Robert Whitlam, The Farthest Colonies: Fiji and New Caledonia (Queensland Bowen Press; 1991)

…the proposal for Fiji to become the new base of British operations in the Pacific wasn’t met with enthusiasm, especially from Australia. This was mostly due to circumstance; the newly-formed federation practically salivated at crushing the French bases and Italian warships docked at New Caledonia and the New Hebrides. But with spilt priorities over Papua, Southeast Asia, and the Indian Ocean, the dominion was reluctant to commit what meagre naval resources they had left to yet another maritime expanse. Instead, it was New Zealand who picked up the slack though not before haranguing her reluctant neighbour on the dangers of commerce harassment, particularly from Noumea.

As such, it was Wellington that footed the bill in soldiers and supplies when approval was ultimately granted by the Admiralty. When the cyclone season subsided in May 1906, it was mostly New Zealanders and a token Maori contingent that struck out to Fiji. Arriving to the main island of Viti Levu, they wasted no time in calling up local Europeans, Indo-Fijians, and even some natives to pitch-in the war effort, retrofitting the harbour of Suva to counter a future French attack. Said attack would come surprisingly faster than expected in a surprise assault on June 1st. Under the cover of dawn, two French gunboats and one Italian frigate attempted to bombard the harbour and take the port, only to be fended off by the established New Zealander contingent – though not without some cost to several British and New Zealand gunboats.

Seeing this result – and swallowing some racial hang-ups – Melbourne finally began stepping up commitment to the Pacific theatre. And chief among their concerns was New Caledonia.

With such a lucrative and strategic French base so close to the continent, it was not a surprise to find the federation eyeing the mountainous island. By 1900, New Caledonia was suppling nearly 10% of the world’s nickel demand alone from local deposits, to say nothing of the land’s potential for forestry and cash-crop agriculture. Given Australian racial sentiment, it was also not surprising that there was a racial component for having the island; Australian newspapers throughout 1905 and 1906 printed tall tales from travelling idiots and former sailors, detailing how colonial Frenchmen are training the local Kanak population to become an invasion force for the Third Republic – a racist imagining of the country’s invasion paranoia.

However, the island possessed another equally undesirable trait: a large underclass of foreign prisoners. As a penal colony, New Caledonia saw the internment and forced labor of tens of thousands of rabble-rousers from the French metropole and its far-flung colonies. The convict population was largely heterogeneous, but there were two large groups that overshadow the rabble: leftist radicals, and Algerian fighters.

Normally, these groups would have found much to disagree with one another, but time and distance had smoothed relations to the point that around half of the 5000 Algerian prisoners on the island have intermarried by 1906, forming new families with their fellow convicted neighbours. Given these groups’ opposition to the French, it wasn’t long before British intelligence (or more precisely, Australian spies) focused on this underclass. [1] Several spies sneakily ensconced themselves in Noumea throughout the southern winter after sailing from secret ships, surreptitiously establishing contact with the natives and convict-settlers.

A detailed sketch of the three types of the New Caledonian underclass: A Kanak farmer, a convict-settler, and an Algerian Arab or Amazigh rebel.

It was also a fortune that, this far into 1906, the belligerent colony of Italian Papua had been bombed of working ports (though interior control was still elusive) [2a.] and the Southeast Asian naval theatre had mostly concluded [2b.], while the production of new warships at Sydney harbour ran at full speed, leaving the British dominions with enough firepower to finally match the speedy French and Italian gunboats.

On August 28th 1906, New Caledonia was awoken to the sound of artillery and exploding vessels as a dual force of British and Australian men – and a tripartite force of both nations’ navies and that of New Zealand’s – landed on the north end of the island. On the sea, the combined might of the British Empire pounded on the floating fortresses that protected the isle, proving once and for all that the French and Italian doctrine of emphasising speed and manoeuvrability as per the Jeune Ecole doctrine came at a cost of lighter, weaker hulls. As 5 French and 2 Italian warships began to sink at Banare Bay, the decision was made among the remaining naval command at Noumea to abandon the island and save whatever warships remained. By the following day, the entire northern half of the island was under occupation. By August 30th, the remaining Franco-Italian fleet disappeared into the Pacific expanse, sailing to French Polynesia.

To the relief of the French planters and mining class, the new administration did not confiscate their estates and firms – the joint occupation force was willing to bury any revenge grumblings so long as they pledged new allegiances and allowed the export of nickel for the British war effort (though this didn’t stop several Frenchmen from refusing cooperation and getting booted as a result). The same magnanimity did extend to the non-islanders, whom make up the bulk of New Caledonia’s population. A sizable portion of these were the non-criminal workers of the island’s nickel mines, whom were contracted from as far away as Indochina, the New Hebrides, and the Dutch East Indies. For them, life changed little as they worked for a pittance in supplying nickel ore to the foundries and factories of Australia.

The island’s true criminal underclass was a much different – and divided – affair. For the socialists, communists, anarchists, and Algerian independence convicts, exiled to the remotest penal colony of the French Empire, the new occupation force was uncertain on how they should be treated. As purveyors and instigators of radical thought, they were seen as less trustworthy and given to toe the new line. On the other hand, it was feared that clamping down on them would risk fermenting an island-wide uprising. A proposal to deport all penal criminals to the Australian mainland was floated, only to be scrapped when it was met with an enraged home public. One columnist to the Melbourne broadsheet, The Argus, warned that allowing such an order would, quote; “…flood Australian land with duplicitous radicals and violent mohammedans, which will not stop at nothing to poison Australian minds with their ideas which sanctify the destruction of human progress”.

Rare French postcard of convict-settlers harvesting cash crops on New Caledonia, sent just before the Australian takeover of the island

As for the Kanaks, their conditions were the sorriest. The racism of mainland Australian society, which was notorious even then, quickly reared its head and made itself home against the indigenous inhabitants. Building on French laws, Kanaks continued to be excluded from formal work and education while the Kanak language was officially banned from public use; anyone caught speaking it, even if they were French citizens, would face ruinous fines and imprisonment. The indigenous inhabitants of the land were ultimately confined to mountainous reservations that only covered 10% of New Caledonia, depriving them of any opportunities for advancement or even full movement.Still, as the island became a part of Australia in all but name, and as the French-controlled New Hebrides fell just 48 hours after the surrender of Noumea, the new masters failed to recognize that the closeness of the underclass with one another, with some even forming families, would led to the hybridization of radical ideas…

********************

Petru Nuñez, A History of Pacific Wars; The Great War, SW Cornellia: 1989)

…The entry of Germany into the Great War not only changed the balance of power in the Oceania theatre, but also placed an awkward wrench to Australia and New Zealand’s plans.

From the British dominions’ point of view, the Pacific Ocean was supposed to be their sphere of influence. With mining and plantation concerns proven to be profitable across the island chains, both Melbourne and Wellington sought a piece of the profits. Defence also played a role, as both Australia and New Zealand believed they were at risk if the Pacific islands are held by any other power than Great Britain; a fear that became reality as French and Italian commerce raiders stalked the reefs and atolls. In a secretive twist, New Zealand sought to grab a Pacific empire of her own to counterbalance the commercial and military might of Australia, which is why Fiji today is more closely aligned to the south rather than to the west. [3]

But Germany declared war on France, and thus upended their plans.

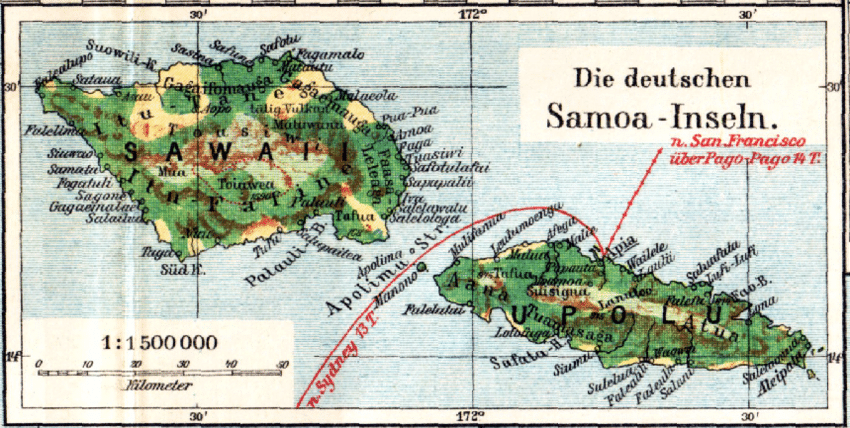

The French navy, with their knack for speed, tried to strike first by claiming the colony of German Samoa. What they hadn’t counted was the arrival of the German East Asia Squadron, a branch of the imperial navy that was stationed in the Papuan colony of Kaiser-Wilhelmsland. Steaming quickly into the Pacific (their offer of naval aid against New Caledonia and the New Hebrides was pointedly rebuffed by an irate Australia) [4] they reached the Samoa islands just as the French were attacking them. The German flag was actually in the process of being hoisted down at the capital of Apia when the squadron arrived, creating an awkward situation for the French sailors overseeing the event. Recalling the day, the island’s German governor Wilhelm Solf remarked; “…I don’t know whether to laugh at my surrender and reinstatement – to be fired and re-hired in 30 minutes! The crowd of onlookers was more amused than confused that day.”

The German navy quickly stepped-up their mantle by capturing the French islands of Wallis and Futuna, which neighboured Samoa. This did not come without cost, though, with one warship sunk and 2 more heavily damaged as the remaining French and Italian vessels fled.

German propaganda print of ‘The Last Sailor’ who stayed behind as his ship went down at Wallis and Futuna. In actuality, such a scene never happened.

This unwelcome introduction into the nature of Pacific warfare would bedevil the squadron just as it had for the Royal Navy and the dominions of Australasia. Now with more players in the front, the disparate warships, gunboats, and commerce raiders of the Marine Nationale and the Regia Marina would settle on a new tactic: ambush raids and cat-and-mouse night battles, often near neutral ports and territories. By the end of the southern winter, the areas of conflict have shifted to around Spanish Micronesia for the west, French Polynesia and Chile at the east, and Hawaii as the perennial middle zone of war and peace. Commerce raiding, hit-and-run shelling, and ambush attacks became the new norm for any British or German merchant mariner traversing these regions, and the unfavourable formation of grouped convoys – already in use since last year – became more pronounced for these territories.

Even for the British and German-held islands, the situation was far from secure. The Gilbert and Ellice Islands became notorious for sudden raids, while the German colony of Nauru saw scenes of sudden night attacks that damaged both phosphate extraction and communications equipment. Even the New Hebrides saw one spectacular cargo raid in late October by the Italian cruiser Oddone Eugenio that left even the rear admiral of the newly formed Royal Australian Navy, William Rooke Creswell, impressed. “I would’ve given them praise if they were mine own men”, he said privately after hearing of the raid.

But the high point of French and Italian chaos in the Pacific was beginning to wane. The conclusion of naval theatres elsewhere and the full production of warships in Australia and Canada began to tip the scales of firepower, which coincided with the slowdown of warship construction in France, Italy, and Imperial Russia from supply problems. Additionally, both the Hawaiian and Spanish Philippine governments were getting annoyed both at the antics happening on their waters and of the complaints by the Four Powers to close their ports to belligerent shipping. Already, there were reports of brawls erupting between sailors of different nationalities in Manila and Oahu, and there is pressure to update shore leave laws to intern such instigators, regardless of diplomatic fallouts.

While the vastness of the Pacific Ocean still eludes complete control, and while the Cook Islands and the Pitcairns are still under French control, the speedy warships of the Patras Pact are being whittled down, one by one…

Sailors of the Kriegsmarine re-raising the German flag at Apia, 3 minutes after the French tried to lower it down.

Notes:

This whole piece was originally supposed to be appended to the previous Africa instalment, but I decided to make it its own thing as the Pacific theatre unfurled beyond my estimations.

Perhaps one of the greatest POD’s not-to-be in this region are the recruitment of local Fijians into the Great War effort. IOTL, they helped in the taking and occupation of German colonies in the Pacific and a Native Fijian Contingent even served in Europe, turning heads wherever they went. With the Pacific still in flux, there might not be a chance to have indigenous Fijians serve in the fronts there, more’s the pity.

1. This is just a repeat of Post #1492, but it does bear mentioning.

2. Refer to Post #1434 for the situation in Italian Papua (2a.) and the conclusion of the South China Sea naval theatre (2b.).

3. The result of an enlightening long-ago conversation with @SenatorChickpea. Surprisingly, New Zealand had imperial ambitions of having a Pacific empire of its own during the mid-to-late 19th century. As early as 1865, the future Premier of the dominion, Julius Vogel, published a pamphlet that espoused, in short: “…Samoa, Tonga, Fiji and the New Hebrides as component parts with New Zealand of a Pacific Confederation.” By the 1870s, reports are drawn up that surveyed every major Pacific island chain – noting population, natural resources, best harbours, and the like.

4. Never mess with a nation that has invasion paranoia and a perception for claiming nearby islands as rightfully theirs. This was a sore point for many Australian citizens even in OTL. Invasion literature was a noticeable thing (that Wikipedia page needs serious updating) and the 1907 Imperial Conference saw the Australian Prime Minister, Alfred Deakin, urging the British to focus more on Pacific matters.

2. Refer to Post #1434 for the situation in Italian Papua (2a.) and the conclusion of the South China Sea naval theatre (2b.).

3. The result of an enlightening long-ago conversation with @SenatorChickpea. Surprisingly, New Zealand had imperial ambitions of having a Pacific empire of its own during the mid-to-late 19th century. As early as 1865, the future Premier of the dominion, Julius Vogel, published a pamphlet that espoused, in short: “…Samoa, Tonga, Fiji and the New Hebrides as component parts with New Zealand of a Pacific Confederation.” By the 1870s, reports are drawn up that surveyed every major Pacific island chain – noting population, natural resources, best harbours, and the like.

4. Never mess with a nation that has invasion paranoia and a perception for claiming nearby islands as rightfully theirs. This was a sore point for many Australian citizens even in OTL. Invasion literature was a noticeable thing (that Wikipedia page needs serious updating) and the 1907 Imperial Conference saw the Australian Prime Minister, Alfred Deakin, urging the British to focus more on Pacific matters.

Last edited: