RSR: Democratic Russia (part 1)

Mikhail Nichovsky, ‘

The Rise and Fall of the Bear: A history of Twentieth Century Russia and its impact on the global political scene’ pp. 67-71

With the conflict of the Great War over in 1914, the nation of Russia was left with a mixed deal, and therefore with drastic options. On one hand, they had once again managed to repel the Japanese from their territory, while gaining an even stronger position with regard to China. One the other though, they had not gained any territories from the Japanese this time, just lost many lives, while opening the country to a communist revolt, something even more frightening than the previous imperial government. It had showed that Russian preparation in the Far East was greatly underprepared, as little effort had been made in improving and building Siberian infrastructure, something which would leave their protectorates and satellites vulnerable. They had lost Korea and nearly lost Manchuria to Japanese occupation, with this war being much more intense than the previous one due to the issue of Europe. The rise of a communist power also brought empowerment to radical socialists throughout Russia, particularly the Bolshevik party, a faction of the Social Democratic Labour Party calling for violent revolution against the Tsar. Such a move could not be allowed, and so moves were made to eliminate them as a major faction.

In Europe, the treaty was even bloodier. They had lost many thousands of men, along with Poland, the Baltics, Finland and Bessarabia, mainly to German influence. The rise of this deadly opponent made Russia feel paranoid from such encirclement, even if the two enemies were certainly not allies. The nations that maintained friendliness with them were the French, British, Italians and Americans, who would prefer Russia over either of these two extremes. While free of risk from Polish rebellion, which had been a threat for years before hand, the nation was facing unrest from other minorities.

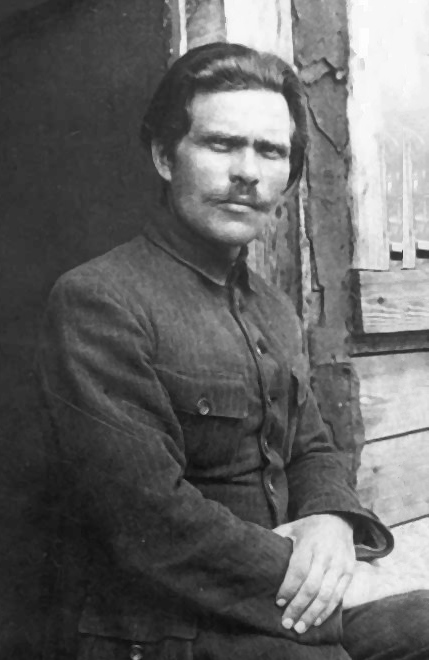

In January 1915, a collaboration of Ukrainian forces gathered in the city of Kiev. They had lost many men fighting the Germans as they advanced into their territory, far more than they would have preferred to lose, often being used as canon fodder by the Russians. The potential for independence was a very tempting offer for these groups. A Ukrainian nation of sorts had already been established by the Germans in Ruthenia, and while it was ideal that they would be independent, it was possible that the ‘Black Council’ as it was known would collaborate secretly with the Germans. Some within the council however opted for different solutions, such as Nestor Makhno, who argued that the Ukrainians should follow the example of Kotoku in Japan, and try and establish a nation independent of not just another power, but any government at all. This split in the council between radicals and moderates made negotiations problematic and resulted to factionalism, the point that it appeared as though a civil war in the Ukraine was on the way even among the rebels. Fortunately, the council was bought together once again following plans from St. Petersburg to encourage Russian settlement in the city were made public. With their way of life threatened, the Black Council organised a large uprising.[1] This would be known throughout history as ‘The Black Winter’.

A picture of the one member of the Black Council to split, Nestor Makhno, who wished to follow the anarchist ways of thinking first established in Nauru and extend it to Europe.

Open Rebellion breaking out in the Ukraine lead the rest of Russia towards a path of increased fear and insecurity. ‘If the Ukrainians could rebel, why couldn’t we?’ was the question many minorities began to think at the news of such rebellion. They were not just secessionists either, but those who wanted a genuine change in the government, a more democratic society, with a Duma that held some level of political power. Protests occurred in the streets to oppose this system. Tsar Nicholas’ plan was to establish a Duma that would only mildly reduce his personal power and allow him to maintain control. However, this was simply not an option available to him. As an incompetent monarch, and one which was losing popularity among the people, a necessary move for the country would be to democratise and modernise with the rest of the world. A powerful Duma would be a necessary step in such a direction by providing the people with a direct way of interacting with the government and thus being able to accommodate their needs, along with help Russia compete on a global level with other powers, something that would be very necessary with such opposing neighbours. It would also appease their allies in Britain and France, who democratised long before and would be welcoming towards Russia making such a move. As a result, Nicholas reluctantly granted the Duma autonomy to control the country in June. The first prime minister of this new nation would be the relatively liberal Alexander Kerensky of the Liberal Party, one of those who was most committed to the liberalisation of the country. While not the most competent of leaders, he was able to rally the duma behind an attack on the uprising in the Ukraine, which would help the nation stay together more. Resources poured into cutting out major rebel strongholds while also seiging the city of Kiev which was under the control of the Council. A Free Territory was attempted establishment by Makhno during September till November, but this was quickly strangled by the Imperial army. Financial support from Britain and France in the conflict certainly helped, though it was dragged on longer as Germany, Turkey and even Japan sent forms of aid to the rebels. As rebellion died down later in the year, the country settled back into peace mode and so the relatively brief era known as the Nicholatian Democracy (1916-1927) began.[2]

In the Far East, the situation was generally more peaceful, as no organised rebellions took place during this period. Part of this was due to the presence of secret police patrolling such places as Manchuria and Mongolia, with mainly military and traders settling in these regions, though some limited settlement did take place over time, particularly in the peripheries of these spaces. In Manchuria, the young Duke Yufeng, former bastion of Manchu independence, was effectively a Russian puppet raised into a position of regency by Russian governers, who would make sure his little nation of origin would not resist Russian assimilation as missionaries and cultural practises found their way into the region, similar to how they had in Outer Manchuria, just at a much slower pace. Others in his family were less malleable to colonial needs and so were often kept away from the former Emperor for "his safety" [3]. Admiral Kolchak was in charge of the Far East’s naval position, while General Semyonov was set to guard Manchuria itself from rebellion, with him garnering an infamous reputation as a result of this. His minion, the ‘Mad Colonel’ Ungern-Sternberg served as his right hand man rooting out dissent within the protectorates.[4] The anti-communist purges were particularly strong here following the conclusion of the Japanese revolution, and the Explusion act of Summer 1917 officially led to hundreds of Manchurian communists fleeing the country or being killed. Unofficially however, many merely moved underground instead and found more discreet ways to meet, while often sabotaging imperial efforts by picking on trade or fabricating numbers; whatever they could to undermine the system. While not all of the anti-imperial was communist or even socialist- there were indeed a faction for an independent imperial state, their collaboration was considered a necessary part of the underground movement. Refugees would smuggle out of Vladivostok to elsewhere, even Korea, which although loyal in government to Russia, still managed to be a hotbed of resistance in at least the non-violent sense. Others went to China, Japan or the United States, forming yet more immigrant communities and therefore encouraging more rumours of a ‘Yellow Scare’. Nevertheless Russian action was taken to reduce the need for such forms of resistance by offering improvements of infrastructure and living standards, particularly in the near medieval states of Mongolia, Tannu Tuva and Xinjiang.[5] Rights were also given to improve the treatment of people in Manchuria, particularly swindling of local farmers and business men, while also removing favouritism towards Russian merchants. The biggest act though would take another 2 years to come into effect.

Admiral Alexander Kolchak, a major naval commander and eventual governer of the Far East’s navy.

The Far East Act of Spring 1918 was an early attempt to address this by offering major construction projects and work for the increasing job market that was opening up as the country as a whole modernised towards Western standards. Russian workers across Siberia jumped to the chance to earn new money, while being provided new homes of their own, drastically reducing unemployment. This was also done to recruit native peoples to get them a working part of the economy and reduce dissent of course, so it proved to be quite an effective move. One disadvantage and complaint was that it reduced the need for the military to intervene, which led some soldiers to protest about this development. While not on a major scale, this proved a mild inconvenience to the military governors in the region. Party funding went into promoting the liberals more, though there was a move towards conservativism as well in this stage. The politicisation of the local people's there allowed some degree of pacification by giving them the right to vote, something they had never possessed under Chinese rule or their attempts at precious self-rule, and this did make them more popular in many urban circles, though the countryside was harder to adapt to the new order of things. [6]

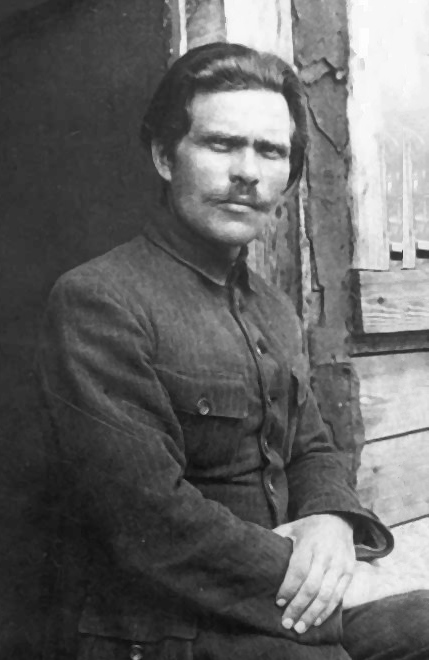

While there were moderates all around, there was a major presence of the extremists of the political spectrum, particularly the parties wishing a return to absolute monarchy or an extension of imperialism. General Pyotr Nikolayevich Wrangel was one of these individuals. Wrangel saw the humiliation Russia had underwent from its defeat in Europe and wished to seek vengeance upon the Germans for taking away what was rightfully theirs. Particularly harsh in his role of putting down the Ukrainian rebellion, he was well esteemed within the nation and so people would listen to his views, building up upon existing conservative values and fears, with some blaming the Jews for allowing Russia’s war efforts to be sabotaged, while others blamed the ineptitude of Tsar Nicholas and of Prime Minister Kerensky. In 1921, Wrangel with a coalition of other nationalistic individuals who had been commited patriots such as Anton Denekin and Grigory Semyonov, forming the Russian Union of Patriots, a party wanting to “make Russia great again” and subvert German authority in Europe. While this was its main aim, it also wanted to curb the influence of ‘anti-Russian’ influences such as Judaism, Islam, non-Orthodox Christians and Buddhists, as well as extend its control in the Far East. Wrangel and his group, particularly lieutenant Semyonov were interested in not only maintaining but growing Russian control over China, hoping to take more and more land for the Motherland, while settling sparsely populated territories with ethnic Russians to help the ‘Slavic Race’ continue to expand. Wrangel took a more reasoned approach generally however, and made it clear that his desire besides the rich Manchuria and strategically viable Mongolia was merely to establish a line of vassals which would answer to Russia’s beck and call, rather than undergo the potentially terrifying task of annexing China and Korea. Of course, they were also fiercely anti-communist and willing to depose of the revolutionary regime in Tokyo as well, also hoping to regain lost territories in southern Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands, with Semyonov even proposing to dismantle Japan into independent vassals. While extremely ambitious the party was not too open about most of these aims in public, generally preferring to be quite vague by taking back ‘everything that was lost and more’, as being open about imperialism would frighten the people and foreign nations. Nevertheless for now, their anti-communism and opposition to German dominance in Europe allowed them to see friendly partners in France, Britain, Italy and America, while in time, diplomatic relations would even start to redevelop with their age old rivals the Turks. Despite being viewed as racially ‘inferior’ by some of the RUP and the general public, the changes in administration of Turkey started leaning the common interests of the RUP and some of the political groups in the declining Ottomans and their successors. While their chances of political power were small in the relatively less turbulent period of the early 1920s, the success of the Party would grow over time as people became disillusioned.

An image of the Russian Union of Patriots Great Leader Pyotr Wrangel, a ruthless man who wished to work with imperial authority to bring about a new age of glory for Russia and her people.

Liberals and quasi-fascists were of course not the only political groups in Russia that were part of the democratic system, merely the more noticeable members. There were several other major parties that competed with them however. One of such was the old Menshevik party, which had survived the destruction of their extreme Bolshevik kin by moderising, to the point where they were now no more radical than the Labour Party of the United Kingdom, though their influence was of course monitored by Tsarist presence in the Duma. They campaigned peacefully for the enablement of the rights of workers and a reduction in wage gaps, while also disestablishing the old aristocracy and reducing the Tsar to a ceremonial role in maintaining the nation. While with sympathisers, this view was definitely a controversial one in a state where the Tsar still retained some level of political power, and thus it did not earn them the love of that many. The relatively conservative Orthodox party was definitely not as extreme as the RUP, but nevertheless called for increased reverence of the Tsar and the divine right he had, along with an increase in Church authority to levels beyond even their original forms [7]. While with some endorsement from Tsar Nicholas personally, these would not tend to be as popular outside the most religious areas or those of non-Christian belief, and so local resistance was met. While not as turbulent as earlier in the century, the Nicholatian democracy was not a period of silence either, the conflict was merely on an ideological level instead.

As the decade moved on, the prince Alexia’s health deteriorated once again due to haemophilia, something that had crippled the boy for life. This time it was more intense than ever and he was unfortunately hospitalised as a result of this, with many not knowing if the boy would live. The royal family no longer had the mad monk Rasputin in their vicinity, as he had gone east into the Mongolian desert in search of holy relics, wanting to find properties that he could use to make himself more powerful. Mongolia however was too harsh for the hardy magician and he was never heard from again from 1920 onwards, with some claiming he became a hermit in the desert. Nevertheless, without him increased medical attention went into the rescue of prince Alexei to bring about a change in his health. However, while western medical techniques were seeping the way into the nation, either legally through trade or illegally through smuggling, it was too little, too late for the prince. He was pronounced dead on the 13th of April 1922, with mourning throughout the nation. Few were hit harder than the Royal parents, who went into solitude for a while after this. A state funeral was held in the 21st of June to say farewell to the former heir to the throne, with a parade of tens of thousands gathering in St. Petersburg to deal with the loss. The tragedy was further ensnared by economic issues, as Kerensky's government was not handling the economic recovery plan as well as hoped, while also there was the issue of finding more money to fund the Far East act. The increased unpopularity of the Duma made it clear that another political election must happen soon.

The elections for the next government began in May 1923, an apt time to recover from tragedy and economic woes. At least a dozen political parties took part in this event, though several came to dominate. The Liberals lost a large number of seats due to their economic mishandling, while the Mensheviks, Conservatives, Orthodox and DUP all increased in popularity. Without the threat of Bolshevik revolution, the nation could rest easy in that regard, but republicans, illegal under the Tsarist constitution were still present in the voting populace. Most of these were fortunately democratic in their leanings, and unbeknowingly, many of the liberals and Mensheviks were secret republicans, so this was understandable. Nevertheless, the liberals managed to bounce back after Kerensky's resignation to higher levels, though not enough to secure a majority over the Duma. The Mensheviks were thus the second highest ranking party in the senate, and thus after a week of elections throughout the country, the two parties were forced to form a coalition together that would run the nation. Conflicting values and philosophy between the groups was quite noticeable and therefore there was certainly friction in how things ultimately worked out, but the nation continued to do its best in the face of such change.

As Russia as a nation would develop, the first half of the democracy phase was over. The results of the second set of elections allowed a liberal-Menshevik coalition which would ensure that the nation promoted progressive and socialistic values, while trying to improve relations with Japan and other socialist leaning nations. This would however lead to a reduction of Anglo-French aid, and while the government was competent, it started to lead the way for extremists to upset te established order, while democracy continued to try and survive.

[1] From March 1915 to January 1916, armed rebellion was a big factor within the Ukraine and as a result, Russian politics.

[2] Like OTL’s Taisho, this era was not amazing for Russia’s economy, but this was the best the average Russian citizen may have for years, for people generally received good treatment as long as they weren’t communist or anarchist. That said occasional acts of anti-Semitism or anti-Turkic sentiment brewed to the surface from time to time, leaving things fairly volatile.

[3] Many of the remaining Qing and their loyalists are kept on a several mile restraining order from the duke, but others were straight up exiled or sent to the gulags.

[4] Of course o had to include Sternberg in here giving the Far East a hard time. That said, he hasn't gone into any Mongol ambitions of grandiosity and mysticism, and instead to Orthodox missionary efforts in Manchuria, sponsoring the church quite heavily from personal finances.

[5] Even compared to places like Crimea and Central Asia, these areas were backward and needed to be managed effectively to blossom as modern nations. No such modernisation efforts were made in Qinghai though, which angered locals there, while opening later opportunities for exploitation.

[6] Naturally as with much of Eurasia, the countryside is more reactionary and religiously conservative than the cities, thus often being less open to invaders who will take their crops.

[7] Not exactly democratic, but still a good improvement over the DUP morally.