Belgium's ethnic cleansing of Walloons is considered a Heritage Point of Controversy, so it doesn't look good...At least he's being honest. What makes Diversitarianism such a dystopian horror is that a government can get away with just about any atrocity, and when you pile the evidence to the skies in front of them, they can reply, "That's just, like, your opinion, man" or "Agree to disagree." (What about actual genocide? According to the internal logic of Diversitarianism, blasting a color out of the Rainbow forever should be the one unforgivable crime. Is it seen that way, or is it just another Heritage Point of Controversy to play with?)

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Look to the West Volume IX: The Electric Circus

- Thread starter Thande

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 38 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

322 World map 1927 323 324 325a 325b 27 ConclusionCan the Combine actually lose territory before the Last War of Supremacy? In dystopian fiction AH timelines featuring a main Antagonist nation, it never generally tends not lose territory e.g the Draka or DoD’s USA until terminal collapse, but since it is scattered across multiple continents, it shouldn’t be too hard to start a rebellion in the Kongo Kingdom or elsewhere

EDIT: See above clarifications

EDIT: See above clarifications

Last edited:

I mean if the hints are anything to go by Zone 1 at the very least gets glassed.Can the Combine actually lose territory? In dystopian fiction, the Evil Empire never loses territory e.g the Draka or DoD’s USA, but since it is scattered across multiple continents, it shouldn’t be too hard to start a rebellion in the Kongo Kingdom or elsewhere

You'll get more (and more polished) material if you buy the published volumes listed in the first post of this thread, but the original draft is still available starting here.Has there been any major map changes?

Also I wish to start the timeline but where do I go? Do I have to buy it or is it free somewhere?

Thande has a map thread in SLP but due to site rules, it is difficult to see the full image unless you are a member over thereYou'll get more (and more polished) material if you buy the published volumes listed in the first post of this thread, but the original draft is still available starting here.

This isn't dystopian fiction, it's a timeline by thande. The Combine gets no magical genre immunity.Can the Combine actually lose territory? In dystopian fiction, the Evil Empire never loses territory e.g the Draka or DoD’s USA, but since it is scattered across multiple continents, it shouldn’t be too hard to start a rebellion in the Kongo Kingdom or elsewhere

My bad - I should have said “ AH timelines featuring a main antagonist nation” instead. Added clarifications to the post. Does that make more sense?This isn't dystopian fiction, it's a timeline by thande. The Combine gets no magical genre immunity.

Last edited:

All the mentions of local Buddhists in Jushina/Panchala makes me wonder if the Chinese are very much pushing Buddhism over Daoism and Confucianism in this dynastic cycle.

How very unlike governments IOTL…At least he's being honest. What makes Diversitarianism such a dystopian horror is that a government can get away with just about any atrocity, and when you pile the evidence to the skies in front of them, they can reply, "That's just, like, your opinion, man" or "Agree to disagree."

Seriously, I find Diversitarianism unutterably weird in many ways, but the weirdest part isn’t that they do this stuff, it’s that they do it openly. Your country teaches that we were the baddies in a war a hundred years ago? Well, of course they do, and so they should, just like we teach the opposite. Whereas OTL, its often more like “actually, you were the baddies, so you can just shut up.”

315

Thande

Donor

Part #315: Silence Falls

“WHAT D__S ____TISM MEAN IN THE TWEN________ST CENT__Y?

DIVERSIT____ M__NS WAR!

SPEAK____ AJMUS JUL_______CP FOR NE_______CUT

Hear him ta_______iences in P______t and _____

MARCH TOGE___ O THE F___TURE UNDER NO FLA__”

- Decayed and slightly vandalised sticker seen on Callaway Road, Fredericksburg, ENA.

Photographed and transcribed by Sgt Bob Mumby, December 2020

*

(Lt Black’s note)

While Dr Wostyn retrieves his notes on the Toulon Conference from where Sergeant Ellis…put them, it’s high time we covered developments in Societism after the death of Alfarus. This was actually one of the first talks we recorded, but some people have opinions on chronology…

*

Extract from recorded lecture on “History’s Blankest Page” by Dx Elizabeth Pickering, recorded October 18th, 2020—

No matter the strength of our Iversonian convictions, there is always something a little transgressional about discussing Societism. (Subdued audience reaction) You’ll have seen that some of my fellow lecturers have even had threats to disrupt their talks.[1] However, no such disruptions seem to have materialised here and now. And why? Not because I am so intimidating, I think. (Audience chuckles) Rather, it’s just that the mysteries of what happened following the death of Amigo Alfarus are so compelling that even the most Soviet-minded among us cannot help but desire to hear the latest theory, the latest speculation.

For a man who became such a dominant figure of the early twentieth century, Rodrigus Alfarus is a remarkably indistinct asimcon image. Most of this was due to his own design, of course. It was in his interests to ensure that no records survived of his early life, of when he came to believe in Societism, of when he became the de facto dictator of the Combine. Several mutually-contradictory versions of his backstory, each replacing the last, were put out by the Biblioteka Mundial just in his own lifetime, and they have only multiplied since then. The history of Alfarus changed like a chameleon to match changes in the world around him. In the dark days of the plague, Alfarus was the son of a visionary doctor. Earlier, when the early Combine was fighting the IEF, Alfarus was descended from the man who inspired the Duc de Noailles’ son to defect to the UPSA, whose revolution could then still portrayed positively in selective Societist propaganda. About the only background which the Biblioteka did not connect him with was the one which a tentative majority of biographers in the free world believe was his in truth; that he was a career soldier, possibly from a line of career soldiers. But such speculation is fruitless.

You might object to me describing the Silent Revolution as ‘history’s blankest page’. I’ve just talked about how Alfarus’ life became retrospectively shrouded in mystery from the beginning. Another good example, and a parallel for many things I’ll be discussing, is the Jacobin Revolution of 1794 in France. The Revolution was already a complex process to begin with, unprecedented radical forces interacting with an ancient and bewilderingly byzantine ancien regime. But this became all the more confused when successive waves of the revolution turned on their precursors and attempted to expunge them from the record, making themselves the sole arbiter of Latin republican purity. Until, that is, the next group of men at the head of an angry mob came along and consigned them to the phlogisticateur or the chirurgien in turn.[2] Lisieux himself, fearing the symbol of the martyred Le Diamant as a threat, attempted to suppress his document La Carte and replace him with the conveniently simpler figure of L’Épurateur.[3] Thus he tried to write out of history the very man whose martyrdom had ignited the Revolution, a task only slightly less ambitious than his predecessor Robespierre’s abortive attempt to commission a version of the Bible with all the references to God removed.[4]

I could go on with other examples. But what I hope to convince you is that the case of the Silent Revolution of 1938-41 was different, and more profound, than any of the attempts to suppress recent history that had taken place before it. Or since, for that matter. Take my example of revolutionary Paris in the 1790s first. The Jacobin Revolution was taking place in a very different world. France had not a toise of railways to her name and steam engines were barely known outside of M. Cugnot’s workshop of curiosities. Though remaining legally a decentralised feudal state, in terms of political discourse France had become increasingly centred on Paris, especially since the days of Louis XIV. Thus the successive waves of Revolution were not roaring across the country, for the most part; they were merely toppling regime after regime in Paris. The Vendéan revolt was only the most successful illustration of how large parts of the country were left behind, and shocked, by the excesses of Jacobinism in Paris. There were also far fewer newspapers, far fewer printers producing pamphlets such as Le Diamant’s La Carte. When we say that Lisieux was able, in part, to suppress and rewrite the earlier history of the Jacobin Revolution – the numbers of books he had to burn, the number of prominent people he had to have sent to his work camps – they were far fewer than we might picture in today’s connected society. The death of Le Diamant was not broadcast by Motoscopy to the whole world. We might picture Lisieux as running a country with a dictator’s iron grip, but his control only approached modern notions of totalitarianism in the environs of Paris. You may have heard of the Jacobin doctrine that ‘to hold the heart is to hold the nation’ and perhaps now you see the context of this.

Very well; but what about Alfarus’ early life, my other example? Was that not history’s blankest page? No. Whatever Alfarus was before the turn of the twentieth century, it is clear he was not a prominent figure. Suppressing records of his life, of those who had memories of him, was not a difficult task for one of sufficiently ruthless mind. We know how easily skilful propaganda can warp the perceptions of people even about a popular public figure they have grown up seeing, but Alfarus had no such preconceptions to suppress. Even when he became de facto dictator he was initially not well known to the Societist public, preferring to remain in the shadows.[5] It was only in the 1920s that it became clear to the average Amigo or Amiga that, behind the Zonal Rejes supposedly in charge, it was the Kapud of the Celatores who was really calling the shots. Not that many would openly speak of him.

It was this tendency on Alfarus’ part that probably made the epistemic purges of the Silent Revolution possible at all, but it remained a daunting feat. One consequence of Alfarus gradually purging other early Societist revolutionary figures, and having them removed from the records by the Biblioteka, was that eventually the Combine historical narrative vaguely implied that Alfarus himself had been single-handedly responsible for every policy, every move, every victory during the Pandoric Revolution and the war against the the IEF. This meant that when the K.a.K. eventually turned on Alfarus’ legacy as well, they had to confront the idea of who to attribute all of this heroic narrative to. The end result was mostly presenting an even vaguer, nebulous account which implied that the Revolution and early victories had been an anonymous tide of historical inevitability, and that the forces of the nations arrayed against the Societists had spontaneously collapsed under their own contradictions, rather than being defeated either by the heroic Alfarus or whomever had actually commanded forces against them. This may actually be the most poisonous and dangerous legacy of the K.a.K. – but I’m getting ahead of myself.

In 1936, ten years had passed since Alfarus had led the Combine to victory in the War of 1926. (Audience reaction) That’s how it was seen. During the Black Twenties, the Combine had become a target of envy of many, firstly for remaining at peace during the war, and secondly being a source of innovation in the fight against the plague pandemic. To this was added military victory in 1926. It was quite unlike anything Pablo Sanchez would have supported, of course, but by this point that was immaterial. The point is that the Combine recruited many cadres of Societist true believers across the nations in the wake of these successes, and Alfarus’ position seemed untouchable.

But, as I said, now ten years had passed. We don’t know Alfarus’ exact age, of course, but the general consensus is that he was born somewhere around 1865. By that estimate he was, perhaps, seventy-one years old when he died. At that point, his position of dominance within the Combine had begun to show cracks. There were several factors involved, which would go on to manifest themselves as being associated with distinct factions within the Black Guards.

First of all, who were the Black Guards? As with many names of historical significance, it was not a name of their choosing, but one applied to them pejoratively by their enemies. They were certainly not a military organisation, and not in the same way that the Celatores merely unconvincingly denied being one. The Black Guards appear to have begun as a range of different secret societies within the vocational Akademiae which the Combine had set up for training its amigos and amigas in the roles determined for them by Rajmundus Olajus’ so-called meritocratic tests.[6] One of Alfarus’ defining characteristics was his childlike faith in the veracity of these tests, which in reality were flawed and outdated at their best and deliberately-rigged utter nonsense at their worst. Nonetheless, Alfarus would turn even on his oldest supporters if they dared criticise a single word of Olajus ‘perfect’ system, and even his wife – Madame Alfara as she is often, but inaccurately, known – was unable to reason with him on it.

Frustration with the obvious problems with the tests was likely one of the major factors behind the formation of the original secret societies which became the Black Guards. Young boys and girls assigned to particular vocations by the tests, vocations for which they were sure they were unsuited, would complain together in secret and then begin to plot subversion. None dared make a move while Alfarus lived, however. Though not prone to personality cults and not deliberately making himself a public figure, Alfarus remained a looming shadow over every Amigo or Amiga in this period. Remember that for the young people, they could not remember any time before he held absolute power. Some feared him for the rational reason that he enjoyed the loyalty of the armed Celatores who could suppress any revolt, but many more had begun to see him as something more akin to the ‘evil eye’, a supernatural presence that was always watching. It was this association that would lead to the Kaekokulus or Blindeye symbolism later on, but again, I’m getting ahead of myself.

Nonetheless, as time went on various groups of proto-Black Guards came into contact with each other and gradually became a more open movement. In so doing, they learned that there were a variety of other factors behind the resentment of different groups, beyond frustration with the flawed testing process. The two main strands of opinion in the Black Guards were largely defined by race or national background, much as any good Sanchezista might be horrified at the thought. (Audience laughter)

Firstly, there was the group that was increasingly disenchanted by how much they knew the Combine had moved away from Sanchez’s initial goals and values. One might wonder how they knew that, given how tightly controlled the discourse in the Combine was, but you must remember that Alfarus was an advocate of Doblizi Pensarum, or Dual Thought. Essentially, this meant that children were taught how the Combine should be, such as the idea that there should be no armed Celatores and that the Zonal Rejes should rotate between Zones, while also acknowledging the reality that this was not happening – attributed to ‘temporary measures while some bandit regimes remain un-suppressed’. In other words, so long as nations existed, the Combine might have ambitions to build true Societism, but would remain a military dictatorship under Alfarus’ thumb. This first faction of Black Guards consisted mostly of conceptual Meridians or ‘Firstslain’, especially Platineans, who were becoming impatient with this and began to believe that Alfarus was deliberately holding the progress of Societism back for his own selfish reasons.

The second major faction of Black Guards was dominated by non-Meridian Societist Amigos and Amigas. There were two main groups of these in turn – Nusantarans and Africans. The precise aims of the groups different somewhat, but both agreed that Alfaran Societism was flawed because it did not truly place different races and cultures on the same level. Under Alfarus, Javanese gamelans were destroyed while the Platinean guitar remained. These people were still doctrinaire Societists, you must remember. Mostly, they did not so much object to their own ancestral cultures and languages being annihilated as complain that the same attitude was not being fairly applied to residual Meridian culture. (Audience murmurs) The African group mostly had similar views to the Nusantaran group, but there was the additional complication that Karlus Barkalus still effectively ruled the Societists in Africa. They were certainly not as independent from Alfarus as the Grey Societists in Danubia and, increasingly, the Eternal State, but Barkalus’ longtime presence as Prokapud meant that the Africans were familiar with the idea of an alternative to Alfarus’ absolute power. There was no similar figure among the Nusantarans, who remained fearful of reprisals from the Celator garrisons in their islands. Regardless, this strand of opinion among the Black Guards was the beginning of what became known as the Konkursum ad Kultura or KaK, an accusation that the Combine was treated as nothing more than the UPSA and Hermandad with a black coat of paint, and continued to discriminate against non-Meridian cultures. The KaK would become emblematic of the Silent Revolution, to the point that the two are almost considered synonymous.

Under Alfarus, deliberate mixing between Societist Zones was limited, haphazard and erratic. The extreme ideas of the Garderista faction from the early Revolution had been limited, in a typically Alfaran pragmatic move, to use as a threat. Rather than all children being taken from their parents and raised in randomised communal crèches, removing a child was used as a punishment to keep dissidents in line. Early on, crèches on the Garderista model were sometimes tried for these children (itself leading to many, rather horrifying, stories) but, more often, they were adopted by families elsewhere. In practice, due to the rebellious Nusantara and Africa, this mostly consisted of children from those regions being raised by Meridian parents. Much less often, the reverse was also true. After the reconquest of Carolina in 1926, Carolinian children – white, black and red alike – were often sent to Africa or the Nusantara to be raised, which may represent a belated recognition that the process was seen as one-sided and unfair.

Besides this movement of children, individual families were also sometimes encouraged to move to different parts of the Combine. Again, this was not a well-organised system but usually a series of abortive initiatives by various ambitious administrators. Regardless, these two factors combined helped ensure that the two factions among the Black Guards encountered one another and were aware of each others’ grievances. The contradictions might have averted cooperation, but both were impelled into cooperation when the disastrous ‘Oil Standard’ economic policy of Josephus Kalvus resulted in financial ruin for many ordinary Societist Amigos and Amigas. This stirred up public anger against Alfarus among many who formerly had remained loyal, and set the stage for what would become the Silent Revolution.

The first truly open Black Guards emerged a few months before the end of Alfarus’ life, though by this point (in 1936) he had suffered a stroke and the regime was effectively already being run by his wife. These Black Guards were careful not to do anything that might make them a target for the Celatores. They wore black shirts with Threefold Eye pins, black berets with the same, and black armbands with the same Threefold Eye. It would be hard for the regime to condemn an Amigo for wearing the symbols of Societism, even if the large number of them suddenly appearing in a regimented way, as though this was a uniform, might make the leadership nervous. It is easy to see where the pejorative nickname came from.

With the final passing of Alfarus, probably from a heart attack, in October 1936, the regime was in a quandary. Alfarus had held absolute power for so long, and eliminated all rivals, that any notion of succession planning had always seemed tantamount to treason. Madame Alfara, or Maria Vaska as we should properly call her, became de facto leader of the Combine simply because she had been acting in her husband’s name. Emilius Gonzalus, a senior Celator and hero of the War of 1926 (Audience reaction) from their perspective, that is…Gonzalus was named Kapud and successor to Alfarus. The third member of the ruling triumvirate was Markus Lupus, the last surviving link back to Pablo Sanchez. Actually, Lupus – then called MaKe Lopez – had only met Sanchez briefly when he had been a young man, and had worked more with Raúl Caraíbas, but the line between the two had been increasingly blurred for years. Regardless, Lupus was now eighty-seven years old and had little capacity to act in a leadership position, but he was held up as a symbol of legitimacy by Vaska and Gonzalus.

The situation continued to deteriorate for the next eighteen months. This is where the text of our history book truly begins to peter out, consumed by the chaos that was to follow. I’ve called this talk ‘History’s Blankest Page’ for a reason. Archaeologists might argue with me, speaking of their attempts to reconstruct ancient events from few, or no, records. But, as I said before about the Jacobin Revolution, we must put earlier ages of history on a different level to any period that took place after the proliferation of literacy and communication methods in the nineteenth century. A page of history, or should I say a stone tablet, from ancient Sumer, China or Egypt, might be blank because there were few records ever made and those have not survived – rather than because they were deliberately suppressed. The Jacobins did deliberately suppress and rewrite history, but they had a relatively small number of records and means of communications to control compared to a century later. Even in the early era of Societist control in South America, where there had been many newspapers and journalists before the Pandoric War, the Societists were aided by the fact that Monterroso had had many of them witch-hunted as part of Operation Víbora.[7] The independent press in the old UPSA, already hammered by the pseudopuissant corporations, had then been burnt down by Monterroso and was relatively easy to rebuild in a Societist image.

No, I call the Silent Revolution ‘History’s Blankest Page’ because it represents the most systematic, yet confused and contradictory, attempt to control the narrative of history from a position where there was already a large and interconnected system of communication propagandising to the ordinary Amigo or Amiga. We look at this page in our history book, and at first we might be fooled into thinking it is simply empty, like the lost pages from the ancient world that frustrate the ancient archaeologists. But then we try to turn the page, and we find that it is heavy and rigid in our hands, thickly slathered with layer after layer of error fluid, blanking out attempt after attempt to rewrite it.[8] Those archaeologists teach us about tells in the Near East, places where cities have stood for thousands of years, periodically burned and rebuilt on the old foundations until they rise up like mounds just because of how many versions of a city have piled on top of each other. They are a profound glimpse into the deeps of time, yet if we cut into the Silent Revolution’s blank page, we would find the same layer after layer of building, burning and rebuilding, yet all crammed into a period of a few years.

Because of this, you should take everything I say with a pinch of salt. (Audience chuckles) The great irony of the Silent Revolution was that the Black Guards inadvertently created one of the most Diversitarian events in history. (Audience murmurs) Many in the ASN want us all to disagree about history as much as possible, fearful of crypto-Societism entering merely through a commonality of experience. There are many fervent Diversitarians who deliberately try to create bones of contention where none can reasonably exist. (More audience murmurs) Yet the Black Guards created the opposite; an era when even the most absolutist and counter-Diversitarian epistemic philosophical position breaks down, for no-one could claim to know what ‘really’ happened. Don’t worry, I’ll get off contentious topics in a moment. (A few chuckles) Suffice to say that what I will tell you is not only my Diversitarian opinion, but informed guesswork I cannot truly defend even to myself.

One point that is inarguable – I think! – is that the goals of the Black Guards were inherently doomed before they started. It can be argued whom among the movement first came to that conclusion; it might well not have been Pedrus Andonius, though he was the one whose name eventually became associated with the ‘Indutiae’. As I have said, the two main factions within the young Black Guards were Platineans disenchanted with how Alfarus had moved away from doctrinaire Societism in reality, and Nusantarans and Africans who opposed the fact that cultures were not being treated equally within the Combine. That will inevitably be an oversimplification, but it goes some way to explaining the quandary that the Black Guards found themselves in.

Despite the martial name and uniforms, by definition the Black Guards had no military experience. They were drawn from Akademiae youths who had never held any weapon more dangerous than a kitchen knife, and were Societist true believers who thought of soldiers as merely state-sanctioned murderers and disapproved of the place the Celatores had de facto gained in society under Alfarus. The Black Guards, certainly the Platinean faction, wanted to get away from a version of the so-called Final Society which was a military dictatorship under the Kapud in truth. They wanted to demote the Celatores to a minor role or, in the views of many extremists, eliminate them altogether.

We must remember, these were young people with fervent political views. We see extremist positions in our youth even in democratic societies, and it is only through experience that they gain nuance. The Black Guards had been raised immersed in Societist propaganda, not exposed to contrasting views. Furthermore, as I said, that faction was dominated by Platineans, people from wealthy areas conditioned by life experience to think of their land as impregnable. Much of Alfarus’ success, and that of the early Societists in the Pandoric Revolution, had been attributed to popular relief that they had defeated the Anglo-American invasion of the Plate. (Audience murmurs) But the Black Guards were young. None of them had experienced those events at firsthand, and the argument was no longer compelling to them. It was easy for them to believe that talk of conflict with the nations was just an excuse for the Celatores to retain their power. Perhaps one outside influence they had been exposed to was a small but significant influx of people from the Eternal State, who might have brought stories of how the Janissaries had risen from a slave army to effectively control the Ottoman Empire for a time. There were certainly parallels to the Celatores. No matter how naïve it may seem to us, some of the Black Guards genuinely believed that they could eliminate the Celatores without having to worry about who would then defend them from an attack by the nations.

But even to those who believed this, the paradox should be obvious. The Black Guards could not fight effectively, while the Celatores could, and had all the weapons. How could the Black Guards possibly overthrow the Celatores? Some vaguely spoke of a mass mobilisation of the people to shame the Celatores into standing down rather than fire on their own families. Others imagined that if they could gain control of the Zonal Rejes, the Celatores would dutifully obey an order to move up their planned suicide or execution from eighty years hence to now. At the height of the period of chaos, some versions of these ideas seem to have been tried on a small and regional scale in some parts of South America. As I keep saying, records don’t survive, but we can imagine how successful – or otherwise – they were.

To the more intelligent Black Guards, it was obvious that it was simply impossible for them to confront the Celatores directly. Whether it was truly Pedrus Andonius who realised the unthinkable alternative, or if this has been misattributed to him, can never be known; for the sake of brevity, I will say that it was him. Andonius was of mixed Dutch and Nusantaran descent from the old Batavian Republic, darker-skinned in appearance and one of the Black Guards frustrated with the inequality of treatment under Alfaran Societism. He had plenty of reasons to hate the Celatores, who had burned villages and killed members of his family in crude and indiscriminate reprisals during their suppression of the people of Java. But Andonius was also a pragmatist in a sea of uncompromising extremists. Furthermore, his sister was married to the much older Prokapud Ignatius Kaelus.

Kaelus had served as a staff officer to Prokapud Dominikus during the War of 1926 and had since worked his way up through the ranks. He had obtained a position of influence, but had always been a critic of Gonzalus, whom he argued was overrated and had benefited more from luck than skill in the war. Markus Garzius agreed with him on this, though he would soon damn Kaelus as a traitor.[9] With the ascension of Gonzalus to the Kapud-ship and his presence as one part of the shaky triumvirate ruling the Combine after Alfarus’ death, Kaelus’ track record of criticism resulted in his being demoted to a sinecure in Patagonia by the vengeful Gonzalus. Kaelus feared that this was only the first step in a process that would end in his own convenient suicide, helped along by Gonzalus’ supporters. He needed a way out. Pedrus Andonius, via his sister Julia, gave him one.

Thus the unthinkable compromise was hatched through secret meetings. Again, this is largely speculative. Some have claimed that Andonius had a long-term Machiavellian plan, having Julia marry Kaelus in the first place to give them a way in to the Celator power structure, but the timescale makes this very unlikely. The vague consensus is that Kaelus was impressed by the intelligence and charisma of the young Black Guard, and took his proposals more seriously than he had originally intended to.

Broadly, this appears to be what Andonius proposed: to overthrow the triumvirate with the massed Black Guards and the help of Kaelus and a group of Celatores; to install Kaelus as Kapud but without the political power Alfarus had enjoyed; for the Celatores to continue to enjoy the privileges, but for them to return to the shadows and these privileges to become less openly acknowledged than they had in the late Alfaran period; essentially, for the Celatores to stay on the edges of society and the borders of the Combine, avoiding politics. At this stage, it seems highly likely that Andonius did not discuss the Black Guards’ other ideas about ‘reforming’ the Combine, or he would not have obtained Kaelus’ support. Kaelus had been loyal to Alfarus in life; he probably did not have strong opinions about what happened to his legacy after his death, especially after Maria Vaska had sided with Gonzalus against him, but most analysts believe he would not have supported the Black Guards’s demand for ‘de-Alfarisation’.

It is interesting to speculate, as an aside, about what might have happened if Alfarus and Vaska had been able to have children. Evidence from elsewhere in the world suggests that the Combine might well have become a de facto hereditary monarchy. Some might argue that the tendency for supposedly non-hereditary regimes to become hereditary ones is in line with Sanchez’s ideas of universals of governance, but I said I would avoid contentious topics. (Mixed audience chuckles and murmurs)

But that’s an irrelevant speculation. There was no such obvious successor to Alfarus, and the triumvirate grew more and more unstable as time went on. It was only the legitimacy granted by Lupus that avoided internal schism, and then Lupus finally passed away in late 1937. Vaska and Gonzalus attempted to rule alone whilst looking for another figure to bring into their regime, but things continued to deteriorate. Public uncertainty grew, as the economy continued to underperform the boom years seen in the nations. As much of the world embraced the Gold Standard after the Shock of 1934 and the Passau Conference, the Combine was left behind even after abandoning Kalvus’ economic policies. It’s true to say that the average Amigo or Amiga didn’t have much idea about what was happening in the nations beyond propaganda, but information gradually began to leak in.

Also, the cracks were beginning to show in the popular Alfaran state programmes, literally in the case of the Casa de Omnes Clases.[10] Always intended to be temporary, these plasterboard dwellings were now beginning to show their age, and yet the state lacked the funds needed to replace them. The Combine had also already cleared much of the most accessible forested lands in the former Brazil to offer farmland, and now public goodwill was beginning to run out. Vaska had traded for a while on both her connection to Alfarus and the fact that Julius Quinonus had made her the face of the Familista movement, connecting her with ideas of a primordial mother-goddess figure or with old Catholic ideas about the Virgin Mary. But that image was now wearing thin.

The final straw was when Vaska made an unusual error of judgement. She chose Markus Andonius (formerly MaKe Antunez) to be the new third member of the triumvirate.[12] I should say he was no relation to Pedrus Andonius, to add to the confusion; Pedrus’ name was a Neolatinisation of the Dutch name ‘Anthonius’ rather than Antunez. Andonius, like Julius Quinonus, had been an important member of the Familista movement in the early Combine and a critic of the Garderistas. It is, perhaps, natural that Vaska might turn to him given her own connections with that movement. Markus Andonius was also another older Societist with links to the broader movement before the Pandoric Revolution, reflecting a broader tilt towards cautious gerontocracy in the corridors of power. Many Societists who had fought in the Pandoric Revolution now feared the prospect of turning over power to younger people who did not remember it. Some thought that, lacking firsthand knowledge of the old regime, they would repeat its mistakes, or not take the threat from the nations seriously – which, in the case of at least some among the Black Guards, was true.[13]

But the real problem with Markus Andonius was not his age, but the fact that the people regarded his appointment as a patronising insult. MaKe Lopez, Markus Lupus, had been a half-Chinese Peruvian intellectual. MaKe Antunez, Markus Andonius, not only shared a name but a background with his predecessor. As far as the man in the taberna was concerned, the government was trying to fool the people into thinking there was an artificial continuity, believing that the average Amigo wouldn’t notice that Lupus had been replaced. One of my colleagues, David Freland, has argued that the Amigos and Amigas had gotten used to rather subtle propaganda rewriting of history from the Biblioteka Mundial, and now actually saw Vaska’s move as being unworthily obvious!

We don’t know if Vaska actually did intend what she was accused of, or if the public seeing Markus Andonius that way was an unintended and unforeseen effect. Regardless, the will was there for change.

While all this was happening, Pedrus Andonius had been working his way up through the informal ranks in the Black Guards, their hierarchy still secretive but their presence more open on the streets than previously. Again, there were probably many more people involved in this process, whose names have not survived due to the later rewriting, and we don’t know for certain that Andonius himself was involved at this stage, though it seems likely. One slightly more doubtful figure is Agusdina Rivaria (no relation to Legadus Rivarius from the War of 1926) who appears to have been the Black Guards’ contact with the Biblioteka Mundial. This institution has always been shrouded in mystery more than any other part of the Combine, precisely because it is the institution responsible for rewriting every part of its history, including its own. We do not even know when the Biblioteka was truly created.[14] A story circulates that Rivaria worked at the Biblioteka in a minor capacity and, perhaps through a romantic connection as Julia Andonia had used, was able to gain access to sancta sanctora such as the Grey Archive of banned, or ‘unprinted’, books.[15]

We cannot be certain how true this is, of course, but one argument is that Andonius was able to take control of the Black Guards thanks to Rivaria’s access to earlier revisions of history, which helped individual Guards track down exiled family members and the like. Naturally, Andonius’ control was never absolute, and there were many rival groups of Guards. But Andonius’ alliance, or ‘Indutiae’, truce, with Kaelus ensured that any attempt to oppose him was doomed to failure. Those rival groups tended to burn out on the fringes of the Combine when they tried to stand against the Celatores, as I said, during the chaos of the later period. This split ensured that it was the African-Nusantaran faction within the Black Guards that rose to prominence, with the Platineans being relegated to a secondary role due to their initial refusal to accept the compromise of the Indutiae.

There may also have been a Black Guard contact with the Universal Church, but that is less certain. The Church saw more changes during and following the Silent Revolution than any other Societist body, with its former core of Jansenist Catholicism stripped of specifics now abandoned in favour of a vaguer universalism. New scriptures would be penned from scratch, and the old edited Bibles would soon be suppressed alongside their unexpurgated counterparts, along with Korans and other works. Churches, officially referred to as ‘Templa’, would become more iconoclastic and non-representative in character, in part due to a desire to destroy icons that connected Vaska with the Virgin Mary, perhaps also due to the influence of Nusantaran Black Guards from Muslim backgrounds. It’s not clear if these changes to the Church were achieved by working with groups within the Church or by attacking it from outside, as this seems to have been more feasible than opposing the Celatores.

For now, all of that lay in the future. While Vaska’s regime began to crumble, Andonius and Kaelus had been secretly training Black Guards with the help of Kaelus’ Celatores. Kaelus took advantage of his exilic posting to Patagonia by establishing a secret camp – or rather secretly expanding an existing one – in Tierra del Fuego. This island, referred to as Zon14Ins1 by the Societists, had played host to the Finisterra prison camp for many years. Kaelus used his authority to take control of the camp as well, and many vengeful political prisoners were recruited to the cause. One was Rikardus Romerus, a former ally of Alfarus who had been exiled to Finisterra back in 1909 for daring to question the ‘perfect’ meritocratic tests that Alfarus had such faith in.[16] After almost thirty years at the end of the world, Romerus was embittered and all too eager to help the Black Guards overthrow what was left of Alfaran Societism. Indeed, some have suggested that the particular counter-Alfaran vehemence of the Silent Revolution was attributable more to Romerus’ influence, and that of other former political prisoners, than the Black Guards themselves. The elderly but vigorous Romerus, who had played a role in the early part of the Pandoric Revolution and had memories of eras that had now been rewritten by the Biblioteka, likely also contributed to Andonius’ sense of legitimacy in that sense.

Another possible relevance of the setting of the Finisterra camp is that the Black Guards may have been influenced by residual traces of the old Moronite colony. This is much more controversial, as generally it is believed that the Societists had already wiped out or transported the Moronites, with a few refugees influencing the practices of the Massilian nudist movement in France.[17] However, if any Moronites remained, they may have been partly responsible for a tendency towards...romantic heterodoxy among some of the Black Guards. The Silent Revolution period would see a brief explosion of such divergent practices, in contrast to the former Societist debate between Garderistas and Familistas in which the conservative and pseudo-Catholic Familistas had triumphed, and the latter would not be (partially) reasserted until the 1960s.

The first stroke of the Silent Revolution was made not by Andonius, Kaelus or the Black Guards, but by the regime, and against a different opposition altogether; it is not certain if Vaska had ever taken the Black Guards seriously as a threat. In April 1938, it was reported that a new aerocraft design, a prototype of the large aeroliners that would become popular later, had crashed while undergoing tests. Tragically, the accident had claimed the lives of both Prokapud Pedrus Dominikus and Legadus Julius Rivarius, two heroes of the War of 1926. (Audience reaction) Again, from the Societist perspective.

Initially, the people mourned, but then questions began to be asked. Friderikus Molinarius had passed away only six weeks earlier, ostensibly of a gastric complaint – whose symptoms were indistinguishable from arsenic poisoning. Dominikus had been retired while Rivarius was still a serving Celator, and it was unlikely that both would ride in the same experimental aerocraft together. Furthermore, the aerocraft had crashed in what we call Lake Maracaibo in Venezuela, a relatively small body of water to hit during a test flight, but one which would conveniently result in the wreckage sinking beyond its easy recovery.

We still don’t know if any of the suspicious deaths of high-ranking Celatores and other officials were actually incidental, or if all of them were truly part of a conspiracy. Of course, we must remember that Alfarus himself had had many rivals purged under similar circumstances. But Alfarus had enjoyed more public support, and also had a keen understanding of whom he could get away with having near-openly purged. Romerus represents a rare misstep, and one committed due to Alfarus’ fanatical belief in the meritocratic tests. It soon became clear that many at the time had opposed Romerus’ condemnation (which may be why it was commuted to prison for life), though reluctant to openly stand against the Kapud out of fear. But now, enough of these figures were still around to rally to a banner which Romerus also supported. And they did not fear Vaska or Gonzalus.

Indeed, it was this lack of fear and respect that led Vaska and Gonzalus to pre-emptively act in panic, trying to kill off potential opposition figures associated with Alfarus and battlefield victory before they could act first. In fact, many of these figures would probably never have openly opposed Vaska and Gonzalus, not out of respect but merely because they feared the prospect of a coup and open division undermining the Sanchezista message. But Vaska and Gonzalus’ less-than-subtle actions spread a climate of arbitrary worry that anyone could be next. Angry Celatores, blaming Vaska and Gonzalus for the deaths of Dominikus and Rivarius in particular, began seizing control of their barracks and refusing orders from their ostensible Kapud. Gonzalus desperately began appealing for Celator garrisons in Africa, Carolina and the Nusantara to come to Platinea and put down these abortive mutinies. It was into this environment – we think – that the Black Guards grasped their chance.

Our best guess is that Kaelus used the panicked recall orders from Gonzalus as cover to bring his own loyal Celatores, along with an elite group of Andonius’ Black Guards and some of the freed prisoners in better shape than others, back to Zone 1 and even into Zon1Urb1. While Vaska and Gonzalus’ eyes were on more plausible Celator opposition figures, Kaelus and Andonius staged a coup. We have no idea of the details; again, this is History’s Blankest Page. Some refugees did bring limited and garbled accounts over the following years, but they all contradict each other. One claim is that Romerus wanted to have Gonzalus and Vaska both stripped naked, publicly marched through the streets of the capital being flogged by young Black Guards, and finally burnt alive atop a bonfire of Olajus’ meritocratic test forms. Nightmarishly colourful through this image is, there’s no evidence Romerus ever suggested it. Andonius certainly didn’t do it. We believe his approach was more to have Gonzalus and Vaska quietly suffocated and buried in unmarked graves, give no official public statement of their fates, but simply begin gradually removing evidence of their existence from the record.

Any chance of the Revolution ending with that coup were soon dashed, though. We think this was probably due to too many of the Black Guards, and Romerus perhaps, impatiently wanting de-Alfarisation, as well as some rogue Black Guards rejecting the Induniae and openly attacking groups of Celatores. Thus the Silent Revolution entered its next phase, about which we can say very little. The ostensible Kapud Kaelus seems to have been murdered at some point, possibly by his wife Julia on Andonius’ orders, possibly because he was about to side with other Celatores against him, led by another War of 1926 veteran, Andonius Simonus. Yes, yet another Andonius. (A few chuckles) The Societists really need more names...anyway, Pedrus Andonius was also killed in one of the revolutionary phases, but we are not sure when – probably as late as 1940. There were several figures, or cabals of figures, who succeeded him, but the order is not clear. The extent of the fighting is also, well, not clear. You guessed it.

It is easy, in hindsight, to ask why no-one took advantage of this Societist internal weakness and infighting to try to reclaim lost territory for the nations, such as France invading Spain or the Empire invading Carolina. (Audience assent) The answer is simple, though it may be hard to believe. This is called the Silent Revolution for a reason; almost no-one outside the Combine even knew it was happening for a long time. Alfaran udarkismo, separating the Combine from the world economy as much as possible, no matter the consequences with the Gold Standard – it meant that there was little that could be discerned from economic analyses. So few travellers from the free world were permitted to see the Combine, and those only exposed to carefully artificially-constructed villages of bright-eyes Amigos...in this era even the intelligence services of the nations struggled to obtain reliable information about what was going on. There was some awareness of events in Africa and the Nusantara, and the Caribbean, but not in South America, a whole continent that was fully under Societist control. Oh, there were always a few refugees who made it across the border in Carolina, but they had little understanding of what was going on. Even if some in the Imperial government did suspect internal turmoil and a weakening of Societist control, this was still the era in which all feared a potential reprisal by rocket missiles carrying death-luft warheads, potentially even aimed at cities.

Of course, what did ‘Societist control’ mean now that the core of the Combine was close to civil war? The real motivation for the Black Guards to rewrite history was not merely revenge against Alfarus or a sense of ideological purity. It was because the great fear of the Societists, from the beginning, had been the idea that there could be divergent points of view, different opinions about what the best course was to build Societism. As soon as differences were acknowledged, true homogenised unity under doctrinaire Sanchezism became impossible. The solution was to rewrite history so that the current phase of opinion had, retroactively, always been in power. But with the rapid changes during the Silent Revolution, the Biblioteka rewrote it over and over and...and we have our blank page, rigid and heavy with layers of dried error fluid.

We think that the Revolution was resolved when Karlus Barkalus finally decided that, rather than merely sending his Celatores, he would return from Africa to South America after almost thirty-five years. Barkalus was now old, but in some ways he enjoyed even more absolute loyalty and power than Alfarus had. His control might be more debatable and transient in some parts, but he nonetheless controlled a vast swathe of Africa, huge portions of what the Societists referred to as Zones 10, 19 and 27. His successes would soon prompt African leaders to approach France for help, but that’s another story. And, of course, Barkalus had a vast and loyal army of locally-recruited Celatores, many of whom were too young to remember anything but his rule.

Barkalus’ Celatores were able to subdue the remaining opposition in South America, whether they be rogue Black Guards, rogue Celatores or a few true-believer loyalists to the vanished Vaska-Gonzalus continuity regime. There may even have been counter-Societist forces like Tahuantinsuya nationalists who had remained in secret, but naturally this has been suppressed even more vehemently than the rest. A story circulates that Barkalus took Agusdina Rivaria as his fourth wife but, again, there’s no proof of this.

Regardless, as 1941 dawned, things became clearer in the Combine. The Combine was, of course, ruled by the Zonal Rejes, who would rotate between zones – as they always had. There would be no special provisions for cases like Franziskus Borbonus in Zone 13, and there never had been. Borbonus might have just been executed, but in reality, obviously he had never been a Rej for four decades because his father had been King of Peru and had cut a deal with the early Societists.[18] The Rejes had always rotated. The position of Kapud was retained, though Alfarus was gradually transformed in the narrative, from de facto dictator, to a well-meaning but often wrong military leader, to one of several Kapuds in succession, to a vague evil presence and spy of the nations who had held the Combine back. The Universal Church would eventually use him as a stand-in for Satan, possibly one of Romerus’ final acts of revenge. It was this part of the Revolution that drove hardcore Alfarus loyalists like Markus Garzius to declare the new leadership deviationist and go into exile. Of course, the heterodox Societists in Danubia and the Eternal State were more than willing to accept such refugees.

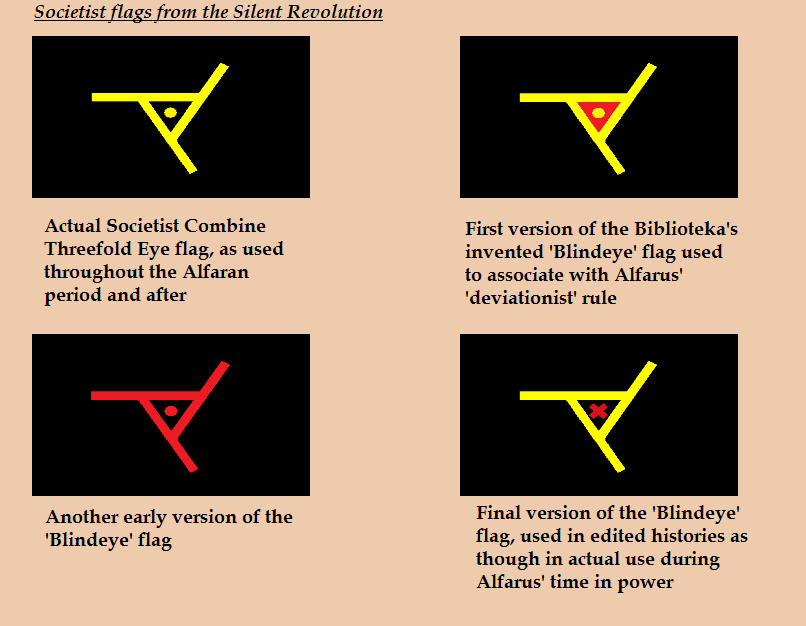

The latter-phase rejection of Alfarus, which had become doctrine by 1945, became associated with one of the more confusing rewritings of history by the Biblioteka. In reference to the idea that Alfarus had deviated from the true doctrine of Sanchezism and its Threefold Eye, Alfarus became described as Kaekokulus or Blindeye(s). This sometimes extended to him being portrayed as literally blind, but with a supernatural, demonic sight shining through a blindfold. In an even stranger consequence, history was rewritten to say that Alfarus’ supporters had used a deviant form of the Threefold Eye flag, allowing them to be conveniently labelled in airbrushed asimcons. Exactly what this deviant form was proceeded to change over time, after the Biblioteka apparently realised that their original idea of filling the centre triangle with blood-red was not easily visible in monochrome asimcons allegedly captured at the time. One can also sometimes find images of an Alfaran Threefold Eye being merely the same as a standard one but in red instead of yellow. Eventually, by 1952, the Biblioteka had settled on the central pupil of the Eye being replaced with a blind red X. Books were subsequently rewritten to associate any past deviationism and the influence of the evil Alfarus with this symbol, which had never existed in reality until that point. And, of course, the name ‘Rodrigus Alfarus’ and all its parts were banned. Rodrigus was such a common name that the government eventually compromised, insisting it be spelled ‘Rodrikus’ in future, reserving the old form for Old Blindeyes Watching You.

Ironically, it is because of these turn against Alfarus that the Kapud never displaced Lisieux as the symbol of ultimate earthly evil authority among the nations. Alfarus had been respected as well as feared among the enemies of Societism. When the Combine declined in subsequent years, it was natural to use the post-Revolutionary hatred of Alfarus as a Diversitarian tool to attack the Combine’s current leadership by making unflattering comparisons to Alfarus. ‘At least that man knew how to...’ and so on. That would not be possible if Alfarus himself was seen in a Lisieux-like capacity among the nations. Perhaps Markus Garzius contributed more to the Diversitarian cause than he had ever dreamed, or feared. (Audience reaction)

The final execution of the Revolution owed as much to Barkalus as Andonius or any of the Black Guards. Barkalus approved of the KaK movement, with plenty of resentment of his own for being judged more for the colour of his skin than his Societist values in the early days, and a new purge began of anything that could be accused of being connected with the old Meridian or ‘Firstslain’ culture. Naturally, people being people, this often led to fabricated evidence being used by a man to condemn his neighbour so he could seize his land, and so on. This would be a period of bloody and paranoid misery in the Combine. It would also not serve the cause of spreading Societism, for the inward struggle meant that Societist pushes in Africa and conspiracies in the Indian states began to shrivel and decline. It undoubtedly bought time for the nations to come to the understanding that would, for the first time, lead to a concerted position against the Societist threat.

And, in the end, the original cause of the Revolution would not be successful. Though the Zonal Rejes might be more empowered and might truly rotate for the first time, the office of the Kapud grew stronger than ever, recreating the power it had held under Alfarus but not under the hapless Gonzalus. Barkalus would hold the office of Kapud until his death in 1948 and would be succeeded without controversy by his chosen successor, a Nusantaran named Ismaelus Zuzandus. No matter what the Rejes did, real continuity of power would continue to rest with the Kapud and the Celatores, and a state founded on ideas of anti-militarism would continue to be a military dictatorship.

This was one contradiction, but it was a contradiction that Amigos and Amigas had always known. The deeper, more damaging contradiction was that all but the oldest and most recently conquered in their society had only ever known a world in which the shadowy Kapud Alfarus held absolute power, and loyalty to him was the only virtue that really mattered, no matter what the priests and the Sanchezista theorists said. Now, they lived in a world where Alfarus was the epitome of evil, and fervent opposition to his memory was the only virtue. No matter how sincere, it is hard to see how anyone could retain a simple faith in Societism having lived through this change. It is no surprise that men like Garzius, who for all their faults were honest and honourable in their own understanding of honesty and honour, refused to serve the new regime.

Furthermore, the Revolution damaged the Combine by attacking the very base of technological progression that had given it so many successes in the Black Twenties. Under Alfarus, providing scientists and engineers stayed quiet on political matters, they were safe and respected. Alfarus and his lieutenants had had some understanding of the fact that scientific research and engineering experimentation cannot always be expected to produce results merely in the face of threats. By contrast, the young and inexperienced Black Guards regarded these men and women as objects of suspicion, insufficiently ideological in how they approached their goals. Furthermore, Vaska’s family had been associated with the old chemical giant pseudopuissant corporations, and now they paid the price for that association. And finally, of course, the Black Guards were often recent graduates of Akademiae who held grudges against their former teachers. Purges of intellectuals from all these walks of life would have disastrous consquences for the Combine. In years to come, Societism would no longer be associated with the cutting edge of scientific development in the way that had made it admired by some during the Black Twenties. Or at least, not Combine Societism, for Danubia and the Eternal State offered less self-destructive alternatives.

And so the Combine entered a period of dubious self-introspection. The Silent Revolution and its conflicts were over, with who knows how many dead, but there was a sense of malaise, of lack of confidence of the future. The people of the Combine began to feel left behind, trapped behind udarkismo. Europe and the Empire had already begun to prosper in the 1930s, but now the revival of China and the creation of the Gold Standard led to a period of even greater global prosperity – and even greater social change. The Dirty Thirties gave way to the Naughty Forties, and suddenly Societism seemed like yesterday’s news...

[1] See Part #305, whose lecture was recorded chronologically after this one.

[2] See Part #20 in Volume I.

[3] See Part #54 in Volume II.

[4] In OTL Thomas Jefferson attempted something sometimes described as this, but rather more modest in reality, focusing only on the sayings of Jesus. It is possible that the project described in the talk never actually happened and something Jefferson (then serving as American minister to France in TTL) said was misattributed to Robespierre.

[5] See Part #290 in Volume VIII (also for the mention of the story of the painting of the empty room).

[6] See Part #265 in Volume VII.

[7] See Part #248 in Volume VI.

[8] ‘Error fluid’ refers to a similar substance to that known variously as Tipp-Ex, white-out, liquid paper, etc. in OTL.

[9] See Part #300 in Volume VIII.

[10] See Part #290 in Volume VIII.

[11] See Part #285 in Volume VIII.

[12] Previously mentioned in Part #208 in Volume V.

[13] This is similar to the OTL Soviet tilt towards gerontocracy from the 1960s onwards, with comparable motivations that the revolutionary generation feared handing over to one which did not remember life under the Tsar. There are also parallels with how UK politicians such as Margaret Thatcher were reluctant to hand over to generations who had not lived through the Second World War, believing that they would not take the threat of a resurgent Germany seriously.

[14] See Part #290 in Volume VIII.

[15] See Part #260 in Volume VII.

[16] See Part #265 in Volume VII.

[17] See Part #287 in Volume VIII.

[18] See Part #260 in Volume VII and Part #290 in Volume VIII.

“WHAT D__S ____TISM MEAN IN THE TWEN________ST CENT__Y?

DIVERSIT____ M__NS WAR!

SPEAK____ AJMUS JUL_______CP FOR NE_______CUT

Hear him ta_______iences in P______t and _____

MARCH TOGE___ O THE F___TURE UNDER NO FLA__”

- Decayed and slightly vandalised sticker seen on Callaway Road, Fredericksburg, ENA.

Photographed and transcribed by Sgt Bob Mumby, December 2020

*

(Lt Black’s note)

While Dr Wostyn retrieves his notes on the Toulon Conference from where Sergeant Ellis…put them, it’s high time we covered developments in Societism after the death of Alfarus. This was actually one of the first talks we recorded, but some people have opinions on chronology…

*

Extract from recorded lecture on “History’s Blankest Page” by Dx Elizabeth Pickering, recorded October 18th, 2020—

No matter the strength of our Iversonian convictions, there is always something a little transgressional about discussing Societism. (Subdued audience reaction) You’ll have seen that some of my fellow lecturers have even had threats to disrupt their talks.[1] However, no such disruptions seem to have materialised here and now. And why? Not because I am so intimidating, I think. (Audience chuckles) Rather, it’s just that the mysteries of what happened following the death of Amigo Alfarus are so compelling that even the most Soviet-minded among us cannot help but desire to hear the latest theory, the latest speculation.

For a man who became such a dominant figure of the early twentieth century, Rodrigus Alfarus is a remarkably indistinct asimcon image. Most of this was due to his own design, of course. It was in his interests to ensure that no records survived of his early life, of when he came to believe in Societism, of when he became the de facto dictator of the Combine. Several mutually-contradictory versions of his backstory, each replacing the last, were put out by the Biblioteka Mundial just in his own lifetime, and they have only multiplied since then. The history of Alfarus changed like a chameleon to match changes in the world around him. In the dark days of the plague, Alfarus was the son of a visionary doctor. Earlier, when the early Combine was fighting the IEF, Alfarus was descended from the man who inspired the Duc de Noailles’ son to defect to the UPSA, whose revolution could then still portrayed positively in selective Societist propaganda. About the only background which the Biblioteka did not connect him with was the one which a tentative majority of biographers in the free world believe was his in truth; that he was a career soldier, possibly from a line of career soldiers. But such speculation is fruitless.

You might object to me describing the Silent Revolution as ‘history’s blankest page’. I’ve just talked about how Alfarus’ life became retrospectively shrouded in mystery from the beginning. Another good example, and a parallel for many things I’ll be discussing, is the Jacobin Revolution of 1794 in France. The Revolution was already a complex process to begin with, unprecedented radical forces interacting with an ancient and bewilderingly byzantine ancien regime. But this became all the more confused when successive waves of the revolution turned on their precursors and attempted to expunge them from the record, making themselves the sole arbiter of Latin republican purity. Until, that is, the next group of men at the head of an angry mob came along and consigned them to the phlogisticateur or the chirurgien in turn.[2] Lisieux himself, fearing the symbol of the martyred Le Diamant as a threat, attempted to suppress his document La Carte and replace him with the conveniently simpler figure of L’Épurateur.[3] Thus he tried to write out of history the very man whose martyrdom had ignited the Revolution, a task only slightly less ambitious than his predecessor Robespierre’s abortive attempt to commission a version of the Bible with all the references to God removed.[4]

I could go on with other examples. But what I hope to convince you is that the case of the Silent Revolution of 1938-41 was different, and more profound, than any of the attempts to suppress recent history that had taken place before it. Or since, for that matter. Take my example of revolutionary Paris in the 1790s first. The Jacobin Revolution was taking place in a very different world. France had not a toise of railways to her name and steam engines were barely known outside of M. Cugnot’s workshop of curiosities. Though remaining legally a decentralised feudal state, in terms of political discourse France had become increasingly centred on Paris, especially since the days of Louis XIV. Thus the successive waves of Revolution were not roaring across the country, for the most part; they were merely toppling regime after regime in Paris. The Vendéan revolt was only the most successful illustration of how large parts of the country were left behind, and shocked, by the excesses of Jacobinism in Paris. There were also far fewer newspapers, far fewer printers producing pamphlets such as Le Diamant’s La Carte. When we say that Lisieux was able, in part, to suppress and rewrite the earlier history of the Jacobin Revolution – the numbers of books he had to burn, the number of prominent people he had to have sent to his work camps – they were far fewer than we might picture in today’s connected society. The death of Le Diamant was not broadcast by Motoscopy to the whole world. We might picture Lisieux as running a country with a dictator’s iron grip, but his control only approached modern notions of totalitarianism in the environs of Paris. You may have heard of the Jacobin doctrine that ‘to hold the heart is to hold the nation’ and perhaps now you see the context of this.

Very well; but what about Alfarus’ early life, my other example? Was that not history’s blankest page? No. Whatever Alfarus was before the turn of the twentieth century, it is clear he was not a prominent figure. Suppressing records of his life, of those who had memories of him, was not a difficult task for one of sufficiently ruthless mind. We know how easily skilful propaganda can warp the perceptions of people even about a popular public figure they have grown up seeing, but Alfarus had no such preconceptions to suppress. Even when he became de facto dictator he was initially not well known to the Societist public, preferring to remain in the shadows.[5] It was only in the 1920s that it became clear to the average Amigo or Amiga that, behind the Zonal Rejes supposedly in charge, it was the Kapud of the Celatores who was really calling the shots. Not that many would openly speak of him.

It was this tendency on Alfarus’ part that probably made the epistemic purges of the Silent Revolution possible at all, but it remained a daunting feat. One consequence of Alfarus gradually purging other early Societist revolutionary figures, and having them removed from the records by the Biblioteka, was that eventually the Combine historical narrative vaguely implied that Alfarus himself had been single-handedly responsible for every policy, every move, every victory during the Pandoric Revolution and the war against the the IEF. This meant that when the K.a.K. eventually turned on Alfarus’ legacy as well, they had to confront the idea of who to attribute all of this heroic narrative to. The end result was mostly presenting an even vaguer, nebulous account which implied that the Revolution and early victories had been an anonymous tide of historical inevitability, and that the forces of the nations arrayed against the Societists had spontaneously collapsed under their own contradictions, rather than being defeated either by the heroic Alfarus or whomever had actually commanded forces against them. This may actually be the most poisonous and dangerous legacy of the K.a.K. – but I’m getting ahead of myself.

In 1936, ten years had passed since Alfarus had led the Combine to victory in the War of 1926. (Audience reaction) That’s how it was seen. During the Black Twenties, the Combine had become a target of envy of many, firstly for remaining at peace during the war, and secondly being a source of innovation in the fight against the plague pandemic. To this was added military victory in 1926. It was quite unlike anything Pablo Sanchez would have supported, of course, but by this point that was immaterial. The point is that the Combine recruited many cadres of Societist true believers across the nations in the wake of these successes, and Alfarus’ position seemed untouchable.

But, as I said, now ten years had passed. We don’t know Alfarus’ exact age, of course, but the general consensus is that he was born somewhere around 1865. By that estimate he was, perhaps, seventy-one years old when he died. At that point, his position of dominance within the Combine had begun to show cracks. There were several factors involved, which would go on to manifest themselves as being associated with distinct factions within the Black Guards.

First of all, who were the Black Guards? As with many names of historical significance, it was not a name of their choosing, but one applied to them pejoratively by their enemies. They were certainly not a military organisation, and not in the same way that the Celatores merely unconvincingly denied being one. The Black Guards appear to have begun as a range of different secret societies within the vocational Akademiae which the Combine had set up for training its amigos and amigas in the roles determined for them by Rajmundus Olajus’ so-called meritocratic tests.[6] One of Alfarus’ defining characteristics was his childlike faith in the veracity of these tests, which in reality were flawed and outdated at their best and deliberately-rigged utter nonsense at their worst. Nonetheless, Alfarus would turn even on his oldest supporters if they dared criticise a single word of Olajus ‘perfect’ system, and even his wife – Madame Alfara as she is often, but inaccurately, known – was unable to reason with him on it.

Frustration with the obvious problems with the tests was likely one of the major factors behind the formation of the original secret societies which became the Black Guards. Young boys and girls assigned to particular vocations by the tests, vocations for which they were sure they were unsuited, would complain together in secret and then begin to plot subversion. None dared make a move while Alfarus lived, however. Though not prone to personality cults and not deliberately making himself a public figure, Alfarus remained a looming shadow over every Amigo or Amiga in this period. Remember that for the young people, they could not remember any time before he held absolute power. Some feared him for the rational reason that he enjoyed the loyalty of the armed Celatores who could suppress any revolt, but many more had begun to see him as something more akin to the ‘evil eye’, a supernatural presence that was always watching. It was this association that would lead to the Kaekokulus or Blindeye symbolism later on, but again, I’m getting ahead of myself.

Nonetheless, as time went on various groups of proto-Black Guards came into contact with each other and gradually became a more open movement. In so doing, they learned that there were a variety of other factors behind the resentment of different groups, beyond frustration with the flawed testing process. The two main strands of opinion in the Black Guards were largely defined by race or national background, much as any good Sanchezista might be horrified at the thought. (Audience laughter)

Firstly, there was the group that was increasingly disenchanted by how much they knew the Combine had moved away from Sanchez’s initial goals and values. One might wonder how they knew that, given how tightly controlled the discourse in the Combine was, but you must remember that Alfarus was an advocate of Doblizi Pensarum, or Dual Thought. Essentially, this meant that children were taught how the Combine should be, such as the idea that there should be no armed Celatores and that the Zonal Rejes should rotate between Zones, while also acknowledging the reality that this was not happening – attributed to ‘temporary measures while some bandit regimes remain un-suppressed’. In other words, so long as nations existed, the Combine might have ambitions to build true Societism, but would remain a military dictatorship under Alfarus’ thumb. This first faction of Black Guards consisted mostly of conceptual Meridians or ‘Firstslain’, especially Platineans, who were becoming impatient with this and began to believe that Alfarus was deliberately holding the progress of Societism back for his own selfish reasons.

The second major faction of Black Guards was dominated by non-Meridian Societist Amigos and Amigas. There were two main groups of these in turn – Nusantarans and Africans. The precise aims of the groups different somewhat, but both agreed that Alfaran Societism was flawed because it did not truly place different races and cultures on the same level. Under Alfarus, Javanese gamelans were destroyed while the Platinean guitar remained. These people were still doctrinaire Societists, you must remember. Mostly, they did not so much object to their own ancestral cultures and languages being annihilated as complain that the same attitude was not being fairly applied to residual Meridian culture. (Audience murmurs) The African group mostly had similar views to the Nusantaran group, but there was the additional complication that Karlus Barkalus still effectively ruled the Societists in Africa. They were certainly not as independent from Alfarus as the Grey Societists in Danubia and, increasingly, the Eternal State, but Barkalus’ longtime presence as Prokapud meant that the Africans were familiar with the idea of an alternative to Alfarus’ absolute power. There was no similar figure among the Nusantarans, who remained fearful of reprisals from the Celator garrisons in their islands. Regardless, this strand of opinion among the Black Guards was the beginning of what became known as the Konkursum ad Kultura or KaK, an accusation that the Combine was treated as nothing more than the UPSA and Hermandad with a black coat of paint, and continued to discriminate against non-Meridian cultures. The KaK would become emblematic of the Silent Revolution, to the point that the two are almost considered synonymous.

Under Alfarus, deliberate mixing between Societist Zones was limited, haphazard and erratic. The extreme ideas of the Garderista faction from the early Revolution had been limited, in a typically Alfaran pragmatic move, to use as a threat. Rather than all children being taken from their parents and raised in randomised communal crèches, removing a child was used as a punishment to keep dissidents in line. Early on, crèches on the Garderista model were sometimes tried for these children (itself leading to many, rather horrifying, stories) but, more often, they were adopted by families elsewhere. In practice, due to the rebellious Nusantara and Africa, this mostly consisted of children from those regions being raised by Meridian parents. Much less often, the reverse was also true. After the reconquest of Carolina in 1926, Carolinian children – white, black and red alike – were often sent to Africa or the Nusantara to be raised, which may represent a belated recognition that the process was seen as one-sided and unfair.

Besides this movement of children, individual families were also sometimes encouraged to move to different parts of the Combine. Again, this was not a well-organised system but usually a series of abortive initiatives by various ambitious administrators. Regardless, these two factors combined helped ensure that the two factions among the Black Guards encountered one another and were aware of each others’ grievances. The contradictions might have averted cooperation, but both were impelled into cooperation when the disastrous ‘Oil Standard’ economic policy of Josephus Kalvus resulted in financial ruin for many ordinary Societist Amigos and Amigas. This stirred up public anger against Alfarus among many who formerly had remained loyal, and set the stage for what would become the Silent Revolution.

The first truly open Black Guards emerged a few months before the end of Alfarus’ life, though by this point (in 1936) he had suffered a stroke and the regime was effectively already being run by his wife. These Black Guards were careful not to do anything that might make them a target for the Celatores. They wore black shirts with Threefold Eye pins, black berets with the same, and black armbands with the same Threefold Eye. It would be hard for the regime to condemn an Amigo for wearing the symbols of Societism, even if the large number of them suddenly appearing in a regimented way, as though this was a uniform, might make the leadership nervous. It is easy to see where the pejorative nickname came from.

With the final passing of Alfarus, probably from a heart attack, in October 1936, the regime was in a quandary. Alfarus had held absolute power for so long, and eliminated all rivals, that any notion of succession planning had always seemed tantamount to treason. Madame Alfara, or Maria Vaska as we should properly call her, became de facto leader of the Combine simply because she had been acting in her husband’s name. Emilius Gonzalus, a senior Celator and hero of the War of 1926 (Audience reaction) from their perspective, that is…Gonzalus was named Kapud and successor to Alfarus. The third member of the ruling triumvirate was Markus Lupus, the last surviving link back to Pablo Sanchez. Actually, Lupus – then called MaKe Lopez – had only met Sanchez briefly when he had been a young man, and had worked more with Raúl Caraíbas, but the line between the two had been increasingly blurred for years. Regardless, Lupus was now eighty-seven years old and had little capacity to act in a leadership position, but he was held up as a symbol of legitimacy by Vaska and Gonzalus.