Sarawak's pre-war makeup (1/2)

Bethel Masaro, A Land Transformed: Sarawak and the Great War, (Sandakan University Press: 1990)

It is not an exaggeration to say that the Great War changed many things within the land of the White Rajahs. Aside from Aceh, the state of Sarawak was the only other independent nation in Sundaland that became fully involved in the global conflagration, fielding men, materials, and even logistics to the Bornean and Indochinese fronts. But to truly understand the nation and how it transformed during this brief period, it is worth examining the state that existed prior to the conflict.

When Charles Brooke signed the declaration of war against the Italian Empire, Sarawak was on a slow, yet uneven, process of development. A circuit of the nation, counter-clockwise, reveals clear how the Brooke family had developed the nation, and to what extent…

Natuna and Anambas Islands

If a traveller journeys to Kuching from Bangkok, he or she would first pass through the most distant and fragmented reaches of the Sarawakian state: the Natuna and Anambas archipelago. Ranging from sandbars to kilometre-high peaks, these groups of islands in the middle of the South China Sea were handed to Sarawak following a series of tripartite agreements with the British Empire and the Dutch East Indies, in which every stakeholder would divide the Sundaland region to prevent potential newcomers from nabbing claimed lands.

With their relative position within the South China Sea, the islands had become important waypoints for ships passing through to the ports of East Asia. Realising this, the state has made the region a repeated cruising ground for their blue-water navy, and a small Sarawakian base was even constructed at Natuna Besar island in 1897 to oversee the flow of open trade. Still, the archipelago by 1905 was perhaps the most undeveloped of the Sarawakian regions, receiving the lowest in state funds and investments from the capital. With their vast expanses limiting governmental oversight, it seemed wasteful for the Rajah’s Supreme Council to dump money to uplift the islands and its disparate population, especially with more rewarding projects closer to home.

Fortunately, the islanders took care of that for themselves. Once home to Malay and Chinese fishermen, the archipelago received an influx of thousands of Sama-Bajau newcomers over last two decades. Almost all of them hail from the coasts of Sabah, where Italian rule had resulted in the “Sea Gypsies” being viewed as miscreants and troublemakers, and of aiding rebellious figures. Kicked out of their former seas, many of them headed southwest, where Charles Brooke offered them a new home in the lightly-peopled archipelago. Simultaneously, the rise of the mercantile Dayak class has resulted in several of them becoming peddlers and traders in their own right [1], transporting salt, spices, fish, and light goods across Sarawak to West Borneo, Singapore, and the Malay Peninsula.

Along the way, the peoples of the sea began using their accumulated wealth to uplift themselves and develop their surroundings. Water-villages began to form in protected coasts and bays, followed by ramshackle ports where various trades – legal and otherwise – could be conducted without official oversight. Boatbuilding grew and became a sizable cottage industry by the eve of the War, propelled by the influx of trade and of new families wanting their own homes to roam the seas and shores. Intermarriages between the Malay and Chinese fisherfolk were also seen, though such affairs were uncommon due to differing cultures and lifestyles.

While the Natuna and Anambas islands retained their picture-postcard look to outsiders, the local reality was that of social and economic change, all amidst the azure sea and sky…

Bau and Lundu (Upper Sarawak)

Stretching from Datu Point to the mountains of Matang, this was the region that gave the Kingdom of Sarawak initial wealth and success. Despite being given the odd title of “Upper Sarawak” by the government (despite over 95% of the country bring more northerly than it), the western region’s antimony and quicksilver mines was what propped up the state during its darkest and most trying periods.

However, almost all the valuable ores were thoroughly mined by 1905, with gold production being the only industry that was left running. In fact, gold deposits were still found in profitable quantities across Upper Sarawak, yet the ore grade was low and required heavy treatment using the ‘cyanide process’, where crushed rock is mixed with a solution of calcium cyanide to extract gold particles. Run commercially by the government-linked Borneo Company Ltd, gold mining was a money-maker for the state, though it weren’t enough to employ the tens of thousands of Chinese labourers whom had once worked the mountains. While many migrated, many more began cultivating pepper and gambir farms, sponsored in part by the Sarawak government’s own Kangchu system where spice planters were given subsides in growing and harvesting profitable cash crops.

The extractive nature of the place also influenced local society. While the Chinese workers did not displace the Malay and the Bidayuh subgroup whom call Upper Sarawak home, they did make themselves known in notoriety though their formation of gangs called kongsi. Such societies were a constant bane to the local government as their activities often erred to the disruptive and law-breaking, such as opium selling and illegal gambling. Still, there was a measure of separate coexistence acknowledged among the locals so long as each group stayed out of everyone else’s affairs. The Chinese were also valued as shopkeepers and traders, though their primacy in that respect was in the midst of contention with the rising Iban-Bajau peddling web.

Intriguingly, the region also held a sizable minority of Chinese and Dayak Christians due to a long missionary presence dating back to the founding of Sarawak. The towns of Bau and Lundu were marked as one of the few places where open proselytization was allowed, and the allowing for the formation of a regional Protestant minority. While cultural differences prevented both groups from interacting closely in 1905, there were several instances where Chinese men would abandon their towns and marry into a Bidayuh longhouse or even a Malay village, the dearth of ethnic wives being a strong motivator to cross the cultural and (sometimes) religious gulf. The relative peace of the region after decades of pirate raids have also influenced local subgroups to build their communities on lower ground, instead of on steep hillsides and hill-tops as it were in the 1840s.

For its mineral and agricultural value, Upper Sarawak was often the most invested by Kuching in the preceding decades. Roads, docks, telegraph cables, and basic services are often implemented here first before being applied to the rest of the nation, though much of these were mostly done in the service of resource extraction than anything else. Nevertheless, a number of local hamlets and buildings still mark their existence to the fortune of the earth…

Kuching and the South-East Rivers

With its population of over 120,000 inhabitants, it could be said that Kuching was one of the largest (if not, the largest) urban centre in all Borneo by the eve of the War. Fifty-nine years of Brooke rule had seen the fishing hamlet turned into a prosperous administrative and commercial capital, where forest peoples jostled with traders and civil servants amidst the rambling shophouses and ferry boats.

While the capital paled in comparison to British Singapore or Dutch Batavia, Kuching possessed several notable features rare and even alien to Borneo for the time such as a sewerage system, dry docks, fully-fledged embassies, and even an anthropological museum. Its hut schools saw the primary education of local Malays while the Astana played host to a small women’s literary scene under Margaret Brooke’s tutelage, as the local writer Siti Sahada showed with her authoring of the Sarawak Annals. Missionaries fanned out from the city to the mountains that lay to the south, converting the Bidayuh tribes nestling along the Dutch border.

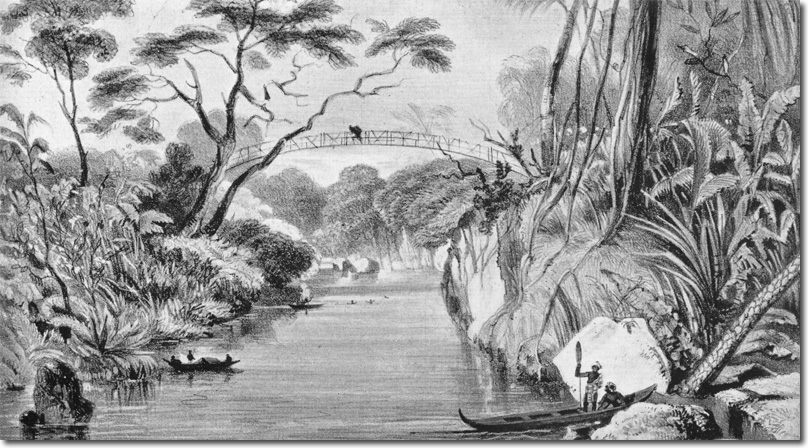

But of equal value lay the great rivers that lay to the east of the city. Great rivers in Sarawak are named “Batang” in the local tongue, and the Sadong, Lupar, Saribas, and Krian waterways were seen as such by all who lived there. Aside from the powerful currents and the lunar tide bores, it was these rivers that allowed the Iban peoples to head downriver and pillage the Bornean coasts. By 1905, the piracy era has long since passed, but several Iban chieftains began utilising their voyaging skills to new use with the times. The advent of Sarawak had also brought a rise in trade, and several chiefs began capitalising on this by embarking to Singapore in the 1890’s to gain precious porcelain jars for their longhouses. [2] On the holds of local war prahus, the value of trade swiftly spread.

By the eve of the War, a network of peddlers and small-time merchants had coalesced amongst the reaches of the Batang Lupar and Batang Krian. Through careful kinship links and the inclusion of the seaborne Sama-Bajau, a trade web had formed that linked southern Malaya and western Borneo to the riverine region. Pots, pans, and precious items from Singapore and Dutch Borneo were traded for forestry products, local pepper, and cheap Sarawak salt. Given the low purchasing power of the locals and the overall value of goods, these Iban and Bajau merchants were no match for their large and multinational Chinese counterparts, much less the rich and influential Peranakan class of all Sundaland. Nonetheless, their inexpensive wares coupled with penetration into rainforest regions offered a new occupation to tribal communities, with potentially great rewards.

And as with the Natuna and Anambas islands, it was these traders that spearheaded the development of the south-southeastern rivers. While Kuching had built forts and docks in the preceding decades to patrol the once-restive rivers, it was the Orang Dagang – the Trade People, as they called themselves – whom began to invest in substantial works such as warehouses and bamboo bridges. For ease of access, dirt roads were hacked into the degraded forest (for the gutta-percha craze had affected the region badly), stretching all the way from riverine Saratok to the Dutch border at Lubok Antu, at the geographic edge of the Sentarum floodplains.

While not up to par with the services of Upper Sarawak, the Batang region was changing on the backs of its residents…

The Rajang and Mukah

From the streams trickling down the high slopes of the Iran Mountains, the mighty Batang Rajang served many as it courses into central Sarawak. During the heyday of the Bruneian Empire, the mouth of the watercourse was fortified to allow officials gather taxes from the flow of people and trade to and from the interior. By 1905, the practice has been relegated to history, though the Sarawakian forts that dot its banks speak of the river’s potential to transport rebellion.

For the Kuching government, the river was a vital highway into the heart of Borneo and was thus placed second to none in matters of defence. In 1900, all riverside forts were upgraded with new weaponry while upstream longhouse villages were enticed to move downriver as a precautionary measure against revolt. Further downstream, the Chinese Methodist community of Sibu swelled with the influx of foreign refugees, planting the region’s future as both a regional trade hub and a bastion of Methodist Christianity. The townsfolk’s agreement with Charles Brooke to plant gutta-percha trees were also conducted in full swing at this time, paving the way for the Rajang’s mouth as an important wartime source of rubber.

In the immediate north, the Melanau homeland of the Mukah region was also a changed land. The era of internecine and piratical warfare was long over, and newly-built village tallhouses began to shed their defensive capabilities as a result. Once renowned for their tall and fortress-like communal dwellings, the Melanau began to build looser and more open superstructures by the early 1900s, with large verandas and open corridors, though the propensity of river floods often force their new constructions to be built on pillars as high as forty feet off the ground.

Socially and economically, the subgroup has slowly began to branch itself out from traditional occupations, though not to the extent of their Iban and Sama-Bajau neighbours. While farming, fishing, and sago harvesting dominated local life, a few trade links were established with the nearby Chinese and native traders, and a fair few youngsters have boarded the kingdom’s many gunboats to be employed as native crews. Later on, it would be these trained and experienced men whom will truly change Melanau society…

Bintulu and Niah

If there was a place where development forgot, it would be the Bintulu and Niah rivers.

Sandwiched between the Rajang to the south and the Baram to the north, the basins of Bintulu and Niah could be described as the backwater of Sarawak in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Although taking up a sizable part of the kingdom, there was little of interest here to the Brookes, the government, or the enterprising peoples to warrant any sort of exploitation or social development as in other places. Indeed, what little value these lands have to Kuching lay in preventing any Dayak raids that could threaten the oil-rich north or the commercial south.

For the government, that meant a series of forts and docks, and not much else. For the local tribes, that meant unyielding oversight by their new authorities, along with necessary obedience to the new anti-headhunting and anti-slavery laws. For the local Malays and a few Chinese residents, it meant paying taxes to an eclectic Resident-Councillor system. Still, an account from the Resident of Bintulu town in 1899 described how governmental establishment meant little for local dynamism, stating:

“…The main street of Bintulu possesses only 20 shophouses, all of which are shabbily built and mainly constructed out of local woods topped with nipah fronds. The nearest kampong (village) adds just 3 more structures, and the Government Office is worked by a measly staff of four, myself included. The Dyaks living near the town have changed little in their ways, with the only notable exception being the conversion of a local tribe called “Sagan” to Mohammadanism several decades back. Otherwise, little has changed here since the inclusion of the land into the Brooke Raj.”

In this, however, the Resident was wrong. Over the past twelve years, a series of irregular migrations have been underway by the southern Iban and Melanau tribes into the northern interior. The relative stability of the lowlands near Kuching and the Rajang have resulted in degraded forests and depleted soils, a problem that was exacerbated by the gutta-percha scramble. Thus, under the authorization of Charles Brooke, several longhouses under the leadership of the pioneer Iban chieftain, Penghulu Jelani anak Rekan, began to migrate north. Over time, a stream of Iban and Melanau peoples would join them.

The entry of the southern newcomers weren’t accepted with open arms by the local peoples. Despite the abundance of land, rivers, and coasts, the tribes of Bintulu and Niah sought legal recourse for their earthen holdings, travelling constantly to Kuching in the hopes of receiving arbitration from the government. By the eve of the Great War, the region simmered of discontent…

Miri and the Baram River

By contrast, the fishing village of Miri attained a new rough-and-tumble character as became a hub for both the nascent petroleum industry and a refuelling station for the British and Austro-Hungarian navies, though it was mostly the British that used Miri as a base.

The increased attention of the village brought new changes that completely overturned the character of Miri. The Oil Policy agreement of 1898 turned the village into an autonomous enclave where foreign companies ruled the roost, but the challenges of building a new industry in a tropical environment vexed even the most powerful of corporations. New cable-tool drills were needed to extract petroleum, and that meant building entirely new facilities for the endeavour; There were swamps that needed filling, forests that needed felling, roads that needed building, and docks that needed manning, and all with a dearth of skilled workers to go around.

The result was a Miri that was completely opposite the form of most Sarawakian urban centres. Travellers visiting the town in the 1900’s spoke of a place that looked half-finished, dirty, and swarming with foreigners. In place of a mélange of races inhabiting around ethnic centres, the town became informally segregated around race and wealth; European overseers staked their homes near Miri Hill while the Malays and established Chinese lived in the town centre by the riverbanks. Given the Oil Policy’s stipulation that Malays and Dayaks be freed from work, a new stream of imported Chinese labour began streaming into Miri, most of whom were enticed with promises of high pay for squalid conditions. Living in segregated workers quarters, these coolies were seen with distaste by the locals and even their Chinese mercantile counterparts for being uncouth and unadapting, a sentiment that, in a strange twist, was equally shared by the oil overseers.

Further inland, the landscape turned into the typical Bornean interior rainforest with the Kenyah, Punan, and Lun Bawang subgroups holding sway under the deep canopies. But the situation here is much different than in Bintulu, for the Batang Baram snakes close to the borders of Italian-protected Brunei. Exploiting the tribal migrations and the arrival of the Orang Itali, Charles Brooke had instructed loyal Iban tribes to settle close to the border, ensuring a constant observance on suspicious activities beyond the border. A separate Government Office was built in the town of Kuala Baram to oversee interior operations, and it was this office that gave the word that Bruneian border defences were light in 1905…

Kinabalu / Western Sabah / the Sarawakian Far North

Stretching from Brunei’s northern border to the shores of Kudat Bay, the region of Western Sabah is the northernmost reach of Brooke rule in mainland Borneo, though its separation from the kingdom by Brunei led the region to be greatly influenced by its distance from the political centre and by the neighbours that share its borders.

Administratively named as the Kinabalu Division, the sheer distance and separation from Kuching meant that local autonomy was a given for the far north. Far more than forts, docks, or roads, the Brooke family counted more on diplomacy to keep the area under their influence, promising guarantees of cultural autonomy and customary laws to the coastal towns that were led by ex-Bruneian families, all in exchange for levying local men for the White Rajahs and bending the knee to faraway Kuching. Given the nature of her Italian neighbours, it was a pragmatic policy, though it also led to the continuance of dynastic politics that obstructs the region to this day.

For the interior, the Murut, Kadazan, and Rungus peoples were enticed with freedom and stability so long as they bent the knee and obeyed the law, which was accepted though with some apprehension. This was actually aided by Italian Sabah’s actions across the border, with their exploitation of human labour and forceful conversions pushing a number of tribes to migrate westwards for protection. While this did result in a spate of tribal warfare as the displaced peoples sought new ground, ironically, Sandakan’s consolidation formed a convenient excuse for Rajah Charles to present himself as a peaceful arbiter to the local inhabitants, so long as they toed the line in slavery and headhunting.

Infrastructurally, the sheer distance of the far north and the presence of a distrustful neighbour lent to some measure of local development, especially for the coastal towns which swelled into trade centres for the region and beyond. Bandar Charles in particular grew into a prosperous entrepôt for its unique position to the Spanish Philippines (the ports of Zamboanga and Puerto Princessa are actually closer to it than Kuching). The region had even attracted a few members of the Iban-Bajau trade web by 1904, with the latter subgroup making inroads among the sea nomads whom stayed north, setting the stage for intra-regional indigenous trade in the following years.

With relative peace and commercial exchange, it is no surprise that cultural mixing followed. Besides the unusual contingent of Chinese and Dayak merchants, there were actually a few Filipinos residing on the coasts as traders, though their numbers are miniscule compared to the populous crop of labourers employed by Sandakan next door. The uptick in trade also allowed new faiths to spread inland, and it wasn’t long before both Protestant denominations and syncretic Islam began to creep into the rainforests, spread along by Chinese, Malay, and Dayak peddlers. As in the rest of Sarawak, these new converts were small in number, yet they also reflect a broader trend emblematic of Sarawak and contemporary Borneo: of the outside world immersing itself into tribal society.

And in a strange twist of fate, it would be a combination of all of the above – the orientation of the region to Sarawak, the trade web of the locals and foreigners, and the creep of alternate faiths – that would lead to the rending of Sabah’s indigenous affiliations, and plant the seed that would end notions of Kadazan-Dusun unity…

____________________

Notes:

1. and 2.) See posts #922 and #1057 to see the beginnings of the Dayak-Bajau trade web.

It is not an exaggeration to say that the Great War changed many things within the land of the White Rajahs. Aside from Aceh, the state of Sarawak was the only other independent nation in Sundaland that became fully involved in the global conflagration, fielding men, materials, and even logistics to the Bornean and Indochinese fronts. But to truly understand the nation and how it transformed during this brief period, it is worth examining the state that existed prior to the conflict.

When Charles Brooke signed the declaration of war against the Italian Empire, Sarawak was on a slow, yet uneven, process of development. A circuit of the nation, counter-clockwise, reveals clear how the Brooke family had developed the nation, and to what extent…

Natuna and Anambas Islands

If a traveller journeys to Kuching from Bangkok, he or she would first pass through the most distant and fragmented reaches of the Sarawakian state: the Natuna and Anambas archipelago. Ranging from sandbars to kilometre-high peaks, these groups of islands in the middle of the South China Sea were handed to Sarawak following a series of tripartite agreements with the British Empire and the Dutch East Indies, in which every stakeholder would divide the Sundaland region to prevent potential newcomers from nabbing claimed lands.

With their relative position within the South China Sea, the islands had become important waypoints for ships passing through to the ports of East Asia. Realising this, the state has made the region a repeated cruising ground for their blue-water navy, and a small Sarawakian base was even constructed at Natuna Besar island in 1897 to oversee the flow of open trade. Still, the archipelago by 1905 was perhaps the most undeveloped of the Sarawakian regions, receiving the lowest in state funds and investments from the capital. With their vast expanses limiting governmental oversight, it seemed wasteful for the Rajah’s Supreme Council to dump money to uplift the islands and its disparate population, especially with more rewarding projects closer to home.

Fortunately, the islanders took care of that for themselves. Once home to Malay and Chinese fishermen, the archipelago received an influx of thousands of Sama-Bajau newcomers over last two decades. Almost all of them hail from the coasts of Sabah, where Italian rule had resulted in the “Sea Gypsies” being viewed as miscreants and troublemakers, and of aiding rebellious figures. Kicked out of their former seas, many of them headed southwest, where Charles Brooke offered them a new home in the lightly-peopled archipelago. Simultaneously, the rise of the mercantile Dayak class has resulted in several of them becoming peddlers and traders in their own right [1], transporting salt, spices, fish, and light goods across Sarawak to West Borneo, Singapore, and the Malay Peninsula.

Along the way, the peoples of the sea began using their accumulated wealth to uplift themselves and develop their surroundings. Water-villages began to form in protected coasts and bays, followed by ramshackle ports where various trades – legal and otherwise – could be conducted without official oversight. Boatbuilding grew and became a sizable cottage industry by the eve of the War, propelled by the influx of trade and of new families wanting their own homes to roam the seas and shores. Intermarriages between the Malay and Chinese fisherfolk were also seen, though such affairs were uncommon due to differing cultures and lifestyles.

While the Natuna and Anambas islands retained their picture-postcard look to outsiders, the local reality was that of social and economic change, all amidst the azure sea and sky…

Bau and Lundu (Upper Sarawak)

Stretching from Datu Point to the mountains of Matang, this was the region that gave the Kingdom of Sarawak initial wealth and success. Despite being given the odd title of “Upper Sarawak” by the government (despite over 95% of the country bring more northerly than it), the western region’s antimony and quicksilver mines was what propped up the state during its darkest and most trying periods.

However, almost all the valuable ores were thoroughly mined by 1905, with gold production being the only industry that was left running. In fact, gold deposits were still found in profitable quantities across Upper Sarawak, yet the ore grade was low and required heavy treatment using the ‘cyanide process’, where crushed rock is mixed with a solution of calcium cyanide to extract gold particles. Run commercially by the government-linked Borneo Company Ltd, gold mining was a money-maker for the state, though it weren’t enough to employ the tens of thousands of Chinese labourers whom had once worked the mountains. While many migrated, many more began cultivating pepper and gambir farms, sponsored in part by the Sarawak government’s own Kangchu system where spice planters were given subsides in growing and harvesting profitable cash crops.

The extractive nature of the place also influenced local society. While the Chinese workers did not displace the Malay and the Bidayuh subgroup whom call Upper Sarawak home, they did make themselves known in notoriety though their formation of gangs called kongsi. Such societies were a constant bane to the local government as their activities often erred to the disruptive and law-breaking, such as opium selling and illegal gambling. Still, there was a measure of separate coexistence acknowledged among the locals so long as each group stayed out of everyone else’s affairs. The Chinese were also valued as shopkeepers and traders, though their primacy in that respect was in the midst of contention with the rising Iban-Bajau peddling web.

Intriguingly, the region also held a sizable minority of Chinese and Dayak Christians due to a long missionary presence dating back to the founding of Sarawak. The towns of Bau and Lundu were marked as one of the few places where open proselytization was allowed, and the allowing for the formation of a regional Protestant minority. While cultural differences prevented both groups from interacting closely in 1905, there were several instances where Chinese men would abandon their towns and marry into a Bidayuh longhouse or even a Malay village, the dearth of ethnic wives being a strong motivator to cross the cultural and (sometimes) religious gulf. The relative peace of the region after decades of pirate raids have also influenced local subgroups to build their communities on lower ground, instead of on steep hillsides and hill-tops as it were in the 1840s.

For its mineral and agricultural value, Upper Sarawak was often the most invested by Kuching in the preceding decades. Roads, docks, telegraph cables, and basic services are often implemented here first before being applied to the rest of the nation, though much of these were mostly done in the service of resource extraction than anything else. Nevertheless, a number of local hamlets and buildings still mark their existence to the fortune of the earth…

Kuching and the South-East Rivers

With its population of over 120,000 inhabitants, it could be said that Kuching was one of the largest (if not, the largest) urban centre in all Borneo by the eve of the War. Fifty-nine years of Brooke rule had seen the fishing hamlet turned into a prosperous administrative and commercial capital, where forest peoples jostled with traders and civil servants amidst the rambling shophouses and ferry boats.

While the capital paled in comparison to British Singapore or Dutch Batavia, Kuching possessed several notable features rare and even alien to Borneo for the time such as a sewerage system, dry docks, fully-fledged embassies, and even an anthropological museum. Its hut schools saw the primary education of local Malays while the Astana played host to a small women’s literary scene under Margaret Brooke’s tutelage, as the local writer Siti Sahada showed with her authoring of the Sarawak Annals. Missionaries fanned out from the city to the mountains that lay to the south, converting the Bidayuh tribes nestling along the Dutch border.

But of equal value lay the great rivers that lay to the east of the city. Great rivers in Sarawak are named “Batang” in the local tongue, and the Sadong, Lupar, Saribas, and Krian waterways were seen as such by all who lived there. Aside from the powerful currents and the lunar tide bores, it was these rivers that allowed the Iban peoples to head downriver and pillage the Bornean coasts. By 1905, the piracy era has long since passed, but several Iban chieftains began utilising their voyaging skills to new use with the times. The advent of Sarawak had also brought a rise in trade, and several chiefs began capitalising on this by embarking to Singapore in the 1890’s to gain precious porcelain jars for their longhouses. [2] On the holds of local war prahus, the value of trade swiftly spread.

By the eve of the War, a network of peddlers and small-time merchants had coalesced amongst the reaches of the Batang Lupar and Batang Krian. Through careful kinship links and the inclusion of the seaborne Sama-Bajau, a trade web had formed that linked southern Malaya and western Borneo to the riverine region. Pots, pans, and precious items from Singapore and Dutch Borneo were traded for forestry products, local pepper, and cheap Sarawak salt. Given the low purchasing power of the locals and the overall value of goods, these Iban and Bajau merchants were no match for their large and multinational Chinese counterparts, much less the rich and influential Peranakan class of all Sundaland. Nonetheless, their inexpensive wares coupled with penetration into rainforest regions offered a new occupation to tribal communities, with potentially great rewards.

And as with the Natuna and Anambas islands, it was these traders that spearheaded the development of the south-southeastern rivers. While Kuching had built forts and docks in the preceding decades to patrol the once-restive rivers, it was the Orang Dagang – the Trade People, as they called themselves – whom began to invest in substantial works such as warehouses and bamboo bridges. For ease of access, dirt roads were hacked into the degraded forest (for the gutta-percha craze had affected the region badly), stretching all the way from riverine Saratok to the Dutch border at Lubok Antu, at the geographic edge of the Sentarum floodplains.

While not up to par with the services of Upper Sarawak, the Batang region was changing on the backs of its residents…

The Rajang and Mukah

From the streams trickling down the high slopes of the Iran Mountains, the mighty Batang Rajang served many as it courses into central Sarawak. During the heyday of the Bruneian Empire, the mouth of the watercourse was fortified to allow officials gather taxes from the flow of people and trade to and from the interior. By 1905, the practice has been relegated to history, though the Sarawakian forts that dot its banks speak of the river’s potential to transport rebellion.

For the Kuching government, the river was a vital highway into the heart of Borneo and was thus placed second to none in matters of defence. In 1900, all riverside forts were upgraded with new weaponry while upstream longhouse villages were enticed to move downriver as a precautionary measure against revolt. Further downstream, the Chinese Methodist community of Sibu swelled with the influx of foreign refugees, planting the region’s future as both a regional trade hub and a bastion of Methodist Christianity. The townsfolk’s agreement with Charles Brooke to plant gutta-percha trees were also conducted in full swing at this time, paving the way for the Rajang’s mouth as an important wartime source of rubber.

In the immediate north, the Melanau homeland of the Mukah region was also a changed land. The era of internecine and piratical warfare was long over, and newly-built village tallhouses began to shed their defensive capabilities as a result. Once renowned for their tall and fortress-like communal dwellings, the Melanau began to build looser and more open superstructures by the early 1900s, with large verandas and open corridors, though the propensity of river floods often force their new constructions to be built on pillars as high as forty feet off the ground.

Socially and economically, the subgroup has slowly began to branch itself out from traditional occupations, though not to the extent of their Iban and Sama-Bajau neighbours. While farming, fishing, and sago harvesting dominated local life, a few trade links were established with the nearby Chinese and native traders, and a fair few youngsters have boarded the kingdom’s many gunboats to be employed as native crews. Later on, it would be these trained and experienced men whom will truly change Melanau society…

Bintulu and Niah

If there was a place where development forgot, it would be the Bintulu and Niah rivers.

Sandwiched between the Rajang to the south and the Baram to the north, the basins of Bintulu and Niah could be described as the backwater of Sarawak in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Although taking up a sizable part of the kingdom, there was little of interest here to the Brookes, the government, or the enterprising peoples to warrant any sort of exploitation or social development as in other places. Indeed, what little value these lands have to Kuching lay in preventing any Dayak raids that could threaten the oil-rich north or the commercial south.

For the government, that meant a series of forts and docks, and not much else. For the local tribes, that meant unyielding oversight by their new authorities, along with necessary obedience to the new anti-headhunting and anti-slavery laws. For the local Malays and a few Chinese residents, it meant paying taxes to an eclectic Resident-Councillor system. Still, an account from the Resident of Bintulu town in 1899 described how governmental establishment meant little for local dynamism, stating:

“…The main street of Bintulu possesses only 20 shophouses, all of which are shabbily built and mainly constructed out of local woods topped with nipah fronds. The nearest kampong (village) adds just 3 more structures, and the Government Office is worked by a measly staff of four, myself included. The Dyaks living near the town have changed little in their ways, with the only notable exception being the conversion of a local tribe called “Sagan” to Mohammadanism several decades back. Otherwise, little has changed here since the inclusion of the land into the Brooke Raj.”

In this, however, the Resident was wrong. Over the past twelve years, a series of irregular migrations have been underway by the southern Iban and Melanau tribes into the northern interior. The relative stability of the lowlands near Kuching and the Rajang have resulted in degraded forests and depleted soils, a problem that was exacerbated by the gutta-percha scramble. Thus, under the authorization of Charles Brooke, several longhouses under the leadership of the pioneer Iban chieftain, Penghulu Jelani anak Rekan, began to migrate north. Over time, a stream of Iban and Melanau peoples would join them.

The entry of the southern newcomers weren’t accepted with open arms by the local peoples. Despite the abundance of land, rivers, and coasts, the tribes of Bintulu and Niah sought legal recourse for their earthen holdings, travelling constantly to Kuching in the hopes of receiving arbitration from the government. By the eve of the Great War, the region simmered of discontent…

Miri and the Baram River

By contrast, the fishing village of Miri attained a new rough-and-tumble character as became a hub for both the nascent petroleum industry and a refuelling station for the British and Austro-Hungarian navies, though it was mostly the British that used Miri as a base.

The increased attention of the village brought new changes that completely overturned the character of Miri. The Oil Policy agreement of 1898 turned the village into an autonomous enclave where foreign companies ruled the roost, but the challenges of building a new industry in a tropical environment vexed even the most powerful of corporations. New cable-tool drills were needed to extract petroleum, and that meant building entirely new facilities for the endeavour; There were swamps that needed filling, forests that needed felling, roads that needed building, and docks that needed manning, and all with a dearth of skilled workers to go around.

The result was a Miri that was completely opposite the form of most Sarawakian urban centres. Travellers visiting the town in the 1900’s spoke of a place that looked half-finished, dirty, and swarming with foreigners. In place of a mélange of races inhabiting around ethnic centres, the town became informally segregated around race and wealth; European overseers staked their homes near Miri Hill while the Malays and established Chinese lived in the town centre by the riverbanks. Given the Oil Policy’s stipulation that Malays and Dayaks be freed from work, a new stream of imported Chinese labour began streaming into Miri, most of whom were enticed with promises of high pay for squalid conditions. Living in segregated workers quarters, these coolies were seen with distaste by the locals and even their Chinese mercantile counterparts for being uncouth and unadapting, a sentiment that, in a strange twist, was equally shared by the oil overseers.

Further inland, the landscape turned into the typical Bornean interior rainforest with the Kenyah, Punan, and Lun Bawang subgroups holding sway under the deep canopies. But the situation here is much different than in Bintulu, for the Batang Baram snakes close to the borders of Italian-protected Brunei. Exploiting the tribal migrations and the arrival of the Orang Itali, Charles Brooke had instructed loyal Iban tribes to settle close to the border, ensuring a constant observance on suspicious activities beyond the border. A separate Government Office was built in the town of Kuala Baram to oversee interior operations, and it was this office that gave the word that Bruneian border defences were light in 1905…

Kinabalu / Western Sabah / the Sarawakian Far North

Stretching from Brunei’s northern border to the shores of Kudat Bay, the region of Western Sabah is the northernmost reach of Brooke rule in mainland Borneo, though its separation from the kingdom by Brunei led the region to be greatly influenced by its distance from the political centre and by the neighbours that share its borders.

Administratively named as the Kinabalu Division, the sheer distance and separation from Kuching meant that local autonomy was a given for the far north. Far more than forts, docks, or roads, the Brooke family counted more on diplomacy to keep the area under their influence, promising guarantees of cultural autonomy and customary laws to the coastal towns that were led by ex-Bruneian families, all in exchange for levying local men for the White Rajahs and bending the knee to faraway Kuching. Given the nature of her Italian neighbours, it was a pragmatic policy, though it also led to the continuance of dynastic politics that obstructs the region to this day.

For the interior, the Murut, Kadazan, and Rungus peoples were enticed with freedom and stability so long as they bent the knee and obeyed the law, which was accepted though with some apprehension. This was actually aided by Italian Sabah’s actions across the border, with their exploitation of human labour and forceful conversions pushing a number of tribes to migrate westwards for protection. While this did result in a spate of tribal warfare as the displaced peoples sought new ground, ironically, Sandakan’s consolidation formed a convenient excuse for Rajah Charles to present himself as a peaceful arbiter to the local inhabitants, so long as they toed the line in slavery and headhunting.

Infrastructurally, the sheer distance of the far north and the presence of a distrustful neighbour lent to some measure of local development, especially for the coastal towns which swelled into trade centres for the region and beyond. Bandar Charles in particular grew into a prosperous entrepôt for its unique position to the Spanish Philippines (the ports of Zamboanga and Puerto Princessa are actually closer to it than Kuching). The region had even attracted a few members of the Iban-Bajau trade web by 1904, with the latter subgroup making inroads among the sea nomads whom stayed north, setting the stage for intra-regional indigenous trade in the following years.

With relative peace and commercial exchange, it is no surprise that cultural mixing followed. Besides the unusual contingent of Chinese and Dayak merchants, there were actually a few Filipinos residing on the coasts as traders, though their numbers are miniscule compared to the populous crop of labourers employed by Sandakan next door. The uptick in trade also allowed new faiths to spread inland, and it wasn’t long before both Protestant denominations and syncretic Islam began to creep into the rainforests, spread along by Chinese, Malay, and Dayak peddlers. As in the rest of Sarawak, these new converts were small in number, yet they also reflect a broader trend emblematic of Sarawak and contemporary Borneo: of the outside world immersing itself into tribal society.

And in a strange twist of fate, it would be a combination of all of the above – the orientation of the region to Sarawak, the trade web of the locals and foreigners, and the creep of alternate faiths – that would lead to the rending of Sabah’s indigenous affiliations, and plant the seed that would end notions of Kadazan-Dusun unity…

____________________

Notes:

1. and 2.) See posts #922 and #1057 to see the beginnings of the Dayak-Bajau trade web.