That would be awesome thanks  . It's just some research from th Russo-Japanese war suggested that th Korean government and populace preferred the Japanese to the Russians at the time due to less religious/ethnic differences and better treatment.

. It's just some research from th Russo-Japanese war suggested that th Korean government and populace preferred the Japanese to the Russians at the time due to less religious/ethnic differences and better treatment.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Red Sun Rising: The Reverse-Russo-Japanese War

- Thread starter Forbiddenparadise64

- Start date

Don't worry guys, there will be more in this at some point, I'm just very busy ATM. Hope all is well

Just finished catching up with this TL. It's really good and I want more.

And that's exactly what you'll get

The Republic’s Early Days: 1917-1921

Greg Peterson, Japan’s Rise on the Global Scene, pp.12-17

With the matter of the civil war over once and for all, the Japanese nation was now free to consolidate itself as a force to be reckoned with on the global frontier. It would no longer be held back by the ineptitude of the imperialists and would be free to the work of the people, at least in theory. However, the new nation would need to develop on the flaws that the country was having, with these being covered in several different ways, with the first of these being political in nature.

A coalition of several different socialist parties, major and minor had overthrown the imperialists, along with anarchists, pro-shogun revival elements, and other more obscure groups. However, bickering did exist between the main groups, despite the de-facto dominance of the Radical Proletarian Front, and the Democratic Union for Progress’s numbers. The Radical Proletarian Front made the decision to amalgamate itself with smaller ‘compatible’ socialist parties and individuals to form the ‘Communist Party of Japan’, with an expanded membership and reach over the country as a result. Soon, there was dissidence from those in the DUP who were not willing to accept the new order of an authoritarian state, and thus drastic action was necessary. The Spring Purge of 1917 was such a move to eliminate more liberal or ‘counterrevolutionary’ socialist movements from the country, killing, firing or exiling different members of the group. It is estimated that over 2000 people lost their lives as sympathisers were found and executed, while over 30,000 fled the country, either by force or voluntarily. Many of these democratic socialists moved into sympathetic countries such as the newly established Philippines, or the west coast of the United States, where the local Japanese communities would experience a strong anti-communist atmosphere, even stronger in fact than that of the average American. [1] A number of refugees though, ended up going southwards into the Nauru Free Territory, boosting the small population of this anarchist attempt at utopia. [2] As time went on, anarchist idealists from around the world would visit this strange little island.

With opposition effectively silenced, the People’s Shogun Sakai set about organising the nation into a relatively centralised system, eliminating the need for local lords to rule over particular areas. Instead, councils would be set up in local areas, primarily in the cities, but also in the countryside to some extent, allowing the local workers’ concerns and needs to be organised and directed efficiently and quickly. These councils would of course answer to the government, though they would be separate from the independent trade unions that allowed the workers their rights. Within the cities, the industrial centres, already well established from Japan’s capitalist stage, would be similarly put under the control of trade unions, though these would most often answer to the state in general affairs. Even General Secretary Katayama, who was more cynical on Japan’s progress before the revolution, admitted that Japan’s pre-existing industry made the urban transitions “a shrunken giant.” Feedback regarding conditions would be encouraged, but any anti-socialist thought would be met with hostility immediately. Factories and mines would have their own militias who would be put there to ‘protect the people’ from revisionists and to minimise the risk of mutinies, which was something the leadership of the country was worried might happen. Katayama’s development of the council with regard to this made the nation better able to both prevent and deal with rebellion, as tightening authority would be able to root out dissent and act quickly, while improving working and living conditions would mean there would be less incitement to revolt; he had gained the best of both worlds. This would not be perfect however; the Hiroshima Bread Riot of 1918 was an example of when this system turned out to be flawed, as the decision decided upon by the Hiroshima People’s Council was not one popular with the average worker in regard to how much bread would need to be produced, as well as the wages for those bakers. Protests occurred outside the factories with workers boycotting the industry, leading to food shortages across southern Japan lasting from February till June. The police forces moved in swiftly, arresting about 400 workers and making the ringleaders ‘disappear’. The damage had been done though, and so Katayama implemented the Baker Act, which would allow the bakers themselves to have direct say upon their wages and production quotas with the officials. This however dissatisfied many of the other industrial workers, who viewed this as favouritism. Those in industry saw it as particularly humiliating, as those who were preparing to fuel and modernise the country felt marginalised. On the other hand, there were those voices such as Yamakawa who felt the country wasn’t going far enough, and if the authorities held a tighter leash on the nation, the riots and ones like them would never have happened. This pressure led to increased disapproval of Katayama from the rest of the People's’ Council, and so increased decisions were made to reduce his power and influence in the nation.

In the countryside, the situation was significantly different. Here, the people faced a less radical turnover of their lives. They were no longer made to have fealty to local nobles and forced to pay taxes to these, and the amounts of their labours they would be allowed to keep would be increased. This showed some favourable responses from many of the farming communities, especially the poorest among them. Schemes were set up to make sure that collections of resources would not involve abuse of the common people and their needs, particularly providing benefits to those in search of jobs, hoping to encourage them to find new work. However, many among these communities were still dissatisfied, still having to pay significant taxes towards the city peoples as well as large amounts of their grain and meat. Any riots by such workers would be put down, with many being arrested as a result. The biggest problem however, was that many were sympathetic towards the old regime, and in favour of the Emperor over this new communist system. Those in the government, particularly Yamakawa, felt frustration with such a reactionary influence within such a major proportion of the working class. [3] As a result, he called a meeting of the Kyoto Council to discuss the matter of how to root out reactionary elements within the former peasantry. A happy rural workforce would eliminate the risk of revolution against the state, and unify the nation towards the goal of true communism and equality, while also allowing for more food and resources to be available for the cities, improving the nation’s well being. Drastic measures would need to be taken though, and a group made for the specific purpose of rooting out ideological enemies would need to be put in place, both for the countryside, and for the cities. Ironically, an old feudal element would return in the form of the ninja, a highly skilled class of warrior, trained in stealth, discipline and efficiency. With the reestablishment and modernisation of such a guild, they could prove a formidable secret police force which would make the nation more stable and give the Party a greater level of control by which they could guide the common people towards their goal. In September 1918, the Ninja were officially and secretly re-established under the wardenship of Sanzo Nosaka, a communist agent and organizer, working separately to the normal police force, employing informers who would listen in on the conversations of people in the markets to note if anything suspicious would occur.[4] A further degree of arrests and purges would occur in the next couple of years. One of the victims of the movement would be Sakuzo Yoshino, who had been a member of the DUP and wanted a socialist-rooted democracy rather than this ‘dictatorship of the proletarian’ that the Communist Party had established. This did of course become the source of significant criticism from many others in the government, including Sakai himself, who thought the solution should instead be done with a use of propaganda and tokens of good will that would win the people over to his side, arguing that violence should only be a last resort. Additional criticisms were made to the hypocrisy of Katayama, who himself had been a member of the DUP before defecting to the RPF, and so was often distrusted and seen of as paranoid. Despite these criticisms, it was too late for Yoshino.

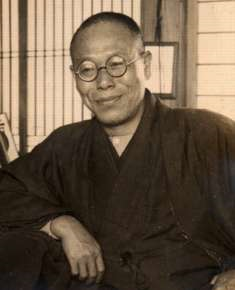

Sakuzo Yoshino, one of those purged in the winter of 1918/1919 following the reestablishment of the Ninja guild.

He and hundreds of others, including fellow democrat Tokuzo Fukada, were arrested, put on trial for ‘compromising the Revolution’ and summarily executed under Katayama’s orders, though Fukada did manage to escape on the way to his death sentence and find refuge in Nanking, where he told the people living there what was happening under the communist regime. China’s then leader Sun Yat-Sen was not as invested in the use of such propaganda, as while he was by no means friendly towards communism, he saw the formation of a republic as the primary goal, even if socialists of more moderate varieties would be involved in the system as well. Others however, particularly Chiang Kai Shek, commander of the Republic’s armed forces, wished to use this to isolate Japan by bringing out news of the atrocities under the regime. [5] News of his escape and welcoming into China led to Sino-Japanese relationships deteriorating on a national level, as the two started to become almost hostile to one another. Chiang went as far as to conduct his own set of purges in the autumn of 1919 to root out communists and sympathisers, with many rounded up and executed, while a minority made their way to Japan and secretly to Korea.

Sakai was optimistic for the progress of Japan towards being a modern socialist nation, and his moderate and populistic methods of obtaining the people’s support were successful, if criticised by other voices in the Party.

Meanwhile, the exiled communist groups from around the world started moving into Japan as a safe haven for them to express their viewpoints and contribute to a society. Sakai and Katayama had created a new type of society run by the people, and they would want to find refuge from reactionary assassins and learn how to spread the revolution to the global stage. Sakai was very egalitarian in his viewpoints, and his promotion of Esperanto as a second language, to be taught in schools across the country as a mandatory lesson, would in his view help destroy the gaps between different languages and cultures, rejecting the pseudo-scientific racism that other nations were using. Sakai’s idealism was welcomed by many of these immigrant socialists, particularly exile Leon Trotsky, who saw internationalism as an excellent pursuit for the nation, even taking on Sakai’s Esperanto. As a former Menshevik, he also favoured the more moderate stance of social policy, with a diplomatic approach to solving problems within the country, while hoping to fund revolutionary movements elsewhere as soon as possible. Sakai considered appointing Trotsky as the country’s foreign minister, though in hindsight this would put him at risk of assassination, so he instead promoted him in January 1920 with a seat within the People’s Council and put him in charge of the ideological board, which would check the ideological purity of proposed new acts, communicating with Arahata who would make this into propaganda. Rosa Luxembourg, a German communist, also supported Sakai’s democratic and semi-syndicalist manner of leadership, while denouncing Katayama’s purges as ‘a travesty’. However, several of the international immigrants did not favour the relatively moderate stance shown by Sakai, and sided with Katayama in his view of development and of the propositions for Japan’s future. Vladimir Lenin, the former leader of Russia’s fledgling Bolsheviks, was even strongly sympathetic with Yamakawa and his call for a ‘total’ model of socialism, where the entire state would push forward towards its common goal, rather than bickering under different leaders in a council. While disagreeing about the treatment and emphasis of the rural classes, they agreed that a more authoritarian state would be a necessary act of progress for the nation’s well being, considering the official position too lenient, with even Katayama’s actions not being satisfactory to organise the state of society. Always a supporter of decent international relations for the sake of the country’s development, Lenin was willing to work with the Japanese towards this common goal of world revolution regardless, even if he fell out with Trotksy as a result of factional differences.

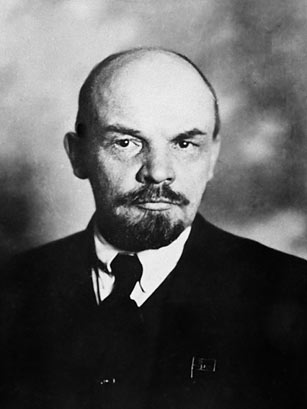

Russian refugee Vladimir Lenin became an important member of Yamakawa’s ‘Total Revolution’ faction within the party.

As the Proletarian Republic of Japan entered a new decade, the country’s efforts to mend itself from civil war had been mostly successful. Many thousands had lost their lives in this conflict, but now it was possible for veterans to move on with their lives and find a stable place within society. The military was built up to an impressive form, with the People’s Navy being one of the most powerful and respectable on the planet, even if not enough to challenge the Royal Navy or US Navy in manpower. One of the early projects suggested by Katayama was the construction of many destroyer ships that would intimidate Japan's enemies and provide devastation on the seas. However, these early destroyers tended to not be particularly efficient in their performance, with many in the government thinking this was yet another waste of resources from Katayama. Instead research went into building new types of submersible which could be used to ambush enemy ships. A change in tactics in the navy was the abolition of the 'Bushido Honor' method, or the doctrine that only explicitly military ships could be attacked, leaving trading and civilian ships ignored. For pragmatic reasons, this was dropped, as it would allow breathing space for any enemy fleets, and given the 'rational' mindset the new atheistic leadership had, it would be dropped in favour of an indiscriminate attitude towards enemy ships.

_Taisho_11.jpg)

One of the country's many ships built during the early post-establishment period, the 'Revolutionary Sword' was just one of the first of Japan's growing People's Navy, that would make their navy a force to be reckoned with.

Unemployment figures were also dropping dramatically as Japan opened up new work opportunities, making sure that people were fed and able to work in factories, farms or mines. Japan’s limited resources naturally made this somewhat difficult, but the country’s leadership remained optimistic for the restoration of the nation. With most new policies sorted out, finishing off the recovery from the war, militarily and economically was the new priority that would allow the nation to prosper. Not only would their military and economy be restored, but would be improved over their old forms, with production of steel, timber, oil and various cottons being of great value, particularly in the natural resources of Formosa. In addition, Sakai and Katayama were beginning to plan something that would change the course of Japan- the Five Year Plans. These would help build the nation’s industrial power, upgrade its military to a maximum level, and moralise its population in the name of liberating the peoples of East Asia and eventually the world, either through force or through diplomacy. Japan couldn’t fund a global revolution on its own, so it would need allies in the form of other nations in Asia and the world, perhaps even satellite states if a war with China or Russia was to go favourably. [6] With a Japan willing to fund revolutions in Asia, the western powers looked on warily.

Hope this is a good update for you.

[1] While Japan has a dramatically smaller pool of influence than Russia generally, the United States would always be wary of a significant Pacific nation turning communist, especially one not far from their military bases such as Guam and Hawaii.

[2] More on them soon.

[3] With a more authoritarian and agrarian bend to his ideology, Yamakawa gives off semi-Maoist vibes, and while he doesn't fall to corruption as easily as Stalin or Mao, his ideals for the future would indeed involve much violence.

[4] While effectively functioning as a secret police force, with maximum training in their art and secrecy, they would not be used nearly as frequently as the NKVD, and tended to be directly submitted to the Party rather than a force in their own right.

[5] Throughout the decades of their coexistence, China and Japan continued to remain in hostility to one another on governmental levels, despite Japanese attempts at reconciling the two. However, both nations would eventually become involved together in the ‘Eastern Campaign’ of the Second Great War, both supported anti-colonial forces in the Indonesian War for Independence, and both denounced the atrocities of ‘Bepul Xiva’ in the Central Asian Wars.

[6] A not so subtle taster for things to come.

The Republic’s Early Days: 1917-1921

Greg Peterson, Japan’s Rise on the Global Scene, pp.12-17

With the matter of the civil war over once and for all, the Japanese nation was now free to consolidate itself as a force to be reckoned with on the global frontier. It would no longer be held back by the ineptitude of the imperialists and would be free to the work of the people, at least in theory. However, the new nation would need to develop on the flaws that the country was having, with these being covered in several different ways, with the first of these being political in nature.

A coalition of several different socialist parties, major and minor had overthrown the imperialists, along with anarchists, pro-shogun revival elements, and other more obscure groups. However, bickering did exist between the main groups, despite the de-facto dominance of the Radical Proletarian Front, and the Democratic Union for Progress’s numbers. The Radical Proletarian Front made the decision to amalgamate itself with smaller ‘compatible’ socialist parties and individuals to form the ‘Communist Party of Japan’, with an expanded membership and reach over the country as a result. Soon, there was dissidence from those in the DUP who were not willing to accept the new order of an authoritarian state, and thus drastic action was necessary. The Spring Purge of 1917 was such a move to eliminate more liberal or ‘counterrevolutionary’ socialist movements from the country, killing, firing or exiling different members of the group. It is estimated that over 2000 people lost their lives as sympathisers were found and executed, while over 30,000 fled the country, either by force or voluntarily. Many of these democratic socialists moved into sympathetic countries such as the newly established Philippines, or the west coast of the United States, where the local Japanese communities would experience a strong anti-communist atmosphere, even stronger in fact than that of the average American. [1] A number of refugees though, ended up going southwards into the Nauru Free Territory, boosting the small population of this anarchist attempt at utopia. [2] As time went on, anarchist idealists from around the world would visit this strange little island.

With opposition effectively silenced, the People’s Shogun Sakai set about organising the nation into a relatively centralised system, eliminating the need for local lords to rule over particular areas. Instead, councils would be set up in local areas, primarily in the cities, but also in the countryside to some extent, allowing the local workers’ concerns and needs to be organised and directed efficiently and quickly. These councils would of course answer to the government, though they would be separate from the independent trade unions that allowed the workers their rights. Within the cities, the industrial centres, already well established from Japan’s capitalist stage, would be similarly put under the control of trade unions, though these would most often answer to the state in general affairs. Even General Secretary Katayama, who was more cynical on Japan’s progress before the revolution, admitted that Japan’s pre-existing industry made the urban transitions “a shrunken giant.” Feedback regarding conditions would be encouraged, but any anti-socialist thought would be met with hostility immediately. Factories and mines would have their own militias who would be put there to ‘protect the people’ from revisionists and to minimise the risk of mutinies, which was something the leadership of the country was worried might happen. Katayama’s development of the council with regard to this made the nation better able to both prevent and deal with rebellion, as tightening authority would be able to root out dissent and act quickly, while improving working and living conditions would mean there would be less incitement to revolt; he had gained the best of both worlds. This would not be perfect however; the Hiroshima Bread Riot of 1918 was an example of when this system turned out to be flawed, as the decision decided upon by the Hiroshima People’s Council was not one popular with the average worker in regard to how much bread would need to be produced, as well as the wages for those bakers. Protests occurred outside the factories with workers boycotting the industry, leading to food shortages across southern Japan lasting from February till June. The police forces moved in swiftly, arresting about 400 workers and making the ringleaders ‘disappear’. The damage had been done though, and so Katayama implemented the Baker Act, which would allow the bakers themselves to have direct say upon their wages and production quotas with the officials. This however dissatisfied many of the other industrial workers, who viewed this as favouritism. Those in industry saw it as particularly humiliating, as those who were preparing to fuel and modernise the country felt marginalised. On the other hand, there were those voices such as Yamakawa who felt the country wasn’t going far enough, and if the authorities held a tighter leash on the nation, the riots and ones like them would never have happened. This pressure led to increased disapproval of Katayama from the rest of the People's’ Council, and so increased decisions were made to reduce his power and influence in the nation.

In the countryside, the situation was significantly different. Here, the people faced a less radical turnover of their lives. They were no longer made to have fealty to local nobles and forced to pay taxes to these, and the amounts of their labours they would be allowed to keep would be increased. This showed some favourable responses from many of the farming communities, especially the poorest among them. Schemes were set up to make sure that collections of resources would not involve abuse of the common people and their needs, particularly providing benefits to those in search of jobs, hoping to encourage them to find new work. However, many among these communities were still dissatisfied, still having to pay significant taxes towards the city peoples as well as large amounts of their grain and meat. Any riots by such workers would be put down, with many being arrested as a result. The biggest problem however, was that many were sympathetic towards the old regime, and in favour of the Emperor over this new communist system. Those in the government, particularly Yamakawa, felt frustration with such a reactionary influence within such a major proportion of the working class. [3] As a result, he called a meeting of the Kyoto Council to discuss the matter of how to root out reactionary elements within the former peasantry. A happy rural workforce would eliminate the risk of revolution against the state, and unify the nation towards the goal of true communism and equality, while also allowing for more food and resources to be available for the cities, improving the nation’s well being. Drastic measures would need to be taken though, and a group made for the specific purpose of rooting out ideological enemies would need to be put in place, both for the countryside, and for the cities. Ironically, an old feudal element would return in the form of the ninja, a highly skilled class of warrior, trained in stealth, discipline and efficiency. With the reestablishment and modernisation of such a guild, they could prove a formidable secret police force which would make the nation more stable and give the Party a greater level of control by which they could guide the common people towards their goal. In September 1918, the Ninja were officially and secretly re-established under the wardenship of Sanzo Nosaka, a communist agent and organizer, working separately to the normal police force, employing informers who would listen in on the conversations of people in the markets to note if anything suspicious would occur.[4] A further degree of arrests and purges would occur in the next couple of years. One of the victims of the movement would be Sakuzo Yoshino, who had been a member of the DUP and wanted a socialist-rooted democracy rather than this ‘dictatorship of the proletarian’ that the Communist Party had established. This did of course become the source of significant criticism from many others in the government, including Sakai himself, who thought the solution should instead be done with a use of propaganda and tokens of good will that would win the people over to his side, arguing that violence should only be a last resort. Additional criticisms were made to the hypocrisy of Katayama, who himself had been a member of the DUP before defecting to the RPF, and so was often distrusted and seen of as paranoid. Despite these criticisms, it was too late for Yoshino.

Sakuzo Yoshino, one of those purged in the winter of 1918/1919 following the reestablishment of the Ninja guild.

He and hundreds of others, including fellow democrat Tokuzo Fukada, were arrested, put on trial for ‘compromising the Revolution’ and summarily executed under Katayama’s orders, though Fukada did manage to escape on the way to his death sentence and find refuge in Nanking, where he told the people living there what was happening under the communist regime. China’s then leader Sun Yat-Sen was not as invested in the use of such propaganda, as while he was by no means friendly towards communism, he saw the formation of a republic as the primary goal, even if socialists of more moderate varieties would be involved in the system as well. Others however, particularly Chiang Kai Shek, commander of the Republic’s armed forces, wished to use this to isolate Japan by bringing out news of the atrocities under the regime. [5] News of his escape and welcoming into China led to Sino-Japanese relationships deteriorating on a national level, as the two started to become almost hostile to one another. Chiang went as far as to conduct his own set of purges in the autumn of 1919 to root out communists and sympathisers, with many rounded up and executed, while a minority made their way to Japan and secretly to Korea.

Sakai was optimistic for the progress of Japan towards being a modern socialist nation, and his moderate and populistic methods of obtaining the people’s support were successful, if criticised by other voices in the Party.

Meanwhile, the exiled communist groups from around the world started moving into Japan as a safe haven for them to express their viewpoints and contribute to a society. Sakai and Katayama had created a new type of society run by the people, and they would want to find refuge from reactionary assassins and learn how to spread the revolution to the global stage. Sakai was very egalitarian in his viewpoints, and his promotion of Esperanto as a second language, to be taught in schools across the country as a mandatory lesson, would in his view help destroy the gaps between different languages and cultures, rejecting the pseudo-scientific racism that other nations were using. Sakai’s idealism was welcomed by many of these immigrant socialists, particularly exile Leon Trotsky, who saw internationalism as an excellent pursuit for the nation, even taking on Sakai’s Esperanto. As a former Menshevik, he also favoured the more moderate stance of social policy, with a diplomatic approach to solving problems within the country, while hoping to fund revolutionary movements elsewhere as soon as possible. Sakai considered appointing Trotsky as the country’s foreign minister, though in hindsight this would put him at risk of assassination, so he instead promoted him in January 1920 with a seat within the People’s Council and put him in charge of the ideological board, which would check the ideological purity of proposed new acts, communicating with Arahata who would make this into propaganda. Rosa Luxembourg, a German communist, also supported Sakai’s democratic and semi-syndicalist manner of leadership, while denouncing Katayama’s purges as ‘a travesty’. However, several of the international immigrants did not favour the relatively moderate stance shown by Sakai, and sided with Katayama in his view of development and of the propositions for Japan’s future. Vladimir Lenin, the former leader of Russia’s fledgling Bolsheviks, was even strongly sympathetic with Yamakawa and his call for a ‘total’ model of socialism, where the entire state would push forward towards its common goal, rather than bickering under different leaders in a council. While disagreeing about the treatment and emphasis of the rural classes, they agreed that a more authoritarian state would be a necessary act of progress for the nation’s well being, considering the official position too lenient, with even Katayama’s actions not being satisfactory to organise the state of society. Always a supporter of decent international relations for the sake of the country’s development, Lenin was willing to work with the Japanese towards this common goal of world revolution regardless, even if he fell out with Trotksy as a result of factional differences.

Russian refugee Vladimir Lenin became an important member of Yamakawa’s ‘Total Revolution’ faction within the party.

As the Proletarian Republic of Japan entered a new decade, the country’s efforts to mend itself from civil war had been mostly successful. Many thousands had lost their lives in this conflict, but now it was possible for veterans to move on with their lives and find a stable place within society. The military was built up to an impressive form, with the People’s Navy being one of the most powerful and respectable on the planet, even if not enough to challenge the Royal Navy or US Navy in manpower. One of the early projects suggested by Katayama was the construction of many destroyer ships that would intimidate Japan's enemies and provide devastation on the seas. However, these early destroyers tended to not be particularly efficient in their performance, with many in the government thinking this was yet another waste of resources from Katayama. Instead research went into building new types of submersible which could be used to ambush enemy ships. A change in tactics in the navy was the abolition of the 'Bushido Honor' method, or the doctrine that only explicitly military ships could be attacked, leaving trading and civilian ships ignored. For pragmatic reasons, this was dropped, as it would allow breathing space for any enemy fleets, and given the 'rational' mindset the new atheistic leadership had, it would be dropped in favour of an indiscriminate attitude towards enemy ships.

_Taisho_11.jpg)

One of the country's many ships built during the early post-establishment period, the 'Revolutionary Sword' was just one of the first of Japan's growing People's Navy, that would make their navy a force to be reckoned with.

Unemployment figures were also dropping dramatically as Japan opened up new work opportunities, making sure that people were fed and able to work in factories, farms or mines. Japan’s limited resources naturally made this somewhat difficult, but the country’s leadership remained optimistic for the restoration of the nation. With most new policies sorted out, finishing off the recovery from the war, militarily and economically was the new priority that would allow the nation to prosper. Not only would their military and economy be restored, but would be improved over their old forms, with production of steel, timber, oil and various cottons being of great value, particularly in the natural resources of Formosa. In addition, Sakai and Katayama were beginning to plan something that would change the course of Japan- the Five Year Plans. These would help build the nation’s industrial power, upgrade its military to a maximum level, and moralise its population in the name of liberating the peoples of East Asia and eventually the world, either through force or through diplomacy. Japan couldn’t fund a global revolution on its own, so it would need allies in the form of other nations in Asia and the world, perhaps even satellite states if a war with China or Russia was to go favourably. [6] With a Japan willing to fund revolutions in Asia, the western powers looked on warily.

Hope this is a good update for you.

[1] While Japan has a dramatically smaller pool of influence than Russia generally, the United States would always be wary of a significant Pacific nation turning communist, especially one not far from their military bases such as Guam and Hawaii.

[2] More on them soon.

[3] With a more authoritarian and agrarian bend to his ideology, Yamakawa gives off semi-Maoist vibes, and while he doesn't fall to corruption as easily as Stalin or Mao, his ideals for the future would indeed involve much violence.

[4] While effectively functioning as a secret police force, with maximum training in their art and secrecy, they would not be used nearly as frequently as the NKVD, and tended to be directly submitted to the Party rather than a force in their own right.

[5] Throughout the decades of their coexistence, China and Japan continued to remain in hostility to one another on governmental levels, despite Japanese attempts at reconciling the two. However, both nations would eventually become involved together in the ‘Eastern Campaign’ of the Second Great War, both supported anti-colonial forces in the Indonesian War for Independence, and both denounced the atrocities of ‘Bepul Xiva’ in the Central Asian Wars.

[6] A not so subtle taster for things to come.

Last edited:

trurle

Banned

With a Russian economy ruined by defeat in Europe and a approximately year-long Japanese occupation of trans-Amur area, i think the Khabarovsk Bridge project is postponed indefinitely. It will mean lagging development and rampaging separatism on the Far East of Russia.

Also, without clear victor in your equivalent of WWI, the League of Nations (formed 1920 IOTL) is not going to appear, because it would not include the Germany - currently the most powerful state in continental Europe. It mean also no Washington Naval Treaty (1922 IOTL).

I expect most national leaders in Forbiddenparadise64 world in 1916 to feel insecure, threatened or even scared to death - therefore pushing the arms race to the limits.

Outline of arms race:

1) Continuation of capital ship buildup by Britain, Germany and United States and may be Italy (expect like 100+ dreadnought battleships on each side by beginning of 1919)

2) Impoverished nations like Japan, Russia, Spain, Ottoman empire etc. will be clearly unable to compete, therefore investment would be made into asymmetric warfare. It mean espionage, sabotage, unusual coastal artillery, rockets, torpedoes, naval mines and aircraft.

In particular:

a) Russians are going to push the idea of heavy/torpedo bomber https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sikorsky_Ilya_Muromets to the extreme and with much rigour. Japanese are likely to acquire the idea, downed sample or even blueprints (through communist underground channels) very soon. I expect Ilya Muromets - derived torpedo bombers capable to carry 450mm (1-ton) torpedoes to be produced in Russia and Japan by 1924, followed shortly after by British. IOTL torpedo bomber development was much delayed interwar due lack of funds despite clear perspectives, with first effective torpedo bombers (Fairey Swordfish) flying in 1934.

b) Base bleed coastal artillery. It was nearly ASB such a simple and effective solution to extend an artillery range was overlooked until 1969. Would be a closely-held state secret of one or few cornered nations though. Very easy to conceal in plain sight unlike the heavy bomber.

c) Early "Multiple Launch Rocket System" in coastal installations (similar to WWII British Z battery) to provide some deterrent against long-range naval bombardment (have a shorter production cycle time compared to ultra-heavy artillery and may be considered as a viable stopgap coastal defence weapon).

d) Earlier development of magnetic and acoustic mines/ torpedoes (1931 IOTL) The premature versions would be very imprecise though, due reliability and noise issues in their highly-complicated detonators and mechanical guidance systems.

e) Heavy investment in the sabotage tactics. Imagine suicidal agents of Japanese Revolutionary Army with sacks of explosive in their stomachs infiltrating the British or US ports. It is not really going to work on large scale, but few top-notch targets can be destroyed, and tightened security will reduce productivity more than saboteurs can achieve.

f) Early fast torpedo boats (the Kitty Hawk hydroplane was developed in 1911 IOTL, but idea was shelved for decades)

g) More emphasis on submarine warfare (British, Germany and Japan are likely pioneers)

h) Tanks development approximately in line with OTL (ideas for armoured vehicles were too straightforward and widespread by 1914 IOTL)

P.S. I disagree with Forbiddenparadise64 placing Kotoku`s anarchists initally to Hokkaido. With land policy of the Meiji government (encouraging ex-soldiers to settle on free land lots in Hokkaido) the Hokkaido is going to be one of the most loyal regions of the crumpling Japanese Empire. Ainu did not have neither political power nor dense population in 1915, therefore their efforts on revolution would be negligible. Instead, i would place anarchists`s hotbed to Kobe-Osaka-Shiga-Kyoto quadrangle (roughly Kansai region) which had a social stress far exceeding average due local impoverishment and also have a well-established organized crime network (the Yamaguchi-gumi, the largest Japanese Yakuza syndicate, can be traced back to 1915 in Kobe IOTL)

P.P.S. The new post by Forbiddenparadise64 is generally ok, but some points are messed up:

a) Is is strange to find "oppression by local lords" in Japan about 1915. The local self-government system (councils etc.) was established in 1888-1890 (see book

Japan's Modern Myths: Ideology in the Late Meiji Period

by Carol Gluck , p. 192 for the reference). I.m.h.o., if rural social tension should exist in rural Japan, it would be dominated by recent social stratification among peasants, due ongoing mechanization and advances in fertilizers for agriculture. Simply, the more conservative peasants will find their vegetables too expensive to be competitive, and anyway the food prices would be falling rapidly forcing mass migration to the cities.

b) The national fleet around 1920 cannot be built around destroyers. Destroyers according to doctrine of the epoch had a very limited role - to protect the capital ships (battleships) from torpedo boats attack. Only after advances in submarine warfare the destroyers has become useful as commercial fleet protectors - but only against weaker opponents who can not afford cruisers. Otherwise, the cruisers were considered more effective shipping lane protectors against advanced enemy. So Japan may opt for cruiser fleet (implemented IOTL, but clearly untenable in this ATL given abundance of enemy battleships in sea due ongoing British- German confrontation), or submarines + torpedo boats + aircraft as a low-cost asymmetric alternative.

By the way, of 15 Minekaze-class destroyers you pictured as exemplar, 9 were sunk by submarines and 2 by airstrikes. In return, all 15 Minekaze-class destroyers have managed to sunk 1/2 of minesweeper and 1/3 of submarine (all in joint action with newer destroyers). Of course, Minekaze-class was obsolete by WWII, but even for obsolete ship the performance was abysmal.

Also, without clear victor in your equivalent of WWI, the League of Nations (formed 1920 IOTL) is not going to appear, because it would not include the Germany - currently the most powerful state in continental Europe. It mean also no Washington Naval Treaty (1922 IOTL).

I expect most national leaders in Forbiddenparadise64 world in 1916 to feel insecure, threatened or even scared to death - therefore pushing the arms race to the limits.

Outline of arms race:

1) Continuation of capital ship buildup by Britain, Germany and United States and may be Italy (expect like 100+ dreadnought battleships on each side by beginning of 1919)

2) Impoverished nations like Japan, Russia, Spain, Ottoman empire etc. will be clearly unable to compete, therefore investment would be made into asymmetric warfare. It mean espionage, sabotage, unusual coastal artillery, rockets, torpedoes, naval mines and aircraft.

In particular:

a) Russians are going to push the idea of heavy/torpedo bomber https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sikorsky_Ilya_Muromets to the extreme and with much rigour. Japanese are likely to acquire the idea, downed sample or even blueprints (through communist underground channels) very soon. I expect Ilya Muromets - derived torpedo bombers capable to carry 450mm (1-ton) torpedoes to be produced in Russia and Japan by 1924, followed shortly after by British. IOTL torpedo bomber development was much delayed interwar due lack of funds despite clear perspectives, with first effective torpedo bombers (Fairey Swordfish) flying in 1934.

b) Base bleed coastal artillery. It was nearly ASB such a simple and effective solution to extend an artillery range was overlooked until 1969. Would be a closely-held state secret of one or few cornered nations though. Very easy to conceal in plain sight unlike the heavy bomber.

c) Early "Multiple Launch Rocket System" in coastal installations (similar to WWII British Z battery) to provide some deterrent against long-range naval bombardment (have a shorter production cycle time compared to ultra-heavy artillery and may be considered as a viable stopgap coastal defence weapon).

d) Earlier development of magnetic and acoustic mines/ torpedoes (1931 IOTL) The premature versions would be very imprecise though, due reliability and noise issues in their highly-complicated detonators and mechanical guidance systems.

e) Heavy investment in the sabotage tactics. Imagine suicidal agents of Japanese Revolutionary Army with sacks of explosive in their stomachs infiltrating the British or US ports. It is not really going to work on large scale, but few top-notch targets can be destroyed, and tightened security will reduce productivity more than saboteurs can achieve.

f) Early fast torpedo boats (the Kitty Hawk hydroplane was developed in 1911 IOTL, but idea was shelved for decades)

g) More emphasis on submarine warfare (British, Germany and Japan are likely pioneers)

h) Tanks development approximately in line with OTL (ideas for armoured vehicles were too straightforward and widespread by 1914 IOTL)

P.S. I disagree with Forbiddenparadise64 placing Kotoku`s anarchists initally to Hokkaido. With land policy of the Meiji government (encouraging ex-soldiers to settle on free land lots in Hokkaido) the Hokkaido is going to be one of the most loyal regions of the crumpling Japanese Empire. Ainu did not have neither political power nor dense population in 1915, therefore their efforts on revolution would be negligible. Instead, i would place anarchists`s hotbed to Kobe-Osaka-Shiga-Kyoto quadrangle (roughly Kansai region) which had a social stress far exceeding average due local impoverishment and also have a well-established organized crime network (the Yamaguchi-gumi, the largest Japanese Yakuza syndicate, can be traced back to 1915 in Kobe IOTL)

P.P.S. The new post by Forbiddenparadise64 is generally ok, but some points are messed up:

a) Is is strange to find "oppression by local lords" in Japan about 1915. The local self-government system (councils etc.) was established in 1888-1890 (see book

Japan's Modern Myths: Ideology in the Late Meiji Period

by Carol Gluck , p. 192 for the reference). I.m.h.o., if rural social tension should exist in rural Japan, it would be dominated by recent social stratification among peasants, due ongoing mechanization and advances in fertilizers for agriculture. Simply, the more conservative peasants will find their vegetables too expensive to be competitive, and anyway the food prices would be falling rapidly forcing mass migration to the cities.

b) The national fleet around 1920 cannot be built around destroyers. Destroyers according to doctrine of the epoch had a very limited role - to protect the capital ships (battleships) from torpedo boats attack. Only after advances in submarine warfare the destroyers has become useful as commercial fleet protectors - but only against weaker opponents who can not afford cruisers. Otherwise, the cruisers were considered more effective shipping lane protectors against advanced enemy. So Japan may opt for cruiser fleet (implemented IOTL, but clearly untenable in this ATL given abundance of enemy battleships in sea due ongoing British- German confrontation), or submarines + torpedo boats + aircraft as a low-cost asymmetric alternative.

By the way, of 15 Minekaze-class destroyers you pictured as exemplar, 9 were sunk by submarines and 2 by airstrikes. In return, all 15 Minekaze-class destroyers have managed to sunk 1/2 of minesweeper and 1/3 of submarine (all in joint action with newer destroyers). Of course, Minekaze-class was obsolete by WWII, but even for obsolete ship the performance was abysmal.

Last edited:

a) Is is strange to find "oppression by local lords" in Japan about 1915. The local self-government system (councils etc.) was established in 1888-1890 (see book

Japan's Modern Myths: Ideology in the Late Meiji Period

by Carol Gluck , p. 192 for the reference). I.m.h.o., if rural social tension should exist in rural Japan, it would be dominated by recent social stratification among peasants, due ongoing mechanization and advances in fertilizers for agriculture. Simply, the more conservative peasants will find their vegetables too expensive to be competitive, and anyway the food prices would be falling rapidly forcing mass migration to the cities.

Sounds like Japan might end up with its own brand of Kulaks.

Regarding aircraft, I think this ATL 1920s with the Great War outcome in Western Europe largely a push would tend to favor a brief but significant era of airships.

In general, the "age of the airship" never seems to dawn, in part because the same technological advances that make a dirigible practical also tend to enable airplanes to become more competitive.

However in this period there is a definite advantage that a medium to large size airship enjoys, and that is the matter of range and endurance. Although even the rather primitive airplanes of the era are already three or more times faster than the sky whales, they are of rather haphazard reliability and cannot stay airborne long nor achieve long ranges except as extreme stunts. The first transAtlantic crossing--the easy way, flying with prevailing winds from west to east from Newfoundland to Ireland--was achieved by Alcock and Brown in a Vickers Vimy bomber plane in 1919, but just weeks later, the British R-34 made the second crossing, the hard way against the winds over a much greater distance--starting from RAF East Fortune in Scotland somewhat east of A&B's crash-landing in western Ireland, and flying much farther west than Newfoundland. A&B covered 3040 kilometers in just under 16 hours, but reading about their flight it is evident that their survival was a bit of a miracle, whereas the R-34 made it all the way to Minneola on Long Island, New York. It took them over 4 days, but they covered 4800 kilometers--admittedly they were very nearly out of fuel when they arrived! (But obviously they'd have been fine if they had gone to Nova Scotia, or even Massachusetts, instead. And they did make it to a safe mooring, though just barely). Unlike the near-frozen and miserable pair of A&B, crash-landing in a field in Ireland, they made their goal--I forget just how large the complement aboard was but the article above names at least 5 people aboard, including one stowaway with a dog, and I believe the total was 9 or so. Furthermore upon refueling, the R-34 was well able to return to RNAS Pulham in just 75 hours with ample fuel, going faster and more easily with the prevailing winds.

Now in this ATL, both Britain and Germany are considerably better off than OTL, due to the war ending earlier. The USA never formally took sides. The Zeppelin firm is not trying to operate in a Germany with a collapsed economy nor are they under the ax of a Versailles Treaty regime with the agenda of banning all German aviation.* Neither Britain nor Germany need suffer the extreme stringency of the OTL post-war era though surely both economies will suffer something of a hangover. The rival design firm Schuette-Lanz might also be able to continue in business; with two competing German firms, the chances that airship technology secrets would be dispersed seems more likely. Germany has lost East Africa and all holdings in the Pacific but retains holdings in west Africa, and has gained a vast hegemony in the east of Europe. IIRC German satellites border on the Black Sea and the odds are fairly good that the Kaiserreich enjoys good relations with Turkey. Thus there are potential markets for a German airline even if they find both the French and British firmly opposed to letting them service their colonial holdings or fly over them. The Suez Canal airspace at least ought to remain open; if not passage over the Black sea, over Anatolia and possibly still Ottoman held Mesopotamia might be an option to reach the Indian Ocean--too bad they don't still have East Africa! Nor are there any destinations on the Indian Ocean or beyond that might welcome them--Japan or China being possible destinations but too damn far away going over the sea, whereas Russian airspace is surely closed.

At any rate, I'd think the Germans would want, for reasons of prestige as well as possible revenue opportunities, to establish a regular transAtlantic service. A direct air route to the United States (assuming they are unwelcome in Canada of course) would require diverting around Britain, either south through the Channel in sight of both a hostile Britain and France, or north of Scotland. In summer the northerly route would serve well enough; airships are unlikely to want to operate in stormy seasons (although OTL, in 1960 the USN's Operation Whole Gale demonstrated that blimps could operate and carry out missions in the worst storm season, remaining airborne in weather that grounded airplanes and demonstrating superior endurance and range while detecting all submarines attempting to slip past the gauntlet--it is of course open to question whether 1920s rigids could accomplish the same thing!) They probably could get access to the Azores but unlike airplanes, this would merely be a convenience, not a necessity.

A Zeppelin design postwar, with adequate funding, would be far superior to R-34 (which was not designed as a passenger carrier) and could surely be ready to fly as early or earlier. Despite a longer flight path it ought to be able to take on paying passengers in at least similar numbers to Hindenburg, albeit probably in notably less comfort. But still their comfort would be vastly superior to any possible airplane that could make the crossing by any route. Considering the many stops for refueling a realistic ocean-crossing airplane of the 1920s (if this could be done at all on any scale beyond Alcock and Brown or Lindbergh's near fatal stunts) the speed advantage of the airplane would be largely nullified by long delays waiting for daylight and safe flying weather. The airship just plows on, slowly but majestically, for the most part. I therefore think that in this ATL regular service from Bremen to New York, taking some 4-5 days each way, would be established by say 1922.

In these circumstances, with Britain's finances somewhat less badly off, one would expect both the RN and the RAF to be supported in developing British airships. Great things might be expected from the firms of Vickers, and Shorts, based on OTL efforts. Unlike Germany, Britain has a vast web of imperial holdings to link together. It is technically possible already in the 1920s to do this with airplanes, but they are not on the average faster or safer than possible airships of the decade. With more consistent and heavier support than OTL, I'd think an Empire scheme reaching on its major trunk route from Britain, over France and the Mediterranean to Egypt and thence either over Arabia or around it to India, and on via Singapore to Australia and ultimately New Zealand would be fully implemented before 1930, with other branches competing with the Germans for the American/transAtlantic market, a spur down to South Africa and connecting most of British Africa in between, and possibly a satellite network in the Caribbean

In turn, American investors might get in on the game. The USA is poor terrain for a transcontinental airship line, what with the Rocky Mountain range being in the way--but Zeppelins, lifted with hydrogen, were able to clear high mountains, including the Rockies on the Graf Zeppelin's world circumnavigation--more routinely, the Alps. American railroads however can come close to matching airship top speeds; the airships would only enjoy a partial advantage in being able fly more directly--but between contrary winds and the need to seek out relatively low spots in the central mountain range, not all that much so. But a large set of over-water markets does exist--West coast to Hawaii, for instance, or on from there to the Philippines. Anglo-American cooperation can create a closed loop network, and other services might run down to South America on either side of the Andes and just possibly (with difficulty and risk) over them. The South American market, particularly on the Atlantic side, is liable to European competition of course.

Would this be enough to bring in the French and Russians too? Russia could use some airships for domestic purposes--even if the Trans-Siberian RR is finished, it is still far from reaching all points of interest in the east.

And in the perspective of the 1920s right after a Great War cut somewhat short relative to OTL, the airships might look like game changers on the high seas for navies too.

The big role serious advocates such as the USN's Charles Rosendahl suggested was that of naval scout, a function traditionally done by cruisers. Airplanes operating off aircraft carriers could greatly expand the vision of fleets of course, as could seaplanes--but in the 1920s these remained limited and risky. Note that much development of carriers in the interwar years was favored by the fleet limitation treaties aimed at traditional Great War era warship types; converting cruisers or cargo ships over to carriers sidestepped some of the treaty limits. We anticipate no such treaties in this TL so the admiralties will presumably remain more focused on battleships and cruisers--surely some carriers will also be developed, but the airship alternative will also remain attractive. It is an obvious opportunity for the Germans to leapfrog the RN, and the RN must surely respond by seeking to have British airships developed for its own purposes. An airship cruising a kilometer or two up in the air can survey a vast sweep of ocean, and moves two or three times faster than any surface ship. Airplanes operating off of carriers, or seaplane tenders, are tied to their ships, whereas it is possible for airplanes (light ones, in modest numbers, to be sure) to operate off of airships by hook-on methods. In the 1920s state of the art airplanes could easily match speeds with a cruising airship. Any arguments that a carrier-based airplane could fly faster and higher could be answered with hook-on aircraft, and its base moves a lot faster, so that an airship operating a few scout planes could sweep out vast swathes of ocean, searching for enemy fleet elements or squadrons. To locate enemy subs instead might require different practices, but the British demonstrated the utility of small coastal blimps for such purposes during the Great War OTL; to secure a fleet on the high seas might require a fair number of big airships, say two really big ones as light carrier/scouts with the option of launching strike missions, and two or three moderate sized small rigids or large blimps to more meticulously and slowly probe the seas on the fleet or task force's projected course for submarines.

(As the state of the art advances in the 1930s and minimum airspeeds of high-performance warplanes rises above sustainable LTA cruise or even dash speeds, something more elaborate must be done--but I think it would be feasible for a fast airplane to intercept a trapeze slung many tens or hundreds of meters below, and use it as a pendulum to absorb excess forward speed, and be winched up quickly to the mother airship--take-off from the sky carrier would be easy of course, just rev up the engine, and drop the plane--it quickly and effortlessly gains necessary airspeed by diving. These operations would be rather daredevil for the planes, especially snagging a swinging hook at many tens of knots relative speed, but pretty safe for the airship, and even the planes are at less risk than one attempting to land on a carrier deck on the sea).

I envision yet more less glorious but useful roles for airships of various sizes on a high seas fleet--to serve as cargo delivery vehicles for instance, running vital items or couriering messengers or high ranking officers to fleet flagships far out at sea, ferrying wounded men back to shore hospitals. An airship can match speeds with any surface element (or surfaced submarine) and transfer goods either way. There are some tricks to master but I can think of how to do it.

The development of the helicopter has eclipsed many possible functions for airships, but if there were a major investment in them in the 1920s I'd think we'd see more examples of these in operation before the choppers could take over. Helicopter rotor technology could probably be well fostered by using them interim as improved, steerable props for advanced airship designs, and airships incorporating these would be of moderately more use than those without.

Other advances that can stretch the competitiveness of airships, albeit being driven into farther niche roles, would be the development of aeronautical diesel engines, improved and lightened/strengthened materials (such as synthetic gas cell materials, developed OTL in the 1930s, to replace "goldbeater's skin" gas cells which is essentially cow guts (the membranes used for sausage skins) glued onto cotton--the synthetic cellulose cells developed for the Akron and Macon were lighter, stronger, less leak, wear and rot prone, and cheaper too, for instance) for rigid members, lines, and skin material. I've mentioned some pet ideas of mine such as dynamic pendulum fast airplane hook-on, diesel engines (which were tentatively developed partially OTL, and by the way can be adjusted easily to burn mostly hydrogen), self-steering, larger area helicopter type rotors--and I have yet more in mind such as variable buoyancy without throwing away either lift gas or ballast, by using steam or ammonia as lift gases that can be converted back into condensed form.

By the early 1930s, airplanes will at last be demonstrating an approach to more or less reliable transoceanic ranges, and with their superior speed which not only gratifies travelers but allows a given number of seat/berths to serve more customers in a given time, the airships will definitely be eclipsed as major passenger carriers. But by then the investment in them might be so tremendous, that they are favored for auxiliary roles as they would not be if none had ever been built in the first place. Hook-on capabilities may extend the useful commercial lives considerably or even indefinitely--in lieu of developing massive, land hungry heavy concrete runways, heavy fast airplanes might operate off of very big airships as hook-ons, that proceed down chains of airships spotted along routes within airplane range of each other, to refuel the fast express airplanes quickly, while slow short-take-off and landing planes rise from numerous small simple airfields to join the airships in progress. Heavy cargoes can fly slowly and economically; passengers exhausted by loud and cramped fast airplanes can take berths aboard relatively quiet, steady and spacious airships to rest and dodge jet lag. The existence of the hook-on mother ship option might accelerate the commercial introduction of very fast prop planes (designed without compromise for high airspeeds, landing on the ground only occasionally at maintenance sites situated on desert salt lakes for huge natural airfields unfortunately located nowhere convenient. Eventually early jet aircraft, with short legs, can still lend their phenomenal speed to passengers in a hurry, even though the runway network does not yet exist.

Between the development of jets, turboprops, and helicopters especially with turbine engines, the airships will definitely have to retreat into the background, but I don't think they will be eclipsed completely ever. A big war might either sweep most if not quite all of them from the sky, or actually diversify their uses even more, at least for the duration.

OTL, between WWI and sometime after WWII, only the United States could boast any known economical source of the gas helium, and even for limited purposes the supply was scanty, unreliable, and not very pure. During WWII it was quite adequate to operate a large fleet of hundreds of "small" blimps on coastal patrol (or eventualy more ambitious missions such as minesweeping, another unglamorous but vital service). In this ATL, only the Americans would have the option of experimenting with helium. This will remain true until and unless the handful of other sites known OTL by now--I know of somewhere (don't know just where) in Siberia, somewhere in Algeria, and perhaps one or two other locations I forget--are stumbled upon. All are natural gas wells with a small percentage of helium trapped.

Assuming these are found no faster than OTL, the USA does not have any spare to sell to anyone, no matter how friendly. Germans, Britons, French, Russians, and lest the point be lost--possibly Japanese--must use either hydrogen or gases inferior to helium in most ways (though with some interesting compensating options) such as steam, methane, "town gas," ammonia, or even hot air. The latter, and town gas, strike me as terribly impractical; methane is as flammable as hydrogen and much worse at lifting. Steam and ammonia can be converted back and forth between liquid and gas states to achieve variable lift without venting or dropping anything. But as main lift gases they are mediocre and risky. The game is pretty much going to be all hydrogen, at least as the main lifting material.

This means they are of course vulnerable to accidents. I am not one of those people who wishes to scoff at the risks, but I will suggest that people will accept some degree of risk while traveling. And in peaceful, civil applications the risks can be managed. For military applications, much service will be in an auxiliary, back of the lines role, and even near the fronts the actual weapons will be carried by airplanes the last couple hundred miles. Airship strike carrier/scout cruisers will, like aircraft carriers of the surface which are also terribly vulnerable to enemy action, rely mainly on distance and evasion, and only as a last resort the defensive capability of their warplanes for their defense. Submarine hunter "destroyers" will not be invulnerable to the subs they seek to ferret out--OTL at least one U-boat was able to down an American blimp with its surface guns, and that blimp used helium for lift too--but they will enjoy the high ground, and have a good option of standing off far enough to be able to dodge and run. Anyway their role, as with other warships, is to go in harm's way as part of an operational fleet they serve; even if shot down, the crew might survive and anyway had a duty to alert their fellow seamen of a threat and take measures to neutralize it. A WWII era sub once spotted by an airship, even one the sub could then take out, is probably dead meat as the fleet elements converge on it.

The postwar era may push all airships back into strictly noncombatant, auxiliary roles by the 1960s, but even then OTL uses were imagined for them and in a TL where they have been extensively developed and flown, I think they'd think of yet others.

------------------------------

Now, does any of this have anything to do with Red Japan?

I say, yes obviously. OTL the Japanese were moderately interested in airship tech and were given some reparation German airships, as well as having some airship sheds disassembled and shipped there (the reparation rigids were also shipped in cut-up form and never reassembled).

Here however, they face the vast Pacific with no friends. Unlike the IJN whose initial buildup was covered by alliance with Britain, the Japanese People's Navy or whatever it is called has no cover except what they can manage themselves.

I'd think, under the circumstances, they must manage to use every trick they can think of. Rosendahl's OTL notion of airship scouting must occur to them as well. In tentatively and partially backing helium-heads like Rosendahl the USN brass was thinking mainly of a war in the Pacific, mainly against Japan. The Japanese aren't distracted by a second ocean (unless they get ambitious enough to think of going beyond Indonesia)--they have mainly the Pacific to worry about. That and of course attecks from the mainland--but the coastal powers there are technologically and industrially weak; even in the case of the Russian threat, their main industrial centers are on the far end of Eurasia and what they can build up on the Pacific, with its poor ports they hold, is only a fraction. With work and access to resources Japan can hold off anything the Russians, Chinese or Koreans can threaten them with in this era--provided they don't get help from Britain, France, Germany, or the USA.

I'd think Japanese designers would do some very ingenious if risky things with their airships; they might make them lighter if flimsier than anyone else dares do, and economize on expensive industrial materials in favor of ones their islands actually have, such as bamboo, silk and fine papers. Where they need a high-tech part, or it is clearly cost-effective, they will sacrifice to get it and use it, but they can stretch their limited resources and multiply the numbers of effective aircraft they can deploy beyond what a given budget would accomplish in one of the richer developed nations. Of course this means their crews are either very clever and meticulous, or dead quickly and often. In war, they'd have to hope to strike quickly and evade, or face certain death--but of course that is a cultural feature of Japan that the Communists are probably not going to undermine, that they are fatalistically willing to risk or even accept as certain in the course of serving the higher cause.

I've often thought that airships, which serve well to hunt submarines, can also serve well cooperating with them. A quiet airship, properly camouflaged, might spot a target for a submarine, convey a signal to it without being detected (say by shaded blink code or semaphore) to guide the sub to a lurking spot to strike an unsuspecting target. Once the enemy vessel or convoy is stricken, the airship might convey replacement ammunition to it. Vice versa submarines can operate as supply dumps for aggressively patrolling airships, that might launch aircraft or even radio-guided line of sight missiles against targets, and while the airships can't lift huge stocks of ammo, the subs can--the airship repairs to one when depleted and reloads.

OTL of course Japanese submarines were famous for their effectiveness--though unlike German, British, or American ones, they tended to stick to targeting only warships and not effectively engaging in commerce raiding--not so much for humanitarian reasons the European-derived peoples all claimed to value but immediately tossed aside once the war was on, but for reasons of bushido honor--which in a left-handed way can be viewed as a sort of harsh humanitarianism. Anyway wise or foolish, they stuck to it, reserving their often effective fire for actual enemy war ships. Suppose the Red regime "cures" them of that and Red Navy subs and dirigibles working together go all out to sink as much enemy tonnage as they can, regardless of whether it is a warship or just a tramp steamer? Might not the defense of the Home Islands of revolution be more grimly effective then, if even the USN cannot stem completely really high levels of attrition as they attempt to reach all across the Pacific? Might strike forces including such auxiliary elements have a punch out of proportion to the tonnage of the surface units, taking even a unified US/RN/French/Russian fleet by surprise?

Japan's terrible liability is its shortness of resources; once cut off from global commerce, there is only so much hardware the islanders can manufacture and expend.

I trust its revolutionary leaders, even the more fanatical among them, will be more prudent and deliberate than the militarists of OTL. They probably can and will use Banzai spirit (and ninjas!) to effect, but will not rely solely on it but rather have a plan to gain something from their sacrifices that lets them fight on. I suppose they have cards to play in inciting native uprisings against European and American colonialists, perhaps enlisting Koreans and/or Manchurians on a voluntary rather than coerced basis? Will they be smarter politicians in general? They'd better be or they are ultimately doomed.

I imagine you have some clever plans in store for them, and I hope my entirely serious plea on behalf of an airship age is useful and inspirational.

*OTL the Zeppelin firm was able to parley a deal with the United States Navy to deliver a modern Zeppelin design, ultimately the USS Los Angeles, into a stay of execution for its main plant at Friedreichshafen, though all the other airship hangars built during the war were demolished, and by the time the Los Angeles was delivered--in yet another transAtlantic flight, not to be sure without mishap, long before Lindbergh's crossing--the international situation had relaxed into the Locarno era and the Zeppelin works were left alone, to build the Graf Zeppelin, the Hindenburg, and finally Graf Zeppelin "II." But it was definitely a near-run thing for the works and a number of Zeppelin designers and workers were hired by Goodyear to come over to America to form Goodyear-Zeppelin company which built the USN's final two rigid airships, and wearing other divisional hats in the Goodyear empire, patented the modern standard blimp design with internal suspension curtain-line arrangements.

In general, the "age of the airship" never seems to dawn, in part because the same technological advances that make a dirigible practical also tend to enable airplanes to become more competitive.

However in this period there is a definite advantage that a medium to large size airship enjoys, and that is the matter of range and endurance. Although even the rather primitive airplanes of the era are already three or more times faster than the sky whales, they are of rather haphazard reliability and cannot stay airborne long nor achieve long ranges except as extreme stunts. The first transAtlantic crossing--the easy way, flying with prevailing winds from west to east from Newfoundland to Ireland--was achieved by Alcock and Brown in a Vickers Vimy bomber plane in 1919, but just weeks later, the British R-34 made the second crossing, the hard way against the winds over a much greater distance--starting from RAF East Fortune in Scotland somewhat east of A&B's crash-landing in western Ireland, and flying much farther west than Newfoundland. A&B covered 3040 kilometers in just under 16 hours, but reading about their flight it is evident that their survival was a bit of a miracle, whereas the R-34 made it all the way to Minneola on Long Island, New York. It took them over 4 days, but they covered 4800 kilometers--admittedly they were very nearly out of fuel when they arrived! (But obviously they'd have been fine if they had gone to Nova Scotia, or even Massachusetts, instead. And they did make it to a safe mooring, though just barely). Unlike the near-frozen and miserable pair of A&B, crash-landing in a field in Ireland, they made their goal--I forget just how large the complement aboard was but the article above names at least 5 people aboard, including one stowaway with a dog, and I believe the total was 9 or so. Furthermore upon refueling, the R-34 was well able to return to RNAS Pulham in just 75 hours with ample fuel, going faster and more easily with the prevailing winds.

Now in this ATL, both Britain and Germany are considerably better off than OTL, due to the war ending earlier. The USA never formally took sides. The Zeppelin firm is not trying to operate in a Germany with a collapsed economy nor are they under the ax of a Versailles Treaty regime with the agenda of banning all German aviation.* Neither Britain nor Germany need suffer the extreme stringency of the OTL post-war era though surely both economies will suffer something of a hangover. The rival design firm Schuette-Lanz might also be able to continue in business; with two competing German firms, the chances that airship technology secrets would be dispersed seems more likely. Germany has lost East Africa and all holdings in the Pacific but retains holdings in west Africa, and has gained a vast hegemony in the east of Europe. IIRC German satellites border on the Black Sea and the odds are fairly good that the Kaiserreich enjoys good relations with Turkey. Thus there are potential markets for a German airline even if they find both the French and British firmly opposed to letting them service their colonial holdings or fly over them. The Suez Canal airspace at least ought to remain open; if not passage over the Black sea, over Anatolia and possibly still Ottoman held Mesopotamia might be an option to reach the Indian Ocean--too bad they don't still have East Africa! Nor are there any destinations on the Indian Ocean or beyond that might welcome them--Japan or China being possible destinations but too damn far away going over the sea, whereas Russian airspace is surely closed.

At any rate, I'd think the Germans would want, for reasons of prestige as well as possible revenue opportunities, to establish a regular transAtlantic service. A direct air route to the United States (assuming they are unwelcome in Canada of course) would require diverting around Britain, either south through the Channel in sight of both a hostile Britain and France, or north of Scotland. In summer the northerly route would serve well enough; airships are unlikely to want to operate in stormy seasons (although OTL, in 1960 the USN's Operation Whole Gale demonstrated that blimps could operate and carry out missions in the worst storm season, remaining airborne in weather that grounded airplanes and demonstrating superior endurance and range while detecting all submarines attempting to slip past the gauntlet--it is of course open to question whether 1920s rigids could accomplish the same thing!) They probably could get access to the Azores but unlike airplanes, this would merely be a convenience, not a necessity.

A Zeppelin design postwar, with adequate funding, would be far superior to R-34 (which was not designed as a passenger carrier) and could surely be ready to fly as early or earlier. Despite a longer flight path it ought to be able to take on paying passengers in at least similar numbers to Hindenburg, albeit probably in notably less comfort. But still their comfort would be vastly superior to any possible airplane that could make the crossing by any route. Considering the many stops for refueling a realistic ocean-crossing airplane of the 1920s (if this could be done at all on any scale beyond Alcock and Brown or Lindbergh's near fatal stunts) the speed advantage of the airplane would be largely nullified by long delays waiting for daylight and safe flying weather. The airship just plows on, slowly but majestically, for the most part. I therefore think that in this ATL regular service from Bremen to New York, taking some 4-5 days each way, would be established by say 1922.