You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Of Rajahs and Hornbills: A timeline of Brooke Sarawak

- Thread starter Al-numbers

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 145 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Perkahwinan of the Rajah: mini-afterword Mid-Great War: 1906 - Arabian Peninsula Mid-Great War: 1906 - Africa Mid-Great War: 1906 - Oceania 1906 summary: part 1 / 2 1906 summary: part 2 / 2 Interlude: An Eclipse of Change (1907) Late-Great War: 1906-1907 - East Asia and the Russian Far EastOkay, due to me starting my university courses, I'm officially putting the timeline on hiatus (semi-hiatus? time will tell). As much as I want to write about Brooke Sarawak and Sabah and how will it affect the wider world, there's just a lot of real life work to do for me to concentrate on this thing. I might update once in a while, but I don't think I'll be as active as before until the end of the year. Sorry for letting you all down.

Stay curious, everyone.

What chr92 said.No letting down at all. You've already done a great job. Thank you. Good luck with the university.

Though we will be glad when you do continue.

The last years of Rajah James

Officially moved from Hiatus to Semi-Hiatus!

Temenggung Jugah Anak Barieng, Early Sarawak: 1846-1868 (Kenyalang Publishing, 2000)

In the mid-19th century, and especially so in rural South East Asia, surviving a stroke was considered lucky, and surviving a second stroke was even more so. When James Brooke entered through a third episode on his sixtieth birthday and yet still lived, it was nothing short of a miracle to the Sarawakians.

However, as the decade went on the extent of the damage began to show on the White Rajah. The series of strokes left the statesman greatly impaired in both mobility and health, forcing him to delegate affairs of state to his heir apparent, Charles. When his personal physician decided on a trip back to England for further treatment and rehabilitation in 1866; no one doubted he would never come back to the kingdom he had built, not alive at least. When James finally left his residence for good on January 18th, thousands of Kuching residents and numerous Dayaks from the surrounding forest flocked to the banks of the Sarawak River, trying to catch a glimpse of their ruler for the last time.

By then, the Kingdom of Sarawak was a land transformed. Over two decades ago, the region was nothing more than a neglected part of the Sultanate of Brunei. By James Brooke's departure, it was a growing, thriving independent state that had beaten impossible odds and numerous setbacks to become one of the most thriving polities in the region, at least when compared to its neighbouring states. The kingdom had its own functioning government, administration, civil service and even a small cadre of emissaries, making it a rising player in Bornean affairs and a regular correspondent with its colonial neighbours, Great Britain and the Kingdom of the Netherlands.

Alongside governance came basic infrastructure. By 1866, Sarawak had a postal service, a currency (tied to the Straits Dollar) and a shipping fleet of its own, both for trade and defensive purposes. The capital of Kuching, once ravaged by the uprising of 1857, was rebuilt into a town that many explorers and contemporaries described as one of the most picturesque in all of Borneo, featuring brick and timber shophouses and tropical-retouched government buildings. Development also began making way to the surrounding rainforest in the form of churches, dirt roads, and bridges, though much of Sarawak would remain wild and untamed for the rest of the 19th century.

Lithograph of a missionary church in Lundu, one of the very few towns that were allowed missionary work by the Sarawak government.

Besides roads and offices, Sarawak had also improved on the art of war and peace by the time of James’ departure. Alongside forming the Sarawak Rangers – whose duties now include border patrol along certain sections of the Sarawak-Dutch border, the government also relegated certain coastal and riverine villages with tax exemptions so long as they provide useful men as auxiliary troops on Dayak campaigns. Besides that, traditional peacekeeping ceremonies became adopted by the Brooke government, with James Brooke or the Residents attending Dayak gatherings and even participating in local festivities to help foster useful alliances. Moreover, a system of river forts located throughout the kingdom also kept check against any recalcitrant upriver tribes.

With physical change came social change, some more deeply felt than others. For the Malays of the capital, the White Rajah's choice of wanting educated locals as administrators opened many doors, though most had to educate themselves on basic English to better understand their superiors (a situation that drastically increased the attendance rate of nearby missionary schools). The local lords and ex-nobles of Brunei were also fully incorporated into the kingdom by the late 1860's, filling the gap between the rule of the Residencies and the local environment of which they governed. There was also the change of bettering themselves through enlistment in the Sarawak Rangers, though few took up the offer until the 1870's.

Wife of a retired Sarawak official with grandchildren, circa 1871

For the Chinese, the evolution of Sarawak had also been largely positive. The government's policy of cottage industries and unwillingness to get foreign investors involved often meant that Chinese traders were the only ones that had enough capital (and credit) to conduct business within the kingdom. Merchants from Canton and Hainan quickly established themselves on the larger towns, trading with the locals on everything from rattan furniture to porcelain cups. A small number of immigrants also began settling in the river deltas to grow cash crops such as pepper and gambir, adding to the kingdom’s revenues. However, since the uprising of 1857 the Sarawak government also took some harsh measures against the community, particularly against Chinese secret societies (otherwise known as kongsi) for which any inclusion or affiliation was punished severely.

As for the Dayaks, their reaction to Brooke Sarawak was the most tumultuous of all, and the effects of Rajah James’ rule were felt very disproportionally across the land. However, in general:

• For the Bidayuh, the close proximity of the capital to their lands meant that they were among the first to transport whatever food and supplies needed downstream, making them useful allies.

• For the Iban, Sarawak was the petrol that set their homeland in flames, accelerating conflicts and tearing apart old traditions.

• For the Melanau, the state was a useful protector against piracy and a valuable outlet for their traditional industry.

Yet even within this, there were more transformations. Some individual Dayaks became traders in their own right, making money to enrich both themselves and their associated villages. The introduction of taxation also meant many villages had to farm or create something that could be of value to sell, leading to an expansion of existing trades. By 1868, there was a noticeable increase in swidden agriculture, timber production, traditional cloth-making, rattan collecting, wild rubber harvesting, and much more. On the whole though, Dayak society remained largely tribal and there were many villages that were shielded from the outside world, encouraged to a part by the Brooke family.

An Iban woman spinning wild tree cotton into thread using a traditional device, circa 1891

And in a roundabout way, the Brooke family were perhaps the ones that were most transformed by the Kingdom of Sarawak. It is important to remember that, in the beginning, James Brooke originally wanted to create a thriving port city with himself as governor, akin to Stamford Raffles and his colony of British Singapore. However, as Sarawak grew the English adventurer found himself gradually becoming enamoured of his new role as absolute ruler of an entire nation, a role no doubt helped by the local populace who viewed him as a powerful and influential figure – which he was, but not as awesome as they thought.

A major example of this is how Rajah James adopted native Malay titles to better integrate himself with the Sarawak Malays, among which was the adoption of the style Sri Paduka Duli Yang Maha Mulia Rajah dan Yang di-Pertuan Negara Sarawak – His Royal Highness the Rajah and Head of State of Sarawak, a style normally reserved for the rulers of neighbouring Brunei. He also didn't discourage the residents of Kuching from calling his place of residence the Astana (a variant of the word ‘Palace’ in Malay) nor did he stop his native subordinates from calling him "Tuan Rajah" on council meetings, an address that became naturally ingrained among Sarawakians. By the late 1860's even the European residents began addressing the man as either "Sir" or "Your Highness", reflecting James's status as a true monarch in the region.

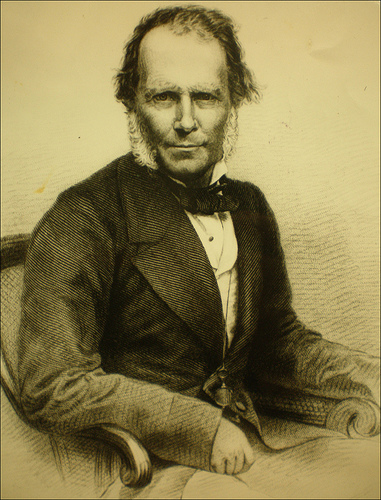

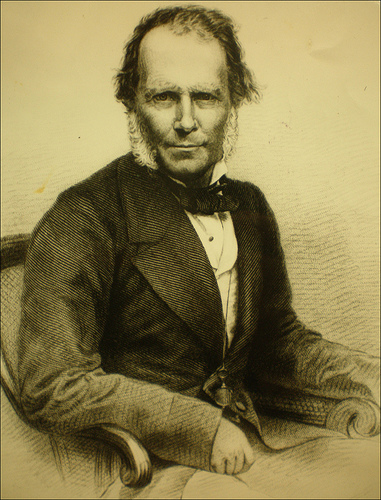

Preserved drawing of Rajah James Brooke, circa 1865

However, for all the positive changes brought by Sarawak there were still a bounty of problems that plagued the evolved nation. Apart from Kuching and the mining towns, almost all of Sarawak remained undeveloped, with river forts being the only sign that the surrounding rainforest belonged to the White Rajahs. What towns that were developed lacked many infrastructural needs and even the capital suffered a few problems of its own; Kuching will not have a proper sewer system well until 1888, and a continuous water supply until 1903. In the vast rainforests and deltas, much of village life – both Malay and Dayak – remained unchanged while most of the upriver and mountain regions elude exploration. Whatever Dayaks that refused Brooke rule fled into these remote places, causing a slew of diplomatic problems for the kingdom and their Dutch neighbours.

However, and even with its defects in consideration, there was no doubt that the formation of Sarawak was an incredible journey for both the nation and the men who oversaw it. The kingdom battled itself against rebellion, foreign intrigue, and insurmountable odds to become a true Bornean Power, as well as laying the groundwork for Charles Brooke and his improvements to the Kingdom of Sarawak, both in territory and other matters. As the ageing James Brooke breathed his last in the south of England in 1868, he still received letters of encouragement and hope from Kuching, a reminder that though the man is gone, he was never forgotten.

The Kingdom of Sarawak at the time of James Brooke’s death at June 11, 1868

Temenggung Jugah Anak Barieng, Early Sarawak: 1846-1868 (Kenyalang Publishing, 2000)

In the mid-19th century, and especially so in rural South East Asia, surviving a stroke was considered lucky, and surviving a second stroke was even more so. When James Brooke entered through a third episode on his sixtieth birthday and yet still lived, it was nothing short of a miracle to the Sarawakians.

However, as the decade went on the extent of the damage began to show on the White Rajah. The series of strokes left the statesman greatly impaired in both mobility and health, forcing him to delegate affairs of state to his heir apparent, Charles. When his personal physician decided on a trip back to England for further treatment and rehabilitation in 1866; no one doubted he would never come back to the kingdom he had built, not alive at least. When James finally left his residence for good on January 18th, thousands of Kuching residents and numerous Dayaks from the surrounding forest flocked to the banks of the Sarawak River, trying to catch a glimpse of their ruler for the last time.

By then, the Kingdom of Sarawak was a land transformed. Over two decades ago, the region was nothing more than a neglected part of the Sultanate of Brunei. By James Brooke's departure, it was a growing, thriving independent state that had beaten impossible odds and numerous setbacks to become one of the most thriving polities in the region, at least when compared to its neighbouring states. The kingdom had its own functioning government, administration, civil service and even a small cadre of emissaries, making it a rising player in Bornean affairs and a regular correspondent with its colonial neighbours, Great Britain and the Kingdom of the Netherlands.

Alongside governance came basic infrastructure. By 1866, Sarawak had a postal service, a currency (tied to the Straits Dollar) and a shipping fleet of its own, both for trade and defensive purposes. The capital of Kuching, once ravaged by the uprising of 1857, was rebuilt into a town that many explorers and contemporaries described as one of the most picturesque in all of Borneo, featuring brick and timber shophouses and tropical-retouched government buildings. Development also began making way to the surrounding rainforest in the form of churches, dirt roads, and bridges, though much of Sarawak would remain wild and untamed for the rest of the 19th century.

Lithograph of a missionary church in Lundu, one of the very few towns that were allowed missionary work by the Sarawak government.

Besides roads and offices, Sarawak had also improved on the art of war and peace by the time of James’ departure. Alongside forming the Sarawak Rangers – whose duties now include border patrol along certain sections of the Sarawak-Dutch border, the government also relegated certain coastal and riverine villages with tax exemptions so long as they provide useful men as auxiliary troops on Dayak campaigns. Besides that, traditional peacekeeping ceremonies became adopted by the Brooke government, with James Brooke or the Residents attending Dayak gatherings and even participating in local festivities to help foster useful alliances. Moreover, a system of river forts located throughout the kingdom also kept check against any recalcitrant upriver tribes.

With physical change came social change, some more deeply felt than others. For the Malays of the capital, the White Rajah's choice of wanting educated locals as administrators opened many doors, though most had to educate themselves on basic English to better understand their superiors (a situation that drastically increased the attendance rate of nearby missionary schools). The local lords and ex-nobles of Brunei were also fully incorporated into the kingdom by the late 1860's, filling the gap between the rule of the Residencies and the local environment of which they governed. There was also the change of bettering themselves through enlistment in the Sarawak Rangers, though few took up the offer until the 1870's.

Wife of a retired Sarawak official with grandchildren, circa 1871

For the Chinese, the evolution of Sarawak had also been largely positive. The government's policy of cottage industries and unwillingness to get foreign investors involved often meant that Chinese traders were the only ones that had enough capital (and credit) to conduct business within the kingdom. Merchants from Canton and Hainan quickly established themselves on the larger towns, trading with the locals on everything from rattan furniture to porcelain cups. A small number of immigrants also began settling in the river deltas to grow cash crops such as pepper and gambir, adding to the kingdom’s revenues. However, since the uprising of 1857 the Sarawak government also took some harsh measures against the community, particularly against Chinese secret societies (otherwise known as kongsi) for which any inclusion or affiliation was punished severely.

As for the Dayaks, their reaction to Brooke Sarawak was the most tumultuous of all, and the effects of Rajah James’ rule were felt very disproportionally across the land. However, in general:

• For the Bidayuh, the close proximity of the capital to their lands meant that they were among the first to transport whatever food and supplies needed downstream, making them useful allies.

• For the Iban, Sarawak was the petrol that set their homeland in flames, accelerating conflicts and tearing apart old traditions.

• For the Melanau, the state was a useful protector against piracy and a valuable outlet for their traditional industry.

Yet even within this, there were more transformations. Some individual Dayaks became traders in their own right, making money to enrich both themselves and their associated villages. The introduction of taxation also meant many villages had to farm or create something that could be of value to sell, leading to an expansion of existing trades. By 1868, there was a noticeable increase in swidden agriculture, timber production, traditional cloth-making, rattan collecting, wild rubber harvesting, and much more. On the whole though, Dayak society remained largely tribal and there were many villages that were shielded from the outside world, encouraged to a part by the Brooke family.

An Iban woman spinning wild tree cotton into thread using a traditional device, circa 1891

And in a roundabout way, the Brooke family were perhaps the ones that were most transformed by the Kingdom of Sarawak. It is important to remember that, in the beginning, James Brooke originally wanted to create a thriving port city with himself as governor, akin to Stamford Raffles and his colony of British Singapore. However, as Sarawak grew the English adventurer found himself gradually becoming enamoured of his new role as absolute ruler of an entire nation, a role no doubt helped by the local populace who viewed him as a powerful and influential figure – which he was, but not as awesome as they thought.

A major example of this is how Rajah James adopted native Malay titles to better integrate himself with the Sarawak Malays, among which was the adoption of the style Sri Paduka Duli Yang Maha Mulia Rajah dan Yang di-Pertuan Negara Sarawak – His Royal Highness the Rajah and Head of State of Sarawak, a style normally reserved for the rulers of neighbouring Brunei. He also didn't discourage the residents of Kuching from calling his place of residence the Astana (a variant of the word ‘Palace’ in Malay) nor did he stop his native subordinates from calling him "Tuan Rajah" on council meetings, an address that became naturally ingrained among Sarawakians. By the late 1860's even the European residents began addressing the man as either "Sir" or "Your Highness", reflecting James's status as a true monarch in the region.

Preserved drawing of Rajah James Brooke, circa 1865

However, for all the positive changes brought by Sarawak there were still a bounty of problems that plagued the evolved nation. Apart from Kuching and the mining towns, almost all of Sarawak remained undeveloped, with river forts being the only sign that the surrounding rainforest belonged to the White Rajahs. What towns that were developed lacked many infrastructural needs and even the capital suffered a few problems of its own; Kuching will not have a proper sewer system well until 1888, and a continuous water supply until 1903. In the vast rainforests and deltas, much of village life – both Malay and Dayak – remained unchanged while most of the upriver and mountain regions elude exploration. Whatever Dayaks that refused Brooke rule fled into these remote places, causing a slew of diplomatic problems for the kingdom and their Dutch neighbours.

However, and even with its defects in consideration, there was no doubt that the formation of Sarawak was an incredible journey for both the nation and the men who oversaw it. The kingdom battled itself against rebellion, foreign intrigue, and insurmountable odds to become a true Bornean Power, as well as laying the groundwork for Charles Brooke and his improvements to the Kingdom of Sarawak, both in territory and other matters. As the ageing James Brooke breathed his last in the south of England in 1868, he still received letters of encouragement and hope from Kuching, a reminder that though the man is gone, he was never forgotten.

The Kingdom of Sarawak at the time of James Brooke’s death at June 11, 1868

Last edited:

The King is dead. Long Live the King!!!! Looking forward to what the Kingdom of Sarawak would be like under the rule of Rajah Charles Brooke. I also look forward to the resolution of the American Borneo debacle and/or the future territorial disputes with the Dutch. Please write more soon. Thank you.

The King is dead. Long Live the King!!!! Looking forward to what the Kingdom of Sarawak would be like under the rule of Rajah Charles Brooke. I also look forward to the resolution of the American Borneo debacle and/or the future territorial disputes with the Dutch. Please write more soon. Thank you.

Let's just say Charles Brooke's Sarawak will be a lot more different than OTL. Existing in a neighborhood coveted by just about every European power will do some things to you.

As for American Borneo, the resolution of that is well near in sight, though I might update on a few things around the world beforehand. The Dutch are going to be... well, the Dutch, but as again there might be few changes to Dutch Borneo down the line, especially when the outside world begins to take notice of the East.

If swidden agriculture is used to produce cash crops, then there could be problems down the line with overuse of land - probably not in the 19th century, given the volume of land involved, but certainly in the 20th.

It should be interesting to see how the state develops under Charles Brooke - he's obviously had an increasing role in government for some time, but now he won't be under James' supervision. The monarchy seems to have become somewhat "Sarawakian" under James; I wonder if Charles will continue that, or if he'll play up its European aspects (which might be useful when contending with colonial powers), or a bit of both.

It should be interesting to see how the state develops under Charles Brooke - he's obviously had an increasing role in government for some time, but now he won't be under James' supervision. The monarchy seems to have become somewhat "Sarawakian" under James; I wonder if Charles will continue that, or if he'll play up its European aspects (which might be useful when contending with colonial powers), or a bit of both.

That is one very rare portrait of James Brooke in his late years. Most sources only show his more youthful self in his dashing 30s when he first came to Sarawak.

Amazed that you managed to find it.

Amazed that you managed to find it.

Apologies for the late replies, everyone.

Thanks!

May he rule the waves for all eternity~

At this point, most of the increase in swidden agriculture is for the production of local crops, which are needed for trade with other tribes and the Malay towns downriver. The real profit-making venture around this period would be wild rubber harvesting (something that I probably need to address sometime in the future, along with it's effects).

However, the overuse of land will be a long-term concern, and a few Bidayuh and Iban tribes are beginning to notice just how profitable growing cash crops would be, especially when the Chinese plantation migration kicks in soon. Hopefully Sarawak would have modernized enough to do something about it when the problem gets major, but there might be a few turns along the way.

It's going to be a fine balancing act, that's for sure. Charles Brooke knows that the power of the White Rajahs stems from being relatable to the Sarawak peoples (attending festivities, holding meetings with chieftains, balancing local laws with foreign ones, etc; ) and having the biggest guns around (gunboats, native warriors, etc; ). However, he also knows that East Asia won't remain an unexplored region for long and that most European powers would think of his rule as just plain odd, not to mention the fact that Borneo would make a nice stoppover point for China...

It's a fine needle, but with his head, Charles might just be able to thread it.

It's a bit hidden, but there are a few photos and drawings of James Brooke in his later years floating around the internet. Most of them are found in Malaysian, Bruneian, and Indonesian websites, so I guess that's why most people can't seem to find them.

Possibly Johor and mayybe Italy and/or Belgium's colonial adventures for the next update. It's about time to look a bit at what's going on around Borneo.

Good update, sketchdoodle!

Thanks!

Thus passes the swashbuckler....

May he rule the waves for all eternity~

If swidden agriculture is used to produce cash crops, then there could be problems down the line with overuse of land - probably not in the 19th century, given the volume of land involved, but certainly in the 20th.

At this point, most of the increase in swidden agriculture is for the production of local crops, which are needed for trade with other tribes and the Malay towns downriver. The real profit-making venture around this period would be wild rubber harvesting (something that I probably need to address sometime in the future, along with it's effects).

However, the overuse of land will be a long-term concern, and a few Bidayuh and Iban tribes are beginning to notice just how profitable growing cash crops would be, especially when the Chinese plantation migration kicks in soon. Hopefully Sarawak would have modernized enough to do something about it when the problem gets major, but there might be a few turns along the way.

It should be interesting to see how the state develops under Charles Brooke - he's obviously had an increasing role in government for some time, but now he won't be under James' supervision. The monarchy seems to have become somewhat "Sarawakian" under James; I wonder if Charles will continue that, or if he'll play up its European aspects (which might be useful when contending with colonial powers), or a bit of both.

It's going to be a fine balancing act, that's for sure. Charles Brooke knows that the power of the White Rajahs stems from being relatable to the Sarawak peoples (attending festivities, holding meetings with chieftains, balancing local laws with foreign ones, etc; ) and having the biggest guns around (gunboats, native warriors, etc; ). However, he also knows that East Asia won't remain an unexplored region for long and that most European powers would think of his rule as just plain odd, not to mention the fact that Borneo would make a nice stoppover point for China...

It's a fine needle, but with his head, Charles might just be able to thread it.

That is one very rare portrait of James Brooke in his late years. Most sources only show his more youthful self in his dashing 30s when he first came to Sarawak.

Amazed that you managed to find it.

It's a bit hidden, but there are a few photos and drawings of James Brooke in his later years floating around the internet. Most of them are found in Malaysian, Bruneian, and Indonesian websites, so I guess that's why most people can't seem to find them.

Possibly Johor and mayybe Italy and/or Belgium's colonial adventures for the next update. It's about time to look a bit at what's going on around Borneo.

Was just reading some scientific articles on the web and I noticed the Krakatoa eruption is just around the corner in 1883. I don't know how major natural disasters like these are covered by AH writers due to all the potential butterflies, but surely you can't just butterfly away a major cyclic eruption like this one, perhaps give or take a few years, or even decades (still considered an insignificantly short time for a volcano).

Anyway, I know Sarawak is quite far from Krakatoa and virtually untouched by the tsunamis, thanks to Sumatra and Java shielding Sarawak from harm. http://factsanddetails.com/media/2/20120529-Krakatoa_Tsunami_1883.jpg

And it'll be the DEI's problem to deal with the aftermath, but still close enough that you might want to consider the eruptions impact on the local climate and crop productions, as well as how the Dayaks interpret such a disaster on the Brooke rule.

Anyway, I know Sarawak is quite far from Krakatoa and virtually untouched by the tsunamis, thanks to Sumatra and Java shielding Sarawak from harm. http://factsanddetails.com/media/2/20120529-Krakatoa_Tsunami_1883.jpg

And it'll be the DEI's problem to deal with the aftermath, but still close enough that you might want to consider the eruptions impact on the local climate and crop productions, as well as how the Dayaks interpret such a disaster on the Brooke rule.

Oh no, I have absolutely no intention of butterflying natural disasters (except for weather-related ones) in this TL. Considering the awesome force of Krakatoa, I don't think I could even try to change it if I could. Most - if not all - of OTL's great natural disasters shall also happen ITTL, and their effects on the TL shall be as great as their real-world aftermaths. Krakatoa's great eruption will come, and there will be a lot of effects on both it and it's surrounding regions.

However, considering the human butterflies already fluttering through the TL, we might see a different cast of characters being affected by the eruption; the Beyerincks might not be in Ketimbang, and there might not be a Governor General Loudon in the volcano's vicinity. There might be a whole new set of experiences being formed by the eruption though, and the catastrophe might affect more than just Dutch Java and Sumatra, people-wise.

However, considering the human butterflies already fluttering through the TL, we might see a different cast of characters being affected by the eruption; the Beyerincks might not be in Ketimbang, and there might not be a Governor General Loudon in the volcano's vicinity. There might be a whole new set of experiences being formed by the eruption though, and the catastrophe might affect more than just Dutch Java and Sumatra, people-wise.

Just read #1 Post

great so far

If you need history or translation of Malay I will be glad to help.

Thanks!

Bosporus Strait, The Ottoman Empire, 1 August 1866.

“And miss the view from this deck?” answered Abu Bakar jovially, noticing his friend behind him. “Come, Jaafar! Come! Let’s wash our eyes after seeing nothing but days of blue sea. We might not even see this view in our farewell trip!”

To get to Istanbul, the ship would pass through the Dardanelles, and before that among the Aegean Islands. They would have seen land many times recently.

If everything goes according to plan, I shall be back in Washington by mid-September and discuss my future position with the foreign policymakers of the city.

"policymaker" sounds very anachronistic. When composing "period" text, it's often good to check usage with Google ngrams. (I can't use it myself due to obsolete browser.)

To get to Istanbul, the ship would pass through the Dardanelles, and before that among the Aegean Islands. They would have seen land many times recently.

Yeah, I realized that about two weeks after I wrote that scene. Abu Bakar was seriously interested in knowing how other countries run, especially the European empires, and having a scene like that would not be really implausible for him (in OTL, he would later modernize Johor based on what he saw in Europe in 1866). If I could rewrite updates, I would have rewritten that. Sorry. [/QUOTE]

"policymaker" sounds very anachronistic. When composing "period" text, it's often good to check usage with Google ngrams. (I can't use it myself due to obsolete browser.)

...Yeah, I have no idea how I put that in. Thanks for the tip, by the way.

Johor and the beginnings of Italian colonialism next up! Probably by this weekend.

Also, does anyone know any interesting things happening in Europe in 1878? I plan to have Abu Bakar go on a royal tour again.

Well, if it's not butterflied away, there'd be a war ongoing between Russia and the Ottoman Empire...Also, does anyone know any interesting things happening in Europe in 1878? I plan to have Abu Bakar go on a royal tour again.

Well, if it's not butterflied away, there'd be a war ongoing between Russia and the Ottoman Empire...

Ooh! That's actually going to be one of the biggest butterflies in this timeline. I plan to have the Ottomans win the war (think Nasirissimo's With the Crescent Above Us) but I'm probably going to do an indirect update about that; maybe a newspaper article or a diary entry. I'm damn clueless on writing war updates, especially on European wars.

With the Ottomans winning the war and returning to Great Power-(ish) status, I can see Abu Bakar establishing closer relations with Sultan Abdul Hamid to ensure Johor's independence (though it's going to be a fine line with British Singapore close by. A visit to Queen Victoria could resolve that, or not) and provide another outlet for the sultanate's exports.

Then again, Sultan Abdul Hamid supported Pan-Islamism whilst Abu Bakar was an Anglophile, so that could be problematic. Besides that, An independent-(ish) Johor is bound be in conflict with an independent Aceh (of which it's sultan would probably go to Konstantiniyye to ensure independence too) sooner or later over their positions on the Straits of Malacca. The fact that both sultanates are pepper and mining exporters doesn't help.

Hmm... anything other than that?

Ooh! That's actually going to be one of the biggest butterflies in this timeline. I plan to have the Ottomans win the war (think Nasirissimo's With the Crescent Above Us) but I'm probably going to do an indirect update about that; maybe a newspaper article or a diary entry. I'm damn clueless on writing war updates, especially on European wars.

With the Ottomans winning the war and returning to Great Power-(ish) status, I can see Abu Bakar establishing closer relations with Sultan Abdul Hamid to ensure Johor's independence (though it's going to be a fine line with British Singapore close by. A visit to Queen Victoria could resolve that, or not) and provide another outlet for the sultanate's exports.

Then again, Sultan Abdul Hamid supported Pan-Islamism whilst Abu Bakar was an Anglophile, so that could be problematic. Besides that, An independent-(ish) Johor is bound be in conflict with an independent Aceh (of which it's sultan would probably go to Konstantiniyye to ensure independence too) sooner or later over their positions on the Straits of Malacca. The fact that both sultanates are pepper and mining exporters doesn't help.

Hmm... anything other than that?

We export pepper too... So make it three...

We export pepper too... So make it three...

True, but the amunt that Johor and Aceh exported was just ENORMOUS. I remember reading somewhere a while back that the pepper exports of both sultanates combined account for over 40% to 50% of the entire world's supply. We grew pepper, but Johor and Aceh produced it as if they were factories.

For Johor (and Sarawak) to get ahead of their neighbours, they need another way to make cash, both to modernize fully and to make themselves important enough for others to listen... and I think I know how.*

*it starts with an r and ends with an r.

Threadmarks

View all 145 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Perkahwinan of the Rajah: mini-afterword Mid-Great War: 1906 - Arabian Peninsula Mid-Great War: 1906 - Africa Mid-Great War: 1906 - Oceania 1906 summary: part 1 / 2 1906 summary: part 2 / 2 Interlude: An Eclipse of Change (1907) Late-Great War: 1906-1907 - East Asia and the Russian Far East

Share: