King George V

Part Two, Chapter Three: Russell’s Gamble

The New Year of 1839 was celebrated with additional excess at Buckingham Palace. The birth of Princess Marie Louise had not only brought great personal joy to the King and Queen, but the British people too had combined their usual Christmas celebrations with a spontaneous (and surprising) outpouring of festivities to celebrate the birth of the Princess Royal. All over England, churches bent to public demand for thanksgiving services for the safe delivery of the King’s daughter and in Norwich, the Lord Mayor proudly boasted that his city would be the first to formally honour the Princess by renaming Gentleman’s Walk

Princess Royal Road. These celebrations perhaps confirm the rise of what diarist Charles Greville referred to as “the new royalism”. So popular were the King and Queen (and their new daughter) that the London Times introduced a royalty supplement which for the first time printed the Court Circular [1] in addition to articles and engravings of both British and foreign royalty. Known as “The Royal Digest”, this became so popular (especially among women) that some shopkeepers removed the digest and sold it separately for an inflated price. It was reported that one retailer had sold a copy of the digest for as much as £2 when every other copy had been sold and a woman in Bridgewater outbid her neighbours to ensure her collection of the Digest was complete.

At the Palace, the Queen made appointments to the Royal Nursery, the first reorganisation of the “junior household” since the childhood of King George V. On the advice of Princess Augusta, the Queen had approached Madame Fillon, the former governess of Princess Charlotte Louise and Princess Victoria of the Netherlands, to come out of retirement and become Governess and Chief Superintendent of the Royal Nursery. Affectionately known as ‘Nolliflop’, Madame Fillon was now in her early 80s but the previous generation of royal children had loved her so much that she had been given a grace and favour cottage on the Windsor estate and was never too far from the Royal Family. Fillon was delighted to return to royal service but her advanced age meant that her role was very much that of a general supervisor rather than as a maid of all work as she had previously been. The Duchess of Sutherland recommended Lady Maria Jocelyn, the younger sister of the Countess of Gainsborough (one of the Queen’s ladies of the bedchamber) to be appointed as Sub Governess and it was Maria (known to the Royal Family as Milla) who would come to rule the royal nursery with a rod of iron.

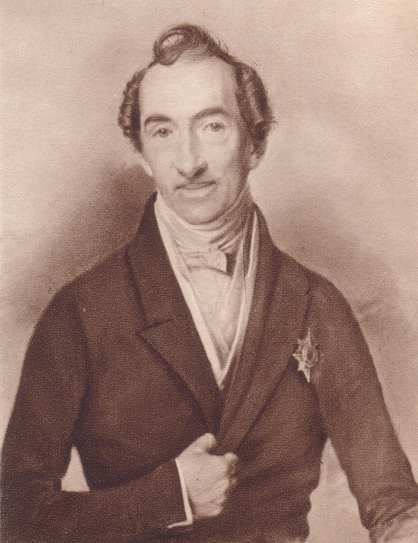

Lady Maria Jocelyn.

In addition to the Governess and Sub-Governess, the Royal Nursery had a permanent staff of twelve. These included Mrs Hannah Wadley, the wife of a dairy farmer from Windsor, who served as wet nurse to the Princess Royal, four permanent nursery nurses, three nursery maids, a monthly nursery physician and a nursery “tweenie” who served as a general dogsbody to all who came before her in the pecking order. There were also two pages to fetch and carry. The Royal Nursery operated as its own little kingdom within the Royal Household and Governess Fillon (raised to the rank of Baroness in the peerage of Hanover by the King to mark her appointment and give her social superiority over Lady Maria Jocelyn) laid down strict rules which were never to be broken. Until her christening, the Princess was to be known as ‘Baby’. After that time, every member of the nursery staff was to refer to the child as ‘Her Royal Highness’ or ‘The Princess Royal’. Only Baroness Fillon and Lady Maria were allowed to call her

Missy, the nickname given to the baby by her mother in the days before her christening. Even then, they would not dare do so in the presence of the King and Queen. Everything from meals to baths to the changing of linens was so finely tuned that the King remarked he should have made Nolliflop a General in the British Army rather than a Baroness. [2]

The British Army was foremost in the King’s mind that January. News came from Punjab in the first week of the New Year that that the ‘Great Army of the Indus’ (comprised of 21,000 British and Indian troops under the command of Lord Keane) had set out for the Bolan Pass some 75 miles from the Afghan border. The British press were suitably jingoistic and rather than focus on the anti-war sentiment that was now dominating the Afghanistan debate, they happily reported that the so-called Great Army was to be joined by 38,000 camp followers and 30,000 camels. One regiment took a pack of foxhounds whilst another took two camels to carry a supply of cigarettes. There were reports of special orders of claret and preserved game being shipped to the senior officers who saw no reason why they should do without their home comforts and one newspaper even suggested (perhaps inaccurately) that a nameless Major had taken six servants with him to carry his collection of walking sticks.

George Eden, the author of the Simla Manifesto which had prompted Palmerston’s decision to commit British troops to war in Afghanistan, wrote a letter to be published in the newspapers which promised “an efficient campaign” which was bound to deliver “peace and stability not only in Afghanistan but throughout British India”. The King was not so sure. In recent weeks, he had entertained the Duke of Wellington and was convinced that Melbourne and Palmerston were about to lead the British Army into a disastrous campaign that may have serious consequences not just in Afghanistan but in India too. Any loss for the British could well be interpreted as weakness and at a time when the fear of uprisings and rebellions against British rule in India were a genuine concern in London, Wellington believed the Prime Minister and the Foreign Secretary to have acted on the worst possible advice.

But the King could not share such views with his Prime Minister, or with Lord Palmerston. The Duke of Wellington was a close friend to the Royal Family and Lord Melbourne did not resent that fact. When asked if he thought it suitable for a former Tory Prime Minister to stand as a godparent to the Princess Royal, Melbourne replied, “He is more than that Sir. He is the hero of Waterloo and truly deserving of such an honour”. Even so, Melbourne was unlikely to be as generous to Wellington if the King urged caution in Afghanistan based on the Duke’s advice. George was learning all too soon the restrictions that came with his position, yet his interest and commitment to the British Army pushed him to intervene as best he could. He opted to do so via dinner party diplomacy. In the third week of January, the King invited General Sir George Scovell from the Royal Military College at Sandhurst to dine at Buckingham Palace. This “celebration of old soldiers” also included the Duke of Wellington, General Sir Colin Halkett, Lieutenant General Sir John Hope and General Sir Thomas Bradford. These great military veterans came together with a vast wealth of experience from Waterloo to Bombay and the Iberian Peninsula and it was considered quite usual for such distinguished guests to be honoured by the King with a private dinner party.

The Duke of Wellington.

King George however, had an ulterior motive. He wanted advice from the very best military minds and after the meal was concluded and port and brandy were served, the King openly asked; “Well Gentlemen, what say you about this Afghan business?”. For three hours, the great military veterans gave their frank and honest assessments. Halkett took over the dining room using cruets and decanters to show how he would approach such a campaign, whilst Bradford called the entire thing “Melbourne’s folly” and predicted nothing but disaster. Sir John Hope took a more balanced view. In his opinion, if the British made substantial progress through the Bolan Pass and could fight off raiders from the Baloch tribal forces, they stood a good chance of flushing Dost Mohammed Khan into exile and might consider the campaign to have been a success. But he urged caution too. In his view, it was unlikely that Shah Shuja could maintain order and he would need significant British support to preserve his authority. This was likely to cost the British a small fortune, and besides the financial burden, it would drain the British forces in India. It was not so much the Afghan campaign which concerned Hope, more so it was the aftermath. The King agreed.

In doing so, George was aligning himself with the Tory position on the Anglo-Afghan War. But he was also putting himself firmly in the same court as Lord John Russell. Russell had had many weeks to consider his next step and encouraged by his supporters and colleagues from the Russell Group, he was being urged to challenge Melbourne at the earliest opportunity. The Tories had caught wind of the quarrel between Melbourne and Russell and when parliament returned after the Christmas recess, the new Leader of the Opposition, Sir James Graham, made a concerted effort to portray the Prime Minister and his Foreign Secretary as lacking the confidence of the wider Whig party for what he dubbed “Palmerston’s misadventure”. The Unionist benches agreed with Graham. They smelled blood too and Henry Farmer wasted little time in branding the Prime Minister “so disinterested in foreign policy that he allows the Foreign Secretary to engage British troops in a misguided mission to prevent catastrophies which only exist in the mind of the Right Honourable Gentleman and have little bearing in reality”. The Tories and the Unionists urged Melbourne to reconsider Palmerston’s position as Foreign Secretary. Melbourne stated that he had every confidence in Palmerston and that the government was committed to its campaign in Afghanistan “for the peace, security and prolonged stability of the Empire”.

As Melbourne sat down, he was passed a note from the Leader of the House of Commons. It was his resignation. To a stunned silence, Lord Russell stood and delivered a brutal political (and very personal) attack against the Prime Minister which was nicknamed “Russell’s Gamble”. British troops were now committed to the campaign, Russell accepted, but it was a commitment made without the full backing of the cabinet. As Secretary of State for War and the Colonies, Russell revealed that he had known nothing of the plan to invade Afghanistan and depose Dost Mohammed Khan until Melbourne had agreed the path forward with Lord Palmerston. In this, Melbourne had shown a lack of confidence in Russell “which I regret to say I must tell the House that I share in the Right Honourable Gentleman”. He went on to describe the Whigs as a family in which disagreements were to be expected as in any other family; "Yet in our household, there are two members joined perhaps closer than most by their association away from this place". Melbourne grimaced. Some Whigs booed. Russell was clearly alluding to Melbourne's sister with whom Palmerston had long been having an affair and now wished to marry. Many senior party grandees felt this a step too far and there were cries of "Bad form man, sit down!".

The remainder of Russell’s speech was nothing less than a personal manifesto. He chided Melbourne for failing to address the economic woes of the United Kingdom whilst allowing for expensive and costly wars abroad. He berated him for failing to make the most of the Whig majority and redressing the widening gap between rich and poor. “But moreover”, Russell concluded, “The Prime Minister has failed to consider that those of us who sit on these benches owe our allegiance to the Crown, to the United Kingdom and to its people first and foremost. Where we see that the interests of the British people are secondary to the personal irrationalities of those in a position of authority, we must ask ourselves if the time has finally come for those who take advantage of old friendships in assuming unquestioning loyalty, to make way for a Prime Minister who shall not be brow beaten into acts of war he knows to be flawed and foolish”. The reaction in the House was electric. The Tories and Unionists jumped to their feet and waved their order papers, cheering in agreement. But worryingly for Lord Melbourne, there were significant “hear hears” from his own benches.

Lord John Russell.

In tying Melbourne and Palmerston together as the architects of failure, Russell was attempting to set a trap for the Prime Minister and his Foreign Secretary. If the Afghan campaign was proven to be a disaster, both Melbourne and Palmerston would have to pay the political price and step down. Palmerston was one of Russell’s most obvious rivals for the post of Prime Minister and now, all Lord John had to do was wait. If his predictions came true and the Afghan campaign ended in failure, the door to Downing Street would undoubtedly swing open in his favour. Melbourne was furious at Russell’s disloyalty and on the journey back to Number 10, he remarked; “That was the most disgusting display of betrayal I have ever witnessed, even by the standards of that cesspit of a place”. That evening, Lord Melbourne was to face his weekly audience with the King. He thought it best not to mention Russell’s resignation speech but naturally word travelled fast, and the King was well aware of what had transpired at Westminster.

The King had made up his mind to casually refer to Hope’s cautionary advice from the previous evening in a round about way but when Melbourne arrived, he found him unexpectedly buoyant. Reports from the front line suggested that there had been fewer raids in the early days of the crossing of the Bolan Pass than expected and General Keane’s prediction was “a smooth and mostly unchallenged crossing into Ghazni, from where Kabul surely must lay in easy reach”.

“The news is therefore good Your Majesty”, Melbourne smiled, sipping his glass of sherry.

“Indeed”, the King replied, “Though might it not be better to say the news is conditionally good Prime Minister? There is a possibility that things will not progress as easily as General Keane suggests?”

Melbourne put down his glass and nodded at the King.

“Your caution does you credit Your Majesty. But I wish to assure you that General Keane is not a man prone to exaggeration”, he began, “The government has every faith in him and in his report and-“

The King’s nerves got the better of him. For the first time in his reign, he would have express disagreement with his Prime Minister and it was not a prospect he relished, however well-rehearsed or well researched his objections.

“But Prime Minister, does

every member of the government have faith in General Keane? Or in the campaign itself?”, he replied, “I have to tell you that I do have concerns-”

“Of course you do Your Majesty”, Melbourne smiled again, “We all have concerns in a time of war. But the naysayers you have no doubt heard from are ill-informed, they will soon see the fruits of our labours in Afghanistan and I expect very good news from Ghazni in the coming months which will soon silence our critics”

“You mean Lord Russell?”. The King’s words hung in the air for a while. Melbourne appeared uneasy.

“Lord John Russell has long held a different view to the Foreign Secretary on such matters”, he said calmly, “I will confess I was surprised by his speech today. I might go further and say I was a little hurt. I had not thought he should be so brazen in his ambitions and it is true you may find others in my party who share his view. But we cannot let one dissenter deter us from our course Sir. When I see Your Majesty again, I have every confidence that you shall have glowing reports of our triumphs in Afghanistan from General Keane and those opposed to our actions shall have their fair share of humble pie to eat for supper.”

Melbourne laughed. The King gave a weak smile. He wished to counsel Melbourne on the aftermath of the campaign. In his mind, he knew the right course of action, but he was anxious too that he would overstep the bounds of his constitutional role. There was another issue too. Melbourne was a great statesman and three times the King’s age. He did not wish to add insult to injury by lecturing such a man when he had already been put through the ringer that afternoon by those he had once trusted. But ‘confidence’ was a word the King could not easily overlook. The King did not have confidence in his Prime Minister in this matter, neither it appeared did a significant majority of his own party. That could lead to a serious constitutional crisis. For the time being, George agreed to “wait and see” as Melbourne suggested. If the news from Afghanistan was as positive as Melbourne promised it would be, the King would reassess his position. Equally, if the news was not as the Prime Minister had predicted, the King would feel emboldened in his position and would take further advice on whether or not he should seek Melbourne's resignation - or even dismiss him from office.

Whilst Lord Melbourne left the palace that evening feeling that he had eased troubled waters; he was not entirely convinced himself that everything he had told His Majesty was entirely true. He had his own reservations about just how widely Lord Russell's sentiments would carry and he urgently needed some word of victory from Afghanistan to silence his critics and preserve his premiership. Upon his return to Downing Street, there was no such word. Instead, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Thomas Spring Rice, had asked for an urgent meeting. Russell’s intervention in parliament had lit the touch paper and now, those who had previously remained silent out of loyalty to Melbourne (no doubt in the hope of promotion or other favours), had begun to express more general concerns to the Chancellor that all was not as it should be.

Rice himself had warned that Britain could ill-afford a drawn-out campaign in Afghanistan but he was ignored. With no sign that the Whig economic reforms had gone far enough to prevent a financial crisis, the situation could quickly deteriorate if the war did not go the way Melbourne and Palmerston were certain it would. Again, Melbourne reassured his Chancellor that General Keane promised a quick victory, but Rice was unconvinced. Earlier that evening, Alexander Bannerman, the Whig MP for Aberdeen, a staunch supporter of Lord John Russell who was acting as a recruitment officer for dissenters in the party, had called on the Chancellor. He was clearly seeking new allies for a Russell challenge and though Rice was careful not to commit himself either way, he could not deny that Russell's speech had set a challenge for the Prime Minister which Rice had concerns his old friend and colleague might not win.

The Duke of Cambridge.

As the political establishment waited on tenterhooks for news from Afghanistan, the Duke of Cambridge requested an audience with his nephew. He too had been in communication with senior military personnel who were greatly concerned about the ongoing situation abroad but this was not primarily the reason for his visit. Upon relinquishing his role as regent, the Duke had been promised that if he waited until after the coronation, the King would put into motion the recall of the Duke of Sussex from Hanover and reinstate the Duke of Cambridge as Viceroy. The Cambridges now wished to make arrangements for their return to Herrenhausen if the King was still willing. But George was far too preoccupied with his recent meeting with the Prime Minister. Before his uncle had a chance to talk, the King jumped at the opportunity to seek his advice. Had he been too harsh? Had he not been harsh enough? Cambridge praised the King for his measured response and agreed that he should do the same as other interest parties and wait for news from the front.

“I am grateful Uncle”, the King smiled, patting his uncle on the back, “Really, we should not know what to do without you”.

The Duke of Cambridge hadn’t the heart to remind his nephew that his intention was to leave Britain and return to Germany. Instead, he turned to family matters. His wife Augusta had received a letter from the Dowager Duchess of Clarence on Malta that Princess Charlotte Louise had departed to return to England and was “fully recovered from the past year's unhappiness”. The Dowager Duchess wrote that the Princess was “bright and gay with a glow in her cheeks, which I dare to suggest may have been put there by letters from the Tsarevich”. The King was suddenly not smiling. He had only allowed the Tsarevich to correspond with his sister out of politeness. He was still hugely protective of Charlotte Louise and he instinctively felt the need to reject anything that might put her in arms way once again. That said, he did not wish to follow the example of his mother either.

The King asked the Duke of Cambridge to welcome the Princess home from Southampton on his behalf and to bring her to Buckingham Palace as soon as possible, where the King intended she should live now that she was over her disappointments and prepared once more to be seen in public. Cambridge agreed but felt the need to voice a concern both he and his wife had felt for some time. Whilst it was only natural that His Majesty should be protective of his sister and wish her to be safe and happy, she would soon be 18 years old. Though she was unmarried, a precedent had been set during the reign of King George III that his daughters were given their own households when they came of age and the Duke advised the King that he might begin to give the matter some thought. "No no", the King replied, "I know Lottie would much rather stay here with us".

“Partings will come Georgie”, the Duke said softly, “But it is how we bear those partings which defines our character and gives us the greater chance of happiness in spite of them. One day too, I shall no longer be here but I know that my advice and help will continue to serve you well. That is my hope, at least”.

George smiled. He knew his uncle was keen to return to Hanover and he intended to honour his promise. Just not so soon.

“We are a family”, the King replied beaming, “If I can preserve nothing else in my lifetime Uncle, I am determined to preserve that”. The loss of his father and younger brother, not to mention the separation from his mother, had left the King hungry for the love of a large family. This would come to define his personality perhaps more than anything else and it was around this time that the first glimpses of that motivation could be clearly seen by those closest to him. Following the Queen’s recovery from childbirth and the difficulties it had brought for mother and baby, the King had become almost obsessive, frequently visiting the royal nursery two or three times a day and demanding twice daily reports on the Queen’s activities and health. This now extended to his sister as she returned from England and whilst those affected did not complain (they knew it to be well-intentioned), it is worth noting that even though George was not averse to change, he had also come to dislike the idea of those he held most dear being too far away. In the future, he would often allow himself to lead with this fear of separation when asked to confront family difficulties and if he had a major flaw in his character, it was perhaps that his heart could all too easily rule his head.

In April 1839, news finally came from Afghanistan that the British forces had successfully crossed the Balon Pass. The rough terrain had proved no match for the troops led by General Keane and they had marched on to secure the city of Quetta with a view to progressing to Kabul in the coming weeks. From Kandahar, General Keane wrote; “We have taken Karachi and the Grand Army we have assembled is a much-feared fighting force which the tribesmen seem unwilling to tackle, and which makes for a quick advance. I predict we shall make decisive victories by June or July at the very latest and I can also report that we have made contacts with a camp of deserters of Mohammed Khan’s fighters who tell us that morale among our enemies is low and that the ex-Emir himself is to take flight to Bukhara ahead of our advance”. Melbourne breathed a huge sigh of relief. He proudly relayed the report to the King, to the Cabinet and to Parliament. Russell’s Gamble, it appeared, had not paid off for the Prime Minister's would-be successor. But how long this would hold to be true was already being debated in the drawing rooms of Westminster. As Melbourne revelled in this reprieve, those around him could not help but feel he was far from out of the woods.

[1] George III established the Court Circular to correct false reports about the whereabouts of the Royal Family, but it was only carried in the London Gazette until the Times began to print it in the 1840s. Here the Times adopts it a little earlier to reflect the rise in popularity of the Royal Family.

[2] This is modelled on the way the royal nursery operated in the 1840s/50s which is detailed in the brilliant book

The Victorian Royal Nursery by Mariusz Misztal.

With regards to Madame Fillon’s elevation, this was not automatic for the Head Nurse of the Royal Nursery though some regard the elevation of Baroness Lehzen as an example that it was a title owed to the incumbent. In the OTL, George IV only raised Louise Lehzen to the rank of a Baroness because he did not wish his niece to be “surrounded by commoners”. Here, the title reflects a reward for long service but also to solve a precedence issue and would not be automatic for Fillon's successors.