Anahuac Triunfante: A more united and successful Mexico from Colony to Enduring Republic TL

Part 6: The Next Generation

Chapter 3: El Trinio Politico, Mexico 1848-1857

After the North American War Mexico began the process of reinventing itself. A major blow to the old ways was the upset of the 1849 elections in which the traditionalists saw themselves lose decisively. President Anastasio Bustamante’s hold over power was severely compromised by his agreement with the constitutionalists whose support he needed to win the war and as a result was unable to rig the elections after a series of crises engulfed the nation culminating with a vicious rumor of treason. The period between the last year of the North American War and the outbreak of the War of the Reform came to be known as “El Trinio de Partidos”[1] meaning The Three Parties as three different political parties held power, The Traditionalist Pary, Liberal Party, and the new Constitutionalist Party. On paper that might appear to be a sign of a functioning democracy, but in reality each transition drew Mexico closer to the War of the Reform in 1857.

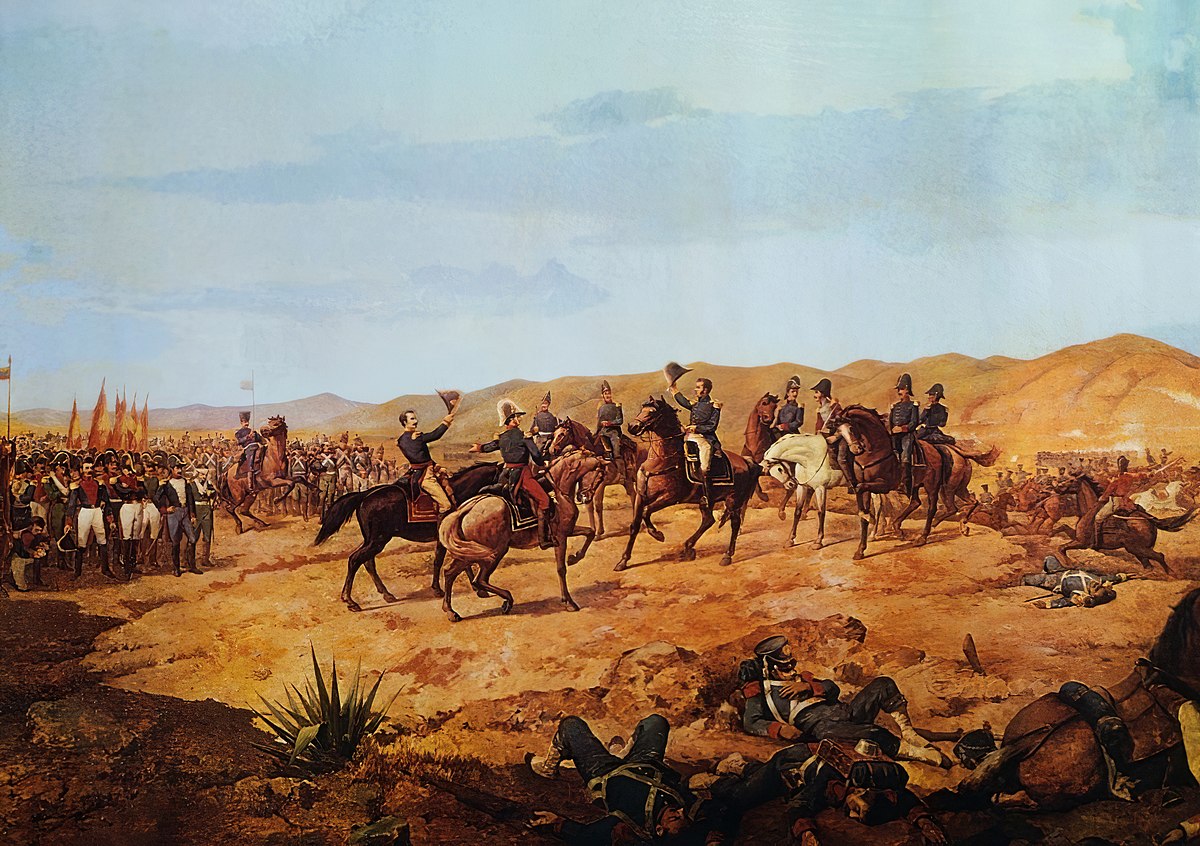

Chan Santa Cruz

The carnage of the Caste War [a]

Since before the North American War periodic outbreaks of violence among the Mayan populations in the Yucatan peninsula. and conflicts erupted in the Yucatan peninsula over land rights and abuses Mayans suffered under the criollo land owning elites. Before the war started, many Mayans were promised land grants in the northern frontier only to never arrive but fund themselves living in debt peonage in Central Mexico. Once the war began, an increasing number of Mayans caught on to the sham after various nefarious individuals continued to promise passage to the war-torn frontier. As a result, the criollo elite resorted to naked land grabs and forced labor through various underhanded schemes including predatory loans, fabricated claims, scams and land confiscation at the instigation of trumped up criminal charges which often times resulted in forced labor to “work” off their sentences.

Tensions and minor conflicts were in effect two years before the North American war and entire cities and towns in eastern Yucatan began ignoring Merida, and even Mexico City by the time the war broke out with the United States. Uprising and wholesale revolts overthrew local governments in several towns and villages. Mayan rebels had established a new nation called “Chan Santa Cruz” after its main city providing for even a new syncretic religion between traditional Mayan beliefs and Catholicism known as the Mayan Church.

At first, the rise of Chan Santa Cruz was treated as yet another spat of violence. Merida sent a small militia force to arrest the main leaders of Chan Santa Cruz, only to be chased away beginning the Casta conflict, it would receive no aid from the Federal government as it was too busy fighting the Americans. By 1848, Chan Santa Cruz had developed its own constitution and established territorial control over eastern Yucatan and began attempts to take over southern Yucatan as far as the Gulf port city of Campeche. José Crescencio Poot raised an army made up of a group of rebels called the “cruzoob” and marched towards Merida with the goal of apprehending the Yucatan leadership and forcing them to “respect Chan Santa Cruz sovereignty”. With the majority of the state’s forces still in Central Mexico, Merida was unable to sally forth and meet the armed force in the field. Bustamante had to send yet a force of war weary veterans to assist Yucatan state forces and suppress the rebellion.

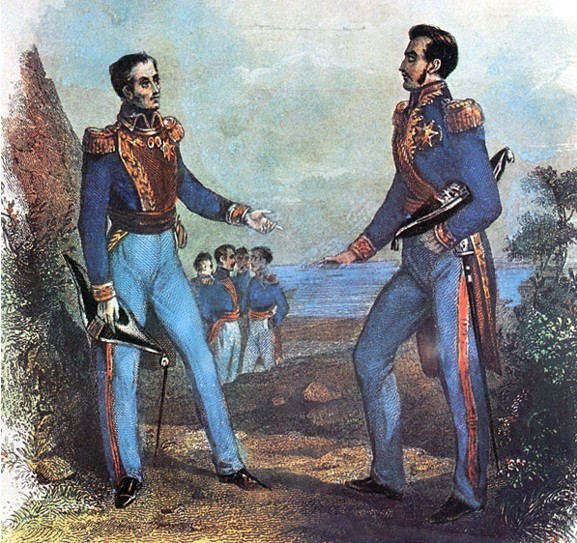

Several battles took place throughout the period between November 1848 and June 1849, some of which involved defeat of Mexican forces. It wasn’t until the intervention of Benito Juarez and the Constitutionalists that a ceasefire was called. Juarez was chosen to mediate a peace between the Yucatan government and the Mayan rebels mainly due to his Zapotec lineage, a move that was met with some measure of success as the Mayan rebels were willing to listen to a Zapotec as opposed to yet another criollo or even a mestizo (mestizos were seen as blind followers who accepted criollo abuse and thus not trusted by some of the more radical elements of the rebels even though they largely sided with the rebels). Benito Juarez met up with the Chan Santa Cruz representative, Florentino Chan and the Yucatan governor Domingo Barret Rodriguez.

During the negotiations the Mexican public received shocking news. Juarez, in a fit of opportunism, made sure to publicize as much as he could in the negotiations and his constitutionalist allies made sure to have as many men as possible read his reports in front of as many crowds of Mexicans and inside as many churches as they could get away with. The nation was shocked to hear that the Caste system lived on in the Yucatan, though ironically it really wasn’t that much different in the rest of the nation but only that it was more pronounced in the peninsula given that the Yucatan government had always been given much more autonomy than any other state. While the full extent of the abuses since independence weren’t widely known, the more recent abuses of land grabbing and forced labor were. The revelations not only hurt Bustamante, but the entire traditionalist party for being seen as being permissive if not down right supportive of the old colonial system, it certainly didn’t help that that party was rife with colonial romanticism.

Juarez managed to convince Chan that the best move was to remain part of Mexico and offered Chan Santa Cruz statehood. The Yucatan government would accept the loss of its eastern territory in exchange for retaining its autonomy. Juarez had threatened Barret with giving the Chan Santa Cruz government control of the entire peninsula as leverage. Bustamante had reluctantly agreed to back up Juarez’s threats as he found himself under pressure after seeing an exodus from his party and the turn of public perception of his presidency. Constitutionalists had spread rumors that the cause of the North American War was not the skirmish near the red river, but rather Bustamante’s centralist plot to be named viceroy of a reinstituted Viceroyalty of New Spain. The romanticism with which many traditionalists viewed the days of the Viceroyalty was well known and lent credibility to the rumors which are unanimously rejected by virtually all historians. The argument went that since this would mean that Spain regains control of an American nation, the United States Monroe doctrine was triggered to prevent such a treasonous plot from reaching fruition. The blatant open practices of the Caste system in the Yucatan being allowed to be carried out by Bustamante lent credence to the rumors as well as the continued desire among party members to have a European Monarch rule over Mexico as a monarchy.

Mexico in 1855 including the newly formed states of Chan Santa Cruz and Alta California with the Arizona and Deseret territories[.b]

(My map making skills are...limited)

In June 17th, 1849, Chan Santa Cruz became the newest state of the republic [2] and the cruzoob army was reorganized into a state militia. The continued existence of the new Mayan religion led to the relaxing of Mexico’s religious requirement. In the law that was passed by the congress to ratify the treaty the proscription of non-Catholic beliefs was amended to allow for the continued existence of the Mayan church. The new law stipulated that religions “friendly” to the Catholic Church which recognized the ecclesiastical authority of Pope and belief in God and the bible would be tolerated in limited circumstances. Chan Santa Cruz was forced to include its recognition of the Catholic Church as being the “one true mother church”. This sparked controversy over the treaty, but it still managed to be ratified effectively beginning the path towards official de jure religious tolerance in Mexico, a long-sought goal of its liberal factions.

The Indian Wars

The conflict with Chan Santa Cruz was part of a larger series of conflicts known as “The Indian Wars” By the end of 1848, Comanche and Yaqui resentment towards Mexico began to boil over into open conflict. Anastasio Torrejon’s deal with the Comanche to provide for support in the North American war was not honored by Bustamante nor the congress. As a result, three raids against communities in New Mexico and Texas were launched by the Comanche culminating in a fourth larger raid in Chihuahua in January 12th 1849. A calvary regiment stationed in Texas led by Archuleta was sent to hunt down the Comanche camps while Bustamante secured funding to build new Presidios in Comanche territory designed to impede their movements. Juan Bautista Vigil y Aralid, the appointed governor of New Mexico, also began recruiting militiamen from as far south as Chihuahua and worked with the Texan provisional state assembly to establish bounties for Comanche scalps. He even went as far as offering cover for American bounty hunters, mainly former soldiers from the war during the months of February and March. Inadvertently, many of the bounty hunters didn’t care to differentiate the Comanche from their Navajo and Apache neighbors causing a full-blown conflict that led several battles with militias and Archuleta’s calvary.

The violence even reached the Pueblo as the more unscrupulous bounty hunters began attacking them. Pueblo Indians had been on the path to integration within Mexican society much in the same way as many native peoples in Central Mexico. They were by and large considered “civilized” unlike their Navajo-Apache neighbors, and certainly opposite to the Comanche. The situation alarmed many Mexicans in the region and began demanding further federal support to restore order. Vigil y Aralid scapegoated Bustamante’s administration complaining to Bustamante’s political enemies and some of his less loyal allies drawing parallels with the situation in the Yucatan peninsula.

In the state of Sonora, the local indigenous peoples had been held in check by being awarded a level of autonomy and participation in the political structure of the state, that was ended during Bustamante’s administration. Much like in the Yucatan, violence erupted. By The different groups coalesced into a confederation led by the Yaquis under Juan Banderas who raised an army in revolt against the Sonoran government. With the bulk of Mexico’s forces dealing with the War, Sonora was largely abandoned by Mexico leading a flight of Mexicans from the state. The plight of Sonora did not become well known until the end of the North American War which served as a major blow to Bustamante’s popularity when paired up to the other conflicts. An entire division of war weary veterans was sent to restore order in Sonora by February 1849.

The Mormon Refugees

Mormon Refugees arriving to El Gran Lago Salado in 1849

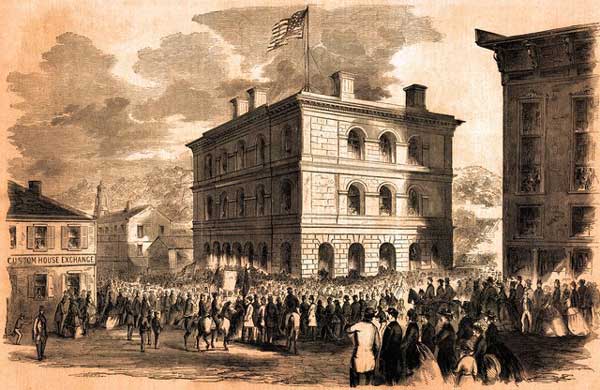

During the elections of 1849, José Joaquín de Herrera was voted into the presidency under the Liberal Party thanks to the flight of moderates from the traditionalists establishing the Liberal party as a centrist party. Herrera promised to bring stability to the nation “mismanaged by the traditionalist Brutamante” using a play in words with Bustamante’s name to make it more like Spanish word for “brute”. The elections also saw new faces in the Congress, including Mayan representatives from Chan Santa Cruz.

Fleeing religious intolerance and violence, Mormons had settled in the unorganized territories of the US during the North American War. During the occupation, Ampudia recognized the Mormons as dissidents to the protestant rulers of the US and afforded them some privileges in exchange for their support. When the war ended, Brigham Young asked Ampudia for permission to scout the region around El Gran Lago Salado. [3] Several Mormons were allowed to settle as they fled continued prosecution which only increased due to Young’s relationship with Ampudia. President Bustamante flatly refused to allow the Mormons to settle and was about to send a force to deport them when the Navajo and Apache declared war.

In July 6th 1849, once the official news of the gold findings in Alta California reached the US, the first of the Filibusters organized with the intention of instigating a rebellion there. William Walker led a force of North American War veterans resentful at the loss across modern day Deseret. Walker’s force of 300 men was stopped by several dozen Mormons who had already settled the area and began chasing away American pioneers who were making their way west to the gold mines. The resulting battle led to their massacre, but managed to dissuade many of Walker’s men who had taken heavy casualties from continuing forcing him to return to the US. News of this reached Mexico City where President Herrera declared the Church of Later Day Saints a “Catholic Friendly Religion” and offered them legal status in the Gran Lago Salado region as long as they promised not to proselytize Mexicans. Brighman Young was all too happy to oblige and had agreed to begin adopting Spanish as his own language. Within the year over 20,000 Mormons settled the area. An additional 15,000 Mormons had immigrated to other places in Mexico including Texas, New Mexico, Veracruz, and Alta California taking advantage of the legal status of the LDS church by late 1850. The LDS church and the Mayan Church were also joined by the Anglican Church (who had de facto legal status) as the three legal non-Catholic religions in Mexico. This, of course caused many clergymen in Mexico to despise Herrera and the Liberal Party, but with the defeat of the traditionalist party and the fact that the newly formed Constitutionalist Party represented an even more liberal mindset they were left with few major political allies in the government. Reactionaries and the church had decided to bide their time.

The Alta Californian Gold Rush

San Francisco Bay during the Gold Rush hosted traffic from ports from Valparaiso Chile to Mazatlan Sinaloa and Acapulco Cuatehmoc and East Asia. [c]

In 1850, Herrera began a project to expand the railroads in central Mexico and begin construction of a railroad line connecting Guadalajara with Mazatlán and La Paz with the San Francisco Bay in response to increased transitory migration through Mexico brought on by immigrants seeking their riches in Alta California. A secondary route from Galvez bay through Santa Fe and across the desert to San Diego was also mapped out for the construction of a railroad. Irish-Americans began arriving in mass to Texas and the port of Veracruz bringing with them their money they had saved up, money they used to buy goods and food along the way representing a new source of wealth for Northern and Central Mexicans.

To help fund the new railroads, Herrera struck deals with Mexico’s wartime ally, the British, to attract foreign investment. Still stale from the war, American investors were at first reluctant to join in on the action for fear of being seen as “unamerican” but by the end of the year they began financing American Catholic and Mormon trips to Alta California under the guise of getting rid of the “undesirable elements of society”. Not all gold hunger prospectors were Catholic nor Mormon. Many non-Irish/non-Catholic Americans managed to sneak and fake their way across the travel routes. Many would legally change their names to Irish names and fake an Irish accent to try to pass off as Irish, a nationality that was most favored by Mexicans.

An entire German-American protestant family, for example, had their name legally changed from “Smith” to “Smythe” and spent several weeks learning how to mimic the Irish accent before setting off to Texas to begin their journey to Alta California. Mexican officials quickly caught on and began to test Americans by trying to coax out their natural accent or ask them trick questions in regards to Mormon or Catholic beliefs. In May of 1850, Herrera managed to push through the legal recognition of the Church of England, a much easier move than recognizing the LDS church or the Mayan church given that North American War propaganda painted the Anglican faith as a “Catholic lite church destined to reunite with the Holy Mother Church”. With now having De Jure legality, many American Protestants began converting to the Church of England as a way to help gain passage to Alta California, however their distinct lack of a British accent or Canadian papers quickly resulted in their denial.

Alta California’s population nearly doubled from 1847 to 1851 to around 100,000. Herrera had also provided land grants to hundreds of central Mexican families to move to the territory to help maintain its “Mexicanness”. German Lutherans began pushing for state recognition along similar lines as that of the Anglicans, many simply began claiming to be Anglicans or converting, their German accents helped convince officials that they weren’t Americans.

Not all immigrants settled down in Alta California. Many of them found new homes in Texas, New Mexico, Veracruz, Puebla, Mexico State, Michoacán, Jalisco, Sinaloa (which was formed from the southern half of Sonora) and Baja California. Afro Cubans and freed African Americans also joined in the migration to Alta California. The arrival of East Asian immigrants also added to this mix, although they were met with fierce resistance and racism more so than other groups outside of Anglo-Saxon Americans and maybe black migrants.

Alta California became one of the most diverse regions in the Americas representing an assortment of nationalities from East Asia to Europe to the Americas including indigenous peoples such as Purepecha, Zapotec, Nahuatl groups and more local groups such as Yuma. Mestizaje (the race mixing Mexicans had become accustomed to) was a culture shock to many European and American Immigrants. Ideally it would be a light skinned man marrying a darker woman, but the reverse also happened. Criollos, indigenous Californians, and Mestizos together still made up a little over a third the population with the arrival of indigenous Mexicans from central Mexico bumping up native population to just about half.

The Land of Oportunidad.

Irish Immigrants on a ship heading to Veracruz in 1848 [e]

With the influx of foreign investment, immigration, and new sources of revenue from the gold rush, Mexico was poised for new growth and development. Herrera capitalized on this with his expansion of the railroads. By 1852 he managed to get some investors from the United States as well as investment from France in addition to expansion of British companies. Herrera’s finance secretary, Manuel Piña y Cuevas, established a new central bank early on in 1850 which began financing farm equipment for the farmers of Central Mexico, most of which was imported, to expand produce and dairy farming. Many families were able to borrow money to transition from subsistence farming to commercial farming by selling new surpluses along the travel routes to migrants heading to Alta California and the growing urban centers. Piña y Cuevas also increased trade duties and established a luxury tax and a property tax for larger land owners sending them back into the hands of the traditionalists who promised a return to better days.

Making use of the new National Bank, several industrialists banded together to form a railroad company, Ferrocarril Mexicano, as the main domestic railroad company often using foreign contractors to make up for the short coming of expertise. The Mexican mining company AMM also saw major expansion by 1852. Having taken advantage of incentives to precure mercury mining in Mexico in the 1830s, it managed to establish various operations in the 1840s in states like Michoacán, Zacatecas, and Guanajuato becoming a major supplier of mercury to even the foreign mining interests in the Bajio region. 1853 marked the arrival of Francis Rule, a Cornish man who, along with many other Cornish miners, left his home in Great Britain seeking fortunes elsewhere. Rule arrived to Mexico as a teenager and began working in the mines of Real Monte y Pachuca and along with him many followed brining in their modern expertise and equipment that would revive Mexico’s mining industry as it began to stagnate. [5]

This period, known as the Little Mexican Industrial Revolution (1840-1860) owed its origins from Lucas Aleman’s early promotion of industry through the expansion of textile mills into early factories by the 1840’s. The development of textile industry and cotton production provides an excellent look into how Mexican industry developed and grew in the years before and after the North American War. During the War, Mexican cotton production began to increase providing cotton for both domestic production and export to the UK. Some of these early mills had evolved into notable companies by the end of the war such as La Constancia Mexicana, Cocolapan, and Industrial Jalapeña [4] operating dozens of factories throughout central Mexico. Piña y Cuevas began promoting via tax incentives and low interest loans the production of cotton in eastern Texas and Oaxaca prompting those companies to invest in setting up a factory each around Galvez bay and investing in its port. Cayetano Rubio and Guillermo Dursina, merchants who initially dealt in the textile trade became successful financiers and speculators helped from Mexico’s private financial sector partnering up to form Finacieria Rubio y Dursina (FRyD)[6]. While initially focusing on the textile industry in the late 1830s, they expanded to iron and steel mills as well as some early shoe and cement factories. Rubio and Dursina were the first of the super-rich industrialists who supported liberal politics in opposition to the conservative hacendados who focused their economic activity on gaining wealth via plantations using their large haciendas and labor that was often described as being not slavery in name only. By 1853 Mexico had over 162 textile mills/factories producing nearly 15,000 tons of yarn [5]. By the end of the decade Mexico began providing serious competition on the world market. The growth of Textile Mills was followed in the late 1840s by the establishment of a lumber production in Campeche followed by the development of artisan goods in southern Mexico by the construction of small factories in Chiapas and Oaxaca

Old factory "La Constancia Mexicana" in Puebla, first factory to use hydrolics and one of the first textile factories in Mexico [d]

Mexican factories largely relied on capital imports mainly from the UK (a situation that is copied throughout the former Spanish colonies thanks to British influence in the region). But to keep up with demand, in the 1840s new loans were given to the development of machine parts factories in an effort to keep the prices of Mexican textiles competitive in the world market. The war saved Mexico from having to deal with reparations from the British as they saw Mexico as one of several sources of grain and cotton absent US production. One bright side to the traditionalist party was a notable decrease of tariffs that allowed the importation of capital goods which in turn helped boost other industries throughout the 1840s. It’s the growth of these factories that attracted many of immigrants from Europe and New England to stop in Central Mexico instead of proceeding to Alta California, many of these were experienced factory workers in their old homes, such was the case with Andres Carnegie’s family.

Andres Carnegie’s father was a Scottish handloom weaver. Following in the lead of many Irish migrants, the Carnegies set their fortunes for Mexico during the war’s blockade of the US, which was their first choice. At the time, the British flag and nationality was enough to enter unquestioned into Mexico, had his family attempted to move to Mexico in the 50’s, their protestant beliefs would have disqualified them from entering the country. They had arrived in Oaxaca where his family quickly got jobs working in a cotton mill where Andres worked as a bobbin boy changing the spools of thread in the mill.

The young Carnegie eventually found himself working in of Herrera’s pet projects, the establishment of a wide system of telegrams. From 1849 to 1851 Herrera pushed for funding of various telegram lines between the main cities of Central Mexico and some of the major outlying cities such as Monterrey (Nuevo Leon), Santa Fe, Hermosillo, Oaxaca and Merida. The young Carnegie began working for an early telegram company and then a railroad company by the mid-1850s eventually finding himself at the head of a major company rivaling FRyD.

A side glance to the West

A side effect of increased textile production led was the decrease of its importation. British interests were offset thanks to Mexico’s reliance on its capital goods. As for the west, luxury imports began replacing general textiles. The Manila Galleon was largely restored in the late 1830s, but by the 1850s many upper-class Mexicans began developing a taste for all sorts of East Asian goods. The Marquesas islands had been a long ignored Mexican possession hosting only a few Mexican colonists growing some minor crops and involved in fishing. During the 1830s, 300 ranchers had settled in the Hawaiian Kingdom to assist in cattle ranching, interest grew in establishing a Mexican trade port there now that the Francisco Bay became a major port for Mexico.

The most ambitious found themselves dreaming of the Mexican flag planted in far off Spanish islands in the Pacific facilitating more trade with the Philippines, nationalists would dream of Mexico City once again administering those Islands as it once did as the Viceroyalty of New Spain. The old nationalist notions of replacing Spain in the world order began to resurface in Mexico. These developments are, at this point, mere curiosities. Mexico’s Pacific Squadron (with two Ships of the Line and three frigates and nearly a dozen support ships of varying sizes) was respectable, but could hardly deal with Mexico’s commitments let alone support any more acquisitions in the Pacific. This led to a push in Herrera’s administration to increase Mexico’s naval might in the Pacific, however the focus remained in the Gulf of Mexico where Herrera began working on ordering modern ships from the UK, France, and the US although the latter was rather reluctant. Nonetheless, two new steam frigates were acquired for the Pacific Squadron in 1853 with the first ever indigenous construction of a brig. Mazatlán had developed a dockyard capable of building small to medium sized ships with Acapulco constructing a larger shipyard. This was only possible due to investments from foreign companies who made their fortune in selling passages to Alta California.

Education and Gender Politics

El Iris, an early female based publication in Mexico started in 1826 [g]

By the early 1820s, less than 10% of Mexicans were able to read and much less able to write with the vast majority of that 10% being made up by the upper classes. When it came to women, that percentage was even lower. Women participating in commercial ventures and working outside the home was not uncommon, but it was not considered preferable. Women often found themselves working on the margins with men and schooling for girls was no different. The 1840s saw little advance in gender politics of Mexico, however initial literacy programs in the 1830s began yielding fruit. A new generation of teenage boys began entering the workforce as they reached adulthood. Literacy among them afforded them jobs in Mexico’s industrializing sectors and with them a few young women followed.

These women who received some practical schooling, including literacy, were the product of a growing undercurrent of Mexican liberalism that saw value in educated and productive women. Legally, women were allowed to work and do business with the permission of their husbands, among other requirements. Liberal men were all to happy to acquiesced to their wives and daughter’s wishes. Some fathers even had tutors teach their daughters, the poorer had their daughter’s siblings do the deed. This was largely a rare phenomenon mostly concentrated among the nascent middle class.

The conservative pushback against women’s rights focused on accusations of impropriety among women who exercised any unapproved level of agency, they were seen as threating to society. Anything that distracted from their role in the family would only lead to its dissolution and thus the downfall of society. Proponents of women’s rights were accused of protestant sympathies and being socialists. The Syracuse convention of 1852 in the US was accused of having a Jewish woman “abusing” scripture. [7]

Liberals, however, did not share these notions. Many saw the successful reign of the rather young (at her start at least) Portuguese Queen Maria II as proof of women’s ability to perform in typical male spheres, then there was the example of Queen Victoria, Queen Isabella of Castile, and some savvy orators even pointed out that it was the Queen of Sheba, and not the King, who recognized King Solomon’s wisdom in the biblical story. To liberals, women clearly had a role to play. It wasn’t just liberal men making their voices heard either, as women themselves would harken to the deeds of Josefa Ortiz and other illustrious women of action that helped win independence for Mexico and the symbolic life of Juna Ines de Asbaje. Malinche, the young female translator of Hernan Cortes, was also recruited in their defense showing how wars and peoples have been shaped by the female voice. The active role of women times of war was a tradition in the Spanish republics, one that presented a contradiction between the passive ideal of femininity and its active assertion in war to preservation of those republics. This formed an image “Mother of the republic” in the imagination of many.

Isabel Ogazon Velazquez was one such female voices. Having been born in 1810, she grew up not knowing of Spanish oppression. By the time she was an adult, Mexico was an established nation. She worked with several prominent men pushing for women’s rights among the constitutionalist party. Her son, Ignacio Luis Vallarta y Ogazon a constitutionalist politician, philosopher and lawyer, would hold liberal views largely influenced by her. Wealthy liberal women who had the support of their husbands helped fund the opening of schools for girls and the development of female teachers even during the traditionalist government of Bustamante. Herrera, a member of the more moderate liberal party, was reluctant to formalize such schools but allowed them to continue as private ventures. Some of the early female graduates went on to tutor girls from lower classes claiming to be educating them in proper Christian principles that required studying, and thus the ability to read.

Isabel Prieto de Landázuri [f]

There were, however, examples of women who gained notoriety in Mexico not simply as wives, but as promoters of culture and literature. One such woman was Isabel Prieto de Landázuri whose family immigrated from Spain to Mexico in the 1830s and went on to write a series of poems and plays. She began to gain public notoriety in the early 1850s inspiring other women to follow suit. In the early 1820s, several publications called to attention of the contributions of women such as

El Aguila Mexicana and

El Iris. In the 1850s a new generation of publications took a step forward calling for larger participation of women such as the

La Semana de las Señoritas Mexicanas and

La Semana de Las Señoritas which inspired many women to write literary works for the publication awakening a new sense of self-worth. This would eventually lead to female publishers later in the 19th century and the rise of the Mexican Feminist Movement.

An effect these developments produced was the increased desire for education among all the classes in Mexico, primarily boys. By 1850 the literacy rate was roughly around 23%, more than twice the rate during the early 1820s. An increase in funding for schools was pushed by Herrera further alienating the church who saw itself as the sole purveyor of education in Mexico, a position challenged after the 1853 elections that brought in the first Constitutionalist president, Juan Alvarez. One of his first acts was to institute a large public-school system with the goals of establishing basic schooling for young children in the rural communities of Mexico and setting up schools for girls in major cities formalizing a system that was until then largely informal and privately run. Among the girls who formed the first classes of these new schools (both private and public) were future feminist icons such as Laureana Wright de Kleinhans, Rita Cetina Gutierrez, María Cristina Farfán Manzanilla, and Laura Mendez de Cuenca as well as other young girls who benefited from formalized education early on such as the Spanish born Isabel Prieto who would become a well-known patron of the arts. [8]

These high society women would often patronize a wide variety of artists from Catalan immigrant Pelegri Clave who specialized in depiction of high society to Mexican born Felipe Santiago Gutierrez who painted more common scenes and portraits. Lanscapes were also all the rage in the art scene such as those painted by another Mexican born artists, Casimiro Castro. Among the arts supported by women, was a divergent take on Constumbrismo, an imported style popularized by European artists as well as Mexican Artists such as Jose Tomas de Cuellar, also known as Fecundo, a North American War veteran. Costumbirsmo was a Spanish style often satirical in nature that depicted traditional scenes. In Mexico, this was becoming coopted by liberal nationalists especially in light of the revelations of the treatment of the Mayans in the Yucatan and attacks on the Pueblo peoples. Some prominent liberal women began influencing the subversive capacity of costumbrismo artists making it into a new Mexican offshoot of the original Spanish intent. It was also the beginning of a shift from focusing on Mexico’s criollo population to its mestizo and indigenous populations.[9]

Juan Alvarez and the Constitutional Convention of 1856

Juan Alvarez, first Constitutionalist President of Mexico [h]

President Herrera opted out of running for reelection and instead handpicked his successor, his vice president Ignacio Comonfort to run in the liberal party ticket. Bustamante had changed the process of selection of the vice-presidency during his first term after having revived it. Instead of having the candidate who won the second highest number of votes become the vice president, the president elect would nominate a choice from a list of candidates in his party (or independents nominated by notable electors) and be approved by the Congress, a process that didn’t need to be repeated after a reelection. Herrera interpreted the office as also being a placeholder for a successor and thus chose Ignacio Comonfort back in 1849 with the intention of having him run to replace him. [10]

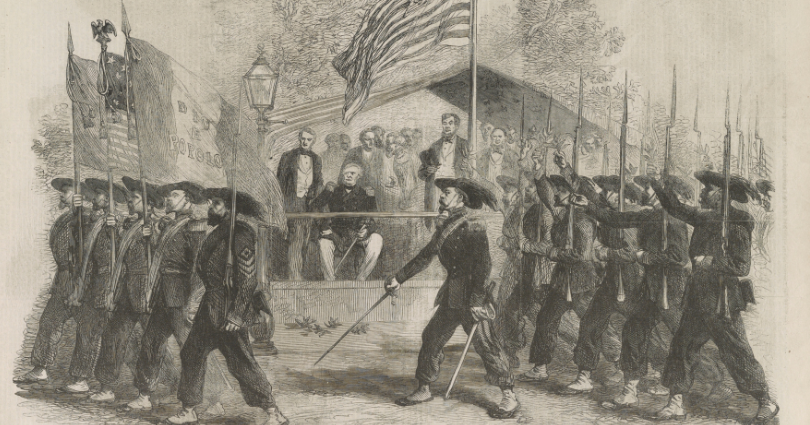

Running against Comonfort was Juan Alvarez for the constitutionalist party and Felix Maria Zuloaga for the traditionalist party. Reactionaries in Mexico were aging and tarnished by the rumors surrounding Bustamante that helped cost him the 1849 elections. In the 1850s a new generation of Mexicans were arriving on the national political scene, Mexicans who were never Novohispanos and were either born after the consummation of independence or too young to remember anything of it. Reactionaries and their views seemed foreign, and at odds with modern realities to this new generation of Mexicans. That said, reactionaries still held a lot of sympathy among the conservative factions who had either allied themselves with the traditionalist or the liberal party depending on how far right on the political spectrum they were. Despite its name, the liberal party was more of a moderate party where the constitutionalists became the champions of liberalism in Mexico.

The elections resulted in a close victory for Juan Alvarez who won about 42% of the votes with Comonfort winning 38% and the traditionalists at a low 20%. Alvarez ran on the promise to modernize the constitution claiming that the old constitution was unproportionally influenced by opportunistic royalists who jumped ship at the last minute during the war for independence. He argued that they should never have been accepted and that they should have been deported with the peninsulares they loved so much, often times using some colorful language to describe their affection to the peninsulares. He made a huge deal of comparing them to the traditionalist party and questioning the loyalties of the liberal party. Constitutionalists saw this win as a referendum on what it truly meant to be “Mexican” and a call to arms to excise the remaining colonial remnant from Mexican politics. Zuloaga would later claim that it was the constitutionalists that started the Reform War by firing the first shots during the elections.

Juan Alvarez began a series of reforms taking advantage of a congressional majority formed by a coalition of constitutionalists and liberal party members who favored several reforms. He appointed the Oaxaca governor, Benito Juarez, to be his vice president a move that awakened many conservatives and reactionaries to begin building a resistance to the constitutionalist government. To many of the conservative elite, the potential for a future Zapotec president was unnerving. Melchor Ocampo was appointed as foreign secretary with Guillermo Prieto as secretary of the treasury who proved to be powerful and influential allies.

The first major reform was the official secularization of public education claiming that the state had no business involving itself in the affairs of the church, a carefully crafted argument meant to mascaraed as being “pro Church”. He continued to pursue more foreign investment and passed a decree ending the prohibition against American immigration to Mexico in late 1853 after another failed filibuster attempt by William Walker. This time around he had infiltrated Alta California via the porous Oregon territory with a band of over one thousand ruffians made up of American settlers in Oregon fleeing from British soldiers and several Americans in Alta California who wanted to pull of what their Texan counterparts were unable to do. They began eliciting support from local English speakers.

Much to the delight of Mexico City, three brigades of miners had formed to support the Alta Californian militia. These brigades were largely formed by Irish immigrants, however there was considerable support from the other immigrant groups. While many American protestants had evaded Mexico’s attempts to keep them out, they formed a minority. Catholics in the US had seen a severe spike in anti-Catholic violence nearly rivaling that of the violence against the Mormons. Many Catholics who had arrived from the US to Alta California had no interest in joining up with Pro-US Walker’s rebellion. Other European immigrants didn’t care much, and while some Mormons still had affinity for the US, many decided to side with Young’s pro-Mexican LDS policies. That’s not to say that there still wasn’t a strong separatist tendency in Alta California, but that separatism in no way aimed towards seeking any relationship with the US. For the most part, Alta Californians were content with their lot. As a result, Walker failed to raise enough support to seriously threaten Mexican control over California.

As the fighting progressed, the Mormon militia in the Deseret Territory had intercepted another group of filibusters attempting to reinforce Walker’s army. Alvarez claimed that the era of disloyal inhabitants and migrants in the north had come to an end having once again expelled Walker who had agreed to surrender as long as a British vessel would take them to neutral territory in Panama, where he surely could cause not trouble. In 1854, after having been rebuffed by the Herrera administration several times, Alta California once again petitioned for statehood. Herrera’s reluctance was based on the fact that it was known that many protestants and East Asians had snuck into the territory. But with the miners’ brigades’ actions during Walker’s attack, Alvarez was convinced that Alta Californians deserved statehood and had the measure pushed through Congress.

In 1855, Alvarez also called for a referendum in the Central American states declaring that Mexico no longer wished to hold them as protectorates. All but Guatemala opted out to gain complete sovereignty. Guatemala applied for statehood along similar lines as Yucatan had once done so. Congress gave Guatemala the same autonomous status that Cuba held and officially recognized that status for the Marquesas Islands.

In 1856, Alvarez called for a constitutional convention to form a new constituent congress to address the old “royalist influences” of the nation’s constitution. Many clergymen, mostly in southern and central Mexico, spoke out against it even encouraging rebellion. Zuloaga himself joined in the calls for rebellion after the new constitution that was drafted included an end to the fueros (Special legal privileges given to military and church officials) , Church land appropriation, further rights given to women such as a right to an education, and the biggest upfront of them all secularization of the nation through a religious freedom clause.

The new constitution was set to take affect after ratification in conjunction with the 1857 elections. A fierce campaign was waged by the traditionalists whose numbers were boosted by an exodus of conservatives from the liberal party. As a last-ditch effort to avoid civil war, party leaders agreed that they should first focus on preventing ratification and if it fails then they should seek to win the elections to undo some of the “damage”. But they couldn’t rally enough support and the new constitution was ratified. Another bow to their plans came in the electoral victory of Alvarez’s successor, Benito Juarez.

In response Zuloaga held a meeting with several prominent conservatives and reactionaires in the archbishop’s palace in Tacubaya in Mexico City and proclaimed the new constitution to be null and void and recognize Zuloaga as Mexico’s legitimate president. Several of the southern states joined in on the call including the state of Sonora (who saw this as an opportunity to gain new privileges by instigating a change of government). Benito Jaurez found himself forced to leave Mexico City as Zuloaga held control of the military there and set up a government in Guanajuato. Throughout the following three months, both sides did little more than fight some skirmishes as different military units figured out which side they backed. By March 8th 1858, the first major battle of the war was fought at Celaya in Mexico State which resulted in a traditionalist victory opening the path to Guanajuato forcing Benito Juarez to move his government north to the constitutionalist stronghold of Monterrey, Nuevo Leon. The War of the Reform had begun.

[1] A term made up for TTL.

[2] In place of OTL Quintana Roo

[3] OTL Utah and Salt Lake respectively

[4] Actual OTL textile mills from the 1830s that survived into the 20th century via loans from Lucas Aleman’s banking scheme.

[5] Same as IOTL. Only his impact will be greater ITTL, an immigrant rival for Andres Carnegie.

[6] These two gentlemen are OTL merchants who purchased import licenses to sell cotton to textile mills using less than admirable tactics which only hurt the industry.

[7] Around 3x OTL numbers

[8] OTL nonsense, sadly.

[9] OTL artists as well as Costumbrismo, however the twist is TTL’s invention, kind of a proto muralismo of OTL that focused on the more indigenous side of Mexico with clear political undertones in the 20th century.

[10] OTL women, ITTL they owe their beginnings to these initial schools as opposed to private tutors.

[11] OTL the vice presidency disappeared after the 1830s for the most part.

[a] Retrieved from

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Guerra_de_Castas.JPG

[.b] I modified one of my modified maps based on wikipedia maps in this page

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Territorial_evolution_of_Mexico

[c] Retrieved from

https://www.maritimeheritage.org/ships/ssBrotherJonathan.html

[d] Photograph by Rleonmx retrieved from

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:La_Constancia_Mexicana.jpg

[e] Retrieved from

http://www1.assumption.edu/ahc/irish/overview.html

[f] By Carlos Prieto de Castro retrieved from

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Isabel_Prieto_de_Landázuri.jpg

[g] Retrieved from

https://paulinanoyola.wordpress.com/2017/02/25/el-iris-periodico-critico-literario/

[h] Unclear authorship, retrieved from

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Juan_Alvarez.PNG