You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Of Rajahs and Hornbills: A timeline of Brooke Sarawak

- Thread starter Al-numbers

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 145 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Perkahwinan of the Rajah: mini-afterword Mid-Great War: 1906 - Arabian Peninsula Mid-Great War: 1906 - Africa Mid-Great War: 1906 - Oceania 1906 summary: part 1 / 2 1906 summary: part 2 / 2 Interlude: An Eclipse of Change (1907) Late-Great War: 1906-1907 - East Asia and the Russian Far EastI seriously need to keep up with Japanese games and pop-culture.You know, this TL made my brain spin: WI this TL fusioned into GATE? Have the Alnus Gate opened on OTL Legislative Assembly building?

On another note, I sincerely apologize to everyone who's been waiting for an update. Work and other stuff delayed any writing of sorts till the last few weeks, and even then it's been slow going. Rest assured, the next update is being written (hint: it'll involve a certain puritanical religious movement) and I'll try to post it as soon as possible. Cheers!

Mid-Great War: 1906 - Arabian Peninsula

‘Safiat Almajhul’, Arabia: A Complicated History (Silverback Press: 1975)

…In retrospect, it should not be surprising that the Arabian Peninsula was primed for espionage and revolt.

Home to different branches of Islam whose adherents have launched sporadic uprisings and rebellions across Ottoman history, it wasn’t hard to see why French interference was already afoot even before the fall of 1905. South of the Holy Cities lie the administrative Vilayet of Yemen, the domain of the Zaidi Shiites whom have long viewed Ottoman rule as practically illegitimate (albeit for different reasons amongst themselves). By early October, flighty spies from Italy and France were crawling all over Sana’a and the surrounding mountains, pledging on behalf of their governments to recognize Yemeni independence in exchange for rebellion.

On November 7th, the Imam of the Zaidis, Muhammad bin Yahya Hamid ad-Din, declared for revolt.

Attacks on Ottoman troops were already underway till then, but Muhammad’s sanction led the way for a complete uprising in the mountains of Yemen, helped in part by the caches of rifles smuggled from Italian Eritrea and French Obock [1]. For the Ottoman troops stationed there, life quickly devolved into hurried ambushes and wildcat attacks from Zaidi bands, whom arrived with little warning and lightning ferocity before melting away into their rocky surroundings. In quick order, a large region of Yemen found itself completely without any foreign overlordship, with outside support growing as Kostantiniyye’s efforts to contain the situation – namely, holding the valleys and mountains in brutal fashion to sympathising locals – further eroded trust.

Diplomatic schemes were also successful in the Najd, as Italian and French meddling found a deep well of discontent. Over the decades, the Bedouins of the Arabian interior had grown their misgivings over the growing cosmopolitanism of the Ottomans and their increasingly Westernised ways, buttressed by the seemingly twisted ideologies that were spewing out from Cairo, Kostantiniyye, and the Levant. A substantial number of Bedouins have even subscribed to a new Islamic creed as a result, one that has caused ferment and rebellion for the past century: Wahhabism. Led the Saud family and espoused by radical imams, their idea of an Islam purified of any innovation found much resonance among the interior dwellers.

In fact, parts of the Najd was solidly following the Wahhabi branch of Islam by the eve of 1905, and this made it worthwhile for the French spy, Raymond Thibault, to slip into the region to sow discreet separatism and gain military intelligence. He didn’t need to dawdle long; the Wahhabi-aligned Saud family quickly made contact as they sought to use the Great War as a golden opportunity. From their base in Kuwait, Raymond and the intrepid Abdulaziz ibn Saud quickly spun a tight web of fighters, carriers, and informants that revealed the weaknesses of Ottoman troops – though a fair few were put off by a foreigner’s presence in their uprising. As early as late August, raids and ambushes were struck against disparate garrisons while pilgrim caravans from Mesopotamia were shamefully harassed.

A pilgrim caravan crossing the Arabian Desert, photographed in 1904. Despite much protection, many such caravans from Iraq were ransacked, or held for ransom.

But as the months rolled into 1906, the scale of the Wahhabi Revolt became darkly apparent. The Ottomans had defeated previous Saud-Wahhabi rebellions over the past century, but they never sought to supress the puritan ideology itself, seeing it as a time-consuming and wasteful endeavour [2]. This allowed Wahhabism to remain strong amongst the Bedouins and provided a deep well of support and manpower for Raymond and Abdulaziz, whom happily snatched important towns and orchards across the interior. In February, Riyadh was captured and remade into the new centre of the rebellion. In March, southern Iraq saw the beginnings of massive raids.

Despite this, the rise of Zaidi Yemen and the Wahhabi Revolt would be checked, for both rebellions created a backlash from two significant sources.

One of them was the Sharif of Makkah and Madinah, the stewards of Islam’s holiest cities. For decades, the squabbling clans that filled this position had harboured separatist inclinations against distant Kostantiniyye, which had a penchant for intervening in local politics if they turned unpleasant for the Sublime Porte. Since the start of the Great War, many French and Italian contacts urged the Sharif to revolt and to declare himself King of the Arabs and Caliph of Islam, bringing the title home to the land of its birth. However, the revolt of the Zaidis and Wahhabis convinced him of how empty those promises were, and the espousing of Abdulaziz to march on the Holy Cities and destroy “all the vestiges of idolatry placed on Islam”, turned many Sharif-affiliated clans away from the endeavour. If being King and Caliph meant being eaten away by hostile neighbours, then better to side with the enemy that is known. By 1906, the Sharif implored for Ottoman and Egyptian troops to defend the sacred cities against destruction and denounced both the Zaidis and Wahhabis for “planning to destroy the sanctity of the Holy Mosques.”

The Sharif of Makah and Madinah, photographed in Ottoman official dress. circa 1900.

This denunciation found resonance in the second source of the backlash: the appalled reaction of the Arab and Turkish public. Though ethnic nationalism had been curdling in the Ottoman heartland, and although new Islamic movements are afoot in the major cities [2], the absolute majority of the empire’s Arabs and Turks still believed in a unified empire. To them, the Zaidis and the Wahhabis were nothing more than appalling men who are using the instability of the world to sow division at a time when it is most needed. Newspapers from Cairo to Trabzon were filled with calls to defend the Holy Cities and even the Ottoman Sultan Abdulhamid called for, “the internment and immediate confiscation of every French and Italian business for their role in supporting the Arabian fiends.”

And thus, the revolts were halted, but not without terrible cost. Stretched thin over multiple battlefronts, the hastily-cobbled Ottoman and Egyptian battalions found themselves facing wildcat and manoeuvrable bands in the mountains of Yemen and the Najd. Often times, a squadron of soldiers unfamiliar with the terrain would find themselves surrounded by hostile forces without even knowing of it, leading to severe casualties. The intransigence of the local Bedouin and their continued refusal to cooperate further hampered pacification efforts – the reprisal measures against rebellious sympathisers made for a number of burned bridges among the communities. Though the Holy Cities remained in firm control and the vital rail lines of the Hejaz were protected, a large portion of Arabia remained a cauldron of war.

It would be in mid-1906 that events begin to turn in Kostantiniyye’s favour. News of the Zaidis and Wahhabis had spread far and wide across the Islamic world with many being equally appalled by the nature of the revolts and the brazen nature of French and Italian backing for them. British India was particularly affected to send in Indian soldiers to protect Aden, the Red Sea, and the Suez Canal from any hostile takeover. However, the disparity of the Royal Navy’s power in the Indian Ocean vis-à-vis the French and Italian fleets with their Jeune Ecole strategy meant that any Arabian adventure would be unsafe unless every major French and Italian colony in the ocean basin falls into British control.

But by mid-July, the French and Italian presence in the Indian Ocean had whittled down enough for a hastily-made Indian Expeditionary Force to be shipped to Aden and the nearby Horn of Africa. At the same month, a new Ottoman offensive was made to subdue the Zaidis. Faced from a two-pronged offensive and with French Obock and Italian Somaliland now in chaos (Germany declared war sometime earlier), Muhammad bin Yahya finally acquiesced to a ceasefire. A preliminary agreement was made in which the Vilayet of Yemen would be granted some concessions in local religious law, but be otherwise reabsorbed into the Ottoman Empire, much to the disgruntlement of Yemeni locals.

Ottoman troops posing with still-loyal Yemeni irregulars at the end of the Zaidi uprising, circa 1906.

The fight against the Wahhabis would last longer. Though a section of the Indian Expeditionary Force did head for the Persian Gulf to aid Ottoman forces, their initial inexperience in desert warfare created increasingly disturbing casualty counts as Bedouin fighters staged lightning attacks from the desert wastes. However, the Indian forces quickly adapted fast and quickly gained the upper hand as Ottoman supplies steamed in from Mesopotamia. By mid-August, a new stream of replacements arrived from Calcutta as Abdulaziz and Raymond fled from Riyadh against an Indo-Ottoman offensive; as quickly as the Wahhabi revolt arrived, it was quickly slipping away.

It wouldn’t be long afterwards until both men were captured, attempting to flee for Oman.

With that, the Arabian Peninsula returned to relative peace (albeit with underground rumblings). French Obock and Italian Somaliland similarly fell in August with some help from the German colonies, although separatist Somali clans would continue their resistance till the end of the year. By the 15th of December 1906, Kostantiniyye announced that the Red Sea was safe again for pilgrims to travel for the holy cities of Makkah and Madinah…

__________

Notes:

After a whirl of Sarawak and a month of silence, the Great War is finally back! (whoo hoo, 100th page!)

Much of this update is based on the situation in the Arabian Peninsula during the early 20th century. Zaidi Yemen – Northern Yemen to us modern folks – was truly a rebellious region during this time as the locals did not see Ottoman rule as representative of Islam, especially as the Tanzimat replaced much of the old traditional laws with new ones influenced from Europe. From 1904 to 1906, much of Yemen and even the Asir region of south Arabia revolted, and it was only because the Ottomans pledged to halt the use of modern civil law (in the region only) did the fighting came to an end - temporarily.

Likewise, Wahhabism was never fully extinguished in the Najd IOTL. The movement had embedded itself into the local population with local Wahhabi imams and jurists holding strong and keeping the puritanical doctrine alive. For the Ottoman state, it was too costly, time-consuming, and simply gruelling to expunge Wahhabist creeds among such a disparate population to such a local level, though they did realize the danger. This was why the movement bounced back after WWI and the Saud family’s campaigns.

But even with all this, it really should be said that the Arab Revolt of WWI was actually unpopular among the majority of Arabs. Despite popular history (and Lawrence of Arabia), many Arabs of the time saw the Hashemites as basically trying to carve out a realm for themselves. Sharif Husayn’s (the then Steward of the Holy Cities) call for revolt failed to generate any strong response in the Arabic-speaking provinces and many Arabs even saw him as a traitor for dividing the Ottoman Empire! While there was anti-Ottoman sentiment, the majority of Arabs did not want the empire to fall to pieces.

1. See post #1493 for the wartime situation in the Horn of Africa.

2. This is true IOTL. According to The Wahhabi Mission and Saudi Arabia by David Commins, the Wahhabi movement had an entrenched core of support in the Najd due to the Ottomans not prioritizing in de-converting the local Bedouins (see above reasons). Instead, the state prioritized in decapitating the Saud leaders and the major Wahhabist preachers, thinking that was all that was needed to stop the movement.

3. See post #1861 for a look into the new Islamic movements swirling in the Ottoman Empire.

Last edited:

Congratulations! Your dedication to this thread is inspiring and inspirational. It truly has been an honor to have found and read your timeline.After a whirl of Sarawak and a month of silence, the Great War is finally back! (whoo hoo, 100th page!)

Have a Dapper Hornbill

art by Annette Hassell

If the puritanical psychopaths are truly rooted out, then that's a major boon to all of humanity. Since it looks like Germany is not going to be on the losing side in this war, I also cannot see them creating any new abberration, though it does seem likely that Italy will either go communist or create fascism in response to losing this war, with France this time around probably still joined to them by the hip. Will in this timeline there be a second little corporal from Corsica, this one far worse than the first?

🥳May this timeline continue for 100 pages more!

I have to say, that hornbill looks so dapper I have now used it for my icon. Thanks!Congratulations! Your dedication to this thread is inspiring and inspirational. It truly has been an honor to have found and read your timeline.

[snip]

Well, the future is still unwritten on whether the Wahhabist creed could be truly expunged. Village/community imams and jurists aren't always easy to catch, and if pacification efforts continue post-war, there'll be plenty of questions (especially in the cities) as to why the Ottoman state is wasting money and attention on some faraway desert nomads.If the puritanical psychopaths are truly rooted out, then that's a major boon to all of humanity. Since it looks like Germany is not going to be on the losing side in this war, I also cannot see them creating any new abberration, though it does seem likely that Italy will either go communist or create fascism in response to losing this war, with France this time around probably still joined to them by the hip. Will in this timeline there be a second little corporal from Corsica, this one far worse than the first?

As for Europe, the situation is already changing on the political sphere. Leaving aside Germany for the moment, French and Italian politics are greatly in flux as people are realizing that this Great War is lasting uncomfortably longer than imagined. As more and more husbands and sons become casualties, a nascent anti-war movement is brewing amongst some people and political parties, though this is still overshadowed by mainstream war-carrying sentiment. Suffice to say, things will go radical if the fighting keeps on swallowing men and machines.

As for any Great War figures that may grow up to be, er... worse? I have some completely original characters bouncing around, though any historical suggestions are fair game. Whether they are Corsican corporals though, is another matter. 😛

Heads up! Given the length of time now elapsed since the last installment about this (upcoming) region, it might be better to read Post #1492 to refresh what exactly happened. Some of the stuff in the next update are better understood if prior context is also understood.

Why yes, there is a new update coming. 😉

Why yes, there is a new update coming. 😉

Last edited:

Mid-Great War: 1906 - Africa

Adanze Ayeni, When The Elephants Fight: The Great War in Africa (Abayomi; 1997)

…February 1906 saw two important developments for the Great War in Africa. Ironically, one of which saw no war.

In fact, the affair in question was mostly fought in the conference halls of Lisbon. Being the colonial overlord of a large chunk of south-central Africa, the Portuguese Empire was in a unique position during the global eruption. Throughout the Great War’s first year, many attempts were made by many sides to sway the Portuguese government into committing action for – or against – their colonial neighbours, edging heavily with remarks to one particular sore spot: territorial ambitions. While Portuguese Africa was a largely contiguous entity, there existed one weak link dividing the empire’s western and eastern coasts: Mutapa.

Situated on both sides of the Zambezi River, the native kingdom of Mutapa managed to switch allegiances to Great Britain at the last possible minute, which allowed for a British colonial corridor stretching from southern Cape to Nyasaland and Tanganyika [1.]. However, this also cleaved Portuguese Africa into two separate halves, which did not please Lisbon.

Resolving this issue took the better part of the 1900’s, with talks breaking down multiple times on the fracture points of foreign law and white settlement, especially in the British territories. However, the outbreak of global war brought these discussions to a head, and it was perhaps the threat of Portuguese (or British) belligerence that the two sides finally agreed to a compromise. Most of Mutapa would be annexed to Portuguese Mozambique and Central Africa, but a narrow corridor would exist that allowed free movement between British Mashonaland and Nyasaland [2.]. This corridor would be dually-governed by a special administration, consisting of British and Portuguese heads overseeing a condominium government. Thus, Mutapa would be part of both the British and Portuguese Empires.

Naturally, no locals or notables from Mutapa were invited for the February 6th ratification.

The month also saw another, more dangerous development: the completion of the French-laid Trans-Sahara Railroad. Envisioned as a dream project by some of the more ambitious businessmen and colonial expansionists in the Third Republic, the astounding 2,610 kilometre railway was intentioned to bring commerce, transportation, and military control over the interior of French West Africa with a starting terminus at Biskra (in Algeria) to Timbuktu on the Niger River. Such a railway would not only ease transportation of goods and soldiers, but also tie France’s main bulk of her empire together with the metropole.

Construction began in early 1900, but the ballooning of coasts, appalling work conditions, and the realities of building tracks across sand seas quickly slowed the pace of construction. Work further crawled as oil deposits were found whilst rail engineers were drilling for water holes, creating a surge in interest from petroleum corporations and the French government whom now called for works to be redirected. Additionally, spur routes were quickly envisioned to Dakar, Guinea, and the French Ivory Coast, in the hopes of striking valuable mineral deposits. Needless to say, these new plans for the railway, while ensuring interest, vexed engineers.

In fact, the Trans-Sahara railhead was still at the western end of the rocky N'ajjer plateau when the Great War erupted, forcing an abrupt change of plans. With Timbuktu so far away and the belligerent Sokoto Caliphate now a serious threat, the Timbuktu terminus was hastily scrapped for a more direct route to the Niger River, terminating at the riverside village of Bourem. Scores of workers – most of whom were African or Algerian convicts – bled and suffered under the hot sun in the speed-up of construction, pushing the railway ever further south at colossal human expense. On February 26th, the railway reached the outskirts of Bourem, with a linear boneyard over 13,000 workers trailing behind.

An original photograph of a Trans-Sahara Railway locomotive, with a map of the main route across the Sahara Desert. The original route to Timbuktu is shown with the dotted line. Spur routes not shown for simplification purposes.

But despite the eased transport of men, artillery and supplies through the Sahara desert, the colonial troops and their French officers were unexpectedly matched by an unexpected problem: the surprising ingenuity of Sokoto.

In fact, the armies of the caliphate were not only familiar with modern firearms and tactics, but also – and to the horror of the French – brought their own rifles and firearms to battle! Hurried observations confirmed that at least some of their weaponry was traded from the British colonies of the Niger Delta, but most were of an unknown design. In their racialized and pretentious arrogance, the French had been blind to the Sokoto Caliphate’s greatest strength – intimate knowledge of producing gunpowder firearms.

Since its inception in 1804, the Sokoto Caliphate had warred with her Sahelian neighbours and traded with distant nations, bringing in (or capturing) an immense wealth of foreign weaponry. Aware of their potential, the caliphal court quickly began reverse-engineering them and as early as 1820, the workshops of Kano city were producing their first ever muskets and rifles.

By 1905, Kano was widely known as a centre of military manufacturing, with thousands of firearms produced per month to supply the troops of Sokoto’s many emirates [3.]. Local materials such as wood from Lokoja, iron from Bauchi, and nitrates from bird droppings were used to create firearms and powder that established the polity as a semi-gunpowder empire. Rifled infantry formed a noticeable wing in the assembled armies of the caliphate and by 1850, gunpowder weapons became a mainstay in the polity’s many wars, complimenting traditional groups such as archers and spearmen, though it did not replace traditional armaments or tactics.

Unexpectedly, the rise of the British in the Niger delta helped to further develop these rifle-workshops as the former were adamant in not selling newer guns to Sokoto – not wanting to give them a new weapon to use. As such, the caliphate began to innovate in the hopes of matching the British in firepower, even as the polity’s influence waned.

The French had also underestimated the willingness for the British colonies of the Niger south to make common cause with their northern enemy. This was encapsulated with the September 1905 arrival to Sokoto of Oliver Stone, a British senior officer of the West African Rifles. Eccentric and rough, he nevertheless became an important advisor to the caliphate by providing information of new tactics to the royal commanders in battling French forces in the north and northeast. Ironically, caliphal generals also studied previous battles of the British with their neighbours over the decades in order to match their technologically capable counterparts.

Examples of locally-produced rifles and muskets used by the emiral armies of Sokoto, pre-Great War.

Against heavy opposition, Oliver Stone also brought several Enfield rifles with him to Sokoto in the hopes of mass-producing them from the Kano workshops. With the Great War, the city’s smiths and craftsmen gained an indispensable role in supplying guns, cannons, and field weapons to the caliphate’s borders. Though they were unable to truly replicate the exact capabilities of the Enfield rifle, their copycats were just good enough for Sokoto to hold back French advances at the Niger borderlands. As the local economy became devoted to war production, firearms manufacturing grew to such a rapid pace that even several British proposals were made to contract Sokoto for guns and armaments, especially for the Dahomey occupation and the Borgu campaign.

Perhaps, the only global comparison to such a proliferation of native-led weapons production – in a world war, at that – could be the hill peoples of Indochina [4.], whom created their own rifles, muskets, cannons, and gunpowder from their mountainous rainforests.

Still, the regional situation by May 1906 did not favour the British and their allies. Despite increasingly desperate supply runs by the British, the Trans-Sahara railway provided French forces with near-enough materials to even the scales against the isolated British colonies of West Africa. A heavy March offensive nearly took the last remnants of the British Gold Coast, which only stood firm due to emergency supply runs from Royal Navy convoys. Sierra Leone fared little better with many British forces beginning to operate in the far-flung backwoods of neutral Liberia.

Meanwhile, a successful war against French Dahomey quickly stalled as angry locals fiercely rose up against their new colonial occupiers, whilst the petty states of the Borgu Confederacy to the north devolved into civil war as traditional rulers fought the forces of France, Britain, Sokoto, and each other in succession…

********************

Wolfgang Holtzmann, A History of War in German Africa (Osprey; 1994)

…Then Germany declared war.

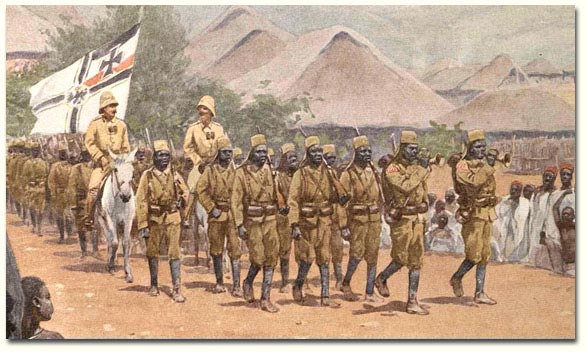

The introduction of the German Empire upended everything about the Great War in Africa. German colonies neighboured French, British, and Italian ones in East and West Africa, staffed with local troops that have seen active service in tough conflicts, such as the schutztruppe of German Equatorial Sudan against the fearsome Dervish Caliphate. Now, they are thrusted into taking over their new enemies’ colonies.

Togoland saw the first conflict, with two battalions of Tirailleurs and Zouaves attempting to swallow the territory from an amphibious operation. If it were not for the presence of British-occupied Dahomey next door, they could have succeeded, but the fight for Togoland became a morass of ambushes and unplanned attacks, with the rebellious locals of Dahomey adding to the fire by slipping into the territory. It wasn’t until the arrival of the Kreigsmarine later in June that Togoland returned to order, though not without some heavy casualties from all sides.

Kamerun was next, with French colonial troops attempting to bombard the coastal capital of Douala in late May. However, the presence of several German gunboats helped to thwart the attack and parry off seaborne assaults until mid-June, when Germany fully entered the Great War as part of the Four Powers; from then on, the territory became the staging ground for the western half of the Central Africa theatre. However, the heavily forested southern border made any colonial wars there near-impossible, prompting the schutztruppe to push westwards into occupying French Oubangui-Chari and defend the Ottoman-aligned sultanate of Ouaddai. An attempt was made to strike southeast towards the Oubangui River in hopes of boating down the watercourse, thereby attacking French Congo and Gabon ‘from behind’. But this was already expected, and French reinforcements quickly turned this campaign into another morass by mid-July.

But the Germans did have one surprising pillar of support in West Africa: the Sokoto Caliphate. Upon realizing that they shared similar enemies, the caliphate’s infantry and cavalry regiments quickly became involved in the Oubangui-Chari theatre as well. Of special note was the Adamawa emirate, which had seen more than half its territory taken by Germany in 1904 and added to Kamerun [5.], and yet now faced a similar French enemy. The Adamawa emir was hesitant to offer aid to a Power that had humiliated and partitioned the land, but the French incursions through the Lake Chad basin were too serious to ignore, as was the threats made by the Sokoto caliph for not cooperating. Eventually, he acquiesced and allowed the caliphal armies to march through into Kamerunian territory, helping German officers to defend Lake Chad and the state of Kanem-Bornu from French incursions, along with providing support in the central Sahel...

…For the French in Ouaddai, the arrival of these two forces were initially met with disbelief, for it was assumed both Sokoto and the Germans would fight each other over territorial claims. But as weeks passed, it became clear that the opposite had occurred, and disbelief turned to irritation. They were so close, so close, to completely bringing Kanem-Bornu and Ouaddai to heel! Their forces had taken both the sultanates’ capitals and even some of their princes, with their fathers on the run. Now, they were facing two combined enemies which aimed to liberate the states.

Initially, resistance to the schutztruppe and Sokoto armies was easy. But the former forces then managed to cut-off French supply routes to the Oubangui River, stranding the Sahelian forces in a sea of enemies. Sokoto imams subsequently made contact with the Senussi order of Ouaddai, transferring enough food and firearms to enable its escaped ruler, kolak Muhammad Salih, to return to his homeland at the head of an avenging army. With an untenable situation, colonial troops retreated from Kanem-Bornu in late October with three different forces closing in. Finally, at the Ouaddaian capital of Abéché, 6,001 French colonial troops made an ignominious surrender – the first in the theatre.

Rare photograph of kolak Muhammad Salih, the ruler of Ouaddai, at the head of a victory parade at Am Timan.

In East Africa, the local forces faced a different brew of enemies. Till then, the main concern for the colonial administration was the Dervish Caliphate of Kordofan, still frightfully strong although on the wane. Now, orders were given to march into Italian Somaliland and reach the Red Sea coast, relieving the Ottoman-allied sultanate of Majerteen and reinstate British Somaliland. Fortunately, the schutztruppe of the east were better trained and battle-hardened, repelling Dervish attacks throughout the years before the Great War.

Because of that, the Somaliland thrust of early June became such an unexpected success to local command that by the following month, almost the entire Italian colony was occupied – much to the confusion of Italian officials whom saw their Askaris steamrolled by regiments from Equatorial Sudan. However, it should also be noted that several Somali clans did continue an insurgency against foreign rule for the rest of the year, seeing the advancing Germans as inhibiting their freedom. Nevertheless, the sultanaate of Majerteen was relieved in early July with British Somaliland reinstated by the end of that month – albeit under German protection.

It was also during this time that several warships of the Kriegsmarine managed to sneak past the maelstrom of southern Africa (and her choppy seas) and French Madagascar to safeguard the Horn of Africa. Together with remnants of the Ottoman and British navies and an expeditionary force cobbled from India [6], both French Obock and Italian Eritrea fell across the month of August, opening the Red Sea to free travel once more. In a span of several months, the Horn of Africa was neutralized as a theatre of the Great War.

This endeavour did create one unfortunate side-effect, as the Dervish Caliphate began re-expanding south along the Nile and west into Darfur (yet another Ottoman ally) as schutztruppe battalions were relocated for the Red Sea theatre. But this phase of expansion would be the state’s last, as Darfur quickly hashed-out an agreement on accepting German aid in exchange for abolishing the slave trade – Ouaddai and Kanem-Bornu did the same a month earlier. As the months passed into the winter dry season, Dervish-conquered lands were slowly retaken, and the Dervishes would find themselves retreating more and more…

********************

Adanze Ayeni, When The Elephants Fight: The Great War in Africa (Abayomi; 1997)

…the one place where German aid did not help much was in southern Africa, which saw a failed British expeditionary attempt to take French Madagascar [7]. The island – and the surrounding Comoros archipelago – formed a stronghold against the colonies of the Cape and formed a massive thorn to their economy as cargo vessels became subject to commerce raids, halting the local meat and diamond-focused export industry.

By October, another white-led expedition was cobbled-up from the Cape and Natal governments, this time with improved weaponry brought from German supply runs. Initially, this second expedition seemed to be more successful than the first, particularly as British and German gunboats managed to ward off enemy ships to stage a landing on the western part of the island, near Morondava. However, their luck soon started to run dry as the Cape and Natalian forces, whom were all either White or Afrikaner, became surrounded by hostile Malagasy locals.

In a brilliant act of deception, the Governor-General of Madagascar, Patrice Durand – who was appointed to the colony just before the Great War began – managed to convince the Malagasy notables to antagonize any and all British forces and instead support the French Third Republic. Durand claimed how the Cape and Natal’s race-discriminatory policies would be imposed on local society while the French would guarantee equal rights to all Malagasy. Given local attitudes of whites to the Indian and African labour of the plantations and diamond mines of the region, the arguments were not without basis, which further made local notables more wary of any foreign incursions.

As a result, the expeditionary force found itself trapped in the Madagascan interior by August as local forces cut off supply routes to the sea and picked off local companies one by one. On August 12, the half-starving and diseased force surrendered to the Governor-General, marking another setback to Cape Town and Durban.

With the debacle hanging over many heads and the cyclone hanging season arriving in months, a third expedition was ruled out. However, it was during this time that a new suggestion came to the regional Royal Navy squadron: whittle down Madagascar’s naval protection piece by piece, and harangue enemy gunboats so that they run out of fuel. And with the political impact of White and Afrikaner casualties making unsavoury waves, another proposal was hashed out in which Black, Coloured, or Indian forces would go to war instead…

____________________

Notes:

I have to confess, this update to a long while to write and edit. Given the length and breadth of the Great War in Africa, I know I can’t fill in every detail of every conflict (do you notice the absence of a certain controversial rubber-producing colony?). Maybe because of that, I have some mixed feelings on this instalment as the writing and style is not exactly how I envisioned it to be. I’m pretty sure I missed out a few important OTL details!

But in the end, it’s better for things to be finished rather than be perfect.

1. The capture of Mutapa and Nyasaland into the British orbit referenced as far back as Post #1067.

2. In effect, this arrangement reconciles the Africa map in Post #1492 with the world map in Post #1754. The British would prefer the stylized map with the whole of Mutapa included, but the basic shape of the corridor was already being drawn by the end of 1905. The reason it took until February to ratify was that the Portuguese wanted more guarantees of dual government, and the British wanted more guarantees of easy travel. Details, details…

3. Lest you think I am joking, the British themselves were surprised at how Sokoto locally-produced actual firearms IOTL. In the book Warfare in the Sokoto Caliphate: Historical and Sociological Perspectives by Joseph P. Smaldone, Sokoto even brought field guns (some locally-made, some foreign-bought) to battle the British with the latter taking surprisingly heavy casualties for a better-equipped colonial army with maxim guns.

4. Do you all remember the Hmong people of Laos in Post #1790? Whom also made their own firearms? I hope you do…

5. To see how Adamawa lost almost all her territory to German Kamerun, see Post #1090.

6.Previous update reference!

7.Refer back to Post #1492 on how that debacle took place.

2. In effect, this arrangement reconciles the Africa map in Post #1492 with the world map in Post #1754. The British would prefer the stylized map with the whole of Mutapa included, but the basic shape of the corridor was already being drawn by the end of 1905. The reason it took until February to ratify was that the Portuguese wanted more guarantees of dual government, and the British wanted more guarantees of easy travel. Details, details…

3. Lest you think I am joking, the British themselves were surprised at how Sokoto locally-produced actual firearms IOTL. In the book Warfare in the Sokoto Caliphate: Historical and Sociological Perspectives by Joseph P. Smaldone, Sokoto even brought field guns (some locally-made, some foreign-bought) to battle the British with the latter taking surprisingly heavy casualties for a better-equipped colonial army with maxim guns.

4. Do you all remember the Hmong people of Laos in Post #1790? Whom also made their own firearms? I hope you do…

5. To see how Adamawa lost almost all her territory to German Kamerun, see Post #1090.

6.Previous update reference!

7.Refer back to Post #1492 on how that debacle took place.

Last edited:

I had no idea that Sokoto was that good at making guns

Most of them are probably artisanal, a step up from jezails but enough to fight off lightly equipped French desert expeditions.

I wonder how much the German alliance has improved Sokoto's hardware - do the Germans value them enough to equip them with surplus artillery and Maxims?

The guns of Sokoto are a nice touch, but I enjoy the emphasis on politics and logistics. Really shows how the Europeans, for all their hard power, were operating half-blind.

I had no idea that Sokoto was that good at making guns

This, mostly. Sokoto traded with the British over the 19th century for modern weaponry, but they also reverse-engineered musketry and rifle-making over the decades, with echoes of this found even in Nigeria today (some of the locals and terror groups can make guns out of nothing but scrap). Production was artisnal, with the smiths and craftsmen of Kano making them in-between other, more local products. Quality-wise, they are not good for accuracy as European firearms, but they did have a place during the seasonal war campaigns of the caliphate; there was always a group of 100 or so riflemen on any local campaign, and the local forts are always in need of guns for fending off outside enemies. Or French incursions.Most of them are probably artisanal, a step up from jezails but enough to fight off lightly equipped French desert expeditions.

I wonder how much the German alliance has improved Sokoto's hardware - do the Germans value them enough to equip them with surplus artillery and Maxims?

The Germans are also shocked and a bit impressed by this, and have given Sokoto forces a few spare guns and artillery in the hopes that they can use them well (or produce them. Knock-offs might still be useful when you're hundreds of miles from any weapons cache). Still, there are some powerful weapons - such as the Maxim gun - that they don't give to the caliphate, out of baseless fear than anything. It's one thing to produce knock-off rifles, but what if they can make knock-off machine guns? 😨

The modern idea that Europe knew what it was doing in Africa papers over the fact that, half the time, they kinda don't even know what they were doing. When you are trying to claim a place without any automobiles, railroads, telegraphs, or even horses, let alone wage war and diplomacy there, half-blindness and guesswork is the best you can get.The guns of Sokoto are a nice touch, but I enjoy the emphasis on politics and logistics. Really shows how the Europeans, for all their hard power, were operating half-blind.

Last edited:

Taste is an odd thing, as we all know. One man's meat is another man's poison.

When I first got into alternate history, the two timelines that seemed to be written over and over again were Confederate wanks and German victories in alternate world wars.

Endless writing about the triumph of the Kaiser is not, of course, distasteful in the sense that Nazi or Confederate timelines often are. True, the genocidal imperialism of the Kaiserreich tended to get brushed over, but especially in the 2000s that was common for writing about any western power.

The main thing was that it was boring. I made some comment a few weeks back that it seemed like the slightest change to pre-1914 Germany would result in the swift capture of Paris. I could add that what followed was always a fascist/quasi-stalinist France. Britain usually allied with Germany in these scenarios, since people who loved the Kaiser's army tended to love the Royal Navy even more. It was all so thoroughly predictable. I'm not a particular francophile- true, I speak more French than I do German, but it's very much at the level of 'Anglo shows the waiter that he's making an effort so they take pity and speak in English.' After a while, though, I ended up finding myself treasuring any timeline where the Third Republic won out over her foes, on the slightly irrational basis that this would irritate the writers I like least on the site. There are, of course, honorable exceptions: I love EdT's Boulangerist France in Fight and Be Right and Jonathan Edelstein's strange Second Empire in the Great War- but generally speaking I feel like once I see the French lose the Great War I can more or less predict what's happening next.

As I said, taste is an odd thing.

That long lead up is to put the following into context: to my deep irritation, @Al-numbers, you have written a Great War that goes against every one of my expressed tastes and I am loving it. I love the portrayal of the Empires, I love the centering of the Africans and Asians within their own stories, I love the way you take classic tropes of the period and put your own spin on them.

How dare you make me like a timeline where the Germans and British are beating the Third Republic? How bloody dare you?

I mean, I prefer to think that I'm rooting for Sokoto rather than the Kaiser, but even still!

When I first got into alternate history, the two timelines that seemed to be written over and over again were Confederate wanks and German victories in alternate world wars.

Endless writing about the triumph of the Kaiser is not, of course, distasteful in the sense that Nazi or Confederate timelines often are. True, the genocidal imperialism of the Kaiserreich tended to get brushed over, but especially in the 2000s that was common for writing about any western power.

The main thing was that it was boring. I made some comment a few weeks back that it seemed like the slightest change to pre-1914 Germany would result in the swift capture of Paris. I could add that what followed was always a fascist/quasi-stalinist France. Britain usually allied with Germany in these scenarios, since people who loved the Kaiser's army tended to love the Royal Navy even more. It was all so thoroughly predictable. I'm not a particular francophile- true, I speak more French than I do German, but it's very much at the level of 'Anglo shows the waiter that he's making an effort so they take pity and speak in English.' After a while, though, I ended up finding myself treasuring any timeline where the Third Republic won out over her foes, on the slightly irrational basis that this would irritate the writers I like least on the site. There are, of course, honorable exceptions: I love EdT's Boulangerist France in Fight and Be Right and Jonathan Edelstein's strange Second Empire in the Great War- but generally speaking I feel like once I see the French lose the Great War I can more or less predict what's happening next.

As I said, taste is an odd thing.

That long lead up is to put the following into context: to my deep irritation, @Al-numbers, you have written a Great War that goes against every one of my expressed tastes and I am loving it. I love the portrayal of the Empires, I love the centering of the Africans and Asians within their own stories, I love the way you take classic tropes of the period and put your own spin on them.

How dare you make me like a timeline where the Germans and British are beating the Third Republic? How bloody dare you?

I mean, I prefer to think that I'm rooting for Sokoto rather than the Kaiser, but even still!

I really appreciate your efforts to combat bygone cliches, but also, (as al-numbers can testify), I have expressed this sentiment to him as well.How dare you make me like a timeline where the Germans and British are beating the Third Republic? How bloody dare you?

All of that.

Just... all of that.

Hahaha! I am delighted and honored to have turned your tastes for this timelime!

Confession time: This timeline was partly the result of a "what-if" fantasy scenario from when Male Rising was still around, but it was also a rebuttal to the usual standard fare of "mainstream" Alternate History discussion. This may be the, "old foreign 2013 AH guy" within me speaking, but I often find myself rather bored of the usual Roman, Byzantine, Norse, European, American, or western fare that often fill this subsection of AH.com. And as a foreigner living halfway from the Western hemisphere, I feel disconnected with the many many many Confederate timelines, questions, and what-ifs that seem to pop-up without end. It feels like being in an American-themed social party as a Malay fisherman. The fact that a lot of timelines often have a bent towards large-scale war is another bore; I think I have noted multiple times before that I abhor writing about conflict and especially industrial conflict.

Maybe because of that, I try to present a different side to war that most people don't, or refuse, to see. Foreign battlefronts, indigenous ingenuity, Asian and African perspectives, the rise of hysteria and what it can do to vulnerable minorities, people and leaders caught in situations they never expected... it feels a lot more expansive, deep, and nuanced than the usual "Empire A fights Empire B in an offensive at 6:31 am using Krupp artillery by General X". There's nothing wrong with such a timeline, but I find it somewhat lacking and not to my taste.

And I think some of the more brilliant timelines on here like Male Rising, With the Crescent Above Us, Minarets of Atlantis, A House of Lamps, and such... have influenced me to take more attention towards people, and how they lie and react behind/towards every event and movement. I mean, I might be the only person in the world who writes Kaiser Wilhelm II getting deeply unsettled by homophobic hysteria that is consuming the army and his family and friends! Who wouldn't if they were faced with something like that? The effects of that hysteria influenced events both far and near, and the ripples are still making events this far into the world. People are so much more than the stories and events that often frame them, and how they live in a world like this - is, in my opinion, far more worth writing about.

I guess the point of this rambling of mine is: yeah, I feel ya. Cliches be in the dustbin. And thanks.

(And if it makes you any better... You can root for Sokoto. Germany did take part of its territory before the Great War. Who's to say their friendship will stay a friendship after this all blows over?)

Also: Nobody in the Great War will go through the expected "mainstream AH" tropes. Britain will face a rocky empire, France and Italy will not go quietly into alternate Fascism/Communism (even if they win or lose - seriously, only those ideologies?), Austria-Hungary will not go through what most people would think off when they think "collapsing empire", the Ottomans will find winning to be a double-edged sword, and Germany will find that wanting hegemony is faaaaar different from actually keeping/maintaining/preserving hegemony. And this is to say nothing of places abroad like China, Sarawak, or Benin (oh god, I need to rectify that being absent in the update!).

I really appreciate your efforts to combat bygone cliches, but also, (as al-numbers can testify), I have expressed this sentiment to him as well.

In more private and informal settings too!

And lastly, I think you will all notice that the title has changed a little bit. Given the length of time this TL is up, I think there are a fair number of new AH.com people who have no idea what Rajahs and Hornbills even mean!

@Al-numbers - I have to say, I agree with you fully. For me, TLs like this and the ones you mention are the best things going on AH.com, because they look at areas of history less travelled and because of the attention to the individual

@Al-numbers After reading your response, I felt I had to reply and add my own feelings.

While taking courses in undergrad, one of the most formative courses that I took was a course that covered how to write history papers, which also doubled as a state mandated class covering the history of the state I was going to college in. One of the books that we covered was The Middle Ground by Richard White, and what fascinated me about the book and what was shown to me was just how much people attempted to make their own way at the edges of imperial power, how oppressed peoples would do what they could to make room for themselves for as long as possible. Essentially, it showed the human agency at the edges of the forces of empire and history, and it fascinated me so much.

Some many story lines are very much "Forces of History" focused, and I enjoy a *lot* of those stories. But this story shows such a human side, shows the agency of many non-western groups, rather than them just being swept up in history, and causes this timeline to come alive in a way few others have. You have an amazing touch, and I am very happy I have gotten to read it.

While taking courses in undergrad, one of the most formative courses that I took was a course that covered how to write history papers, which also doubled as a state mandated class covering the history of the state I was going to college in. One of the books that we covered was The Middle Ground by Richard White, and what fascinated me about the book and what was shown to me was just how much people attempted to make their own way at the edges of imperial power, how oppressed peoples would do what they could to make room for themselves for as long as possible. Essentially, it showed the human agency at the edges of the forces of empire and history, and it fascinated me so much.

Some many story lines are very much "Forces of History" focused, and I enjoy a *lot* of those stories. But this story shows such a human side, shows the agency of many non-western groups, rather than them just being swept up in history, and causes this timeline to come alive in a way few others have. You have an amazing touch, and I am very happy I have gotten to read it.

Threadmarks

View all 145 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Perkahwinan of the Rajah: mini-afterword Mid-Great War: 1906 - Arabian Peninsula Mid-Great War: 1906 - Africa Mid-Great War: 1906 - Oceania 1906 summary: part 1 / 2 1906 summary: part 2 / 2 Interlude: An Eclipse of Change (1907) Late-Great War: 1906-1907 - East Asia and the Russian Far East

Share: