Charles finally tackled the problem by convening an assembly of European Residents, Malay lords and Dayak chieftains to discuss major issues. However, in a land dominated almost entirely by wild rainforests and uncharted territory, such an order seemed near-impossible to execute.

Despite it all, a meeting was eventually chaired, though it was a far cry from the grand assembly Rajah Muda Charles wanted. On September 7th 1867, Charles Brooke, 5 British officers, 16 Malay lords and a handful of Melanau chieftains all convened at the town of Bintulu, forming the first session of the Council Negri. The meeting was supposed to discuss national matters and offer collective advice for the Kuching government and the White Rajahs, as well as acting as a rubber stamp for the Brooke government’s policies.

However, as time passed the Council Negri would slowly evolve into more than just an advisory assembly…

**********

Charlie MacDonald, Strange States and Bizzare Borders (weirdworld.postr.rom, 2014)

Okay, at this point you'd probably be thinking "Wait a sec, I can see the Dayaks getting duped by this, but why aren't the Malays doing anything? Can't they see that their "ruler" is not from their country at all!? They're not even Muslims for crying out loud! Why aren't they rebelling!? GARBLHGARBLHGARBLE!!1!1"

Okay, number one: never do that in public, it's indecent.

And number two, no one pretended that the Brookes were locals. Everyone could see that their rulers were all foreigners, and people did question why they are ruled by a non-Muslim family. The thing is...everyone at the time was kinda 'meh' about it all, and aside from a few people who did rebel, the Malays were kinda OK with being ruled. Before you scream again, you need to understand that people living in Sarawak at the time had vastly different priorities than people living today.

Let's think of it this way: imagine you are a Malay fruit-seller living in a riverside village. You have a farm and a fruit orchard that you depend on for cash, and you have a small business selling them to other villages downstream. However, your fruit-selling business is kinda uncertain due to climate factors and all, and that's not including the Dayaks that roam the river a few times a year. Usually their war Perahus just pass your village as they head downstream, but sometimes they land on your home and demand fruits to so that your head wouldn't be cut off. You also pay taxes to the local Bruneian official, who may or not overtax you (different parts, different tax rates) and who may or may not pocket the money for himself.

All in all, your life could've been way better. And that's exactly what the Brookes did.

Now imagine the White Rajah coming to village on a boat, flanked by Dayaks and Malay warriors. Speaking in Malay (Wow, a foreigner who speaks Malay! He understands us!), he tells you and your village that he would try to make your life here better and wants your co-operation in making this dream. All he asks is for some warriors to join him against the head-hunters and that you now pay taxes to his official instead of that Bruneian oaf instead. You ask what happened to the Bruneian oaf, the man answers that he has been fired from his job.

At first, it seemed as if nothing changed. You sell your fruits, row your boat, do the normal things most Malays do... then you begin to notice it; your tax rates are a bit lower than before, and there are no more warring Dayaks to bribe fruit to. In fact, most of the Dayaks who came down here now are of the trading sort, not the 'cutting-heads-off' rabble, and they wanna trade with your village offering goods from the jungle for your own wares. You also begin to notice more and more people travelling the rivers; with less war expeditions it's now safer to travel for everyone. You take advantage of this and began selling the fruits to the wayfarers, and your business grows.

And this was repeated, for the most part, throughout all of Sarawak. Brooke rule meant safe rule, and the Malays knew this more than anyone else. Also, most of their lords and headmen were already involved in governing the country alongside the Residents, so it wasn't as if they were entirely sidelined in the new order. The Brookes also didn't try and convert them to Christianity, earning them major points from the locals (though not so much for the Dayaks).

To be fair, a few Malay villages did rebel against this, seeing that they simply traded one overlord for another (the Brookes being non-Muslims might've played a factor as well). However, they almost never lasted long and were always defeated by the White Rajah and his new army. Besides that, there were many villages that refused to pay taxes for the first few years because they were uncertain of their new European Residents.

In the end though, almost everyone slept better in the night because of the new security the White Rajahs brought...and no one wanted to change that (although the jury is out on attempted burglary and murder; that's the village's problem, not the Brookes).

__________

Footnotes:

1) The Council Negri was an actual body of the government that convenes European Residents, Malay lords and Dayak chieftains about once every three years that basically acts as a giant discussion group and rubber stamp for the White Rajahs. A monument still exists in Bintulu that commemorates the first meeting.

2) Yes, the Sarawak Rangers were an actual thing.

Last edited: