Hmm a interesting approach to the CSA I admit quite curious not only how it develops but how it affects the world I very much do agree it won't be a wank but the CSA would be a very large nation in the world naturally it would have some soft power and influence how other nations see things.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

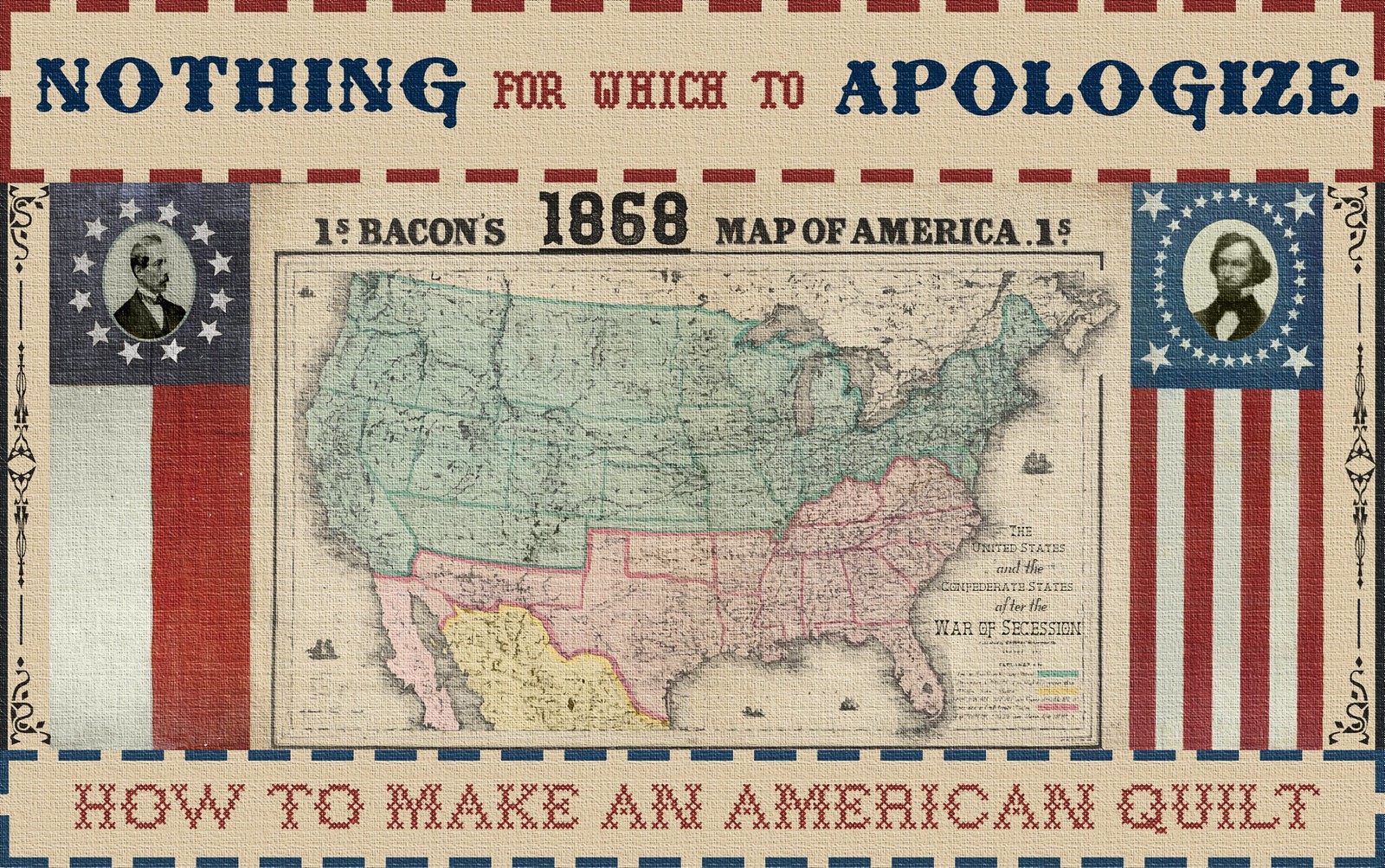

Nothing For Which to Apologize: Ambition and Loathing in the New South

- Thread starter dcharles

- Start date

I should think the interior cities of Georgia and Alabama would form one vast workshop.Very interesting developments--though, of course, morally repugnant. Interesting references to Mexico there as a refuge for the "contraband". Birmingham, AL, I imagine, is going to be a center of industrial slavery ITTL.

I wonder how useful the slaves would be as skilled, rather than unskilled, laborers--the Nazis, historically, used skilled Czech and French machinists in the forced labor camps.

Regarding the slave as an industrialist, Kathleen Bruce's research into the antebellum record-keeping of Richmond's Tredegar establishment is quite illuminating:

...

dcharles

Banned

Well, the CSA accounted for 8% of total US manufacturing output (according to 1860 census), below *Massachusetts*.

According to Kennedy, the US' share of world manufacturing output in 1860 was 7% - this means the Confederate's share was only two-third of a percent. In comparison, Italy's share was 2.5%. So it was not in the neighborhood of Italy, let alone Austria-Hungary.

I'm going to be going over my notes more completely over the next several days, so I'll try to dig up my old work on the subject as soon as I can, and when I do, I'll give you a fuller response. Like I said, I did the research several years ago, so my memory is fuzzy, but I'm sure I used Kennedy when I was compiling it. I remember writing in the book, as a matter of fact. But I do have one of the sources I used close to hand, so I'll quote a passage from that while I'm getting the rest of my shit together. (Thanks for your patience)

"As a cotton manufacturing region, in pounds of cotton consumed, the slave states ranked behind the North, England, and France but above Austria-Hungary, Belgium, Spain, and Finland. The region's carding and fulling mills, plantation spinning houses, rope walks, jute and burlap weavers, and home industries were a vital element in domestic supply. While Southern spindles were far fewer than those of the North, they were generally newer and more cheaply operated. A contrast with Britain in 1860 is instructive. British mills held about eight times as many spindles as those of the United States but produced only about four times as much cloth. The South held about the same relationship with the North. " Harold S. Wilson, Confederate Industry, (Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2002) xvi-xvii.

And also, it's less important exactly where the Confederates start out from than it is that they value industrialization, have shown an OTL willingness to pursue an industrialization program, have the money to complete such an endeavor, and that there be economic incentives that reward them to continue down the path.

Concerned Brazilian

Gone Fishin'

I also thought of ManchukuoConsidering the CSA here is industrializing slavery and all that, how would the Confederacy's use of slaves in its industrial development compare to the main OTL examples of industrialized slavery (the Nazi use of foreign laborers to fuel their industry to free up more German men for the front, the Soviet usage of gulag labor in their industrialization, and the Japanese using Chinese forced labor to industrialize Manchukuo)? I imagine that Manchukuo might be the best OTL analogy in how Confederate industrialization in many ways is similar in how both systems would use industrial slavery to rapidly industrialize from near-scratch.

As somebody who famously plays footsie with the “CSA as Giant Guatemala” trope, I will be very curious to see where you go with this. Watched

dcharles

Banned

As somebody who famously plays footsie with the “CSA as Giant Guatemala” trope, I will be very curious to see where you go with this. Watched

And frankly, your work was one of the things I had in mind when I said that the CSA as banana republic trope isn't always bad. I've been a fan of Cinco de Mayo for a long time now. Sequel de Mayo is open in another tab, in fact. I hope you see something you appreciate here.

Last edited:

You’re too kind!And frankly, your work was one of the things I had in mind when I said that the CSA as banana republic trope isn't always bad. I've been a fan of Cinco de Mayo for a long time now. Sequel de Mayo is open in another tab, in fact. I hope you see something you appreciate here.

Now Im imagining how the CSAs would react to each other

That would be a great timeline! The actual CSA from 1861, the actual CSA from 1865, the CSA that exists in the imaginations of Lost Causers, and various CSAs from different AH timelines all get ISOTed to a virgin Earth.

raharris1973

Gone Fishin'

CSA: Into the Dixie-VerseThat would be a great timeline! The actual CSA from 1861, the actual CSA from 1865, the CSA that exists in the imaginations of Lost Causers, and various CSAs from different AH timelines all get ISOTed to a virgin Earth.

Duff Green (the forgotten father of the Transcontinental Railroad) being able to establish his Southern 'industrial agency', first suggested in 1861 to 'sufficiently unite the planting and Railroad interest of the Confederate States', and successfully advance other material enterprises has always interested me had the Confederacy survived:

It was to be hoped, in the phrasing of Edward King (The Great South), author of that disagreeable yet equally-informative work of 1875, that unlike IOTL, the success of an Industrial Agency would secure investment and immigration to the South:

"The growth of manufactures in the Southern States, while insignificant as compared with the gigantic development in the North and West, is still highly encouraging; and it is actually true that manufactured articles formerly sent South from the North are now made in the South to be shipped to Northern buyers.

There is at least good reason to hope that in a few years immigration will pour into the fertile fields and noble valleys and along the grand streams of the South, assuring a mighty growth. The Southern people, however, will have to make more vigorous efforts in soliciting immigration than they have thus far shown themselves capable of, if they intend to compete with the robust assurance of Western agents in Europe. Texas and Virginia do not need to exert themselves, for currents of immigrants are now flowing steadily to them; and, as has been seen in the North-west, one immigrant always brings, sooner or later, ten in his wake. But the cotton States need able and efficient agents in Europe to explain thoroughly the nature and extent of their resources, and to counteract the effect of the political misrepresentation which is so conspicuous during every heated campaign, and which never fails to do those States incalculable harm. The mischief which the grinding of the outrage mill by cheap politicians, in the vain hope that it might serve their petty ends, at the elections of 1874, did such noble commonwealths as Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi, can hardly be estimated.

The Italians have been favorably looked upon by the Southerners as possible immigrants, and many planters in some of the States have offered them liberal inducements to settle on the lands which now lie wholly uncultivated; but it will probably be some years before any considerable body of Italian settlers take up those lands. Many foreign immigrants show an indisposition to settle among the negroes, and an especial unwillingness to accept the wages offered them by the old school of planters--namely, a trivial sum yearly, and the rations of meal, pork, and molasses, with which the negro is easily contented. The immigration question can only be settled by time; but an exposé of the material resources of the South is an important aid to such settlement, and I have endeavored, in the foregoing pages, to give some adequate idea of those resources, and the possibility of their development. The attentive reader of this book will not fail to discover that the mineral wealth ascertained since the war to exist in some of the States of the South is likely to be of far more importance to their future than all the broad cotton-fields, once their sole dependence.

Until her people have recovered from the exhaustion consequent on the war, capital is and will be the crying want of the South. The North will continue to furnish some portion of that capital, but will be largely checked in its investments in that direction, as it has been heretofore, by its lack of confidence in the possibility of a solution of the political difficulties..."

It was to be hoped, in the phrasing of Edward King (The Great South), author of that disagreeable yet equally-informative work of 1875, that unlike IOTL, the success of an Industrial Agency would secure investment and immigration to the South:

"The growth of manufactures in the Southern States, while insignificant as compared with the gigantic development in the North and West, is still highly encouraging; and it is actually true that manufactured articles formerly sent South from the North are now made in the South to be shipped to Northern buyers.

There is at least good reason to hope that in a few years immigration will pour into the fertile fields and noble valleys and along the grand streams of the South, assuring a mighty growth. The Southern people, however, will have to make more vigorous efforts in soliciting immigration than they have thus far shown themselves capable of, if they intend to compete with the robust assurance of Western agents in Europe. Texas and Virginia do not need to exert themselves, for currents of immigrants are now flowing steadily to them; and, as has been seen in the North-west, one immigrant always brings, sooner or later, ten in his wake. But the cotton States need able and efficient agents in Europe to explain thoroughly the nature and extent of their resources, and to counteract the effect of the political misrepresentation which is so conspicuous during every heated campaign, and which never fails to do those States incalculable harm. The mischief which the grinding of the outrage mill by cheap politicians, in the vain hope that it might serve their petty ends, at the elections of 1874, did such noble commonwealths as Alabama, Georgia, and Mississippi, can hardly be estimated.

The Italians have been favorably looked upon by the Southerners as possible immigrants, and many planters in some of the States have offered them liberal inducements to settle on the lands which now lie wholly uncultivated; but it will probably be some years before any considerable body of Italian settlers take up those lands. Many foreign immigrants show an indisposition to settle among the negroes, and an especial unwillingness to accept the wages offered them by the old school of planters--namely, a trivial sum yearly, and the rations of meal, pork, and molasses, with which the negro is easily contented. The immigration question can only be settled by time; but an exposé of the material resources of the South is an important aid to such settlement, and I have endeavored, in the foregoing pages, to give some adequate idea of those resources, and the possibility of their development. The attentive reader of this book will not fail to discover that the mineral wealth ascertained since the war to exist in some of the States of the South is likely to be of far more importance to their future than all the broad cotton-fields, once their sole dependence.

Until her people have recovered from the exhaustion consequent on the war, capital is and will be the crying want of the South. The North will continue to furnish some portion of that capital, but will be largely checked in its investments in that direction, as it has been heretofore, by its lack of confidence in the possibility of a solution of the political difficulties..."

Exemplary introduction! Very keen to see how this progresses.

Just wanted to confirm, while you said you won't be covering the civil war, can it be assumed that this Confederacy is composed only of the 11 states that officially seceded under the Confederate banner OTL? Or were there additional territorial changes?

Just wanted to confirm, while you said you won't be covering the civil war, can it be assumed that this Confederacy is composed only of the 11 states that officially seceded under the Confederate banner OTL? Or were there additional territorial changes?

Watched! I think a lot of surviving Confederacies underutilize the concept, looking forward to how this one will turn out!

"Oh! my dear brethren of the loyal North, do not taunt us with our poverty, when your own writer, Thomas Prentice Kettell, tells the world that the South gave $2,770,000,000 of her wealth to swell Northern profits. If that money were given back to us, we could get up a "big boom" sure enough, and become a veritable New South."

- Daniel H. Hill

- Daniel H. Hill

Honestly, I'd read that book.An Awakening in St. John the Baptist was a national and international bestseller, and cemented Chopin’s reputation as an important and controversial figure in the international literary scene.

Chapter 2: How to Make an American Quilt

dcharles

Banned

“Remember, Miss Bisland, they don’t call him Stonewall down here, down Mexico way. Down here, they calls him El Verdugo. The Hangman.”

— Robert Smalls, 1892; quoted in Elizabeth Bisland, The Mexican Dispatches; or, Conversations With the Devil of Beaufort County. (New Orleans: Dixie Free Press, 1894), 77.

“We started using the trot line in ‘65, when we was rounding th n—s up. Them n—s now, they loved to hide in a cotton field or a corn field, and afore the trot line, they’d just go in and look for ‘em all higgledy-piggledy, like. I knew that dog wasn’t gonna hunt, so we made the boys work that trot line. Very simple. You start on one side of the field, each man standing about two paces away from the other. Ever’ third one’s got a dog on a lead, ever’ ninth’s on horseback.

Some of them n—s now…they can run like jack-rabbits. But you work that trot line… with them dogs and them horses, and ever’ man armed? I tell you what, ain’t none of ‘em got away. Not from me, they didn’t.”

— Nathan Bedford Forrest, 1878; quoted in Andrew Nelson Lytle, The King of Flesh: Bedford Forrest and His Times (Sewanee: University of the South, 1943), 117.

“Say what thou wilt regarding the much discussed work ethic of the Yankee, I remember well that there was not much work done that Monday in Boston-town. Though the day after is one that shall dwell in gloom for all times, on Monday we had no way of knowing what would come, and all was gladness and good cheer. That Tuesday, was of course the Republic’s eighty-ninth anniversary–always a time of great merriment in Boston–but it was also when President McClernand was due to return to fair Columbia’s hallowed ground, fresh from the signing of the Peace Treaty in Halifax. Though it shames me to admit it now, I was no great admirer of John Alexander McClernand in those days. My own stock is pure Yankee, and I was then but a lad of fifteen. Thus in matters of politics, I followed the customs of my clan. My own family in ‘64 had been somewhat divided between Fremont and Lincoln, with the greatest number for Lincoln. Dear reader, forgive the confession, but I must say that in a fit of youthful precocity, I myself favored the Radical. Alas, radicalism is the natural folly of the young, and though my constitution is a strong one, it was not one immune to youth itself. Nonetheless, along with the great majority of the country, I had resolved to abide the election with good order. At last, we would have peace. At last, our brave soldiers would return to the bosom of family and the comforts of hearth and home. After so much bloodshed, the irrepressible conflict was finally laid to rest.

I had been admonished by my father, who had a wisdom that I then lacked, to stay well-clear of the harbor when the Kearsarge came into port. But as surely as Tuesday follows Monday, the ship arrived, and I was bested by temptation in my callow foolishness. The sun shone gently in a crystal sky, a cool and steady breeze blew in from the Atlantic, and the enthusiasm of the people buoyed me along as I made my way to the docks, for even in bustling Boston, the arrival of the President is not a commonplace. The crowds there were quite immense, and it took me better than an hour to squeeze and excuse my way to the front, though I immediately made the endeavor my highest priority. As we waited for the ship to arrive in nervous excitement, I spied a longhaired young man in the crowd sporting a growth of auburn beard. The feature of his countenance that attracted my notice was his right eye, which was milky, as if blinded. The youth muttered to himself but engaged no one in conversation. From his age, as well as his demeanor, I ascertained him to be a veteran of the late war, perhaps addled from the rigors of battle, but I detected no hostile intent. So innocent was I that I still held fast to the notion that a scoundrel would appear an angry brute in the moments before his dastardry. Of this notion I would be shortly disabused.

It has been said, and I have heard it confirmed by the greatest authority, that Seymour–who was unbeknownst to himself, nearing the end of his term as Vice President– advised President McLernand to avoid disembarking in Boston, fearing the Radicals there held too much sway:

‘Now Seymour,’ replied McLernand, ‘don’t come down with a case of the all-overs! This is no time to be spooked. The Democracy polled sixty-five thousands of votes in Massachusetts, and at least a few came from Boston. O! Take heart, for there are peace loving men in that city yet.’

As the Kearsarge sidled up to the dock, the crowd endeavored to prove the great man correct, and erupted in applause and congratulations. With the harbor-master shouting commands into a great tin bullhorn and the muscled longshoremen sprinting to and fro, hoisting the gangplank and tying off the ship, the atmosphere was one of vitality and anticipation. Radical though my naive heart may have been, I found the ebullience infectious, and joined in the cheering along with all the rest. As the President and his party descended down the gangplank, the band struck up a smart rendition of ‘Hail to the Chief.’ The cacophony was tremendous, but amidst the noise I perceived that the young man with the auburn beard had moved immediately to my right. Had it not been for that quirk of fate, I would not have heard the words he said as he pulled the Colt from his jacket and took aim at the President.

‘No peace with the slave power!’ cried the knave.

The assassin, one Francis Jackson Meriam–a fanatical disciple of the late, deranged John Brown–was able to fire only one shot before the crowd beset him, but the lone bullet was sufficient for his devilish object. President McClernand, who was still on the gangplank, was shot in the left side of the throat. As his hand clutched at his wound and made to stanch the bleeding, he lost his balance and tumbled into the dirty water below. In a flash, one of the longshoremen dove in after him, braving the rocking of the ship’s mighty hull to save the fallen chieftain. The crowd surged forth as one inexorable tide, crowding the water’s edge to catch sight of the President and his rescuer. When the longshoreman’s head broke the surface of the water, a spark of hope alighted in our breasts. Alas, we were soon able to apprehend that the President, while in tow, was limply slumped to one side, his face well below the water’s surface. The wound was mortal, and shortly after McClernand was recovered, it became apparent to us all that he had expired.

Boston burned that very night…”

— Rep. Henry Cabot Lodge, “July 4th, 1865, An Eyewitness Account; or, How I Joined the Democracy,” Scribner’s Magazine, 1, no.1 (1887): 24-26

“Long eclipsed in the popular mind by the silhouette of the great Beauregard, the Provisional President of the Confederacy is often reduced to an object of trivia in the chronicles of early Confederate history. When Jefferson Davis is considered at all, it is most often as an object of scorn. Even in the most favorable accounts, Davis is a civilian in a time of generals, whose strategic contributions to the great issue of the day–the Confederate Revolution–were minimal. As this work will show, much of the criticism directed towards Davis is deeply personalist and reductionist. At times, it is unfairly anachronistic. Too often, the years of Davis are unfairly reduced to one event: the 1866 hanging of the erstwhile Confederate partisans and bandits William Clarke Quantrill and Bill Anderson in Arkansas for crimes committed in Missouri, a foreign jurisdiction. While few, including myself, would defend the political wisdom or legal basis[1] for the execution–for which Davis avoided impeachment by the skin of his teeth[2]–the historian must beware not to throw the baby out with the proverbial bathwater.

In truth, the Davis legacy is more complex. Many of the criticisms leveled today are anachronistic. While it is true that the borders negotiated in the Treaty of Montreal[3] were the source of much future mischief, it was widely hailed at the time, and it is doubtful that anyone else could have negotiated more astutely. After all, no partition in history has been without its complications, and while the rebellious Allegheny counties of western Virginia may have been a wellspring of unrest in the Confederacy, it is equally true that Maryland’s eastern shore and the state of ‘Bloody Missouri’ were centers of discontent in the US.[4] Although Southern historians are finally reckoning with the collateral damage associated with Davis’ policy of remandment, it is important to recognize that the many of the estimated 20,000[5] Negroes who perished in the camps died from disease, and many of the camps’ worst excesses are attributable to individual camp Commandants such as Harvey Hill and Bedford Forrest. Crucially, the historian must also acknowledge that while the calculus of remandment was cold and caused undeniable emotional scars, the ‘Black Terror’ of the Contrabands was no exaggerated threat. In many ways, Davis’ hand was forced on the matter by the wartime incitements of a pair of Union generals, the radical abolitionist David Hunter and the loathsome William T. Sherman (the very same who would soon prove to be more bloodthirsty an Indian killer than Cortez). It was they who supplied the weapons and training that sustained the Contrabands during the armistice period, and it is at their feet where much of the blame for the remandment policy must be laid.

Many other criticisms, while not anachronistic, have been exaggerated. While no reasonable historian would contend that Davis’ relationship with the Confederate Congress was affectionate, it is a mistake to project the seething antagonisms which came to a head in the final years of the Davis administration onto its first years. Indeed, it is important to remember that prior to his near-impeachment, Davis won the two largest fights with Congress during the armistice period–the confirmation of Benjamin to the Supreme Court and the Transcontinental Railroad bill. It is not Davis’ fault that the Kenner Act, which provided for the Transcontinental Railroad, was delayed by litigation and (in its original form), eventually overturned on a technicality. Davis, in contrast, should be credited for the achievement of passing the bill even before the secret negotiations for the California Purchase had been concluded or made public. Furthermore, it was Davis’ decision to send the Mexican Volunteer Expeditionary Force (MVEF) to aid the Mexican Empire in suppressing the Juaristas set the stage for the negotiations in the first place. Even if negotiations were completed during the Beauregard administration, Davis deserves much of the credit for their initiation…”

—William J. Cooper, More Than Provisional: A Reassessment of Jefferson Davis (Greenville: Furman University Press, 1982), xi-xii.

[1] The rather curious argument that, since the Confederacy claimed Missouri when the crimes were committed, Quantrill and Anderson were therefore subject to Confederate prosecution.

[2] Saved from impeachment by the last minute switch of one vote, that of the young South Carolina Congressman Franklin J. Moses, allegedly purchased by Davis ally and future Secretary of State George Trenholm.

[3] Also called the Treaty of Halifax, especially in the United Kingdom. After the armistice-era failure of the Baltimore Conference, the treaty was negotiated in Montreal with British and French mediators. As Davis was loth to travel through the United States and McClernand did not want to make the arduous journey to Montreal by land, the treaty itself was signed in Halifax.

[4] Not to mention the partition of Cherokee land in what was then the Indian Territory, which became a bleeding ulcer for both nations.

[5] The assertions of the late Gregory Tarle, along with his proteges Ike Mintz and Vann Woodward, that the real death toll was between 50,000-60,000, are drawn upon a haphazard array of state, local, and oral sources. These arguments by inference are inherently unreliable. Until these numbers can be more thoroughly verified, the official records must be given the presumption of truth.

“Though he was given to stretches of purple prose in his later years, in the summer of 1865, the wiry young general’s way of speaking had been roughened by years of war, and when he took the stage at the Atlanta Odd Fellows’ Hall, he began plainly. ‘Most of y’all know me already–hell, some of y’all rode with me–but for those that don’t, know this: I rode with Jackson, and Cleburne, and Morgan. Been in so many engagements I lost count. Had five horses shot out from under me in three years of war. Cried for every one of them.’ The men laughed at that, and the newly-former general laughed along with them. He held up his left hand–all three fingers of it–and wiggled the stumps of his little and ring finger. ‘Lost those two beauties to a Yankee saber in a good-for-nothing skirmish on the outskirts of Lexington. When we struck camp that night, the country was so picked over we couldn’t find two dry logs for a fire, and we all like to froze to death.’ The Hall filled with the ayes and the amens and the rueful chuckles of men who’d been there before. ‘But everybody wasn’t living that way. We were. You were, and maybe even your families were. But while you and your families were suffering, while y’all shivered and hungered in Virginia and Kentucky, Joe Emerson Brown kept good uniforms and warm blankets locked away in Georgia warehouses.’ The young general paused for effect, surveying the audience, glaring, as if he dared someone to contradict him. The green wood of the hastily constructed stage creaked as the small man shifted his weight, and murmurs of dismay rippled through the veteran crowd as his words sank in. Joe Brown, Governor of Georgia since 1857, was nearing the end of his unprecedented fourth term and seeking an even more unprecedented fifth term. He was so powerful and unassailable in his sinecure that he’d made a habit of thumbing his nose at Provisional President Jefferson Davis, a fact to which the young general had just alluded. ‘That’s right. While you brave, outnumbered few turned the Green River red with blood, Joe Brown’s pets sat up here in Atlanta with no-show posts in the Georgia Militia, smoking cigars and drinking corn whiskey.’ The murmurs got louder. More than a few in that room had been at Morgantown and had seen the river with their own eyes.

There goes the War Child, shouted one wit in the crowd.

If it was meant as an admonition, Joe Wheeler, not yet thirty and already a storied figure from his days in the Army of Kentucky, did not take it as one. ‘While your feet bled on the gravel of the National Turnpike for want of shoes, Joe Brown impounded eight thousand pair of first rate brogans to collect dust in a Milledgeville storehouse! When the sons of the South made-do with flintlocks and smoothbores, Governor Brown hoarded rifles!’ And on he went. Members of the crowd began to whoop and holler in approval of Wheeler and scorn for Brown. Summer nights were tolerably cool in Atlanta, but the temperature in the Odd Fellows’ Hall climbed and climbed. Sputtering gaslights cut through the haze of tobacco smoke, and the meeting took on an atmosphere that was part tent revival, part dancehall. Aside from the soldiers still deployed against the Contrabands, most of the troops had mustered out and returned home. Seething with energy, they were profoundly changed from their years of war and privation, and they returned to a society changed just as profoundly. Yet the same clique of politicians who had dominated before the war and during the war still dominated. If anything, the ones in power now were ‘even greater rascals than before, for while the patriots enlisted,’ the old Whigs and ex-Unionists had found reasons to ‘stay home and cause mischief.’ As Wheeler put it to raucous applause, ‘the strong bulls went off to war, and the mangy old scalawag steers stayed in the pasture and snatched the herd for themselves.’

But things were different now. The peace treaty had been signed and ratified, the war was over, the blockade lifted, and the cotton trade was booming again. Money was being made (and was even worth something these days), but in disproportionate numbers, it was being made by the shirkers and obstructionists who’d stayed home. Aside from coining one of the memorable insults of the early postwar era–scalawag–Wheeler was giving vent to resentments that had been simmering for years and only made more acute by the months of relative peace. ‘The bulls [were] back,’ he roared, ‘fewer in number, but stronger than ever!’ With their own blood, the soldiers had forged a nation. Now that they had done so, were they going to turn it over to the truants and malingerers who had spent the war finding ways to make the soldiers’ privations greater? Never! came the cry from the hall. But who could lead them? ‘Who could hold the torch for the New Georgia and the New South?’

The soldiers could only trust one of their own–the kind of man who had spilled blood and whose blood had been spilled, who had endured the same years of hardship and brutality that they had. ‘The kind of man,’ exhorted Wheeler, ‘like Georgia’s own, General John Brown Gordon.’”

Vann Woodward, War Child: Joe Wheeler, John Gordon, and the Origins of the New South Party. (New Orleans: Free University Press, 1969) 12-13.

CONSIDER THE FACTS

“In the Negro sections of Monterrey, a ghastly rumor has arisen over the past many years; a legend of savagery so cruel and shocking I would scarcely believe it had it not been corroborated by so many. The tales were first told to us by the vaqueros returning to Mexico from cattle drives into the Confederacy, and later by certain Negroes who’d managed to flee south, of a ghoulish sight that appeared with oppressive and surprising regularity in the slaver’s frontier. In Texas, Arizona, and Confederate California, countless witnesses have obeserved the same: the body of a Negro, usually a man, the eyes put out with something hot, the tongue cut out with something sharp. Sometimes the corpses are in twos and threes, but they are usually found alone. At least two of the wretches have been found alive, but both succumbed to their wounds shortly thereafter. I have been able to confirm more than three dozen discrete sightings of bodies in such condition, though the reports of such are nearly innumerable…

…Until now, the motivations behind the murders have been unclear. The bodies seemed too widely dispersed to be the work of one depraved madman, but the mode of dispatch was unvarying. The only apparent commonality was that the victims were all Negroes, the bodies were usually found close to a railroad, and that the train cars of Forrest & Son had recently passed through that country…

For the first time, a witness to the ghastly practice speaks of what he has seen… A.P., a former overseer for Forrest & Son now living in Confederate California, tells of the barbaric work of the BEDFORD MANUMISSION…”

—Ida B. Wells, “The Kindly Masters of Forrest & Son,” Monterrey Free Beacon (Monterrey, NL, Mexican Empire), Feb 13, 1882.

“These days, no matter which side of the Rio Grande you find yourself on, chances are you’ll find your way to a Salma joint before too long. Who could resist the temptations of a mouthwatering plate of carnitas Confederadas or a fiery red drumstick of pollo demonio? But in between bites, ask yourself–how much do you really know about the history of Salma?

1) Salma didn’t used to be called Salma.

As a matter of fact, it wasn’t until the 1970s and 80s that people started to call it Salma at all! The original English term was actually N—ito chow (or simply N—ito), which is considered impolite today. Even the use of the Spanish Negrita can be easily misheard, so it’s probably best to go with Salma. Still, N—ito is a common enough word to encounter, especially in some of the older restaurants, so don’t let it scare you away. Just don’t call it Afromex!

2) Salma has kind of a dark history.

Salma is one of the more recent entries into the international culinary scene, and there’s actually good reasons for that. After the Confederate Revolutionary War, the United States enacted two laws, the White Immigration Amendment, which barred all nonwhite immigration, and the Negro Expulsion Act, which provided for the expulsion of black war refugees. Although enforcement of the Expulsion Act was spotty and the Exclusion Amendment only applied to immigrants, thousands of blacks nonetheless fled to Canada, the American West, and Mexico, establishing especially vibrant communities in the cities of Veracruz and Monterrey. Over the decades, the initial wave of migrants was joined by runaway Confederate slaves, especially young men working on the Transcontinental Railroad. Before long, a fusion of black cuisine and Mexican cuisine began to develop, and by the 1930s, Salma had emerged as its own unique tradition, with its own canon of recipes and techniques.

3) The word “Salma” is a portmanteau!

That’s right! Much like the cuisine itself, the word Salma is a mashup. As n—ito fell out of favor, food writers and chefs searched around for something to replace it. Although “Afromex” saw a bit of use, many black people rejected it, feeling that it played into old ideas that the proper place for black people was back in Africa. And so Salma, a mixture of the English and Spanish words for “soul,” was born.

4) Salma used to be hard to find north of the border.

Though it might be the most popular food in the South now, it wasn’t until decades

after the abolition of slavery that many black Mexicans felt comfortable returning to the South….”

—Allrecipies.com staff, “10 Spicy Things You Did NOT know About SALMA!” allrecipies.com, September 10th, 2021. allrecipes.com/10-spicy-things-about-salma/

Last edited:

Share: