King George V

Part One, Chapter Five: "Farewell Mother"

Part One, Chapter Five: "Farewell Mother"

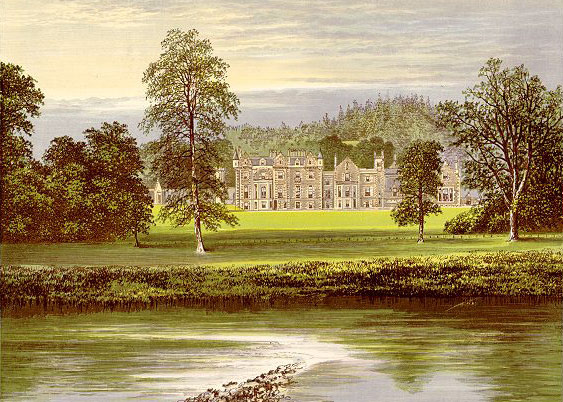

In the aftermath of Prince Edward’s death, the Clarences arranged for Queen Louise to be brought from Abbotsford to Windsor for the funeral. The Duke wrote a letter to the Dowager Queen informing her of the arrangements he had made whilst the Duchess ensured that Royal Lodge was aired and fresh food and bedclothes were dispatched from Windsor Castle to provide Louise with everything she might need. But the Queen had no intention of returning to Windsor for her son’s funeral. She was therefore absent as members of the British Royal Family gathered at St George’s Chapel on the 14th of January 1829 to see Prince Edward laid to rest beside his father, King George IV, in the Royal Vault. Also absent were the royal children. Baron Stockmar felt the event would “prolong melancholy” and so instead, ordered the King’s tutor, George Cottingham, to take the children to Eton for the day where they were given a tour of the college. The young King was to enrol as a boarder there in a year’s time but his first impressions were not good. He found the college “unfriendly and cold” and he also realised that as a boarder, he would be removed from Windsor and the company of his sister. Recent events had made him more dependent on her friendship than ever.

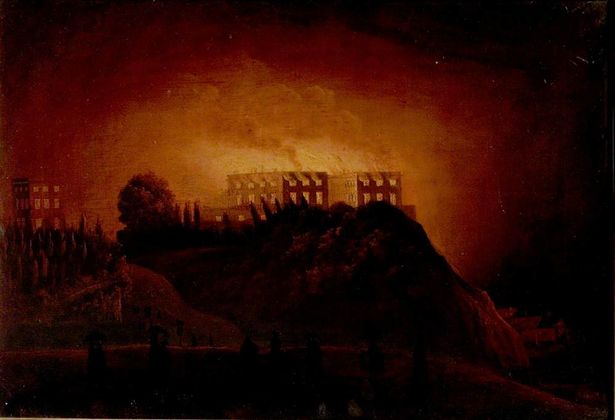

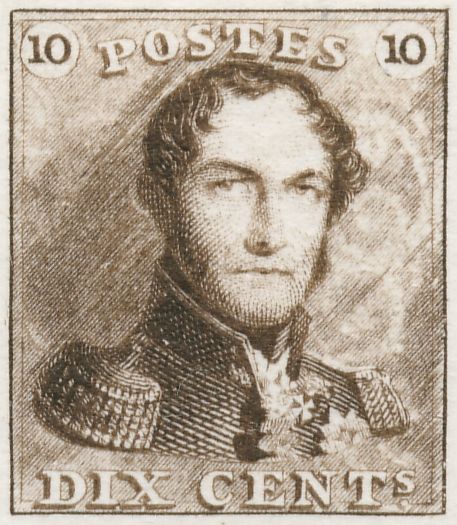

Since the death of her husband, the Dowager Queen had retreated to Abbotsford, the home of Sir Walter Scott which the late King had leased as a holiday home for the period of ten years. But with George IV's death, the lease had come to an early close and the entire sum had to be paid to Scott’s creditors from George IV’s private fortune. Queen Louise had been given the opportunity to extend the lease and had asked the Duke of Clarence to arrange this out of King George V’s inheritance as a trustee but the Duke refused to do so. This was not, as Queen Louise insisted, a petty act designed to upset her but rather an attempt by the Duke to force Louise to return to her children at Windsor. Louise was more concerned with maintaining her lifestyle at Abbotsford however, a place she had very much made her own and where she was able to hold court among a group of sycophants who overlooked her faults and foibles.

Abbotsford House.

These included Sir Walter Scott, the Duke and Duchess of Gordon and her former lady-in-waiting, Baroness Pallenberg. Pallenberg had accompanied Louise to England in 1819 but had found herself ceremonially dismissed when the Queen refused to accept the appointment of other ladies in waiting by the Prime Minister, Lord Liverpool. Louise had come to accept the situation, even becoming close to the Liverpool appointments she had once gone to such lengths to reject. But in 1827, the Marchioness of Westmeath had been divorced and therefore had left the Queen’s employ. With the change in government, the last of the Liverpool intake, Lady Melville, was also to be replaced and, believing that as she was not resident in London it did not matter who served in her household, Louise invited Baroness Pallenberg to join her in Scotland.

The Duke of Wellington cared little for domestic squabbles in the Royal Household. He advised the Queen that he was more than content for Pallenberg to serve in her household as long as she accepted his appointments; Susannah, Countess of Harrowby (wife of the Lord Privy Seal) and Sarah, Baroness Lyndhurst (wife of the Lord Chancellor). When Lady Harrowby arrived at Abbotsford, she was appalled at the situation. She wrote scornfully of the Gordons who “puff up the Queen in her hauteur and encourage her selfish nature. They shower her with praise for the most mundane things and she has come to rely on the Duchess who has a religious mania that is quite exhausting”.

The Gordons liked to portray themselves as the very model of aristocracy, spending most of their time on their Scottish estates in Aberdeenshire which included Huntly Castle on the crossing of the Rivers Deveron and Bogie, and Glen Tanar, the third largest area of the Caledonian Forest through which the Water of Tanar flows into the River Dee. They had an impressive townhouse in London too where the Duke stayed when his presence was required in parliament but by 1829, these appearances became less regular as he established a reputation as something of an extreme reactionary. He opposed Catholic emancipation and deeply disliked the Duke of Wellington whom he regarded as a “naïve reformer and traitor to the protestant faith”. Whilst Lord Eldon had indulged the Duke of Gordon, Wellington did not and he found himself with few allies in the Lords, even among the Ultra Tories. As a result, he spent more and more time in Scotland in his post as Lord Lieutenant of Aberdeenshire and Governor of Edinburgh Castle.

These lofty appointments were not reflected in the Duke’s income. Overwhelmed with debts and consistently forced to sell off parcels of his inheritance to keep himself from sinking into bankruptcy, the Gordons were playing a constant game of deception. To the untrained eye, they lived a life of great luxury and had land and treasures to spare. Yet everybody in society knew that the Gordons had nothing and that their marriage had soured after the Duchess had failed to provide a much sought-after male heir. In the late 1820s, she became horrified by the revelations of what life was really like in London’s high society and as a result, she sank into a religious fervour that saw her make a complete renunciation of her worldly goods. Fortunately for the Duke, this meant the great wealth she inherited which he wasted no time in losing at the card table. The Gordons became a permanent fixture at Abbotsford, the Duke boasting of his friendship with the King’s mother to any who would listen, the Duchess giving long and dull sermons to Queen Louise who seemed oddly comforted and enthused by them.

General George Duncan Gordon, 5th Duke of Gordon.

It was the Gordons who provided the catalyst for Queen Louise’s dramatic departure from England that summer. Whilst visiting Huntly Lodge, the run-down castle in Strathbogie which the Gordons called home, Queen Louise was taken for a tour of the Glen Tanar estate. Sensing a financial opportunity, the Duke dropped not so subtle hints that he would have to part with more of the estate in the future but he had hopes that friends would buy the land so at least the Gordons could still visit occasionally. Queen Louise was not without money. She had a generous annuity and a healthy personal inheritance left to her by George IV. Whilst she had intended to give in and simply purchase Abbotsford from the creditors when they were forced to sell the property, she now saw a solution to her problem. Glen Tanar would make the perfect site for a new house that she could design and furnish to her own tastes. She could remain in Scotland for as long as she wanted without giving into the Duke of Clarence, whom she believed had only refused to extend the lease on Abbotsford to force her to return to Windsor. With money before his eyes, the Duke of Gordon proposed that Louise could choose the land she wanted but that there would be no further personal inconvenience because the exchange would be dealt with entirely by her solicitors.

The house itself would be built on the banks of the Allt na Cloch River, with the back of the property shielded by woodland. This would give ample access to the grouse moor and stalking at Black Craig. The new property would enjoy almost total seclusion with the Glen Tanar estate owned by the Gordons some 30 miles away. At the Duchess of Gordon’s suggestion, architect John Smith was commissioned to produce designs for the new house which was to be given the name Queen’s Taigh (Queen’s House). Smith had previously worked on Cluny Castle, Castle Fraser and Craigievar and came highly recommended. Queen’s Taigh was designed to incorporate eight-bedroom suites, a ballroom, dining room, picture gallery and music room along with two drawing rooms, two morning rooms and a vast library. The house was to be encased in pink Peterhead granite with grey slate rooves.

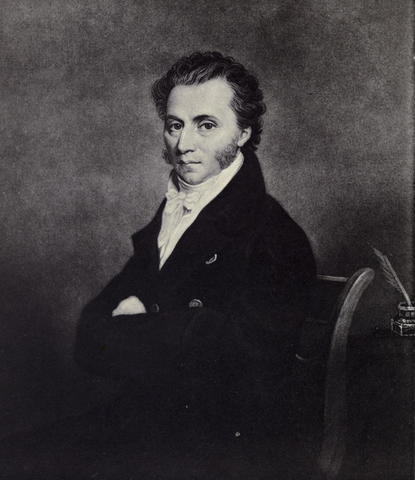

These plans went ahead in Scotland with no word sent to Windsor. Indeed, the Duke of Clarence only found out that his sister-in-law planned to buy Glen Tanar land and had already commissioned John Smith when the Duke of Wellington brought him the news at one of their weekly audiences. Clarence was furious, not because he begrudged his sister-in-law a residence in Scotland, but because she had made absolutely no attempt to contact her children in months. The Duke of Wellington was uneasy for other more pressing reasons. Whilst Buckingham Palace was now in use as a royal residence, the architect John Nash had not yet completed the project and his designs seemed to be getting more fanciful by the day. Just when the Office of Public Works deemed the work to be nearing completion, Nash would submit another set of designs that included all kinds of expensive novelties. One such idea was to run a canal along the length of what is now Pall Mall and to connect it to the Serpentine in Hyde Park. The final straw came when the Office of Public Works were asked to raise more money to fund the construction of a triumphal arch to serve as a state entrance to the cour d’honneur of the Palace. Nash was removed as the architect and Edward Blore appointed to finish the works once and for all. [1]

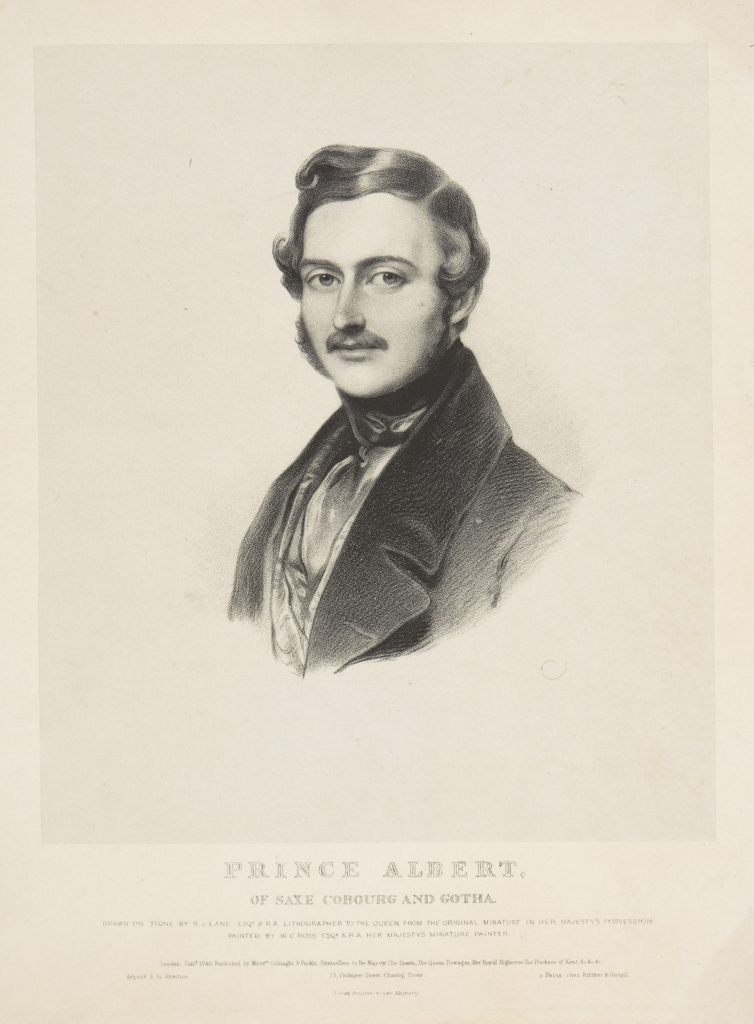

Edward Blore, architect.

But Blore would still need additional funds to complete the Palace to his new designs, even though they were much plainer. The Duke of Wellington accepted this as necessity and indeed, he felt that even though there was likely to be opposition in parliament to a Civil List increase to fund the works, the change of architect and a definitive completion date would get the bill over the line with ease. But Wellington feared a repeat of the Kew Scandal [2] if parliament was made aware of the Dowager Queen’s plans for a brand-new residence in Scotland. To be fair to Queen Louise, she could easily afford to fund Queen’s Taigh from her own means and there was no suggestion at all that public funds would be used. But the Queen had not been seen in public since her husband’s death and the public mood was against her. Many could not forgive her for not returning to England when Prince Edward died and though the press were kind enough to report that her “enormous grief precluded Her Majesty from undertaking the long journey and thus she mourned privately at Abbotsford”, those in the know were not impressed. Blore was a great personal friend of Sir Walter Scott and convinced him to ask Louise to at least postpone her purchase of Glen Tanar by a year.

Writing to her brother-in-law the Duke of Clarence, she raged that she had “only ever sought to comply with [the Duke’s] wishes as regent and being shown little kindness in my mourning, I retreated to Scotland where I found a peace in my loneliness that I could not find at Windsor”. She continued; “My position has been stripped of me, my ladies dismissed and my home here taken away by grubby solicitors acting on your instructions. I see no reason why I should delay my plans at Glen to accommodate the petty squabbles over the cost of my son’s palace in London, a palace in which I shall clearly never reside as my late husband intended. To this end, I shall abandon my plans at Glen but I see now that you shall not be contented until I am a stranger to this country and an even greater distance is put between His Majesty and his mother”. Louise announced that she would return to Windsor briefly in the summer of 1829. She would stay at Royal Lodge and whilst there, she would gather her belongings and depart for Hanover where she would stay at Herrenhausen with her brother-in-law and sister, the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge, for the foreseeable future.

This put the Duke of Clarence in a very difficult position. He knew that whilst in Germany, Louise was likely to mix with relations and courtiers who would be only too happy to spread gossip that he had forced the Dowager Queen to leave England and that he had somehow hijacked the young King for his own greedy ambitions. But the Duke, though vain, was also a man who had become devoted to his niece and nephew and he seemed genuinely concerned that the Queen’s departure would be a horrible blow to King George and Princess Charlotte Louise. Even the unsentimental Baron Stockmar could see the situation may have a seriously negative effect on the children, especially when they had only just lost their younger brother. Clarence and Stockmar tried one last attempt, despite their personal dislike of Queen Louise, to convince her to stay in England.

Queen Louise wearing the Rumpenheim Tiara, c. 1822.

Clarence wrote to Queen Louise in Scotland. “I am grieved Majesty that you would take such a drastic step”, he said, “Whilst I appreciate your feelings, I must confess that I have only ever sought for my own part to do the duty laid down to me by my late brother and I feel that your departure from England would give many great sadness, not least His Majesty and Her Royal Highness. Therefore I ask you to reconsider and meet with me when you return to Royal Lodge and I pray we may find a solution to this unhappy state of affairs for us all”. Louise did not reply. When she arrived at Royal Lodge in June 1829, she found it much as she had left it, though the Duchess of Clarence had personally seen to it that the house was as welcoming as it could be. She left a note asking Queen Louise to inform Baron Stockmar the moment she wished to receive her children and promised that they would be ready and waiting at Windsor to greet their mother “whom they love so very much and whose absence has troubled them greatly”. Instead, Queen Louise summoned the Master of the Household, Sir Frederick Watson, and gave him a list of belongings she wished returned to her before her departure for Hanover. She had no interest whatsoever in seeing her children.

Watson took the list directly to the Duke of Clarence. Whilst for the most part Queen Louise wished personal items such as a miniature of the late King, a clock from the Queen’s Bedroom at Windsor and letters from her mother stored in the Round Tower, further down the list was a more troublesome request. She wished the Master of the Household to retrieve items of jewelry for her which were being stored in the vault at Buckingham Palace; the Rumpenheim Tiara, gifted to Queen Louise by her father on her wedding day, the Clans Tiara, a gift from the Chieftains of the Clans of Scotland presented to her during her first trip to Scotland with George IV in 1822 and the Rose Parure gifted to her by her late husband (first worn at the Dutch state banquet at St James’ Palace in 1825) made by Garrards and comprised of a tiara, necklace, earrings, two brooches and two bracelets set with diamonds and Burmese rubies. The Duke refused. According to tradition, the Queen’s jewels (along with those of her predecessors) were stored together and considered an extended part of the Crown Jewels for which Garrards, as Crown Jeweller, had full responsibility. This responsibility did not, according to the Duke of Clarence, extend to seeing the pieces leave the country. His compromise was to allow the Rumpenheim Tiara to be sent to the Queen as this had been a gift from her father. The rest of the Queen’s jewels would remain in England.

Whether Clarence was right or wrong in his assertion, this only fuelled Queen Louise’s hatred of him. When Sir Frederick Watson returned to Royal Lodge with only the Rumpenheim Tiara, she refused to take it and said, “If William wants my jewels for his wife that sorely, he may keep the lot”. In the coming years, she would appear at dinners in Hanover wearing no jewels at all and if anybody commented (usually prompted by Louise), she would tell them that all of her jewels had been seized when the King died by the Duke of Clarence and that the Duchess of Clarence was swanning around London wearing Louise’s wedding tiara “as if it were her own”. But this pettiness paled into insignificance for Clarence when Louise left Royal Lodge without seeing her children. She left no note, no gift and no explanation. For the next eight years, Louise communicated only with her son, King George, and even then, letters were sporadic. As for Princess Charlotte Louise; “My mother became a total stranger to me. She displayed no interest in my life or wellbeing and this placed such a heavy burden upon me that I confess I wept often for the maternal warmth I was so cruelly denied”. The relationship between mother and daughter was never repaired.

Though she returned to England in 1837, Queen Louise was not invited to attend either of the two ceremonies which comprised her daughter’s wedding in 1840 and she was never introduced to Charlotte Louise’s children. “I am strangely grateful that she displayed to me a poor example of motherhood”, Charlotte Louise later wrote, “For it made me determined to be the most loving mother I could be to my own dear children”. The effect of this departure on the young King was equally gruelling. When it was explained to him that his mother had left Royal Lodge without seeing him, he asked where she had gone. "To Hanover, to see your Aunt Augusta for a time", Honest Billy lied. The young King spent the afternoon painting a picture of the two ladies together. At the bottom, he wrote; "Farewell Mother, love Georgie".

Royal Pavilion, Brighton.

Whilst Baron Stockmar was content to see the back of Queen Louise (“the King has been spared a most bitter influence”), the Duke of Clarence was troubled by it. His response was to insist that the royal children (King George, Princess Charlotte Louise and Princess Victoria) now be raised as if they were siblings. They were to be accommodated in adjoining rooms and they were to share a household. The Clarences saw the children every day and in school holidays, they took them to stay at the Royal Pavilion in Brighton where the children were allowed to swim in the sea and play on the beach. Prince Leopold arranged for the Coburg princes to return in the summer of 1829 and though the Duke of Clarence had to return to London, he leased a townhouse on Brunswick Terrace overlooking the sea front so that the royal children (accompanied by the Duchess and a handful of servants including Honest Billy) could extend their stay at the seaside. Stockmar objected to this. He believed that the King was now old enough to be directly involved in some of the big debates of the day and he had envisaged allowing King George V to attend parliamentary debates concerning the Roman Catholic Relief Act. The Duke of Clarence refused to bend to Stockmar on this occasion and whilst emancipation was debated in Westminster, the King paddled in the sea.

The Duke of Clarence had his concerns about the proposed relief act and this necessitated his return to London from Brighton, where no doubt he would have preferred to have stayed. As promised, the Duke of Wellington had met with Daniel O’Connell to find a compromise to the emancipation issue. The proposal was to introduce two bills; the Parliamentary Elections (Ireland) Act and the Roman Catholic Relief Act. Whilst the latter repealed the Test Act 1872 and the remaining Penal Laws in Ireland, in Westminster it allowed members of the Catholic church to sit in parliament. Daniel O’Connell could therefore finally take his seat in the Commons. But there was a sting in the tail. To get the bill through the Lords, the Parliamentary Elections Act had to accompany it. The legislation disenfranchised minor landholders in Ireland and raised the economic qualifications for voting. Whilst Roman Catholics could now sit at Westminster, the Parliamentary Elections Act made it unlikely they would be elected in the first place.

Wellington was determined to see the bill through, even going so far as to stake not only his premiership but his life upon it. When the Earl of Winchelsea accused the Duke of “an insidious design for the infringement of our liberties and the introduction of Popery into every department of the State”, Wellington challenged him to a duel. They met on Battersea fields, the Prime Minister firing wide to the right in a delope and Winchelsea firing into the air rather than at the Duke of Wellington. Honour was served and Winchelsea was forced to publish a grovelling apology. Now dubbed “the Iron Duke” by the popular press, even the Ultra Tories had to concede that Wellington had proved his intentions were honourable and the Parliamentary Elections Act offered many parliamentarians who had sat on the fence thus far the security they needed to support the Relief Act. The bill narrowly passed and however reluctant he may have been to do so, the Duke of Clarence gave it Royal Assent on behalf of the King.

A popular cartoon shows Daniel O'Connell being celebrated by the poor of Ireland, perhaps ironically.

In the short term, all parties seemed content with the compromises made but it didn’t take long for things to unravel. In Ireland, O’Connell was scorned for going back on his word. Whilst he tried to rationalise the Parliamentary Elections Act to his constituents, across Ireland many spoke out against O’Connell for what they regarded as disenfranchising them for his own self-interest. The Elections Act reduced the Irish Catholic electorate from 216,000 to just 37,000. The tariffs and fees to be paid by candidates and voters alike meant that the vast majority couldn’t afford to participate in elections and thus, O’Connell was accused of abandoning the rural masses for the gentry of Ireland. The French philosopher and diplomat Alexis de Tocqueville noted a pamphlet published by the Ribbonmen; “We have a little land which we need for ourselves and our families to live on, and they drive us out of it. To whom should we address ourselves? Emancipation has done nothing for us. Mr. O'Connell and the rich Catholics go to Parliament. We die of starvation just the same”.

In London, Wellington was congratulated by many parliamentarians for achieving what many considered impossible. But as he dined with colleagues at Apsley House and toasts were given to peace in Ireland, a revolt in the Tory Party seemed inevitable. Led by the Duke of Newcastle, the Ultra-Tories (who perhaps had never foreseen that emancipation would actually become a reality) banded together and made a private pledge to derail any further attempts at constitutional reform. Come hell or high water, Wellington would not be able to convince them otherwise and the divisions that had erupted in the last two years now came to a feverish head. Wellington had a majority in the Commons (albeit a slightly reduced one from that of Lord Liverpool) and a general election was several years away. [3] Newcastle and his allies in the Lords and Commons began to hold a series of private meetings at which a Vote of No Confidence in the Prime Minister was proposed as a tool to oust Wellington. Meanwhile, Wellington, not so naïve as to believe his party divisions would now be forgotten, began to assemble his strongest allies in parliament. The Iron Duke was about to fight the greatest political battle of his life.

[1] This follows the OTL with Blore replacing Nash in 1829/1830.

[2] See King George IV, Part 5 of this TL.

[3] This is notably different from the OTL (mostly because of Liverpool's early departure and the lack of an 1830 general election) and it's where British politics will begin to shift and change quite a lot in this TL.