Miguel Carlos, Spanish History 6th Edition, 2013, pp. 123-126.

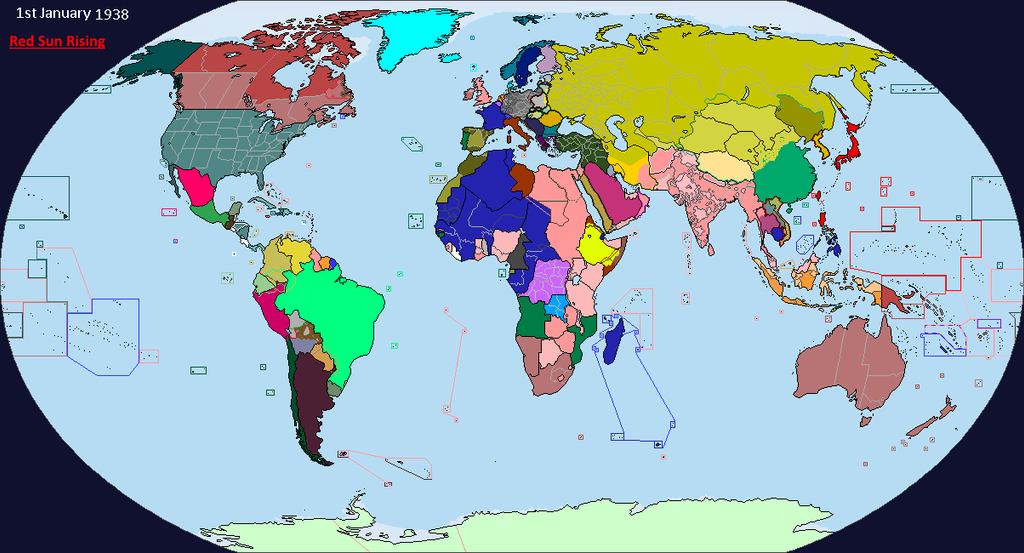

With an alliance with Germany formed and a resurgent France slowly on the rise, The Spanish Kingdom was hard pressed to keep up diplomatic appearances. The victories of the Great War and downfall of competitors created much economic prosperity and prestige. Many felt the wrongs of the Spanish-American war had been corrected. No one seriously believed that Spain could hope to take back the former colonies, but they were investing more in their remaining ones, and that was enough. The autonomy granted to Catalonia and Euskadi helped seperatists in those regions quiet, though groups in the rest of Spain began to become more restless, demanding their own autonomy. Spain's development requires further change.

Ideas for a federation had been around for a while, but it wasn't until 1930 that the idea was finally realised to its full potential. In the meantime, Spain dealt with consolidations in Morroco bringing Hispanic culture and language to the region, something which went to remind many Morrocans of the the Reconquistadors finishing off what they had started long ago. Still, the decision was made to make sure the Morrocans received decent treatment compared to other colonial subjects, as they were the one who would be the most dangerous should colonial rebellions occur like those in France's African possessions. The former principality of Andorra was another point of contest. In June 1925, the former prince the Bishop of Urgell protested regarding the substantial leftist presence in the rest of Catalonia seeping its way into his former territory. The government from Madrid responded by granting aid to the local Catholic churches to continue their missions and involvement in their communities. This improved the situation briefly, but unrest among the radical left was not unheard of. Communists influenced by those in France and Japan were among those dissatisfied by conservative efforts to suppress growing socialist and liberal influence in the former small kingdom. Urgel became a conservative bastion in an otherwise socialist sympathising region of Catalonia. This made any chances of some kind of rebellion problematic, as any socialist rebels would have a thorn in their side, as the pro-German government, while liberalising, was not interested in giving in to socialist demands, especially for radicals.

Further south in Madrid itself, something different was happening. Bread and other foods had reduced in price as a result of the increased amount of food the capital was now able to buy due to the French loans, and so a population boom occurred in Madrid and much of central Spain. With a baby boom and increased migration from the country and around the world, Madrid required growth both externally and internally. This was done via the construction of new modernised suburbs that would house the additional populations, while in the cities, the emphasis on tall buildings capable of housing many individuals became a significant priority. A more densely populated city meant more of a labour force for jobs, and so despite the general moves towards federalisation nationally, Madrid was becoming more important than ever to those living in Castille, as the expanding city was proving to be something that could one day rival Paris or Berlin. In the years 1925-1930, a 17% increase in population came excluding local growth rates, with this surplus being migrations from the countryside to find opportunities in the growing city. The new immigrants would come to influence the political system there as well.

While the conservative party lead by Antonio Maura Montaner and supported by King Alfonso XIII had held the majority of seats for a long time following the Great War and Spanish victory, the influx caused a turn towards the more liberal left. This along with Montaner's declining physical health left many believing that a change in leadership was necessary to lead Spain into the future. Some of the urban workers were republicans who desired the end of the Spanish monarchy and its replacement with a democratic republic of socialist leanings. While they would eventually get what they wanted, it would be many years before this would finally be realised. In the meantime, the liberal party and the socialist party gained seats within the middle and working classes. Among the poorest and most radical members of society grew radical revolutionaries such as anarchists and communists, who wished to not only abolish the monarchy, but completely change the fabric of Spanish society. Moderate liberals and socialists who were willing to compromise with the monarchy were the most accepted however, and so managed to keep the minority groups in check. In the 1928 election, in the wake of the economic crisis in the rest of Europe, a liberal-moderate socialist coalition ousted the conservatives from power and began a more left-leaning era for the Spanish people.

With the rise of the coalition, the powers given to the old nobility were reduced further, and the King's role in the country was pushed toward a ceremonial one, something which angered many conservatives, resulting in a tie between the two spectrums of society. Alfonso naturally opposed the reduction of his influence in the country, and so ultimately the move to reduce royal power was relented by the government. The prime minister was humiliated but continued his work elsewhere. The autonomy acts were soon to build on compensation for the cultural and political divides within the country. Fears of civil war over the increased liberal bias needed to be compensated after all, and so ultimately a decision was made in 1930. In June 1930, the act of Autonomy went through parliament successfully after multiple failed attempts, and so on August that same year, the Spanish Federation was born. Still under a constitutional monarchy in Madrid, the autonomous communities often voted into republics or principalities. Leon, Andorra, Aragon and Galicia were granted principality status while Catalonia, Euskadi, Morroco, Asturias, Cantabria, Valencia and Andalusia were given autonomous republics. This strange mix of monarchism and republicanism regionally intrigued the other powers. Spain's ally Germany was naturally appealed towards the more conservative elements of society, while remaining on somewhat friendly terms with Madrid, at least at the front of diplomacy. The Spanish liberalisation did provide a model for other countries in the Mitteleuropa Pact to follow though, something that would prove of use in the wars to come and their aftermath.

The Spanish Federation therefore struggled through the first couple of years of the 1930s, but did better than many other nations at this point in the economic crisis, doing considerably better than its northern neighbour, at least until Croix's 'Social Action' regime gathered power and control in 1931, whose aims involved regathering lost territories, which would include now Spanish land. When it did, the Spanish Federation felt more and more isolated. Without borders to Germany and Mitteleuropa, a seige mentality began to develop amongst the Spanish people. While Portugal was free to trade with other European powers substantially, and itself slid towards military rule in the collapse of the monarchy before the Great War, it became a crutch to Spain, who tried to remain a bastion of Democracy in Western Europe. Refusal to abdicate Gibraltar from the British further pushed Spain to isolation, though how long this isolation would last would be another question.

With an alliance with Germany formed and a resurgent France slowly on the rise, The Spanish Kingdom was hard pressed to keep up diplomatic appearances. The victories of the Great War and downfall of competitors created much economic prosperity and prestige. Many felt the wrongs of the Spanish-American war had been corrected. No one seriously believed that Spain could hope to take back the former colonies, but they were investing more in their remaining ones, and that was enough. The autonomy granted to Catalonia and Euskadi helped seperatists in those regions quiet, though groups in the rest of Spain began to become more restless, demanding their own autonomy. Spain's development requires further change.

Ideas for a federation had been around for a while, but it wasn't until 1930 that the idea was finally realised to its full potential. In the meantime, Spain dealt with consolidations in Morroco bringing Hispanic culture and language to the region, something which went to remind many Morrocans of the the Reconquistadors finishing off what they had started long ago. Still, the decision was made to make sure the Morrocans received decent treatment compared to other colonial subjects, as they were the one who would be the most dangerous should colonial rebellions occur like those in France's African possessions. The former principality of Andorra was another point of contest. In June 1925, the former prince the Bishop of Urgell protested regarding the substantial leftist presence in the rest of Catalonia seeping its way into his former territory. The government from Madrid responded by granting aid to the local Catholic churches to continue their missions and involvement in their communities. This improved the situation briefly, but unrest among the radical left was not unheard of. Communists influenced by those in France and Japan were among those dissatisfied by conservative efforts to suppress growing socialist and liberal influence in the former small kingdom. Urgel became a conservative bastion in an otherwise socialist sympathising region of Catalonia. This made any chances of some kind of rebellion problematic, as any socialist rebels would have a thorn in their side, as the pro-German government, while liberalising, was not interested in giving in to socialist demands, especially for radicals.

Further south in Madrid itself, something different was happening. Bread and other foods had reduced in price as a result of the increased amount of food the capital was now able to buy due to the French loans, and so a population boom occurred in Madrid and much of central Spain. With a baby boom and increased migration from the country and around the world, Madrid required growth both externally and internally. This was done via the construction of new modernised suburbs that would house the additional populations, while in the cities, the emphasis on tall buildings capable of housing many individuals became a significant priority. A more densely populated city meant more of a labour force for jobs, and so despite the general moves towards federalisation nationally, Madrid was becoming more important than ever to those living in Castille, as the expanding city was proving to be something that could one day rival Paris or Berlin. In the years 1925-1930, a 17% increase in population came excluding local growth rates, with this surplus being migrations from the countryside to find opportunities in the growing city. The new immigrants would come to influence the political system there as well.

While the conservative party lead by Antonio Maura Montaner and supported by King Alfonso XIII had held the majority of seats for a long time following the Great War and Spanish victory, the influx caused a turn towards the more liberal left. This along with Montaner's declining physical health left many believing that a change in leadership was necessary to lead Spain into the future. Some of the urban workers were republicans who desired the end of the Spanish monarchy and its replacement with a democratic republic of socialist leanings. While they would eventually get what they wanted, it would be many years before this would finally be realised. In the meantime, the liberal party and the socialist party gained seats within the middle and working classes. Among the poorest and most radical members of society grew radical revolutionaries such as anarchists and communists, who wished to not only abolish the monarchy, but completely change the fabric of Spanish society. Moderate liberals and socialists who were willing to compromise with the monarchy were the most accepted however, and so managed to keep the minority groups in check. In the 1928 election, in the wake of the economic crisis in the rest of Europe, a liberal-moderate socialist coalition ousted the conservatives from power and began a more left-leaning era for the Spanish people.

With the rise of the coalition, the powers given to the old nobility were reduced further, and the King's role in the country was pushed toward a ceremonial one, something which angered many conservatives, resulting in a tie between the two spectrums of society. Alfonso naturally opposed the reduction of his influence in the country, and so ultimately the move to reduce royal power was relented by the government. The prime minister was humiliated but continued his work elsewhere. The autonomy acts were soon to build on compensation for the cultural and political divides within the country. Fears of civil war over the increased liberal bias needed to be compensated after all, and so ultimately a decision was made in 1930. In June 1930, the act of Autonomy went through parliament successfully after multiple failed attempts, and so on August that same year, the Spanish Federation was born. Still under a constitutional monarchy in Madrid, the autonomous communities often voted into republics or principalities. Leon, Andorra, Aragon and Galicia were granted principality status while Catalonia, Euskadi, Morroco, Asturias, Cantabria, Valencia and Andalusia were given autonomous republics. This strange mix of monarchism and republicanism regionally intrigued the other powers. Spain's ally Germany was naturally appealed towards the more conservative elements of society, while remaining on somewhat friendly terms with Madrid, at least at the front of diplomacy. The Spanish liberalisation did provide a model for other countries in the Mitteleuropa Pact to follow though, something that would prove of use in the wars to come and their aftermath.

The Spanish Federation therefore struggled through the first couple of years of the 1930s, but did better than many other nations at this point in the economic crisis, doing considerably better than its northern neighbour, at least until Croix's 'Social Action' regime gathered power and control in 1931, whose aims involved regathering lost territories, which would include now Spanish land. When it did, the Spanish Federation felt more and more isolated. Without borders to Germany and Mitteleuropa, a seige mentality began to develop amongst the Spanish people. While Portugal was free to trade with other European powers substantially, and itself slid towards military rule in the collapse of the monarchy before the Great War, it became a crutch to Spain, who tried to remain a bastion of Democracy in Western Europe. Refusal to abdicate Gibraltar from the British further pushed Spain to isolation, though how long this isolation would last would be another question.

Last edited: