King George V

Part Two, Chapter Fifteen: Exits and Entrances

Part Two, Chapter Fifteen: Exits and Entrances

The Christmas of 1839 could only ever be described as bittersweet for the Royal Family. As they gathered at Windsor Castle to celebrate the festive season, George V noted in his diary that “there seemed far fewer of us than ever before”. The Dowager Duchess of Clarence had hoped to go to Windsor but just before setting off from Clarence House, she developed a chill. She was advised by her physician that if she still intended to accompany the Cambridges (and the Princess Royal) to Germany in January, she must stay in London to recover. At Frogmore, Princess Augusta was deemed too unwell to make the short journey to the castle. She had been in poor health for some time but now, she appeared to be entering the final phase of her illness. Nursed by her sister Princess Sophia, Augusta believed she would not see out the year (a family trait of pessimism where sickness was concerned) and had even begun ordering her servants to tie white ribbons around objects she had reserved to be given to the Royal Collection upon her eventual demise.

A new face at Windsor that year meant that a familiar one elected not to attend. In a gesture of goodwill, the King and Queen had asked the Duke and Duchess of Sussex to join them for the Christmas celebrations. They were to stay at Royal Lodge and not at the castle itself, and the invitation was only extended for luncheon on the 25th and for a ball to be held in the evening of Boxing Day; the Sussexes were not to join the Royal Family for the traditional Christmas Eve gift exchange or supper. Still, this proved too much for Princess Mary who opted to spend Christmas at Frogmore with her two sisters, only seeing the King and Queen in person for the Christmas morning service at St George’s Chapel, Windsor. Mary was still incensed that the King had sanctioned the Sussex marriage; his decision to offer formal recognition to the Duke’s bride meant that she was now entitled to the style of Royal Highness.

The gathering on Christmas Eve was therefore smaller than before with only the King and Queen, the Princess Royal, Princess Charlotte Louise and the Cambridges present. The Queen was to begin her confinement in a matter of weeks, her second child due in just two months, and though Dr Allison had asked her to bring her laying in forward by a month, the Queen refused; she would not miss a single moment with Missy ahead of her departure from England on January the 10th the following year. Yet amidst the sadness of their parting on the horizon, the King and Queen did their best to have a jolly time. The King gifted his wife a pair of 17th century Delftware tulip vases for her collection; unfortunately, everybody had heard of the Queen’s fondness for the ceramics, and she was inundated with jars, vases, plates, cups, saucers and even a bowl which the sender had clearly not realised was actually a shaving dish. Shortly before supper was served on Christmas Eve, Queen Louise nodded to Charlie Phipps who opened the doors to the Great Hall and amid excited yaps and coos of approval, two King Charles Cavalier Spaniel puppies came bounding in towards the family.

One of these puppies was a Blenheim boy, the white of his muzzle broken up with a ‘Blenheim Kiss’, a blot of chestnut fur in the middle of the forehead. He was a gift for the King, the Queen becoming increasingly concerned that her husband’s childhood canine friend Jack was nearing the end of his days. George was thrilled and named his new companion Harry. Harry quickly asserted himself as top dog and took a shine to the Queen’s spaniel, Diamond. Harry and Diamond would give the Royal Family more puppies, the spaniels becoming the favoured royal pet for decades. The second puppy was a gift for the Princess Royal and was a black and tan female who was given the name Holly. Holly would go with Missy to Bautzen, though she made quite the first impression on Lady Dorothy Wentworth when she became too excited and wet on Dolly’s skirt. The Cambridges had no idea that the Queen was to give new pets as presents and added to the chaos when they presented the Queen with an African grey parrot named Sybil.

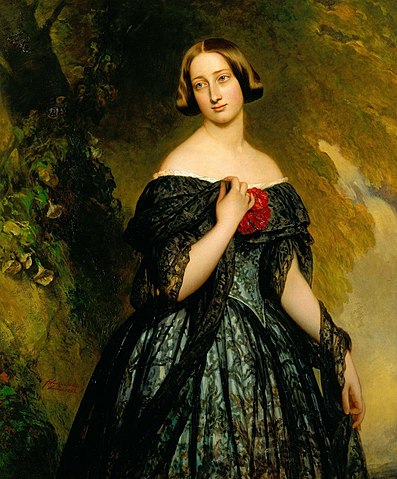

Another gift which raised eyebrows was the arrival of a box from St Petersburg and which was laid among the other presents in the Great Hall. The box came from the House of Bolin, the most important jeweller in Russia before that most coveted spot was challenged by Fabergé in the late 19th century. Bolin had been commissioned by the Tsarevich to create something special for his intended; the jeweller did not fail his client. The Tsarevich’s gift was a devant de corsage, a large piece of jewellery intended to be worn on the centre panel of the bodice of a dress. But Bolin had gone beyond producing yet another fashionable stomacher. This piece boasted a large emerald as the focal point and by turning three small clasps, the diamond pendants could be removed leaving the emerald surrounded by brilliants as a stand-alone piece to be worn as a brooch – with or without a diamond drop at it’s base. When the King saw the gift, he could no longer placate himself that the Russian match was still not a serious prospect. Sasha’s intentions were clear for all to see. [1]

The Bolin Stomacher gifted to Princess Charlotte Louise by the Tsarevich. The piece no longer exists but this is the original design found in Bolin's archives.

But far away from the extravagant presents and lavish suppers at Windsor, Christmas 1839 was a thoroughly miserable time for the vast majority of the King’s subjects. The food crisis had reached breaking point, and many have suggested that had it not been for the announcement of a general election, the riots which occurred across England with alarming regularity may have been much larger and far more impactful. Others have suggested that the reason such riots did not gather more interest was nothing at all to do with the election (the working classes cared more for bread than the ballot) but because most were simply too hungry to make the long journeys to cities and towns to join the uprisings. At Crowhurst, the Prime Minister gave the green light to introducing the so-called Russell mechanism as soon as parliament sat again the new year. This would tie the price of bread to the supply and make wheat and other grains more affordable. But it was only a short-term solution and not one that brought much comfort in the days of the Winter of Discontent.

Lord John Russell was pleased to see his proposal taken up (not that Edward Stanley had left Lord Cottenham much choice) but he felt a definite sense of frustration too. He could not see any way in which the Whigs might convince the electorate to stay the course and he seriously worried that many of his colleagues would find themselves ousted from the Commons. The Russell Group was mostly comprised of backbenchers in marginal seats. If their seats were taken by the Tories (or worse, the Unionists), then he would find his cabal of supporters stuck outside the walls of the Palace of the Westminster and whatever happened in the general election, Russell might once again find the top job eluded him. Sir James Graham had no such anxieties. In his mind, the Whigs were a busted flush. They would be out of office by the Spring and the Tories returned to government. To that end, he gave a party at his London townhouse to celebrate the New Year where the Tory grandees toasted the future ahead with champagne – and jostled for Cabinet posts between glasses.

One politician who shared Graham’s confidence was not a prospective Cabinet minister but an incumbent one. Lord Melbury had become something a royal favourite and the King had taken him into his confidence as a close friend. In later years Melbury would say that whilst he still felt a knot in his stomach when he recalled his earlier clash with George V, it had “broken the ice and allowed us to speak our minds, to put aside position and rank, and to enjoy a friendship which I consider to have been sincerely cherished by both parties”. Melbury was invited to attend the ball given on Boxing Day at Windsor and whilst there, he privately warned the King that he may soon be facing a change of government. In the Foreign Secretary’s view, the Tories were likely to win a decent majority and the Whigs would remain in the political wilderness for quite some time. George noted this in his journal but attributed no opinion of his own to Melbury’s predictions.

Indeed, George’s diary entries during the Winter of Discontent do not focus so much on politics but rather on the departure of the Princess Royal and the impending confinement of his wife. He was certain her second child would be a boy and jotted down that he had already chosen the name of the new Prince of Wales. He was to be called William Edward George Frederick, William in honour of the late Duke of Clarence, Edward in honour of the King’s late brother, George for the King and Frederick for the King’s late father. But there are two other names which appear in the pages of the King’s journal at this time which are of great interest to royal historians. Prince Alexander of Prussia had been a close friend to the King for years and from 1839 onwards, Alexander became a regular at court once more. He was accompanied by his mistress, Rosalind Wiedl. Whilst many in London society frowned on this relationship, the Queen knew that the King could only see the good in Alexander and so she extended a welcome to Wiedl too, the two women becoming close friends themselves.

Rosalinde Wiedl.

George wished the Prince to remain in England for a while, presumably to help cheer him when the Princess Royal had left and when his time with his wife was to be heavily restricted according to the customs surrounding childbirth in this period. But perhaps George also saw that Alexander was spiralling somewhat. He drank to excess and even though Rosalinde Wiedl was his primary companion, there were other women too – usually found in the brothels of whichever grand city Alexander found himself in. The King offered the Prince and his friend the use of Fort Belvedere on the Windsor estate for a few months before it’s redecoration. At New Year, George gifted his sister Marlborough House with the lease placed in her hands for the duration of her lifetime, not the King’s. He had intended to gift her the Fort too but he had opted instead to refurbish the property and wait and see what happened with Charlotte Louise’s marriage prospects.

It was after visiting Prince Alexander at the Fort that for the first time beyond a mention of her name, the King gives his impression of Rosalinde Wiedl. The thirty-year-old widow was well liked by the Cambridges and distinguished herself by using her existing friendship with the Sussexes to make the new Duchess feel comfortable in a room full of gossips who were clearly fascinated that she had finally been welcomed to court as a member of the family [2]. “Frau W. is a lady with a most excellent sense of humour and one can quite see what Alexander finds so appealing in her character. She made a wonderful addition to the party and Sunny told me that she thought it a great shame that Fritz and Lulu consider her a bad influence for there is little evidence that any of Xander’s poor behaviour is encouraged by Rosa. I found the opposite to be true for it was Rosa who stopped X from taking more wine at luncheon when he was already quite intoxicated. Sunny was most put out as he became a crashing bore but afterwards agreed with me that Rosa had rescued the gathering by being so very witty”.

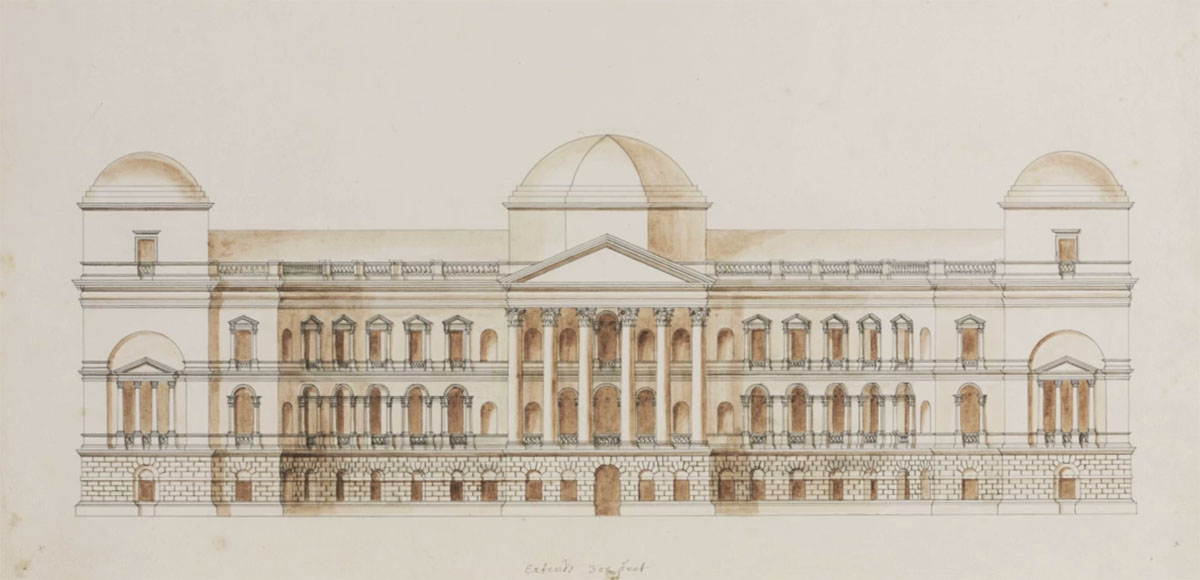

Another guest present in the New Year’s celebrations at Windsor was Decimus Burton. Burton was something of a workaholic and instead of arriving simply to have a good time, he brought with him his revised plans for the Regent’s Park development. Building on the work he had already contributed to John Nash’s original designs; he had produced something that delighted the King and mid-ball, George took his Uncles Cambridge and Sussex into his study with Burton to show them the plans for the first time. Both agreed that the end result would be very impressive indeed if the works could be afforded. But the King was not to be dissuaded. He was boosted by Burton’s second gift that evening; the news that Hanover House at Broadwindsor would be completed by the autumn at the very latest; “Then that is where we shall spend next Christmas”, the King cried happily, “And Uncle Cambridge, I shall have no excuses – you shall be back with us at Hanover House next year – those old ruins at Herrenhausen can’t have you all the time, what?”

The King had finally made his peace with the idea that this Uncle would be leaving England. He had also accepted that his daughter would go with him. But on the 10th of January 1840, the reality of these separations could no longer be spoken of as future plans. The Cambridges, accompanied by the Princess Royal in the charge of Lady Dorothy Wentworth, left Windsor Castle for London. There they would spend a night at Cambridge House and the following day, joined by the Dowager Duchess of Clarence, they would travel to Harwich to board the Royal Yacht for their journey to Germany. The King and Queen’s stoic approach to bidding their daughter farewell could not fail to impress. They did not shed a tear, insisting that any displays of sorrow might upset Missy and distress her. So it was that they watched the parade of carriages leave Windsor and rattle through the George IV Gate, carrying their daughter away for her new life at Bautzen. The moment the coaches disappeared from sight, the Queen fell to her knees and let out a painful scream. The King rushed to her aid, now openly weeping himself. Charlie Phipps and the Duchess of Sutherland assisted George in getting Louise safely to her bed. Sutherland said of the incident; “I had never before seen the Queen so desperately wounded, so utterly tormented. Dr Allison came and prescribed a sleeping draught, after which Her Majesty slept soundly”.

For the next week, a pall of sadness drew itself over Windsor. The King waited anxiously for news that his daughter had arrived on the continent safely, whilst his wife entered her confinement, ate alone in her room and slept as much as possible to hide from the agonizing reality of what had just occurred. When he could bear it no longer, the King made his way on foot to Fort Belvedere where he tried to enjoy the company of Prince Alexander. But Alexander had become churlish and unpleasant company. When he was not drunk, he was suffering from terrible hangovers that left him riddled with anxiety and self-loathing. He was hardly the company George needed at such a difficult time. When George made his way to the Fort for dinner one evening, Frau Wiedl gave her apologies. Alexander had passed out cold after yet another binge. The King made to leave but then hesitated; “I wonder if I might impose and take supper with you then Frau Wiedl?”, he said sadly, “I simply cannot bear to go back to my study tonight”. The pair ate together, Frau Wiedl trying her best to raise the King’s spirits by playing some of his favourite tunes on the piano when their meal was over. George found himself smiling. And so it was that this tête-á- tête was repeated the next evening. And the next.

There was a brief moment of hope on January the 13th when word came from Germany. Sadly, it was not from the Duke of Cambridge. Rather it was a letter from Bad Homburg; the King’s aunt Elizabeth had died on the same day the Cambridges had left England. As Princess Mary had predicted, the Duke was too late to catch Elizabeth’s final hours and by the time he reached Hanover, the Hesse-Homburgs had held a funeral service for his sister and interred her coffin beside that of her husband Frederick VI at the Mausoleum of the Landgraves. George had never really known his aunt but perhaps inspired by the sober mood of the day, he insisted that 14 days of court mourning be observed and there was a memorial service for the Princess at St George’s Chapel, Windsor which was held in the evening of the 15th of January. It was attended by the Princesses Mary and Sophia. The Sussexes had returned to London and Princess Augusta was too ill to leave Frogmore. The Queen was represented by the Duchess of Sutherland.

All seemed to be doom and gloom and not at all the bright start to the new decade the King had hoped for. Then, on Friday the 31st of January, the King invited some of his closest friends to Windsor for a hunting weekend. The Duchess of Sutherland thought this quite disrespectful given the circumstances, but Dr Allison chided her; “There is nothing wrong with Her Majesty that the first sight of her baby will not cure, and it’ll do the King some good to be out in the field”. Those in attendance included Prince Alexander (in a rare few days of sobriety), Lord Melbury and Henry Glazebrook, Melbury’s financial advisor. The King wanted an outside opinion on Burton’s plans for the Regent’s Park development and Glazebrook was invited to Windsor solely for the purpose of casting an eye over the designs and offering a frank assessment of the economics of the project. It was whilst George was showing Melbury and Glazebrook the Burton plans in his study that a beaming Charlie Phipps arrived with an urgent message from The Hague. Princess Victoria had given birth.

Princess Victoria Paulina of the Netherlands was born on the 24th of January 1840, the first child to be born to Prince William and his wife Victoria. The little Princess’ arrival raised eyebrows both with regard to her name and to her sex. The Prince wished to name her Wilhelmina in honour of his ailing grandfather King William I but his wife put her foot down. Her daughter would be named after her mother and grandmother. Fortunately, the Prince was not in one of his more capricious moods and gave in, but he insisted that the second name of his new-born daughter honour her Dutch relations. Still somewhat stubborn, Victoria discounted Wilhelmina entirely and (avoiding any real connections to the House of Orange) selected Paulina in honour of the baby’s paternal great-grandfather, Emperor Paul I of Russia. Many expected William to be angry that his first born child was not a son. Yet he was delighted with his daughter and refused to hear mention of the fact that his wife had failed to produce a fine prince instead.

The Henry Bone portrait of the two Victorias given to Princess Victoria of the Netherlands (née Kent) in 1840 by George V.

King George and Queen Louise were invited to serve as godparents to Victoria Paulina (known as Linna within the family) with Prince Alexander of the Netherlands standing proxy for the King and Victoria’s sister-in-law Princess Sophie standing proxy for the Queen. King George responded to the message with an unusual gift; he ordered Phipps to find a portrait of Princess Victoria with her mother and dispatch it to The Hague. Victoria had grown up with every picture of her mother, the late Duchess of Kent, hidden from her and when she received the Henry Bone portrait which showed the Duchess and her infant daughter together, she wept tears of joy. It would forever find a home in Victoria’s bedroom, and it is said that when she died in 1901, she looked up to the portrait and said softly, “Dearest Mama” before she breathed her last.

In the first week of February 1840, parliament was prorogued ahead of the March general election. George was in a much happier mood, buoyed by the good news from the Netherlands and anxiously awaiting the arrival of his son. Dr Allison predicted that it would not be too long before the little one made his appearance and the King, eager for his child to do so, did not stray too far from the castle so that he might be called the moment Queen Louise started her labour. For the most part, he spent his time studying the Burton plans (which Glazebrook believed were financially sound, though he warned that the end result might not return a profit for some time and would only ‘wipe it’s face’ for the first ten years). Supper was taken in his study alone, except for two occasions when he was joined at the castle by Prince Alexander and Frau Wiedl.

Suddenly, these quiet hours were disrupted when Dr Allison informed His Majesty that he should summon the various VIPs who had to be on hand to witness the royal birth; these included the Archbishop of Canterbury (or York, whichever was easiest to track down), the Home Secretary, the Lord President of the Council, the Lord Chancellor and other establishment figures who came to regard such a formality as a good excuse to enjoy royal hospitality. They could expect three or four days of the very best food from the royal kitchens (not to mention the same quality in wines from the royal cellars) and often those who took part in this ancient ritual were disappointed when the baby arrived, and their weekend of gluttony was ended.

For those who assembled to witness this royal birth, their revels were to be cut even shorter. The Queen began her labour around 8.30pm on the 16th of February. By 2am, the Queen’s bedroom in the private apartments was filled with the screams of a very healthy baby girl. The King was waiting anxiously for news. In the back of his mind, he could not shrug the nagging worry that there might be a complication as there had been during Missy’s birth. But his worries were quickly eased by Dr Allison; the Queen and her baby (weighing 8lbs 3oz) were in the very best of health. The King stepped into his wife’s bedroom, kissing Louise tenderly on the forehead and taking his daughter in his arms from the Duchess of Sutherland. The Queen looked nervous; “I had so hoped I would give you a son this time Georgie”, she said softly. The King smiled at his wife. He was disappointed not to be cradling a little Duke of Cornwall in his arms but one look at his daughter’s face and any sentiments of that nature dissipated; “She is a fine little girl. And as beautiful as her mother”.

Content though the King was, he had been so certain that he would have a son this time around that he hadn’t considered names for a daughter. But the Queen had. George had taken the lead when Missy was born and so this time, he bowed to his wife’s preferences. Not that the Queen had chosen anything particularly unexpected, indeed, she looked to the King’s own family and not her own. The little girl was given the names Victoria Mary Charlotte Elizabeth; Victoria in honour of Princess Victoria of the Netherlands, Mary in honour of the Dowager Duchess of Gloucester and Edinburgh, Charlotte in honour of the King’s sister and Elizabeth as a tribute to the recently deceased Dowager Landgravine of Hesse-Homburg. Princess Victoria would be known as Toria. Her godparents were Princess Victoria of the Netherlands, Princess Mary, Dowager Duchess of Gloucester and Edinburgh and Princess Augusta of Cambridge, the Duke of Sussex (a typically kind-hearted gesture from the conciliatory Queen), the Queen’s brother Hereditary Grand Duke Frederick William of Mecklenburg-Strelitz and Prince Alexander of Prussia. The King approved, though he wondered how on earth he would get his aunt Mary to the christening in the presence of his Uncle Sussex.

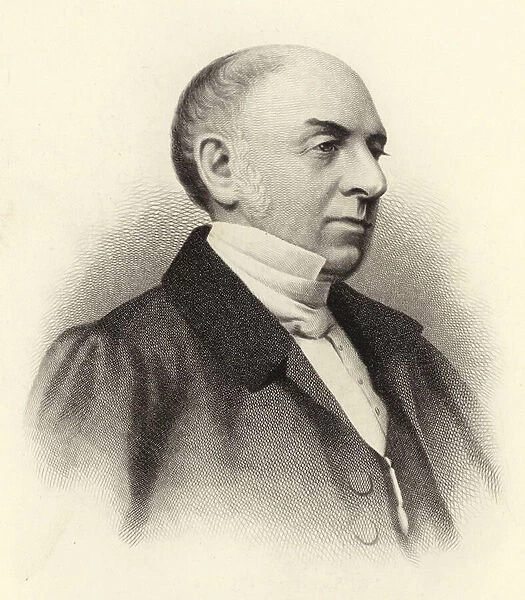

Prince Alexander of Prussia.

The news of the royal birth was received with muted happiness in England. Whilst most were to be considered “the new royalists” described by Charles Greville, it was difficult to feel too much joy when the vast majority were facing so many problems of their own. With this in mind, the King ordered that special gift boxes ranging from £5 - £15 be sent out to all collegiate churches in the country to serve as poor relief. This gesture was a kind and well-intentioned one but sadly, unscrupulous clergy opted not to use the King’s gift immediately and simply added it to the overall fund for the year (with the result that many gift boxes went straight into the pocket of the parish councillors). Nonetheless, the usual messages of congratulation poured in and the King and Queen were relieved when Dr Allison confirmed that little Toria was healthy in every way with no trace of any difficulties. For a brief moment, the Queen especially had feared that Missy’s deafness may be hereditary and might show itself again in their second child.

As soon as she could leave her bed, the Queen asked the Duchess of Sutherland to help her cast Princess Victoria’s hand in plaster. The sleeping princess had her right hand dipped into a bowl of gypsum (ironically the Princess would grow up to be left-handed) and the result was placed on the Queen’s dresser in her bedroom. A second cast was taken to be dispatched to Missy in Bautzen. It was accompanied by a note from Queen Louise; “For my darling elder sister whom I shall love and cherish always”. Louise could allow herself to be happy despite wishing the Princess Royal was with her parents to see the new arrival. Yet she could also allow a moment of relief that she had “done her duty”. Whilst she may not have provided a son and heir, she had produced two daughters. The Line of Succession to the British throne was secure for another generation.

The King too refused to be glum. He celebrated his daughter’s birth with a glass of champagne, a rare break in his abstinence from alcohol. As the Queen slept, the King sat in his study with Prince Alexander and Frau Wiedl, the latter congratulating the King on the latest addition to his family.

“I’d have liked a boy”, the King replied smiling, “But it appears I am destined to be surrounded by women. And very beautiful ones at that”.

He drained his glass and bid his friends goodnight, sleeping soundly in his bed for the first time since Missy had left for Germany.

[1] Bolin was the favourite court jeweller in St Petersburg, and he specialised in multi-purpose jewels which could be worn two or three ways. I suppose when you’re buying gems as big as plover’s eggs, you want to be able to show them off in many varieties!

[2] Cecilia was already Duchess of Inverness but here she is the “new” Duchess of Sussex in addition to her previous title.

[3] See Appendix I in Threadmarks.

Note

The next instalment is written and ready to go and it's that one which contains our set-up for the Palace of Westminster poll. Apologies to those who expected it in this one as promised (a calendar mix up on my part) but you won't have long to wait!