Yeah, I'll make a list of who's president of what someday.1938-1944 Pedro Aguirre Cerda (radical party)

1944-1950 Gabriel Gonzales Videla (radical party)

1950-1956 Carlos Ibáñez del Campo (independent)

1956-1962 Jorge Alessandri (independent)

1962-1968 Julio Duran Neumann (radical)

1968-1974 Jorge Alessandri (independent)

1974-1980 Eduardo Frei Montalva (Christian Democracy)

1980-1986 Rodomiro Tomic (Christian Democracy)

1986-1992 Eduardo Frei Montalva (Christian Democracy)

1992-1998 Patricio Aylwin (Christian Democracy)

1998-2004 Joaquín Lavín (national party)

2004-2010 María Isabel Allende Bussi (socialist party)

2010-2016 Eduardo Frei Ruiz-Tagle (Christian democracy)

2016-2022 Michel Bachelet (socialist party)

@Vinization

In case you are interested, create a helpful line on your timeline.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

A Drop in the Bucket: Brazil and Latin America in the Cold War

- Thread starter Vinization

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 28 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Part 12: Walking the Rope Part 13: Metamorphosis Foreign Snapshot: Copper, Crosses and Sickles Foreign Snapshot: The Eagle's New Feathers Part 14: 1965 Presidential Election Part 15: 1965-66 Elections Part 16: Full Steam Ahead Part 17: A New Generationmapuche lautarino

Banned

I have several dozen variations in case you are interested

Yeah, I'll make a list of who's president of what someday.

Part 13: Metamorphosis

------------------

Part 13: Metamorphosis

Though some of the Golden Years' most dramatic transformations happened during the Brizola Administration, and many petebistas still tout them, to this day, as achievements brought about by their party's dominance of Brazilian politics in the latter years of that period (or, in some cases, give credit to the president alone for "finishing what Getúlio Vargas started"), just how much the federal government was responsible for causing these changes instead of just taking advantage of an overarching trend that started in the mid to late fifties is still a subject of fierce academic debate. Thus, this chapter will at least try to skirt that dispute entirely.

The most perceptible of all changes was, by far, a marked improvement in the average citizen's standard of living, especially of those who either belonged to the lower classes or lived in far flung places neglected by the authorities for decades or even centuries. The most immediate cause of this phenomenon was a policy of gradual but constant wage increases every year, to the point that the monthly minimum wage jumped from roughly US$ 55,32 in 1961 to US$ 92,76 in 1965, a growth of almost 70% in four years, and the nominal value (in Cr$) rose even further (1). This, combined with the implementation of the thirteenth salary, had the predictable effect of raising the poorest people's purchasing power and thus their quality of life.

Of course, there was more to it than just raising salaries, especially in the Sertão: it's hard to understate the material and psychological impact caused not only by the extension of basic services such as running water and electricity, but also the construction of hundreds of thousands of cisterns and new houses, houses that were built on bricks and cement rather than the wood-and-clay (the infamous pau a pique) ones they steadily replaced. Some argue this process was even more important than that of land reform, but it is important to remember that they walked hand in hand: one ensured the farmers actually owned the plots of land they worked on, while the other made sure they didn't starve to death whenever their crops failed - a common occurrence, thanks to the Northeast's chronic droughts. The economy as a whole was also altered: thanks to several investments made from the 1960s onward, many cities on the banks of the São Francisco river, Juazeiro (BA) and Petrolina (PE) in particular, became increasingly important centers of wine production, even if most of Brazil's vineyards still are, to this day, concentrated in Rio Grande do Sul (2).

As for land reform specifically, what is interesting about this topic is that, according to the original text of the Constitution as it was promulgated in 1946, the federal government already had the power to expropriate and redistribute land, as long as the previous owner was compensated accordingly. It was that last bit that angered groups like the Ligas Camponesas, since they argued that, without a major change in the system, any reform effort would hand over large sums of money to landowners who were not only already quite wealthy, but also often used illegal or forged documents to maintain control of their properties. A new state agency, the National Institute for Agrarian Reform (or INRA, in Portuguese), was founded in November 8, 1962, with the express purpose of coordinating the government's efforts to break up the latifúndios, with the South and Northeast being the regions where it was most active (thanks mainly to the almost incessant judicial, and sometimes even armed, conflicts there). On the legislative level, a constitutional amendment which stipulated that the compensation was to be made through government bonds rather than money was passed by Congress and signed by the president on April 27, 1963 (3).

Part 13: Metamorphosis

Though some of the Golden Years' most dramatic transformations happened during the Brizola Administration, and many petebistas still tout them, to this day, as achievements brought about by their party's dominance of Brazilian politics in the latter years of that period (or, in some cases, give credit to the president alone for "finishing what Getúlio Vargas started"), just how much the federal government was responsible for causing these changes instead of just taking advantage of an overarching trend that started in the mid to late fifties is still a subject of fierce academic debate. Thus, this chapter will at least try to skirt that dispute entirely.

The most perceptible of all changes was, by far, a marked improvement in the average citizen's standard of living, especially of those who either belonged to the lower classes or lived in far flung places neglected by the authorities for decades or even centuries. The most immediate cause of this phenomenon was a policy of gradual but constant wage increases every year, to the point that the monthly minimum wage jumped from roughly US$ 55,32 in 1961 to US$ 92,76 in 1965, a growth of almost 70% in four years, and the nominal value (in Cr$) rose even further (1). This, combined with the implementation of the thirteenth salary, had the predictable effect of raising the poorest people's purchasing power and thus their quality of life.

Of course, there was more to it than just raising salaries, especially in the Sertão: it's hard to understate the material and psychological impact caused not only by the extension of basic services such as running water and electricity, but also the construction of hundreds of thousands of cisterns and new houses, houses that were built on bricks and cement rather than the wood-and-clay (the infamous pau a pique) ones they steadily replaced. Some argue this process was even more important than that of land reform, but it is important to remember that they walked hand in hand: one ensured the farmers actually owned the plots of land they worked on, while the other made sure they didn't starve to death whenever their crops failed - a common occurrence, thanks to the Northeast's chronic droughts. The economy as a whole was also altered: thanks to several investments made from the 1960s onward, many cities on the banks of the São Francisco river, Juazeiro (BA) and Petrolina (PE) in particular, became increasingly important centers of wine production, even if most of Brazil's vineyards still are, to this day, concentrated in Rio Grande do Sul (2).

As for land reform specifically, what is interesting about this topic is that, according to the original text of the Constitution as it was promulgated in 1946, the federal government already had the power to expropriate and redistribute land, as long as the previous owner was compensated accordingly. It was that last bit that angered groups like the Ligas Camponesas, since they argued that, without a major change in the system, any reform effort would hand over large sums of money to landowners who were not only already quite wealthy, but also often used illegal or forged documents to maintain control of their properties. A new state agency, the National Institute for Agrarian Reform (or INRA, in Portuguese), was founded in November 8, 1962, with the express purpose of coordinating the government's efforts to break up the latifúndios, with the South and Northeast being the regions where it was most active (thanks mainly to the almost incessant judicial, and sometimes even armed, conflicts there). On the legislative level, a constitutional amendment which stipulated that the compensation was to be made through government bonds rather than money was passed by Congress and signed by the president on April 27, 1963 (3).

President Brizola signing the amendment.

Another area that was profoundly altered was education. At the beginning of the decade, nearly 40% of all citizens 14 years of age or older were illiterate, a number the federal government sought to reduce by repeating what was done in Rio Grande do Sul from 1955 onward - the construction of thousands of schools - in a national scale. The overwhelming majority of these schools were built in the Northeast, since said region's indicators were even more desperate than the national average, with some municipalities reporting illiteracy rates as high as 60 or even 70%. These appaling numbers, and the government's frantic efforts to diminish them to zero, turned Brazil into a "laboratory" for all sorts of ambitious educators, intellectuals and politicians, all eager to try out new and often unorthodox techniques. Some of the more famous examples of these "experiments" were the Movimento de Cultura Popular (Popular Culture Movement), sponsored by the mayor of Recife, Miguel Arraes, and its counterparts in other northeastern capitals, such as João Pessoa and Natal, and the CNBB's (National Brazilian Bishops' Conference) Movimento de Educação de Base (Basic Education Movement).

But the experiment that reshaped Brazilian education as we know it happened not in a large city or capital, but in Angicos, a little town smack dab in the interior of Rio Grande do Norte. It was there that Paulo Freire, an university professor from Recife, put the ideas he developed over the last few years in motion. With the help of some volunteers (almost all of them university students), the state government, Sudene and even the United States, Freire managed to teach more than 300 rural workers to read and write in just 40 hours (4). It didn't take long for knowledge of the success of the "Paulo Freire Method" to spread throughout the country like wildfire, with many of the institutions and movements mentioned in the previous paragraph adopting it, and for the higher ups at the Ministry of Education to notice just how effective a weapon it could be in their crusade against what they called "poverty of the mind".

Thus, when the federal government launched the Programa Nacional de Alfabetização (National Literacy Program) in January 1964, Freire was predictably chosen to lead it. Though some right-wing politicians and newspapers, like O Globo, criticized the program's emphasis on teaching people not only how to read and write, but also their rights as citizens and workers (leading to ludicrous accusations not worth discussing here), its successes could not be ignored: roughly two million adults were were benefited by the program, exceeding the Rio de Janeiro's expectations, by the end of the year (5). Six years later, in 1970, Brizola's successor as president triumphantly declared that illiteracy had been eradicated in Brazil, thanks to the tireless work of millions of teachers, bureaucracts, volunteers and, of course, Paulo Freire himself, who became an international star and would soon be invited by other countries' governments to advise them on how to sort out their educational problems.

Paulo Freire in November 1963.

Art and culture blossomed during the 1960s, thanks in no small part to the further massification of means of communication such as TVs, which became an increasingly common sight in Brazilian households thanks to the virtuous cycle of decreasing costs and rising salaries. While traditional music and movie styles like the bossa nova Hollywood-esque films were still the norm, and in fact reached their peak during this decade, Brazilian art as a whole took an increasingly political direction, which can be most clearly seen in the Cinema Novo (New Cinema) and the works of directors such as Glauber Rocha, Nelson Pereira dos Santos and Eduardo Coutinho, each of whom sought to reveal and denounce the injustices of Brazil's "feudal" interior. One of the most famous and successful examples of a Cinema Novo film was Cabra Marcado para Morrer ("Marked for Death"), a partially fictional take on the life of João Pedro Teixeira, a peasant union leader from the state of Paraíba who was murdered on the orders of local landowners in April 1962 (6).

Theatre was another artistic genre profoundly affected by the socio-political climate of the 1960s, though its own, gradual transformation began much earlier, arguably in the mid 1940s, due to the work of work of Abdias do Nascimento and his Teatro Experimental do Negro, whose purpose, like its name says, was to combat racism and rescue Brazil's African heritage, repressed and buried by the authorities for generations (7). It was during this decade that the career of other important playwrights, like Augusto Boal and Gianfrancesco Guarneri, took off in force, and that the Centro Popular de Cultura (Center for Popular Culture), a group of left-wing intellectuals associated with UNE (National Students' Union) who sought to disseminate "popular revolutionary art" to the population, was organized.

Abdias do Nascimento and Augusto Boal: playwrights, partners, politicians.

The last area to be addressed, and the one most people remember, is technology. While Brazil's industrialization arguably began in the 1940s, with the creation of the Companhia Siderúrgica Nacional, and made great strides in the following decade thanks to the developmentalist policies of the Second Vargas and Etelvino administrations, it was during the 1960s that the country truly became an urban, industrial nation. And much like Argentina and Mexico built up their industrial sectors to create at home products they once imported, Brazil did the exact same thing, even as foreign companies held a good share of the national market in various sectors, especially the automotive one. In spite of this, however, the overall context of the time was actually quite favourable for the occasional ambitious businessman, thanks to the existence of high tariffs that made imported products artificially expensive: it was during this decade that Gurgel and Puma were founded, after all, and more companies would follow their footsteps in the 1970s, such as Miura and Hofstetter (8).

Another branch which made its first steps was aeronautics. Though the government's first attempts to foster this specific industry started in the 1930s, they either never materialized or otherwise didn't meet the desired results, and it was only in the 1950s that it started to make some genuine progress. It was in that decade that the first drafts for what would be Brazil's first helicopter, the IPD BF-1 Beija-Flor (Hummingbird), were made by German aviation pioneer Henrich Focke (of Focke-Wulf fame), but most of the work on the project would be made by another German engineer, Hans Swoboda, with help and funding from the Centro Técnico de Aeronáutica (Technical Center for Aeronautics). After years of designing and testing, the first prototype was finally finished in 1958, and its first flight happened in February 1960 - but although said flight was a success, it became clear for the planners that more modifications were required before the Beija-Flor became a viable product. Two more prototypes were built, and after five more years of tests, each showing increasingly promising results, until it was finally deemed worthy of mass production in 1966 (9).

Needless to say, the Beija-Flor was a massive success: for a country with such a gigantic territory and so many distant corners that barely had any roads, a small, manouverable, two-seated helicopter capable of delivering cargo and people relatively quickly was nothing short of a godsend, one that would soon be exported to countries with a similar profile and needs to Brazil's. And it wouldn't take long for some ambitious Brazilians to start believing that their country was capable of building not only helicopters, but also airplanes, and for other equally ambitious individuals to realize how useful these advances could be for the Armed Forces.

Another branch which made its first steps was aeronautics. Though the government's first attempts to foster this specific industry started in the 1930s, they either never materialized or otherwise didn't meet the desired results, and it was only in the 1950s that it started to make some genuine progress. It was in that decade that the first drafts for what would be Brazil's first helicopter, the IPD BF-1 Beija-Flor (Hummingbird), were made by German aviation pioneer Henrich Focke (of Focke-Wulf fame), but most of the work on the project would be made by another German engineer, Hans Swoboda, with help and funding from the Centro Técnico de Aeronáutica (Technical Center for Aeronautics). After years of designing and testing, the first prototype was finally finished in 1958, and its first flight happened in February 1960 - but although said flight was a success, it became clear for the planners that more modifications were required before the Beija-Flor became a viable product. Two more prototypes were built, and after five more years of tests, each showing increasingly promising results, until it was finally deemed worthy of mass production in 1966 (9).

Needless to say, the Beija-Flor was a massive success: for a country with such a gigantic territory and so many distant corners that barely had any roads, a small, manouverable, two-seated helicopter capable of delivering cargo and people relatively quickly was nothing short of a godsend, one that would soon be exported to countries with a similar profile and needs to Brazil's. And it wouldn't take long for some ambitious Brazilians to start believing that their country was capable of building not only helicopters, but also airplanes, and for other equally ambitious individuals to realize how useful these advances could be for the Armed Forces.

The first prototype of the Beija-Flor.

------------------

Notes:

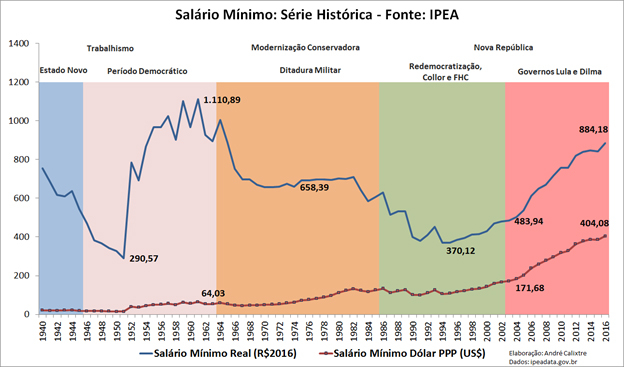

(1) I'm using this graphic as a reference:

The blue line is the minimum wage in reais (R$) and the red one in dollars. As you can see, it cratered after 1964, fell even further during the eighties, and only began to slowly recover from the mid nineties onward.

(2) This is OTL.

(3) João Goular signed a decree establishing pretty much the same thing on March 13 1964, days before the coup.

(4) This is all OTL, and yes, even the bit about the US funding him!

(5) IOTL the program had barely begun to function before the coup happened, and it was shut down shortly after. Because teaching people to read and write is communism, apparently.

(6) IOTL the work on Cabra Marcado para Morrer was interrupted by the coup, with many actors (who were actually land reform activists) being arrested and part of the filming equipment confiscated. Coutinho got back to work on the movie 17 years later, when the dictatorship finally began to ease up on the censorship, and since the kind of movie he was planning to make in the sixties just wouldn't cut it anymore (it was too different a context), he chose instead to make a documentary on the lives of the people who worked on the scrapped version, a group that included João Pedro's widow, Elizabeth Teixeira, and their children.

Here's a version I found on Youtube, which I strongly recommend you seeing if you have enough free time and a reasonable grasp of the Portuguese language. It's a very enlightening look on what Brazil was like in the sixties and eighties.

(7) IOTL the Teatro Experimental do Negro was shut down by the dictatorship.

(8) Brazil had a few native automobile manufacturers IOTL, Gurgel being the most famous and successful of them by far, but none of them survived the double whammy of the Lost Decade and the Collor administration's opening of the national market in the early 90s.

(9) IOTL the Beija-Flor project was cancelled after an accident that completely destroyed one of the prototypes in 1965. Embraer may have risen to prominence a few years later, but it was still an unfortunate loss.

Notes:

(1) I'm using this graphic as a reference:

The blue line is the minimum wage in reais (R$) and the red one in dollars. As you can see, it cratered after 1964, fell even further during the eighties, and only began to slowly recover from the mid nineties onward.

(2) This is OTL.

(3) João Goular signed a decree establishing pretty much the same thing on March 13 1964, days before the coup.

(4) This is all OTL, and yes, even the bit about the US funding him!

(5) IOTL the program had barely begun to function before the coup happened, and it was shut down shortly after. Because teaching people to read and write is communism, apparently.

(6) IOTL the work on Cabra Marcado para Morrer was interrupted by the coup, with many actors (who were actually land reform activists) being arrested and part of the filming equipment confiscated. Coutinho got back to work on the movie 17 years later, when the dictatorship finally began to ease up on the censorship, and since the kind of movie he was planning to make in the sixties just wouldn't cut it anymore (it was too different a context), he chose instead to make a documentary on the lives of the people who worked on the scrapped version, a group that included João Pedro's widow, Elizabeth Teixeira, and their children.

Here's a version I found on Youtube, which I strongly recommend you seeing if you have enough free time and a reasonable grasp of the Portuguese language. It's a very enlightening look on what Brazil was like in the sixties and eighties.

(7) IOTL the Teatro Experimental do Negro was shut down by the dictatorship.

(8) Brazil had a few native automobile manufacturers IOTL, Gurgel being the most famous and successful of them by far, but none of them survived the double whammy of the Lost Decade and the Collor administration's opening of the national market in the early 90s.

(9) IOTL the Beija-Flor project was cancelled after an accident that completely destroyed one of the prototypes in 1965. Embraer may have risen to prominence a few years later, but it was still an unfortunate loss.

Very glad to not only seeing this back, but also the way you're developing Brazil, the culture part especially and the Paulo Freire bit was amazing to read. Good job as always.

Great as always. So IOTL Helibras was founded in1978 as a subsidiary of Airbus Helicopters in Brasil, can we say that ITTL Helibras is founded to mass produce the Beija-flor? If opposition to State owned industries is too big Brizola could throw them a bone and make the industries mixed capital with the civilian production open to trade and the military wing, declared a strategic industry, owned by the State. You can apply this to pretty much everyone, Engesa, Agrale, Imbel, etc.

Not to be nitpicky, but i reread your post about Brizola's cabinet and found something kinda weird, Ney Braga as agriculture minister? As a paranáense i just find it weird for a man who took an active role in fighting the rural worker's movement(West and Southwest Paraná was a region of unrest, to this day the region is quite left leaning) as Bento Munhoz's chief of police and as governor himself, served as minister under the dictatorship and ran against the PTB's candidate for the mayorship of Curitiba(who happened to be Requião's father) and overall strikes me as Adhemar Barros made in Paraná, so it's a bit weird to see someone like that occupying such an important position in Brizola's goverment, wouldn't he hurt the land reforms?

Though on the other hand, he was Munhoz's in-law, and also friends with Castelo Branco and the Geisel brothers, so maybe he was indicated by one of them.

Awesome post, as usual.

Edit: And i gotta say, at least Naves is governor instead of Braga ITTL 🙏

Though on the other hand, he was Munhoz's in-law, and also friends with Castelo Branco and the Geisel brothers, so maybe he was indicated by one of them.

Awesome post, as usual.

Edit: And i gotta say, at least Naves is governor instead of Braga ITTL 🙏

Last edited:

Huh, I knew Braga was fairly right-wing, but not that right-wing (even with his involvement with the dictatorship and all). To be honest I chose him mostly because I didn't know of any other prominent-ish Christian Democrat at the time, and I didn't want to put Montoro there since he's still governor of São Paulo. I completely forgot about Wallace Tadeu de Mello e Silva, might as well put him there instead.Not to be nitpicky, but i reread your post about Brizola's cabinet and found something kinda weird, Ney Braga as agriculture minister? As a paranáense i just find it weird for a man who took an active role in fighting the rural worker's movement(West and Southwest Paraná was a region of unrest, to this day the region is quite left leaning) as Bento Munhoz's chief of police and as governor himself, served as minister under the dictatorship and ran against the PTB's candidate for the mayorship of Curitiba(who happened to be Requião's father) and overall strikes me as Adhemar Barros made in Paraná, so it's a bit weird to see someone like that occupying such an important position in Brizola's goverment, wouldn't he hurt the land reforms?

Though on the other hand, he was Munhoz's in-law, and also friends with Castelo Branco and the Geisel brothers, so maybe he was indicated by one of them.

Awesome post, as usual.

Edit: And i gotta say, at least Naves is governor instead of Braga ITTL 🙏

I have three ideas: Nelson Maculan, leader of the PTB in Paraná and who had experience in the agro industry when he owned a business of coffee transport and rural machinery in his home city of Londrina; Plinio de Arruda Sampaio, from the PDC(and of the pro-PTB wing of the party at that!) and was even member of the goverment's comission for land reform, though OTL he only began his political career in 1959; Picking someone from JK or Jango's OTL cabinets.Huh, I knew Braga was fairly right-wing, but not that right-wing (even with his involvement with the dictatorship and all). To be honest I chose him mostly because I didn't know of any other prominent-ish Christian Democrat at the time, and I didn't want to put Montoro there since he's still governor of São Paulo. I completely forgot about Wallace Tadeu de Mello e Silva, might as well put him there instead.

Last edited:

Pretty much, he never rises to prominence thanks to his narrow loss to Ademar de Barros ITTL.Btw what happened to our boy Janio Quadros? Did he gave up politics?

Perfect, I'll go with Maculan.I have three ideas: Nelson Maculan, leader of the PTB in Paraná and who had experience in the agro industry when he owned a business of coffee transport and rural machinery in his home city of Londrina; Plinio de Arruda Sampaio, from the PDC(and of the pro-PTB wing of the party at that!) and was even member of the goverment's comission for land reform, though OTL he only began his political career in 1959; Picking someone from JK or Jango's OTL cabinets.

Nordeste em peso ! Potiguar speaking, how big will be the nordestino migration to the Southeast ITL ?O

Opa! Irmãos do nordeste! And me completing the obrigatory Baiano presence.

Probably still large, as long as there economic opportunities in other parts of the country, people in the poorest region (despite all it's improvements) will move there, although hopefully we won't see any favelas Poppin up due to lessened immigration and better government.Nordeste em peso ! Potiguar speaking, how big will be the nordestino migration to the Southeast ITL ?

You could do "where are them now?" posts like the ones in La Larga y Oscura Noche, detailing the changes caused by the butterflies to their career(ie: Luiz Gonzaga being overshadowed by the coming of Bossa Nova (OTL) and the rise in social status of northeasterns (ITTL), who afaik never reallly dropped the King of Baião for Bossa (IRL he stayed relevant becuse of the military rule). Just a suggestion/idea i had that would broaden the world building.

La Larga y Oscura Noche

The Spanish Civil War started in 1936 and ended in 1939, as I am sure you know. I supposed that, due to the context, it was very clear I was talking just about the 1970s. Anyway, it is not that important for the TL context, and this is deviating the attention from the important aspects of it...

www.alternatehistory.com

Good idea, but I can't make a promise. Even if I don't make detailed posts on specific people, however, I'll try to sprinkle some things in future updates.You could do "where are them now?" posts like the ones in La Larga y Oscura Noche, detailing the changes caused by the butterflies to their career(ie: Luiz Gonzaga being overshadowed by the coming of Bossa Nova (OTL) and the rise in social status of northeasterns (ITTL), who afaik never reallly dropped the King of Baião for Bossa (IRL he stayed relevant becuse of the military rule). Just a suggestion/idea i had that would broaden the world building.

La Larga y Oscura Noche

The Spanish Civil War started in 1936 and ended in 1939, as I am sure you know. I supposed that, due to the context, it was very clear I was talking just about the 1970s. Anyway, it is not that important for the TL context, and this is deviating the attention from the important aspects of it...www.alternatehistory.com

Threadmarks

View all 28 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Part 12: Walking the Rope Part 13: Metamorphosis Foreign Snapshot: Copper, Crosses and Sickles Foreign Snapshot: The Eagle's New Feathers Part 14: 1965 Presidential Election Part 15: 1965-66 Elections Part 16: Full Steam Ahead Part 17: A New Generation

Share: