Make sure the image link doesn't have "thumb" in it. That will make it look like this.View attachment 627386

So for some reason when I post my Map it looked like this. Did I do something wrong?

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Alternate Wikipedia Infoboxes VI (Do Not Post Current Politics or Political Figures Here)

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Thanks, it workedMake sure the image link doesn't have "thumb" in it. That will make it look like this.

How'd you make the alternate state borders?View attachment 627419

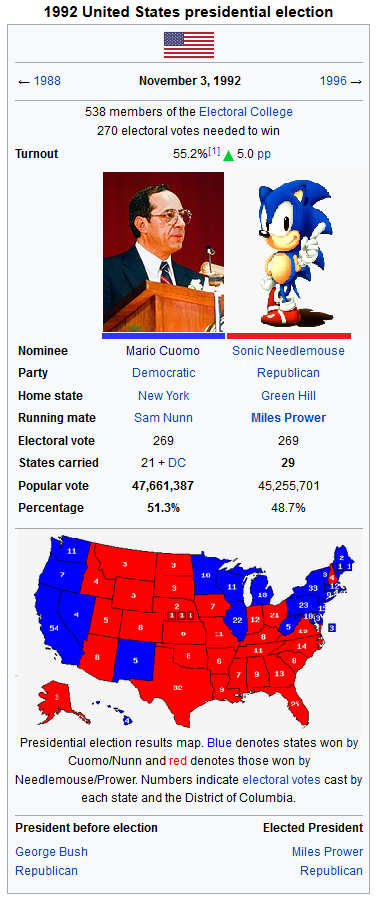

This is pretty much a Remake of my Old Timeline 191 Election maps. I added a Map and fixed the links and votes.

So I download the map to Inkscape, then I click on one of the states. For the south, I click right and choose the delete button. For some like Dakota, I click on the Nodes and then use it to cover the other states' border.How'd you make the alternate state borders?

One more wikiboxe frome my Decembrist Victory TL.

Same wolrd as these:

The Jewish Republic

List of presidents of the Jewish Republic

The First Russian Republic is the name of the regime that existed in Russia after the December Revolution of 1825. On December 14 (26), 1825, liberal-minded guards overthrew the Romanov dynasty. A republic was proclaimed and serfdom abolished. All power passed to the Provisional Government, consisting of members of the secret "Northern Society". Poland and Finland immediately seceded from Russia, and in 1826 there was an uprising in Georgia and an independent Georgian Republic was proclaimed. In 1826, the generals loyal to the monarchy revolted in the south of Russia. The Civil War began. The monarchists (the so-called "Whites") were supported by the Holy Alliance. Austria, Prussia and Sweden began direct intervention in Russia. But to 1828, the Republic was able to repulse an attempt by the Whites and Austrians to take Moscow and regain control of Kiev and other cities of Ukraine.

In 1829 a peace treaty in Riga was signed between the Republic and the Holy Alliance. Austria and Prussia recognized the new government of Russia. In response, Russia ceded Bessarabia to Austria, and the Aland Islands to Sweden. Russia recognized the independence of Poland, Livonia and Finland (all three countries became monarchies). The Jewish Republic was created in Volyn. Georgia gained independence, but as a "sister republic" of Russia.

A few months after the end of the war, General Mikhail Orlov staged a coup. The first republic was replaced by the Russian State - a military dictatorship headed by Orlov.

Same wolrd as these:

The Jewish Republic

List of presidents of the Jewish Republic

The First Russian Republic is the name of the regime that existed in Russia after the December Revolution of 1825. On December 14 (26), 1825, liberal-minded guards overthrew the Romanov dynasty. A republic was proclaimed and serfdom abolished. All power passed to the Provisional Government, consisting of members of the secret "Northern Society". Poland and Finland immediately seceded from Russia, and in 1826 there was an uprising in Georgia and an independent Georgian Republic was proclaimed. In 1826, the generals loyal to the monarchy revolted in the south of Russia. The Civil War began. The monarchists (the so-called "Whites") were supported by the Holy Alliance. Austria, Prussia and Sweden began direct intervention in Russia. But to 1828, the Republic was able to repulse an attempt by the Whites and Austrians to take Moscow and regain control of Kiev and other cities of Ukraine.

In 1829 a peace treaty in Riga was signed between the Republic and the Holy Alliance. Austria and Prussia recognized the new government of Russia. In response, Russia ceded Bessarabia to Austria, and the Aland Islands to Sweden. Russia recognized the independence of Poland, Livonia and Finland (all three countries became monarchies). The Jewish Republic was created in Volyn. Georgia gained independence, but as a "sister republic" of Russia.

A few months after the end of the war, General Mikhail Orlov staged a coup. The first republic was replaced by the Russian State - a military dictatorship headed by Orlov.

Last edited:

Is it still hard as balls?

Yeah... But includes the devs of Shadow of the Colossus.Is it still hard as balls?

Good to know. My problem with the series isn't that it's too hard, but that it's somewhat unfair.Yeah... But includes the devs of Shadow of the Colossus.

But that’s what makes Dark Souls unique.Good to know. My problem with the series isn't that it's too hard, but that it's somewhat unfair.

So this is gonna be apart of an Infobox timeline.

The Failure of the Union has been debated by Scholars for quite some time. It is generally considered however that the main fault of the Short-Lived United States was the Article of Confederation being still around, despite it being seen as a Useless constitution. Meanwhile, Political Polarization rises, with the Federalist and Democratic-Republicans duking it out, making 2020 look like a peaceful event. Finally on January 13, 1801, In response to the Federalists winning the 1800 Election, Georgia announced its plans to succeed from the Union. Eventually in 1804, In response to the DR winning the election, New England also succeeded from the US, however, this was more violent as the United States would not want to lose any more territory. However, with the aid of Vermont (Never join the Union) and Britain, New England succeeded and kicked the Americans out. This pretty much ends the United States, as on May 1, 1807, Jefferson resigned from office aND ON May 9, 1807, congress voted to dissolve the union, becoming efficient on May 10th, thus ending the Failed Experiment that is the United States. The Few States that were generally friendly toward each other, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware, voted to create the United Commonwealth of Columbia, as the successor state of the Union.

So I kinda decided to redo my election wikibox because I honestly didn't feel much satisfaction about it. This one I feel is atleast somewhat of an improvement (like having an actual map) but at the same time is somehow even more fucked than before given who exactly becomes president here.

Philip (Greek: Philippos; 10 June 1921 – ) is King of Greece and a Prince of Denmark since the death of his successor, Paul, in March 1964.

Philip was born into the Greek and Danish royal families. He was born in Greece, but his family was exiled from the country when he was an infant. After being educated in France, Germany, and the United Kingdom, he joined the British Royal Navy in 1939, aged 18. From July 1939, he began corresponding with the 13-year-old future Queen Elizabeth II, whom he had first met in 1934. However they fell out of touch, but have remained good friends from there years on the throne. He would be invited back to Greece following the Second World War, and was declared heir by the sonless King Paul. He would marry British Princess Alexandra in 1957.

Philip and Alexandra have three children: Ann, Queen of Spain; Prince Philip, his heir and Prince Charles of Greece. He is incredibly popular in Greece, having served over a civil war in the 1960s and a dismissed military junta in the 1970s.

A keen sports enthusiast, Philip helped develop the equestrian event of carriage driving. He is a patron, president, or member of over 78 organisations, and he serves as chairman of The King's Award, a self-improvement program for young people aged 14 to 24. He is the longest-serving Greek monarch and the oldest ever member of the Greek royal family. Philip split numerous duties between his sons to enter a semi-retirement on 2 August 2017, aged 96, having completed 22,219 solo engagements since 1964.

Interesting. How's Queen Liz and her alt-universe kids and husband doing?View attachment 627883

Philip (Greek: Philippos; 10 June 1921 – ) is King of Greece and a Prince of Denmark since the death of his successor, Paul, in March 1964.

Philip was born into the Greek and Danish royal families. He was born in Greece, but his family was exiled from the country when he was an infant. After being educated in France, Germany, and the United Kingdom, he joined the British Royal Navy in 1939, aged 18. From July 1939, he began corresponding with the 13-year-old future Queen Elizabeth II, whom he had first met in 1934. However they fell out of touch, but have remained good friends from there years on the throne. He would be invited back to Greece following the Second World War, and was declared heir by the sonless King Paul. He would marry British Princess Alexandra in 1957.

Philip and Alexandra have three children: Ann, Queen of Spain; Prince Philip, his heir and Prince Charles of Greece. He is incredibly popular in Greece, having served over a civil war in the 1960s and a dismissed military junta in the 1970s.

A keen sports enthusiast, Philip helped develop the equestrian event of carriage driving. He is a patron, president, or member of over 78 organisations, and he serves as chairman of The King's Award, a self-improvement program for young people aged 14 to 24. He is the longest-serving Greek monarch and the oldest ever member of the Greek royal family. Philip split numerous duties between his sons to enter a semi-retirement on 2 August 2017, aged 96, having completed 22,219 solo engagements since 1964.

Interesting. How's Queen Liz and her alt-universe kids and husband doing?

Why does the 38 year old Prince Arthur look like he's in his late 40s early 50s?

- Status

- Not open for further replies.

Share: