Minor note: the name of the shul/synagogue is weird; I'd suggest naming it something like "X synagogue"(where x is the name of the sponsor/benefactor). And the design is a bit weird; historically there isn't a consistent "synagogue" architecture" until about 1830 or so OTL and previously the general rule is that it more or less follows whatever the local taste or custom. Otherwise a cool building update-I like that you based the mosque on I suppose the Friday mosque of Varamin/Congregational mosque of Yazd and the Maydan of Isfahan.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Mahakhitan: A Chinese Buddhist Civilization in India

- Thread starter Green Painting

- Start date

-

- Tags

- architecture india khitans pictures

Threadmarks

View all 51 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 27 Mahakhitan Kaleidoscope (1): A Brief Introduction to the Empire’s Administrative Branch in 18th Century Chapter 28 Mahakhitan Kaleidoscope (2): Mahakhitan Vexillology, and Brief Introduction to the Country’s Army and Navy Bonus 006: Dimensions of the South Asian Subcontinent, Among Other Things Chapter 29 Stories of Mahakhitan Porcelain Art (Part One) Bonus 008: Preview of the Mahakhitan State mod For Victoria II. Original Historical Material: The Mahakhitan Chronicle (1632-1760) Chapter 30 Stories of Mahakhitan Porcelain Art (Part Two) Chapter 040, An Illustrated Guide to South City Wards.Minor note: the name of the shul/synagogue is weird; I'd suggest naming it something like "X synagogue"(where x is the name of the sponsor/benefactor). And the design is a bit weird; historically there isn't a consistent "synagogue" architecture" until about 1830 or so OTL and previously the general rule is that it more or less follows whatever the local taste or custom.

Updated. I didn't realize it was about Chapter 20 because I had no idea of the specific words "shul" and "synagogue"

NP. Note that depending on the size of the community there may be smaller neighborhood/local synagogues or shuls. E.g. there's the main shul but there might be a smaller one founded by a specific merchant community or guild or one that serves a small neighborhood area that isn't really convenient to the main shul.

Hey guys. Chapter 22 is almost finished, but there're issues to be clarified about which I have messaged Kara.

Chapter 22 Wild Vines Entangling on the Desolate Tomb*: The Empress and Her Mahakhitan Southern Capital Palaces (Part 2)

Chapter 22 Wild Vines Entangling on the Desolate Tomb*: The Empress and Her Mahakhitan Southern Capital Palaces (Part 2)

022 – 蘞蔓於野:女皇和她的摩訶契丹南京宮闕(下)

*Originally as a line from Creeping Vine (Ge Sheng), Odes of Tang, Classics of Poetry (詩經・唐風・葛生).

Picking up from the last chapter, the stories of the empress’ entire life are fully intertwined with this building complex, so we are forced to tell them together.

I finished planning for this series in Feburary, and today … it’s finally done (the update was in June), phew.

/////

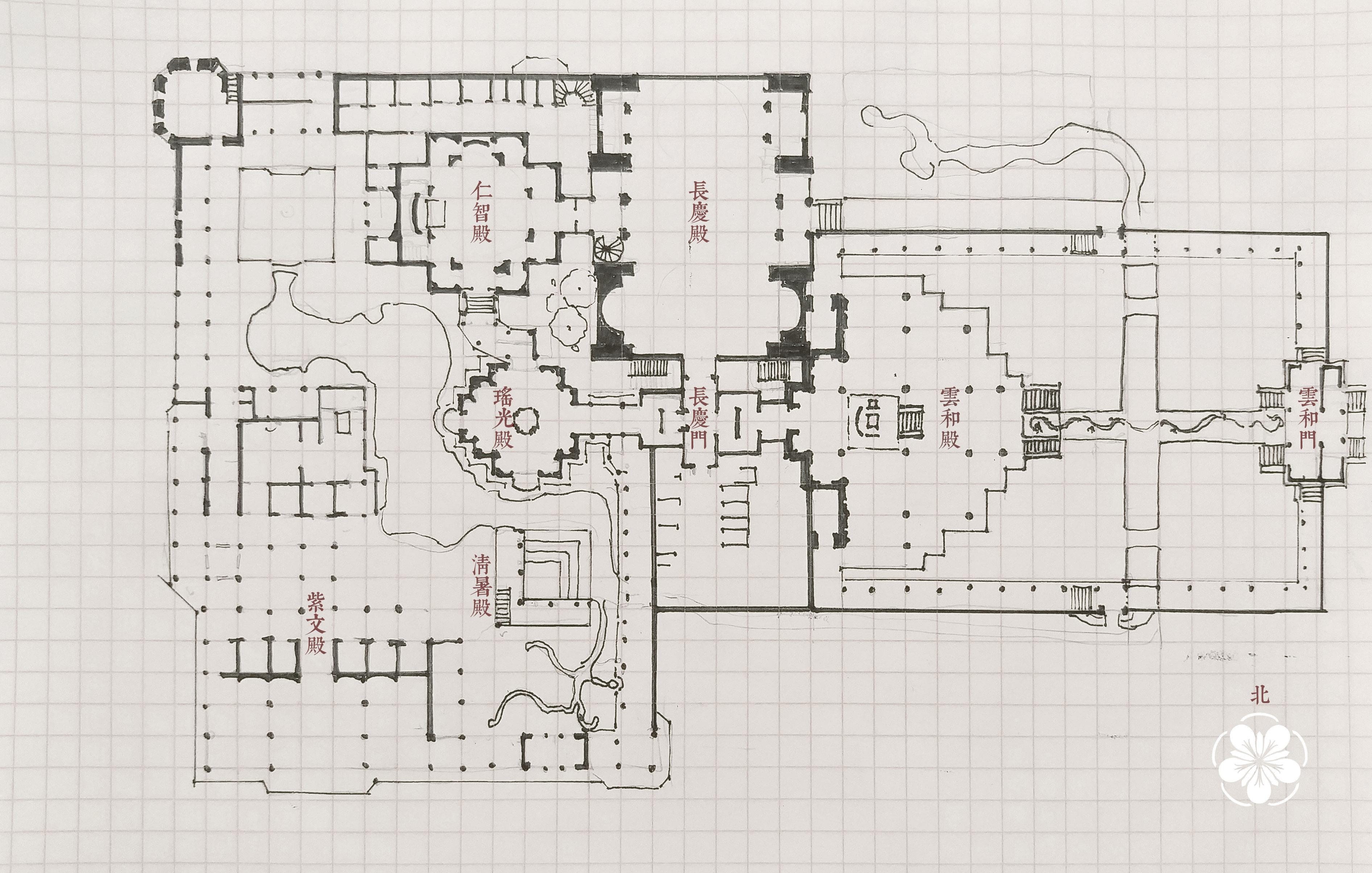

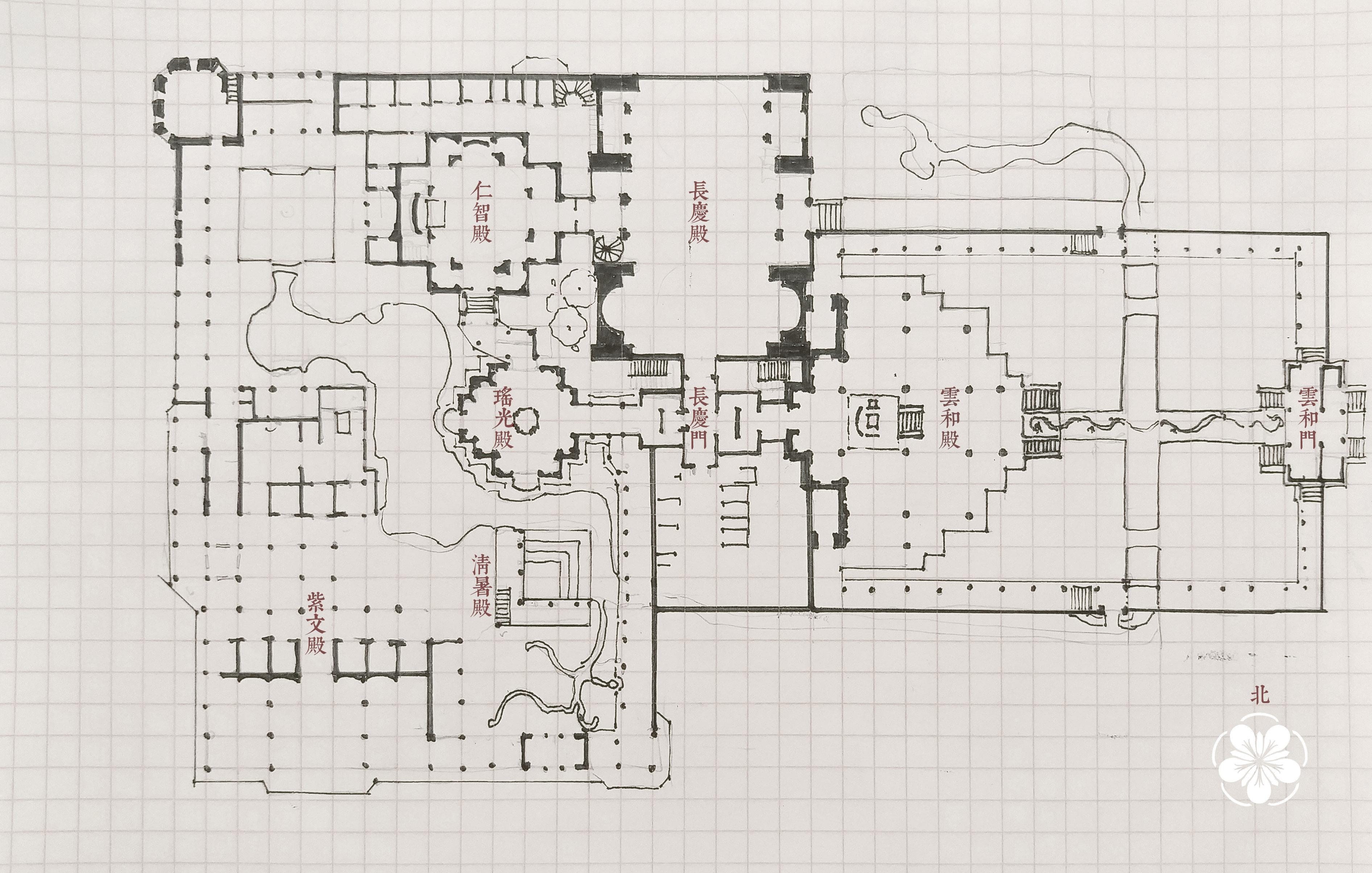

As most of the documents and designs in the Ministry of Works were lost and/or destroyed in the second siege of the Central Capital (tears), the floorplan attached here came from the depiction of the civilians from the Southern Capital, so the complete authenticity of it cannot be guaranteed …

Translated floorplan is too big to be uploaded; link:

https://mega.nz/#!Z9QCWKIL!_heyG3P2pqLmg7VVJtYOsQ8D3iRh2gVseJLx-JA_e2E

---------------------------------------------------------------

… …

Speaking of the largest among the Southern Capital palaces, Changqing Hall (長慶殿, lit. “Lasting Celebration Hall”) is the sole candidate.

The function of Changqing Hall is similar to that of the Yuanqing Hall (元慶殿) of the Central Capital palaces, as an enormous whole-brick structure serving as the emperor’s banquet hall. As we walk through the Changqing Gate, turn right and proceed to the north, we realise as we enter the hall that it is by no means comparable to Yuanqing Hall which was built two hundred years earlier.

The design of the hall completely abandoned the successive and bulky single arches that were featured in early Mahakhitan brick-stone buildings. Yuanqing Hall of the Central Capital back then, despite gigantic in size, was monotonal and dark within with poor ventilation. During joyful feasts, even slightly more lights would make the air stale, so the Khitan emperors gradually began to dislike it.

With the assistance of designers from Constantinople and craftsmen from Isfahan this time, the issues of ventilation and lighting were solved with the light dome and pendentive. No other hall or palace in Mahakhitan ever had such a bright inner space before, as the subjects attending imperial banquets exclaimed at the enormous half-circle windows and delicate windowpane patterns, as well as seeing the roofs of the three rooms of the hall as if they were floating in the air in daylight. After visiting the empress, the envoy from Constantinople also wrote in his letter(s) that such an experience used to only be available in one other place.

As the sun set towards the west, when the second dish of the Khitan feast was being brought to the hall, the palace servants would light up the chandeliers. The stars painted on the three domes would glitter like real celestial objects, and the waving glow of the flare would gently push the tapestries and curtains around as if giving life to the ancient Khitan battles woven on these Persian fabrics that were worth a thousand pieces of gold. The empress would probably have her best time seeing these lords and officials flabbergasted in surprise.

Today, although the tapestries and curtains are nowhere to be found, and the inner decorative items in the hall have been long thrown away into a tiny room, several master craftsmen from the Ministry of Works still unanimously agree the hall itself is surprisingly sturdy. Despite having served as a war shelter during the great chaos, the underground water cellars under the halls such as the Changqing Hall almost have their wall decorations and floors completely intact, which should be rather easy to restore.

Of course, I also understand since the reputation of Changqing Hall had long been widely circulated across the nation, this is probably one of the other reasons why people carefully tried to protect it – even back when the empress was still alive, local lords from everywhere already had gala halls and other buildings imitating Changqing Hall in their respective fiefdom capitals – but unfortunately had to downsize due to lack of the secret recipe from Fulin and the rough concrete technology.

It seems this hall indeed impressed everyone very much. Even by now (1563), buildings of large spaces such as Zizheng Halls (諮政堂, lit. “Counseling Policies Hall) in Central and Southern Capitals still bear resemblance to Changqing Hall.

(So much so that the parliamentary buildings and train stations of Mahakhitan in the future will have large halls intentionally following the style of Changqing Hall.)

There is a gate in Changqing Hall towards the west, leading to Renzhi Hall (仁智殿, lit. “Benevolence Wisdom Hall”).

This hall, in turn, was where the empress used to summon her subjects for further discussions and meetings after her daily court assemblies. It also served as the imperial family’s library. The original and translated books the empress gathered were piled on the shelves on the four sides of this square hall. Book-collecting was one of Her Majesty’s obsessive hobbies – she seemed to always had felt inferior due to her lack of formal education since childhood. In Mahakhitan back then, crown princes were subjected to very systematic educational demands, whereas for girls even princesses, reading was by no means necessary.

Her lack of confidence on her own educational background and lack of dedicated training of ruling since she was young made the empress sometimes very reliant on her husband when managing political affairs – although the empress had quite good personal capabilities and had kept reading all her life. She seemed, however, really in need of such sense of security. King Xuan (宣王, where 宣/Xuan1 seems to be the posthumous temple name) of Shanyang, as the crown prince, already had experience of assisting his father when dealing with political and military affairs of the circuit. He played a decisive role in the course of the empress’ consolidation of central power with his own experience as a local lord. Today, no one knows which of those decrees came from Her Majesty herself, and which were drafted by the Shanyang King. (Of course, the absolute loyalty of the troops from Shanyang Circuit as also an important reason why the empire managed to remain relatively stable during all those successes or failures under the empress.)

The Ministry of Works claims in their report that the conditions of Renzhi Hall nowadays are worrying. During the Chongguang (重光, lit. “Re-Brighten”) years when the national treasury was depleted, the previous emperor ordered to remove the gold and bronze tiles from the Southern Capital palaces for coinage and cannon production. After that the brick-structured domes of Renzhi Hall and Yaoguang (瑤光殿, where 瑤光/Yaoguang is the ancient Chinese name for the star Alkaid) Hall has since been entirely exposed in sunlight and wind without tiles covering them. The two domes are already leaking in many places, with the paintings on them long spoiled. The bookshelves are completely rotten, and the books and records missing – the best-case result for them would be to appear in the ancient book market of the Southern Capital Bazaar and to be picked and brought as the foundation of the library collection by lecturers from the Southern Capital Zhongzhi Academy* (種智院) who understand the values of them. As for the worst-case scenario, I’d rather prefer not to speak of it.

*(Note: the Southern Capital Zhongzhi Academy has been, in a long time, the only modern university in Mahakhitan, although during the 16th-17th Centuries many places of the empire had quite a lot ancient theological academies and some Confucian colleges, whose later modernisation shall be saved for future introductions possibly. 種智院/“Planting Wisdom Court”, the Buddhism-influenced name IOTL is actually used by a Japanese university 種智院大学/Shuchiin University)

Going westward along the northern road of the palaces, the bedroom palace of the empress and her husband back then, Ziwen Hall (紫文殿, lit. “Purple Cultured Hall”) is to the south of the long corridor.

We seem to have mentioned that during the fifty years the palaces were not in use, countless craftsmen used to visit the Southern Capital palaces with various methods. Ziwen Hall, on top of anything else, was the main reason why these people were willing to spend a fortune to bribe the guards and sneak into the palaces risking their lives.

After the civil war, the Southern Capital was the first to recover thanks to the trade through the Indian Ocean, and was where some newly rich of the empire gathered to live during the twenty odd years thereafter. The building fashions popular among them were not as rigid and obsessed with rites like in the case of the old aristocrats, so the rebellious – by the standard back then – and incredibly luxurious Southern Capital palaces became their primary reference.

Being suspected of breaking the hierarchy (specifically called 逾製/Yu2 Zhi4 in Chinese) was hardly avoidable, but the grey area between allowed much room for maneuvering. The craftsmen in Southern Capital had ten thousand ways to cleverly bypass the red line. On the other hand, the debilitated imperial family now depended on the support of these upstarts, and released signals of “temporary acquiescence” in many aspects – the silent approval of newly emerged merchant class dressing in exclusively aristocratic patterns and colours during the years of Chongguang should be quite revealing.

Therefore, the new generation of the Liao Southern Capital civilian residential buildings, compared to their grey, humble predecessors, showed a much more obvious “official look”. Known as the “empress style”, it became the symbol of the 16th-17th Centuries Mahakhitan architecture, with its origin traced back to the Ziwen Hall here.

In contrast to the more rigid halls including the Yunhe and the Changqing, the space allocation and dimension of Ziwen Hall are the most user-friendly, and most casually designed as the private space of the imperial family. As a result it has been the most favoured reference among civilians.

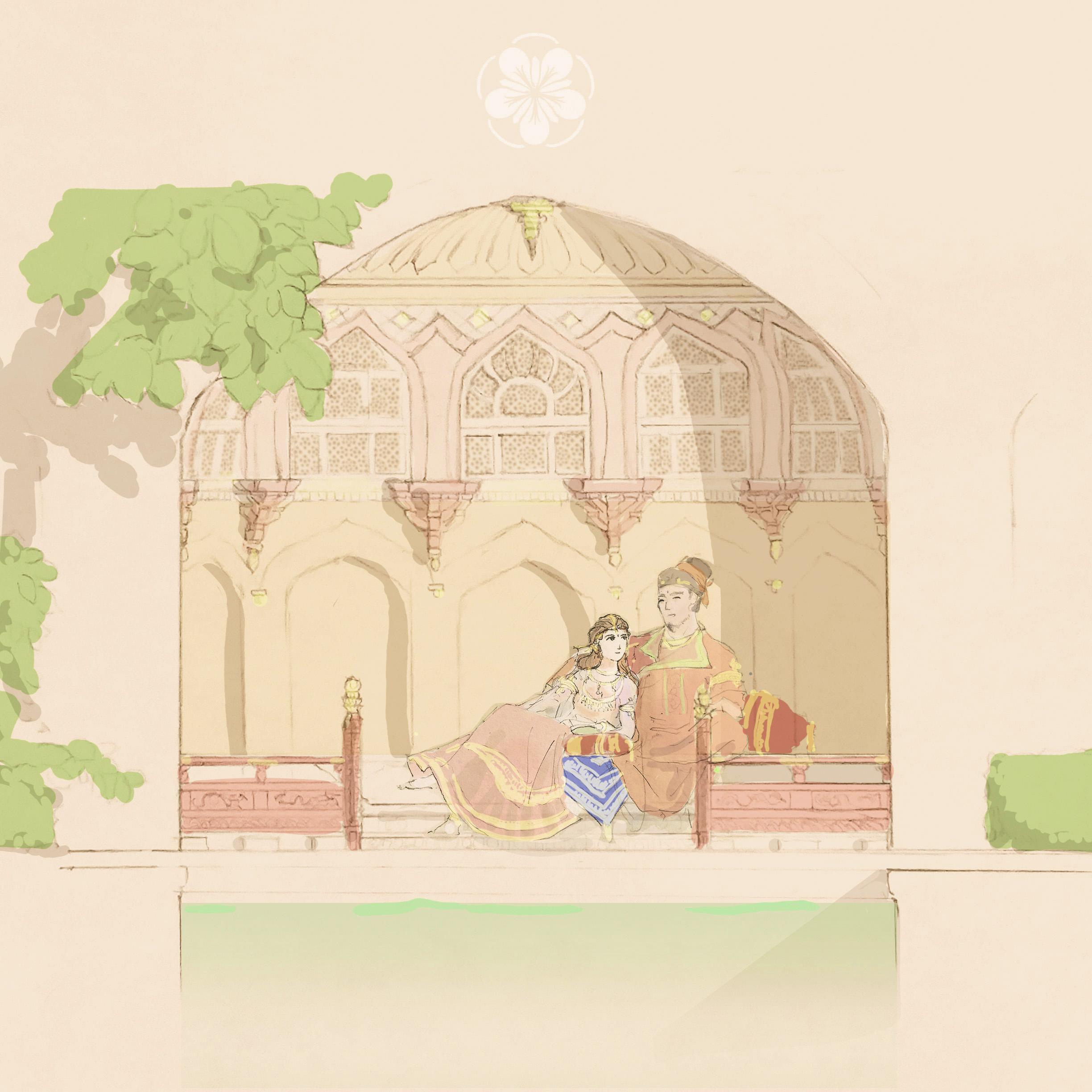

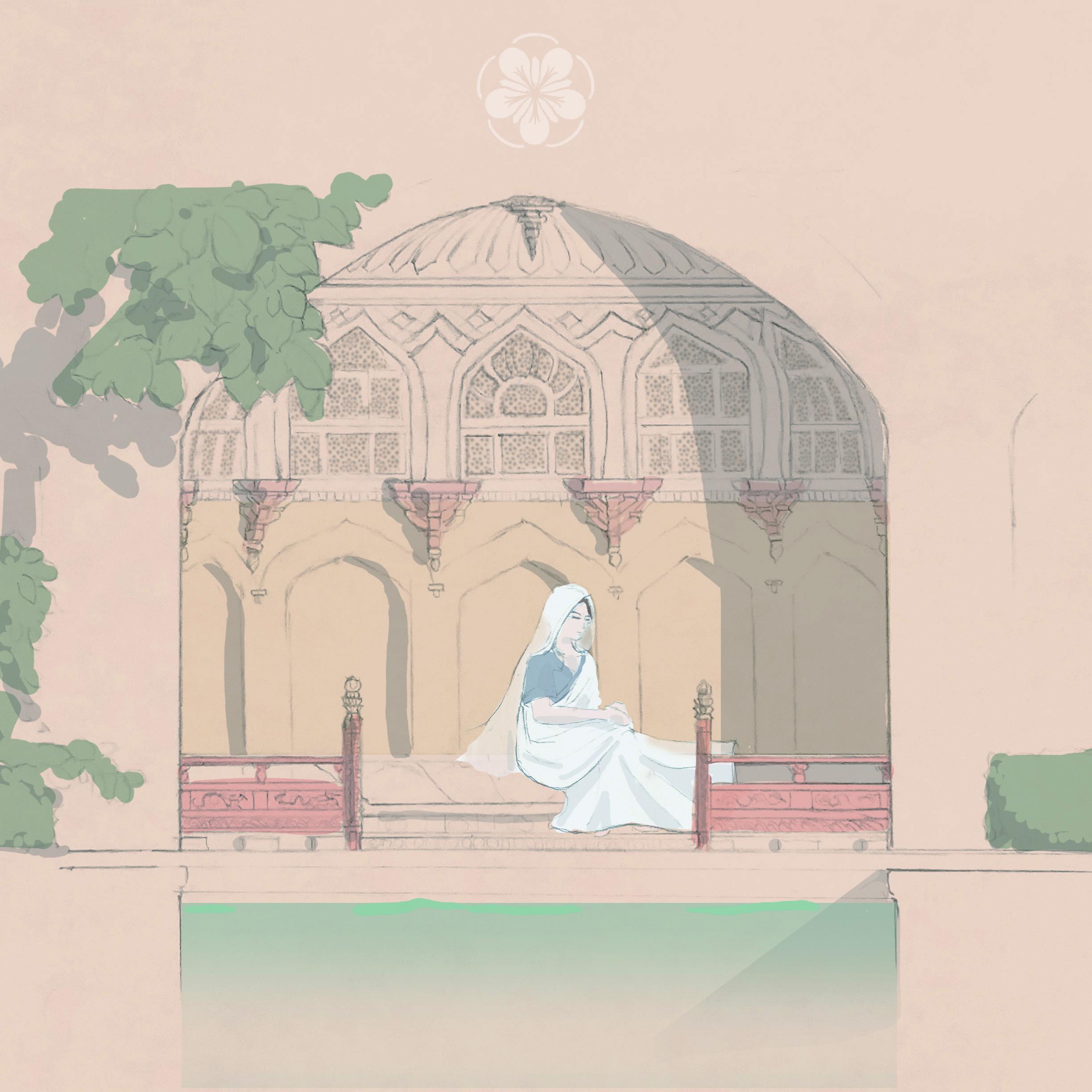

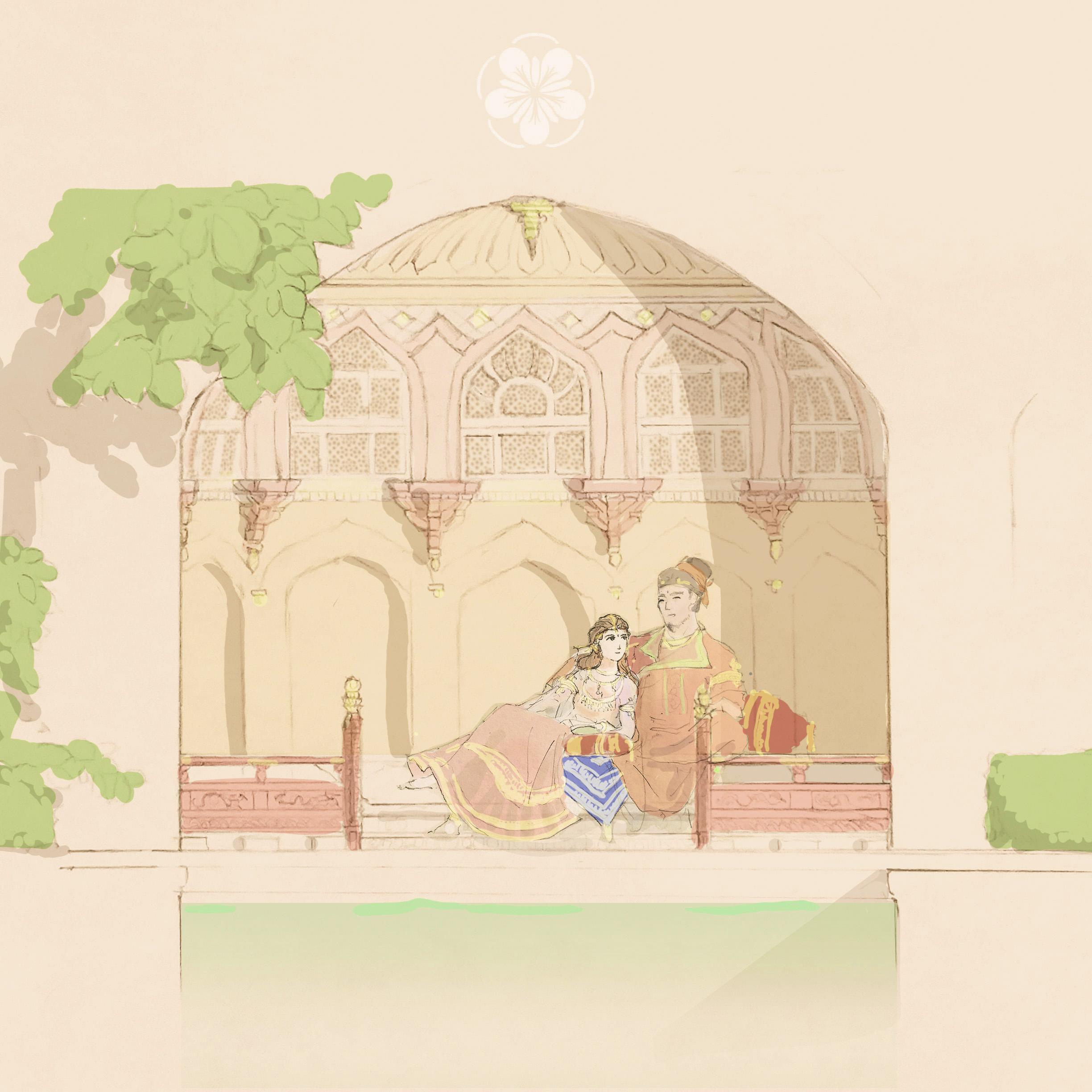

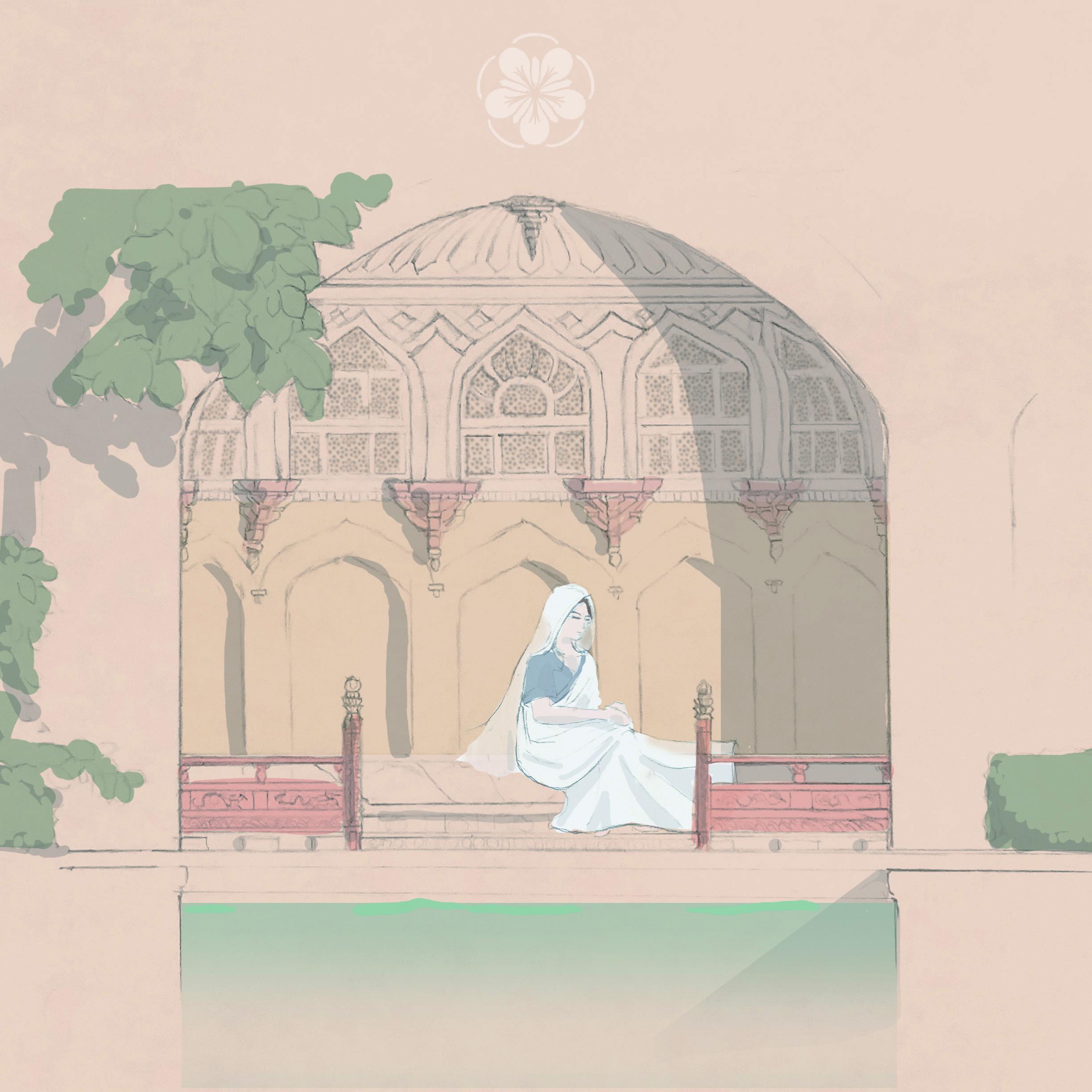

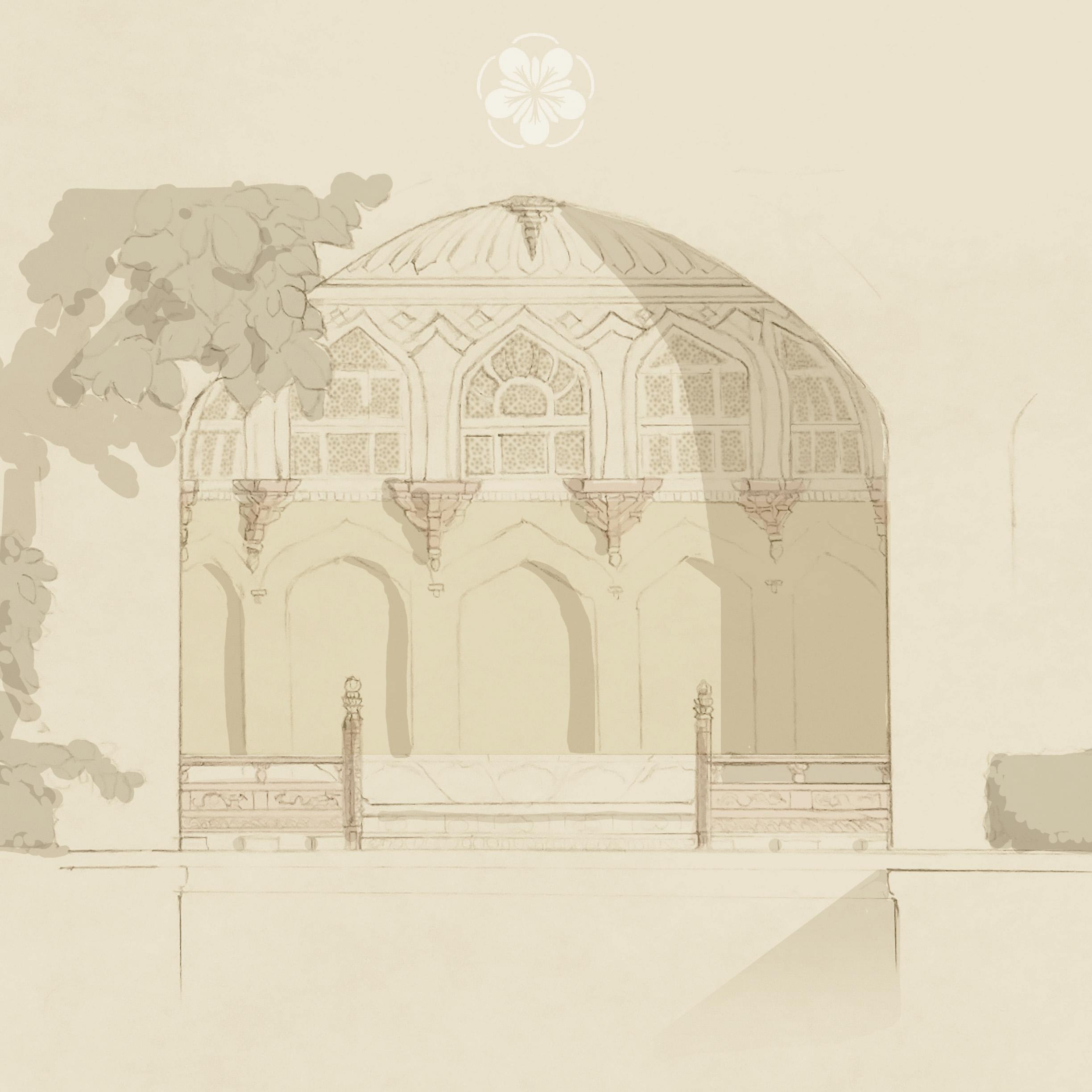

Northern terrace of Ziwen Hall.

This hall mingles all Her Majesty’s favourite elements. The “Water Fringe Lake (荇海子, where /Xing4 refers to Nymphoides peltata, or fringed water lily, or water fringe while 海子/small sea in ancient Chinese often meant lake or pool)” to the north of Ziwen Hall is almost a Persian-style garden. The southern side of the hall is on the other hand the arcade overlooking the entire Indus Delta that bears quite some resemblance to Boukoleon Palace of Constantinople. The Feathers Lake (羽淀, where 羽 means Feather, and 淀 is the traditional local way of calling a water body – lakes or swamps – in northern China) to the east of the hall is on the other hand an open palace garden with an artificial stream. However, at the end of the stream lies a central Sindhu-style stair well, through which water from the surface of the palace garden gather and flow back to the giant reservoir underneath the palaces.

That’s right, following the advice of the hired Fulin craftsmen, in order to level the base and make the palaces visually larger, most of the palace complex is built upon arches, thus forming the gigantic water reservoir under the buildings that helps to cool down the palaces during harsh summers and provides water for landscape and consumption uses.

In the meantime, the consequent underground corridors also have become the transit route for the hundreds of palace servants as well as part of the guardian system, successfully rendering this rather small palace complex not as seemingly crowded in regular days.

Inside the walls of Ziwen Hall there is supposedly a bronze pipe system for the cooling of the walls and roof, but we regrettably cannot personally experience its effect.

It has been said that back then, the empress and the Shanyang King would cuddle together on one of the countless terraces of Ziwen Hall, spending one after another afternoons in the undisturbed shades of trees. The country was rich as it never had been, and the two sons Dun and Jing (both became emperors years later, as Minzong/愍宗 and Pingzong/平宗) and two little daughters growing up day by day. It was as if the happiness of this tiny family would last forever.

King Xuan of Shanyang passed away in March, the 27th Year (of Duanning; 1497), at the age of forty-five.

It was said at the funeral, she put her favourite neckwear on the chest of the Shanyang King. “See the necklace as I am here.” She said.

The empress never wore a single jewelry since then.

Later historians always claimed that since the death of the Shanyang King, some the empress’ policies in her late years appeared to be too radical, and threatened the vested interests of too many classes, thus probably served as the initial trigger of the subsequent turmoil the empire suffered. In her late years, the campaign against Tianfang (1504-1507) was also extremely costly both in expenditures and human lives. Although four years of bitter war was concluded with the final victory, the navy that the state of Liao took pride in almost lost all of its main forces, along with the vessels and talents previously shined in the great voyages. Her appointment of Ü-Tsang monks as officials was also met with resentment from the Liao bureaucrats and monks, whereas the “Tianfang special tax” during her last few years led to grudges of the Southern Capital merchants.

It was even rumoured in the capital, that the empress and her son-in-law, the prince of Ü-Tsang kept an unspeakable relationship. But the empress herself did not seem to have heard anything. Indeed, she was making less and less appearances in front of her court officials, while the palace servants said she was always sitting idly in the imperial Buddhist hall in the Southern Capital palaces – the Yaoguang Hall. No one knew what she had been thinking, and the people’s image of her was undergoing changes.

One day in the 37th Year of Duanning (1507), the empress and the crown prince (the future Minzong Emperor) had a brief argument regarding a certain policy concerning Kangzhou. In Qijuzhu (起居注, lit. “rise and live record”, which was the name of the record of the daily behavior, schedule and words of ancient Chinese emperors) the last segment of their conversation was recorded.

In the record, the empress admitted that without the help of the Shanyang King, she found it hard to grasp a lot of situations. When faced with her son that had issues with her order, she said her time was limited. Therefore she was determined to push reform measures that would provoke the aristocracy to the very end and finish the most costly battles with her own hands, so that when her son inherit the throne, he would be able to show his most merciful side and even abolish some of empress’ “bad policies” so as to win more admiration from his subjects.

The crown prince burst into tears and kneeled for so long without getting up.

*The captions of the three pics above form the last line of the poem Creeping Vine (Ge Sheng) in Odes of Tang, Classics of Poetry. Kara's original captions in Simplified Chinese are left unchanged.

Hm, speaking of one’s destiny, of course it depends on striving by one’s self, but the course of history should be taken into account too.

Also, even the most powerful individual in the world would be as fragile as a child when left all alone.

022 – 蘞蔓於野:女皇和她的摩訶契丹南京宮闕(下)

*Originally as a line from Creeping Vine (Ge Sheng), Odes of Tang, Classics of Poetry (詩經・唐風・葛生).

Picking up from the last chapter, the stories of the empress’ entire life are fully intertwined with this building complex, so we are forced to tell them together.

I finished planning for this series in Feburary, and today … it’s finally done (the update was in June), phew.

/////

As most of the documents and designs in the Ministry of Works were lost and/or destroyed in the second siege of the Central Capital (tears), the floorplan attached here came from the depiction of the civilians from the Southern Capital, so the complete authenticity of it cannot be guaranteed …

Translated floorplan is too big to be uploaded; link:

https://mega.nz/#!Z9QCWKIL!_heyG3P2pqLmg7VVJtYOsQ8D3iRh2gVseJLx-JA_e2E

---------------------------------------------------------------

… …

Speaking of the largest among the Southern Capital palaces, Changqing Hall (長慶殿, lit. “Lasting Celebration Hall”) is the sole candidate.

The function of Changqing Hall is similar to that of the Yuanqing Hall (元慶殿) of the Central Capital palaces, as an enormous whole-brick structure serving as the emperor’s banquet hall. As we walk through the Changqing Gate, turn right and proceed to the north, we realise as we enter the hall that it is by no means comparable to Yuanqing Hall which was built two hundred years earlier.

The design of the hall completely abandoned the successive and bulky single arches that were featured in early Mahakhitan brick-stone buildings. Yuanqing Hall of the Central Capital back then, despite gigantic in size, was monotonal and dark within with poor ventilation. During joyful feasts, even slightly more lights would make the air stale, so the Khitan emperors gradually began to dislike it.

With the assistance of designers from Constantinople and craftsmen from Isfahan this time, the issues of ventilation and lighting were solved with the light dome and pendentive. No other hall or palace in Mahakhitan ever had such a bright inner space before, as the subjects attending imperial banquets exclaimed at the enormous half-circle windows and delicate windowpane patterns, as well as seeing the roofs of the three rooms of the hall as if they were floating in the air in daylight. After visiting the empress, the envoy from Constantinople also wrote in his letter(s) that such an experience used to only be available in one other place.

As the sun set towards the west, when the second dish of the Khitan feast was being brought to the hall, the palace servants would light up the chandeliers. The stars painted on the three domes would glitter like real celestial objects, and the waving glow of the flare would gently push the tapestries and curtains around as if giving life to the ancient Khitan battles woven on these Persian fabrics that were worth a thousand pieces of gold. The empress would probably have her best time seeing these lords and officials flabbergasted in surprise.

Today, although the tapestries and curtains are nowhere to be found, and the inner decorative items in the hall have been long thrown away into a tiny room, several master craftsmen from the Ministry of Works still unanimously agree the hall itself is surprisingly sturdy. Despite having served as a war shelter during the great chaos, the underground water cellars under the halls such as the Changqing Hall almost have their wall decorations and floors completely intact, which should be rather easy to restore.

Of course, I also understand since the reputation of Changqing Hall had long been widely circulated across the nation, this is probably one of the other reasons why people carefully tried to protect it – even back when the empress was still alive, local lords from everywhere already had gala halls and other buildings imitating Changqing Hall in their respective fiefdom capitals – but unfortunately had to downsize due to lack of the secret recipe from Fulin and the rough concrete technology.

It seems this hall indeed impressed everyone very much. Even by now (1563), buildings of large spaces such as Zizheng Halls (諮政堂, lit. “Counseling Policies Hall) in Central and Southern Capitals still bear resemblance to Changqing Hall.

(So much so that the parliamentary buildings and train stations of Mahakhitan in the future will have large halls intentionally following the style of Changqing Hall.)

------------------------------------------------------------------

There is a gate in Changqing Hall towards the west, leading to Renzhi Hall (仁智殿, lit. “Benevolence Wisdom Hall”).

This hall, in turn, was where the empress used to summon her subjects for further discussions and meetings after her daily court assemblies. It also served as the imperial family’s library. The original and translated books the empress gathered were piled on the shelves on the four sides of this square hall. Book-collecting was one of Her Majesty’s obsessive hobbies – she seemed to always had felt inferior due to her lack of formal education since childhood. In Mahakhitan back then, crown princes were subjected to very systematic educational demands, whereas for girls even princesses, reading was by no means necessary.

Her lack of confidence on her own educational background and lack of dedicated training of ruling since she was young made the empress sometimes very reliant on her husband when managing political affairs – although the empress had quite good personal capabilities and had kept reading all her life. She seemed, however, really in need of such sense of security. King Xuan (宣王, where 宣/Xuan1 seems to be the posthumous temple name) of Shanyang, as the crown prince, already had experience of assisting his father when dealing with political and military affairs of the circuit. He played a decisive role in the course of the empress’ consolidation of central power with his own experience as a local lord. Today, no one knows which of those decrees came from Her Majesty herself, and which were drafted by the Shanyang King. (Of course, the absolute loyalty of the troops from Shanyang Circuit as also an important reason why the empire managed to remain relatively stable during all those successes or failures under the empress.)

The Ministry of Works claims in their report that the conditions of Renzhi Hall nowadays are worrying. During the Chongguang (重光, lit. “Re-Brighten”) years when the national treasury was depleted, the previous emperor ordered to remove the gold and bronze tiles from the Southern Capital palaces for coinage and cannon production. After that the brick-structured domes of Renzhi Hall and Yaoguang (瑤光殿, where 瑤光/Yaoguang is the ancient Chinese name for the star Alkaid) Hall has since been entirely exposed in sunlight and wind without tiles covering them. The two domes are already leaking in many places, with the paintings on them long spoiled. The bookshelves are completely rotten, and the books and records missing – the best-case result for them would be to appear in the ancient book market of the Southern Capital Bazaar and to be picked and brought as the foundation of the library collection by lecturers from the Southern Capital Zhongzhi Academy* (種智院) who understand the values of them. As for the worst-case scenario, I’d rather prefer not to speak of it.

*(Note: the Southern Capital Zhongzhi Academy has been, in a long time, the only modern university in Mahakhitan, although during the 16th-17th Centuries many places of the empire had quite a lot ancient theological academies and some Confucian colleges, whose later modernisation shall be saved for future introductions possibly. 種智院/“Planting Wisdom Court”, the Buddhism-influenced name IOTL is actually used by a Japanese university 種智院大学/Shuchiin University)

------------------------------------------------------------------

Going westward along the northern road of the palaces, the bedroom palace of the empress and her husband back then, Ziwen Hall (紫文殿, lit. “Purple Cultured Hall”) is to the south of the long corridor.

We seem to have mentioned that during the fifty years the palaces were not in use, countless craftsmen used to visit the Southern Capital palaces with various methods. Ziwen Hall, on top of anything else, was the main reason why these people were willing to spend a fortune to bribe the guards and sneak into the palaces risking their lives.

After the civil war, the Southern Capital was the first to recover thanks to the trade through the Indian Ocean, and was where some newly rich of the empire gathered to live during the twenty odd years thereafter. The building fashions popular among them were not as rigid and obsessed with rites like in the case of the old aristocrats, so the rebellious – by the standard back then – and incredibly luxurious Southern Capital palaces became their primary reference.

Being suspected of breaking the hierarchy (specifically called 逾製/Yu2 Zhi4 in Chinese) was hardly avoidable, but the grey area between allowed much room for maneuvering. The craftsmen in Southern Capital had ten thousand ways to cleverly bypass the red line. On the other hand, the debilitated imperial family now depended on the support of these upstarts, and released signals of “temporary acquiescence” in many aspects – the silent approval of newly emerged merchant class dressing in exclusively aristocratic patterns and colours during the years of Chongguang should be quite revealing.

Therefore, the new generation of the Liao Southern Capital civilian residential buildings, compared to their grey, humble predecessors, showed a much more obvious “official look”. Known as the “empress style”, it became the symbol of the 16th-17th Centuries Mahakhitan architecture, with its origin traced back to the Ziwen Hall here.

In contrast to the more rigid halls including the Yunhe and the Changqing, the space allocation and dimension of Ziwen Hall are the most user-friendly, and most casually designed as the private space of the imperial family. As a result it has been the most favoured reference among civilians.

Northern terrace of Ziwen Hall.

This hall mingles all Her Majesty’s favourite elements. The “Water Fringe Lake (荇海子, where /Xing4 refers to Nymphoides peltata, or fringed water lily, or water fringe while 海子/small sea in ancient Chinese often meant lake or pool)” to the north of Ziwen Hall is almost a Persian-style garden. The southern side of the hall is on the other hand the arcade overlooking the entire Indus Delta that bears quite some resemblance to Boukoleon Palace of Constantinople. The Feathers Lake (羽淀, where 羽 means Feather, and 淀 is the traditional local way of calling a water body – lakes or swamps – in northern China) to the east of the hall is on the other hand an open palace garden with an artificial stream. However, at the end of the stream lies a central Sindhu-style stair well, through which water from the surface of the palace garden gather and flow back to the giant reservoir underneath the palaces.

That’s right, following the advice of the hired Fulin craftsmen, in order to level the base and make the palaces visually larger, most of the palace complex is built upon arches, thus forming the gigantic water reservoir under the buildings that helps to cool down the palaces during harsh summers and provides water for landscape and consumption uses.

In the meantime, the consequent underground corridors also have become the transit route for the hundreds of palace servants as well as part of the guardian system, successfully rendering this rather small palace complex not as seemingly crowded in regular days.

Inside the walls of Ziwen Hall there is supposedly a bronze pipe system for the cooling of the walls and roof, but we regrettably cannot personally experience its effect.

It has been said that back then, the empress and the Shanyang King would cuddle together on one of the countless terraces of Ziwen Hall, spending one after another afternoons in the undisturbed shades of trees. The country was rich as it never had been, and the two sons Dun and Jing (both became emperors years later, as Minzong/愍宗 and Pingzong/平宗) and two little daughters growing up day by day. It was as if the happiness of this tiny family would last forever.

------------------------------------------------------------------

King Xuan of Shanyang passed away in March, the 27th Year (of Duanning; 1497), at the age of forty-five.

It was said at the funeral, she put her favourite neckwear on the chest of the Shanyang King. “See the necklace as I am here.” She said.

The empress never wore a single jewelry since then.

------------------------------------------------------------------

Later historians always claimed that since the death of the Shanyang King, some the empress’ policies in her late years appeared to be too radical, and threatened the vested interests of too many classes, thus probably served as the initial trigger of the subsequent turmoil the empire suffered. In her late years, the campaign against Tianfang (1504-1507) was also extremely costly both in expenditures and human lives. Although four years of bitter war was concluded with the final victory, the navy that the state of Liao took pride in almost lost all of its main forces, along with the vessels and talents previously shined in the great voyages. Her appointment of Ü-Tsang monks as officials was also met with resentment from the Liao bureaucrats and monks, whereas the “Tianfang special tax” during her last few years led to grudges of the Southern Capital merchants.

It was even rumoured in the capital, that the empress and her son-in-law, the prince of Ü-Tsang kept an unspeakable relationship. But the empress herself did not seem to have heard anything. Indeed, she was making less and less appearances in front of her court officials, while the palace servants said she was always sitting idly in the imperial Buddhist hall in the Southern Capital palaces – the Yaoguang Hall. No one knew what she had been thinking, and the people’s image of her was undergoing changes.

One day in the 37th Year of Duanning (1507), the empress and the crown prince (the future Minzong Emperor) had a brief argument regarding a certain policy concerning Kangzhou. In Qijuzhu (起居注, lit. “rise and live record”, which was the name of the record of the daily behavior, schedule and words of ancient Chinese emperors) the last segment of their conversation was recorded.

In the record, the empress admitted that without the help of the Shanyang King, she found it hard to grasp a lot of situations. When faced with her son that had issues with her order, she said her time was limited. Therefore she was determined to push reform measures that would provoke the aristocracy to the very end and finish the most costly battles with her own hands, so that when her son inherit the throne, he would be able to show his most merciful side and even abolish some of empress’ “bad policies” so as to win more admiration from his subjects.

The crown prince burst into tears and kneeled for so long without getting up.

------------------------------------------------------------------

39th Year of Duanning (1509), the empress passed away in Ziwen Hall, Southern Capital. The palaces were since left uninhabited.

1st Year of Jiazhi (1510), many in the court opposed to discuss the temple name for the empress by the excuse of maintaining appropriate rites. Spirit tablets in Ancestral Temple of Central Capital were seen in tears.

14th Year of Jiazhi (1523), the Guiwei Rebellion broke out.

21st Year of Jiazhi (1530), Hanshan and Kangzhou forces besieged the Central Capital. Many lords joined the ranks of the rebel forces. The emperor, the queen and the crown prince were killed by rebels in camp. His Majesty’s younger brother Yelü Jing succeeded to the throne in Tianzhu Circuit, changing the year name to Chongguang.

------------------------------------------------------------------

“… Winter nights, summer days.

“……冬之夜,夏之日。

… after a hundred years (a metaphorical lifetime),

……百岁之后,

… I join you in our grave.”

……归于其室。”

“… Winter nights, summer days.

“……冬之夜,夏之日。

… after a hundred years (a metaphorical lifetime),

……百岁之后,

… I join you in our grave.”

……归于其室。”

*The captions of the three pics above form the last line of the poem Creeping Vine (Ge Sheng) in Odes of Tang, Classics of Poetry. Kara's original captions in Simplified Chinese are left unchanged.

Hm, speaking of one’s destiny, of course it depends on striving by one’s self, but the course of history should be taken into account too.

Also, even the most powerful individual in the world would be as fragile as a child when left all alone.

Last edited:

Chapter 23 Mahakhitan Armies during the Expedition in Southern China, 1630

Chapter 23 Mahakhitan Armies during the Expedition in Southern China, 1630

023 – 華南遠征中的摩訶契丹軍隊,1630

Part two of the fabricated Ospery publication, Early Modern Khitan Armies, 1500-1800!

Selected content from inner pages:

The Campaign to Aid Ming was a medium-scale military campaign the Liao carried out in East Asia during 1628-1631. The Ming Empire suffered severe economic crises and military defeats in the early 17th Century. Peasant rebel forces were expanding into northern China and multiple provinces in the south, while the Jurchen Later Jin state to the north was also eager to move. In 1611 and 1624, the Later Jin twice breached the Great Wall and pillaged northern China. By 1627, an inner peasant rebel force captured Peking (now, Beijing, the “Northern Capital”), established the “State of Great Shun” (大順國, lit. “Great Obedience State”). As the Ming emperor fled to Nanking (now Nanjing, the “Southern Capital”), Later Jin forces exploited the opportunity and went all out in a southward campaign, successfully expelling the remaining peasant forces to western China (Note 1).

[Note 1: Due to economic and climate disturbances in the timeline, the disaster of Ming Dynasty came ten-odd-years earlier compared to OTL. The unfolding was still relatively similar, just that the emperor and leader(s) of the peasant rebellion(s) are not whom we are familiar with anymore. Also noteworthy is that this time the monarchy of Later Jin was from the Yehe Nara clan of Haixi (“Sea-West”) Jurchens.]

The Ming emperor, holding his stand in Nanking and keeping up the fight, sent requests for help to the various foreign powers including those in Europe. The French and Andalusians promised to provide dozens of 32-pound cannons along with the crews through the Jesuits, while the English, Dutch and Castilians ambiguously claimed to “remain neutral” between the Ming, Shun and Jin. The one to truly provide aid in bulk was the state of Mahakhitan.

The Jurchen invasion of northern China reminded the Liao aristocrats of the dark history experienced by their own ancestors back in the 12th Century, but this alone would not make up the Liao emperor’s mind to fund such a long, costly expedition. In contrast, the prospect of extending their business reach to the Indo-China Peninsula and southern China greatly cheered the merchants of Liao, as they believed the expedition would be a fantastic chance to restore the relationship with Ming after the Dali Incident in 1610, and to further gain trade privileges. The debate on the expedition within the Liao Empire only went on briefly, after which the imperial Ministry-Office-Council (this is how the Liao collectively called their three central military agencies which had partially overlapping duties and powers: Ministry of War, Office of Generalissimo, and Privy Council) promptly dived into the preparation works on the ground.

The troops to take part in the expedition included 10,000 infantries equipped with muskets and 3,000 light artillery crew, making up a total of twenty battalions. Due to the terrain in southern China and supply difficulties, Liao did not send cavalries.

These troops mainly came from the Liao imperial guards, the Xiongwu Army and the Shanyang Army, reorganised as two parts and called the Jingning Left Army and Jingning Right Army (靖寧/Jingning literally means “Pacifying/Pacification”), respectively. In order to ease communications, lead commanders of the two armies were both Han descendants. In addition, the expeditionary forces also included 110 transport ships and light warships, as well as nearly 8,000 sailors and logistical personnel. According to the agreement between Liao and Ming, the Liao forces would mainly encircle and suppress the “Great Xi” (大西, lit. "Great West"; Note 2) roving rebels in provinces including Guangdong, Jiangxi, Hunan, Hubei and so on, so as to help the Ming forces moving northward to continue the fight in the Jianghuai region (江淮, the region between the downstream of the Long/Yangtze River – Jiang, and Huai River - Huai).

[Note 2: We will for the time being settle for the lack of creativity of these uprising leaders as the reason why they stuck to such names, but they did have different spheres of activity compared to the cases IOTL.]

The convoy sailed out from the Bay of Bengal in May, 1628, and arrived in Guangzhou (“Canton”) in August the same year. After landing, the two armies rested until early winter, and then split towards the north. The Left Army moved into Human via Shaozhou Prefecture, and the Right Army entered Ganzhou to continue moving northward along the Gan River.

Despite their limited numbers, the Liao armies still faced serious logistical problems during the northward expedition, with cases of “gathering grass and grain” (打草穀, the term used by OTL Liao Dynasty troops for robbing and pillaging) once taking place in early 1629, leaving some bad reputation of the Liao troops in Hunan and Jiangxi. As the Liao Dhyana/Zen monks contacted and asked for help from related factions such as the Caodong School (曹洞) and Hong Men (洪門, mostly known as the Tiandihui in English), and also thanks to the gradual restoration of local order in the southern regions of Ming, by the summer harvest season of 1629, the supply for the armies was increasingly sufficient. The Liao navy established a small stronghold in the south of the island of Taiwan, named it “Dayuan Guard” (大員衛/Dayuan Wei, from “Teoyowan” in one of the aboriginal languages) according to the language of the natives there, and used it as the anchorage for logistical shipping. In the future, it became a major transit for Mahakhitan’s trade with Ming.

The Liao military personnel in the picture was wearing cotton armour with Mahakhitan features. The South Asian Subcontinent abounded with cotton and helped greatly reducing the cost of this kind of armour. The armours for generals and officers were reinforced with metal armour pieces of various sizes, and had sophisticated embroidery as decorations. In contrast, the armours for soldiers were extremely light and practical. Similar to the case of Europe of the same period, the Mahakhitan infantries only stressed the protection of the upper body. The cutton armours worn by Ming generals and officers on the other hand had steel-made arm-armours and smaller “chest plates” (護心鏡, lit. “Protecting Heart Mirrors”). The cotton armours of the two countries both originated from the tradition of the Mongol Empire’s light armours, but had been developed along different paths. By this point, expensive and sophisticated European wheel-lock firearms had not made it to the Asian Continent, and muskets were still being slowly popularised in the eastern empires. As the expeditionary Liao forces were drawn from relatively elite standing armies, their rate of being equipped with muskets was significantly higher than the average level among Ming forces.

The Liao forces eradicated the Great Xi forces along the Xiang River and Gan River basins on their way northward, and took cities such as Changsha, Yuezhou, Jiujiang with assistance from Ming forces. The Left and Right Armies joined force in summer 1630, and besieged the major city under the control of the Great Xi peasant army, Wuchang Prefecture, along with 100,000 Ming troops. After capturing Wuchang, the Liao forces further fended off a Later Jin attack on Wuchang in early 1631, and launched counter offensives that reached as far as around Xiaogan, thus making great contributions for the Ming effort to consolidate the Yangtze River line of defense as well as the later counter attack towards the Han River basin. The formidable firepower projection performance of the Liao firearm battalion(s) also stimulated the acceleration of the mass-equipment of “fowling pieces” (鳥槍, lit. “bird guns”) among Ming troops.

November 1631, after completing the battles of wiping out the roving rebels in southern China, the main forces of the Liao armies, assisted by the navy, retreated back to Dayuan Guard and Guangzhou Prefecture via the Yangtze River and the open sea, and then went back to their country in batches. Among the initial 13,000 Jingning Army officers and soldiers, only half made it back to Liao. It is also worth mentioning that this army in the meantime brought back many impoverished southern Ming soldiers and civilians that had no other way out but to join the Liao forces as auxiliary personnel. The ships eventually returning to the Bay of Bengal were even considerably more packed than when they were leaving for China.

023 – 華南遠征中的摩訶契丹軍隊,1630

Part two of the fabricated Ospery publication, Early Modern Khitan Armies, 1500-1800!

Battle of Yuezhou (岳州), 1630

The flag in the back says "Help the Ming and fight the bandits".

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

The flag in the back says "Help the Ming and fight the bandits".

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Selected content from inner pages:

The Campaign to Aid Ming was a medium-scale military campaign the Liao carried out in East Asia during 1628-1631. The Ming Empire suffered severe economic crises and military defeats in the early 17th Century. Peasant rebel forces were expanding into northern China and multiple provinces in the south, while the Jurchen Later Jin state to the north was also eager to move. In 1611 and 1624, the Later Jin twice breached the Great Wall and pillaged northern China. By 1627, an inner peasant rebel force captured Peking (now, Beijing, the “Northern Capital”), established the “State of Great Shun” (大順國, lit. “Great Obedience State”). As the Ming emperor fled to Nanking (now Nanjing, the “Southern Capital”), Later Jin forces exploited the opportunity and went all out in a southward campaign, successfully expelling the remaining peasant forces to western China (Note 1).

[Note 1: Due to economic and climate disturbances in the timeline, the disaster of Ming Dynasty came ten-odd-years earlier compared to OTL. The unfolding was still relatively similar, just that the emperor and leader(s) of the peasant rebellion(s) are not whom we are familiar with anymore. Also noteworthy is that this time the monarchy of Later Jin was from the Yehe Nara clan of Haixi (“Sea-West”) Jurchens.]

The Ming emperor, holding his stand in Nanking and keeping up the fight, sent requests for help to the various foreign powers including those in Europe. The French and Andalusians promised to provide dozens of 32-pound cannons along with the crews through the Jesuits, while the English, Dutch and Castilians ambiguously claimed to “remain neutral” between the Ming, Shun and Jin. The one to truly provide aid in bulk was the state of Mahakhitan.

The Jurchen invasion of northern China reminded the Liao aristocrats of the dark history experienced by their own ancestors back in the 12th Century, but this alone would not make up the Liao emperor’s mind to fund such a long, costly expedition. In contrast, the prospect of extending their business reach to the Indo-China Peninsula and southern China greatly cheered the merchants of Liao, as they believed the expedition would be a fantastic chance to restore the relationship with Ming after the Dali Incident in 1610, and to further gain trade privileges. The debate on the expedition within the Liao Empire only went on briefly, after which the imperial Ministry-Office-Council (this is how the Liao collectively called their three central military agencies which had partially overlapping duties and powers: Ministry of War, Office of Generalissimo, and Privy Council) promptly dived into the preparation works on the ground.

The troops to take part in the expedition included 10,000 infantries equipped with muskets and 3,000 light artillery crew, making up a total of twenty battalions. Due to the terrain in southern China and supply difficulties, Liao did not send cavalries.

These troops mainly came from the Liao imperial guards, the Xiongwu Army and the Shanyang Army, reorganised as two parts and called the Jingning Left Army and Jingning Right Army (靖寧/Jingning literally means “Pacifying/Pacification”), respectively. In order to ease communications, lead commanders of the two armies were both Han descendants. In addition, the expeditionary forces also included 110 transport ships and light warships, as well as nearly 8,000 sailors and logistical personnel. According to the agreement between Liao and Ming, the Liao forces would mainly encircle and suppress the “Great Xi” (大西, lit. "Great West"; Note 2) roving rebels in provinces including Guangdong, Jiangxi, Hunan, Hubei and so on, so as to help the Ming forces moving northward to continue the fight in the Jianghuai region (江淮, the region between the downstream of the Long/Yangtze River – Jiang, and Huai River - Huai).

[Note 2: We will for the time being settle for the lack of creativity of these uprising leaders as the reason why they stuck to such names, but they did have different spheres of activity compared to the cases IOTL.]

The convoy sailed out from the Bay of Bengal in May, 1628, and arrived in Guangzhou (“Canton”) in August the same year. After landing, the two armies rested until early winter, and then split towards the north. The Left Army moved into Human via Shaozhou Prefecture, and the Right Army entered Ganzhou to continue moving northward along the Gan River.

Despite their limited numbers, the Liao armies still faced serious logistical problems during the northward expedition, with cases of “gathering grass and grain” (打草穀, the term used by OTL Liao Dynasty troops for robbing and pillaging) once taking place in early 1629, leaving some bad reputation of the Liao troops in Hunan and Jiangxi. As the Liao Dhyana/Zen monks contacted and asked for help from related factions such as the Caodong School (曹洞) and Hong Men (洪門, mostly known as the Tiandihui in English), and also thanks to the gradual restoration of local order in the southern regions of Ming, by the summer harvest season of 1629, the supply for the armies was increasingly sufficient. The Liao navy established a small stronghold in the south of the island of Taiwan, named it “Dayuan Guard” (大員衛/Dayuan Wei, from “Teoyowan” in one of the aboriginal languages) according to the language of the natives there, and used it as the anchorage for logistical shipping. In the future, it became a major transit for Mahakhitan’s trade with Ming.

The Liao military personnel in the picture was wearing cotton armour with Mahakhitan features. The South Asian Subcontinent abounded with cotton and helped greatly reducing the cost of this kind of armour. The armours for generals and officers were reinforced with metal armour pieces of various sizes, and had sophisticated embroidery as decorations. In contrast, the armours for soldiers were extremely light and practical. Similar to the case of Europe of the same period, the Mahakhitan infantries only stressed the protection of the upper body. The cutton armours worn by Ming generals and officers on the other hand had steel-made arm-armours and smaller “chest plates” (護心鏡, lit. “Protecting Heart Mirrors”). The cotton armours of the two countries both originated from the tradition of the Mongol Empire’s light armours, but had been developed along different paths. By this point, expensive and sophisticated European wheel-lock firearms had not made it to the Asian Continent, and muskets were still being slowly popularised in the eastern empires. As the expeditionary Liao forces were drawn from relatively elite standing armies, their rate of being equipped with muskets was significantly higher than the average level among Ming forces.

The Liao forces eradicated the Great Xi forces along the Xiang River and Gan River basins on their way northward, and took cities such as Changsha, Yuezhou, Jiujiang with assistance from Ming forces. The Left and Right Armies joined force in summer 1630, and besieged the major city under the control of the Great Xi peasant army, Wuchang Prefecture, along with 100,000 Ming troops. After capturing Wuchang, the Liao forces further fended off a Later Jin attack on Wuchang in early 1631, and launched counter offensives that reached as far as around Xiaogan, thus making great contributions for the Ming effort to consolidate the Yangtze River line of defense as well as the later counter attack towards the Han River basin. The formidable firepower projection performance of the Liao firearm battalion(s) also stimulated the acceleration of the mass-equipment of “fowling pieces” (鳥槍, lit. “bird guns”) among Ming troops.

November 1631, after completing the battles of wiping out the roving rebels in southern China, the main forces of the Liao armies, assisted by the navy, retreated back to Dayuan Guard and Guangzhou Prefecture via the Yangtze River and the open sea, and then went back to their country in batches. Among the initial 13,000 Jingning Army officers and soldiers, only half made it back to Liao. It is also worth mentioning that this army in the meantime brought back many impoverished southern Ming soldiers and civilians that had no other way out but to join the Liao forces as auxiliary personnel. The ships eventually returning to the Bay of Bengal were even considerably more packed than when they were leaving for China.

Last edited:

Chapter 24 The Boiling Ocean: Introduction to the 17th Century Indian Ocean Trade, with Many Maps

Chapter 24 The Boiling Ocean: Introduction to the 17th Century Indian Ocean Trade, with Many Maps

024 – 沸騰的海洋:17世紀的印度洋貿易概述,附大量地圖

The Europeans discovered the southern Indian Ocean sea lane in mid 16th Century. Instead of the route taken by the voyagers before them, now European merchant ships could skip stopping by East Africa and the Indian coast and directly take the west wind once they passed Cape of Good Hope until arriving in Java and the Spice Islands through the open waters near Australia.

The main (red) and secondary (cyan) Indian Ocean trade routes – just like in the history of OTL.

By mid 17th Century, such an outlook was formed: the “main” sea route of the southern ocean almost completely belonged to the galleons of Europeans, whereas the coastal trade was conducted by the merchant ships of the countries that bordered the Indian Ocean.

Trade in the Mediterranean used to experience ups and downs several times during the 16th Century, but the course of history was proved difficult to resist. During 1580-1600, the Mediterranean trade route finally withered, with Rome, Tianfang (Arabic Kingdom under the House of Hashemites) and the Caliphate (formerly Kingdom of Iraq, Liao's ally for three centuries) being the ones that were hit the hardest.

The inland routes, due to their completely different destinations, managed to remain free from being directly affected. The Liao Central Capital city, after the sufferings brought by the civil war in early 16th Century, was in decline, but the Afghan trade lane was still enjoying prosperity, allowing this city to keep its status as the regional business hub. The entire Persian-Afghan trade lane did not experience decline until 1750.

However, what will entertain us today would still be stories of the boiling Indian Ocean in the 17th Century.

The spice smuggling wars all over the Indian Ocean had begun in as early as the 1580s. One side of the “battles” were the state of Liao that, with her ten Bureaus for Foreign Shipping, intended to consolidate her monopoly over the trade in the east, while the other side were the newcomers in the Indian Ocean that wanted to directly engage in the trade of spices such as England and the Netherlands.

Liao had realised the Europeans’ southern sea lane was causing trade losses, and began to set her own plan in Jinzhou (the generalised name in Indian languages for the Malay Peninsula, Kalimantan and Sumatra). The newly built Liao navy started to be stationed at the pre-existing Khitan plantations and trade points in southern Kalimantan from 1620. Local agencies of the Bureau for Foreign Shipping were established by the Liao government which, while attempting to build the region into a transit centre, also tried to directly tax Europeans who conducted trade along the nearby major routes. The intention was to block one end of the Europeans’ main trade routes and force them to stomach the taxation by the Liao Bureaus of Foreign Shipping in Jinzhou and Johore if they wished to do business in the Spice Islands, China and Japan.

But on the high seas of the 17th Century, any attempt to reach trade monopoly could not have been too successful given the technological level back then. Ming sea trader groups and Liao’s very own sea traders themselves were massively smuggling to any buyer that had gold in their pockets. The Europeans also had their own alternatives other than Mahakhitan – the Kingdom of Pasai controlling the Strait of Malacca and the Kingdom of Chola located in the south of the South Asian Subcontinent. They became the most difficult competitors once they escaped from Liao’s sphere of influence.

A few other things that need to be mentioned since the beginning of the 17th Century.

Cotton cloth from India became the desirable export in trade with Europe. Every year over one thousand tons of silver flocked to Liao and Chola, rendering the silver crisis of Ming much more severe in this timeline and indirectly causing an earlier collapse of it.

Climate during the little ice age led to multiple droughts and famines from Wuchuan Circuit to Shanyang Circuit in early 17th Century. The people hit by these disasters emigrated in large scale to Liao’s Jinzhou. Some ended up in the more distant southern continent – Videha (today’s Australian west coast).

The development of Videha was mostly steered by private trading firms from Shanyang Circuit. In 1643, some Khitan herdsmen found gold mines one thousand li inland, and the news further drew more immigrants. By 1649 when the General-Governor’s Office of Videha was established, the local Liao population was approximately twenty thousand households.

Situation around the Liao in mid 17th Century (uncompressed map: https://mega.nz/#!l1omwSrQ!xGBXqqvGedt3n0_kYI2F3wkDv_ndXlajfBa1_hQgED0).

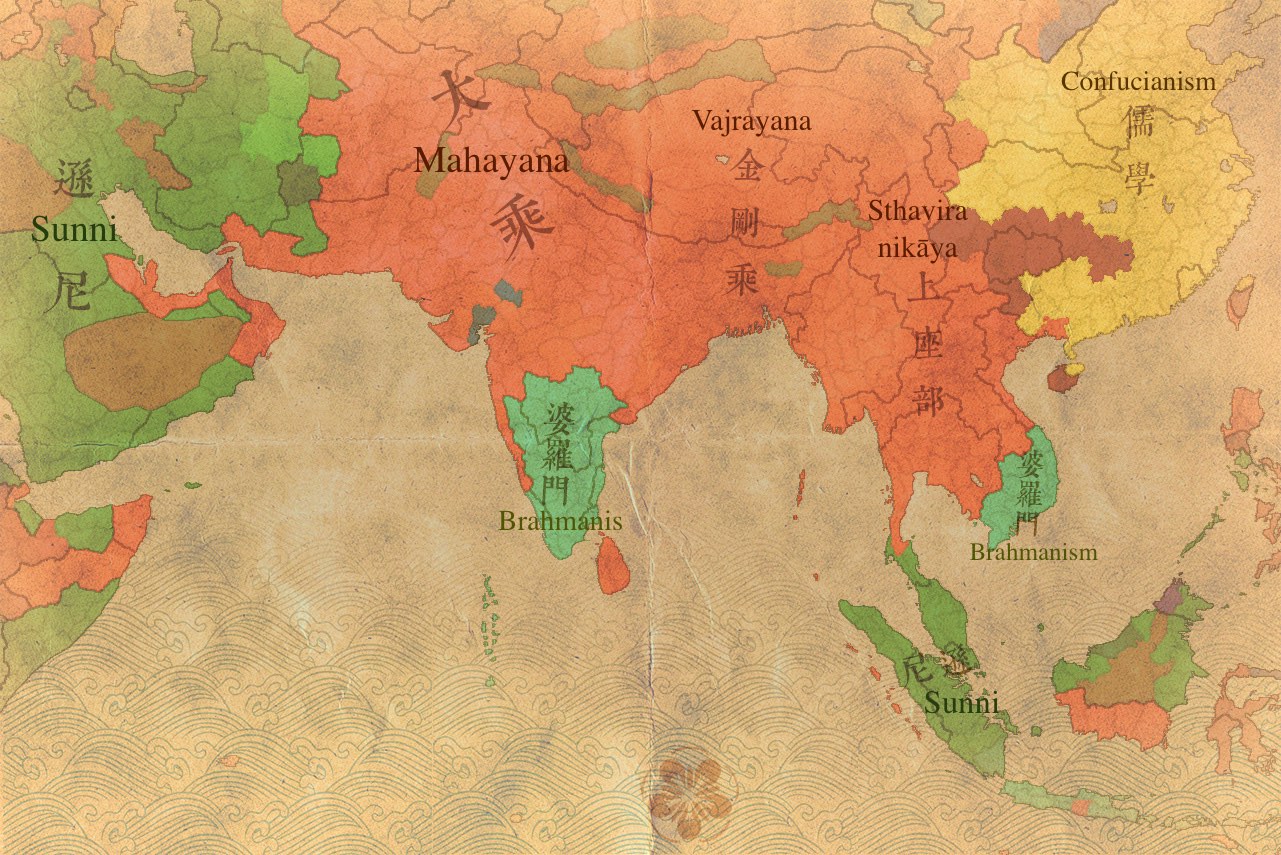

Distribution of religions in mid 17th Century (uncompressed map: https://mega.nz/#!Y0oSCSbb!JFuVRAWqwyTUf1NSNK_BIzy6V8Wt3Hl8woCtTgjvero).

Seeing the Liao setup in Jinzhou and Videha, Chola and Pasai began to feel grave danger. Around 1640, as the response to Liao’s build-up in Jinzhou, Chola leased some ports along the Coromandel and Malabar coasts to countries like England, France, Andalusia and the Netherlands, allowed these Europeans to build trade stations and forts along the coast of southern India, and bought firearms in bulk in hope of countering Liao with military support from European countries.

The subsequent counter-strike Liao launched against the Chola-Pasai alliance in turn shocked the entire Indian Ocean region as well as Europe - in 1653, an imperial edict was sent to the court of Pasai, in which the Liao emperor listed from Pasai’s betrayal of the alliance one hundred years ago to the current misdeed of the Sultan of Pasai as he connived with the pirates that were hiding along the coast of Sumatra, signaling an ominous unfolding of events between the lines.

In the war that followed, the Liao navy imposed a blockade on Sumatra and Malacca for two years, the Pasai land forces as a result were trapped in the Malay Peninsula and were then defeated by the army of Liao’s ally, Dacheng. Trade through the Strait of Malacca was cut off, almost bankrupting the English and East Roman East India Companies.

Pasai and Chola begged for surrender in May, 1657 and Liao regained control of the coasts of the strait. Twenty years of Liao expansion seemed to have completely choked the trade route of the Europeans, at least on the map.

Apart from feeling the shock, European countries still desperately tried to maintain their relationships with Liao - who would go against profit after all? Most European countries shown in the following maps had trade stations in Liao’s Southern Capital and Suluo (today’s Surat). Among them, France and Andalusia had the closest trade partnership with Liao, and enjoyed the good impression of being “submissive” in the eyes of the Liao emperor.

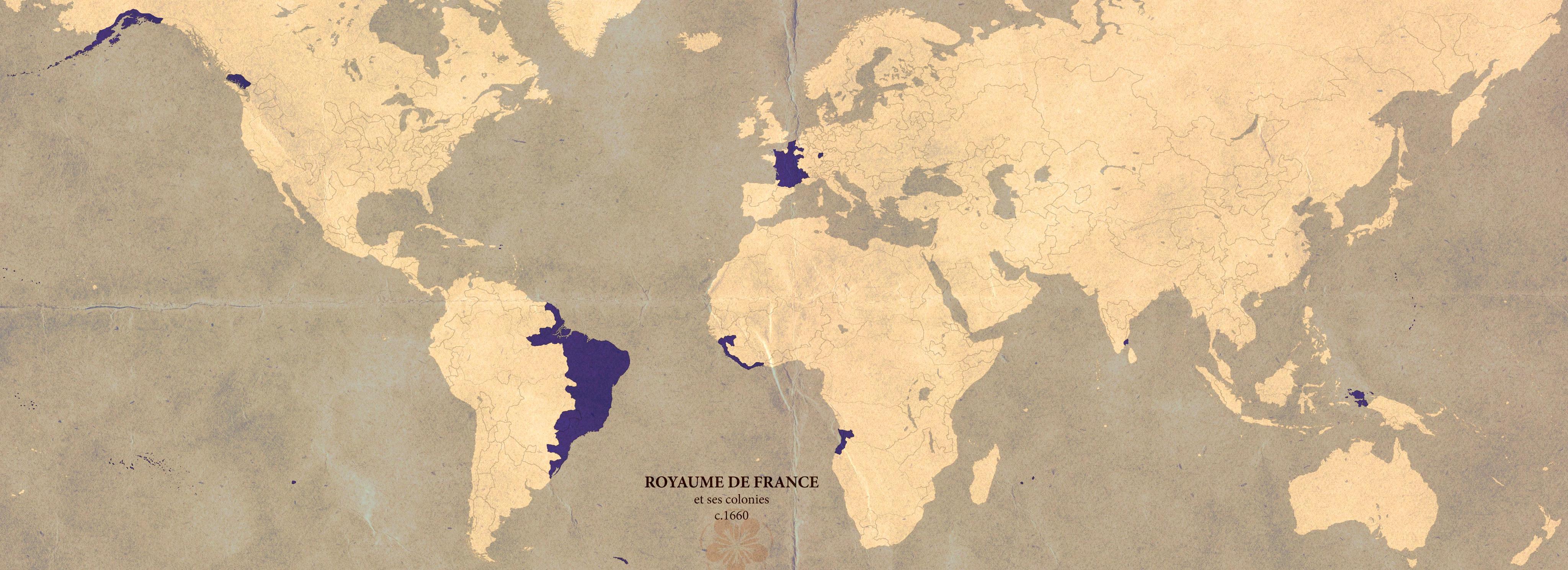

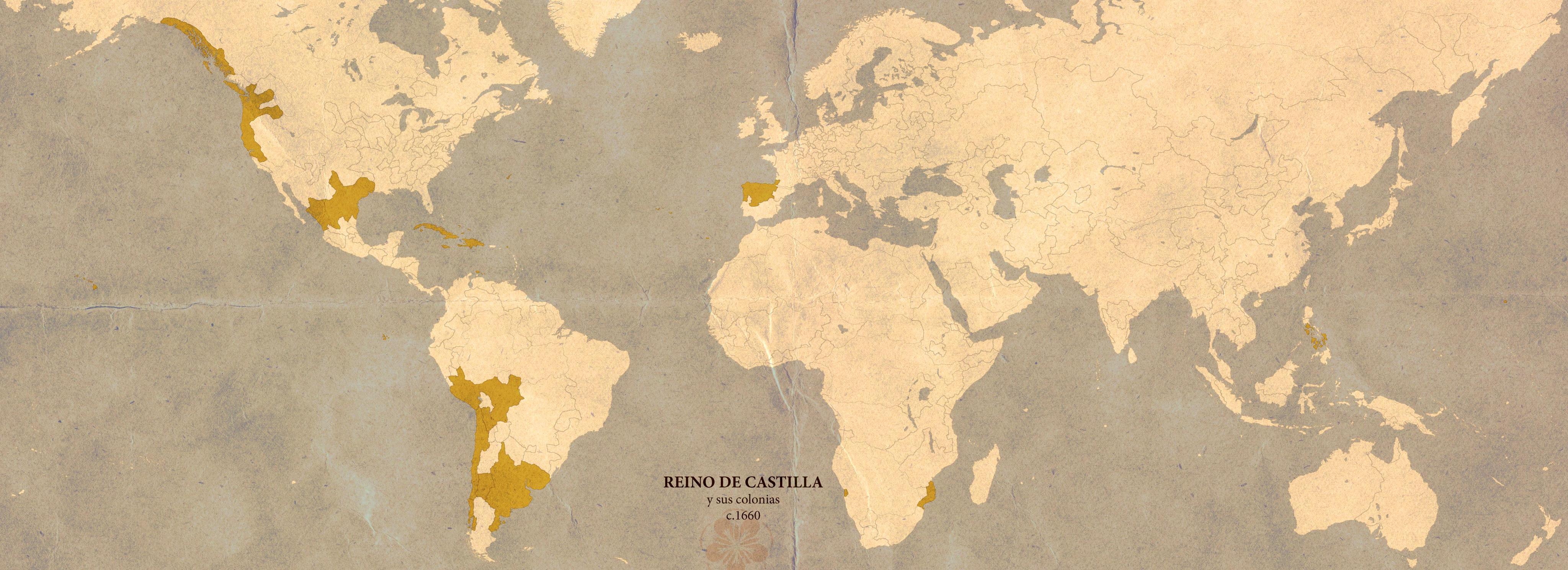

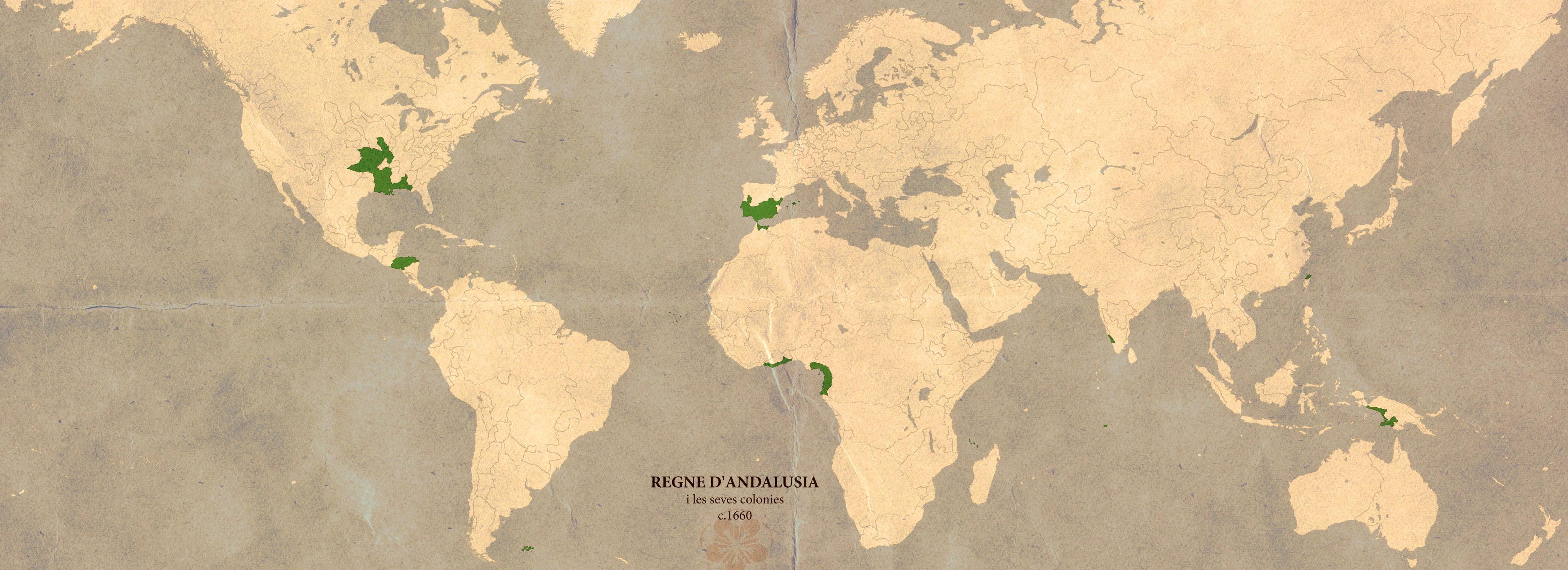

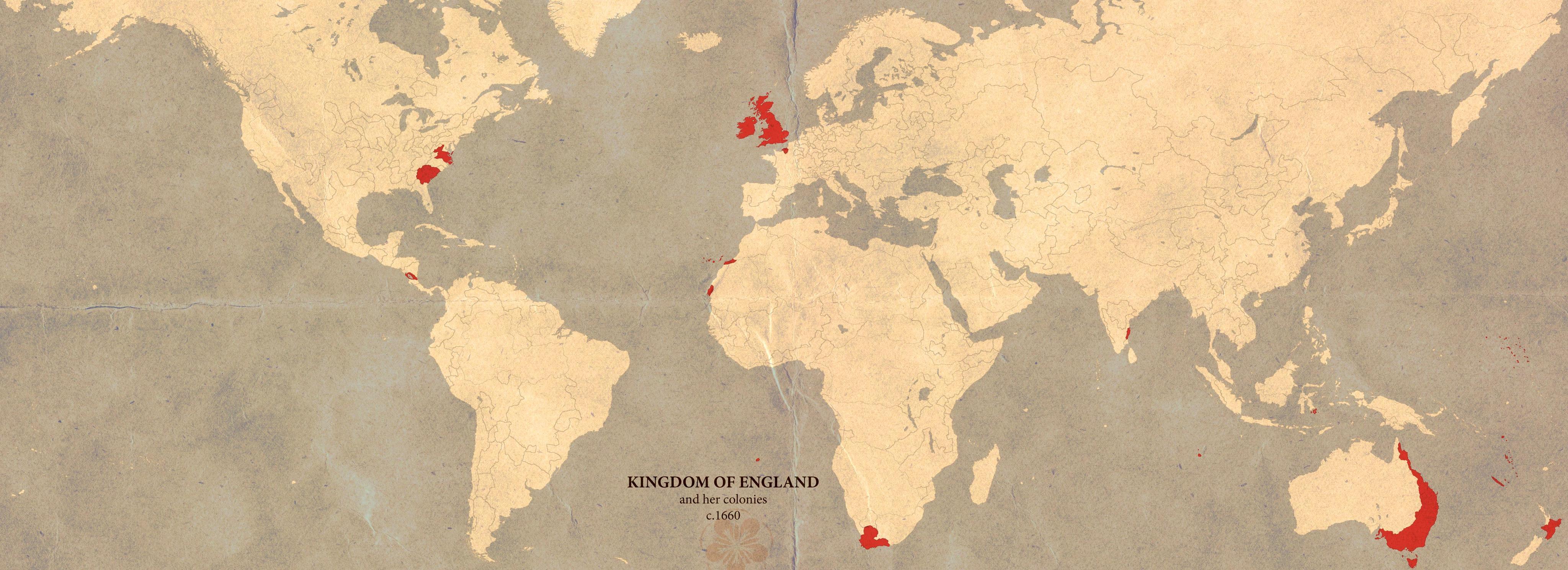

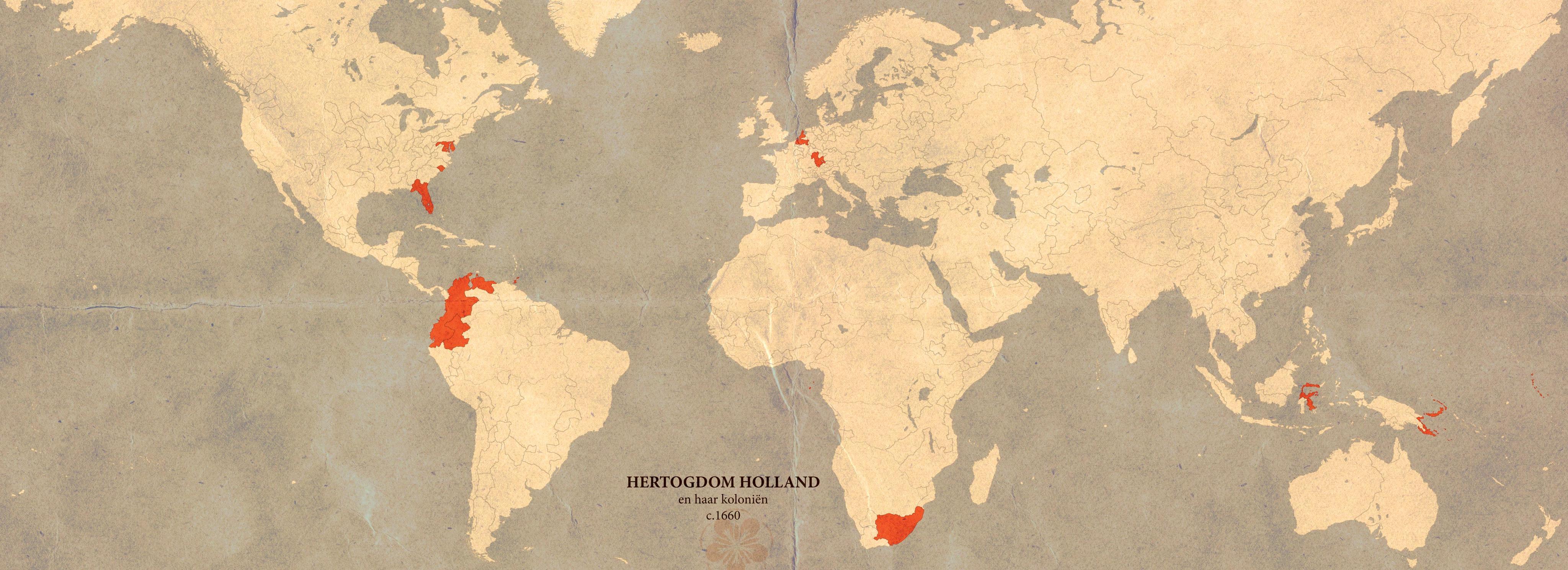

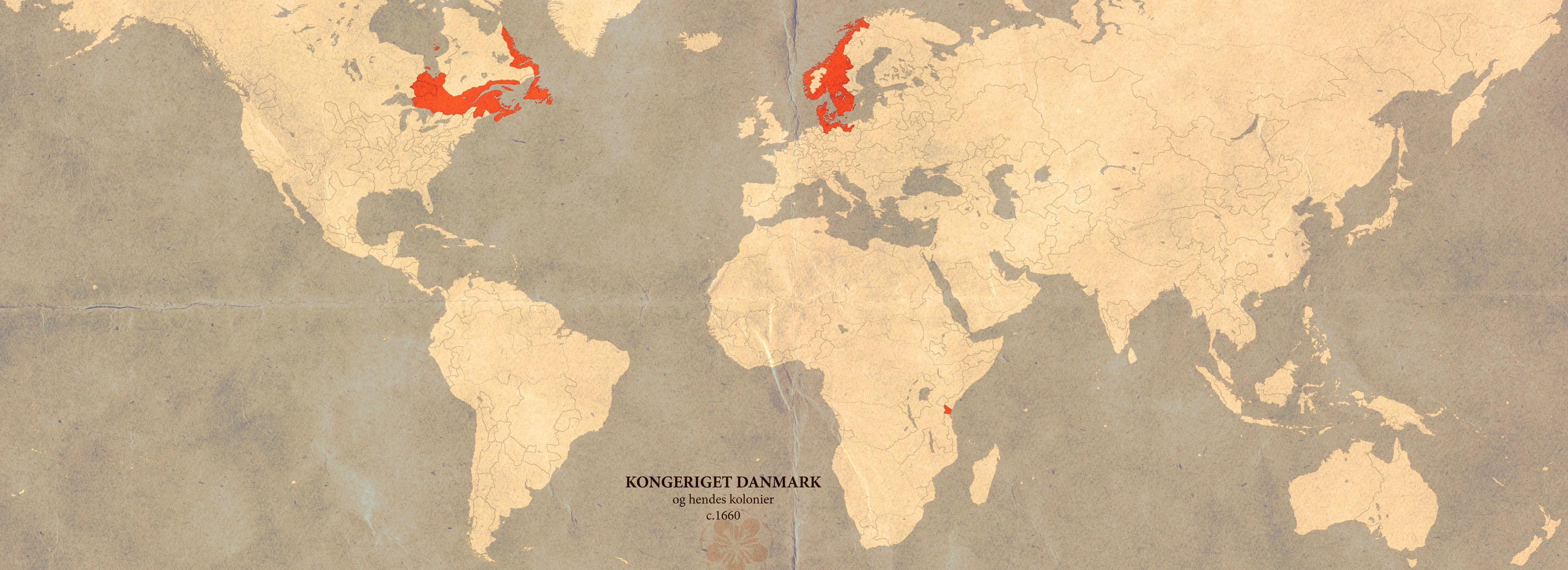

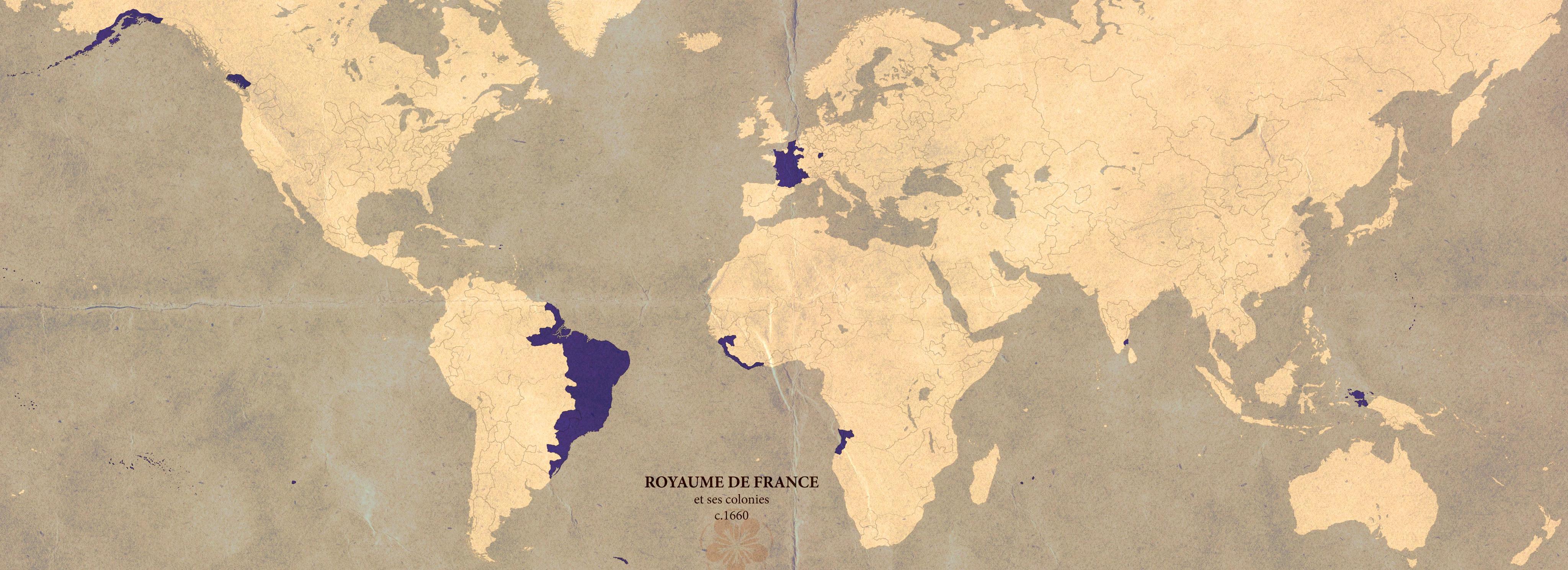

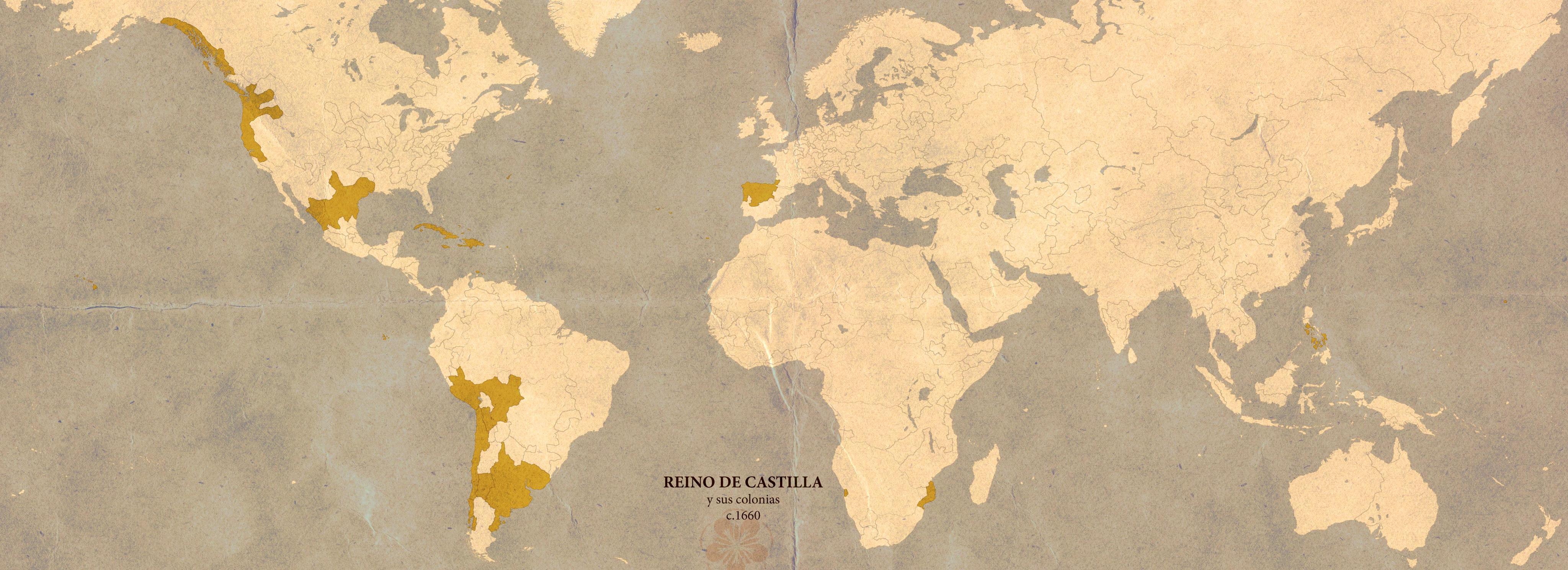

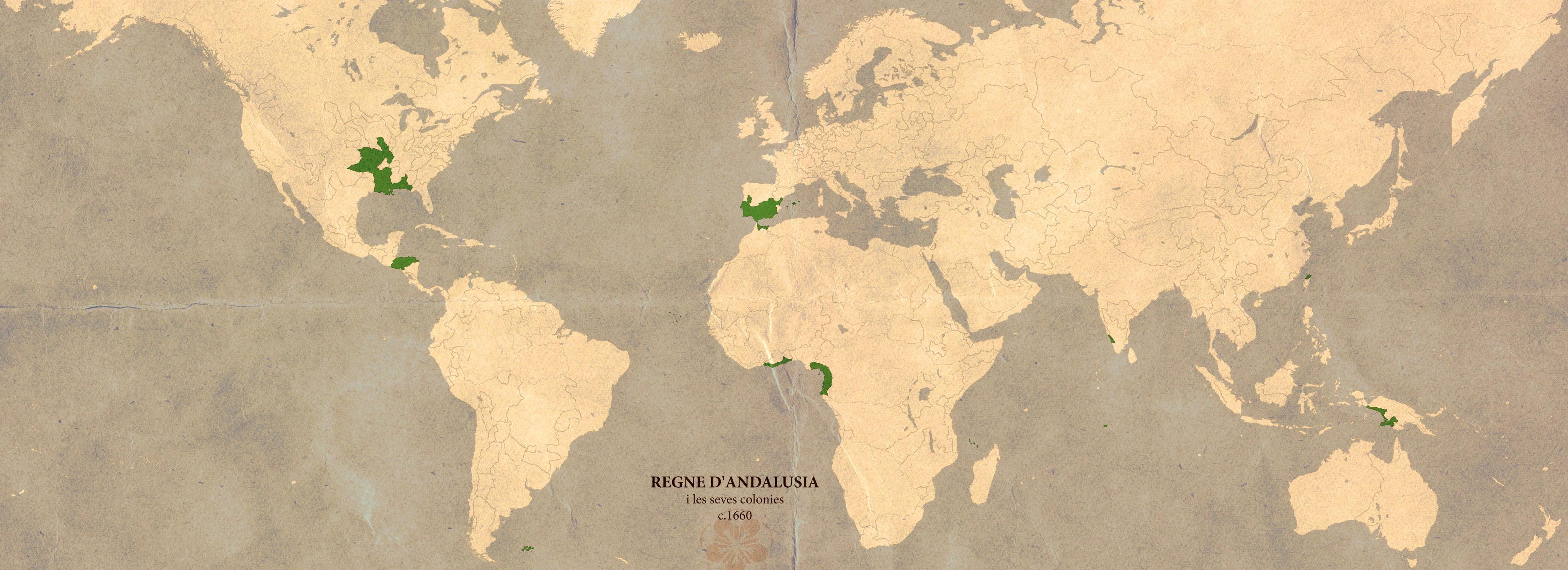

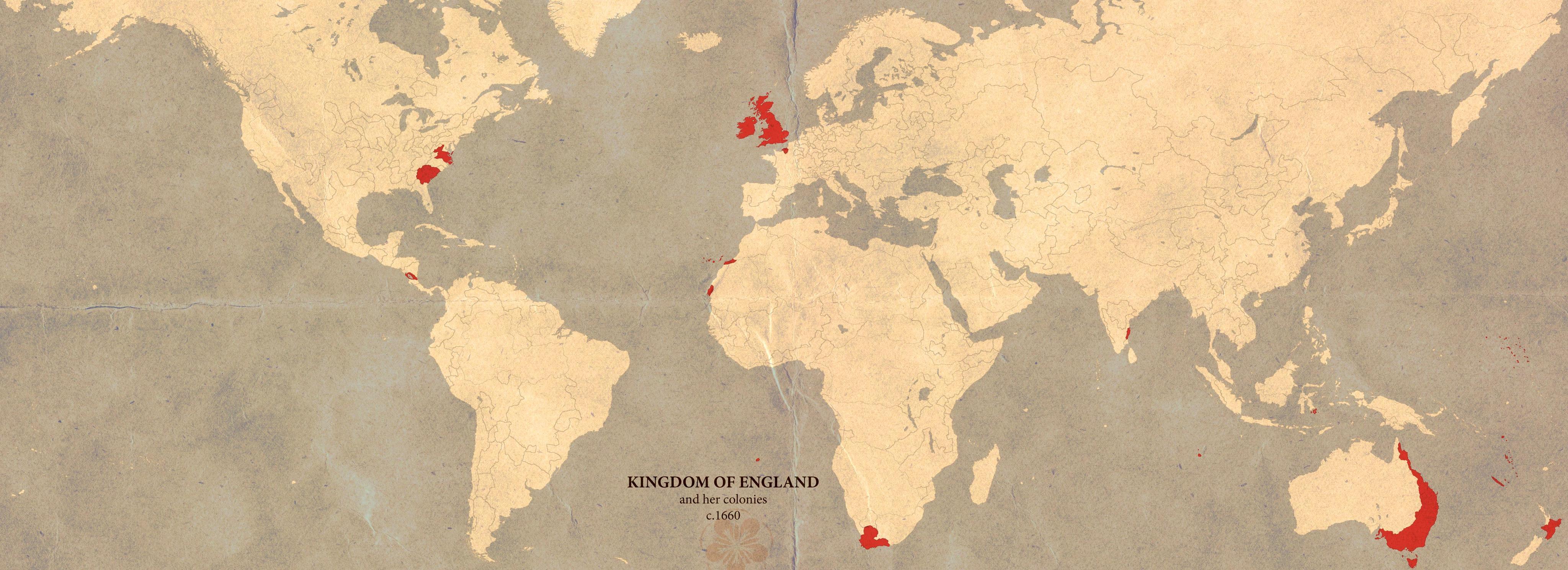

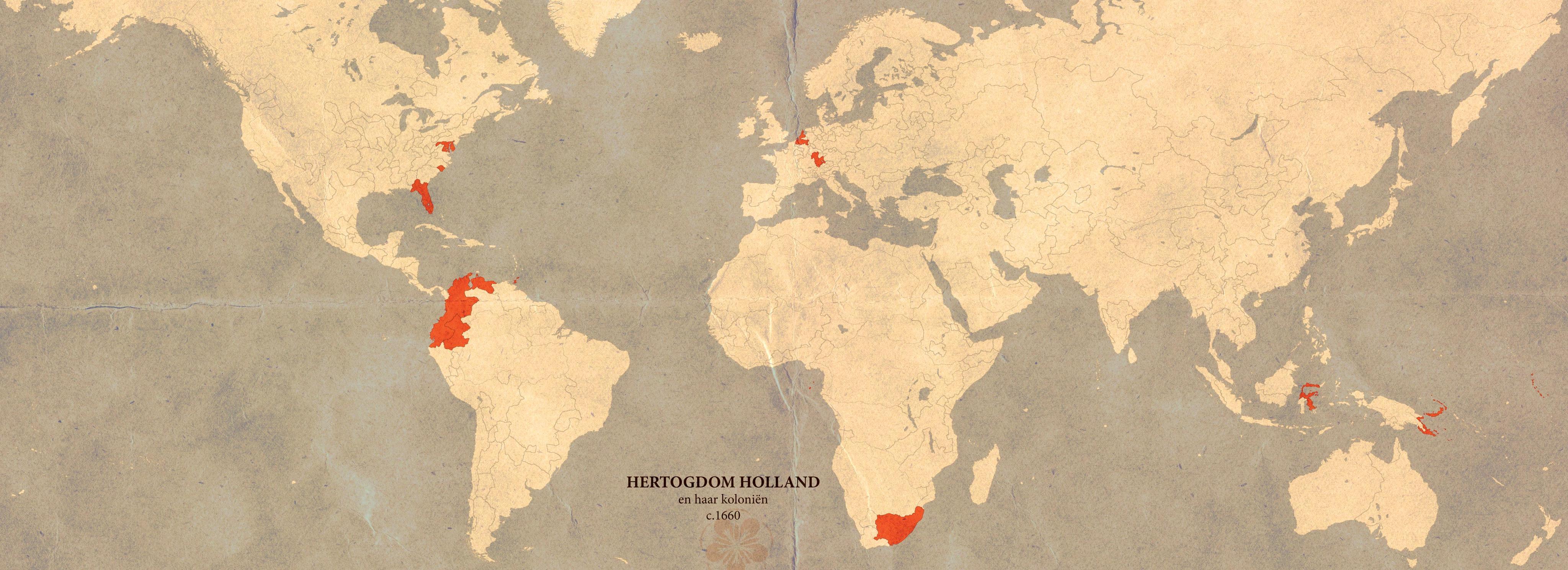

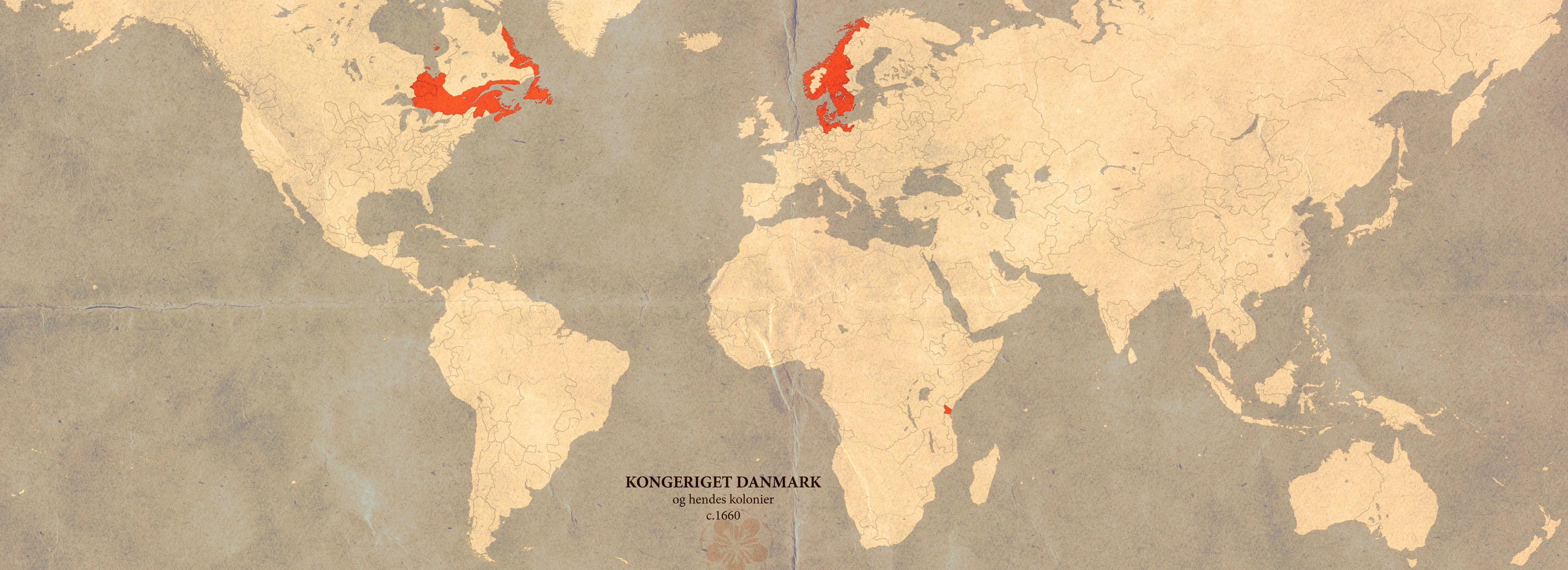

Below are the maps of the world’s global empires in 1660:

This kingdom of red tiles and white walls in sunlight has a very exciting face. Her emblem was a crowned lion between the Pillars of Hercules.

Oh, and she has another trade post, San Salvador of the Andalusian East India Company (today’s Keelung).

Also noteworthy: the Scottish aristocrats rebuilt the Kingdom of Scotland (could also be called Scotia Nuadh/New Scotia) in the New World, with the capital being Dùn Èideann Ùr/New Edinburgh (today’s Boston). Major cities include Lodainn Ùr/New Lothian (today’s southern end of the island of Manhattan) and so on.

The empire’s West India Company established two colonies, Νέα Νάξος/New Naxos (today’s Winward Islands and Leeward Islands) and Ἀμαζών/Amazones (today’s Venezuela and Guyana).

The empire’s East India Company on the other hand used Νέα Ικόνιον/New Ikónion (today’s Port Nolloth of South Africa) as a springboard for further exploration, and with the divine help of Zephyrus, god of the west wind, successfully established Άγιος Κυρίλ/Saint Kirill (near today’s Adelaide, Australia) and the enormous colony of Ολυμπία/Olympia (today’s South Island of New Zealand)!

Now back to our story …

England entered the Indian Ocean relatively late, and did not enjoy any advantage over France or Andalusia, but the public relations effort of the English East India Company to court Liao was definitely top-notch. In 1641 Dr. Gabriel Boughton aboard a ship of the company entered the palace and cured the sick crown prince, quite positively impressed the Liezong (烈宗, lit. “Strong/Staunch Ancestor”) Emperor for people from this tiny island country.

However - it is often a “however” that people fear -

The following chain of events grew out of the control of the English.

After the Liao gained control of the Strait of Malacca in 1657, the pirate activities on Indian Ocean became even more rampant. Due to the compulsory taxation of customs carried out by the Liao Bureaus of Foreign Shipping everywhere, the smuggling business of spices, porcelain and tea grew increasingly profiting and the news even drew European pirates to come and try their luck -

Until the major incident that took place off the Ceylon coast that night, on December 15th 1659, almost completely ruining the effort of the English East India Company to court the Liao emperor. The commissioners of the French East India Company in turn threw their hats off to celebrate, and the event led to the first ever mission Mahakhitan sent to European countries –

We will come to talk about the details of this grave incident, and the tides it turned on the restless surface of the Indian Ocean.

This piece is actually an atlas disguised as an article … I didn’t think of any better way to fuse the history of trade part and the world atlas part, so let’s take it this way for now. I’ve been too sick to refine the wording recently, so the content mostly came from the notes I’ve been taking, please excuse me.

024 – 沸騰的海洋:17世紀的印度洋貿易概述,附大量地圖

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Europeans discovered the southern Indian Ocean sea lane in mid 16th Century. Instead of the route taken by the voyagers before them, now European merchant ships could skip stopping by East Africa and the Indian coast and directly take the west wind once they passed Cape of Good Hope until arriving in Java and the Spice Islands through the open waters near Australia.

The main (red) and secondary (cyan) Indian Ocean trade routes – just like in the history of OTL.

By mid 17th Century, such an outlook was formed: the “main” sea route of the southern ocean almost completely belonged to the galleons of Europeans, whereas the coastal trade was conducted by the merchant ships of the countries that bordered the Indian Ocean.

Trade in the Mediterranean used to experience ups and downs several times during the 16th Century, but the course of history was proved difficult to resist. During 1580-1600, the Mediterranean trade route finally withered, with Rome, Tianfang (Arabic Kingdom under the House of Hashemites) and the Caliphate (formerly Kingdom of Iraq, Liao's ally for three centuries) being the ones that were hit the hardest.

The inland routes, due to their completely different destinations, managed to remain free from being directly affected. The Liao Central Capital city, after the sufferings brought by the civil war in early 16th Century, was in decline, but the Afghan trade lane was still enjoying prosperity, allowing this city to keep its status as the regional business hub. The entire Persian-Afghan trade lane did not experience decline until 1750.

However, what will entertain us today would still be stories of the boiling Indian Ocean in the 17th Century.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

The spice smuggling wars all over the Indian Ocean had begun in as early as the 1580s. One side of the “battles” were the state of Liao that, with her ten Bureaus for Foreign Shipping, intended to consolidate her monopoly over the trade in the east, while the other side were the newcomers in the Indian Ocean that wanted to directly engage in the trade of spices such as England and the Netherlands.

Liao had realised the Europeans’ southern sea lane was causing trade losses, and began to set her own plan in Jinzhou (the generalised name in Indian languages for the Malay Peninsula, Kalimantan and Sumatra). The newly built Liao navy started to be stationed at the pre-existing Khitan plantations and trade points in southern Kalimantan from 1620. Local agencies of the Bureau for Foreign Shipping were established by the Liao government which, while attempting to build the region into a transit centre, also tried to directly tax Europeans who conducted trade along the nearby major routes. The intention was to block one end of the Europeans’ main trade routes and force them to stomach the taxation by the Liao Bureaus of Foreign Shipping in Jinzhou and Johore if they wished to do business in the Spice Islands, China and Japan.

But on the high seas of the 17th Century, any attempt to reach trade monopoly could not have been too successful given the technological level back then. Ming sea trader groups and Liao’s very own sea traders themselves were massively smuggling to any buyer that had gold in their pockets. The Europeans also had their own alternatives other than Mahakhitan – the Kingdom of Pasai controlling the Strait of Malacca and the Kingdom of Chola located in the south of the South Asian Subcontinent. They became the most difficult competitors once they escaped from Liao’s sphere of influence.

A few other things that need to be mentioned since the beginning of the 17th Century.

Cotton cloth from India became the desirable export in trade with Europe. Every year over one thousand tons of silver flocked to Liao and Chola, rendering the silver crisis of Ming much more severe in this timeline and indirectly causing an earlier collapse of it.

Climate during the little ice age led to multiple droughts and famines from Wuchuan Circuit to Shanyang Circuit in early 17th Century. The people hit by these disasters emigrated in large scale to Liao’s Jinzhou. Some ended up in the more distant southern continent – Videha (today’s Australian west coast).

The development of Videha was mostly steered by private trading firms from Shanyang Circuit. In 1643, some Khitan herdsmen found gold mines one thousand li inland, and the news further drew more immigrants. By 1649 when the General-Governor’s Office of Videha was established, the local Liao population was approximately twenty thousand households.

Situation around the Liao in mid 17th Century (uncompressed map: https://mega.nz/#!l1omwSrQ!xGBXqqvGedt3n0_kYI2F3wkDv_ndXlajfBa1_hQgED0).

Distribution of religions in mid 17th Century (uncompressed map: https://mega.nz/#!Y0oSCSbb!JFuVRAWqwyTUf1NSNK_BIzy6V8Wt3Hl8woCtTgjvero).

Seeing the Liao setup in Jinzhou and Videha, Chola and Pasai began to feel grave danger. Around 1640, as the response to Liao’s build-up in Jinzhou, Chola leased some ports along the Coromandel and Malabar coasts to countries like England, France, Andalusia and the Netherlands, allowed these Europeans to build trade stations and forts along the coast of southern India, and bought firearms in bulk in hope of countering Liao with military support from European countries.

The subsequent counter-strike Liao launched against the Chola-Pasai alliance in turn shocked the entire Indian Ocean region as well as Europe - in 1653, an imperial edict was sent to the court of Pasai, in which the Liao emperor listed from Pasai’s betrayal of the alliance one hundred years ago to the current misdeed of the Sultan of Pasai as he connived with the pirates that were hiding along the coast of Sumatra, signaling an ominous unfolding of events between the lines.

In the war that followed, the Liao navy imposed a blockade on Sumatra and Malacca for two years, the Pasai land forces as a result were trapped in the Malay Peninsula and were then defeated by the army of Liao’s ally, Dacheng. Trade through the Strait of Malacca was cut off, almost bankrupting the English and East Roman East India Companies.

Pasai and Chola begged for surrender in May, 1657 and Liao regained control of the coasts of the strait. Twenty years of Liao expansion seemed to have completely choked the trade route of the Europeans, at least on the map.

Apart from feeling the shock, European countries still desperately tried to maintain their relationships with Liao - who would go against profit after all? Most European countries shown in the following maps had trade stations in Liao’s Southern Capital and Suluo (today’s Surat). Among them, France and Andalusia had the closest trade partnership with Liao, and enjoyed the good impression of being “submissive” in the eyes of the Liao emperor.

Below are the maps of the world’s global empires in 1660:

France ITTL gained Brazil (referred to as “Côte de Brasil française”), some isles along the African coast and the Indian Ocean, as well as a foothold in New Guinea. It maintained a decent relationship with Mahakhitan and firmly grasped an entering ticket to the Spice Islands.

…… Spain ITTL, on the other hand, did not achieve unification and remained as Castile, with more or less a similar set of colonies.

An independent Catholic Kingdom of Andalusia, fruit of a western European crusade back in the 13th Century. Her colonies included the Mississippi River basin in the New World (the major city Nova Cordova is near New Orleans IOTL). She was always at odds with the Kingdom of Castile, and an ally of France. Her territory in Guinea was notorious for slave trade, and she also had footholds along the Indian coast and near the Spice Islands.

This kingdom of red tiles and white walls in sunlight has a very exciting face. Her emblem was a crowned lion between the Pillars of Hercules.

Oh, and she has another trade post, San Salvador of the Andalusian East India Company (today’s Keelung).

England unified the British Isles, and took some land similarly as she did IOTL, but she was a late-comer to the Indian Ocean region.

Also noteworthy: the Scottish aristocrats rebuilt the Kingdom of Scotland (could also be called Scotia Nuadh/New Scotia) in the New World, with the capital being Dùn Èideann Ùr/New Edinburgh (today’s Boston). Major cities include Lodainn Ùr/New Lothian (today’s southern end of the island of Manhattan) and so on.

Umm… a Catholic Duchy of Holland/the Netherlands, also pretty aggressive in terms of expansion overseas – she had a larger-than-IOTL Dutch South American colony (called Nieuw Holland/New Holland, seriously, how does this place resemble your Seven Provinces, I say).

A Denmark that never let go of Norway, and under the glory of the ancestors re-colonised Vinland, land of the best wine in legends.

The most exciting one should be our East Rome. Her Hellenic renaissance had countless stories to offer in the first place. After the decline of the Mediterranean trade route, Rome started to further explore in the West Indies and East Indies.

The empire’s West India Company established two colonies, Νέα Νάξος/New Naxos (today’s Winward Islands and Leeward Islands) and Ἀμαζών/Amazones (today’s Venezuela and Guyana).

The empire’s East India Company on the other hand used Νέα Ικόνιον/New Ikónion (today’s Port Nolloth of South Africa) as a springboard for further exploration, and with the divine help of Zephyrus, god of the west wind, successfully established Άγιος Κυρίλ/Saint Kirill (near today’s Adelaide, Australia) and the enormous colony of Ολυμπία/Olympia (today’s South Island of New Zealand)!

And how can we forget about our Great Liao.

(Caption: "Great Central Hulizhi Khitan State - Great Liao State,

and overseas prefectures, counties and tributary states,

13th Year of Mingshao/明紹/Bright Restoration";

Hulizhi is modern Pinyin for 胡里祇, which was in turn likely an ancient transliteration of the original Khitan word for "Liao=遼=broad" - there are other explanations of Liao's original full name - some argue all variations basically meant "State of the Heavenly People", including the "Khitan" component, but let's set it all aside here...)

(Caption: "Great Central Hulizhi Khitan State - Great Liao State,

and overseas prefectures, counties and tributary states,

13th Year of Mingshao/明紹/Bright Restoration";

Hulizhi is modern Pinyin for 胡里祇, which was in turn likely an ancient transliteration of the original Khitan word for "Liao=遼=broad" - there are other explanations of Liao's original full name - some argue all variations basically meant "State of the Heavenly People", including the "Khitan" component, but let's set it all aside here...)

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Now back to our story …

England entered the Indian Ocean relatively late, and did not enjoy any advantage over France or Andalusia, but the public relations effort of the English East India Company to court Liao was definitely top-notch. In 1641 Dr. Gabriel Boughton aboard a ship of the company entered the palace and cured the sick crown prince, quite positively impressed the Liezong (烈宗, lit. “Strong/Staunch Ancestor”) Emperor for people from this tiny island country.

However - it is often a “however” that people fear -

The following chain of events grew out of the control of the English.

After the Liao gained control of the Strait of Malacca in 1657, the pirate activities on Indian Ocean became even more rampant. Due to the compulsory taxation of customs carried out by the Liao Bureaus of Foreign Shipping everywhere, the smuggling business of spices, porcelain and tea grew increasingly profiting and the news even drew European pirates to come and try their luck -

Until the major incident that took place off the Ceylon coast that night, on December 15th 1659, almost completely ruining the effort of the English East India Company to court the Liao emperor. The commissioners of the French East India Company in turn threw their hats off to celebrate, and the event led to the first ever mission Mahakhitan sent to European countries –

We will come to talk about the details of this grave incident, and the tides it turned on the restless surface of the Indian Ocean.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

This piece is actually an atlas disguised as an article … I didn’t think of any better way to fuse the history of trade part and the world atlas part, so let’s take it this way for now. I’ve been too sick to refine the wording recently, so the content mostly came from the notes I’ve been taking, please excuse me.

Last edited:

Update!

Two things:

1. Feel free to suggest anything I might have got wrong (yeah I know there's a letter missing from the religion distribution map...): the Dutch, Danish, Scottish Gaelic, Greek names for example are from Google Translate and effort of pin-pointing Wiki entries in other languages, so they could be wildly inaccurate for all I know. The French "Red Wood Coast" is also tricky.

2. The next chapter is both very hard to translate and long, so be prepared to wait for longer than say 2 weeks...

Enjoy (I'm under the impression that the general readership here can relate to maps a lot more LOL)!

Two things:

1. Feel free to suggest anything I might have got wrong (yeah I know there's a letter missing from the religion distribution map...): the Dutch, Danish, Scottish Gaelic, Greek names for example are from Google Translate and effort of pin-pointing Wiki entries in other languages, so they could be wildly inaccurate for all I know. The French "Red Wood Coast" is also tricky.

2. The next chapter is both very hard to translate and long, so be prepared to wait for longer than say 2 weeks...

Enjoy (I'm under the impression that the general readership here can relate to maps a lot more LOL)!

Last edited:

How OTL southern Fujian became independent state of Min (闽/閩)?

Random in-game unfolding. It happens. In case you didn't know, the original author Kara based this on a continued CK2-EU4 (and now towards Vic2) timeline.

People on Zhihu (where this series is originally published) asked similar questions and basically Kara said we could regard Min ITTL as the result of a successful pirate-warlord (think Zheng Zhilong) uprising by exploiting the instability of Great Ming.

I have to say—how come Kara never took out the Southern Indian states? Map’s fugly.

Do I detect an independent basin of Mexico and Maya/central America? Is there overlap with a certain other TL?

I'll ask Kara later~

I must assume that the Mesoamericans survived by playing off the European powers against each other. Whenever Castille would try to invade, the natives would suddenly have steel weapons, horses, and gunpowder from France and Andalusia. Whenever France would try to invade, all of a sudden Dutch and English arms would be flowing freely.

This didn't happen OTL, as there was a great empire in Mesoamerica and it was conquered shortly after contact. And the only power that could help the natives wasn't interested in what was happening so far west. In a world with more equal competing powers in the New World, it could stand to reason that the natives of Mesoamerica were able to retain independence. Of course, they would probably get conquered in the 19th century like many African states who had survived like that did.

This didn't happen OTL, as there was a great empire in Mesoamerica and it was conquered shortly after contact. And the only power that could help the natives wasn't interested in what was happening so far west. In a world with more equal competing powers in the New World, it could stand to reason that the natives of Mesoamerica were able to retain independence. Of course, they would probably get conquered in the 19th century like many African states who had survived like that did.