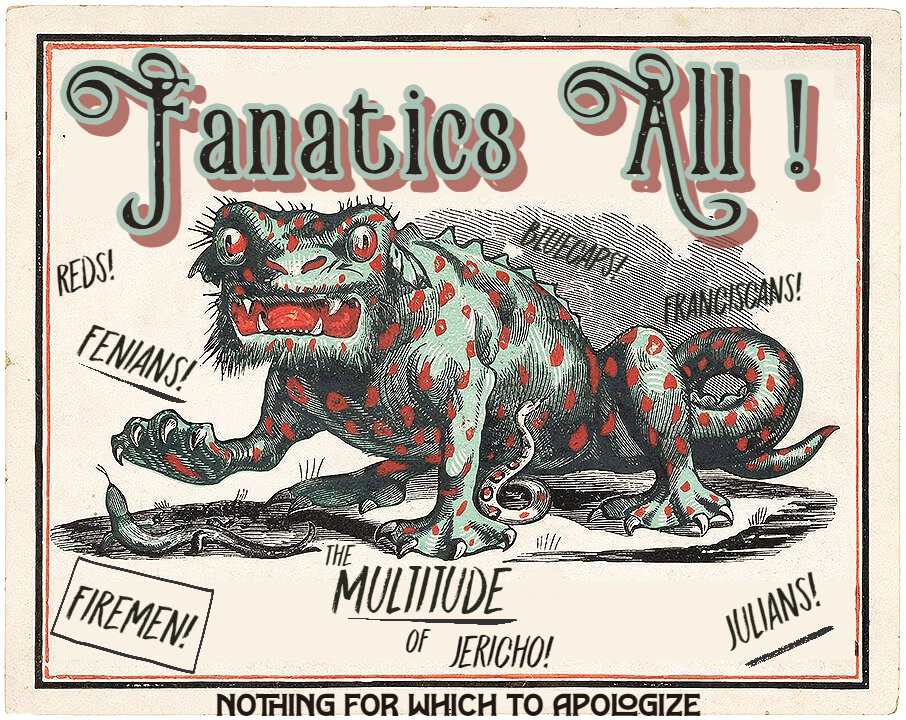

Chapter 6: Fanatics All!

"I have heartache, I have woe,

I have trouble here below.

While God leads me I'll not fear,

I am sheltered by God's care."

---Traditional, "Every Time I Feel the Spirit," quoted in Moe Asch, Voices of Discontent. (New Orleans: Free University Press, 1951.)

“At last, we are a nation of cranks and imbeciles, to say the least! Zealots, visionaries, and fabulists–you may take your pick of the lot, for we have every sort in ample supply. In these times it is a simple inevitability that a man will be taken in by some humbug and will follow some faction, which will work to the advantage of none and the aggravation of all. If a man is not a warmongering Franciscan or Fenian, he is probably a free lover, or a spiritualist, or a vegetarian, or a subscriber to some other manner of hokum and quackery. Every Julian pogrom is balanced by a Red riot, and every dour Temperance man is countered by a jolly good fellow of the Hibernian Order. There are the Knights, a group of serfs who call themselves squires. There are the Grangers, a group of hayseeds who want money to be devoid of value, and there are the anarchists, a group of malcontents who want property to be devoid of proprietors. Arrayed against them are the capitalists who would have us all be their debtors, the Copperheads who dream of the reconstruction of the Union as it was, and the Goo-Goos who think that democracy might be a fine thing if it were somewhat denuded of the elections and especially, the voters who vote in them. Meanwhile, the political parties, with all the discernment of a public woman plying her trade about the town, court every combination, clique, syndicate, ring, and gang in the country, so long as they number at least a dozen, and are fanatical or venal enough to whip their fellow fanatics to the polls.

Fanatics all, I say, and thus a pox on all our houses.”

—Mark Twain, “Fanatics All!” Puck, October, 1878, 12.

THE HOTTEST OCTOBER ON RECORD

“The cotton gins of Memphis are filled to bursting in late October. The accumulated produce of a season’s harvest is stacked to the rafters of the city’s warehouses, and stray cotton bales are liable to be found stashed in any hayloft or horse stall big enough to accommodate for a week or two. Every year more than the last, the city is entirely flush with activity, swarming with speculators and counter-speculators, the population swollen with the very same rented Negroes who had picked the very same cotton from the fields of Mississippi in the weeks before. This year, after the September Scorching and an August Aflame, the city patrols prowled the streets alertly, and the detectives of the Directorate skulked about the shanties of Memphis and West Tennessee for evidence of the subversives who had already put so much of this year’s crop to the torch.

Of all the needles in all the haystacks, these have proven to be the most elusive, though not for lack of trying. Throughout the Negro section during the month of October, shanty doors were kicked off their leather hinges by the boots of paddy rollers. Lashings were doled out liberally. Barracks were tossed, families hustled onto the streets, and the meager possessions of Tennessee’s humblest ransacked, searched, and destroyed in the hunt for any clue which might connect the inhabitants to the Firemen, the late scourge of the ‘85 cotton crop. If any unrelated contraband was found, so much the better, went the logic. Bass Reeves was one thing, but the good citizens of Memphis all agreed, the Negroes were more uppity than ever; even worse, said many, than they had been during the Terror of ‘65.

As the events of last week showed, it was all to no avail. Despite the persistent and brutal efforts of the Confederate gendarmes, three-quarters of Memphis now lies in ashes as a result of a conflagration the likes of which has not been seen on this continent during a time of peace. Already it is being called the Great Memphis Fire, and the death toll, as best as can be ascertained, stands at three hundred and counting, with the homeless numbering in the scores of thousands. Even on preliminary observation, it is reckoned to be the costliest disaster in the history of Tennessee, if not the Confederacy itself. The loss of the cotton alone represents millions, to say nothing for the value of the real, personal, and industrial property destroyed by the blaze. The origin of the fire remains in some dispute, and is under investigation. While the Directorate states that the Cotton Exchange seems to be the single origin point, Mayor Hadden has publicly contradicted them, insisting that fires were set at multiple points, which has fueled speculation that the Great Memphis Fire was the handiwork of the Firemen or some like-minded group. As of this printing, the Firemen, who have always claimed credit for their attacks in the past, have not done so with respect to the blaze in Memphis. If the Firemen are indeed responsible, it would represent a marked escalation in the scale and ambition of their operations, as they have previously preferred smaller, isolated targets such as mines, riverboats, cotton fields, and plantation gins…”

—Ida B. Wells, “Smoke and Rumors in Memphis,” Monterrey Free Beacon (Monterrey, NL, Mexican Empire), October 29th, 1885.

“...a methodical examination of the national membership rolls in the years of 1866-72. Gosnell and Burnham found that the oft-repeated charge that the Julian League was the ‘brass knuckles of the Democratic Party’ to be mildly overstated. While it is true that Democrats predominated in the membership on a nationwide basis, the nationwide story was not the whole story. In areas where the primary electoral competition was between Radicals and Republicans, such as New England and some areas of the West, Republicans and Freemasons were well represented within individual lodges, even if overall membership in those states was lower. In areas where the primary competition was either between Democrats and Republicans, or were contested by all parties, Democrats predominated. Everywhere, veterans made up a majority or a plurality of the membership. In an era characterized by its bitter partisan conflicts, the Julian League, committed to the principles of 'Americanism' and white supremacy, was one of the few bipartisan (though not tripartisan) organizations active on the postwar political scene…

Perversely, membership in the Julians skyrocketed in the wake of the Cherokee Street Massacre of November 1866. There, an interracial march of German-Americans and free blacks, led by Colonel Joseph Weydemeyer, a leading St. Louis Radical, was set upon by a mob incited by General Frank Blair Jr, the first High Chief of the League and future governor of Missouri. Although the death toll stood at thirty-one, the Radicals, who were engaged in a peaceful march in a friendly neighborhood and were therefore largely unarmed, took the brunt of the casualties by far, with nineteen marchers and five German-American bystanders killed…

…ecumenicalism sowed the seeds of its demise. The postwar conflicts surrounding questions of abolition, pensions, poll taxes, and Negro immigration receded. The thousands of workers laid off from the textile mills of the Northeast and the veterans returning home eventually found work and fellowship elsewhere. The League’s primary organizers and figureheads, High Chief Frank Blair and Grand Chieftain John Logan, respectively, went on to an early demise and a presidency that would be consumed by scandal and war. Finally, in the throes of a slow and painful death, the Republican Party shrank from a second party to a third, and eventually, to a strictly local concern, and the League lost even its bipartisan luster. After successive years of record-breaking immigration from Europe–especially southern and eastern Europe–nativist sentiment once again rose to a fever pitch. Inevitably, those who could, as the battle-cry went, ‘remember the Fourth,’ became fewer and fewer in number as the years went on. By 1900, the League for the Solemn Remembrance of the Fourth of July, which had boasted of more than a million members at its 1871 peak, was reduced to a little more than a thousand active dues payers.”

— David W. Blight, A Hue and Cry From All Corners: The Painful Birth of the Second Republic, 1865-1876 (New York: Scribner, 2001) 61-70.

“...and I saw that mine was not the only white face in the bleeding heart of Congo Square. When the primeval rhythm of the bamboula had altogether permeated the crowd, the three drummers beat a crescendo into the air with a mighty flourish before coming to a deathlike halt. At once, the gyrating horde of bodies akimbo fell to the ground, stilled. Silence descended and a pathway appeared amidst the multitude. With an air of humble solemnity, the peddlers doffed the palm fronds shading their white curtained stalls and laid them upon the path. The merciless morning sun amplified the quietude, burning it into the air, until the only sound which could be apprehended was the slow crunching of palm leaves under the soles of a big man’s feet. Arms aloft and outstretched, a tall Negro approached in a broad black hat, wearing an ancient frock with lapels so high I first mistook it for a Roman cassock. As he arrived in our midst, his arms moved into a slow clap, marking time, and he began to sing “Ev’ry Time I Feel the Spirit” in a rich, fulsome baritone that started in a husky whisper before expanding to fill the silence. He moved through the first verse, brow already gleaming with sweat, his voice pushing aside the noise from the street. The crowd began to rise, one supposes, as they began to feel the Spirit; when likewise moved, they clapped time and sang along. Lest the apparent spontaneity fool the observer into thinking the scene chaotic, after three or four verses the maestro’s clapping hands balled into sable fists and silence reigned once more.

‘Today you are first, praise God!’ cried the man in black.

The answers came in all accents and dialects: ‘gloire à Dieu!’ from the créoles noires and the coloreds, ‘hosanna!’ and ‘praise Jesus!’ from the English speakers (who were mostly Negroes, but with a handful of rawboned crackers, too). The various permutations of adoration, glory and alleluia were favored by all, but especially by the Cubans and the Sicilians, who both numbered rather more than a handful, and were only distinguishable from one another (and many of the coloreds) by the particular lilt of their chatter.

On the streets of New Orleans, the man in black has almost as many names as there are tongues among the crowd. Though he is most commonly known as Papa Will, one might encounter Daddy Bill or Doctor Corb’ [1] nearly as often, and there are half a dozen more that prevail in mere sections of neighborhoods here and there in various wards of the city. The first two, at least, correspond reasonably well to his given and government names, and the last is both an allusion to his sartorial preferences and a knowing wink to his reputation as a sometime curandero, or something approximating one. All three are uncommon monikers for one so young, and his apparent maturity only adds to his mystique.

As is the case with many of his class, the circumstances of his ancestry are seen only, as the Apostle Paul described, as if through a glass, darkly. His beginnings as a preacher are no more clear; the stories are as numerous as they are contradictory. Is it true, as it is said, that he won his family’s freedom after healing his former master by work of faith alone? Or was it the case, as it is also said, that it was instead his gifts of prophecy that saved the man? And what of the rumors, altogether more salacious, that Seymour’s parents–to say nothing of the man himself–had no legitimate cause to be in the city at all, that they were merely two amongst the tide of fugitive refugees–nay, Contrabands–who arrived in the city during the dark years of occupation and revolution?

As best as this reporter can divine, William Seymour, the man in black, was born free in the city sometime in early May of 1870, with baptismal records at the parish of St. Augustine dated to the tenth of that month. If it is true that his parents were fugitives, the wise magistrates of Gallier Hall have no record of the prosecution of such a claim, and the inquiries of the incorruptible Inspector Siringo and the other brave and efficient officers of the Directorate have found no basis for further investigation. It is unknown when he learned to read or by whom he was taught, only that he was, by ‘88, of some renown as a preacher, and was well known to be engaged in that occupation by the merchants and denizens of Elysian Fields. Seymour himself claims that the gift of prophecy came to him as early as the age of six, when he foretold the sudden death of Francois Lacroix, the old eminence-grise of the free colored community. But the first such event which was publicly accounted for was his foretelling in the preceding September of the Great October Storm of seven years past. It was his charitable efforts in the wake of that disaster that sealed his reputation; the first sermons in Congo Square began shortly thereafter. Indeed, one might speculate that the indulgence heretofore shown to Papa Will by the authorities was paid for one bowl of gumbo at a time, passed out in the dark days following the storm and deposited c/o the hungry multitudes from his stand on Canal Street.

“Can you feel it?” he exhorted, and the answers of the people left no doubt. The Spirit was moving, and all could feel it. “The New Pentecost is at hand!”

The gumbo ya-ya [2] around Basin Street says he has never preached to a sparse crowd in Congo Square–such was his reputation as a healer and prophet that when he made his calling known, he already had the beginnings of a congregation. The gumbo ya-ya upriver of Canal grumbles that he is simply another charlatan Voodooist vying for whatever is left of the late Widow Paris’ invisible empire of superstition. The Baptists say that if he is not a Voodoo, he is a Catholic, which is almost as bad. With some justification, the priests counter that a Negro lay preacher’s reliance upon the Douay-Rheims and his veneration of Catholic saints does not constitute an endorsement by the Church of Rome. Privately and publicly, many of the clerics worry at his influence, but there are many still who feel that Papa Will’s sermons have a salutary effect on the frailties of the African moral constitution, helping to guard against the perpetual tendency within that race to revert to the darkest heathen practices of Old Africa.

Faithful readers of this column well know of my own long reconnaissance into the circles of the Voodooists. The display I witnessed in Congo Square bore none of the most grotesque hallmarks of that barbaric sect, though the ecstatic mood of the worshippers was reminiscent of such as I have witnessed in their rites. There were no serpents to be worshiped, no cockerels to be sacrificed. There was ebullient dancing, as there always is when more than a half dozen Negroes congregate, but it was not wanton, and no one was nude. While his demonstrations of healing by faith are regarded by cynics as the cheapest charlatanism, Papa Will asserts that the faithful are healed not through blood sacrifices to devious gods, but by the power of Christ alone, and justified upon his interpretation of the Book of Acts. Furthermore, he insists that this power is one to which all Christians may avail themselves should they be baptized in the Holy Ghost. More troubling than his purported gifts of healing or prophecy is Doctor Corb’s explanation for their appearance, which he takes to have apocalyptic significance:

“For it was the great St Peter, brothers and sisters, who told us that ‘in the last days, (saith THE LORD,) [HE would] pour out of [HIS] Spirit upon all flesh…And upon [HIS] servants indeed, and upon [HIS] handmaids’ would HE give the gift of prophecy! To the servants indeed HE would show wonders and signs, of ‘blood and fire, and vapor of smoke!’”

But whither the apocalypse to which we sleepwalk? Is it the millennium of milk, honey, and hosanna promised in the Revelation of John, or the conflagration foretold by the same, where the depredations of Smalls and Atilla shall be made to look like the mischief of children? On this point the good Doctor’s theology becomes more vague. He vacillates. In the midst of his sermoneering, he paints vivid pictures of the days to come to his audience:

“‘ in the days [of the New Pentecost,] all of them that believe and will be baptized in HIS name, my brethren, shall have ‘all things common…and divide to all’ according as we have need. For THE LORD himself hath said, on the road out from Jericho, that the people of GOD shall not be like ‘the princes of the Gentiles’ who lord over the earth! No! Among the people of GOD, the greater shall be the minister, and not he who is ministered to. Among the people of GOD, the servant shall be first, Amen!”

Yet, when the circle of Christian fellowship was finally broken for the afternoon, it was dispersed with a prayer for ‘every soul in the city–the kind masters, the faithful servants, and all those in between,’ and with an admonition to ‘give Caesar his due.’

It may be a fool’s errand to apply the rigors of reason to a creature of passion like Papa Will, yet I am reminded at length of another passage from the book of Matthew. That is, ‘to beware of false prophets, who come to you in the clothing of sheep, but inwardly are ravening wolves.’ The Evangelist tells us that we should be able to discern the false prophet from the true by the nature of their works; that it is ‘by their fruit [we] should know them.’ If it remains to be seen whether the fruit borne by Seymour’s ministry will be wholesome or bitter, St. Matthew’s prescription for the tree that bears bitter fruit is quite clear: ‘[it] shall be cut down, and shall be cast into the fire.’

In the words of Papa Will, ‘Amen.”

—George Washington Cable, “A Prophet in Darkest Congo,” New Orleans Picayune, August 13th, 1899.

[1] Short for Doctor Corbeau, e.g., 'Doctor Crow.'

[2] Scuttlebutt, gossip. The proverbial 'word' on the street.

“Although the Alaska Purchase of 1866 is traditionally considered to be the beginning of the long period of Russo-American cooperation, this is something of a post hoc fallacy. In truth, the speedy acquisition of Alaska owed as much to President Seymour’s four and a half years as Minister to Russia from 1853-58–and the Russian desire to realize some gain on a colony the Tsar rightly regarded as undefendable–as it did to any grand design on the part of Seymour. In trying to craft a series of historical events as a cohesive narrative, some of the most respected deans of the academy, such as Nevins and Dunning, have presented scholars and students with an account implying that the military and economic cooperation between the two powers in the late 19th century was an inevitability, with the cornerstones laid in the earliest days of the Second Republic. In fact, the Anglo-American tensions that boiled over in the 1870s were only simmering during Seymour’s term, and said tensions were the main driver of the later Russo-American alignment. While it is accurate to consider the Seymour years as ones in which the Jacksonian order was revised and expanded to accommodate the new political reality in the post-secession United States, Seymour the individual had as many Jeffersonian inclinations as he did Jacksonian ones. Thus, even if his foreign policy outlook was generally anti-British, it was also generally isolationist. In the Alaska Purchase, Seymour saw echoes of the Louisiana Purchase. In the liberalization of trade with the Russian Empire, Seymour saw an opportunity to satiate his appetite for free trade at little political cost. Taxed or untaxed, aside from some luxury goods, vodka, and assorted exotic furs, there were very few goods in the market that the Russian Empire could provide which could not be obtained more cheaply domestically.

By way of counterargument, it could just as easily be said that it was Seymour’s 1870 death that truly created the environment for Russo-American alignment in the following decades. Although the administrations of Seymour and Logan are often treated as a unit, there were important differences in the approaches of the two men. Logan was a western back-slapper, well attuned to the yawp and graft of nineteenth century politics. Seymour was a well mannered New England WASP, nominated for the Vice Presidency in 1864 because he represented one of the most respectable and articulate voices among the Peace Democrats. Whereas eastern bluebloods had been somewhat overrepresented in Seymour’s cabinet, upon his accession to the presidency, Logan immediately set about changing the makeup of the cabinet to cater to various important Democratic constituencies. Although three easterners–Griswold, McLane, and Parker–were all retained in their cabinet posts, they were all supremely well qualified, and in the case of Parker, an important national spokesman of the Democratic center with connections to the urban machines of the Northeast. At Post, Baltimore power-broker Joshua Van Sant was replaced by Governor John Phelps of Missouri, a key ally of Julian League figurehead Frank Blair, Jr., and at Treasury, the Connecticut-born New York magnate Erastus Corning was pushed out in favor of Congressman George Pendleton, an Ohio populist and Greenbacker. Most important for the purposes of the Anglo-American conflict was the replacement of Alpheus Williams as Secretary of War in favor of California Senator James Shields. Although Williams was a Michigander by adoption, he was Connecticut born and bred, a graduate of Yale Law who had come by his wealth through inheritance–a Democrat in the mold of Seymour, in other words. Shields, on the other hand, was a self-made banty rooster of an Irishman who was notable for having dealt Stonewall Jackson a rare defeat during the War of Secession and for having deep connections with the Irish diaspora around the country. Although Shields himself publicly denounced the ‘secret character’ of the Fenian Brotherhood, he was a lifelong Irish patriot who promoted many officers with Fenian sympathies and even Fenian allegiances, and thousands of surplus war rifles infamously found their way into the hands of the Brotherhood during his tenure…

Though the resentments which fueled the Anglo-American Crisis had been building since the War of Secession and the Montreal Conference, the proximate cause–the Fenian campaign of terror and insurrection–is clear. The first Canadian raid, undertaken in September of 1870, not only damaged the Welland Canal and resulted in the sacking of Fort Erie, it also turned former US General Michael Corcoran, the military chief of the Fenian Brotherhood, into an American celebrity and an international fugitive…

In a series of events which echoed the Trent affair ten years before, Corcoran, who had been in hiding since the raid, was captured by the HMS Danae while en route to Havana on board the SS Jerusalem, an American-flagged merchant vessel. If the American press was predictably outraged by the high-handedness of the interdiction, the American government was thrown off-balance by the dilemma. Corcoran was a fugitive from American justice just as he was a fugitive from Her Majesty's, and his fugitive status had been useful to the administration specifically and the Democratic Party generally. With Corcoran in the wind (and with little effort being made to find him), the urban ward heelers and bosses of the party could raise toasts in his honor in the public houses and saloons without ever having to defend such sentiments in the parlors of the uptown gentry. When Corcoran was captured, it made this sort of widespread prevarication impossible and narrowed Logan's options considerably. If he was too conciliatory towards the British, he would lose the Irish, who had become, since the departure of the South ten years before, arguably the most powerful faction in the Democratic Party. Yet Logan could not give in to that faction’s most sought after demand–a pardon for Corcoran–without losing broader respectability. While it was one thing to look the other way when Corcoran breezed through the Irish wards of Philadelphia or Boston to pass the hat, it was quite another to demand his extradition from the United Kingdom and, having secured it, fail to prosecute him. So Logan took the only options he felt he had. First, he demanded an apology and a reparation of $5,000 for the interdiction of the Jerusalem. Second, he demanded the extradition of Corcoran so he could face trial in the US for his violation of the Neutrality Acts. Logan's British counterpart, the aging Lord Russell, refused. To boot, he made counter-demands of £50,000 for the damages to Fort Erie, and (at the behest of Gladstone) that the US agree to sit for a round of arbitration to determine the size of the US indemnity for damages to the Welland Canal. The American press howled with outrage and Fleet Street murmured with tongue-in-cheek approval. When Logan responded by urging the Senate to abrogate the Rush-Bagot Treaty of 1818, which had demilitarized the Great Lakes, the roles were reversed. The London broadsheets huffed in indignation; the New York press roared in approval.

Relations only deteriorated when a coalition of Democrats and Radicals in the Senate obliged Logan and abrogated the Treaty in May of 1871. In July, what had been simmering began to boil over when Corcoran was sprung from Her Majesty's Prison in St. John’s, Newfoundland. In a stunning turn of events, Corcoran turned himself in to US authorities at the Port of New York a week later. This was both a calculated gesture to influence public opinion in the US and Ireland, while also being an exceedingly favorable jurisdiction in which to impanel a jury…

…Corcoran’s gambit paid off when he was acquitted in early October. Though the jury's decision divided opinion even in New York,* it utterly inflamed it in the United Kingdom…

Benjamin Disraeli, having finally captured the premiership after many years in opposition, made the perfunctory demand for the re-extradition of Corcoran when news of the ‘monstrous verdict’ came down. When this request was denied, the Crown gave the Americans notice to vacate the Court of St. James and British diplomats were recalled from Washington, DC. For the remainder of the Crisis, communication between the two powers was done through a mix of Confederate, French and Russian intermediaries and by the Richmond diplomatic corps of both nations…

During the Winter and Spring of 1872, as Congress debated the size and scope of the naval rearmament and a new tariff regime against the British, the American press began to wonder at the true meaning of the words ‘Manifest Destiny,’ and their answers were rarely satisfactory to British ears. From San Francisco (home of the Giant Powder Co.) to Boston (ever so close to the Springfield Armory), the Fenian Brotherhood raised money for the cause while Corcoran and Sweeney plotted their next move. On Easter Monday of 1872, their plans came to fruition when a series of dynamite bombs were set off across the Canadian Great Lakes. The two most spectacular events were the early morning bombings that sank the HMS Britomart and mortally wounded the Cherub, but significant damage was also done to the docks in Goderich, Toronto, and Kingston in separate bombings later that day…"

— David W. Blight, A Hue and Cry From All Corners: The Painful Birth of the Second Republic, 1865-1876 (New York: Scribner, 2001) 278-284.

* The front page of The New York Times on October 3rd, for instance, bore the single word ‘HUMBUG’ emblazoned below the masthead. Compare this to ‘AN INNOCENT MAN’ from The New York Daily News and the ‘LUCK O’ THE IRISH?’ from The New York World on the same day.

“ Oh! Come off it, Porter. Who could forget a thing like that? Wasn’t that the point?

Morning of New Year’s Day, 1900. First damned day of the twentieth century, and the news was already all over the city. We were over on Desire, and we found out from the Aronsons and the Maestris– the neighbors that lived on either side of us–we found out from them first thing that morning. Now, at the time, I was reading the law at Tulane and Benjamin, and all of us at the law school, we all ‘knew’ Papa Will would be arrested for incitement sooner or later. The swells and the high-sniffers in my class–the mazhory, my mother would have called them–they were all taking bets on when it would happen. And the handful of us there with Parsonist sympathies, we fantasized about who might defend him and on what grounds. He was a free man, after all, and a free man’s got a right to his religion, even a Negro. That’s what the law says, doesn’t it?

I should have known something was in the works when the odds for an arrest dropped right before the holiday break. The odds for the rest of December dropped off a cliff, but the odds for January dropped too. I chalked it up to the season–Chanukkah, Christmas, New Year’s, Epiphany. December and January are not the best times to get things done in New Orleans, is what I’m saying. Now, was I naïve? Of course I was naïve, I was all of twenty! We were all naïve…

The ‘Immolation of Doctor Corbeau,’ they like to call it. You can always trust a swell to put lipstick on a pig, you know it? But they burned him alive, is what they did. Nothing but a common lynching. It’s not high-tone because it was a mob of young masters from the Krewe of Comus. A drunken mob is a drunken mob. If you’re the man getting burned alive, it’s the torch what gets your attention, not the cufflinks of the fellow that’s holding it…

Yeah, yeah...I know what was said, alright? I know the rumors. Drunken revelry got out of hand? High-spirited boys and all that? As far as I can tell, all of those legends come from that letter in The Item. Now, I’ll grant that that letter was a confession of sorts, but it was still nothing but lies. There was nothing spontaneous about what happened that night. Hey, if it was spontaneous, then why did the odds for an arrest go so long for December and January? Right? And listen here, if you can get any of the mendacious devils who was at T and B back then to talk to you and tell you the truth, anyone can corroborate that…

But nobody–not nobody on the street anyway–nobody believed the story that ran in the papers. Even if the news about the odds hadn’t leaked–and it did–the people would have found out anyhow… For one, the Turks[1] in general, and especially the young Turks, can’t do a damned thing without their Negroes, and it was even worse back then. That New Year’s Eve, the same body servants who had dressed and fed their masters morning, noon, and night for years and years–they were given the evening off on one of the city’s biggest social occasions. And the young Turks, for the record here, thought this was the height of espionage. They were so convinced--even after Smalls and all the rest--in the dullness of Negroes that they expected a night off and a jug of whiskey to cool suspicion. Well, of course it did the opposite…

…and not only do the Turks love to gamble, they’re conditioned and disposed to be lazy. This was even truer then than it is now. So you’ve got rich, lazy young men with a penchant for fine brothels and games of chance–of course they had connections to the Honorab! Hell, most of them are probably kin to an Honorab [2] somewhere down the line, and some of the plotters made an inquiry or two about a paid assassination in the weeks before the lynching. But the Honorab wouldn’t do it, and after St. Vincent’s Day, they weren’t shy about putting the word out…

It only took about a week for all this to become common knowledge in the tenements. By the next Saturday, when the gentiles gathered for the Epiphany, that was when a lot of people put it all together–especially the slaves, who didn’t get to socialize as regular as everyone else...

It started with a vigil in Congo Square–or at least an attempt at one. On Siringo’s orders, the Metropolitan Police had kept the Square closed since the lynching. Now, there was a lot of Cubans and even some Sicilians in Papa Will’s congregation–they try to play that down these days, but it’s true–and they didn’t take the news about the Square so bad. But the Negroes were a different story. For the Negroes, Congo Square was like City Hall, church, and the fairgrounds all rolled into one. It was where they worshiped, where they socialized, where they bought and sold things. They’d been going there for more than a century. Slave or free, they considered that they had a right to it, and they didn’t take to the idea that they would be denied access to it on account of some Uptown white boys’ crimes.

So that Sunday was the feast day of St. Agnes. In the Catholic tradition, Agnes was a martyr that the Romans unsuccessfully tried to burn alive–supposedly, her pyre wouldn’t catch, and some Roman had to give her the chop instead. Seems to me, it’s a pretty weak miracle, but what do I know, right? Anyway, the sermons that week touched a nerve when several of the parish priests used the legend of St. Agnes to demonstrate, by way of example, that Papa Will wasn’t a real holy man.

To say the least, this was not a well-received message.

So after church that Sunday, several groups of Negroes gathered at the entrance to the Square, demanding to be let in. They wanted to mourn together. Now, the smart thing from the cop’s point of view would have been to let them pass, then show up with reinforcements and eject them. They were outnumbered, maybe ten to one, twenty to one, and they were giving the orders, but the crowds weren’t dispersing. But since cops are cops, they did the stupid thing instead of the smart thing. One of them–a lot of folks say it was Brennan, the fellow that got killed, but who knows really–he clapped a boy over the head with his stinger. Split his scalp wide open. Then everything descended into chaos. Somebody got a hold of one of the policeman’s guns and Brennan ended up with an extra hole in his head. Five Negroes, I think, got killed in that initial melee–one of them was an old woman, I remember–but the police were overwhelmed. Run off the god-damned street.

They had to skedaddle back to their hole in the Quarter…

Of course, the cops acted like this was the second coming of Robert Smalls and Bass Reeves all rolled into one, and they sent up the hue and cry. But as far as containing the crowd, the genie was out of the bottle. The Square’s too much in the center of the city, so they opted to try and cordon them off. Of course, they botched that too. On some sides of the cordon, they gave the crowd too much space, on the other sides, it was too little. When they tried to tighten it up, it was a disaster. The cops coming in from the Parish Prison broke out into a pogrom, and the ones coming in from the direction of Canal got their asses kicked by the rioters. Fighting continued off and on all that evening and into the night. And by the way, the Honorab got quick revenge for the pogrom. Five officers turned up dead by that morning. All five were garroted–that’s as sure a sign as any–but there were no witnesses to any of the killings. Then there was another dozen that turned up the same way between then and Mardi Gras. That’s one of the bits that gets lost in the retellings, with everything that came after…

Of course, all this wasn’t happening in a vacuum. As soon as things started to get out of hand, Charlie Siringo was on the phone with the Governor, putting a bug up his ass to send out the militia, and wouldn’t you know it, they were out on the street by the next morning. And that’s why you got the result that you got. The St. Vincent’s Day Massacre–it’s a story that’s been told a thousand times, but you don’t get ninety-nine martyrs in Congo Square without General Lewis and the state militia. The police didn’t have the firepower or the discipline, but Siringo worked on the Governor, and when General Lewis arrived, the Chief of Police whipped him into a frenzy. Well, you know the militia had all the firepower in the world…

There were a couple dozen executions afterward, and about a thousand people were sold to Forrest & Son. I suppose they thought that would solve the problem, but the Turks never learn…

Well it did change my life, Porter. I was almost a lawyer. I used to have faith in those things. But lawyering, you know, it would have done no good. What good was the law if a free man engaged in fasting and prayer by the lakeside could be burned alive by a mob with no consequence to the perpetrators? What good was the law if a troop of drunken policemen could loot a neighborhood without even a reprimand being issued? What good was the law if the state militia could come in and mow down a congregation of mourners at the corner of Canal and Rampart? The law is for reasonable times and reasonable people.

You can’t reason with the Turks, Porter. The only thing they understand is bullets and whips.”

—Lew Davidson Bronstein, 1922, recorded by William Sidney Porter; First published in Winston Groom, Even if it Killed Him: The Last Assignment of William Sidney Porter (Norfolk: Fortune, 1972) 331-340, Appendix A.

[1] A term of derision for wealthy Southern slaveowners originating in the Russian-Jewish communities of New Orleans, connoting decadence and cruelty. Adopted throughout the urban South by the early 20th c, especially by Parsonists and other leftists.

[2] Les Honorables, an organized criminal group of free persons of color originating in New Orleans, sometimes called the 'Mullatto Mafia' in the United States. As almost all of Les Honorables were of mixed racial heritage and typically hailed from south Louisiana, (strained) kin relationships between upper-class whites were not unheard of.

"Upon the mountain when my God spoke,

out of God’s mouth came fire and smoke.

All around me, it looked so fine,

I asked my Lord if all was mine."

---Traditional, "Every Time I Feel the Spirit," quoted in Moe Asch, Voices of Discontent. (New Orleans: Free University Press, 1951.)