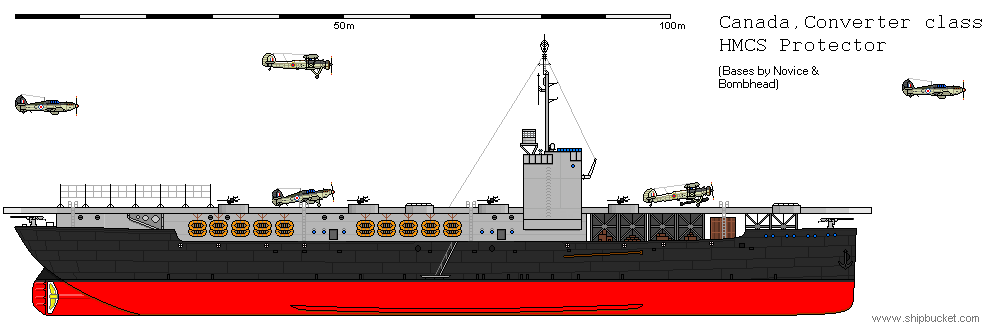

A canadian navy that, before WW2, realized that they would need a way to protect the Atlantic against german u-boat. They bought old freighters and repurposed them into escort carrier, with a dozen planes, a mix of Hurricanes for attack and protection and Swordfish to scout and chase down ennemy submarine. Called the ''converter class'', five of them were planned but at the outbreak of the war, only the Protector (former SS Londonerry) was finnished and combat ready.

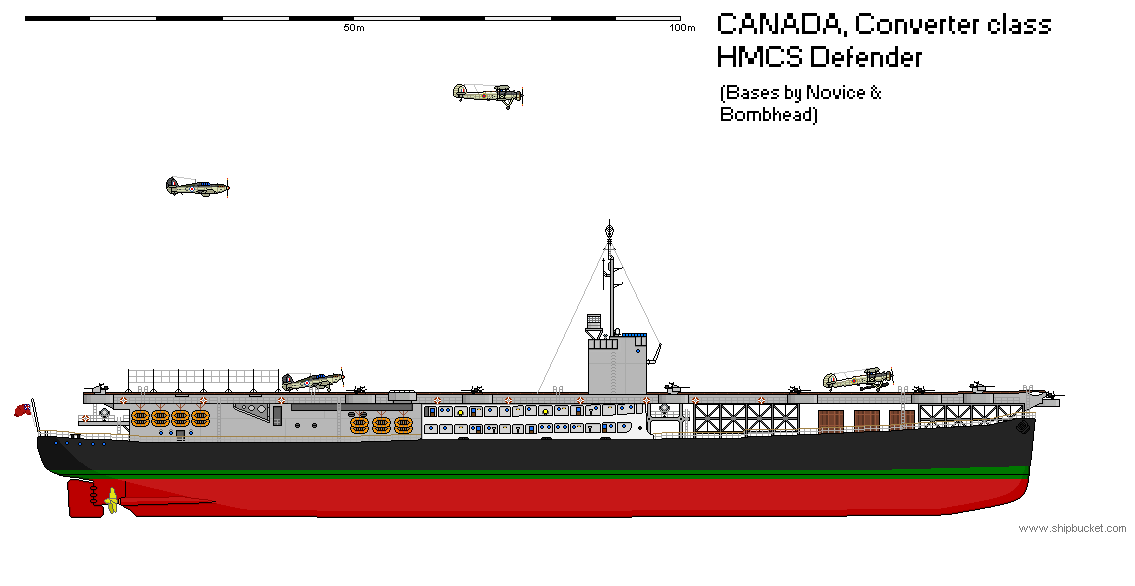

With the lightning fall of France in 1940, the Canadian navy found itself catapulted at the forefront of the war way sooner then they expected. Their Converter-class project, hampered by the lack of funding and adequate ships, fell short of its goal of five converted carriers, with only the HMCS Protector being finished, supplied and combat-ready. The next in line, the HMCS Defender, was still in Halifax's shipyard, stripping the old SS Beaverford from its structure and modifying it into an escort carrier. With the British Isles alone in Europe, they needed all the resources available to continue the fight, and that meant bringing and protecting the vital Atlantic supply line, to keep it open. The HMCS Defender conversion's was accelerated, with the main structure kept and simply strengthen to save time and its crew beginning to train in a ship still in construction.

In mid-october, the ship left its slip, with workers still in board to complete the last details, for a shake-down and practicing its pilots. Around Newfoundland, they spent a week making mock attack on buoy before being recalled in emergency in Halifax. They were to protect the convoy SC-6 from Sydney, Nova-Scotia toward Liverpool. They only had time to refuel and drop the workers before meeting the rest of the escort. Desperately short on escort ship, the Royal Canadian Navy did not had the luxury of keeping one of its rare carriers on sea trial, no matter how vital they were.

All through its career the HMCS Defender would suffer from this, needing no less then three refits, one to modify and strengthen its watertight compartments (that were supposed to also serve as anti-torpedo protection), install dampeners to reduce its engine vibrations (known to affect the fuel lines for the planes, many of their screws and joints suffered) and even ballast to compensate for its top-heavy structure.

Nonetheless, like the HMCS Protector, the HMCS Defender would prove, with its Hurricane/Swordfish mix, to be a deadly opponents for the German u-boats. So vital to the safety of convoy, Converter-class carriers were often reserved for the most important cargo, such as fuel and foods.

In 1933, the former SS Astrée of the Compagnie de Caen was put to sell and both Canada and Italian owners were bidding for the ship, for two different reasons. The Italian bidders were obviously looking to own the ship for cargo hauling but the Canadian government was looking to convert the ship into a potential escort carrier. The Canadian government finally won the ship and made it cross the Atlantic to reach Halifax. While the construction slip was already occupied by the former SS Londonberry and the SS Beaverford being inspected and cleaned, the SS Astrée waited in a dry dock of the Halifax Shipyard of the Dominion and Steel Corporation while funds were made available. While inspector reviewed the ship structure and small repairs and maintenance took place, it was not before 1936 that the Astrée finally shed its civilian skin to wear its military identity as the new HMCS Escorter when the HMCS Protector (ex-Londonberry), was finally completed.

But the Converter-class program was always low on funds and priority, many politicians dragging feets when it came to spending more money on carriers, especially due to both the need in airplanes, pilots and sailors, many preferring investing in cheaper Corvette and Frigates. Especially as the old structure of the Protector meant that many refits were needed, workers from both the Defender and Escorter were frequently transferred to save cost. In 1939, the HMCS Defender was 70 % completed while the Protector had only its interior redesigned when the war was declared. The Phoney war and the lack of apparent menace meant that the pace was not accelerated, in fact, the Canadian navy gearing up for war meant refitting or readying many old ships, competing with the two soon-to-be carriers. With the fall of France and the ''convoy panic'', all the efforts were transfered to the Defender to make sure that she would enter service as fast as possible, meaning that the Escorter's workers were transfered to help.

With the Defender launching in 1940, efforts focused back to the Escorter and even new potential ships. In June 1941, the ship would launch and do many sea-trials before being considered ready for operations in late October. Thanks to the lessons learned from both carriers (especially the Defender numerous refits), the HMCS Escorter would be considered as the most advanced first generation Converter-class carrier. The munitions and spare parts crates were finally removed, a catapult was installed and the armament fixed to 8 single-mount 20mm and 4 single-mount 40mm Bofors (the old 4in gun, already absent due to a lack of space on the Defender, were abandoned since the main threat was isolated as either submarines or aircraft).