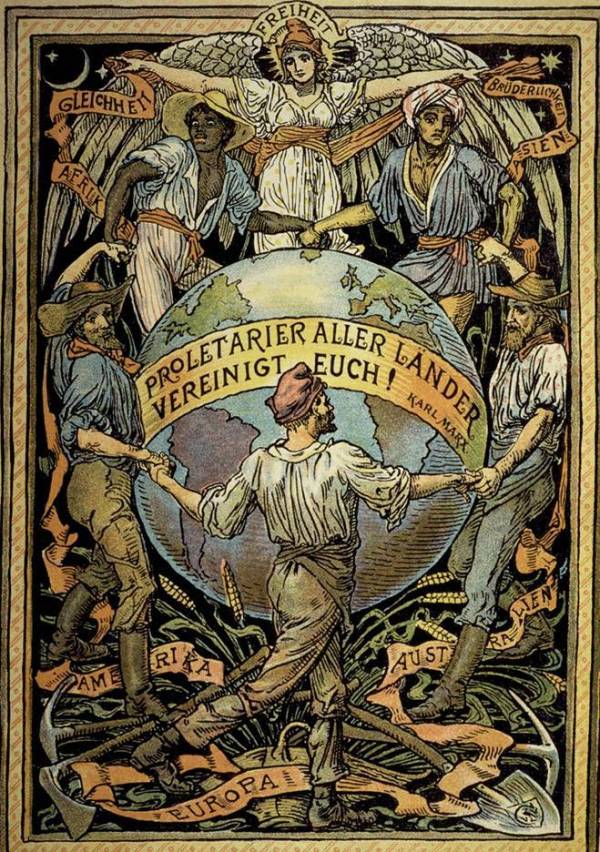

Diamonds in the rough: South Africa and India beyond 1848

Diamonds in the rough

South Africa and India beyond 1848

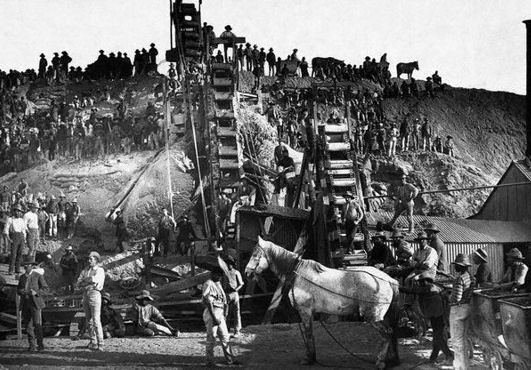

A mining operation in the Cape Free State

A mining operation in the Cape Free State

South Africa and India beyond 1848

"Remnants: A comprehensive history of the British successor states" by Darien Tremblay (2005, Toronto Books)

The collapse of the British Empire, perhaps one of the largest empires of all time, had lasting repercussions. Beyond simply making overseas colonialism seem like somewhat of a white elephant and “old-fashioned”, the Empire left small outposts everywhere in the wake of its collapse. Some retained some contact with their former overlords, such as the many American possessions of the government-in-exile or the explicitly chartist republic of Sierra Leone an even larger number went their own way or were subsumed by their neighbours completely. The most prominent of the states that survived the collapse were the Cape Free State and the parts of the Indian continent still under the nominal control of the EIC (more commonly known both then and now as “the Bandit Coast”).

The image of these states as a lawless no-man’s land full of bandits and ne’er do wells fighting rugged adventurers and scoundrels from the crime-ridden capital seeking fame and fortune is mostly an invention by Eastern movies, but like most fiction there is some amount of truth to it. Crime and corruption was a major issue in both the Cape and Bandit coast, but these took the forms of syndicates, protection rackets, gangs or other criminal organizations rather than lone gun-toting villains. Both states served as a safe haven for a fair number of political dissidents, adventurers, escaped criminals and other unusual members of European society, but the vast majority of European immigrants were (in the case of the Cape) miners looking for gold and diamonds or enterprising merchants looking to profit off of the shipping industry and in the case of the Bandit coast, from the lucrative trade of spices and narcotics (particularly opium).

A scene from the famous Eastern "A fistful of Diamonds" with Clint Eastwood in his signature role.

The Cape Free State in particular was much more “civilized” than the popular imagination would have one believe, with a functioning system of supply trains and lines of communication operating between mining sites and the coastal area of heavy settlement. Most large mines were controlled by either the Cape authorities, a miner’s association or a criminal organization and mining was therefore mostly without risk from outside attackers, though casualties from accidents and the glaring lack of any form of safety standards or regulation were frequent. The only time bandits and wild animals posed real danger was when foolhardy miners or enterprising farmers ventured away from the established mines or roads and tried to start their own operation and even then it was far more common to die of disease or animals like snakes than to be ambushed by gun-toting bandits. Governance of the free state did in fact often fluctuate between local families, groups of business owners and crime lords, but the presence of a population where the vast majority possessed some form of firearm or other weapon meant that these groups often had to consider the interest of the local populace regardless and was often extremely wary of armed uprisings, meaning that a basic system of public health and bans on practices such as slavery and child labour remained in effect even long after formal independence.

The situation on the Pirate coast was often rather different and the vast majority of settlements were often governed by the local populace or a council of elders, but the presence of groups of mercenaries and criminal gangs (in particular those related to the opium trade) did have a large impact on local governance. Many cities hired mercenary units to wage wars against their enemies like the Italian states of the renaissance or aligned themselves with native warlords, fighting over access to the many trade routes both on sea and land, engaging in banditry and robbery when given the opportunity. It should be noted that women on the Bandit coast enjoyed a unique position of relative power compared to many of their contemporaries on the continent, which would become a lasting legacy of female autonomy even as the area was incorporated into neighbouring states and empires. Another pervasive and perhaps somewhat insidious view of the Pirate coast is the inflated presence given to Europeans in most mainstream depictions of the period. In reality there were still of course Anglo-European mercenary units and a small population that remained in the aftermath of the British withdrawal, but the vast majority of powerbrokers, merchants and adventurers of any kind were native Indians who in turn fought for power and money against other Indians, with the presence of Europeans outside the port cities being an exception rather than the rule.