You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Miranda's Dream. ¡Por una Latino América fuerte!.- A Gran Colombia TL

- Thread starter Red_Galiray

- Start date

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Threadmarks

View all 76 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 62: The Balkan War Chapter 63: The Liberal Revolution Appendix: The Colombian National Army Appendix: The Colombian Cavalry Appendix: The Colombian Artillery Appendix: The Colombian Navy Chapter 64: From the Andes to the Caribbean Chapter 65: The Irrepressible ConflictYes. I will continue it some day and finish it no matter what. It's just that I've been really busy with school and my personal life, and, well, I have prioritized somewhat my other TL, which is far more popular. But I'll come back and continue this one too. It's dear to my heart.Are you planning on continuing this timeline? It's so very interesting.

Voting for this year's turtledoves has started and, although Miranda's Dream was not nominated, my other TL, Until Every Drop of Blood is paid, was. If you've read it you may consider voting for it this year. It's really similar to this work (after all, I'm the author of both) and in some ways I consider it superior (the first chapters of this TL, I think, are too short and devoid of details). Even if you don't vote for it, then it's still worth it to check it out!

2021 Turtledoves - Best Colonialism & Revolutions Timeline Poll

The Revenge of the Crown : An Alternate 1812 and Beyond; @Sārthākā A New World Wreathed in Freedom - An Argentine Revolution TL; @minifidel The Last Hanover: The Life and Reign of Queen Charlotte; @The_Most_Happy The Glowing Dream: A History of Socialist America; @Iggies Imperator Francorum...

www.alternatehistory.com

Man, I do miss this Timeline. I check every now and then, hoping @Red_Galiray has posted something new and AH just forgot to tell me.

Dude, don’t do this. Red_Galiray doesn’t like it when posters do that.Man, I do miss this Timeline. I check every now and then, hoping @Red_Galiray has posted something new and AH just forgot to tell me.

Last edited:

Your comment inspired me to finally write another chapter, Omar. I love this TL, but I must admit it's sometimes hard to muster enough will to write it since so few people read it. But your comment reminded me that that doesn't really matter. It's something special for me and for other people as well, so it's worth continuing even if it's not as popular as I'd like. It took me a while, but here's a new update after many months!Man, I do miss this Timeline. I check every now and then, hoping @Red_Galiray has posted something new and AH just forgot to tell me.

That's true, but there's a difference between "wheres the new chapter" and shows of support and appreciation that are not pushy like Omar's.Dude, don’t do this. Red_Galiray doesn’t like it when posters do that.

Chapter 65: The Irrepressible Conflict

The Compromise of 1857 maybe saved the Union for a few more years. Its flaws would become apparent in due time, and with the benefit of hindsight the great majority of politicians lambasted it as a “deal with the devil” that had just prolonged the life of the accursed institution. But at the time it was celebrated as a final settlement of the slavery question, and an end to all sectional strife. As the people drank and danced to celebrate the salvation of the Union, few could imagine that in truth the Compromise of 1857 had started its disintegration.

In some ways, the very sense of finality of the Compromise was one of its greatest weaknesses. No party, not the Administration’s Liberals, not the opposition’s Democrats, and less of all the “new ultras”, the Republicans, was satisfied with the Compromise in its final form. The admission of Texas and Sacramento as slave and free states respectively was not contested, and though it was a bitter pill, the Southerners accepted the repudiation of slave debts accrued during the war with Mexico and abolition in DC. Rather, the source of conflict laid in two measures, one due to its ambiguity, the other due to its decisiveness: the repudiation of the Missouri compromise and the Fugitive Slave Act.

The Fugitive Slave Act was one of the most contentious measures of the Compromise, despite the fact that it was, in some ways, the most legally justified of them all. The US Constitution, using its usual roundabout term of “persons held to service or labuor”, decreed that slaves that escaped to other areas of the United States wouldn’t “in Consequence of any Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour, but shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due”. The issue seemed quite clear – escaped slaves would remain slaves, and they should be returned to their owners. But the devil was in the details, and the vagueness of the Constitution regarding how it was to be enforced and by whom.

To put this Constitutional provision into effect, the Congress had enacted in 1793 a Fugitive Slave Act that allowed slaveholders to cross into another state, capture the people they enslaved, and bring them before any local or federal court to prove his ownership. The law’s lack of any protections for Black people, including no right to testify or habeas corpus “amounted to an invitation for kidnappers to seize free blacks” in Northern eyes. Indeed, many people were kidnapped and taken South, sometimes without the intervention of a magistrate as required by the law, sometimes with the intervention of apathetic judges who did not care if slave catchers had taken the right man. Perhaps the most famous and tragic example is that of Solomon Northup, a free man who lived years in slavery in Louisiana until the Mexican War gave him a chance to escape.

Solomon Northup's story became an icon within the anti-slavery press

Angered by the presence of slavecatchers on Northern soil and outraged by the abuses committed under the law, several Northern states enacted “personal liberty laws” that sought to give substantial protections to Northern blacks, including the right of testimony, trial by jury, and the right of habeas corpus. Slavecatchers could even be indicted for kidnapping, and even if the juries weren’t anti-slavery enough to convict, the result was often the escaped slave remaining in freedom. The Supreme Court was unable to settle the issue in the case of Prigg v. Pennsylvania, which resulted from the conviction of Edward Prigg as a kidnapper after he had taken a woman and her children, people who had escaped their enslavement by fleeing to Pennsylvania, back to Maryland. Prigg appealed all the way to the Supreme Court, which declared that “the obligation of enforcement of the fugitive-slave clause of the Constitution was essentially federal, and that the states need not devote their law-enforcing apparatus to this function.”

The supremacy of the federal government meant that most personal liberty laws were unconstitutional, insofar as they interfered with the federal government’s right and duty to secure slaveholders’ property. For that right to be respected, however, the Federal government would have to enact stronger measures, especially in the face of new personal liberty laws that sought to obstruct and limit as much as possible the capacity of slaveholders to re-enslave people under the terms of the 1793 law. For instance, states forbade their officials from cooperating with slaveholders or use their facilities, such as jails or courts. Deprived of the coercive power of the states, slaveholders looked towards the Federal government for the enforcement apparatus necessary. Thus, the demand for a new federal fugitive slave act grew.

The war with Mexico both stopped these efforts for a time and reinvigorated them afterwards. Pointing to the escape of thousands of slaves to the North or to the territories during the occupation of Louisiana by the Mexican Army, Southerners insisted on the enactment of a stronger fugitive slave act. In truth, the majority of the fugitives had fled to Mexican Texas (now known as Alamo), and had been settled there in small homesteads. Conscious that Marshal Salazar would never accede to returning them or paying any compensation, the American diplomats and later Southern politicians did not press the point. “Mr. Salazar, I’m afraid, would shoot me if I proposed such a plan”, reported the American ambassador. Instead, they focused their energies in the North, whose anti-slavery efforts seemed more egregious because they were countrymen instead of enemies.

Southerners obtained their prize in the Compromise of 1857, which “seemed to ride roughshod over the prerogatives of northern states” by creating federal commissioners that would decide whether the kidnapped person was to be remanded to slavery, and by empowering federal marshals and deputies to aid slaveholders. The law allowed marshals to deputize citizens on the spot, and imposed steep fines and criminal penalties on marshals that refused to help and people who tried to help the fugitives. Most outrageous, the law gave blacks no power to proof their freedom by keeping them from testifying, bringing witnesses, being trailed by juries or invoke the right of habeas corpus. The fact that commissioners would receive 5 dollars if the fugitive was declared free and 10 if they were remanded to slavery, though “supposedly justified by the paper work needed”, served in practice as a “bribe” that stacked the odds against blacks even more.

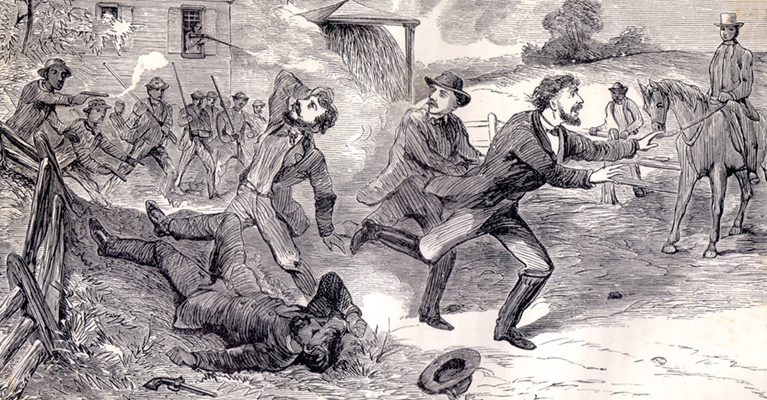

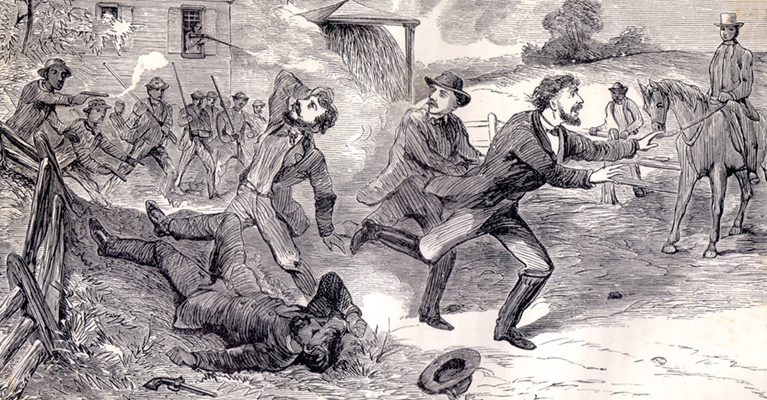

The Fugitive Slave Act inspired great resistance in Northern communities

The Fugitive Slave Act was, in the view of a Southern politician “the only measure of the Compromise calculated to secure the rights of the South”. Indeed, while abolition in D.C. was a bitter pill to swallow, the state admissions were more of a draw, and the repeal of the Missouri Compromise merely started a more vicious struggle, the Fugitive Slave Act seemed a complete victory over of Southern rights over the abolitionists. In practice, the act was not very consequential since, after an initial flurry of dramatic persecutions, it was rarely invoked. In any case the number of slaves who managed to escape was minuscule when compared with the millions that remained in bondage. This was especially egregious in the view that the region that clamored for a Fugitive Slave Act with the loudest voice was the Deep South, an area few slaves were ever able to escape from.

Rather, what the South sought to protect was their honor, demanding the act as a matter of principle rather than out of practicality. “Although the loss of property is felt,” Senator Mason of Virginia said for instance, “the loss of honor is felt still more.” The measure was also calculated to strike against the underground railroad, a legendary but loose organization that helped and sheltered the people who escaped their enslavement. “Magnified by southerners into an enormous Yankee network of lawbreakers who stole thousands of slaves each year”, the underground railroad in truth only helped a couple of hundred of enslaved people, at most, the great majority of them coming from the Upper South. It must be pointed out, as David Potter does, that the abolitionists that seldom risked a great deal were also the most lionized by the achievements of the underground railroad, “which draws attention away from the heroism of the fugitives themselves, who often staked their lives against incredible odds, with nothing to aid them but their own nerve and the North Star”. “If anyone helped them”, Porter continues, “the evidence indicates that it was more likely to be another Negro, slave or free, who chose to take heavy risks, than a benevolent abolitionist with secret passages, sliding panels, and other stage properties of organized escape.”

Nonetheless, the very existence of the underground railroad and the personal liberty laws were offensive to the Southerners, who saw in them nullification of the Constitution and a persistent refusal to recognize their right to enslave people. The Fugitive Slave Act was seen as a way to remedy this problem, and as long as the North acquiesced and respected it, its finality, and thus that of the Compromise, could be maintained and further discord avoided. Naturally, this didn’t happen. Though the law was enacted by a thin margin by the combined votes of Democrats and pro-administration Liberals, the anti-slavery Liberals, most of whom would desert the party in favor of the new Republican organization, resisted it to the very end. Even after it had been signed into law by President Scott, the Republicans, and a large section of Liberals, saw in it a “covenant with the devil” that had turned the Federal government into a “dirty slavecatcher”.

Again, it was the principle of the law rather than its practical effect that arose the most bitter resistance to it. By protecting slavery to such an extent all over the United States, the law seemed to embrace the “slavery national” Southern doctrine that was fundamentally opposed to the “freedom national” interpretation of the Constitution as anti-slavery in a round-about way. The Fugitive Slave Act, said Senator Seward in a speech that was derided as “monstrous and diabolical”, was a compromise with “an unjust, backward, dying institution” that attempted to “roll back the tide of social progress”. Such a concession to slavery would prevent it from dying “under the steady, peaceful action of moral, social, and political causes, . . . and with compensation”. If slavery was maintained, “the Union shall be dissolved and civil war ensue, bringing on violent but complete and immediate emancipation.” It was, in total, a horrendous law that went against liberty and human rights, and even if it was constitutional “there is a higher law than the Constitution”.

The Higher Law doctrine contributed to the Republicans’ refusal to recognize the Compromise of 1857 as a final settlement of sectional disputes. Republicans could simply not accept it, and instead sought to resist it by all means necessary. Not only did Republicans file suits trying to get the Supreme Court to declare the Fugitive Slave Act unconstitutional, but new personal liberty laws were enacted in several Northern states and Republican congressmen attempted in vain to obtain the repeal of the law. Charles Sumner introduced no less than twenty motions to that effect, forcing Southerners and moderates to enact a new gag rule even though Sumner’s motions never came close to a majority. But they did command unanimity among the Republicans and even sometimes obtained a few Liberal defectors.

The anti-slavery aptitudes of Northerners helped give strenght to the Republican Party

Far more enraging for the South was the violent resistance to the act carried by several Northern communities. Mobs of African Americans and White abolitionists had been repealing slavecatchers for decades already, but the Fugitive Slave Act embittered the fight and gave it a new national significance. Fiery abolitionists like Wendell Philipps declared that they had to trample the law under their feet – “it is to be denounced, resisted, disobeyed”, said a Boston anti-slavery society, because “as moral and religious men, we cannot obey an immoral and irreligious statute”. Consequently, local anti-slavery societies and many biracial communities formed vigilance committees that warned Blacks against kidnappers and threatened slavecatchers. This led to many dramatic scenes throughout the North, though the “cockpit of the new revolution” remained in the cockpit of the old one – Boston.

One of the most “dramatic flights” was that of William and Ellen Craft, a black couple whose escape from Georgia “had become celebrated in the antislavery press”. Their former owner had come to Boston to try and re-enslave them, vowing to capture them even “if we have to stay here to all eternity, and if there are not men enough in Massachusetts to take them, we will bring them some from the South”. Theodore Parker, a local clergyman, was decided to prevent this. Parker guarded the Crafts in his house, where he kept a “veritable arsenal” alongside the revolver he always carried. The enraged slaveholder tried to break into Parker’s house with the help of the Federal marshals and some men he had brought from the South, which started a riot that ended with him and other man dead. By the time that troops had restored order, the Crafts were already in a ship to England.

The strong Southern backlash forced President Scott to extent his aid, offering “all the means which the Constitution and Congress have placed at his disposal” to enforce the law. Scott did not do this out of love for slavery. Indeed, Old Fuss and Feathers was naturally anti-slavery, but he believed his major obligation was the maintenance of the Union, which necessitated the maintenance of the Compromise. But the Bostoners remained defiant. “I would rather lie all my life in jail, and starve there, than refuse to protect one of these parishioners of mine,” Parker told Scott. “You cannot think that I am to stand by and see my own church carried off to slavery and do nothing.” The Craft drama was repeated when a mob liberated a black man named Shadrach “out of his burning, fiery furnace” by overwhelming the Federal marshals that had captured him and sending him to Canada. “I think it is the most noble deed done in Boston since the destruction of the tea in 1773”, exulted Parker.

Attempts to enforce the penalties of the law failed as well, as Boston juries refused to convict any men who had taken part in these riots or aided fugitive slaves. “Massachusetts Safe Yet! The Higher Law Still Respected,” celebrated anti-slavery journals, while conservative newspapers and Southerners denounced “the triumph of mob law” and how Boston had been “disgraced by the lowest, the meanest, the blackest kind of nullification”. Especially humiliating was the failure of the Scott administration to punish those who nullified the law, and soon enough the South threatened secession again: “unless the abolitionist rioters are hung . . . WE LEAVE YOU! . . . If you fail in this simple act of justice, THE BONDS WILL BE DISSOLVED.” Violent acts that often resulted in the death of slavecatchers and the liberation of fugitives took place in many Northern communities aside from Boston, such as Syracuse or Christiana.

The Scott administration found it hard to enforce the Fugitive Slave Act. Not only did Northern juries and judges refuse to cooperate, resulting in the complete exoneration of those who had taken part in these rescues, but trying to bring down the force of the government only made martyrs out of the abolitionists and increased sympathy for their cause. Already reviled for their Compromise with the Slave Power, the Administration found that the enforcement of the act only resulted in losing strength within the North, something they could not afford when the Liberal Party was already dead in the South due to its support for peace during the war. Moreover, at the same time that these daring efforts for freedom were taking place, Southern filibusterers were attacking Cuba and Central America, and Scott’s failure to stop them proved to be more embarrassing. If Scott brought all his powers against the abolitionists but failed to do so against the filibusterers that would be irrefutable proof of his alliance with the Slave Power – and also a foreign policy disaster for the filibuster expeditions had alienated Mexico, Colombia and Britain.

Slavecatchers were violently driven away

Northern resistance to the act should not be overstated. Of hundreds of re-enslaved people, Northern communities only rescued a handful. “The law was defied primarily by spiriting slaves away before officers found them, rather than by resisting officers directly”, and indeed, after the first couple of years the number of escapees captured dropped sharply because most off the vulnerable had fled to Canada (Toronto’s Black population doubled). The commercial elites of the North, the hated “Lords of the Loom” who had supported the Compromise with the “Lords of the Lash” in order to assure stability and continued commerce, extended their hearty support, not out of love for slavery itself but in an attempt to prevent Civil War. Declarations that the law was enforced without troubled everywhere but Boston failed to conciliate the South, however, for the slavocrats were increasingly convinced that the North would not respect the Compromise and could not be trusted to respect Southern rights. In that case, the only answer was secession. At the same time, the Republican party was gaining strength as the only way to prevent the complete victory of the slave power. Far from settling the controversy, the Compromise had only created a far more bitter sectional and partisan struggle.

Proof of that were the 1857 midterms, which took place later in the year the Compromise was passed and which showed that the Republican revolt was not a mere brief-lived tantrum, but a complete political realignment. Throughout the North, Democrats and the Liberals were defeated in bruising contests where they were portrayed as pawns of the Slave Power. Similarly, to how the Liberals had for all purposes ceased to exist in the South, the Democrats organization was already in the throes of death, all its members reviled due to their support for war for slavery that had taken so many sons, husbands and brothers. The Fugitive Slave Act, the filibuster expeditions and events in Nebraska helped seal their fate, and the Democracy was basically exterminated.

If Democrats were blamed for the Slave Power’s measures, Liberals were blamed for falling to stop them. The Liberal ruin wasn’t complete, but many Liberals went down in defeat. Only in the “Lower North” areas of Ohio, Illinois and Indiana did Liberals hold, elected by moderates who didn’t like slavery but didn’t like abolitionism either. In most of the North the Republicans swept to victory, showing a decisive repudiation of the Compromise and the growth of anti-slavery sentiments. The defeat was a severe blow to the administration, which believed that it could count on moderate Northerners to show Yankee commitment to the Union and Compromise. It was also a strong hit against Southern faith in the Union for it showed that the North had not accepted the Compromise after all.

Instead of forcing the administration to grow closer to the South, the midterms forced it closer with the Republicans, who were willing to back and support Scott if he showed “that he could emancipate himself from the Slave Power”. The South, meanwhile, elected a “motley throng” of fire-eaters and secessionists that were bitterly opposed to the administration and the North. Compromise with them was impossible unless Scott accepted measures that would destroy him and what remained of the Liberals in the North. Wishing to hold into power, and be reelected in 1861, as the only way to stave off conflict by preventing a pro-slavery Southerner from being elected, Scott and the Republicans became closer. No formal agreement was made, but a tentative coalition between Liberals and Republicans that could control the House was being envisioned as a counter to the still Democratic Senate. Such a counter would be needed when Southerners, both federal and state, started to push for making a new slave state out of Nebraska.

An obvious antipathy to the Compromise was evident throughout the North

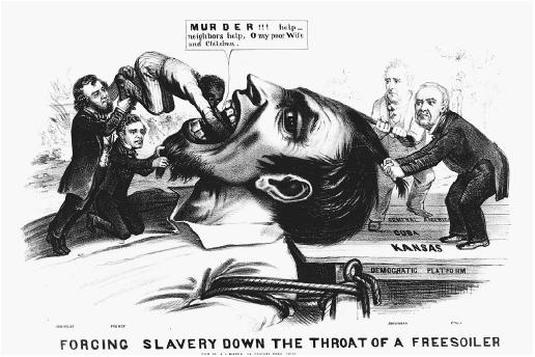

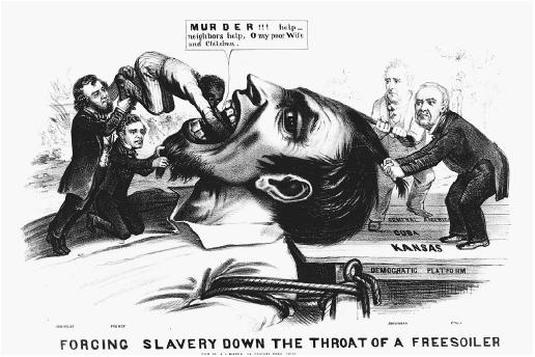

The Compromise of 1857 included a measure that repealed the Missouri Compromise, made decades ago, allowing Southerners to enter the territories with their slaves. This was of the utmost necessity for the South, because otherwise those territories would inevitably turn into free states that would presumably vote for anti-slavery measures. The fact that the war had been ended early due to Northern wickedness, at least in Southern eyes, made the need more pressing, because otherwise it meant that the primarily Southern Army had sacrificed so much for territories that would be closed to them. However, the Missouri Compromise had long been regarded as “a sacred covenant sanctified by decades of national life”, whose repeal could raise a “hell of a storm” that would make “even the bloody battles in Louisiana and Veracruz look like a gentle shower.” Like the Fugitive Slave Act, the repeal was passed by thin margins. But Northerners were decided to resist it, this time with more energy because there was a clear goal: keeping the slavocrats out of Nebraska and making it a free state.

“Since there is no escaping your challenge”, declared Seward, doubtlessly after recouping some of the Higher Law fire, “I accept it in behalf of the cause of freedom. We will engage in competition for the virgin soil of Nebraska, and God give the victory to the side which is stronger in numbers as it is in right.” The fact that Seward, who had supported compromise and was the Administration’s spokesman, was the one throwing down the gauntlet is significant, for it shows that repudiation of the repeal was strong even among moderate men, and that the President and his circle didn’t wish for new slave states to be accepted. In the South, this smacked of betrayal, for Southerners had understood that the repeal of the Compromise would guarantee the creation of new slave states that would “join their sisters in the protection of our holy institutions”. If the administration and Northerners fought to keep the territories free, then there was no substantial difference and the Compromise was worthless. But the slavocrats would not give up easily, and what could not be enacted by law could be enacted by blood.

Northerners, aided by Emigrant Societies funded by and coordinated from New England, poured into Nebraska at the same time as Missourians and other Southerners, together with their slaves, did. “The game must be played boldly”, Senator Atchison declared. “We will be compelled to shoot, burn and hang, but the thing will soon be over. We intend to ‘Mormonize’ the Abolitionists.” Groups of “ank, unshaven, unwashed, hard-drinking Missourians”, fueled by their hate for "those long-faced, sanctimonious Yankees" and their "sickly sycophantic love for the nigger”, poured into the enormous territory with the full intent of driving all Free-Soilers out and secure it for slavery.

The territorial governor, a certain Nathan S. Faulkner, a veteran of the Mexican-American War, was not about to accept these illegal efforts. Though certainly not a fiery abolitionist, Faulkner had no love for the institution either, and the use of violence and fraud by the “Border Ruffians” drew him closer to the Free-Soilers. The declarations of prominent Border Ruffians didn’t help matters: "Mark every scoundrel among you that is the least tainted with free-soilism, or abolitionism, and exterminate him . . . Enter every election district . . . and vote at the point of a Bowie knife or revolver!" The first task was to divide the enormous Nebraska into more manageable territories – indeed, the fact that the territory was so enormous was intentional, for it was hoped that would delay a fight and could lead to two different states being settled, preserving sectional balance. But Southerners wanted all or nothing, and they voted for the creation of a big state that would take most of the border with Missouri.

Faulkner, with the tacit blessing of the Scott administration, repudiated these proceedings. Aside from intimidation and ballot stuffing, the territorial governor cracked down on the violence that had started to cover the territory with blood. Soon enough, Free-Soilers, now known as Jayhawkers, started to fight tense and bloody battles against Border Ruffians all over Nebraska, though the most bitter fight was in the area of settlement near the Missouri border. There, Atchison led a band of Border Ruffians that attacked the Free-Soil capital at Lawrence, named after one of the Emigration Aid Society’s benefactors. The result was a pitched and bloody fight, that saw many buildings sacked and bombarded. Faulkner attempted to rally the Federal troops at his disposal to put it down, but to his horror he found that many were Southern veterans that saw in Nebraska a just price for their sacrifice. Instead, Faulkner had to rely on Northern veterans that still seethed at how the Slave Power had forced them to fight the war. The groups divided and the fight only grew bloodier and more intense.

The Battle of Lawrence

By the time the dust settled, it did so over more than 300 dead men and a completely destroyed town. Faulkner had been badly wounded, but he would survive, unlike Atchison, who fell in battle. News of the “Battle of Lawrence”, alternatively called the Lawrence Massacre, spread quickly. Southerners were horrified at how an administration officer had massacred the “innocent” Southerners that just wanted the government to honor their rights. Northerners hailed Faulkner’s defense of Lawrence, and cried against the Slave Power that had started that fight. A second battle started in Congress, that saw a Yankee congressman shot and a Southern one stabbed. Acts of political violence like that started to happen more often throughout the Union, and Nebraska continued bleeding. It was clear that the Union was tottering to its destruction, but on which terms that would happen was to be determined by the results of the next presidential election, which would take place in just a year. Still, as Southerners and Northerners armed and prepared for conflict, it did not take a prophet to see that Civil War was imminent.

In some ways, the very sense of finality of the Compromise was one of its greatest weaknesses. No party, not the Administration’s Liberals, not the opposition’s Democrats, and less of all the “new ultras”, the Republicans, was satisfied with the Compromise in its final form. The admission of Texas and Sacramento as slave and free states respectively was not contested, and though it was a bitter pill, the Southerners accepted the repudiation of slave debts accrued during the war with Mexico and abolition in DC. Rather, the source of conflict laid in two measures, one due to its ambiguity, the other due to its decisiveness: the repudiation of the Missouri compromise and the Fugitive Slave Act.

The Fugitive Slave Act was one of the most contentious measures of the Compromise, despite the fact that it was, in some ways, the most legally justified of them all. The US Constitution, using its usual roundabout term of “persons held to service or labuor”, decreed that slaves that escaped to other areas of the United States wouldn’t “in Consequence of any Law or Regulation therein, be discharged from such Service or Labour, but shall be delivered up on Claim of the Party to whom such Service or Labour may be due”. The issue seemed quite clear – escaped slaves would remain slaves, and they should be returned to their owners. But the devil was in the details, and the vagueness of the Constitution regarding how it was to be enforced and by whom.

To put this Constitutional provision into effect, the Congress had enacted in 1793 a Fugitive Slave Act that allowed slaveholders to cross into another state, capture the people they enslaved, and bring them before any local or federal court to prove his ownership. The law’s lack of any protections for Black people, including no right to testify or habeas corpus “amounted to an invitation for kidnappers to seize free blacks” in Northern eyes. Indeed, many people were kidnapped and taken South, sometimes without the intervention of a magistrate as required by the law, sometimes with the intervention of apathetic judges who did not care if slave catchers had taken the right man. Perhaps the most famous and tragic example is that of Solomon Northup, a free man who lived years in slavery in Louisiana until the Mexican War gave him a chance to escape.

Solomon Northup's story became an icon within the anti-slavery press

Angered by the presence of slavecatchers on Northern soil and outraged by the abuses committed under the law, several Northern states enacted “personal liberty laws” that sought to give substantial protections to Northern blacks, including the right of testimony, trial by jury, and the right of habeas corpus. Slavecatchers could even be indicted for kidnapping, and even if the juries weren’t anti-slavery enough to convict, the result was often the escaped slave remaining in freedom. The Supreme Court was unable to settle the issue in the case of Prigg v. Pennsylvania, which resulted from the conviction of Edward Prigg as a kidnapper after he had taken a woman and her children, people who had escaped their enslavement by fleeing to Pennsylvania, back to Maryland. Prigg appealed all the way to the Supreme Court, which declared that “the obligation of enforcement of the fugitive-slave clause of the Constitution was essentially federal, and that the states need not devote their law-enforcing apparatus to this function.”

The supremacy of the federal government meant that most personal liberty laws were unconstitutional, insofar as they interfered with the federal government’s right and duty to secure slaveholders’ property. For that right to be respected, however, the Federal government would have to enact stronger measures, especially in the face of new personal liberty laws that sought to obstruct and limit as much as possible the capacity of slaveholders to re-enslave people under the terms of the 1793 law. For instance, states forbade their officials from cooperating with slaveholders or use their facilities, such as jails or courts. Deprived of the coercive power of the states, slaveholders looked towards the Federal government for the enforcement apparatus necessary. Thus, the demand for a new federal fugitive slave act grew.

The war with Mexico both stopped these efforts for a time and reinvigorated them afterwards. Pointing to the escape of thousands of slaves to the North or to the territories during the occupation of Louisiana by the Mexican Army, Southerners insisted on the enactment of a stronger fugitive slave act. In truth, the majority of the fugitives had fled to Mexican Texas (now known as Alamo), and had been settled there in small homesteads. Conscious that Marshal Salazar would never accede to returning them or paying any compensation, the American diplomats and later Southern politicians did not press the point. “Mr. Salazar, I’m afraid, would shoot me if I proposed such a plan”, reported the American ambassador. Instead, they focused their energies in the North, whose anti-slavery efforts seemed more egregious because they were countrymen instead of enemies.

Southerners obtained their prize in the Compromise of 1857, which “seemed to ride roughshod over the prerogatives of northern states” by creating federal commissioners that would decide whether the kidnapped person was to be remanded to slavery, and by empowering federal marshals and deputies to aid slaveholders. The law allowed marshals to deputize citizens on the spot, and imposed steep fines and criminal penalties on marshals that refused to help and people who tried to help the fugitives. Most outrageous, the law gave blacks no power to proof their freedom by keeping them from testifying, bringing witnesses, being trailed by juries or invoke the right of habeas corpus. The fact that commissioners would receive 5 dollars if the fugitive was declared free and 10 if they were remanded to slavery, though “supposedly justified by the paper work needed”, served in practice as a “bribe” that stacked the odds against blacks even more.

The Fugitive Slave Act inspired great resistance in Northern communities

The Fugitive Slave Act was, in the view of a Southern politician “the only measure of the Compromise calculated to secure the rights of the South”. Indeed, while abolition in D.C. was a bitter pill to swallow, the state admissions were more of a draw, and the repeal of the Missouri Compromise merely started a more vicious struggle, the Fugitive Slave Act seemed a complete victory over of Southern rights over the abolitionists. In practice, the act was not very consequential since, after an initial flurry of dramatic persecutions, it was rarely invoked. In any case the number of slaves who managed to escape was minuscule when compared with the millions that remained in bondage. This was especially egregious in the view that the region that clamored for a Fugitive Slave Act with the loudest voice was the Deep South, an area few slaves were ever able to escape from.

Rather, what the South sought to protect was their honor, demanding the act as a matter of principle rather than out of practicality. “Although the loss of property is felt,” Senator Mason of Virginia said for instance, “the loss of honor is felt still more.” The measure was also calculated to strike against the underground railroad, a legendary but loose organization that helped and sheltered the people who escaped their enslavement. “Magnified by southerners into an enormous Yankee network of lawbreakers who stole thousands of slaves each year”, the underground railroad in truth only helped a couple of hundred of enslaved people, at most, the great majority of them coming from the Upper South. It must be pointed out, as David Potter does, that the abolitionists that seldom risked a great deal were also the most lionized by the achievements of the underground railroad, “which draws attention away from the heroism of the fugitives themselves, who often staked their lives against incredible odds, with nothing to aid them but their own nerve and the North Star”. “If anyone helped them”, Porter continues, “the evidence indicates that it was more likely to be another Negro, slave or free, who chose to take heavy risks, than a benevolent abolitionist with secret passages, sliding panels, and other stage properties of organized escape.”

Nonetheless, the very existence of the underground railroad and the personal liberty laws were offensive to the Southerners, who saw in them nullification of the Constitution and a persistent refusal to recognize their right to enslave people. The Fugitive Slave Act was seen as a way to remedy this problem, and as long as the North acquiesced and respected it, its finality, and thus that of the Compromise, could be maintained and further discord avoided. Naturally, this didn’t happen. Though the law was enacted by a thin margin by the combined votes of Democrats and pro-administration Liberals, the anti-slavery Liberals, most of whom would desert the party in favor of the new Republican organization, resisted it to the very end. Even after it had been signed into law by President Scott, the Republicans, and a large section of Liberals, saw in it a “covenant with the devil” that had turned the Federal government into a “dirty slavecatcher”.

Again, it was the principle of the law rather than its practical effect that arose the most bitter resistance to it. By protecting slavery to such an extent all over the United States, the law seemed to embrace the “slavery national” Southern doctrine that was fundamentally opposed to the “freedom national” interpretation of the Constitution as anti-slavery in a round-about way. The Fugitive Slave Act, said Senator Seward in a speech that was derided as “monstrous and diabolical”, was a compromise with “an unjust, backward, dying institution” that attempted to “roll back the tide of social progress”. Such a concession to slavery would prevent it from dying “under the steady, peaceful action of moral, social, and political causes, . . . and with compensation”. If slavery was maintained, “the Union shall be dissolved and civil war ensue, bringing on violent but complete and immediate emancipation.” It was, in total, a horrendous law that went against liberty and human rights, and even if it was constitutional “there is a higher law than the Constitution”.

The Higher Law doctrine contributed to the Republicans’ refusal to recognize the Compromise of 1857 as a final settlement of sectional disputes. Republicans could simply not accept it, and instead sought to resist it by all means necessary. Not only did Republicans file suits trying to get the Supreme Court to declare the Fugitive Slave Act unconstitutional, but new personal liberty laws were enacted in several Northern states and Republican congressmen attempted in vain to obtain the repeal of the law. Charles Sumner introduced no less than twenty motions to that effect, forcing Southerners and moderates to enact a new gag rule even though Sumner’s motions never came close to a majority. But they did command unanimity among the Republicans and even sometimes obtained a few Liberal defectors.

The anti-slavery aptitudes of Northerners helped give strenght to the Republican Party

Far more enraging for the South was the violent resistance to the act carried by several Northern communities. Mobs of African Americans and White abolitionists had been repealing slavecatchers for decades already, but the Fugitive Slave Act embittered the fight and gave it a new national significance. Fiery abolitionists like Wendell Philipps declared that they had to trample the law under their feet – “it is to be denounced, resisted, disobeyed”, said a Boston anti-slavery society, because “as moral and religious men, we cannot obey an immoral and irreligious statute”. Consequently, local anti-slavery societies and many biracial communities formed vigilance committees that warned Blacks against kidnappers and threatened slavecatchers. This led to many dramatic scenes throughout the North, though the “cockpit of the new revolution” remained in the cockpit of the old one – Boston.

One of the most “dramatic flights” was that of William and Ellen Craft, a black couple whose escape from Georgia “had become celebrated in the antislavery press”. Their former owner had come to Boston to try and re-enslave them, vowing to capture them even “if we have to stay here to all eternity, and if there are not men enough in Massachusetts to take them, we will bring them some from the South”. Theodore Parker, a local clergyman, was decided to prevent this. Parker guarded the Crafts in his house, where he kept a “veritable arsenal” alongside the revolver he always carried. The enraged slaveholder tried to break into Parker’s house with the help of the Federal marshals and some men he had brought from the South, which started a riot that ended with him and other man dead. By the time that troops had restored order, the Crafts were already in a ship to England.

The strong Southern backlash forced President Scott to extent his aid, offering “all the means which the Constitution and Congress have placed at his disposal” to enforce the law. Scott did not do this out of love for slavery. Indeed, Old Fuss and Feathers was naturally anti-slavery, but he believed his major obligation was the maintenance of the Union, which necessitated the maintenance of the Compromise. But the Bostoners remained defiant. “I would rather lie all my life in jail, and starve there, than refuse to protect one of these parishioners of mine,” Parker told Scott. “You cannot think that I am to stand by and see my own church carried off to slavery and do nothing.” The Craft drama was repeated when a mob liberated a black man named Shadrach “out of his burning, fiery furnace” by overwhelming the Federal marshals that had captured him and sending him to Canada. “I think it is the most noble deed done in Boston since the destruction of the tea in 1773”, exulted Parker.

Attempts to enforce the penalties of the law failed as well, as Boston juries refused to convict any men who had taken part in these riots or aided fugitive slaves. “Massachusetts Safe Yet! The Higher Law Still Respected,” celebrated anti-slavery journals, while conservative newspapers and Southerners denounced “the triumph of mob law” and how Boston had been “disgraced by the lowest, the meanest, the blackest kind of nullification”. Especially humiliating was the failure of the Scott administration to punish those who nullified the law, and soon enough the South threatened secession again: “unless the abolitionist rioters are hung . . . WE LEAVE YOU! . . . If you fail in this simple act of justice, THE BONDS WILL BE DISSOLVED.” Violent acts that often resulted in the death of slavecatchers and the liberation of fugitives took place in many Northern communities aside from Boston, such as Syracuse or Christiana.

The Scott administration found it hard to enforce the Fugitive Slave Act. Not only did Northern juries and judges refuse to cooperate, resulting in the complete exoneration of those who had taken part in these rescues, but trying to bring down the force of the government only made martyrs out of the abolitionists and increased sympathy for their cause. Already reviled for their Compromise with the Slave Power, the Administration found that the enforcement of the act only resulted in losing strength within the North, something they could not afford when the Liberal Party was already dead in the South due to its support for peace during the war. Moreover, at the same time that these daring efforts for freedom were taking place, Southern filibusterers were attacking Cuba and Central America, and Scott’s failure to stop them proved to be more embarrassing. If Scott brought all his powers against the abolitionists but failed to do so against the filibusterers that would be irrefutable proof of his alliance with the Slave Power – and also a foreign policy disaster for the filibuster expeditions had alienated Mexico, Colombia and Britain.

Slavecatchers were violently driven away

Northern resistance to the act should not be overstated. Of hundreds of re-enslaved people, Northern communities only rescued a handful. “The law was defied primarily by spiriting slaves away before officers found them, rather than by resisting officers directly”, and indeed, after the first couple of years the number of escapees captured dropped sharply because most off the vulnerable had fled to Canada (Toronto’s Black population doubled). The commercial elites of the North, the hated “Lords of the Loom” who had supported the Compromise with the “Lords of the Lash” in order to assure stability and continued commerce, extended their hearty support, not out of love for slavery itself but in an attempt to prevent Civil War. Declarations that the law was enforced without troubled everywhere but Boston failed to conciliate the South, however, for the slavocrats were increasingly convinced that the North would not respect the Compromise and could not be trusted to respect Southern rights. In that case, the only answer was secession. At the same time, the Republican party was gaining strength as the only way to prevent the complete victory of the slave power. Far from settling the controversy, the Compromise had only created a far more bitter sectional and partisan struggle.

Proof of that were the 1857 midterms, which took place later in the year the Compromise was passed and which showed that the Republican revolt was not a mere brief-lived tantrum, but a complete political realignment. Throughout the North, Democrats and the Liberals were defeated in bruising contests where they were portrayed as pawns of the Slave Power. Similarly, to how the Liberals had for all purposes ceased to exist in the South, the Democrats organization was already in the throes of death, all its members reviled due to their support for war for slavery that had taken so many sons, husbands and brothers. The Fugitive Slave Act, the filibuster expeditions and events in Nebraska helped seal their fate, and the Democracy was basically exterminated.

If Democrats were blamed for the Slave Power’s measures, Liberals were blamed for falling to stop them. The Liberal ruin wasn’t complete, but many Liberals went down in defeat. Only in the “Lower North” areas of Ohio, Illinois and Indiana did Liberals hold, elected by moderates who didn’t like slavery but didn’t like abolitionism either. In most of the North the Republicans swept to victory, showing a decisive repudiation of the Compromise and the growth of anti-slavery sentiments. The defeat was a severe blow to the administration, which believed that it could count on moderate Northerners to show Yankee commitment to the Union and Compromise. It was also a strong hit against Southern faith in the Union for it showed that the North had not accepted the Compromise after all.

Instead of forcing the administration to grow closer to the South, the midterms forced it closer with the Republicans, who were willing to back and support Scott if he showed “that he could emancipate himself from the Slave Power”. The South, meanwhile, elected a “motley throng” of fire-eaters and secessionists that were bitterly opposed to the administration and the North. Compromise with them was impossible unless Scott accepted measures that would destroy him and what remained of the Liberals in the North. Wishing to hold into power, and be reelected in 1861, as the only way to stave off conflict by preventing a pro-slavery Southerner from being elected, Scott and the Republicans became closer. No formal agreement was made, but a tentative coalition between Liberals and Republicans that could control the House was being envisioned as a counter to the still Democratic Senate. Such a counter would be needed when Southerners, both federal and state, started to push for making a new slave state out of Nebraska.

An obvious antipathy to the Compromise was evident throughout the North

The Compromise of 1857 included a measure that repealed the Missouri Compromise, made decades ago, allowing Southerners to enter the territories with their slaves. This was of the utmost necessity for the South, because otherwise those territories would inevitably turn into free states that would presumably vote for anti-slavery measures. The fact that the war had been ended early due to Northern wickedness, at least in Southern eyes, made the need more pressing, because otherwise it meant that the primarily Southern Army had sacrificed so much for territories that would be closed to them. However, the Missouri Compromise had long been regarded as “a sacred covenant sanctified by decades of national life”, whose repeal could raise a “hell of a storm” that would make “even the bloody battles in Louisiana and Veracruz look like a gentle shower.” Like the Fugitive Slave Act, the repeal was passed by thin margins. But Northerners were decided to resist it, this time with more energy because there was a clear goal: keeping the slavocrats out of Nebraska and making it a free state.

“Since there is no escaping your challenge”, declared Seward, doubtlessly after recouping some of the Higher Law fire, “I accept it in behalf of the cause of freedom. We will engage in competition for the virgin soil of Nebraska, and God give the victory to the side which is stronger in numbers as it is in right.” The fact that Seward, who had supported compromise and was the Administration’s spokesman, was the one throwing down the gauntlet is significant, for it shows that repudiation of the repeal was strong even among moderate men, and that the President and his circle didn’t wish for new slave states to be accepted. In the South, this smacked of betrayal, for Southerners had understood that the repeal of the Compromise would guarantee the creation of new slave states that would “join their sisters in the protection of our holy institutions”. If the administration and Northerners fought to keep the territories free, then there was no substantial difference and the Compromise was worthless. But the slavocrats would not give up easily, and what could not be enacted by law could be enacted by blood.

Northerners, aided by Emigrant Societies funded by and coordinated from New England, poured into Nebraska at the same time as Missourians and other Southerners, together with their slaves, did. “The game must be played boldly”, Senator Atchison declared. “We will be compelled to shoot, burn and hang, but the thing will soon be over. We intend to ‘Mormonize’ the Abolitionists.” Groups of “ank, unshaven, unwashed, hard-drinking Missourians”, fueled by their hate for "those long-faced, sanctimonious Yankees" and their "sickly sycophantic love for the nigger”, poured into the enormous territory with the full intent of driving all Free-Soilers out and secure it for slavery.

The territorial governor, a certain Nathan S. Faulkner, a veteran of the Mexican-American War, was not about to accept these illegal efforts. Though certainly not a fiery abolitionist, Faulkner had no love for the institution either, and the use of violence and fraud by the “Border Ruffians” drew him closer to the Free-Soilers. The declarations of prominent Border Ruffians didn’t help matters: "Mark every scoundrel among you that is the least tainted with free-soilism, or abolitionism, and exterminate him . . . Enter every election district . . . and vote at the point of a Bowie knife or revolver!" The first task was to divide the enormous Nebraska into more manageable territories – indeed, the fact that the territory was so enormous was intentional, for it was hoped that would delay a fight and could lead to two different states being settled, preserving sectional balance. But Southerners wanted all or nothing, and they voted for the creation of a big state that would take most of the border with Missouri.

Faulkner, with the tacit blessing of the Scott administration, repudiated these proceedings. Aside from intimidation and ballot stuffing, the territorial governor cracked down on the violence that had started to cover the territory with blood. Soon enough, Free-Soilers, now known as Jayhawkers, started to fight tense and bloody battles against Border Ruffians all over Nebraska, though the most bitter fight was in the area of settlement near the Missouri border. There, Atchison led a band of Border Ruffians that attacked the Free-Soil capital at Lawrence, named after one of the Emigration Aid Society’s benefactors. The result was a pitched and bloody fight, that saw many buildings sacked and bombarded. Faulkner attempted to rally the Federal troops at his disposal to put it down, but to his horror he found that many were Southern veterans that saw in Nebraska a just price for their sacrifice. Instead, Faulkner had to rely on Northern veterans that still seethed at how the Slave Power had forced them to fight the war. The groups divided and the fight only grew bloodier and more intense.

The Battle of Lawrence

By the time the dust settled, it did so over more than 300 dead men and a completely destroyed town. Faulkner had been badly wounded, but he would survive, unlike Atchison, who fell in battle. News of the “Battle of Lawrence”, alternatively called the Lawrence Massacre, spread quickly. Southerners were horrified at how an administration officer had massacred the “innocent” Southerners that just wanted the government to honor their rights. Northerners hailed Faulkner’s defense of Lawrence, and cried against the Slave Power that had started that fight. A second battle started in Congress, that saw a Yankee congressman shot and a Southern one stabbed. Acts of political violence like that started to happen more often throughout the Union, and Nebraska continued bleeding. It was clear that the Union was tottering to its destruction, but on which terms that would happen was to be determined by the results of the next presidential election, which would take place in just a year. Still, as Southerners and Northerners armed and prepared for conflict, it did not take a prophet to see that Civil War was imminent.

@Red_Galiray How well there is a new update of my favorite TL, thank you very much compatriot for bringing another chapter again, please keep bringing us more updates on this fantastic story

I'm really happy I inspired you to write another one. I don't know if there are too many people following it or not, but it remains my favorite. As you said, it is something quite special. Thank you very much for all the good work!Your comment inspired me to finally write another chapter, Omar. I love this TL, but I must admit it's sometimes hard to muster enough will to write it since so few people read it. But your comment reminded me that that doesn't really matter. It's something special for me and for other people as well, so it's worth continuing even if it's not as popular as I'd like. It took me a while, but here's a new update after many months!

That's true, but there's a difference between "wheres the new chapter" and shows of support and appreciation that are not pushy like OmarI's.

Your comment inspired me to finally write another chapter, Omar. I love this TL, but I must admit it's sometimes hard to muster enough will to write it since so few people read it. But your comment reminded me that that doesn't really matter. It's something special for me and for other people as well, so it's worth continuing even if it's not as popular as I'd like. It took me a while, but here's a new update after many months!

I also want to voice my support of this timeline. I'm not well versed in Latin American history and so don't always have a lot to add to discussion, but I've been learning a lot by reading it and really enjoying it!!

I know this is supposed to be a Latin Ameican timeline so it's a little improper to be so excited about events in the United States, but it's cool to see TTL's cynical take on the American Civil War (to contrast Every Drop Of Blood's idealistic take) finally begin to unfold. The south seems to have an advantage in the political power balance, but we can't tell who will secede first. But if we already have gunfights in congress, it's clear things will be chaotic.

Interesting that the Southern States are considering secession over the failure to suppress abolitionism in the north. Are they so delusional that they still think they are oppressed, or do they just not want to too openly call for dropping the hammer on the northern states to avoid galvanizing them?

Curious what the culture of Toronto will be like, with how many American blacks fled there. How accepted are they by the locals?

Interesting that the Southern States are considering secession over the failure to suppress abolitionism in the north. Are they so delusional that they still think they are oppressed, or do they just not want to too openly call for dropping the hammer on the northern states to avoid galvanizing them?

Curious what the culture of Toronto will be like, with how many American blacks fled there. How accepted are they by the locals?

Don't worry, I will! Even if it sometimes takes a long time. And thanks!@Red_Galiray How well there is a new update of my favorite TL, thank you very much compatriot for bringing another chapter again, please keep bringing us more updates on this fantastic story

I'll be worse, that's for sure, since the North is much weaker and the South much stronger (in population, economy, industry), and the conflict much bitter.Things look grim in the good old US of A. I am excited to see how this weakened US will deal with the impending civil war...

It's also one of the few Latin American TLs we've got in this Anglo board. Thanks Omar.I'm really happy I inspired you to write another one. I don't know if there are too many people following it or not, but it remains my favorite. As you said, it is something quite special. Thank you very much for all the good work!

Your support is really appreciated!I also want to voice my support of this timeline. I'm not well versed in Latin American history and so don't always have a lot to add to discussion, but I've been learning a lot by reading it and really enjoying it!!

It did feel inappropriate to come back from the hiatus with an update about the US, but I do like these chapters especially because, as you point out, this TL features a cynical look at the US which contrasts with the idealist look of my other TL. And yeah, they are that delusional.I know this is supposed to be a Latin Ameican timeline so it's a little improper to be so excited about events in the United States, but it's cool to see TTL's cynical take on the American Civil War (to contrast Every Drop Of Blood's idealistic take) finally begin to unfold. The south seems to have an advantage in the political power balance, but we can't tell who will secede first. But if we already have gunfights in congress, it's clear things will be chaotic.

Interesting that the Southern States are considering secession over the failure to suppress abolitionism in the north. Are they so delusional that they still think they are oppressed, or do they just not want to too openly call for dropping the hammer on the northern states to avoid galvanizing them?

Curious what the culture of Toronto will be like, with how many American blacks fled there. How accepted are they by the locals?

Black people are still a minority but racism isn't so ingrained there. Especially in this world the success of Latin nations like Colombia and Mexico means that the idea that only white people can rule themselves isn't as widespread.

Oh cool you return, although it is a episode about EEUU, is good. Btw, ¿Will we see a episode about the relationship from Colombia with others Nations?

There are already a couple of episodes focusing on the relationships of Colombia with other nations. Chapter 56 The Eagle and the Condor focuses on the Colombia-US relationship, and Chapter 64 From the Andes to the Caribbean talks a fair bit about the Colombia-Mexico relationship.Oh cool you return, although it is a episode about EEUU, is good. Btw, ¿Will we see a episode about the relationship from Colombia with others Nations?

The Troubled Conga of the U.S continues...

Wonder how Canada sees the mess going with their southern neighbour and the rise of Latin America.

Wonder how Canada sees the mess going with their southern neighbour and the rise of Latin America.

I want to ask if we’ll have a Colombian-Chilean Sarawak or a Columbian Papua New Guinea, and the Philippines are supposed to be Mexican right? A successful colonisation of SEA by Latin America seems interesting.

PS: will we see an Argentina that’s a protectorate of Britain? That would be interesting.

PS: will we see an Argentina that’s a protectorate of Britain? That would be interesting.

Since the US is relatively poorer (no Great Lakes have stunted their growth) and much more inestable than in OTL, Canada has received a lot more immigrants. They are also somewhat more hostile to the US. But Canada remains sparsely populated and it's still a long ways from developing its own identity or path. Still, Canada follows Britain's opinions in most matters, and that includes a warmer relation with Latin America, especially Colombia which is considered part of the British sphere. The outlier, as always, it's Quebec. The success of the "Latin peoples" and France's stronger push for the idea of Latin America as a cohesive region has increased Quebec's nationalism and made them closer with Latin America - heck, they may even be counted as part of it by the TL's end! They also really like Mexico, because it's part of the French sphere - a stronger France means that many Quebecers look back on the French era with some nostalgia and kind of wish France retook them.The Troubled Conga of the U.S continues...

Wonder how Canada sees the mess going with their southern neighbour and the rise of Latin America.

I have thought of the first ones but they seem to be unrealistic. The Philippines are not Mexican, but Spanish. But yeah, I'd like to see some colonization there. And no, Argentina is not a protectora nor will it be one.I want to ask if we’ll have a Colombian-Chilean Sarawak or a Columbian Papua New Guinea, and the Philippines are supposed to be Mexican right? A successful colonisation of SEA by Latin America seems interesting.

PS: will we see an Argentina that’s a protectorate of Britain? That would be interesting.

Oh yes yes, although I was referring to other nations, like Prussia or Italy, but they are not so relevant to the story. But also, interesting chapter and how this US version is more unstable than normal. Btw, will there be stories or POV?

I have thought of the first ones but they seem to be unrealistic. The Philippines are not Mexican, but Spanish. But yeah, I'd like to see some colonization there. And no, Argentina is not a protectorate nor will it be one.

I’d think that Mexico and Columbia would have a big brother - little brother relationship to the Philippines as they’d have similar histories.

PS: if WW1 occurs, would the US fight Mexico and Latin America for Texas/rest of California and Cuba?

Last edited:

Threadmarks

View all 76 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 62: The Balkan War Chapter 63: The Liberal Revolution Appendix: The Colombian National Army Appendix: The Colombian Cavalry Appendix: The Colombian Artillery Appendix: The Colombian Navy Chapter 64: From the Andes to the Caribbean Chapter 65: The Irrepressible Conflict- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Share: