I've decided to start writing some mini biographies of characters of the TL, to make it easier for you all (and for myself) to follow. A kind of appendix, which I will update from time to time. I will also update the appendix with Presidents and Heads of State, and write a long overdue appendix about the Mexican Empire and its system of government. You can request mini biographies of characters whose fate you'd like to know!

1. Colombia.

"The size of your effort will be the size of your success."

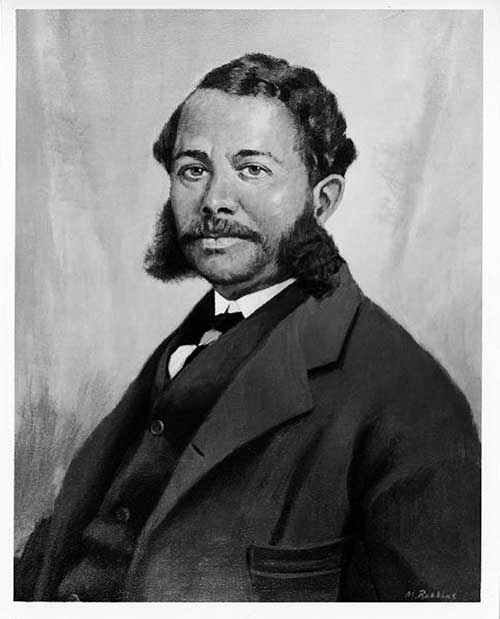

Generalissimo of the Republic of Colombia and its first President. Born in March 28, 1750, in Caracas, then part of the Spanish Empire. In 1771, he left Caracas and started his adventures around the world, which would take him to Europe and the United States, and have him participate in the American and French Revolution. In 1783, he met and fell in love with Susan Livingston, daughter of Chancellor Livingston. This brought Miranda closer to the American political elite, and affected him profoundly when it came to his views regarding Federalism and the need for joint action against Spain. He briefly returned to Caracas in 1784, re-establishing relations with the local elite, before going to New Granada and also establishing ties there. He took Susan with him to a new European tour, at the end of which Miranda settled briefly in Britain. He married Susan there, and they would have a son together, Leandro. Miranda's failure to get official support for his Latin American project frustrated him, but he established ties with many leading reformers and merchants. Miranda moved back to the US, and remained there until the start of the Latin American revolutions in 1809. Decided that Union was needed, he went to the Cartagena Junta, and then to the Federalist Tunja Junta, and convinced them to offer an alliance to the Caracas Junta. Caracas accepted after General Monteverde started to rally soldiers to the Royalist Cause. This eventually resulted in the formation of the Supreme Junta of New Granada and Venezuela, and the Proclamation of the Republic of Colombia in 1812. Miranda led the country as provisional President until the final victory over Peru. in 1816, he ran unopposed and was elected as President of the Republic, serving until 1824.

After playing a decisive part in the failure of Bolivar's coup d'état attempt, Miranda retired and moved to Caracas. He had brought Susan and his son to Colombia in 1815, and now they settled together in Miranda's old home. Miranda would serve as an important check on Venezuelan separatist, who steadily lost power thanks to economic recovery. A proud and even arrogant man who nonetheless held progressive and enlightened views, Miranda was sometimes a critic of the Santander administration, but largely supported it. He rallied volunteers and patriots during the Colombo-Peruvian War, and though at times he despaired and toyed with returning to Santafé, victory at Tarqui helped to convince him that the country was secure. Miranda enjoyed his status as the father of Colombia. He remained vain and proud, but also educated and affable, and maintained correspondence with several important figures of the world stage. His dream of going down in history as the Liberator of South America had been accomplished. He lived in tranquility in his Caracas estate. When it comes to personal relationships, he remained aloof from Bolívar, and generally respected men like Santander and Sucre. He died at 86 years old in August 19th 1836 in Caracas, an event that resulted in a wave of national mourning. His wife, nine years younger, survived him and would die 10 years later, when she was 87 years old. Their only son would live until the 1880's, never getting involved in politics.

Miranda is hailed as the greatest Colombian, and a true man of the enlightenment. Colombians can be proud of how he intervened in every major revolution, and met practically every figure of importance of the XVIIIth century. Like with other historical figures, his flaws of pride and vanity have been forgotten in favor of emphasizing his legend. Fondly remembered as the Father of Colombia and admired almost universally, Miranda can rest in peace knowing that his dream of going down in history as the Liberator of the New World has been fulfilled.

"Colombians! The arms have granted you independence, but only the laws can grant you freedom."

Known as el General Santander and nicknamed the Man of Laws, he served as the Second President of the Republic of Colombia from 1824 to 1836. Born in Cúcuta, in April 2nd, 1792, he was a young law student in Santafé when the Massacre occurred. A firm patriot and a federalist, Santander travelled north and joined the forces of the Tunja Junta. Later, the Supreme Junta was formed, and they welcomed the Venezuelans who fled from Monteverde. Royalists coming from Santafe attacked Tunja, but the Granadino soldiers and some Venezuelan reinforcements recently arrived managed to stop them at the Boyaca Bridge, thus saving Colombia. Afterwards, a second insurrection took place in Santafe and much of the garrison deflected, allowing the Patriots to move to the city and take the armory and treasury. The Supreme Junta moved there, and would soon declare the Republic of Colombia. Santander personally took part in all of these glorious events. Now a general, he was sent north to serve together with other Venezuelan forces in the campaigns around the Magdalena. A talented and able man, Santander quickly gained fame, though he was eclipsed by Simon Bolivar. Bolívar would go to Venezuela in his Admirable Campaign, while Santander remained around Cartagena. In 1814, he took part in the lifting of the siege of Cartagena. His popularity among Granadinos and his great commitment to law and order made Miranda chose him as his Vice-President in 1816, with the Constitution having been explicitly written so as to allow him to serve despite his young age.

Santander was mostly a representative of Granadino Liberalism during the Miranda administration. He developed ties with Venezuelan officers and politicians who otherwise were suspicious of him, but at the same time he gained the enmity of Antonio Nariño, who led a group of conservatives against the Administration. He went on to win the 1824 Presidential Election as the Federalist candidate against the Centralist, Bolívar. The dirty and hard-fought campaign had already strained their relationship, and when Bolívar attempted a coup, it was definitely broken. Santander was known for his commitment to the law and the constitution, thus Bolívar's action were unacceptable. The coup failed and Santander assumed the Presidency. He never took any punitive actions against Bolívar aside from offering him some far-off posts (which Bolívar refused). Both men would remain bitter enemies for the rest of their lives. Santander ruled with the help of a Liberal coalition, which included several Venezuelans and Southerners who benefited from free trade and modernization, and wanted even more federalism.

As President, Santander was an efficient administrator. He was personally very irritable when it came to criticism, asking Congress to investigate even petty accusations. Yet he never deviated from the law. He was also known as a throught statesman, that worked tirelessly, setting a rigid schedule and reading every bill and decree that came to his desk. He would even correct the grammar of the decrees before singing them, and reportedly didn't even have time to eat. Foreign diplomats compared him disfavorably with Miranda, because while Miranda had been a gracious host, Santander was stingy. He worked hard, and though many personally disliked him, especially separatist who called him a "Granadino Alzado" and other nicknames, he was known for being pragmatic in the persecution of his ideals. Nariño also left behind many bitter enemies of Santander's liberal administration, which would ultimately coalesce in the Centralist Party. Despite these difficulties, Santander managed to pull through and lead the country to victory during the Colombo-Peruvian War, which earned the love and trust of many. His selection of Marshal Sucre as his minister of War strengthened the ticket in Venezuela and among soldiers.

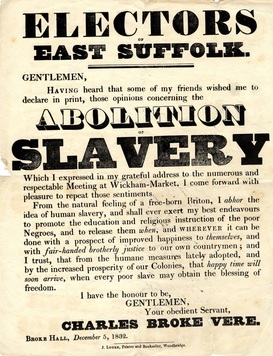

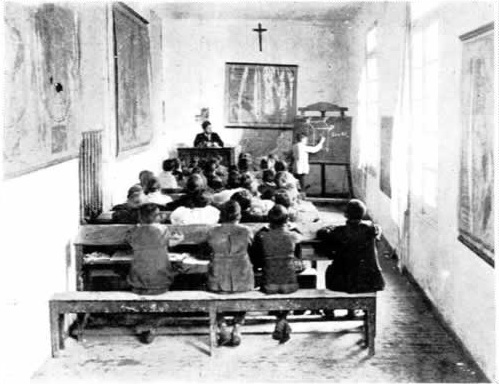

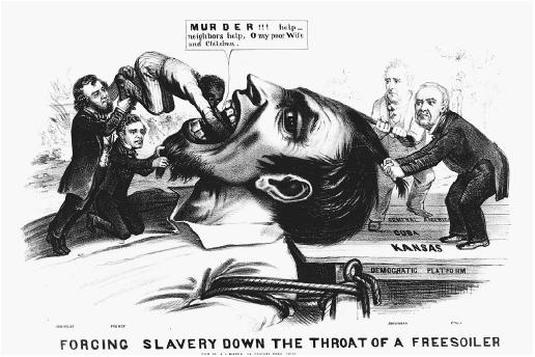

The war had consolidated the nation, giving a powerful coup de main to the Venezuelan separatists, who were unable to threaten Colombia's unity by themselves ever again. Santander now had enough political capital to pass his Great Reforms, a series of important laws that strengthened and expanded education in Colombia, encouraged immigration and the settlement of land, started the process of industrialization and the diversifying of the economy, and created a more rational and democratic system of governance. The Great Reforms are Santander's crowning achievement, which basically laid down the blueprint for modern Colombia. Other great achievement of his was the perpetual abolition of slavery in Colombia in 1833, despite the opposition of some slave-owners.

However, 12 years overworking himself as President took their told, and just two years after leaving office, Santander had fallen seriously ill. He did everything he could to rally support during the Grand Crisis, but his illness stripped the Federalists of the leadership they needed. After the Grand Crisis, Santander remained ill and would die in March 18th, 1844, at the relatively young age of 52, his plans for a Federalist comeback never realized. President Esteban Cruz decreed a week of national mourning, and although El Hombre de las Leyes still aroused passionate feelings within many, most regretted his death. When it comes to his personal life, Santander is known to have had a few passionate loves, including with Doña Nicolasa Ibañez. He fathered a total of five sons, all of whom went into politics. He would finally settle with Sixta Ponton in 1836. Their son, named Francisco de Paula just like his father but known by his mother’s surname, served as Senator for Boyacá.

Santander left behind a legacy as the greatest Colombian liberal. His name and policies were venerated in an almost sacred manner by the next generation of liberals, who often cited him as the greatest statesman of his time. Many men of great reputation themselves, such as Noboa and Armas, mentioned him as their inspiration. Santander has often topped lists of the greatest Colombian presidents, and his legacy is felt even today.

"Maintaining the balance of liberty is harder than enduring the weight of tyranny."

El Libertador Simon Bolivar, the final member of the legendary Colombian triumvirate that brought independence to the South American Nation. Born in July 24, 1783 in Caracas, Bolivar was the son of one of Caracas' oldest and most respected families. Tragedy quickly struck them, however, for his father died when he was but a child, and his mother a few years later. Bolivar grew in comfortable conditions, as an unruly child who liked to roam Caracas and could not be tamed by any kind of tutor. His family had large estates, slaves (including the famous Hipolita, whom Bolivar loved as a mother) and mines. Destiny seemed to prep him for a comfortable and obscure life as a landowner. The only tutor who managed to get to him was Simon Rodriguez, who instituted a love for liberty and the doctrines of the enlightenment. Yet Bolivar did not show any interest in becoming a statesman. The young man travelled to Spain to continue his studies, and there he met and fell in love with Maria Teresa Rodriguez del Toro. They married, but when they came back to Caracas María fell ill, and died.

Feeling lost and hurt, Bolivar returned to Europe. He felt disgusted at the decadence of Spain, and compared it unfavourably with France's splendor and progress. In the Monte Sacro in Italy he made a famous vow to never rest until his fatherland was liberated from the Spanish yoke, in the same place where the Roman plebs had started their revolt against the Consul. Bolivar then returned to Caracas, and offered his service to the Caracas Junta when the Revolution started. In those days, he was a fervent supporter of further union and cooperation with other American juntas, such as the Junta of Tunja. He and his supporters called themselves the "Patriotic Society", and quickly established contact with the Venezuelan Francisco de Miranda. But the zealous Caraqueños were not willing to fully cooperate yet. Bolivar fought admirably in the first battles of the war, but the Republicans were overwhelmed by General Monteverde's forces. The Caracas Junta accepted the alliance with the Granadinos then. Their leaders, Bolivar and some officers managed to evacuate Caracas, even as Monteverde unleashed a reign of terror over the patriots. Out of pragmatism or a genuine belief that they would be stronger together, the Venezuelans accepted to join the Granadinos, and they formed the Supreme Junta. It had to face a final Royalist attack, which was stopped at the Boyaca Bridge by a combined Granadino-Venezuelan force. His participation in the battle earned him a promotion to general.

Bolivar was put in charge of troops around the Magdalena, where he would for the first time met Francisco de Paula Santander. After the successful end of the campaign, he launched his Campaña Admirable, which saw him defeat Spanish force after Spanish force and take town after town with the help of an united army of Venezuelans and Granadinos, retaking Caracas in 1813. It was there that he received his famous title of El Libertador, being welcomed by big celebrations that included a dance by several young ladies in white dresses. Bolivar would go on to defeat the Royalists decisively at Carabobo, which trapped them in Maracaibo and Puerto Cabello. Afterwards, he went South and again defeated a Spanish attempt to take Santafe, thus securing the capital from this final try at reconquest. The Spanish would never again take the initiative. Bolivar led the army South, sieging and taking Quito, and then Lima. He would end the war at the Battle of Ayacucho, which forced the surrender of the final Royalist forces in South America.

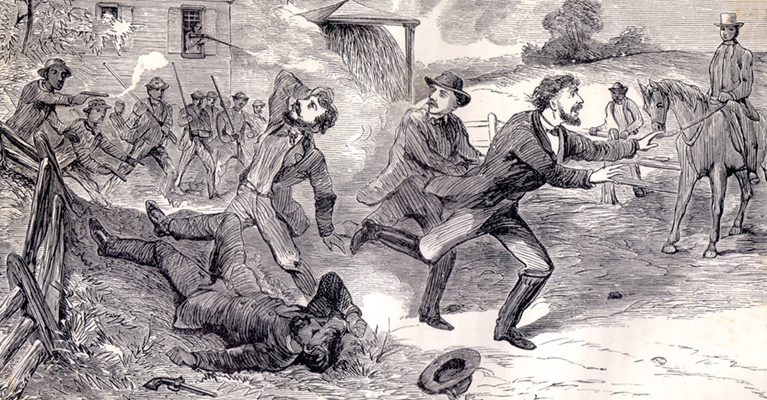

Following his dreams of becoming the Colombian Washington, Bolivar simply intended to settle down as a farmer. He did briefly take up arms again to take part in the liberation of Hispaniola, beating back twin attacks by the Haitians and the Spanish, but for the most part he stayed off the public light during the first years of the Republic. However, he was displeased by the Democratic and peaceful direction the Miranda administration had taken, especially his demobilization of the army and his refusal to continue the war to take Cuba. Though he did no want to be a politician, he naturally became the rallying figure for conservatives and Venezuelan separatists, who hoped to use him to secure secession from Colombia. By 1824, they had convinced him that Santander was a snake who would destroy the "pobres militares" and Venezuela if allowed to take command. The execution of Leonardo Infante, widely considered a miscarriage of justice, and the persecution of the corrupt Miguel Peña served to convince him. He ran against Santander in the 1824 election, but lost. Undeterred, he attempted a coup, storming Congress with a core of loyal soldiers and officers. But he found that there was neither popular support, nor political support for him. The fact that Venezuelan separatist elected to Congress refused to take their seats meant that there was no one to speak for him in Congress. Bolivar realized that the separatists had tricked him. Feeling betrayed, he issued a warning against any rebels, saying that he would personally ensure Colombia's unity with his sword if necessary. After the coup attempt, Zulia, Apure, Maturin and some Venezuelan cities like Valencia and Barcelona all issued declarations of their support for Santafe and the Colombian union.

Bolivar's mere presence was enough to deter any attempt at separatism, since no general or politician dared to cross him. There were some hopes that he would lead another coup or separation attempt during the Colombo-Peruvian War, but then Marshal Sucre turned the tide at Tarqui. Victory consolidated the nation, and gave a final coup de grace to Venezuelan separatism. Yet Bolivar felt restive and out of place in the Liberal Colombia that Santander was building. He finally decided to exile himself like San Martin had done, and went to live in Britain for a few years. He did not find respite there either. In 1840, he travelled to Brazil by invitation of the Emperor. He stayed for around a year, before moving to Paraguay. When the Triple War started, he offered his services to the Paraguayan government, and was instrumental in several victories over the Brazilians and Platineans. But again, his soul remained restive. After writing a new constitution for Paraguay, Bolivar sailed North and returned to Caracas in 1851, the first time he set foot in his home in 15 years. He was once again welcomed by young ladies in white dresses and cries of "hail El Libertador!" Bolivar died soon after that, having largely fulfilled his dream.

The legacy of Bolivar is still difficult to judge. Some point to his authoritarian streak, his coup attempt, and his attempts to start a bloody "War to the Death" as fatal flaws of character. But at the same time he was determined, hard working, and charismatic. Even if he was misguided, there is no doubt that he always wanted the best for Colombia and his people, and that he truly and deeply loved his country. He left a mark in the conservative movement, which saw his principles as their guiding light even if he never held elected office. But by far his greatest legacy was conquering Colombia's freedom. Despite his mistakes and flaws, no one can deny that he was instrumental in the founding of Colombia and the achievement of independence.

2. México

"Mexicans! We have before us a great ordeal. Just like the Spanish, these Americans are now trying to force our Mexico into the dark piths of suffering and fear. But just like before, the brave men of Mexico will rise to fight them."

Mexican commander, known as the Victor of New Orleans for his defeat of Zachary Taylor, which earned him the title of Marshal of the Empire. Born in September 2nd, 1811, in México City, Ruiz was the son of a merchant and commander of the Trigarante Army, who had earned a noble peerage for his loyalty towards Emperor Agustin I. Raised in comfortable richness, Ruiz quickly decided to become a military man, obtaining an appointment to the National College of the Armed Forces in 1827 - two years short of the required age of 18, but he obtained a special permission. He showed decision and assertiveness, and a talent for the command of artillery, supporting reforms within the armed forces that would lead to the switch to "flying artillery." Appointed a colonel in the frontier army, Ruiz quickly rose through the ranks thanks to a combination of personal charisma, connections, and raw talent. During the crisis of the 40's, Ruiz was commanding a corps of artillery that was attacked by a group of American filibusters. He dispersed them with ease and ruthlessness, earning accolades from Mexico city and the hate of the Texians. War was averted thanks to the Emperor's successful diplomatic maneuvers, but Ruiz was retained in the frontier, and given command of the army there, one of the youngest generals of the Empire. This earned the jealousy of many, such as General Gabriel Valencia. On the other hand, he forged friendships with men such as Augusto Noble, who would later become the commander of the Indian Cavalry.

Though his family wanted Ruiz to get involved in politics, he refused, feeling more comfortable as a military man than a statesman. He married the daughter of a Member of Parliament for the National Patriotic Party in 1847, but reportedly did not discuss politics with her. He remained rather apolitical, though he was a firm nationalist and an enthusiastic monarchist. In his personal life, Ruiz was known for portraying an image of a secure, affable and brave man, but internally he often questioned and second-guessed himself. At times, he seemed to suffer from crippling depression. The loving relation he developed with his wife, Doña Camila Sierra de Ruiz, helped him. He was, however, an aloof and demanding father, seemingly because he wanted to make sure his children would be able to fend for themselves. He was similar in his relations with his men, being prone to launching into motivational speeches but also demanding and enforcing strict discipline. The men loved him for the most part, finding him fair and unpretentious. Though he enjoyed the battles at first, the bloody war would change his opinion as the casualties mounted. And even if he hated to be harsh with civilians, he was ruthless in his dealings with guerrillas. Many have also noticed great apathy on his part towards the slaves and indigenous soldiers, though he always treated them with dignity and respect. He definitely shared the prejudices of his era.

When the Mexican-American war started, Ruiz rose to prominence as the commander of the army closest to the frontier. He was supposed to simply delay the Americans, but he turned them back at San Jacinto and invaded Louisiana. He was subsequently promoted and given command of all Mexican troops in the area. His successful campaign, called the Eagles Offensive, would give him fame and recognition, though he seemingly didn't crave either. "Lighting Ruiz" as he came to be known, would defeat Taylor and take New Orleans, starting a year of military occupation, during which his anxiety and depression only grew as he found himself outside of his element, and this reflected on his skills as a commander. He had special trouble coordinating with his lieutenants, especially Valencia. In the Battles of Avoyelles, he dithered and held off reinforcements even as Valencia fought tooth and nail against the Americans. He paid dearly for the mistake. A sharpshooter's bullet would end the life of the Marshal during the battle at Breaux Bridge. Ruiz left behind a legacy as one of Mexico's greatest military heroes, but one of the most hated foes of the United States as well, being seen as a butcher and a tyrant - to this day, many refer to him as "King Lewis" and talk of the atrocities of the Mexican occupation of Louisiana. His army was taken over by Valencia, who was never able to instill the same pride and loyalty as Ruiz did. History would make many forget his flaws, and the government of Salazar often used his image as a rallying point. His widow, two sons and a daughter survived him, and although they formed a personal friendship with Marshal Salazar, who offered a sizable pension, they stayed off the public scene.

"The horrible privations of war should teach us to appreciate peace, to grant forgiveness, and to toil for prosperity."

Mexican general and statesman, hailed as the Hero of Veracruz for his successful defense of the Port City during the Mexican-American War. Born into a poor family in Puebla, in March 23, 1803, Salazar was always attracted to military life, watching the militias drill around the city square. He stayed out of the first chaotic stages of struggle for Independence, but joined the army as a drummer boy in 1816 when Agustin I formed the Trigarante Army, which instilled in him a lifelong loyalty to the monarchy and to order. Two years later, he had obtained a command as a lieutenant due to his sheer talent and bravery. After the war, he enlisted in the National College and obtained the education he had lacked. Appointed a commander, he earned the affections of his superior officer, who helped him rise through the ranks. Yet, Salazar’s conflictive aptitude, his low birth and poor economic status, and his frequent insubordination stalled his career. When his superior officer retired, the higher ups decided to get rid of the problematic colonel and appointed him to the Army of Central America, which was seen as an army of cutthroats and thieves. Salazar turned things around and instilled pride and discipline in his men, earning their loyalty and admiration. At the same time, he became infamous due to his cruelty and ruthlessness towards the native population.

His status as an officer allowed Salazar to marry with the daughter of an hacendado, something that would usually be off limits for someone from a poor family. The relation was good, even genuinely loving at times. Salazar was, however, a frequent womanizer and liked to drink, though he was never abusive towards his wife or his children. Strict and demanding, Salazar was known for being easy to anger and hard to please, but he also was bright, capable and could even be charismatic and grandiose. He was not afraid of showing attention from time to time, looking at affection as a reward. He also showed extreme loyalty and diligence, which earned the trust and affection of many. The story of how he did not forget his mother and father and did everything to give them a comfortable life after becoming an officer is well known. In any case, Salazar's refusal to engage in empty flattery and his non-aristocratic manner stopped his military career. Had it not been for the war, he may have languished in obscurity.

When the war came, Salazar and his army were transferred from Central America to the frontlines at Veracruz. By the time he arrived, the situation had turned desperate. General Veintimilla, who assumed command after the death of Zapatero, proved unsuited to the task at hand. After his nervous collapse, Salazar assumed command and drove back the Americans with the famous war cry of "No gringo shall set a foot in Agustin I's Plaza!" As a general, Salazar was a capable administrator, and his personality attracted the loyalty of his lieutenants, men of difficult personalities that Salazar managed to nonetheless balance effectively. He suffered enormously due to the sight of horrible tragedy that struck Veracruz, which manifested itself in an undying hatred for the US. He seems to have developed a firm belief that he was the chosen instrument of God for the salvation of Mexico, even if he was not particularly religious before the war, and would not become a devout believer even after it. He finally managed to force the surrender of Patterson, giving him the title of the Hero of Veracruz and the national fame and glory that he had so desperately wanted even from his days as a drummer boy. Afterwards, Salazar joined the conspiration known as the Plan of Veracruz, which wanted to overthrow parliament to assure a successful prosecution of the war without the weight of petty politics dragging them down. Not a friend of direct democracy, Salazar was not a tyrant either, and he favored constitutional, limited government. Yet the experience in Veracruz and the fight between Parliament and Empress Louise convinced him that Parliament had to be out of the way for Mexico to be saved. He led the coup and installed himself as President of the Regency Council under Princess Isabel. After the war, he restored Parliament and obtained a seat from Mexico city, and continued as Head of Government as Prime Minister.

"Let us work together, for we can only achieve an united and prosperous Mexico when the people are educated and laborious."

Eldest daughter of Emperor Agustin II and Empress consort Louise, and Princess Regent of Mexico for her brother the Emperor Carlos I. Born in July 28th, 1833 in Mexico City, Princess Isabel grew in the peaceful and prosperous later half of her grandfather's reign. She was known for being an independent and sweet girl, who preferred to run around playing instead of learning etiquette. Her grandfather adored her, and nicknamed her "Little Flower." As she grew up, she learned to be more disciplined. She especially discovered a love for literature, importing several European books and learning English and French. She also developed an appreciation for politics, though according to Agustin II she was remarkably naïve, thinking that all nations always had the best interests of their peoples in mind. Her curiosity pushed her towards travelling her Empire instead of remaining in the palace. To her father's dismay, she often liked to talk to commoners and even tried street food once.

Her aptitude earned the appreciation of the people of Mexico city, and soon enough she was declared the "Fairest Flower of Mexico". Her independent spirit still remained within her, and she sought to have a voice in the nation's politics. For example, she befriended her father's personal friend, Eduardo Castillo, then a simple Member of Parliament but later the leader of Mexico during the war. She also travelled to various points of the Empire, though her father forbade her from leaving the country barring a brief sojourn in the Colombian Caribbean. She was the Heir Presumptive until the birth of her brother Carlos Augusto in 1842, and as such received a complete education. But she was always more interested in the human aspect, and she led several social programs in favor of the poor and needy, which only increased her popularity.

At the start of the war she did what was expected of her - help in galas and other reunions in the palace as a hostess. But when the Battle of Veracruz started, she went against her father's wishes to the front and served as a nurse of the 3M, directly helping several poor soldiers. She met Marshal Salazar there, a man with whom she would establish a fatherly bond. When her father died, a political struggle started because her mother wanted to establish herself as regent against the wishes of Parliament. Her relation with her overwhelming mother had always been tense, and it broke as a result of the crisis. She accepted to form part of Salazar's Plan of Veracruz, and was installed as regent. She largely referred to Salazar's genius as an administrator and politician, but she did push for several laws in favor of the needy of Mexico. Her personal diary is a good account of the Mexican-American War, and it also shows her genuine pain at the suffering of her people.

1. Colombia.

"The size of your effort will be the size of your success."

Generalissimo of the Republic of Colombia and its first President. Born in March 28, 1750, in Caracas, then part of the Spanish Empire. In 1771, he left Caracas and started his adventures around the world, which would take him to Europe and the United States, and have him participate in the American and French Revolution. In 1783, he met and fell in love with Susan Livingston, daughter of Chancellor Livingston. This brought Miranda closer to the American political elite, and affected him profoundly when it came to his views regarding Federalism and the need for joint action against Spain. He briefly returned to Caracas in 1784, re-establishing relations with the local elite, before going to New Granada and also establishing ties there. He took Susan with him to a new European tour, at the end of which Miranda settled briefly in Britain. He married Susan there, and they would have a son together, Leandro. Miranda's failure to get official support for his Latin American project frustrated him, but he established ties with many leading reformers and merchants. Miranda moved back to the US, and remained there until the start of the Latin American revolutions in 1809. Decided that Union was needed, he went to the Cartagena Junta, and then to the Federalist Tunja Junta, and convinced them to offer an alliance to the Caracas Junta. Caracas accepted after General Monteverde started to rally soldiers to the Royalist Cause. This eventually resulted in the formation of the Supreme Junta of New Granada and Venezuela, and the Proclamation of the Republic of Colombia in 1812. Miranda led the country as provisional President until the final victory over Peru. in 1816, he ran unopposed and was elected as President of the Republic, serving until 1824.

After playing a decisive part in the failure of Bolivar's coup d'état attempt, Miranda retired and moved to Caracas. He had brought Susan and his son to Colombia in 1815, and now they settled together in Miranda's old home. Miranda would serve as an important check on Venezuelan separatist, who steadily lost power thanks to economic recovery. A proud and even arrogant man who nonetheless held progressive and enlightened views, Miranda was sometimes a critic of the Santander administration, but largely supported it. He rallied volunteers and patriots during the Colombo-Peruvian War, and though at times he despaired and toyed with returning to Santafé, victory at Tarqui helped to convince him that the country was secure. Miranda enjoyed his status as the father of Colombia. He remained vain and proud, but also educated and affable, and maintained correspondence with several important figures of the world stage. His dream of going down in history as the Liberator of South America had been accomplished. He lived in tranquility in his Caracas estate. When it comes to personal relationships, he remained aloof from Bolívar, and generally respected men like Santander and Sucre. He died at 86 years old in August 19th 1836 in Caracas, an event that resulted in a wave of national mourning. His wife, nine years younger, survived him and would die 10 years later, when she was 87 years old. Their only son would live until the 1880's, never getting involved in politics.

Miranda is hailed as the greatest Colombian, and a true man of the enlightenment. Colombians can be proud of how he intervened in every major revolution, and met practically every figure of importance of the XVIIIth century. Like with other historical figures, his flaws of pride and vanity have been forgotten in favor of emphasizing his legend. Fondly remembered as the Father of Colombia and admired almost universally, Miranda can rest in peace knowing that his dream of going down in history as the Liberator of the New World has been fulfilled.

"Colombians! The arms have granted you independence, but only the laws can grant you freedom."

Known as el General Santander and nicknamed the Man of Laws, he served as the Second President of the Republic of Colombia from 1824 to 1836. Born in Cúcuta, in April 2nd, 1792, he was a young law student in Santafé when the Massacre occurred. A firm patriot and a federalist, Santander travelled north and joined the forces of the Tunja Junta. Later, the Supreme Junta was formed, and they welcomed the Venezuelans who fled from Monteverde. Royalists coming from Santafe attacked Tunja, but the Granadino soldiers and some Venezuelan reinforcements recently arrived managed to stop them at the Boyaca Bridge, thus saving Colombia. Afterwards, a second insurrection took place in Santafe and much of the garrison deflected, allowing the Patriots to move to the city and take the armory and treasury. The Supreme Junta moved there, and would soon declare the Republic of Colombia. Santander personally took part in all of these glorious events. Now a general, he was sent north to serve together with other Venezuelan forces in the campaigns around the Magdalena. A talented and able man, Santander quickly gained fame, though he was eclipsed by Simon Bolivar. Bolívar would go to Venezuela in his Admirable Campaign, while Santander remained around Cartagena. In 1814, he took part in the lifting of the siege of Cartagena. His popularity among Granadinos and his great commitment to law and order made Miranda chose him as his Vice-President in 1816, with the Constitution having been explicitly written so as to allow him to serve despite his young age.

Santander was mostly a representative of Granadino Liberalism during the Miranda administration. He developed ties with Venezuelan officers and politicians who otherwise were suspicious of him, but at the same time he gained the enmity of Antonio Nariño, who led a group of conservatives against the Administration. He went on to win the 1824 Presidential Election as the Federalist candidate against the Centralist, Bolívar. The dirty and hard-fought campaign had already strained their relationship, and when Bolívar attempted a coup, it was definitely broken. Santander was known for his commitment to the law and the constitution, thus Bolívar's action were unacceptable. The coup failed and Santander assumed the Presidency. He never took any punitive actions against Bolívar aside from offering him some far-off posts (which Bolívar refused). Both men would remain bitter enemies for the rest of their lives. Santander ruled with the help of a Liberal coalition, which included several Venezuelans and Southerners who benefited from free trade and modernization, and wanted even more federalism.

As President, Santander was an efficient administrator. He was personally very irritable when it came to criticism, asking Congress to investigate even petty accusations. Yet he never deviated from the law. He was also known as a throught statesman, that worked tirelessly, setting a rigid schedule and reading every bill and decree that came to his desk. He would even correct the grammar of the decrees before singing them, and reportedly didn't even have time to eat. Foreign diplomats compared him disfavorably with Miranda, because while Miranda had been a gracious host, Santander was stingy. He worked hard, and though many personally disliked him, especially separatist who called him a "Granadino Alzado" and other nicknames, he was known for being pragmatic in the persecution of his ideals. Nariño also left behind many bitter enemies of Santander's liberal administration, which would ultimately coalesce in the Centralist Party. Despite these difficulties, Santander managed to pull through and lead the country to victory during the Colombo-Peruvian War, which earned the love and trust of many. His selection of Marshal Sucre as his minister of War strengthened the ticket in Venezuela and among soldiers.

The war had consolidated the nation, giving a powerful coup de main to the Venezuelan separatists, who were unable to threaten Colombia's unity by themselves ever again. Santander now had enough political capital to pass his Great Reforms, a series of important laws that strengthened and expanded education in Colombia, encouraged immigration and the settlement of land, started the process of industrialization and the diversifying of the economy, and created a more rational and democratic system of governance. The Great Reforms are Santander's crowning achievement, which basically laid down the blueprint for modern Colombia. Other great achievement of his was the perpetual abolition of slavery in Colombia in 1833, despite the opposition of some slave-owners.

However, 12 years overworking himself as President took their told, and just two years after leaving office, Santander had fallen seriously ill. He did everything he could to rally support during the Grand Crisis, but his illness stripped the Federalists of the leadership they needed. After the Grand Crisis, Santander remained ill and would die in March 18th, 1844, at the relatively young age of 52, his plans for a Federalist comeback never realized. President Esteban Cruz decreed a week of national mourning, and although El Hombre de las Leyes still aroused passionate feelings within many, most regretted his death. When it comes to his personal life, Santander is known to have had a few passionate loves, including with Doña Nicolasa Ibañez. He fathered a total of five sons, all of whom went into politics. He would finally settle with Sixta Ponton in 1836. Their son, named Francisco de Paula just like his father but known by his mother’s surname, served as Senator for Boyacá.

Santander left behind a legacy as the greatest Colombian liberal. His name and policies were venerated in an almost sacred manner by the next generation of liberals, who often cited him as the greatest statesman of his time. Many men of great reputation themselves, such as Noboa and Armas, mentioned him as their inspiration. Santander has often topped lists of the greatest Colombian presidents, and his legacy is felt even today.

"Maintaining the balance of liberty is harder than enduring the weight of tyranny."

El Libertador Simon Bolivar, the final member of the legendary Colombian triumvirate that brought independence to the South American Nation. Born in July 24, 1783 in Caracas, Bolivar was the son of one of Caracas' oldest and most respected families. Tragedy quickly struck them, however, for his father died when he was but a child, and his mother a few years later. Bolivar grew in comfortable conditions, as an unruly child who liked to roam Caracas and could not be tamed by any kind of tutor. His family had large estates, slaves (including the famous Hipolita, whom Bolivar loved as a mother) and mines. Destiny seemed to prep him for a comfortable and obscure life as a landowner. The only tutor who managed to get to him was Simon Rodriguez, who instituted a love for liberty and the doctrines of the enlightenment. Yet Bolivar did not show any interest in becoming a statesman. The young man travelled to Spain to continue his studies, and there he met and fell in love with Maria Teresa Rodriguez del Toro. They married, but when they came back to Caracas María fell ill, and died.

Feeling lost and hurt, Bolivar returned to Europe. He felt disgusted at the decadence of Spain, and compared it unfavourably with France's splendor and progress. In the Monte Sacro in Italy he made a famous vow to never rest until his fatherland was liberated from the Spanish yoke, in the same place where the Roman plebs had started their revolt against the Consul. Bolivar then returned to Caracas, and offered his service to the Caracas Junta when the Revolution started. In those days, he was a fervent supporter of further union and cooperation with other American juntas, such as the Junta of Tunja. He and his supporters called themselves the "Patriotic Society", and quickly established contact with the Venezuelan Francisco de Miranda. But the zealous Caraqueños were not willing to fully cooperate yet. Bolivar fought admirably in the first battles of the war, but the Republicans were overwhelmed by General Monteverde's forces. The Caracas Junta accepted the alliance with the Granadinos then. Their leaders, Bolivar and some officers managed to evacuate Caracas, even as Monteverde unleashed a reign of terror over the patriots. Out of pragmatism or a genuine belief that they would be stronger together, the Venezuelans accepted to join the Granadinos, and they formed the Supreme Junta. It had to face a final Royalist attack, which was stopped at the Boyaca Bridge by a combined Granadino-Venezuelan force. His participation in the battle earned him a promotion to general.

Bolivar was put in charge of troops around the Magdalena, where he would for the first time met Francisco de Paula Santander. After the successful end of the campaign, he launched his Campaña Admirable, which saw him defeat Spanish force after Spanish force and take town after town with the help of an united army of Venezuelans and Granadinos, retaking Caracas in 1813. It was there that he received his famous title of El Libertador, being welcomed by big celebrations that included a dance by several young ladies in white dresses. Bolivar would go on to defeat the Royalists decisively at Carabobo, which trapped them in Maracaibo and Puerto Cabello. Afterwards, he went South and again defeated a Spanish attempt to take Santafe, thus securing the capital from this final try at reconquest. The Spanish would never again take the initiative. Bolivar led the army South, sieging and taking Quito, and then Lima. He would end the war at the Battle of Ayacucho, which forced the surrender of the final Royalist forces in South America.

Following his dreams of becoming the Colombian Washington, Bolivar simply intended to settle down as a farmer. He did briefly take up arms again to take part in the liberation of Hispaniola, beating back twin attacks by the Haitians and the Spanish, but for the most part he stayed off the public light during the first years of the Republic. However, he was displeased by the Democratic and peaceful direction the Miranda administration had taken, especially his demobilization of the army and his refusal to continue the war to take Cuba. Though he did no want to be a politician, he naturally became the rallying figure for conservatives and Venezuelan separatists, who hoped to use him to secure secession from Colombia. By 1824, they had convinced him that Santander was a snake who would destroy the "pobres militares" and Venezuela if allowed to take command. The execution of Leonardo Infante, widely considered a miscarriage of justice, and the persecution of the corrupt Miguel Peña served to convince him. He ran against Santander in the 1824 election, but lost. Undeterred, he attempted a coup, storming Congress with a core of loyal soldiers and officers. But he found that there was neither popular support, nor political support for him. The fact that Venezuelan separatist elected to Congress refused to take their seats meant that there was no one to speak for him in Congress. Bolivar realized that the separatists had tricked him. Feeling betrayed, he issued a warning against any rebels, saying that he would personally ensure Colombia's unity with his sword if necessary. After the coup attempt, Zulia, Apure, Maturin and some Venezuelan cities like Valencia and Barcelona all issued declarations of their support for Santafe and the Colombian union.

Bolivar's mere presence was enough to deter any attempt at separatism, since no general or politician dared to cross him. There were some hopes that he would lead another coup or separation attempt during the Colombo-Peruvian War, but then Marshal Sucre turned the tide at Tarqui. Victory consolidated the nation, and gave a final coup de grace to Venezuelan separatism. Yet Bolivar felt restive and out of place in the Liberal Colombia that Santander was building. He finally decided to exile himself like San Martin had done, and went to live in Britain for a few years. He did not find respite there either. In 1840, he travelled to Brazil by invitation of the Emperor. He stayed for around a year, before moving to Paraguay. When the Triple War started, he offered his services to the Paraguayan government, and was instrumental in several victories over the Brazilians and Platineans. But again, his soul remained restive. After writing a new constitution for Paraguay, Bolivar sailed North and returned to Caracas in 1851, the first time he set foot in his home in 15 years. He was once again welcomed by young ladies in white dresses and cries of "hail El Libertador!" Bolivar died soon after that, having largely fulfilled his dream.

The legacy of Bolivar is still difficult to judge. Some point to his authoritarian streak, his coup attempt, and his attempts to start a bloody "War to the Death" as fatal flaws of character. But at the same time he was determined, hard working, and charismatic. Even if he was misguided, there is no doubt that he always wanted the best for Colombia and his people, and that he truly and deeply loved his country. He left a mark in the conservative movement, which saw his principles as their guiding light even if he never held elected office. But by far his greatest legacy was conquering Colombia's freedom. Despite his mistakes and flaws, no one can deny that he was instrumental in the founding of Colombia and the achievement of independence.

2. México

"Mexicans! We have before us a great ordeal. Just like the Spanish, these Americans are now trying to force our Mexico into the dark piths of suffering and fear. But just like before, the brave men of Mexico will rise to fight them."

Mexican commander, known as the Victor of New Orleans for his defeat of Zachary Taylor, which earned him the title of Marshal of the Empire. Born in September 2nd, 1811, in México City, Ruiz was the son of a merchant and commander of the Trigarante Army, who had earned a noble peerage for his loyalty towards Emperor Agustin I. Raised in comfortable richness, Ruiz quickly decided to become a military man, obtaining an appointment to the National College of the Armed Forces in 1827 - two years short of the required age of 18, but he obtained a special permission. He showed decision and assertiveness, and a talent for the command of artillery, supporting reforms within the armed forces that would lead to the switch to "flying artillery." Appointed a colonel in the frontier army, Ruiz quickly rose through the ranks thanks to a combination of personal charisma, connections, and raw talent. During the crisis of the 40's, Ruiz was commanding a corps of artillery that was attacked by a group of American filibusters. He dispersed them with ease and ruthlessness, earning accolades from Mexico city and the hate of the Texians. War was averted thanks to the Emperor's successful diplomatic maneuvers, but Ruiz was retained in the frontier, and given command of the army there, one of the youngest generals of the Empire. This earned the jealousy of many, such as General Gabriel Valencia. On the other hand, he forged friendships with men such as Augusto Noble, who would later become the commander of the Indian Cavalry.

Though his family wanted Ruiz to get involved in politics, he refused, feeling more comfortable as a military man than a statesman. He married the daughter of a Member of Parliament for the National Patriotic Party in 1847, but reportedly did not discuss politics with her. He remained rather apolitical, though he was a firm nationalist and an enthusiastic monarchist. In his personal life, Ruiz was known for portraying an image of a secure, affable and brave man, but internally he often questioned and second-guessed himself. At times, he seemed to suffer from crippling depression. The loving relation he developed with his wife, Doña Camila Sierra de Ruiz, helped him. He was, however, an aloof and demanding father, seemingly because he wanted to make sure his children would be able to fend for themselves. He was similar in his relations with his men, being prone to launching into motivational speeches but also demanding and enforcing strict discipline. The men loved him for the most part, finding him fair and unpretentious. Though he enjoyed the battles at first, the bloody war would change his opinion as the casualties mounted. And even if he hated to be harsh with civilians, he was ruthless in his dealings with guerrillas. Many have also noticed great apathy on his part towards the slaves and indigenous soldiers, though he always treated them with dignity and respect. He definitely shared the prejudices of his era.

When the Mexican-American war started, Ruiz rose to prominence as the commander of the army closest to the frontier. He was supposed to simply delay the Americans, but he turned them back at San Jacinto and invaded Louisiana. He was subsequently promoted and given command of all Mexican troops in the area. His successful campaign, called the Eagles Offensive, would give him fame and recognition, though he seemingly didn't crave either. "Lighting Ruiz" as he came to be known, would defeat Taylor and take New Orleans, starting a year of military occupation, during which his anxiety and depression only grew as he found himself outside of his element, and this reflected on his skills as a commander. He had special trouble coordinating with his lieutenants, especially Valencia. In the Battles of Avoyelles, he dithered and held off reinforcements even as Valencia fought tooth and nail against the Americans. He paid dearly for the mistake. A sharpshooter's bullet would end the life of the Marshal during the battle at Breaux Bridge. Ruiz left behind a legacy as one of Mexico's greatest military heroes, but one of the most hated foes of the United States as well, being seen as a butcher and a tyrant - to this day, many refer to him as "King Lewis" and talk of the atrocities of the Mexican occupation of Louisiana. His army was taken over by Valencia, who was never able to instill the same pride and loyalty as Ruiz did. History would make many forget his flaws, and the government of Salazar often used his image as a rallying point. His widow, two sons and a daughter survived him, and although they formed a personal friendship with Marshal Salazar, who offered a sizable pension, they stayed off the public scene.

"The horrible privations of war should teach us to appreciate peace, to grant forgiveness, and to toil for prosperity."

Mexican general and statesman, hailed as the Hero of Veracruz for his successful defense of the Port City during the Mexican-American War. Born into a poor family in Puebla, in March 23, 1803, Salazar was always attracted to military life, watching the militias drill around the city square. He stayed out of the first chaotic stages of struggle for Independence, but joined the army as a drummer boy in 1816 when Agustin I formed the Trigarante Army, which instilled in him a lifelong loyalty to the monarchy and to order. Two years later, he had obtained a command as a lieutenant due to his sheer talent and bravery. After the war, he enlisted in the National College and obtained the education he had lacked. Appointed a commander, he earned the affections of his superior officer, who helped him rise through the ranks. Yet, Salazar’s conflictive aptitude, his low birth and poor economic status, and his frequent insubordination stalled his career. When his superior officer retired, the higher ups decided to get rid of the problematic colonel and appointed him to the Army of Central America, which was seen as an army of cutthroats and thieves. Salazar turned things around and instilled pride and discipline in his men, earning their loyalty and admiration. At the same time, he became infamous due to his cruelty and ruthlessness towards the native population.

His status as an officer allowed Salazar to marry with the daughter of an hacendado, something that would usually be off limits for someone from a poor family. The relation was good, even genuinely loving at times. Salazar was, however, a frequent womanizer and liked to drink, though he was never abusive towards his wife or his children. Strict and demanding, Salazar was known for being easy to anger and hard to please, but he also was bright, capable and could even be charismatic and grandiose. He was not afraid of showing attention from time to time, looking at affection as a reward. He also showed extreme loyalty and diligence, which earned the trust and affection of many. The story of how he did not forget his mother and father and did everything to give them a comfortable life after becoming an officer is well known. In any case, Salazar's refusal to engage in empty flattery and his non-aristocratic manner stopped his military career. Had it not been for the war, he may have languished in obscurity.

When the war came, Salazar and his army were transferred from Central America to the frontlines at Veracruz. By the time he arrived, the situation had turned desperate. General Veintimilla, who assumed command after the death of Zapatero, proved unsuited to the task at hand. After his nervous collapse, Salazar assumed command and drove back the Americans with the famous war cry of "No gringo shall set a foot in Agustin I's Plaza!" As a general, Salazar was a capable administrator, and his personality attracted the loyalty of his lieutenants, men of difficult personalities that Salazar managed to nonetheless balance effectively. He suffered enormously due to the sight of horrible tragedy that struck Veracruz, which manifested itself in an undying hatred for the US. He seems to have developed a firm belief that he was the chosen instrument of God for the salvation of Mexico, even if he was not particularly religious before the war, and would not become a devout believer even after it. He finally managed to force the surrender of Patterson, giving him the title of the Hero of Veracruz and the national fame and glory that he had so desperately wanted even from his days as a drummer boy. Afterwards, Salazar joined the conspiration known as the Plan of Veracruz, which wanted to overthrow parliament to assure a successful prosecution of the war without the weight of petty politics dragging them down. Not a friend of direct democracy, Salazar was not a tyrant either, and he favored constitutional, limited government. Yet the experience in Veracruz and the fight between Parliament and Empress Louise convinced him that Parliament had to be out of the way for Mexico to be saved. He led the coup and installed himself as President of the Regency Council under Princess Isabel. After the war, he restored Parliament and obtained a seat from Mexico city, and continued as Head of Government as Prime Minister.

"Let us work together, for we can only achieve an united and prosperous Mexico when the people are educated and laborious."

Eldest daughter of Emperor Agustin II and Empress consort Louise, and Princess Regent of Mexico for her brother the Emperor Carlos I. Born in July 28th, 1833 in Mexico City, Princess Isabel grew in the peaceful and prosperous later half of her grandfather's reign. She was known for being an independent and sweet girl, who preferred to run around playing instead of learning etiquette. Her grandfather adored her, and nicknamed her "Little Flower." As she grew up, she learned to be more disciplined. She especially discovered a love for literature, importing several European books and learning English and French. She also developed an appreciation for politics, though according to Agustin II she was remarkably naïve, thinking that all nations always had the best interests of their peoples in mind. Her curiosity pushed her towards travelling her Empire instead of remaining in the palace. To her father's dismay, she often liked to talk to commoners and even tried street food once.

Her aptitude earned the appreciation of the people of Mexico city, and soon enough she was declared the "Fairest Flower of Mexico". Her independent spirit still remained within her, and she sought to have a voice in the nation's politics. For example, she befriended her father's personal friend, Eduardo Castillo, then a simple Member of Parliament but later the leader of Mexico during the war. She also travelled to various points of the Empire, though her father forbade her from leaving the country barring a brief sojourn in the Colombian Caribbean. She was the Heir Presumptive until the birth of her brother Carlos Augusto in 1842, and as such received a complete education. But she was always more interested in the human aspect, and she led several social programs in favor of the poor and needy, which only increased her popularity.

At the start of the war she did what was expected of her - help in galas and other reunions in the palace as a hostess. But when the Battle of Veracruz started, she went against her father's wishes to the front and served as a nurse of the 3M, directly helping several poor soldiers. She met Marshal Salazar there, a man with whom she would establish a fatherly bond. When her father died, a political struggle started because her mother wanted to establish herself as regent against the wishes of Parliament. Her relation with her overwhelming mother had always been tense, and it broke as a result of the crisis. She accepted to form part of Salazar's Plan of Veracruz, and was installed as regent. She largely referred to Salazar's genius as an administrator and politician, but she did push for several laws in favor of the needy of Mexico. Her personal diary is a good account of the Mexican-American War, and it also shows her genuine pain at the suffering of her people.

Last edited:

/arc-anglerfish-arc2-prod-gruponacion.s3.amazonaws.com/public/E7U6XHWRKZC7BNE6P5G474BUNI.jpg)