You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Crown Imperial: An Alt British Monarchy

- Thread starter Opo

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 131 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

GV: Part Four, Chapter Five: Looking Away GV: Part Four, Chapter Six: Brothers and Sisters GV: Part Four, Chapter Seven: Mothers and Sisters GV: Part Four, Chapter Eight: An Answer to Prayer GV: Part Four, Chapter Nine: Kings and Successions GV: Part Four, Chapter Ten: Cat and Mouse GV: Part Four: Chapter Eleven: Secrets and Lies GV: Part Four, Chapter Twelve: Life at Lisson* fingers crossed for a Christmas Special *

"Get outta mypubpalace"

But this does give me an opportunity to say a huge thank you to everyone who has been following this TL over the last three months, it's lovely to see so many of you engage and enjoy it. I hope you all have a very happy and peaceful Christmas and I'll be back with more 'Tantrums & Tiaras' in the New Year.

King George V

Part One, Chapter Thirteen: A King-in-Waiting

Part One, Chapter Thirteen: A King-in-Waiting

In the Autumn of 1833, the King’s tutor, John Lawton, asked to be allowed to retire. At 76 years old, he had never expected to leave King’s College, Cambridge, much less to serve the Sovereign. Whilst Baron Stockmar’s departure had seen him take on a prominent position in the Royal Household, Lawton had never cared for the trappings of court life and was visibly uncomfortable at the grand occasions he was expected to attend. King George V was deeply upset when Lawton announced that he would be retiring at the end of the year but his time with his tutor had been well spent. Lawton’s final report to the Duke of Clarence was a glowing one. The 13-year-old King was; “bright and capable with a healthy curiosity that will serve him well. He respects authority but does not exert his own. He still shows little aptitude for poetry and he does not appear at all interested in great literature or works of art. Yet he is diligent and studious in keeping his journal and he shows a keen interest in history and philosophy, seeking out books on these subjects which he devours quickly but comprehends perfectly”.

A young King George V by Sir Martin Shee.

Lawton had done his duty and his protégé had survived the strict Stockmar system only to prove how useless that particular approach was once it was over. John Lawton was given a pension by the Royal Household and a grace and favour cottage on the Windsor Estate where he died in 1845 at the grand old age of 88. In his journal, the King noted; “Mr Lawton died this morning. I shed a tear for my old tutor and friend who was such a model to me and a true credit to his profession”. With Lawton’s resignation, it was decided that the King’s education would be broadened from the usual syllabus he might have followed at Eton College. Whilst his lessons would still continue, these would be entirely focused on subjects such as the British constitution or current world affairs. These lessons would be limited to four hours a day, three days a week and would be led by a tutor appointed from King’s College on John Lawton’s recommendation, Henry Barwell.

Barwell had a reputation as something of a radical, a man with a reforming zeal who believed that the education system in England was “a stain on its character”. The Duke of Clarence was initially troubled by Lawton’s recommendation but after meeting Barwell, he considered him “a fine man and if concern for the welfare and better education of the gentlemen of tomorrow be a radical position, I might then be declared to be radical also”. Barwell believed that books and lectures could only go so far and he advocated regular outings away from the classroom so as to allow his pupils a first-hand glimpse of the world outside of the school walls. For the young King, this coincided with the government’s view that he should begin to undertake a limited programme of public engagements from his 14th birthday onwards so as to better introduce him to the people. Barwell believed the King “mature and sensible enough to carry off such appearances with tact and amiability” and so a programme was put together with London providing the setting for the King’s “Spring of Introduction”.

The first of these visits was to the Palace of Westminster for a personal tour conducted by the Speaker of the House of Commons. Whilst he was intrigued to see the throne in the Lords chamber (The Times noted that His Majesty did not try it for size), he thought the Commons to be “in much better order” and impressed the Speaker, Sir Charles Manners-Sutton when he said he was pleased to be able to visualise the chamber better in future when he read Hansard debates. At the close of the visit, the House of Commons assembled to applaud the King who was said to have “conducted himself with an interest and sensibility far beyond his years”. As a token of his gratitude, the King commissioned Garrards & Co to produce a new mace for the House of Commons, replacing that which was given to the House by King Charles II following the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660. When it was presented to the Commons, the House received it with a Loyal Address thanking His Majesty for the gift.

The House of Commons as it was at the time of King George V's visit in 1834.

There were also visits to the British Museum and to the Royal Academy of Arts, the Royal Society and the Tower of London. On a visit to Westminster Abbey, the King caused a minor stir when he was offered the opportunity to pray at the Shrine of St Edward the Confessor. Not wishing to insult his hosts, the King knelt for a few moments but then popped back up and wandered over to the tombs of Elizabeth I and her sister Mary, which he was far more interested in. This was the first indication that the King would never truly embrace his role as Supreme Governor of the Church of England. His religious beliefs were possibly best described as non-conformist and whilst he never shirked his religious duties, he often spoke of the Anglican Communion and his position within it as “that other thing”, uncomfortable with long religious services and with some of the beliefs of the more Anglo-Catholic Bishops he met with frequently. He would later write; “I see more opportunity to worship the Divine in nature than in cathedrals”. Indeed, as he grew older, he dispensed with early morning prayers in the royal chapels and preferred to start his day with a walk in the gardens of his residences accompanied by a more junior cleric. They would pray but mostly discussed a psalm or a parable together, the King often surprising those who joined him with his “scholarly knowledge of the life of Christ”.

Until his 14th birthday in January 1834, the King had never left England. Barwell believed that he should visit the continent so as to allow him “a glimpse of a country which is not his own and so to have an opportunity for comparison and even critique”. It was decided therefore that the young King should visit Hanover. George’s grandfather, King George III, had never made the journey and the last British Sovereign to visit “the other Kingdom”, was King George II. For George V, this was an exciting prospect, not only because he would experience foreign travel for the first time but also because his predecessor had become a personal hero. Kneller’s portrait of the late King was hung in his bedroom and he even took to wearing a miniature of George II on a blue ribbon around his neck. He also commissioned a biography of King George II but when he was unhappy with the first drafts (which he felt “failed to appreciate the truly remarkable achievements of the man”), he pledged to write the book himself in the future.

George V would also have an opportunity to see the country which had given the world another of his heroes; Frederick the Great. After visiting Hanover, the King’s party would move on to Prussia where George would watch military manoeuvres, visit the King of Prussia at Schloss Charlottenburg and tour various important landmarks in Berlin. He insisted that a trip to Potsdam be included in the itinerary so that he could visit the tomb of Frederick the Great at the Sanssouci. Barwell proposed that the return to England might be made via Paris but the British government vetoed the idea on the grounds that the French had recognised Belgium and Britain had not, and King Louis Philippe was likely to invite King Leopold, putting the young King in an awkward position. Instead, the King would first sail aboard the Royal George (the Royal Yacht) to Holland where he would visit the Prince and Princess of Orange and the Dutch King before moving on to Germany. Joining him on his voyage would be the Duchess of Clarence and Princess Victoria of Kent who would remain in The Hague until the King’s visit to Germany was concluded and the pair could join him to return to England.

The King’s European tour was planned for August 1834 but in the meantime, the success of the domestic visits in London prompted Barwell to schedule more of the same. However, one of his ideas was considered a little too political to be approved. In 1833, the Whig government introduced the Factory Act. Led by Lord Althorp, the act was the response to the reports issued by a commission which had spent months touring the textile districts. Their findings proved shocking. Factories and mills were found to be “places of the most vile immorality” where children were found to be working in terrible conditions and were being subjected to regular beatings by overseers determined to work them harder. Whilst conditions for so-called “mill children” were far preferable to those experienced by children working in mines or other industries, the government wished to address the situation in factories and mills as a priority. Althorp’s bill made it illegal to employ children less than 9 years old in factories (they could still be employed in silk mills and other industries) and child workers of 9 – 13 years of age were limited to 9 hours a day. There had been previous acts implemented by other governments which sought to regulate working conditions for children but the Factory Act of 1833 proved particularly controversial, not just with factory owners or investors, but also with the working classes who feared a significant loss of income.

Barwell felt that the King should see the life he might have had by visiting a factory employing children his own age and even suggested he be allowed to meet with some of them, rather than being given a tour by the factory owner whom no doubt would put only the very best side of his operation forward. “In my view”, Barwell wrote to the Duke of Clarence, “This visit would allow His Majesty to see a perfect example of how current legislation affects the lives of his subjects directly and would, I believe, give him an appreciation and understanding of the working conditions faced by many of them”. This was a step too far for the Duke of Clarence. Whilst the government were not opposed, Clarence forbad the factory visit on the grounds that it was “far too political”. But Barwell found another way to give the King first-hand experience of the life of the working man. He arranged for the King to spend one day a week with Mr and Mrs Robert Larman and their three children on a dairy farm on the Windsor Estate. The King helped Mr Larman with everything from managing the farm accounts to mucking out the cowsheds. At the end of the long working day, George was given a farthing, the wage a farmhand of his age could expect to receive each day for his labours.

The Royal Dairy at Windsor.

This was a lesson the King never forgot. He wrote that he found it “particularly cruel that those who labour most are so often so poor” and from his 14th birthday on, he would make a special effort to visit the farms on his estates to ensure that the families there knew he appreciated their work. As he grew older, he gained a reputation among his tenants for being “the most generous landlord in England”, though other landowners scoffed and jeered at his tendency to overpay and overlook lapses in rent payments. Unable to do anything politically, this was George’s way of showing his commitment to improving the lives of the working poor and though he did not share his grandfather’s interest in agriculture, his tenants often referred to him as “Farmer George the Second”. But the King’s primary interest remained with the military and his upcoming visit to Europe highlighted a problem which the Duke of Clarence had long mulled over. On his visit to Prussia, King Frederick William III wished to appoint King George V an Honorary Colonel of a Prussian regiment for which he would wear a Prussian uniform. One day, George would be Head of the Armed Forces and whilst his father’s life had been devoted to the military before his unexpected accession in 1820, his son looked likely to follow George III’s example and wear military uniform only as a royal costume.

King George IV had been very clear as to the path his son should take where the military was concerned. After having successfully completed three years of afternoon classes, the Prince of Wales was to begin a gruelling schedule of further study designed by Baron Stockmar which would prepare him for Eton College. From Eton, he would undertake a period of military training pursuant to a military career, either with the 2nd Life Guards Regiment of which King George IV had once been Field Marshal or in Hanover where his position might not precede him as much as it would in England. By the time he was 18 years old, the Prince of Wales would be a fully rounded King in Waiting and granted an estate of his own with a view to marriage, heirs and begin a gradual march towards the throne. 1827 had changed all that.

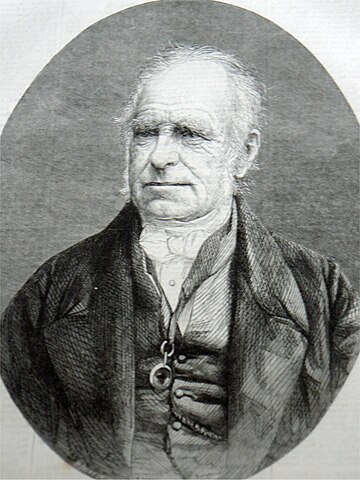

General Lord Hill (Rowland Hill, 1st Viscount Hill)

There was clearly no question of the King ever having a “proper” military career, something the Duke of Clarence recognized would cause great disappointment in his nephew. George V had an insatiable interest in military history from a young age, indeed, he could already outfox several elderly Generals recalling the names and dates of important battles which prompted General Lord Hill to remark; “At 14 years old, His Majesty could command the troops just as well as George II and then write an account of the battle that would inspire every soldier in the British Army for a hundred years to come”. But it seemed that much like his late uncle, the Prince Regent, and his grandfather King George III, George V would be denied the relationship with the military he truly wanted. The Duke of Clarence felt this to be a ridiculous arrangement and he asked Captain “Honest Billy” Smith for advice. Smith felt that an opportunity was being missed to offer the young Sovereign an experience that would “undoubtedly forge a long-lasting respect and appreciation for the British Army whilst also building a mutual affection between King and soldier that will prove invaluable”.

The King met the minimum standards of education for new recruits in the British Army but needed some proof of higher education to be considered for the 18-week officer training programme which had been reformed by his father, King George IV, when he was Commander in Chief of the Forces. Whilst there had always been a view that the King could not be examined, Barwell felt this an important goal for George who may risk losing interest in his formal education now that more exciting projects were being put in his path. The young King was promised that if he completed his higher examinations over the next two years, he would be allowed to attend the Royal Military College for a time and ultimately be gazetted as an officer. This proved a popular motivational tool and the King now applied himself to his studies with a renewed interest and vigour. Honest Billy was also asked by the Duke of Clarence to help show George what the life of a soldier was really about and so Smith spent one day a week with the King demonstrating and how to clean his boots, how to wear his uniform and how to clean a rifle. Honest Billy was promoted to the rank of Major and appointed as an Aide-de-Camp to the Sovereign. He was given special responsibility to help introduce George V to important military personnel, to take him on private tours of barracks and military colleges and even to arrange for him to watch military manoeuvres at home and abroad.

Whilst her brother was being introduced to the various themes of his future role, Princess Charlotte Louise declared her life before marriage to be “an endless round of very dull days”. The Duchess of Clarence wished Princess Victoria to make a good impression when they visited the King and Queen of the Netherlands in the Autumn of 1834 and so the Princess was being given extra lessons with a Dutch professor from Oxford, Floris van Tonder. Van Tonder taught Victoria some rudimentary Dutch, gave her a general overview of Dutch history and schooled her in who the most prominent courtiers were at The Hague. This meant that Princess Charlotte Louise found herself at a loose end, her own education considered to be an end and the corridors of Windsor empty of company. Her one outlet came in the form of letters from Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. Their correspondence had become more regular in the last year and there was no doubt that Charlotte Louise had begun to reciprocate Albert’s teenage crush. But the Coburg princes visited far less frequently nowadays and it became clear to the Duchess of Clarence that Charlotte Louise needed company to alleviate her boredom.

The Duchess consulted her ladies in waiting and asked the Marchioness of Lansdowne to draw up a list of girls who were of a similar age to Princess Charlotte Louise. In the spring of 1834, four of these girls were invited to Buckingham Palace to take tea with the Duchess of Clarence and Princess Charlotte Louise. Of these four, one guest in particular would become a life-long companion to the Princess. Lady Anne Anson was the daughter of Thomas Anson, the 1st Earl of Lichfield, and his wife Louisa Phillips. Two years younger than Charlotte Louise, Lady Anne was known for her bright disposition and her quick wit. The friendship was formed almost immediately and the Countess of Lichfield was appointed a lady-in-waiting to the Duchess of Clarence by the Prime Minister so as to allow the Ansons more time at court. Madame Fillon took the girls on various outings and they even holidayed together in Brighton. For the next 62 years, Charlotte Louise and Anne Anson would be the very best of friends, despite the distance eventually placed between them following Charlotte Louise’s marriage in 1840.

The HMS Royal George, the King's Yacht.

In the first week of August 1834, King George V traveled to Harwich from Windsor Castle to board the HMS Royal George. Accompanied by his aunt, the Duchess of Clarence, his cousin Princess Victoria of Kent, the Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston, Honest Billy and various other senior courtiers. For Lord Grey, Viscount Palmerston’s absence was something of a blessing. A former Tory who had defected to the Whigs in 1830, Palmerston had always been an ally of Grey’s but recently he had shown sympathy with those in the party such as Lord Melbourne and Lord John Russell who were displeased with Grey’s approach to Church Reform and a lack of clear direction on Irish issues. Whilst many Whigs caustically remarked that Grey threatened to resign almost on a daily basis, this time he was seriously considering whether he should make way for a new man. But he wanted time to gauge the support he had in Cabinet and whilst Palmerston made it clear that the Prime Minister would always have his personal support, Grey doubted that the Foreign Secretary would maintain this loyalty if it seemed likely the top job could come his way. With Palmerston out of the country, Grey felt better able to assess his options and consider his future.

The Royal party sailed to Rotterdam on the 4th of August 1834 and were met by the Mayor, Marinus van IJsselmonde, and Prince Frederick of the Netherlands, King William II’s younger brother, and Frederick’s wife Princess Louise daughter of King Frederick William III of Prussia whom George V would shortly be visiting in Berlin. The Prince and Princess escorted the British visitors to the Noordeinde Palace in The Hague. The welcome ceremony saw King William II present the royal guests with a vast array of gifts, including a diamond and ruby brooch for Princess Victoria in the shape of her initials ‘AV’ (for Alexandrine Victoria). For King George V, there was a series of books from the Batavian Society for Experimental Philosophy, a silver jardiniere engraved with the coats of arms of the Dutch and British Royal Families and the insignia of a Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Netherlands Lion. King George V returned the favour by appointing the Prince of Orange a Knight of the Order of the Garter and presented his wife with a diamond aigrette which she wore at the welcome banquet that evening at the Palace.

There were gifts too for Prince William of the Netherlands and his household. The Dutch Court were under no illusion as to why Princess Victoria had been included in the visit and she later wrote that she felt she had been “sent on approval”. Whilst for the most part the Dutch court were welcoming and friendly, some of Princess Anna’s ladies were less than impressed with one commenting that Victoria was “not at all attractive”. Court gossip made frequent reference to her mother’s “insanity” and there were those who even doubted Victoria’s legitimacy and claimed that she was John Conroy’s daughter. This led to Victoria being dubbed “the little Conroy” at the Dutch court. When the Prince of Orange heard this, he dismissed those responsible and banned any talk of Victoria’s parents, though there is no evidence to suggest that he ever believed the allegations which were clearly false.

The Noordeinde Palace today.

The Duchess of Clarence and Princess Victoria were housed in a suite of rooms at the Noordeinde Palace which both agreed were impeccably designed. Whilst the Dutch constitution decreed that the State must provide both a summer and winter home for the Sovereign, King Willem I never resided there and immediately after the welcome banquet, the Prince of Orange and his wife returned to the Kneuterdijk Palace with their children. In between scheduled visits to the Missionary Society and the Mauritshuis, the Duchess of Clarence and Princess Victoria took a carriage ride to the Kneuterdijk where they spent most afternoons in the company of the Queen. Prince William was initially reluctant to join them, possibly a little embarrassed as his mother’s obvious matchmaking. However, he did comment to his brother Alexander that he found Victoria “an enchanting girl with very beautiful eyes” and slowly, he felt more comfortable in her presence. Victoria’s first impressions of the Prince did not change. She still felt him “dull and somewhat exhausting” and complained that “he never starts a conversation and when he does join in something like a game, he is too slow and stupid to offer anything of real interest or wit”.

For the most part, Victoria conducted herself well, though eyebrows were raised when she (quite innocently) mentioned her uncle whom she referred to as “King Leopold”. This earned a sharp rebuke by Prince Frederick who snapped, “He is not King here!” but this minor oversight was ignored when Victoria showed off her excellent grasp of conversational Dutch. Princess Anna was deeply impressed once again but she was concerned that Victoria seemed far more comfortable in Prince Alexander’s presence than in the company of the Prince of Orange. Alexander was therefore sent to Soestdijk for the remainder of the visit. The Duchess of Clarence wrote a letter to her husband back in England offering a promising report; “William and Drina seem more comfortable together, though I fear he remains a little intimidated by female company which is to be expected. I believe Victoria likes him well enough, though she is so tired at the end of our days here that we do not discuss the matter much”.

Meanwhile, King George V was making his way to Hanover. There was a natural curiosity among the people there and many hoped this visit would mark a change in the relationship that had previously defined the personal union between the two countries. Neither George III nor George IV had visited as monarch and though the King’s mother had left the country to the relief of those at Herrenhausen, her son was far more welcome. The gardens in the front of the palace played host to the great and good of Hanoverian society and the King, escorted by his uncle, the Duke of Cambridge, was introduced to his subjects in Hanover for the first time. One amusing encounter was a reunion with Baron Stockmar. Stockmar bowed politely and immediately asked how the King’s studies were progressing. The King replied curtly; “They are far more enjoyable now than they once were” before walking away. Stockmar was left red-faced and noted in his journal that day that the King had “lost none of his strong will and petulance”.

The Gardens at Herrenhausen.

On the King’s first evening in Hanover, Herrenhausen played host to a grand family reunion. Many of his relatives scattered throughout Germany had been invited to join the banquet welcoming George to Hanover and it was here that George met many of them for the first time. Some would join the royal party and travel to Berlin too, giving the King the opportunity to get to know them better. Of the guests present, two would become important figures in the King’s later life. The first was his cousin, Prince George of Cambridge, the only son of Prince Adolphus and Princess Augusta. Dubbed “the Two Georges”, George Cambridge was to return to England with the royal party to continue his education in England after his summer holidays and the King would ask the Duke of Clarence if his cousin could move into Windsor Castle so that the two friends could spend more time together. The other notable guest who would become a close friend to the King throughout his life was Prince Alexander of Prussia, the son of Prince Frederick of Prussia and Princess Louise of Anhalt-Bernburg.

Alexander was shortly to begin his army career and this fascinated George who proudly boasted that he too would enrol in a military college when he turned 16. He was somewhat jealous that Alexander would have a head start on him but nonetheless, the pair kept up a correspondence and some time later with their own households established, Alexander became a frequent guest at Windsor. Likewise, George V would spend his holidays in Switzerland where Alexander had a large estate, but also in Trechtinghausen where Alexander had a castle, Burg Rheinstein. Meeting Alexander was not the only high point of the King’s visit to Berlin. He was greatly enthused by the military manoeuvres staged for his enjoyment and he was thrilled to be named an Honorary Colonel of the 1st Foot Guards Regiment, the infantry regiment of the Royal Prussian Army formed in 1806 and to which all Princes of Prussia were commissioned lieutenants on their tenth birthdays. The ceremony took place at the Sanssouci in Potsdam where King George was able to visit the tomb of Frederick the Great and where he was also presented with the insignia of a Knight of the Order of the Black Eagle by King Frederick William III.

But there was an unexpected surprise at Sanssouci for the King during his visit too; he fell in love for the first time. The object of his affections was the 17 year old Charlotte Bodelschwingh, a niece of Ernst von Bodelschwingh auf Velmede, then serving as Oberpräsident of the Rhine Province. Charlotte was presented to the King during his visit to Sanssouci and in his journal, George wrote that he had “never seen a beauty so glorious” as he saw in Charlotte. Through Honest Billy, George managed to obtain a small sketch of Bodelschwingh which he brought back to England with him and placed in a frame beside his bed. He began to write letters to her, proclaiming his undying love and deep affection for her. This was nothing more than a boyhood crush of course and Bodelschwingh was advised by her uncle not to reply. George was heartbroken and begged Honest Billy to help him escape Windsor so that he could head for Potsdam and “rescue my great love”. Fortunately, the King’s first experience of love did not sting for too long but he often referred to “that pretty girl at Sanssouci” as an adult and was amused to learn that she had later married a Lutheran pastor; “And to think, her uncle considered me an unsuitable prospect!”.

The South Facade of the Sanssouci, Potsdam.

The Royal party returned to England in the first week of November and foreign travel had clearly made an impression on the young King. He spoke of nothing else but his trip for weeks, leading to an unfortunate incident at the funeral of Prince William Frederick, Duke of Gloucester and Edinburgh a few weeks later. The Duke died on the 30th of November 1834, leaving behind his widow Princess Mary, his first cousin and George V’s paternal aunt. Following the burial, the Royal Family gathered for a luncheon where the young King spoke at length on how wonderful Hanover had been to visit and how proud he was that he was also King there too. This wasn’t exactly the most diplomatic subject to discuss as the late Duke had been excluded from the House of Hanover because of the unequal nature of his parents’ marriage. The Duke’s sister, Princess Sophia, was deeply offended (she too being excluded from the genealogical listing of the electoral house of Hanover in the Königlicher Groß-Britannischer und Kurfürstlicher Braunschweig-Lüneburgscher Staats-Kalender). She returned to her home at Rangers’ House in Blackheath in high dudgeon and declined an invitation to spend Christmas at Windsor with the Royal Family.

Whilst the death of the Duke of Gloucester and Edinburgh did not overly affect the King, the Duke of Clarence was deeply troubled by it. He was ten years older than the Duke of Gloucester and was fast approach 70 years old. His health was beginning to decline and he felt increasingly exhausted by his duties at regent for his nephew. His deputy, the Duke of Cambridge, was no spring chicken either, having turned 60 that year. George IV’s will had only named Clarence and Cambridge as regents and whilst the Duke of Clarence trusted the government to provide his nephew with a suitable successor should both his uncles die before he reached the age of majority, Clarence asked the Prime Minister to agree whom that successor should be before the turn of the New Year. With the Duke of Cumberland out of the running, only the Duke of Sussex was left of the sons of King George III and Clarence wished to avoid the possibility of parliament appointing a regent from the House of Lords or the Royal Household if there was a vacancy. But Clarence wasn’t the only member of the family pondering the future. At Rumpenheim, someone else was considering what it may hold and was making plans accordingly. 1835 would see those plans put into action.

Note

Apologies but I can't seem to add a threadmark to this post. I'll try again later and hope it takes as I know this is helpful for readers!

Last edited:

Of course he wasn't, I've got my Georges and Fredericks confused here. I'll correct!George III's father wasn't George II.

Last edited:

Not to gush and make you blush, Opo, but you're doing a fantastic job with this timeline. Sure enjoying it!

That's very sweet of you, thank you so much!Not to gush and make you blush, Opo, but you're doing a fantastic job with this timeline. Sure enjoying it!

Not to gush and make you blush, Opo, but you're doing a fantastic job with this timeline. Sure enjoying it!

I think it's a shoe-in for the awards in the new year for me.

I think it's a shoe-in for the awards in the new year for me.

Goodness me, that really is very kind of you both. Thank you so much for reading and I'm very glad you're enjoying my work here!I would vote for it.

GV: Part 1, Chapter 14: The Queen Returns

King George V

Part One, Chapter Fourteen: The Queen Returns

In the latter half of 1834, Queen Louise left Rumpenheim for Schloss Neustrelitz, the home of her sister Marie and Marie’s husband, Grand Duke George of Mecklenburg-Strelitz. Louise had grown tired of life at Rumpenheim, the warm reception she had expected on her homecoming found wanting as her elderly father and her eldest brother William showed more sympathy with the British Royal Family than with her. Louise’s niece, the future Queen consort of King Christian IX of Denmark, recalled her aunt’s final days at Rumpenheim; “Nobody in the family much cared for her by that time. She was full of complaints and she insisted on taking precedence over my mother because she was the Queen of England (sic) which caused much unpleasantness. She meddled in everything. I recall my mother being very upset when she dismissed servants she did not like and my father eventually made it clear that Aunt Louise was no longer welcome at Rumpenheim”.

A postcard of Neustrelitz Palace, c. 1920.

Louise also recalled the weekly tea parties her aunt would host in the salon of Rumpenheim for her nieces and nephews; “We all dreaded them. She reduced my sister Augusta to tears because she saw she was a shy child and she always told us that we were very beastly children who made too much noise so she could not sleep in the afternoons as she liked to do. We always tried to make excuses not to be in her company but she had a curious way of commanding a person that made you feel you dare not oppose her. I’m afraid we all grew to despise her and that is perhaps why she became even more bitter and cruel. She might have otherwise been a cherished member of the family but I am certain she enjoyed being so ghastly. I only met her a few times after my marriage but on each occasion she was sure to say something horrid which would upset somebody and so we stopped offering invitations. We simply could not bear to be in her company”.

Of all her siblings, the only one she had managed to maintain friendly relations with was her younger sister Marie and so it was in August 1834 as her son arrived in Europe for his first tour that Queen Louise was once again on the move. She arrived totally unannounced at Neustrelitz and immediately caused chaos. Schloss Neustrelitz was not a particularly large residence (by palatial standards of the day) and the Grand Duke and Grand Duchess had four children who were all of an age where they had left the nursery for rooms of their own. Life at Neustrelitz would be something of a squeeze and as at Rumpenheim, Louise’s haughty demeanor caused upset in the household of the Grand Duke. She replaced servants, changed menus and altered mealtimes and like their cousins, Marie’s children were summoned once a week to take tea with their aunt which they found a chore. But Marie Strelitz was endlessly forgiving. A woman who tried to see the best in everybody, she would make excuses for her sister’s behaviour and withstood Louise’s imperious demands and brutal rudeness. Marie's daughter Caroline later said; "My mother was powerless where Aunt Louise was concerned. She always gave in to her. Always".

Marie of Hesse-Kassel, Grand Duchess of Mecklenburg-Strelitz.

By this time, Queen Louise knew she could not stay in Germany much longer. Her allowance had once again been cut and whilst the Duke of Clarence had settled her debts, she was quickly descending once more into financial difficulty. But the idea of returning to England intimidated her. Louise was not so foolish as to believe that she could ever recover a meaningful relationship with either of her two children, neither did she believe her brother-in-law was being truthful when he said that past squabbles would be forgiven and forgotten upon her return. The silence of her other in-laws would mean no allies at court when she was finally forced to go back to Royal Lodge at Windsor and she realized that she needed some kind of insurance policy that would give her at least some of the influence at court she had once enjoyed during the reign of her late husband. Ironically, it was King George IV who provided Louise with that insurance policy in his will.

George IV was under no illusion that his wife was deeply unpopular in England and for that reason alone, he had sought to remove her from any position of authority by keeping her as far away from the regency for his son and heir as possible. But this is not to say that he did not love his wife, indeed, he seems to have put distance between Louise and power for her own good. The one responsibility he deemed to be hers by right was that she should be allowed to arrange the marriages of the couples’ children following the precedent set by his mother Queen Charlotte. Until this time, Louise had shown no interest in the matter. The Duke of Clarence had taken up the responsibility where Princess Charlotte Louise was concerned but in his view; “It is for His Majesty to decide for himself when he has reached the age of majority, though he must act quickly in this to secure the succession”. Queen Louise saw an opportunity to return to England with a purpose. Writing to the Duke of Clarence in December 1834, she announced that she would leave Neustrelitz for Windsor in the New Year. “His Majesty’s 15th birthday brings him to an age where a suitable marriage can no longer be a secondary concern”, she wrote, “It is therefore my intention to return to England to carry out my husband’s wishes and find a bride for my son whom he may marry as quickly as possible following his 18th birthday”.

Marlborough House today.

For his own part, the Duke of Clarence intended to honour his promise to his sister-in-law. Upon her return, her allowance would be reinstated in full (from £10,000 per annum to £45,000) and he would welcome her to court as if the battles of the last few years had never occurred. But this would have been far too simple for Louise and naturally she had to find a way to make her return as unpleasant as possible. Whilst she intended to take up residence at Royal Lodge once more, she stressed the importance of having a London residence now that the King was spending more time in the capital. She overlooked its connections with King Leopold and demanded that she be given the use of Marlborough House.

Since the fire at Kensington Palace, Marlborough House had been home to Princess Sophia, the King’s aunt and the youngest surviving daughter of King George III. Initially Sophia had shared Marlborough House with her sister Augusta and her brother the Duke of Sussex but the Duke could not stand the constant bickering between the two spinsters and left Marlborough House for a town house of his own in Belgravia. Augusta had grown so tired of Sophia that she barely spent anytime in London, preferring to remain at her primary residence at Frogmore. Sophia had become used to having the run of the mansion to herself but now, she was asked to move into a small apartment at St James’ Palace so that Queen Louise might move into Marlborough House as a permanent London residence. Regardless of their quarrels, Princess Augusta was furious at the way her sister had been treated and as a form of protest, promised she would never again be in the company of the Dowager Queen.

As the Royal Household prepared for the Queen’s return, one of her rivals would not be there to greet her. Earl Grey had finally made good on a constant threat and on the 17th of September 1834, he traveled to Clarence House to offer his resignation as Prime Minister. Grey was increasingly being seen as “yesterday’s man”, someone more akin to the moderate Tory view than to the pro-reform Whigs and his Cabinet colleagues were becoming frustrated with his lacklustre approach to their agenda. Lord John Russell was heard to ask why, with both Houses of Parliament under their control, Grey did not embark on a legislative agenda that would secure Whig government for another generation. But as Grey had grown older, his appetite for reform had diminished. He could be proud of his achievements in passing the Reform Act and the Abolition Act but now, he found himself frequently agreeing with his Tory foes rather than with his Whig friends. His time had come and Grey opted to retire from frontline politics. He recommended the Duke of Clarence either call Lord John Russell or Lord Melbourne as his successor.

Both men had been allies of Lord Grey but had equally proved to be a thorn in his side in recent months. Russell was known to be an advocate of wide-spread reform, particularly where the Church was concerned, and he believed that Grey was missing an opportunity to take full advantage of the Whig majority in both Houses to deliver a “golden age of progress”. But Russell’s speech on the Irish Tithes Bill had made many of his colleagues nervous. He argued that the revenues generated by tithes justified by the size of the Protestant church in Ireland which many had sympathy with, regardless of the turmoil tithes were causing across Ireland. He alienated many colleagues by adding that a proportion of the tithe revenue should be appropriated for the education of the Irish poor, regardless of denomination. Whilst this view was popular among supporters of Daniel O’Connell, many Whigs were troubled that O’Connell’s support was a poisoned chalice. By 1834, O’Connell had founded the Repeal Association which campaigned to repeal the Acts of Union between Great Britain and Ireland. If Russell was named Prime Minister, Grey had no doubt that his domestic agenda would be beneficial for the country as a whole but warned the Duke of Clarence that his Irish policy may pose a serious rift among the Whigs.

Lord John Russell pictured here in 1861.

By contrast, Lord Melbourne was seen as a compromiser. He had once been opposed to the Reform Act but later supported it as a necessary measure to prevent revolution. However, he was not universally popular within his own party. He had opposed the abolition of slavery calling it “a great folly” and said that if he had been Prime Minister, he would have “done nothing at all”. Again, Grey advised Clarence that Melbourne’s domestic agenda could only be positive for the country but he may divide the Whigs and cause political turmoil. There was a crucial difference between the two candidates Grey recommended; Russell wanted the job, Melbourne did not. Indeed, when he heard that Lord Grey had proposed him as his possible successor, Melbourne said to his secretary, Tom Young; “I think it’s a damned bore. I am in many minds as to what to do”. Young believed his boss to be the best possible successor to Earl Grey and tried to convince Melbourne that he should accept if the offer came his way; “Why, damn it all, such a position was never held by any Greek or Roman; and if it only lasts three months, it will be worth while to have been Prime Minister of England (sic)”. [1] The Duke of Clarence despised Lord John Russell with a passion, branding him “that dangerous little radical”. In his mind, there was no contest. Though they disagreed on many issues, especially Melbourne’s attitude towards reforms in the colonies, out of the two men who might succeed Grey, Melbourne was the most tolerable.

But friends of Russell’s in the press knew that Grey had recommend him to the Duke and they intended to sway Clarence towards their man. The newspapers were suddenly filled with reports about yet another sex scandal to plague Lord Melbourne. It was alleged that Melbourne had been having an affair with the society beauty Caroline Norton and her husband had issued a demand for £1,400 in damages. The case was to go to a court hearing. Initially, the Duke of Clarence did not see why such a scandal should derail Melbourne’s career. But neither could he wait until after the trial. [2] He had to make a decision and appoint a Prime Minister. Though convention would have it that the King (or in this case, the King’s Regent) should make his decision on whom to appoint based on the recommendation of the outgoing officer holder, there was no legal barrier to the monarch or his representative appointing a different candidate altogether.

Initially, the Duke considered Lord Palmerston but he could see no possible successor to Palmerston at the Foreign Office among the Whigs who could boast the same expertise - or whom he could trust. Finally, Clarence found the answer in his own house. Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice, 3rd Marquess of Lansdowne, was a former Chancellor of the Exchequer and Home Secretary who could command the respect of both wings of the Whig party, indeed, even moderate Tories praised his calm and steady approach to the great matters of the day. His wife, Louisa, had been appointed as Mistress of the Robes to Queen Louise but unwilling to go to Hanover, had instead been serving in the household of the Duchess of Clarence. Lansdowne had no great appetite for high office but he felt a personal debt towards the Clarences. He truly believed that there were other men more suitable for the job and he privately noted that “the most important decisions seem to be taken on the personal likes and dislikes of the Royal Family”. Nonetheless, he reluctantly agreed and on the 18th of September 1834, Lord Lansdowne was appointed Prime Minister.

Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice, 3rd Marquess of Lansdowne.

This put the government in a curious position. The country now had a caretaker Prime Minister when it did not need one. Even Lord Palmerston felt the Duke of Clarence had allowed his personal politics to interfere with his approach to government appointments and there was quiet chatter at the dinner tables in political households that the Duke would have dismissed the government entirely had the option been available to him. Lord John Russell referred to Lansdowne as “the Prince’s Pup” and his supporters were none too pleased that Lansdowne appeared to favour a “business as usual” approach as favoured by Lord Grey. Their only hope was that Lansdowne would quickly tire of his new position and during his tenure, they could work together to present just one candidate to the Duke of Clarence as his successor. Other Whigs however were delighted to have a steady hand at the tiller, especially one who did not have the baggage of Melbourne or the reputation of Russell.

Lansdowne has been remembered by history as a particularly weak Prime Minister, partly because of his reluctance to accept the position in the first place but also because despite the large Whig majority in the Commons, he seemed reticent to introduce anything too controversial. Historians have suggested that he only ever felt himself a temporary Prime Minister and that he did not wish to drag himself or his party into debates that he had no interest in seeing through to the bitter end. But his weakness gave his political enemies an opportunity they were not going to allow to slip through their fingers. 1834 marked the start of the so-called “Dirty Campaign”. Over the next 12 months, the Unionists led by the Earl of Winchelsea staged a bitter public campaign against the government (and moderate Tories whom they dubbed ‘the Little Russells’) full of personal attacks and smears on their opponents.

Their claims were somewhat sensationalist but they successfully tapped into the fears of many disaffected Tory voters. By portraying Russell as “the power behind the throne”, Unionist candidates held regular rallies at which they turned to old enemies to encourage anti-Whig (and anti-Tory) sentiments. If the Whigs won the next election, the Unionists claimed, they would begin the dismantling of the Church in Ireland and give in to Daniel O’Connell’s demands for a repeal of the Act of Union. Free of the Irish problem, Russell would be installed in Lansdowne’s place and he would then begin a radical programme of public expenditure, advance a new Factory Act, cut the defence budget and reduce the number of Anglican Bishops in the House of Lords just as the Whigs had done with the Irish protestant clergy in the Church Temporalities Act. But worst still, the Unionists claimed that Russell wanted to re-establish full and formal diplomatic relations with the Holy See. The response from the electorate was (predictably) one of outrage. [3]

The first signs that the Unionist message was having a very real impact on the electorate came in the first week of October 1834. Lord Lansdowne had been invited to a luncheon hosted by the Worshipful Company of Goldsmiths on Foster Lane in the City of London. As he was leaving the luncheon, a young man stepped from the crowd carrying a pistol and took aim at Lansdowne. He fired but missed, his bullet firing through one of the windows of Goldsmith’s Hall instead and doing minor damage to a painting inside. Lansdowne was severely shaken by the assassination attempt and at his trial, Francis Bull, the would-be assailant, claimed that he had seen no other choice but to kill the Prime Minister to “protect England from the Pope”. The Unionists were roundly condemned by the political establishment for inciting violence but the Earl of Winchelsea simply claimed they were presenting the British people with the Whig agenda as it would be under Lord John Russell when he (inevitably, according to Winchelsea) took office.

But by far the most serious consequence of the Dirty Campaign came two weeks later on the 16th of October 1834. At this time, the traditional use of tally sticks had been dispensed with and Richard Weobly, the Clerk of Works, was given instructions by the Treasury to destroy the remaining stocks. Instead of giving them away as souvenirs, Weobly chose to burn the tally sticks in the two heating furnaces under the House of Lords. But the furnaces had been designed to burn coal and not wood. The high flames began to melt the copper flues in the walls in the Peer’s Chamber and by 4pm, those inside the House of Lords could smell burning and feel heat coming up from the floor through their boots. By 6.30pm, a huge fireball burst in the centre of the chamber and brought down the roof. The resulting fireball could be seen from Windsor Castle. Despite their best efforts, firefighters could not bring the blaze under control quick enough to stop the flames destroying both the House of Lords and St Stephen’s Chapel where the Commons had met since 1547. Fortunately, a quick-thinking fireman, James Braidwood (Head of the London Fire Engine Establishment) focused his efforts on saving Westminster Hall. By cutting the roof away that connected the Hall to Speaker’s House, the medieval structure of the building was saved though the worst possible damage had already been done.

The Burning of the House of Commons and the House of Lords, 1834, by J.M.W Turner

The glow from the burning Palace could be seen for miles and news quickly spread through the city that the Houses of Parliament were on fire. Crowds quickly gathered with one journalist noting; “there were huge gangs of light-fingered gentry in attendance who doubtless reaped a rich harvest, and who did not fail to commit several desperate outrages”. The crowds became so large that many hopped into small fishing boats and rowed out into the Thames to get a better view. Among them was the Scottish philosopher Thomas Carlyle who noted; “The crowd was rather pleased than otherwise and they whew’d and whistled when the breeze came as if to encourage the flames. They shouted; “There’s a flare-up for Russell – A judgement for his Popery! A man sorry anywhere I did not see”. [4]

As the flames still licked the building, gossip began to ripple through the crowd. The fire was obviously the fault of Catholic rebels or Irish revolutionaries taking advantage of weak Whig rule, just as the Unionists had warned they would. The crowd quickly became a mob and with no clear target, they moved towards Downing Street where the Grenadier Guards who had been helping to put out the fire at the Palace of Westminster had to struggle to hold them back. The clash did not last long but there were arrests and injuries. The next morning, the Office of Woods and Forest issued a report outlining the damage to the building promising that “the strictest enquiry is in progress as to the cause of this calamity, but there is not the slightest reason to suppose that it has arisen from any other than accidental causes”. The Times even carried the first mention of tally sticks but most were unconvinced. The Unionists claimed conspiracy. In their view, the “Whig press is out to protect the seditious rebels responsible for this terrible crime”. Lord Lansdowne was deluged with anonymous letters, many of them death threats but most urging him to believe them when they said that the fire was an arson attack caused by pro-Russell Catholic revolutionaries. [5]

The Duke of Clarence felt these claims to be “ludicrous ravings” and accepted that the fire had been entirely accidental. He offered the use of Buckingham Palace as a replacement to parliament but MPs declined on the grounds that the building was too small. Instead, they would temporarily sit in the Lesser Hall and Painted Chamber of the Palace of Westminster which had not been destroyed by fire and which were hastily re-roofed and furnished for the State Opening of February the following year. Architect Robert Smirke was engaged to design a replacement for the Palace of Westminster with a Royal Commission formed to make a final decision before building work could begin once. But this was by far the easiest damage to repair. In the fall out from the burning of parliament, a mood gripped the country that saw Whig MPs (and some Tories) become the target of public outrage. Whigs in particular found it difficult to move around the country. One MP reported being pelted with eggs whilst another had his face slapped by a woman in the street.

It was in this tense national atmosphere that King George V celebrated his 15th birthday at Windsor Castle. Though she was now resigned to returning to England, his mother did not coincide her arrival with the festivities. On the 11th of February 1835, the Duke and Duchess of Clarence walked out to the Lower Ward of Windsor Castle, joined by senior courtiers and members of the Royal Household, as a coach rolled through the Henry VIII Gate and came to a slow stop. The coachmen descended, bowing to the Duke and Duchess, then opening the door. Queen Louise stepped down from the carriage wearing a black crepe dress and a large black hat trimmed with white ostrich feathers. The Clarences were said to have performed their role impeccably, the Duke stepping forward to kiss his sister-in-law’s gloved hand and bowing his head whilst the Duchess hovered behind and sank into a deep curtsey. Queen Louise gestured toward the coach. A girl of 17 with blonde hair and bright blue eyes dressed in pale blue silk with yellow flowers in her hair followed.

“My niece…Louise”, the Dowager Queen smiled with a wave of her hand, “She was kind enough to accompany her old aunt on her travels, a great help given that nobody greeted me at Southampton”.

The Duke was momentarily surprised but nodded towards the girl who blushed and offered a curtsy. Without waiting for an invitation, Queen Louise held out her arm and the girl took it, the pair processing up the hill of the Lower Ward to the Norman Gateway and on to the State Apartments. As we have seen earlier, her son King George was not entirely overwhelmed by his mother’s return. But he was momentarily intrigued by the pretty young woman who stood behind his mother during their reunion.

“This is your cousin Louise”, the Dowager Queen said brightly, “She has come to visit you. Isn’t that nice Georgie?”

Duchess Louise curtseyed. George V paused for a moment. Then he walked away. But his mother was not offended by this, indeed, she had possibly expected such a cold reaction from the son she barely knew. Turning to her niece, she said quietly; “Do not worry my dear. The King will like you. I shall make sure of that”.

[1] This exchange was recorded by the diarist Charles Greville. In the OTL, Melbourne was convinced to take the post but here, Clarence offers the post to Lansdowne.

[2] Slight butterflies here. William IV was not keen on many of the Whigs in the OTL (he once said he would rather dine with the devil than any member of the Cabinet) but in the different political atmosphere of TTL, he cannot do as he did in the OTL and try and install a Tory government instead. By moving the Melbourne scandal a little earlier and by considering William IV’s dislike of the majority of Whigs, Lansdowne wins by the process of elimination. It should be noted that Lansdowne was offered the chance to be PM twice in the OTL but refused both times. Here, I believe he would accept reluctantly.

[3] These were all positions which Russell held in the OTL but at this time, they’re nothing more than quotes from speeches he gave in Commons debates. It’s unlikely Clarence would ever call Russell as PM but the Whigs in TTL can’t say that to the electorate, all they can do is publicly voice their support for Lansdowne and oppose the Unionists. It puts them in a difficult position politically, as the Unionists would want.

[4] I’ve amended this true quote from Carlyle to suit the narrative. The original was directed at the Lords and was proclaimed judgement for the Poor Law Bill.

[5] I’ve used real quotes here to fit the narrative of TTL.

Notes

The Lansdowne Ministry

- First Lord of the Treasury and Leader of the House of Lords: Henry Petty-Fitzmaurice, 3rd Marquess of Lansdowne

- Chancellor of the Exchequer: John Spencer, 3rd Earl Spencer

- Leader of the House of Commons: Sir John Hobhouse, 1st Baron Broughton

- Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs: Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston

- Secretary of State for the Home Department: John Ponsonby, 4th Earl of Bessborough

- Secretary of State for War and the Colonies: Thomas Spring Rice

- Lord Chancellor: Charles Pepys, 1st Earl of Cottenham

- Lord President of the Council: John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham

- Lord Privy Seal: George Howard, 6th Earl of Carlisle

- First Lord of the Admiralty: George Eden, 1st Earl of Auckland

- President of the Board of Control: Charles Grant, 1st Baron Glenelg

- Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster: Henry Vassall-Fox, 3rd Baron Holland

- Postmaster-General: Charles Poulett Thomson, 1st Baron Sydenham

So would I, most definitely!I would vote for it.

Thankyou! I'm so glad you're enjoying the TL!So would I, most definitely!

I think we have found who Louise wants George to marry.“Do not worry my dear. The King will like you. I shall make sure of that”.

I think we can all agree that the poor girl deserves every sympathy at the prospect of Queen Louise for a mother-in-law...I think we have found who Louise wants George to marry.

Two chapters so soon. Very nice.

I'm not sure if this is correct. I assume this is how the quote should be however.

A man more sorry anywhere I did not see."man sorry anywhere I did not see”. [4]

I'm not sure if this is correct. I assume this is how the quote should be however.

Thankyou! Oddly, this is the exact quote as it appears in Carlyle’s work, I assume because he was writing in a Scottish dialect.Two chapters so soon. Very nice.

A man more sorry anywhere I did not see."

I'm not sure if this is correct. I assume this is how the quote should be however.

Her niece, eh? Pretty certain that this is Louise of Hesse-Kassel, the OTL wife of King Christian IX of Denmark. Not a bad match by any means, and I struggle to find other suitable spouses for George V, aside for Princess Sophie of the Netherlands, or maybe even Maria Nikolaevna, the daughter of Tsar Nicholas I of Russia. Of course there are other options too, but those are the ones that sprang up to me, due to their age and significance. Though I assume that the spouse that is wanted for George V has to be of Protestant stock, and likely German.Queen Louise gestured toward the coach. A girl of 17 with blonde hair and bright blue eyes dressed in pale blue silk with yellow flowers in her hair followed.

“My niece…Louise”, the Dowager Queen smiled with a wave of her hand, “She was kind enough to accompany her old aunt on her travels, a great help given that nobody greeted me at Southampton”.

I think the Louise she presents to George is Luise of Mecklenburg Strelitz (daughter of the Dowager Queens sister, Marie), rather than Louise of Hesse Kassel, future Queen of Denmark (daughter of Dowager Queen Louise' s brother, William).

The opening paragraph has a sequence narrated by the future Queen of Denmark, then the next paragraph comments that Louise also stated, and these are about tea parties at Rumpenheim (William's home) rather than Neustrelitz

The opening paragraph has a sequence narrated by the future Queen of Denmark, then the next paragraph comments that Louise also stated, and these are about tea parties at Rumpenheim (William's home) rather than Neustrelitz

Threadmarks

View all 131 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

GV: Part Four, Chapter Five: Looking Away GV: Part Four, Chapter Six: Brothers and Sisters GV: Part Four, Chapter Seven: Mothers and Sisters GV: Part Four, Chapter Eight: An Answer to Prayer GV: Part Four, Chapter Nine: Kings and Successions GV: Part Four, Chapter Ten: Cat and Mouse GV: Part Four: Chapter Eleven: Secrets and Lies GV: Part Four, Chapter Twelve: Life at Lisson

Share: