I’ve read an earlier romance named《法兰西之花》les fleurs de la france, whose acceptance if the “medieval people loathed bathing” myth was quite funny.

Seems like a for-fun piece. The one I referenced is actually more serious.

I’ve read an earlier romance named《法兰西之花》les fleurs de la france, whose acceptance if the “medieval people loathed bathing” myth was quite funny.

Ninety percent of the Chinese ISOT web novels out there consisted of land reforms and confiscating land from the ‘leeches’ who oppresses the peasantry.

Recently,most of the novels set during the late Qing Dynasty and ROC have been entirely purged by qidian's administration,probably at the instigation of the CCP,so few people's writing about that subject anymore.I think the problem with many of these novels was that they weren’t even willing to entertain the idea that Chinese history could have had another “way out”, other than the communist one.

The most notorious one is “Dawn at Lingao”临高启明, which had a colonial attitude against their fellow Chinese people. (although the technological details were quite good. Which brave man can translate it into English?)

But then, anti-communist authors who wanted to pre-empt communism often fell victim to this site’s “pull a Meiji” plague. They assume China had the same social conditions as Japan had.

Recently,most of the novels set during the late Qing Dynasty and ROC have been entirely purged by qidian's administration,probably at the instigation of the CCP,so few people's writing about that subject anymore.

But I do understand what you meant by colonial attitude. In some of the crappier novels, time travelers treated down-timers as nothing more than downtrodden who needed to be 'guided'.

So far,I’ve read two novels set in the Jin Dynasty that avoids the land reforms and the colonial attitude.In two of those novels,the protagonists actually try and compromise with the native nobles(which is essentially what down timers are called in China).

When I first started to read on Qidian in 2015,there were still plenty of novels set in the period,they are now mostly gone.A lot of novels were purged for interfering with cultural harmony(being anti-Manchu) or for preventing the rise of the CCP.Recently? I thought the great book ban on Qidian was around 2015?

Actually 临高启明 has a pretty smart de-centralized writing protocol, and its depiction of the uptimer group (referred to as "500 good-for-nothings" or "d*cks/A-holes/粗胚") show a rather self-teasing tendency of writing.

When I first started to read on Qidian in 2015,there were still plenty of novels set in the period,they are now mostly gone.A lot of novels were purged for interfering with cultural harmony(being anti-Manchu) or for preventing the rise of the CCP.

Sometimes this affects even novels set in the Song or Ming Dynasty. 银狐, which was about a guy setting up his own Chinese state in the Tarim Basin during the Song Dynasty was forced to end prematurely because the authorities doesn’t want him to write about fighting Muslims any more in Central Asia while 漢兒不為奴,which was definitely written by a Huanghan was prematurely ended before banned altogether because of how gruesome it was(the Manchu race was more or less wiped out at the end,but the author just wrote that in the epilogue because he was forced to end quickly).

I think one of the most ironic things about the people in Qidian is that they praise Mao Zedong and see his actions as necessary,even though the current prosperity in China was brought along by Deng bring in capitalism. KMT was just thoroughly demonised despite the CCP being highly similar to it.

I still think that the KMT under Chiang Kai Shek,while corrupt,was still a far nicer place than Mao Zedong’s ‘new China’. One could say that the current China is just as corrupt,it's just that circumstances in Chiang's time(WWII) prevented ROC from reaching its' full potential.I guess most people in China don’t actually know about the massive starvations under Mao Zedong? I honestly don't know if most people honestly don't know,or if the Mao supporters were just the vocal minority(with the vast majority of people not willing to speak out).It’s almost as though people saw him as a flawless man incapable of making any wrong decisions.Even Chinese people well versed in history seems to idolize him.I've been on Qidian for 10 years now and I think there was a large-scale ban around 2014 or 2015.

There is a time and place for everything. Saving people's a*ses from a hell of wars and getting them rich require different skillsets. Unfortunately the KMT's skillset seems to only work fine in the second stage (why eat the first bun if you are full on the third?), on a limited scale, and also required an elimination of conflict of interests (land reform was carried out in Taiwan but barely on the Mainland).

That's still an oversimplification as the difference between capitalism and capitalism can be larger than capitalism and socialism. The capitalisms of Chiang I and Chiang II for example showed stark disparities.

Also it would not be very ironic if you received the same education as they did. The Mao-Deng conflicts are rarely known (but not censored), and basically the official narrative since Deng has been to uphold of Mao's (earlier) achievements, yet emphasize the need to adapt (so again, there's a time and place for everything). It's not strange at all for a Chinese to praise both Mao and Deng.

Fully agree. One of the worst novels I've read had China create a full fledged Japanese-style colonial empire of their own while constantly fighting the Japanese and allied to Nazi Germany for quite some time before fighting them for global supremacy.What would be ironic is the love of some for Nazi Germany (or German/other European jingoism) but strong distaste for Fascist Japan. Ironic as it is though, I've also found Americans/British/etc. to similarly denounce Nazis while sharing the Japanese "net right-wing" view on the evil Chinese and ungrateful Koreans. So ultimately it comes down to where one's butt sits.

I still think that the KMT under Chiang Kai Shek,while corrupt,was still a far nicer place than Mao Zedong’s ‘new China’. I guess most people in China don’t actually know about the massive starvations under Mao Zedong?It’s almost as though people saw him as a flawless man incapable of making any wrong decisions.Even Chinese people well versed in history seems to idolize him.

Thing is that Chiang and KMT,as you mentioned,hardly ruled the majority of China,and in less than ten years after unifying large parts of China,the Japanese invaded. I don't think Chiang or the KMT really had sufficient time to fully pacify the warlords and bring economic prosperity.A lot of Chinese rulers(e.g. Cao Cao) took far longer and never did unify China to the extent the KMT did.It's hardly Chiang's fault that there were a lot of dead people between the late Qing Dynasty and the early 1950s.I did a good number of searches on the web on this subject in Chinese,and a lot of that turned out in Taiwanese or HK websites only. Numbers were most certainly up for debate,but Mao's tenure shows that he was not very astute as an administrator,and most of his grandiose projects ended up backfiring badly.Say what you may about Chiang,but I honestly don't think that Mao would have done a better job handling WWII if he was in Chiang's shoes.I'm not sure how you got the idea because you seem to be able to read Chinese. People know about the Great Famine, but they generally don't believe the numbers widely accepted in foreign countries (you get almost none believing in anything bigger than 30 million - and only very serious anti-CPC people would go by 30 million - my personal take is ~10 or 15 million).

My idea is two-fold:

1. The population was basically the same from late Qing to the early 1950s. So it shows more died under Chiang's watch (or you could argue he didn't get to rule all of them which could in turn interpreted by Mao-loyalists as incompetence) than Mao's.

That is most certainly a fair point,but I don't think purging the capitalists in the country or forcing(sometimes killing) intellectuals to flee is a pretty good idea for industrialization. At any rate,this is the reason why industrialisation shouldn’t be quick.2. Industrialization is a painful process. If a country pushes for it demanding rather timely output without sufficient foreign aid (in the case of South Korea and Taiwan), the agriculture sector has to be sacrificed and you get people starved to death. The catch is again to get certain things from the outside world and colonies (or shared market, etc.) would come in handy in this scenario. When you try to (or are forced to) go fully independent, there's the price.

My grandparents had a similar experience,and after the experience,they were thoroughly anti-Mao. This experience only intensified after they went to HK.They were so terrified by the news that HK was returning China that they fled here to Australia.My late grandma was one of the many that fled a province that was probably hit the hardest by 1959. She was illiterate and I don't think she was in any significant way anti-Mao despite losing a son she brought with her on the way (likely abducted). For all she cared (as it seemed to me) famines were usual, and running away from famines was also usual. It wasn't the first time that she fled where she lived (it's called 跑反).

What should I actually type to search for these comments?Quite often,the only ones I see are the ones that quickly get downvoted. People generally had to use euphemisms like 太祖 when actually refering to Mao Zedong.I get the impression that people don‘t want to get in trouble.Also there are a lot who are vehemently against Mao. I suspect there are more than at least 10 million just by the amount of their comments I see online.

A lot of novels were purged for interfering with cultural harmony(being anti-Manchu) or for preventing the rise of the CCP.

I don’t advocate for the genocide of Manchus,but to be fair,in the context of the novels,I don’t think it would have been plausible for that not to happen.In a lot of the novels,the Manchus have already overrun a large part of China and would have already killed a vast number of Chinese people.Even if the protagonist of such novels tried to prevent a genocide of the Manchus,I don’t think their subordinates would have listened in the event that the Manchus were totally defeated,given the mindset of the 17th century Chinese.This is especially since most of the Manchu male population would have been warriors who participated in the war. Their defeat would have been so severe that a lot of the male population would have been completely killed even if Ming forces didn‘t finish them off.I most certainly think that it’s possible for the Manchu population to survive in novels set pre-1644 however.The problem with post 1644 novels was that a lot of Manchus and their families moved into China,and would have been highly vulnerable should their armies be defeated.To be frank:

Hate-mongerrors who advocate for genocide against a law-abiding ethnic group who did wrong a few centuries ago just to gain a few more clicks deserve much more than a ban.

Germany wasn’t (much) involved in the scramble for China, which was part of the reason for their sympathy.What would be ironic is the love of some for Nazi Germany (or German/other European jingoism) but strong distaste for Fascist Japan.

Yes,I think we should open up another threat in non-politics if we want to discuss any further.Isn't the thread nearly turned into a discussion forum for Chinese novels. Not like it's bad and all, isn't this kinda straying away from the topic?

Sorry if I sound bit of a nuisance. I just can't helped myself noticed the trend.

As for the matter regarding time-travelling novels, Chinese politics and ethnicity, I've come across some nasty comments on the internet by people in regards to Manchus and other nomadic dynasties. Let's just say the comments goes along the vein of 'Han nationalism' and 'Han supremacism', believe it or not. :x

Now that I've written close to 30 pieces, I feel I'd be tormenting all my readers if there's still not a convenient catalog.

Every one of them is not just what the title suggests it is,

the settings are all mixed together, and expressed here and there.

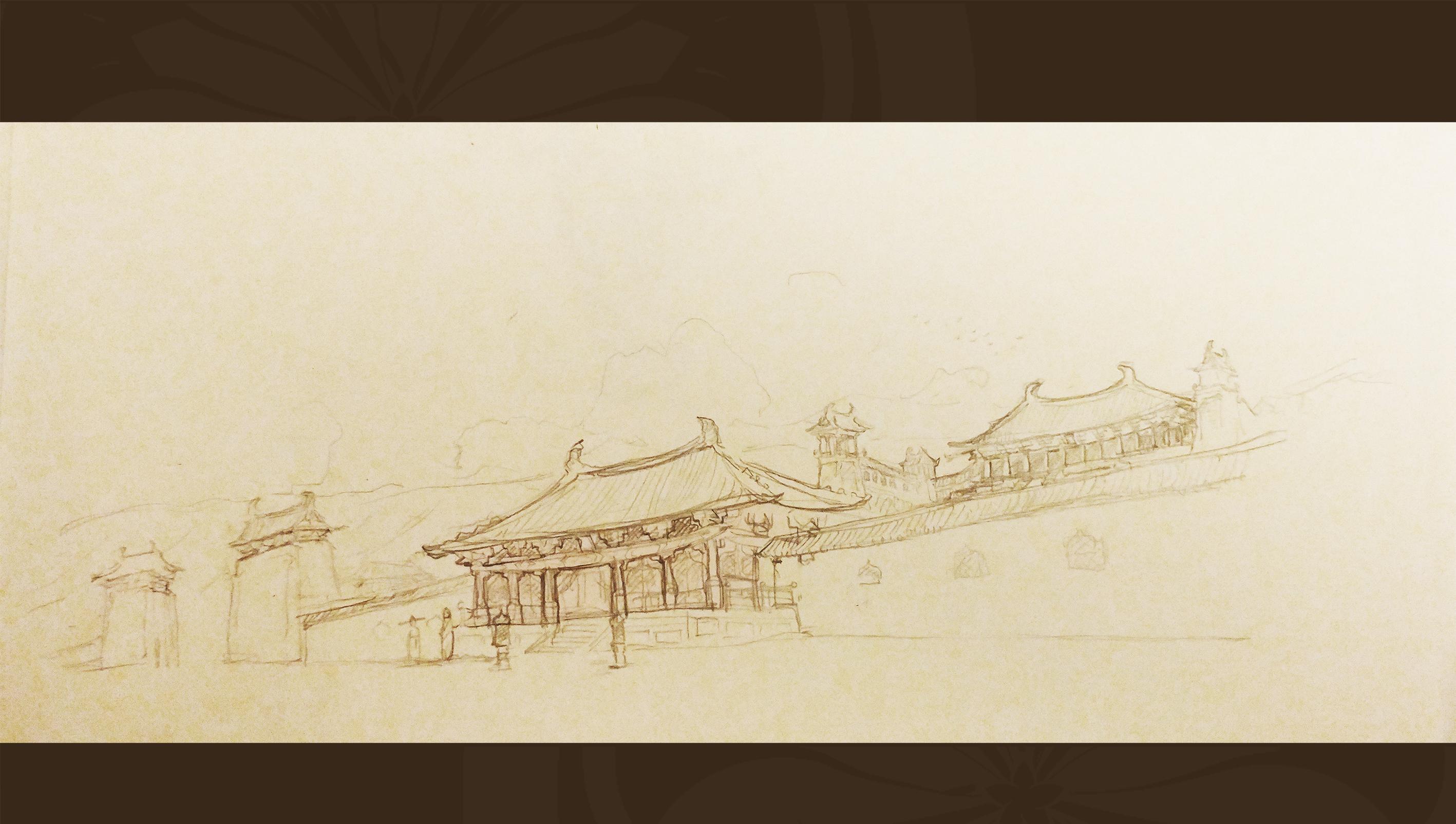

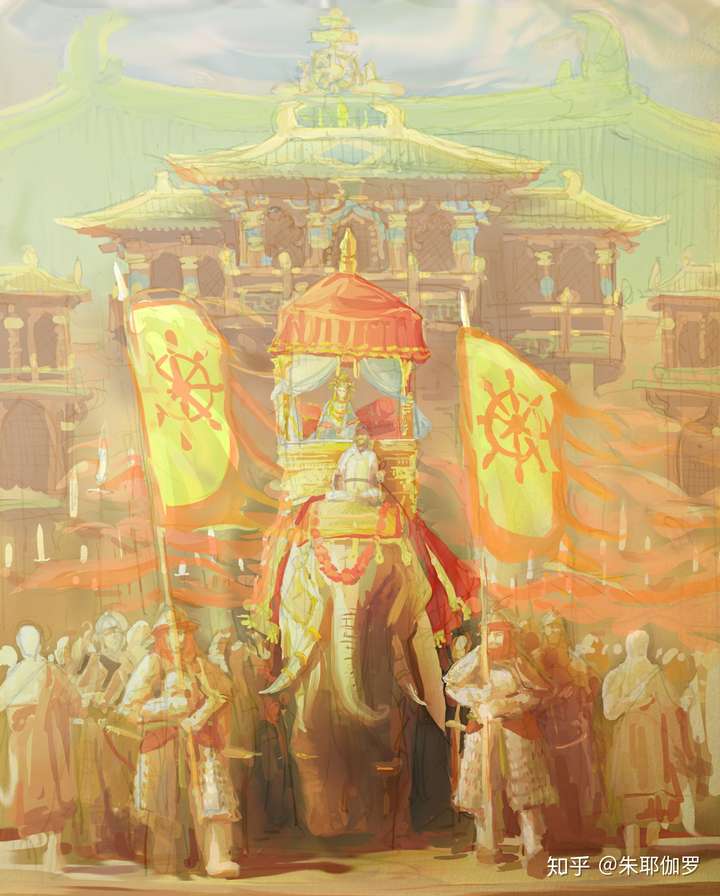

Zhaode Gate of the Central Capital, scene of a princess' wedding, ~1350