You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Of Rajahs and Hornbills: A timeline of Brooke Sarawak

- Thread starter Al-numbers

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 145 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Perkahwinan of the Rajah: mini-afterword Mid-Great War: 1906 - Arabian Peninsula Mid-Great War: 1906 - Africa Mid-Great War: 1906 - Oceania 1906 summary: part 1 / 2 1906 summary: part 2 / 2 Interlude: An Eclipse of Change (1907) Late-Great War: 1906-1907 - East Asia and the Russian Far EastTunisia has more holes than a pretzel

Port cities, port cities everywhere!

It might as well be landlocked now...

Would love to see that upper crest with the fish and lion replaced with a Hornbill and Leopard Cat, and of course the house words.

While the I like the idea behind the composition a lot, and the fact that it only uses four colours, the badgers and the hornbill wings blend into each other rather badly. Perhaps move the supporters further apart, so that their paws no longer cover the shield and shrink them just a little. Then shrink the hornbill such that there's a gap between the wings and the badgers' heads?

I personally always wanted to see an Orangatang and Bornian Elephant on the heraldry maybe holding the emblemWhile the I like the idea behind the composition a lot, and the fact that it only uses four colours, the badgers and the hornbill wings blend into each other rather badly. Perhaps move the supporters further apart, so that their paws no longer cover the shield and shrink them just a little. Then shrink the hornbill such that there's a gap between the wings and the badgers' heads?

Found it, theres a link to the original reddit post@LuckyLuciano Thanks for sharing! Did you find that or make it?

So does anyone think there will be one camp emerging the victor in the Great War in Europe, or will the various sides see vastly different results for their members?

While the I like the idea behind the composition a lot, and the fact that it only uses four colours, the badgers and the hornbill wings blend into each other rather badly. Perhaps move the supporters further apart, so that their paws no longer cover the shield and shrink them just a little. Then shrink the hornbill such that there's a gap between the wings and the badgers' heads?

I personally always wanted to see an Orangatang and Bornian Elephant on the heraldry maybe holding the emblem

Toying with emblems is an idea I've had since starting this timeline, but I am always confused on whether the Brookes would commission a separate state heraldry for the kingdom to differentiate the polity from their personal family crest. Admittedly, I'm basing this on modern Malaysia's system of national, state, and (royal) family heraldry, so there is some bias, and having separate crests would preserve the badger as a personal reminder of the family's British heritage, despite it being an anomaly for the tropical country.

For a Sarawak coat-of-arms, the Rhinoceros Hornbill would undoubtedly take center stage, as it is a prominent animal in general and a powerful symbol of strength and war. The star would either be discarded or changed to better reflect the regions of the kingdom (Sarawak, Sabah, and the Natuna/Anambas archipelago) and I would personally place it above the hornbill, like Australia's coat of arms. The shield is a wildcard though, since this Sarawak holds part of the OTL Riau islands and is going to incorporate the region of Sabah, so the central crown might be surrounded by a different plethora of regional designs ITTL (and if Sentarum joins, that's going to change further).

The animal supporters are the most contentious of all, and I can see heraldry makers commissioned by the government ITTL also splitting hairs over the issue, as there are a lot of beasts that can qualify, each signifying noble traits and symbolizing parts of the kingdom. Orangutans (Sarawak) and Proboscis Monkeys (Sabah) are obvious candidates, and they are also featured in several Dayak tales as wise beings. But there is also the Bornean Elephant, the Clouded Leopard, or even the Bornean Tiger which is still remembered in oral tales despite it being extinct since the holocene era.

The scroll looks alright, though I'd personally prefer the color to be white or light blue to counterbalance all the yellow, though that does bring into conflict with Malay symbolisms of gold being a color of royalty.

So does anyone think there will be one camp emerging the victor in the Great War in Europe, or will the various sides see vastly different results for their members?

To put it in a nutshell (and in risking spoilers), almost none of the combatants would get what they want.

July-December 1905: Africa and Oceania

Adanze Ayeni, When The Elephants Fight: The Great War in Africa (Abayomi; 1997)

While the campaigns of Sundaland and the Pacific Ocean turned many public heads in Europe and the Americas, it was Africa that truly formed much of our modern view of the Great War in the colonies. Far from the depressive and hellish tribulations of Europe, the African theatre was a campaign of empires under the blazing sun and savannah, fought across exotic jungles and waterways of imaginative (and exaggerated) nature. Instead of the drudgery and cynicism of political leadership back home, the African front – or rather, fronts – were accompanied with extraordinary tales of native kingdoms fighting for a side, or even for a right to just exist. While this view is somewhat accurate to an extent, it also glosses over the complexity of the ground situations that were faced by the combatants themselves…

…The first colony to fall weren’t those of North Africa or near the Ethiopian borderlands, but a tiny sliver of British-ruled territory surrounded by a voluminous chunk of French West Africa: the Gambia Colony. Comprised of nothing more but the banks of the Gambia River, the local garrison lasted less than 72 hours after the British declaration of war. Sierra Leone was next, but the invading Armée Coloniale found the colony a tougher nut to crack as British authorities began smuggling goods and supplies from the neighbouring (and neutral) state of Liberia, helping Freetown to withstand its long siege. The Royal Navy’s prioritisation of West Africa also lent support in the form of armed convoys battling the French navy to relieve Sierra Leone and the Gold Coast, which also suffered from a besieged capital and an unruly hinterland.

The Horn of Africa also witnessed some early skirmishes for the French-led colonial force as British Somaliland came under attack from both its French and Italian namesakes. While the territory fell just as quickly, the presence of both the British and Ottoman navies on Suez and the Red Sea meant that the Somaliland coast was never fully pacified, and the nearby colonies of Aden and Oman halted any notion of a complete Franco-Italian sea. In fact, an attempted naval takeover of Perim and the Majerteen Sultanate in mid-August was repulsed barely a week later by a combined Anglo-Ottoman force with (distant) Indian support, securing the strategic capital of Alula and the naval bases there.

In short, what promised to be a quick colonial war devolved into tit-for-tat attacks from the Suez Canal to the Gulf of Aden which lasted for a large portion of 1905. Stymied on land and sea, both sides began to play-off the local Somali and Yemeni clans to fight one another or to switch sides, dangling the prospect of advancement and better treatment for their peoples once they’ve won...

…North Africa, given its proximity to Europe proper, received some of the more notable fighting. Ottoman Tunisia was particularly favoured by both France and Italy, with the latter having long-shelved plans for the region for the past two decades [1]. Hoping to pre-empt the inevitable, orders were quickly given from Kostantiniyye for Tunisia’s troops to invade the local French and Italian-held seaports. Instead, this only brought the wrath of the two nations on the African Vilayets; Tunis quickly fell to a combined Franco-Italian assault while divisions of askaris, tirailleurs, and the French Foreign Legion plowed through the Vilayet of Tripolitania. Further west, the war breathed fresh attention to the ongoing Trans-Sahara railroad project as engineers raced to complete a now-strategic military route from Algiers to Timbuktu. Protecting this endeavour were companies of Méharistes (French camel cavalry), whom streamed out into the vast wastelands of Ottoman Fezzan, aiming for Egypt and to link up with another colonial division that moved northwards from the French Congo.

Image of a French company receiving the surrender of a Bornu troop commander (left) and french soliders disembarking near British Gambia (right), circa 1905.

But here, too, rose resistance. The central and eastern Sahara have long been a bulwark of the Senussi order, a Sufi fraternity that controlled the mountains and oases of the vast expanse. The religious brotherhood have long been held in contempt by the Ottomans and their doctrines are considered somewhat wayward, but the advance of French forces did a lot to bridge the divide. The Algerian camel cavalries found itself attacked by Senussi and Toubou guerrillas as they reached the Tibesti Mountains, leading to costly operations of taking disparate oases and defending them against outside attacks, all in the midst of avoiding hit-and-run raids accentuated by the harsh and craggy terrain.

Similarly, the Sahelian states of Ouaddai and Kanem-Bornu saw the advancing French as a sure sign of peril and threw themselves into the fight, if not for the Ottomans than for themselves and the entrenched Senussi fraternity. The ruler of Ouaddai, kolak Muhammad Salih, was a prominent Senussi member himself and rallied his state to fight the new threat that would surely trample the Sahel, diverting resources and weaponry that was previously used against the Dervishes (mostly in the form of incursions). But while the Saharan frontier was manageable, the French forces coming from the Congo were much better armed and prepared, and though both states managed to slow the advance considerably, they couldn’t stop it. By December, parts of Bornu and southern Ouaddai had fallen and both states seemed to be on the edge of collapse…

…Many have noted how the Royal Navy could have turned the tables earlier if it weren’t for Madagascar, and they were correct. The island formed a solid base for French forces in the Indian Ocean and checked the Royal Navy from going past the Cape Colony, as well as allowing the French to use Jeune Ecole tactics to harass British Zanzibar. From shipping raids to surprise attacks, the British navy found itself massively overstretched across the African east coast as it tried to protect the commerce routes stretching to and from India and the Red Sea. Given the exporting nature of the Cape Colony and her neighbours, these actions provoked nothing less than outrage and alarum as the local economy floundered, and it wasn’t long before an expeditionary force was quickly hashed out from Cape Town.

However, the settler-comprised September Expedition would become an unambiguous catastrophe. Surrounded by French cutters and hampered by undersea banks, the attempted landing at Toliara become a bloodbath with over 7,000 South Africans dead and nearly 5,000 wounded before the force staged an ignominious retreat. So profound was the defeat that it would effectively kick-start the region’s political maturation, yet before the Cape Colony and her neighbours could cobble another white-led force, the cyclone season struck. Stretching from October to April, the choppy seas and rough weather forced both sides to hunker down and lull the fighting as a default, yet many knew that the bloodshed will resume once the southern summer ends…

********************

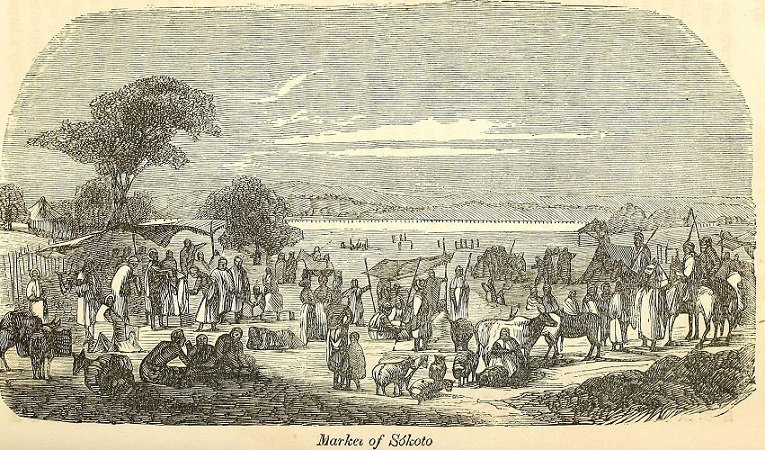

Muhammad Yahaya bin Mahmud, Sokoto: Our History, (MPH Asa: 2016)

…Of all the conflict theatres, the Sokoto Caliphate formed the most surprising battlefront of 1905. Already under pressure from European ambitions, the empire’s emirates were alarmed by the onset of world war which would undoubtedly turn the caliphate into a massive stomping ground by their British and French neighbours, regardless of local protests. But being more numerous and populated than the Sahelian states, and possessing invaluable manpower that could be trained and directed, the French and British decided on a more devious tactic for Sokoto: getting the caliphate’s emirates to fight for them.

And indeed, the summer of 1905 was filled with foreign emissaries shunting to and from the capital and the surrounding polities, imploring them to fight for their side and offering sweet incentives for involvement. Both France and Britain offered acknowledgment of the caliphate’s independence, as well as preferential trade deals and an infusion of cash to facilitate internal development. Sokotan laws shall be upheld and there were even proposals to relax certain measures on anti-slavery, which had become a sore spot for the empire. Unsurprisingly, Sokoto’s many emirates bickered long and hard over the merits of involving themselves over the matter, with several even undergoing localised civil wars as prospective heirs fought for a right to involve themselves in the diplomatic squabble.

It was one such local conflict that finally tipped the pot. The emirate of Gwandu had always maintained an arm’s length of distance with the main metropole, with its emirs possessing a rather independent streak and being suzerain of several (smaller) emirates of its own. However, the preceding decade was unkind to Gwandu as French forces began peeling off polity after polity from under the state’s oversight. Now, France is offering to return them back and give a recognition of independence if Gwandu turns against Sokoto and fight the British down south. Highly controversial, the offer would lead the state to a month of turmoil as the emir’s family fought for their say, with a pro-French prince finally winning in mid-September.

This turnabout shocked Sokoto. That one of her emirates could break off is one thing, but to turn traitor and side with a colonial power to stomp on the caliphate? That was outrageous. It was this that precipitated the British intervention that halted a Franco-Gwandu force outside Sokoto’s very capital, leading to sultan Muhammadu Attahiru plunging the empire to war on the British side. Still, the following months saw massive casualties on its part as the caliphate’s emirates struggled to defend its borders against the Armée coloniale, with probing attacks from the north and west costing precious armaments and thousands of lives. Despite being a military recipient of the Ottomans, the empire’s modern weapons were in desperate supply and whatever that was given from the British south was barely enough to maintain defensive positions.

But as the Royal Navy braved the dangerous Atlantic to offer fresh aid, and as British forces cut through French Dahomey to prevent a new front from arising against Lagos, and with Beninese runners carrying food and weapons up the Niger in record time, the caliphate held its ground. And in December, the first victory was tasted as Anglo-Sokotan forces stormed the northern French-toppled town of Zinder, which would be later added as the caliphate’s newest emirate…

********************

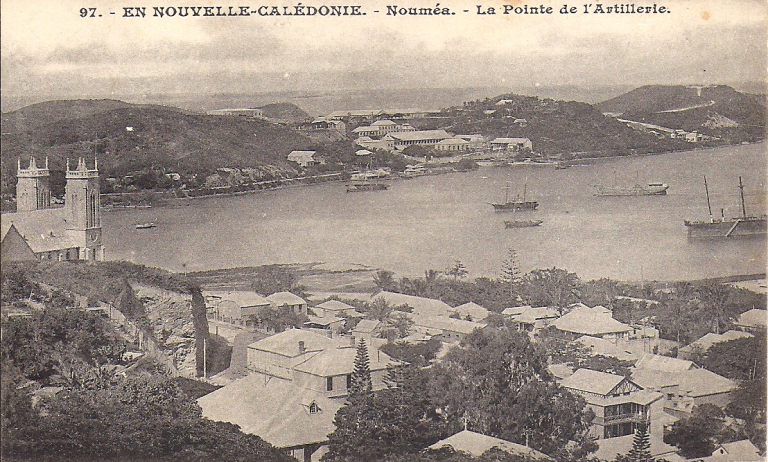

Petru Nuñez, A History of Pacific Wars; The Great War, SW Cornellia: 1989)

…When news of the war declarations reached New Caledonia, it was met with shock and bafflement. Compared with the rising tensions over at Sundaland, life in the Pacific showed little of heightened tensions, save for the clunky and ever-quarrelsome neighbours that were Australia and… whatever was the New Hebrides. But even then, there was nothing that could ever merit a full-blown war.

And for weeks afterwards, it seemed the island would remain at peace. But that all changed with the arrival of the French and Italian gunships in early August. While the bulk of the belligerent navies roamed in the Atlantic, Mediterranean, and Sundaland theatres, a few managed to steam through to engage the British colonies in the vast southern ocean. Operating from Noumea, they would scour the surrounding straits and seas for British shipping, requisitioning their cargo before commandeering the vessels from the interned crews. The New Hebrides became a particular target, with the island chain quickly falling in a matter of days. In a twist, much of the British planter class was comparatively left alone, albeit after they swore allegiance to the new French administration – the threat of property confiscation was good enough an incentive to toe the new line.

This set the tone for much of the Great War’s Pacific theatre: speedy gunships raiding commercial vessels while claiming atolls and islands for the major alliances stuck in Europe. From the Solomon Islands to the shores off Hawaii, the British and French navies would try to bring each other to heel through cargo grabs and fast bombardments, nabbing whatever ports and facilities that were not under neutral protection to advance further. As colonial fronts went, this was the most annoying of them all, as the vast archipelagos of the equally cast Pacific rendered conventional sea battles into a game of cat-and-mouse hunts with accompanying hit-and-run attacks. Many cargo ships tried to form convoys to protect themselves, though such actions only served to slow them down and thus expose themselves to the warring belligerents.

For Australia and New Zealand, the arrival of the Great War to their front doors brought immediate anger. But with the newly formed Australian navy bearing so few gunships, the dangerous presence of Italian Papua, and the ongoing situation in the Indian Ocean, there wasn’t much room for anything to be done by the Australian parliament [2]. In the end, it fell on Wellington to deal with New Caledonia with its own paltry fleet of ships against Franco-Italian firepower. Unsurprisingly, the latter remained triumphant throughout the southern winter.

The rest of the British and French Pacific territories remained in a state of flux, with some island chains changing status over a number of times. The Ellice Islands swapped hands at least twice in 1905, while any ships traversing from Fiji became subject to commerce raids. Further east, the Cook Islands effectively became an administrative part of French Polynesia, along with the Pitcairns. As with the New Hebrides, local British residents were encouraged to swear allegiance to the new administrators lest they suffer punishment, yet local life for the most part remained unchanged.

But amidst all this, New Zealand tried again. In November 3rd, a takeover of Fiji’s largest island, Suva, by the French navy was only repelled due to another expeditionary force embarking from Auckland, just before the cyclone season. As with southern Africa, the choppy seas and stormy weather halted the war temporarily on both sides, yet the arriving forces did not stay idle. A new strategy was planned between the dominions in which Fiji would become the new hub for British operations in the Pacific Ocean, a counterweight that could bring the attack to both New Caledonia and French Polynesia.

As the southern hemisphere welcomed the arrival of 1906, it was clear that the game of cat-and-mouse would continue on the Pacific azure…

____________________

Notes:

Apologies for being late! The Africa part of this update took some time to put together, and it was hard to write a piece that wasn’t too complicated or too simple to understand. Even now, I feel like there were several potentially important places that were ignored for the sake of brevity (Benin and Egypt, just to name a few), which I’ll try to rectify in future updates. Same goes for the French-governed kingdom of Tahiti, as well.

[1] See post #710.

[2] For more information, see the notes on post #1434.

Last edited:

In reply to #1491

Modern Malaysia is unique in that kingship rotates between the nine families though - not an issue with Sarawak. The nation was forged by the Brooke kings will and abilities, so their family coat of arms being the same as that of the kingdom makes sense.

I'd say that even though it might be a good idea to have the proboscis monkey and orangutan as the supporters, the badger should perhaps still be somewhere. At most, relegated to the heir's coat of arms.

Edit: In regards to the story-post, this is truly far more of a world war than either one in our timeline. Only the Americas insofar lack a major front, but even there both Britain and France have their islands in the Caribbean and their slices of the Guianas.

Modern Malaysia is unique in that kingship rotates between the nine families though - not an issue with Sarawak. The nation was forged by the Brooke kings will and abilities, so their family coat of arms being the same as that of the kingdom makes sense.

I'd say that even though it might be a good idea to have the proboscis monkey and orangutan as the supporters, the badger should perhaps still be somewhere. At most, relegated to the heir's coat of arms.

Edit: In regards to the story-post, this is truly far more of a world war than either one in our timeline. Only the Americas insofar lack a major front, but even there both Britain and France have their islands in the Caribbean and their slices of the Guianas.

Last edited:

snip

https://www.google.com/amp/s/ibanpe.../7-burung-mali-beburung-the-7-omen-birds/amp/

Back then Sabah used Banded Kingfisher for their coat of arms.

https://www.google.com/amp/s/ibanpe.../7-burung-mali-beburung-the-7-omen-birds/amp/

Back then Sabah used Banded Kingfisher for their coat of arms.

[snip]

The banded kingfisher is one bird that can be a serious contender for a supporting animal or Sabahan sub-emblem, but I always thought it was mostly symbolic to the Sama and Bajau peoples only. I can see it being seriously considered for inclusion, all the same.

Another argument can be made for the Sarawak/Sabah emblem and supporters to be a lizard or a snake. Not only do these two beings prominent in some Kadazandusun myths (the snake and lizard are the two next beings created after humans), but they also symbolize continuity, eternity, and renewal through their shedding of skin. In a land that is brutalized by war, such symbolism can be a powerful tool to being people together.

In reply to #1491

Edit: In regards to the story-post, this is truly far more of a world war than either one in our timeline. Only the Americas insofar lack a major front, but even there both Britain and France have their islands in the Caribbean and their slices of the Guianas.

Keep in mind that there were colonial fronts in Africa and the Pacific in WWI; the German forces in modern-day Tanzania fought all the way till 1918 and the abdication of the Kaiser, for one. Here, the colonial war is fought between the world's two largest Great Powers with considerable colonies across the world, so the scope of the conflict is upscaled immensely. The Caribbean and South America are a part of this, but the fighting there is less heated than other regions due to attentions elsewhere and the fear of provoking the United States.

Now with (most of) Africa and Oceania settled, the first year of the war could be wrapped-up in the next update. Then, it's back to Sarawak.

EDIT: Speaking of coat-of-arms, I don't think I could top off this imperial wedding-cake monstrosity.

Last edited:

OTL, the fighting in Africa was a very small force with a very good commander messing things up for powers with far greater colonies powers which had few first-line troops in-theatre, but ultimately not altering the end result. It was a very interesting sideshow, but a minor sideshow nontheless. In this timeline, with the vast territories in play and in real danger of changing hands based on who controls what areas at the end, it is quite clearly a major front.

OTL, the fighting in Africa was a very small force with a very good commander messing things up for powers with far greater colonies powers which had few first-line troops in-theatre, but ultimately not altering the end result. It was a very interesting sideshow, but a minor sideshow nontheless. In this timeline, with the vast territories in play and in real danger of changing hands based on who controls what areas at the end, it is quite clearly a major front.

Good point. Speaking of which, I don't think I've made any decisions regarding Lettow-Vorbeck in this timeline, and there's a high chance for him or his atl-brother to exist as his birthdate was before Sarawak's knock-on effects deeply impact European history. He was posted to German Sudwestafrika in 1904, but given the heightened tensions he could've easily be reposted to Kamerun or Equatorial Sudan, which would make for an amusing repeat of history.

Also, I removed the spoiler for the map as I don't think the image would be too large to break any monitors. I hope.

EDIT: Also, please pay no attention to the typos on the map.

Last edited:

I just read your post on the Anglo-Dutch treaties of 1870, There you mentioned that the Ghanese forts remained in Dutch hands at that time. Looking at the African map The U.K must have still aquied them at a later point. Could you please show me where you mentioned this, please?

I just read your post on the Anglo-Dutch treaties of 1870, There you mentioned that the Ghanese forts remained in Dutch hands at that time. Looking at the African map The U.K must have still aquied them at a later point. Could you please show me where you mentioned this, please?

After searching high and low for the last hour, I've come to the sobering result that I haven't written anything about the Dutch Gold Coast and its handover to Britain in any of the Africa updates. Piecing together the acquisition won't be difficult, though; despite being a recruitment centre for the Netherlands East Indies Army (also known as Belanda Hitam/Black Dutchmen to the locals) and a point of prestige, the colony had not been profitable for decades. Rising British interests in the region coupled with a Dutch change in government resulted in both sides agreeing to exchange several border forts to formalize their territories in the mid 1870's, which backfired spectacularly by pissing off enough local tribes that Amsterdam finally decided to wash their hands off the matter and give up the colony by 1879. How does that sound?

This sounds fine. Your excellent rich story is a bit a DEI screw, so this would fit well. (OTL is IMO a DEI wank, so that is fine)After searching high and low for the last hour, I've come to the sobering result that I haven't written anything about the Dutch Gold Coast and its handover to Britain in any of the Africa updates. Piecing together the acquisition won't be difficult, though; despite being a recruitment centre for the Netherlands East Indies Army (also known as Belanda Hitam/Black Dutchmen to the locals) and a point of prestige, the colony had not been profitable for decades. Rising British interests in the region coupled with a Dutch change in government resulted in both sides agreeing to exchange several border forts to formalize their territories in the mid 1870's, which backfired spectacularly by pissing off enough local tribes that Amsterdam finally decided to wash their hands off the matter and give up the colony by 1879. How does that sound?

Threadmarks

View all 145 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Perkahwinan of the Rajah: mini-afterword Mid-Great War: 1906 - Arabian Peninsula Mid-Great War: 1906 - Africa Mid-Great War: 1906 - Oceania 1906 summary: part 1 / 2 1906 summary: part 2 / 2 Interlude: An Eclipse of Change (1907) Late-Great War: 1906-1907 - East Asia and the Russian Far East

Share: