The United States

Francis Boott has returned from Italy to enroll in Harvard. He already knows more about music than his teachers. He misses his friend Jeff, who’s still in Italy studying, but it was with a certain relief that he returned home—his teachers in Italy couldn’t help seeing him as a mediocrity by comparison to his friend the obvious genius. He’s made a small amount of money for himself by publishing the hymns and love songs he’s been writing over the past few years, but the only song of his that’s caught on with the public is “Thimmon, Thimmon, Thimmon Our Lives Together,” the title of which will make sense in a moment.

Boott also sold his account of his and Jeff’s adventure in the Austro-Italian War to Horace Greeley’s

New York News & Literature, where it appeared alongside a new poem by Edgar Allen Poe, who is starting to realize that leaving the Army was a mistake. This is not a good economy to be a full-time writer in, and he has to look after his brother Henry, who used Stabler’s morphine to help him overcome his addiction to alcohol… and is now addicted to morphine.[1] Being the designated functional adult of the family is a new experience for Edgar, and it won’t get easier next year when he applies for a license to marry his 15-year-old cousin Virginia.[2]

As for Boott, wherever he goes in Cambridge or Boston, he sees shops closed and boarded up, grand homes likewise boarded up or advertised as rental properties, people begging for spare change in threadbare clothes that were once fine. Even merchant ships linger by the docks for weeks or months, waiting for a commercial voyage. It seems like the biggest events are the sheriff’s auctions where the property of the bankrupt can be had at a third or a fourth of its estimated value. And those auctions might be part of the problem—if you’re a woodworker or a horse dealer, or anyone in a number of different trades, how do you sell your product at any kind of reasonable price when so many people are willing to wait and see if they can get it at the next auction for less than you paid to make or obtain it?

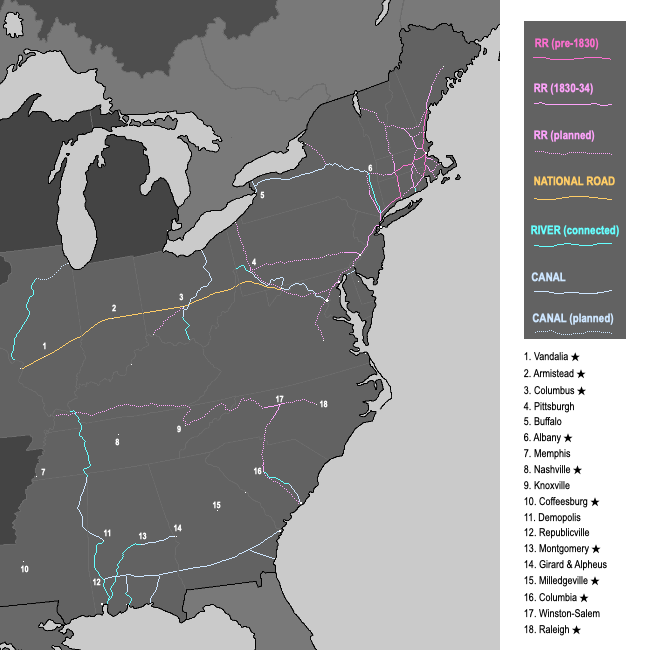

Sure, if you can afford a railway ticket you can go to New York or Philadelphia, or up into Maine or New Hampshire, in a matter of hours, and that will change life for everyone in ways no one realizes yet. But right now, things are just as bad in those places. And the story is the same in Baltimore (where Poe is living with his brother), Charleston, Mobile, and Savannah—especially Savannah, which is trying to rebuild itself at a time when investment capital is in short supply and insurance can hardly be found at all. The one bright spot in the economic gloom is the introduction of the Thimmonier machine, or just “thimmonier,” which France started exporting to the United States two years ago—and that’s only a bright spot if you have money enough to afford one and don’t wish to pay a tailor or seamstress. If you

are a tailor or seamstress, it’s one more piece of bad news. Professional sewing takes long experience, but what the anglophone world now calls “thimmoning”—sewing by machine—produces a more reliable seam, and anyone with a machine can do it. (Isaac Singer and Elias Howe are making their own versions, of course, which are resulting in some very nasty letters from the French consulate in New York.)

On the larger scale, everyone knows something has gone terribly wrong, but no one knows what. President Sergeant’s Secretary of the Treasury, Martin Van Buren, is trying to expand his department. He wants the Treasury to be independent from the Bank, and he also just wants to be able to collect enough information to assess the damage. He wishes he had a machine like these “difference engines” he’s been hearing about, that the Exchequer and the Bank of England are using in London. As it is, he feels like a doctor trying to diagnose an illness by listening to screams of pain from outside the house.

One thing he’s figured out is that canals weren’t the only bubble swelling the U.S. economy through all those happy years. Land prices were rising steadily—cotton land in the South, timberland in Maine and general-purpose farmland everywhere. This not only made a lot of people rich, it served as an engine for pushing settlers further and further west in search of something they could actually afford. The Army made this possible, destroying many Native societies and killing a lot of people to open up everything east of the 95th meridian and a fair amount west of it to settlement. Some of this land was sold, mortgaged or speculated on based on the idea that it was going to be the site of a town or city someday. (Even with canals and railroads, it’s still impractical for investors to send somebody out there to look at every single site.)

Not all of the planned towns were fake. Investors are still doing everything they can to make Cairo, Illinois happen. The site is (at least on a map) just too perfect—the junction of the Mississippi and the Ohio, the perfect place to build the greatest city in America. Sure, it’s a flood-prone spit of land that needs levees around it before they can even build anything on it, but as they say in real estate,

location, location, location.

To this end, Kentucky senator and former President Henry Clay arranged for the course of the Raleigh & Mississippi Railroad (which when complete will link the state capital of North Carolina with the Mississippi by way of the Cumberland Gap) to run through southern Kentucky, where the land was cheaper anyway. He also arranged for the site of the third USNU campus (after D.C. and Charleston) to be at Wickliffe, KY, at the western end of the R&M and right across the river from Cairo. The next five, for which sites haven’t been purchased yet, are going to be in Charlotte, North Carolina; Autherley, Georgia; Girard, Alabama; Knoxville, Tennessee; and Chickasaw, Mississippi. It’s not a coincidence that three of those are canal towns (four if you count the Santee Canal) and two of them are along planned railroads—the students have to get there somehow.

In addition to the land business, there’s the cotton business. For a long time, cotton was an investment where you couldn’t lose money if you tried. With mills in Lowell and Liverpool, Manchester and Mulhouse all needing raw fiber, cotton planting could expand as far as the climate allowed into Mississippi and Arkansaw. But a deflationary spiral sucks everything in—when all the potential customers are short of money, cotton dealers can either offer their product at a lower price or feed it to goats. Cotton has dropped from 31¢/kilo at the end of 1832 to 22¢/kilo now[3]. For most of the past year, Nicholas Biddle has been trying to deal with this by using the Bank’s resources to buy enough American cotton to corner the market and stabilize the price.[4] This is not winning him any friends overseas.

In fact, between Biddle playing Monopoly on the world stage and state governments defaulting on their bonds, the only man in Washington whose job is as rough as Van Buren’s is Secretary of State Albert Gallatin. The mood in Great Britain is

furious with the United States, more so than at any time since the ARW—much more so than during the War of 1812, when Lord Liverpool’s government saw Cousin Jonathan’s hissy fit as a minor distraction from the real war against Old Boney. Having what is basically the greatest power in the world angry at you is a scary thing—Secretary of War Thomas Hart Benton has to report that right now the U.S. isn’t ready for any kind of conflict with Britain. Joseph Henry and Walter Hunt, up in Albany, have come up with an invention that may equalize things slightly, but right now it’s still in the prototype stage and nobody’s ready to bet a war on it.

To make matters worse, America’s most loyal ally, France, has also turned rather cold—they lost money on U.S. canal stocks and state bonds too. In Spain, ideological opposition to American ideals has gotten stronger since Carlos took the throne. So the elder statesman Gallatin finds himself spending a lot of time with Italy’s young ambassador to the United States, Massimo Taparelli Marquess of Azeglio. What investment capital Italy has, they mostly use to develop their own country, so they haven’t lost enough in the U.S. to be mad about it. (Also, Massimo d’Azeglio is just a really cool guy to hang out with—soldier, statesman, artist, writer and general Renaissance man.)

It should be noted that when it comes to transatlantic rage, Americans are giving as good as they’re getting. In state legislatures from Maine to Mississippi, legislators are denouncing the British investors who purchased their bonds as foreign leeches trying to use money and debt to achieve the conquest their army and navy failed to accomplish. At first, the British government tried sending lobbyists to state capitals to make sure they didn’t repudiate their debts. All this did was give the state governments somebody to yell at. Arkansaw was the first state to default on its bonds, which is actually kind of impressive when you consider that it only became a state this year.[5] Pennsylvania, Mississippi and Georgia have followed suit, and everyone’s just waiting to see which state defaults next. In Mississippi, state Speaker of the House Alexander G. McNutt was thoughtful enough to introduce an element of anti-Semitism into this already toxic debate. In his denunciation of major bondholder Nathan Mayer Rothschild, McNutt said that “the blood of Judas and Shylock flows in his veins, and he unites the qualities of both his countrymen.”[6] Fortunately, this hasn’t led to any violence against America’s small and uninvolved Jewish community, but it did let the state of Mississippi feel that much more self-righteous about not paying their debts.

The situation is the same with American lending institutions. Nobody ever became a banker for the free hugs, but at times like this they’re especially unpopular. Some plantation owners are simply fleeing, but others are organizing mobs to fight the sheriffs when they come to foreclose. Even the small, free-labor farmers are getting in on the act—Joe Baldy and his Charcoal-Burners are expanding their repertoire from freeing slaves to helping poor farmers organize against foreclosure. (This does create some conflicts of interests, as even small farms sometimes have a slave somewhere on the premises.)

It isn’t just foreigners and bankers that Americans are angry at. The Democratic-Republican Party has held the White House since March of 1801. Even if you count the post-War of 1812, post-Gadsby’s Tavern party as a different party than that of Jefferson and Madison, it will still have had a 20-year run when Sergeant runs for reelection. To give just one example of how enmeshed the DRP is in U.S. institutions, promissory notes issued by the Bank of the United States are mostly printed in black ink, but with the denomination numbers printed in Republican Purple ink (one guess which company manufactures that ink) even though, technically, Republican Purple is a symbol of the Democratic-Republican Party, not the Bank, the Treasury or the nation.

In the aftermath of Bloody May and Wellington’s peace treaty, the alliance that the Dead Roses represented seemed like the thing that would preserve the nation and save the very concept of freedom in the world. At the moment, it seems like a sclerotic and unresponsive political machine that has failed the people it was meant to serve. Add to this everyone who believes their state or locale is losing out in the fight for railroad service due to political shenanigans—Tennessee, for instance, is feeling shafted by the decision to run the R&M through southern Kentucky for the benefit of a possible future metropolis when Nashville and Memphis were already

right freaking there.

And then, of course, there’s the backlash against the spate of anti-slavery legislation in various parts of the South. In Port Royal, Virginia, a highly intellectual young man named George Fitzhugh (part-time attorney, part-time recluse) was badly shaken by the rather mild anti-slavery legislation passed in Virginia this year. He’s tried to get in touch with Thomas Roderick Dew, who wrote so eloquently—he might in fact be the only person alive who read Dew’s hundred-plus-page manifesto all the way through. Alas, Dew has come down with a case of pneumonia and is in bed, being cared for by his wife until he can get his strength back and start writing his latest essay, which will be on the fundamental weakness of women and their need for men to look after them.

In the rest of Virginia and elsewhere in the nation, the Tertium Quids are not only consolidating their hold on the South, but expanding elsewhere. But for those who don’t want to be in a party that champions slavery and has Calhoun for a leader, there are a couple of third parties. There would probably be more, but it takes money to build a party organization, and (it bears repeating) money’s in short supply. For example, the number one backer of the Liberation Party is Levi Coffin, a former member of SINC’s board of directors and the guy most responsible for making sure SINC’s manumissions went through. He’d be a much bigger backer if he hadn’t lost so much money in the SINC stock collapse. The Populists are doing better—their primary backer is railroad magnate Erastus Corning, who’s been going from rich to richer even now.

The result? In the outgoing 23rd United States Congress, the Democratic-Republicans had 186 House seats and the Tertium Quids had 53 seats. In the incoming 24th Congress, there are 110 Dead Roses, 107 Quids and 23 third-party candidates. Nobody’s going to have a majority.

So who’s in these third parties? The Liberation Party, of which William Lloyd Garrison is the founder, has only one issue — slavery. Yes, farmers are struggling to stay afloat and the poor are suffering, but unless they’re being horsewhipped, watching their wives get raped or having their children sold to strangers, they can take lots of seats as far as the Liberationists are concerned. And as for foreign policy, the big bad boogeyman Britain is

abolishing slavery, which is a lot more than the U.S. can say right now. The Liberationists have elected two candidates to the House—a good first try, especially for a party dedicated to winning the votes of white men by telling them to shut up about their problems, but not enough to give them any clout to speak of.

The real clout lies with the Populist Party’s 21-member delegation. This party is also anti-slavery, like its founder, Pennsylvania’s Joseph Ritner[7], who is now preparing to run for governor against incumbent George M. Dallas. This was inevitable—Ritner himself is an abolitionist, and anyone who isn’t hostile to slavery finds it much easier to run as a Quid than as a member of a party that hardly anyone has heard of.

But unlike the Liberationists, the Populists have positions on other issues too. On a lot of things, they’re not that far apart from the DRP—their disagreement is more with the machine than with the agenda. Their main point of contention is debt relief. The theory that the DRP has been operating under is that the Second Bank of the United States and the various state banks must be kept as whole and healthy as possible, so that they can be the engines of recovery. The Populists believe that if blacksmiths and carpenters can just pick up their tools again, fishermen can return to their boats, and especially if farmers can return to their fields, everything else will heal of its own accord. (The Liberationists’ position on the banks is that they’re SEIZING AND AUCTIONING SLAVES, in case you were wondering.)

In Congress, House Speaker Nathaniel Claiborne of Virginia knows he can’t stay in the job even if the DRP manages to form a majority—he barely won reelection himself, and this disaster happened to the party on his watch. The party whip, Rep. John Quincy Adams of Massachusetts, suggests that he use his remaining time in office to form a governing coalition with the Populists, which the Liberationists can join if they don’t feel too unclean about it. The problem is that nobody in the DRP really knows how to do this anymore. It’s been a long time since they had to share power.

Serving as consultant in this matter is one more job for Albert Gallatin, who was ambassador to France and has seen multi-party politics in action. His friend d’Azeglio can’t take part in this, of course—ambassadors of friendly nations are not supposed to assist one party over another—but he introduces them to Alexis and Gustave, two well-educated Frenchmen who’ve spent the last couple of years touring the U.S. and writing down their observations.

Alexis and Gustave have plenty to warn them about. When one party controls the legislature, the key to growing in power and helping your constituents is to be a loyal and reliable party man. When the parties are almost evenly divided, it’s a completely different dynamic. The handful of people whose votes can’t be counted on, who could go either way, who you need to make a deal with to get them on board… those are suddenly the most powerful people in the legislature. In his correspondence with incoming Quid freshmen John Niles of Connecticut, Lewis Cass and Jonathan Sloane of Ohio, and James Buchanan of Pennsylvania, Calhoun is starting to realize this as well—especially on the issue of tariffs.

That’s the House. The Senate (31 DR, 11 TQ) hasn’t changed yet, because senators are still elected by state legislatures. But a lot of state legislatures have changed hands, and a third of the Senate will be up for reelection when they reconvene early next year. So some of the Dead Rose senators are feeling like Wile E. Coyote in the moment when he looks down and realizes he’s over the edge of the cliff.

It isn’t just in Washington that the shock of the midterms is being felt. Newspapers don’t even try to be nonpartisan, and nothing like modern opinion polling really exists yet. Nobody saw this coming, certainly not a 25-year-old lawyer in Vandalia. Between marrying Ann Rutledge and getting his legal career started—all these bankruptcies and cases of land fraud are perfect for keeping a young lawyer busy—Abraham Lincoln hasn’t had much time for politics this year. The closest he’s come has been arguing politics with his younger friend and co-worker Stephen, a recent convert to the Northern Quids. But Lincoln is a loyal Dead Rose, working in the state capital does get you some connections, and seeing the defeat of his party has made him worry about the future of the country.

And it’s not just the loss of the Dead Rose monopoly that bothers him, it’s the setback for the anti-slavery movement. Yes, there are now explicitly anti-slavery parties, but the explicitly pro-slavery party has more than doubled its delegation. Part of the reason for this is that although the northern states are free from slavery, they aren’t free from racism. There are a lot of people from Maine to Illinois who don’t want blacks as slaves, but would rather not have them as neighbors either.

This attitude has gone west with the northern settlers. Despite the best efforts of President Sergeant and his cabinet, the territorial government of Ioway has forbidden further black settlement after the end of 1835. Mennisota has done the same thing, but has made an exception for those moving to the Zoar[8] area—working, growing ports are just too useful in an underdeveloped area. Kaw-Osage Territory has limited black settlement to three communities, Freedmansville, Jericho and Wrightsburg[9]. And the newest territory, Astoria Territory[10], has entirely forbidden nonwhite settlement—which is particularly unfortunate as this is the territory that comprises the entirety of the U.S.’s Pacific coast.[11]

One of the local leaders of Astoria Territory is Stephen Austin. Although he was one of the settlers who worked to being slavery into Arkansaw in the ‘20s, he’s always been of two minds about the institution. On the one hand, it’s made him a lot of money. On the other hand, he’s really scared of black people. (I said he was of two minds. I didn’t say either one was any help.)

For him, Savannah changed everything. It convinced him that the South, and much of the north, was doomed—servile insurrection and vengeance would one day destroy American civilization. He decided that there had to be at least one territory to serve as a safe space for white people, come the day. (Yes, Astoria already has nonwhite people in it—people who were in fact here first—but Austin doesn’t plan on those people staying there.)

Of course, at this point there aren’t even that many white settlers that far west, especially with so much land suddenly so cheap east of the Mississippi. Those that do come most often come by sea to Fort Clatsop and up the Columbia to Symmes’ Landing,[12] even though this means sailing clear around the tip of South America. Various explorers (including Austin himself) have mapped out a usable overland trail, which people are now calling the Astoria Trail. But even for traders, let alone prospective farmers or settlers with families, this is a very hard road—especially at this early stage. Stockades for protection are few and far between, if your wagon breaks down you have to fix it yourself, if an ox breaks down you can’t even do that much, there’s rivers to cross, measles, dysentery, food shortages, bad weather, inadequate water and grazing, snakebite, dysentery, and for some reason if you shoot a 900-kg bison you’re only allowed to bring 45 kg of meat back to the wagon. Okay, not really, but it’s still a hard, hard road, and if you’re planning to travel it you’d better buy as many supplies as you can right at the start. Ironically enough, the trail happens to begin in Freedmansville, as far up the Missouri as a steamboat can go—so in a small way, the black community will see some benefit from it in years to come. But in the meantime, it’s clear to most that if blacks are to be free and live free in America, most of them will have to do so right where they are. Kyantine is only so large.

Seeing the mighty Dead Roses brought low (or at least medium height) has got some people dreaming big. One of the most important men in the mill town of Alpheus, Georgia is Mirabeau Lamar, publisher of the

Alpheus Enquirer, head of the local Tertium Quid party and correspondent and confidante of the governor. Despite having these responsibilities, and being a widower with a 7-year-old daughter, he’s taken in his nephew and nieces, 10-year-old twins Marcella and Lucius Jr.[13] and their 6-year-old sister Aelia. Their own mother died giving birth to Aelia, and of course their father, Judge Lamar, died in the Savannah Fire. The good news is Uncle Mirabeau is treating the three Lamar orphans with great kindness, and isn’t devising any elaborate plans to steal their fortune. His plans have much larger goals. That’s the bad news.

And the

really bad news is north of Alpheus, in the mountains of Georgia. Last year, gold was discovered, and this year they’ve found that some of it is on Cherokee land. The urge by Governor Berrien and his supporters to dispossess the Cherokee of whatever territory they still possess within the state has gotten that much stronger. Men are (off the books) disappearing from the Cherokee regiments on the Alabama coast so they can go north to protect their families. This is a headache for Secretary of War Benton. As a proponent of westward expansion, he tends to see Native Americans as an obstruction to be cleared aside, but he knows damn well you can’t ask men to guard a nation whose citizens are driving their women and children out of their homes.

Out west, of course, it’s a different story. The tribes in what is now Ioway Territory have been broken. The Quapaw who once lived in Arkansas have been driven west beyond Kyantine, except for a remnant of women, children and the elderly and wounded who couldn’t move that far and are now farming a bit of land near the junction of the Arkansas and Verdigris alongside a company of ex-SINC slaves. The rest of them have invaded the lands of the Kiowa and Witchita. Their allies in this war are the Kaw and Osage, who can see the writing on the wall and are beginning to realize they won’t be able to stay much longer in what is officially called Kaw-Osage Territory. There are so many white men, and they just

keep coming. If the tribes could just get far enough west, get a breather, trade space for time, build up their strength… it’s a pretty forlorn hope, but it’s what they’ve got.

And this war is brutal and ugly, with women and children being massacred[14]—the main reason the Quapaw left so many of theirs behind in what Kyantinians are now calling Quapawtown[15]. To white men (and, in all honesty, to the black men of Kyantine) it looks like a bunch of savages savagely savaging each other. Don’t mistake this for a justification, but all the tribes involved are hunter-gardeners, subsisting on a mix of wild game and agriculture. It’s the only way they know how to live, and while it is a good healthy lifestyle that comes with a protein-rich diet and lots of exercise, it has no margin for error—the buffalo herds aren’t getting any larger, and in this dry climate you can’t just plant a few extra fields of corn and beans if you want to feed a whole bunch of new neighbors. Everyone involved thinks of this as an existential conflict, and so desperate are the Kiowa and Witchita that they’ve called on the Comanche for assistance—something normally no one ever does. (The Comanche have their own problems which will be discussed later.)

In western Mennisota Territory, nobody’s looking too hard at the Dakota, and they don’t mind one bit. Their biggest problem right now is an

absence of white men—specifically trappers, who used to bring steel knives and other useful things to trade with, but who, like their Canadian counterparts, can’t stay in business in this economy. The Dakota themselves aren’t making much from trapping either, although they’re better off than their former enemies the Ojibwe since they at least can find more than one buyer.

Back east, just when the dust was beginning to settle from the midterms, the Supreme Court issued its last decision of 1834, and it was a doozy. It ruled against Ohio in the border dispute

State of Ohio v. Michigan Territory, which means Ohio has to cede the northwestern sliver of land called the Miami Strip[16], a strip of land that will be valuable if the canal-building business ever starts up again. (One of the canal projects that Sergeant’s group decided to abandon was the Miami and Erie Canal[17], from Cincinnati to Miami.)

The one bit of comfort that Ohioans are taking from this is that Miami is the headquarters of a strange new religious movement[18], currently called the Restored Church of Christ (it’s gone through some name changes already) which outsiders generally call the Cumorists, because one of their first publications was a flyer announcing the finding of holy artifacts at some place called “Hill Cumorah.” Officially, the Cumorists (and whatever it is Nat Turner is doing out in Kyantine) are not a problem—religious toleration is the law of the land by virtue of the First Amendment. Unofficially, in most parts of the U.S. even the Catholic Church is seen as strange, foreign, and vaguely threatening.[19] And the Catholic Church is very, very old. The Cumorists are a new thing under the sun, and people really don’t know what to make of them.

Preoccupied with other matters is Captain Sydney Smith Lee of Norfolk, Virginia. His ship is the

USS Representation. and its adventures are as exciting as its name. The last and most seaworthy demologos ever built—which is not saying much—this summer she undertook an epic 180-km voyage to Sinepuxent, Maryland, and then another one back again. This was as much as the Navy could afford. Demologoi burn a lot of coal. The rest of the year was spent in dock, keeping the paint in good condition so the iron-plated hull didn’t rust.

So the 32-year-old Captain Lee has a lot of time on his hands. He uses it to keep in touch with the unofficial head of the family, his older brother Charles Carter Lee, who manages the various estates and is trying to decide if they’ll need to free any of the children of their childbearing slaves for the tax benefit. And of course there’s their kid brother Robert, who’s been having a rough time of it—he had to go through the whole canal commission fiasco while mourning his wife, Mary Anna Randolph Custis, who died two years ago giving birth to a daughter, Martha Mary Custis Lee. One sore point with the family is the loss of Stratford Hall Plantation, which was in the hands of their half-brother Henry and was lost due to his affairs and ill-advised financial dealings. Now it’s owned by a Marylander, former governor Thomas King Carroll, whose 19-year-old daughter Anna Ella is possibly the most outspoken abolitionist in Virginia. Embarrassing.

Speaking of 19-year-olds, up in Martinsburg, Crawford Long is working for Stabler & Sons, trying to earn enough money to finish getting his medical degree. He’s still in correspondence with his old friend from Franklin College, Alex Stephens[20], who’s currently in Britain and complaining about how awful it is there. Long figures it can’t be that bad over there—Alex always was a bit of a whiner. Anyway, there isn’t much for him to say in response, since he can’t talk about the work he’s doing now—it’s as top-secret as anything in the early 19th century can be. And because of the stuff he’s working with, he doesn’t have a lot of attention to spare. One mistake could leave him dead or horribly mutilated.

But in this economy, anybody who has a well-paying job has no reason to complain.

[1] IOTL Henry Poe died in 1831, so he’s still ahead of the game.

[2] I’m not trying to get him cancelled or anything, but IOTL she was his 13-year-old cousin.

[3] Cotton took a similar fall in the 1837 depression IOTL.

[4] He tried this IOTL too.

[5] IOTL, the first state to default was the newest state, Michigan.

[6] This is a direct quote of something Governor McNutt said IOTL about Nathan Rothschild’s son Lionel in 1841.

[7] IOTL he was elected governor as a member of the Anti-Masonic Party.

[8] Duluth, MN and Superior, WI

[9] OTL Independence, MO, Joplin, MO and Moran, KS, respectively. Jericho was founded by an escaped slave from New York State (back when it still had slavery) named Sojourner Truth, formerly known as Isabella Baumfree. Wrightsburg is named for Benjamin Wright, Clay’s Secretary of Domestic Affairs.

[10] So named to distinguish itself from British Oregon to the north.

[11] This was also true of Oregon Territory IOTL.

[12] OTL Portland

[13] Allohistorical brother of OTL’s L.Q.C. Lamar Jr.

[14]

This sort of thing happened IOTL as well.

[15] OTL Muskogee

[16] IOTL the Toledo Strip. Note that the stronger position of the federal government vis-a-vis the states means that state governments are willing to see this sort of dispute resolved by something other than force.

[17] IOTL this canal

was built, but eventually declined.

[18] At this point IOTL, the church that would later be named the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints was headquartered in Kirtland, Ohio.

[19] This is much, much better than

the situation IOTL. It helps that TTL’s Catholic Church is a little more liberal, and the U.S.’s biggest allies are Catholics. It might also help a little that those Catholics who are not at all liberal in their views are more likely to go to Lima.

[20] They were roommates IOTL.