King George V

Part Two, Chapter Sixteen: Counting Chickens

The Whig election campaign did not get off to the best start possible. To begin with, Lord Cottenham caught a cold and so the entire Whig platform had to be set by Edward Stanley on his behalf with most MPs already on their way to their constituencies with no briefing as to the kind of thing their speeches should contain. To add to their woes, the Tory press began running daily interviews with widows of troops lost at Bala Hissar and with working men who had lost their jobs or faced starvation. In one newspaper, a column appeared entitled ‘Woes of the Whigs’ and kept people up to date with the latest campaign news.

It was hardly edifying political journalism. The ‘Woes’ reported included news that Sir George Strickland, the Whig MP for the West Riding of Yorkshire, had decided to stand in Preston instead; unfortunately, he entrusted the first leg of his journey to the newly created York and North Midland Railway and ended up stuck in a siding overnight missing the first hustings. Another Whig MP, William Marshall, Member for Carlisle, had been pelted with mud during his hustings and when the local magistrate asked why Mr Ernest Willis had done so, Willis replied, “I’d have thrown flour Sir, but none of us have any”.

By contrast, the Tories were enjoying a promising start to their campaign. They were committed to upholding the Corn Laws, but Sir James Graham promised to introduce a mechanism to impose a sliding scale of import duties based on the overall value of goods which would make wheat, corn and other grains more affordable. This was exactly what the Whigs were about to do before Cottenham called a general election and now, Graham took the initiative and the credit. In areas where the workhouses had become full, Graham committed the government to introduce programmes of work for the unemployed and he pledged to release more money from the Civil Contingencies Fund for areas badly affected by food shortages. His message was clear; the Whigs had overspent and had been distracted by Palmerston’s foreign adventures and Russell’s liberal values. Britain must get back on her feet through hard work and self-reliance, but he conceded that the government had a role to play in helping people along a little to “get over the worst of the Whigs”.

Sir James Graham.

That is not to say that Graham had no challenges of his own to face. Though he wanted to fight the election on domestic issues, many demanded to know what Graham would do in relation to the new problems posed by China and the existing power vacuum in Afghanistan. His answer was simple; the Opium trade was to be abhorred (he stopped short of promising to abolish it) and China had every right to stop the import of such a dangerous drug into her ports. Palmerston had promised a war to assert British interests, Graham refused to countenance another expensive foreign policy mistake. He would send a delegation to China to see the Emperor personally and resolve the crisis by treaty, not gunboat.

On Afghanistan, he had been invited to attend the upcoming Brighton Conference at the end of the month and whilst there, he would make it abundantly clear to the Russian delegates that the British would no longer tolerate aggression in British India and that an agreement must be concluded on Afghanistan to prevent any further loss of life (and expense to the Treasury). The relationship with Russia must be “repaired in an atmosphere of trust and goodwill”, he said, “Moving away from the sabre-rattling policies of Lord Palmerston and back to an age of treaties and agreements which press the British interest but do not inflame the United Kingdom’s rivals to act in such a way which forces us to protect those interests with military action”.

The latter pledge was a little optimistic. Lord Cottenham and his ministers would still be in office when the Brighton Conference was held, and Cottenham had only invited Graham as a courtesy. The government may well change in March but until then, it was Lords Melbury and Granville who would lead the British delegation at Brighton. Graham would be there only in his capacity as an interested observer. This was taken up by the Unionists, the biggest challenge to the Tory campaign. However persuasive Graham might be, the Unionists threatened to split the vote and let the Whigs back in with a reduced majority. But the Unionists were still using old tactics to gain support. They insisted that Cottenham would resign the moment the Whigs had a majority, and that Russell would waltz into Downing Street with a raft of policies that would prove nothing short of an attack on the Crown, Parliament and the Church. They said nothing on the food shortages other than blaming the Whigs for imposing harsher restrictions on landlords which had forced estates to raise rents and ultimately, evict tenants.

When it came to the Tories, some Unionists in Whig/Tory marginals hinted that their supporters should “weigh the balance”. It should be remembered that the vast majority of Unionists were former Tories, and, in their view, the Whigs had a safety net in the Repeal Association which could only be undone if the Whigs were crushed at the polls in significant numbers. One Unionist candidate was deselected mid-campaign for publishing a leaflet which told the electorate in his constituency that a vote for the Tories was still a vote for the Unionists as both parties shared the same anti-Whig views. Graham cheerfully remarked; “The Unionists are the best asset we have in acquiring Whig seats” and Lord Winchelsea privately urged his party grandees to cough up more money to circulate copies of a new magazine called

The Unionist to repair the damage done by his own prospective parliamentary candidates

. The pamphlet lasted just three weeks and was quickly shut down when it’s second edition saw the Unionists threatened with legal action for suggesting one Whig MP was a drunkard and that a Tory MP was about to divorce his wife.

At Buckingham Palace, the King continued to meet with Lord Cottenham. Both knew that regardless of the outcome, the Prime Minister’s days in office were numbered and so these meetings were more general in their scope, Cottenham now unable to offer any long-term commitments. The King apologised that he could not invite the Prime Minister to the christening of Princess Victoria in the first week of March; for Cottenham to be seen in the royal presence so close to polling day was unthinkable. This left the King and the Prime Minister only one issue to focus on: Russia. With the Brighton Conference looming ever closer, Lord Melbury had kept the King well informed of what the government intended to propose to the Russian delegation. But George was more concerned at the Russian proposal his sister may be about to receive. If she was right and if the Tsarevich did ask for her hand in marriage at Brighton, the King faced an extremely difficult situation. Whilst the government could not withhold consent for such a marriage, it could still raise objections.

When they had discussed Princess Charlotte Louise’s possible marriage to the Tsarevich before, Cottenham had spoken of Cabinet concerns. Now, George and Cottenham revisited those objections but this time the King was better prepared. He acknowledged that the concerns of Cottenham’s ministry were valid, though before he had disapproved of the way in which they were raised. That being said, the King was not prepared to entertain Lord Cottenham’s suggestion that parliament might introduce a bill which would allow members of the Royal Family to renounce their succession rights. In his view, this would give parliament an authority to involve itself in matters concerning the marriages of the Royal Family (and the succession) which George insisted would set a dangerous precedent; “How long before pressure is applied in parliament to force members of my family to make use of such a bill, simply because parliament does not approve of their marriage whilst the King does?”. Lord Cottenham had not been entirely thorough in his proposal for such a bill, but he agreed with the King that this would be a most unfortunate consequence.

The birth of Princess Victoria had lessened concerns regarding the line of succession. Whilst it was still entirely possible that Princess Charlotte Louise might succeed her brother one day, the possibility looked to be a very remote one.

“If a guarantee were still demanded”, Cottenham reasoned, “I do have another suggestion which Your Majesty may wish to consider”. The King lit a cigarette and took a paper from the Prime Minister. At the top, it read; “Amendment to the Act of Settlement”.

“The Act of Settlement?”

“Yes Sir”, Cottenham explained, “Passed in 1701 to settle the succession to the Crown on Protestants only. It deposed the descendants of Charles I with the exception of Queen Anne and which eventually settled the throne upon Your Majesty’s ancestress, the Electress Sophia of Hanover”

George muffled a sigh.

“Yes, I know all that Prime Minister”, he said tersely, “But what has that got to do with my sister’s marriage?”

Cottenham drew a breath and affixed his pince-nez, looking down at his notes as he put forward his “guarantee”.

“You see Your Majesty”, he began, “The Act of Settlement barred Roman Catholics from the throne. And any prince who married a Catholic was also barred. The concept of course was to uphold Protestantism as the state religion in the person of the Sovereign who is also Supreme Governor of the Church of England. As a man of the law Sir, I would interpret the Act of Settlement as having two distinct consequences; the first being that the succession was settled on the non-Catholic heirs of the Electress Sophia but the second being that the Sovereign must be a member of the Anglican communion”

Electress Sophia of Hanover.

“I don’t follow Cottenham…”

“Well Sir, when you acceded you became the reigning monarch and by definition the Supreme Governor of the Church of England. By taking the coronation oath, you have accepted all conditions attached to it by statute. And that translates, in my humble opinion, to a pledge that Your Majesty will uphold the Anglican communion as the State Church and as Your Majesty’s practised faith. The Sovereign must therefore, again, in my humble opinion Sir, be a member of the Anglican communion. Her Royal Highness, and by default, her children, will not be members of that communion as the Princess will be required to convert to Orthodoxy if she marries the Tsarevich of Russia. Were the Princess to find herself first in line, I believe that is how the Act of Settlement would be interpreted and applied. In short Sir, the Princess could not be crowned unless she reverted to the Anglican faith, neither could any of her children. Thus, personal union between the Crowns of Britain and Russia is impossible”

The King took in Cottenham’s words. He had great respect for the Prime Minister’s legal background and what he said rang true. [1]

“We are placing great store in an anomaly Sir but great legal precedents have been set on such irregularities and if my party were in office if the situation presented itself as described, I would offer Your Majesty some reassurance that if the interpretation was not enough in and of itself, the government would, and I believe I speak for the Tories as well Sir, introduce an amendment to the Act of Settlement which corrected that anomaly and made the position clear without impinging on the rights of the Sovereign to consent to marriages within His Majesty’s family”.

Yet there were still the political objections to consider. Even those who expressed concerns about a possible succession crisis still maintained that such a marriage would lead Britain into an alliance with Russia which no British government could accept, whether Whig or Tory. This was not so easily solved. The King made it clear that he intended to speak with the Tsarevich personally (if he did indeed propose at Brighton) that he could only give his consent if it was made abundantly plain to the Tsar and his ministers that this would be a marriage with none of the usual political obligations which usually featured in royal marriage contracts of the day. This would not be a union between two great Empires; indeed, it would be expressed in the bluntest terms possible that Britain and Russia would continue to follow their respective foreign policies - even when that meant the two nations found themselves opposed to each other. The conference at Brighton aimed to bring those foreign policies into a form of mutual agreement where Asia was concerned but both now and, in the future, Russia could not rely on Britain’s support in military conflicts (or even in every day diplomatic relations) simply because their future Empress was the sister of the British Sovereign. “Politics are to be left to the politicians”, George told Cottenham, “If the Russians will not accept that then I am minded to withhold my consent until they do”.

The Prime Minister nodded his agreement; “Of course Sir, not every royal marriage is political in nature. And I am appreciate of Your Majesty’s reassurance on this point which I believe is a very sound and sensible view to take. I only hope the Russians can appreciate it too. But I must ask Sir…do you really believe the Princess will be happy in Russia? I hope Your Majesty will not consider me intrusive, but I am fond of the Princess, as are we all in Cabinet, indeed we wish her every happiness. But I cannot believe she will truly find her happiness in St Petersburg”

This worry had crossed the King’s mind too. After all, what did his sister really know of life in Russia? Could she ever truly accept and embrace her new country, her new family and her new religion when all three were so different to what she had experienced in her homeland? The King was determined to make the Princess think seriously about accepting the Tsarevich not because he wished to dissuade her in any way but rather because he feared she may be trying to grasp her first real chance of happiness since her disappointment over Prince Albert. Such a kneejerk reaction might well lead to her a life of misery. That said, if the Princess really was sure, the King was determined to give her what she wanted. He would fight tooth and nail to prove to the naysayers that her marriage would not lead to catastrophe…but only if he believed she was sincere in her feelings. It was Cottenham who offered a solution.

“I have taken an interest in this matter Your Majesty”, he said kindly, “And if I may…has Her Royal Highness actually met with any Russian who isn’t connected to the Imperial Family? I’m not speaking of Count Medem or the like. Rather, someone who could give her a more subjective view of the country?”

The King laughed, lighting another cigarette, “As unusual as it may seem Prime Minister, we do not often entertain Russian peasants here at the Palace”

“No Sir”, Cottenham said, not quite catching the King’s joke, “Now as I recall, there used to be an Orthodox congregation in Greek Street – hence the name. Their church was confiscated for some reason or other, but I understand they moved to the Russian Embassy in Chesham Place. I’m sure you’d find a Russian émigré or two there Sir” [2]

George thanked Cottenham for his advice. It was an absurd idea. Or was it? When the Prime Minister had kissed the King’s hand and left his study, the King called Charlie Phipps into the room. The King’s Private Secretary was quite used to unexpected requests but this one seem more unexpected than most. The King asked Phipps to go along to the Russian Embassy on Sunday afternoon (“One assumes they worship on Sundays like the rest of us”) and to see if he could find an Orthodox Russian who spoke good English and who was “respectable” enough to bring back to the Palace to be introduced to Princess Charlotte Louise before she headed to Brighton. Phipps agreed. And then immediately wondered what constituted a “respectable Russian”.

Chesham Place and the building which once housed the Imperial Russian Embassy in London.

In the meantime, the King had an audience with Sir James Graham. It was quite usual during general election campaigns (which at this time could last as long as three months) for the Sovereign to meet with the Leader of the Opposition at regular intervals. This was entirely practical, as though the monarch would no doubt be familiar with them, Prime Ministers enjoyed spending far more time with the monarch than they do today in a social capacity. It was considered that these meetings helped to put the Leader of the Opposition at his ease; and for those who had once served as Prime Minister and been ousted, there was the cushion of still remaining within the royal inner circle until such a time as it seemed prudent to ditch them entirely from the Buckingham Palace guestlist. George expected Graham to brief him on the Tory election campaign. Or to discuss his ambitions to put right the food crisis or to put down further uprisings in the North of England, or in Wales. But he didn’t.

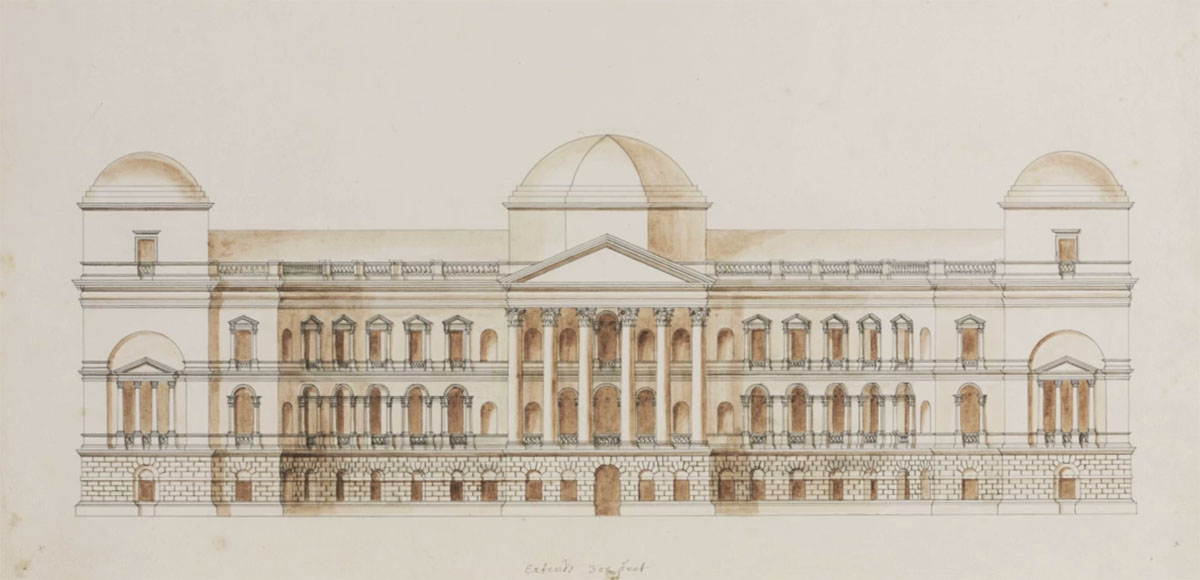

Instead, Graham asked the King if he might be so kind as to introduce Sir James to Decimus Burton. It was not for himself of course; Graham had no vision of building a grand country house or London villa. Rather, he intended to revisit something in the first few days of his premiership (Graham being a great one for counting his chickens before they hatched) which needed urgent resolution. During the Great Thames Flood, the foundations of the new Palace of Westminster (and the scaffold) had been badly damaged. Worryingly, the foundations which had been laid were fashioned from Magnesian Limestone from the Anston quarry of the Duke of Leeds. [3] The stone had been hurriedly quarried and was badly handled. When the water was pumped from the foundation, the limestone foundation appeared to be covered in thick green slime and was badly pockmarked from the debris that had swamped it. Graham believed it prudent to return to the design stage and ask whether Melbourne’s preference was in fact the right choice before the foundations were replaced.

Graham was being a little disingenuous. In fact, he had two reasons for wishing to address the situation at the Palace site. Firstly, there was the spectacle of the thing. Graham would be able to announce in his first few days that it was a new decade and a new political era, something which should be commemorated with a new parliament that wasn’t mired in Gothic brown stone. He also saw an opportunity to slash the budget in light of the Great Thames Flood earning a little public goodwill from Londoners. But his main objective was entirely political. The Tories had disliked the Barry and Pugin design and there were claims of cheating and fraud during the selection process. Here was a chance to kick the Whigs when they were down. Indeed, during a hustings speech, Graham pledged to rebuild the palace of Westminster at a reduced cost "free of Whig corruption". In this, he was referring to the fall out from the “competition” held to find a new design. Of the 97 entrants, 34 complained that Barry and Pugin had cheated.

Their evidence was to be found in the corner of the Barry and Pugin design; both men had signed it. This was quite usual, except the competition rules which regulated the submission of designs made it clear that each entry was to be marked with a pseudonym or symbol which could later be used to identify the architect responsible for the winning design from a list held by the Speaker of the House of Commons. In the view of those who had not been successful, Barry and Pugin had broken this rule and should therefore be disqualified, and their design scrapped. Their petitions to parliament were ignored – Melbourne liked the Barry/Pugin design and that was the design the Royal Commission (comprised mostly of Whigs) plumped for. But the Tories were not so keen. Whilst a handful (such as Sir Robert Peel, a close friend of Barry) were in favour, most objected not so much because of the “victory of the Gothicists” but rather because they felt the process was “crooked and corrupt”. They wanted to re-open the commission.

Graham knew that the first few months of his premiership might not be easy. He needed a distraction. He found one in the design for the new Palace of Westminster. In his defence, it was an urgent matter. Parliament had been without a proper functioning home for 6 years. The budget for the Barry and Pugin design was predicted to spiral beyond the £700,000 allocated and the Great Thames Flood had set the building work backward by an estimated 14 months. But it is more likely that Graham felt a debate on the future look of the new palace of Westminster would catch the imagination of MPs and Peers of all political persuasions, giving him ample time to assemble his Cabinet and fix a list of priorities without every decision being scrutinised too closely in the Commons and Lords. And the Lords would feature very prominently on that list of priorities.

In 1832, Earl Grey had convinced the Duke of Clarence to create 76 new Whig peers to break the political stalemate following the Days of May crisis [4]. Graham might well win a majority in the Commons, but the Whig-heavy Lords would throw each and every bill into the rubbish bin the moment it crossed the despatch box. Graham would have no choice but to ask the King to “balance the Lords”, something which was likely to be controversial and unpopular. It was far better that politicians of both houses of parliament should preoccupied looking elsewhere when the inevitable happened. Sir James had peaked the King’s interest with his mention of Burton. Suddenly their meeting was derailed when George lost focus and brought out the plans for the Regent’s Park redevelopment. “Of course, these will be laid before Cabinet for their approval”, George said, waving a hand over the blueprints.

“But Sir, you do not require Cabinet approval for this project”, Graham replied, quite sincerely.

“No but I should welcome it just the same”, said the King, “I shan’t be accused of being extravagant. When the time comes, if there is opposition in parliament, I want it to be said honestly, truthfully, that my government has faith in these plans and that it has approved the way the project shall be funded”

Naturally, he agreed to put Graham in touch with Decimus Burton to discuss the issue of the new Palace of Westminster. But Sir James was cunning. For as long as his audience with the King remained on what Graham’s priorities would be in his first 100 days in office (if he won the election), there was a risk that they might stray into controversial territory; the Tory approach to the Corn Laws, China, Afghanistan…the House of Lords. It was far better to leave things vague and to distract the King temporarily. Graham was not due to meet the King again until after the general election; when he left Buckingham Palace, the King sang his praises to Charlie Phipps; “He really was very interested in these plans you know Charlie”, he said happily, “I think that shows great vision, what?”

Phipps wisely agreed. Besides, he had more pressing matters to discuss with His Majesty. He had carried out his errand to the Imperial Russian Embassy (not an easy feat) and had returned with a name for the King; a so-called “respectable Russian”. They did not come more respectable than Mother Barbara Shishkina, a Russian-born Orthodox nun who had travelled to England with the hope of founding an Orthodox convent. Unfortunately, she had overestimated the requirement for such an establishment and had since found herself as the housekeeper of the Russian Embassy in Chesham Place. She was happy to remain so because this gave her unrestricted access to the Orthodox Chapel which she found an appropriate place to wait until God gave her another sign. Mother Barbara was renowned at the Embassy for capturing wealthy Russian aristocrats visiting Belgravia and pleading her case in the hope that they might donate generously to her convent fund. Few did. She was somewhat taken aback to be approached by the smart gentleman who explained that he had questions about Russia and the Orthodox faith. At first, she told him to go and speak to a priest but then she noticed his signet ring and tie pin. This was a man of means.

Mother Barbara Shishkina, painted c. 1841/2

On the following Tuesday afternoon, the King invited himself to Marlborough House for tea. Princess Charlotte Louise had yet to formally take up residence there, but she was spending much of her time (distracting herself from the possibility of Sasha’s impending proposal of marriage) by touring the property and seeing which things she might like to change. The first casualty was a vast portrait of her mother which still loomed large from above the fireplace in the dining room. When asked where she would like the portrait to be stored, the Princess replied, “Throw it into the fireplace below for all I care”. Her new Private Secretary, Sir John Reith, thought better of carrying out her orders and sent it to Windsor instead where it was hidden away in a cellar room covered only by a thick dust sheet. The portrait was eventually rediscovered in 1958 and is now on display in the picture gallery at Buckingham Palace.

Princess Charlotte Louise was excited to see her brother, having just received news that the Tsarevich would arrive at Southampton bound for Brighton in just a few days. She would leave London the moment she heard he had docked. Only the King didn’t arrive at Marlborough House that day; Charlie Phipps did. He extended the King’s apologies to the Princess and asked if she might receive the other guests the King had invited to join them regardless of his absence. Somewhat taken aback, the Princess agreed and was even more surprised when two women dressed in black robes and long veils shuffled into her presence. They curtseyed deeply and then rushed forward, dropping to their knees and kissing the Princess’ hands. Charlotte Louise looked startled as Phipps offered an introduction instead of an explanation; “May I present Mother Barbara and Sister Anna from the Imperial Russian Embassy, Ma’am”.

Charlotte Louise was about to get a small glimpse of what her future might hold.

[1] This anomaly was actually addressed during the OTL revisions made in the Succession to the Crown Act 2013. Cottenham is interpreting the Act of Settlement much as it was in recent years; whilst the Act at this point in TTL clearly states that no person who “holds Communion with the See or Church of Rome or [professes] the Popish Religion or shall marry a papist” can be King, it doesn’t stress that the Sovereign must be an Anglican…except it makes it impossible for him not to be. Technically Princess Charlotte Louise could succeed her brother as an Orthodox Christian – but she could not be Crowned. That’s what Cottenham is relying on here in his advice to the King.

[2] In fact, the Greek Orthodox Church at what is now Greek Street was confiscated in 1684 because of a court case in which the manservant of the founding Archbishop (of Samos, Joseph Georgerines) accused him of being “a Popish plotter”. The court upheld the complaint, and the church was handed over to Huguenot refugees from France. Thereafter, the Eastern Orthodox community (both Greek and Russian) worshipped at the Imperial Russian Embassy which in 1840 was still located at Chesham Place in Belgravia.

[3] This was actually a concern in the OTL, but it was overlooked. By 1849, there was a great deal of “I told you so” when much of the stonework showed signs of extreme weather damage. We’ve got an excuse to ramp this up here with the aftermath of the Great Thames Flood. It’s also true that in the OTL, many Tories opposed the new palace design because they saw it as a convenient excuse to have a bash at Lord Melbourne. But Melbourne stayed in place until 1841 in the OTL and therefore, their complaints were ignored. Not so here.

[4] See:

https://www.alternatehistory.com/fo...-british-monarchy.514810/page-9#post-22599916