All true. But we also have to consider that the losses in WWI also tailored german strategy in WWII. Blitzkrieg was basically a textbook example of people responding to the problems in the last war, and immediately overcompensating. Germany knew they didn't have the manpower to throw forever at problems either.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

To the Victor, Go the Spoils (Redux): A Plausible Central Powers Victory

- Thread starter TheReformer

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 45 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Map of Europe as of the signing of the Treaty of Zurich Social Conflict & Elections: France (August 1918 - May 1919) The Italian Civil War (December 1918 - January 1919) Social Conflict & Elections: The United States (October 1918 - January 1920) The Habsburg Reckoning I (September 1918 - February 1919) The Russian Civil War | The Whites Advance…? (October 1918 - March 1919) The New Ummah | The Second Arab Conquest (October 1918 - December 1919) The New Ummah | Ottoman Woes (November 1918 - June 1919)It's confusing why the IPP got more seats than OTL, the party was a spent force at this point and I don't see any reason for it to change in this TL.

Social Conflict & Elections

Britain

January 1919

British society had emerged from the war profoundly changed. Strengthened by the need for constant and high-output industry, key sectors of the economy had become vital to the war effort in the absence of many men fighting, and thus the power of mining and manufacturing unions had greatly increased.

Unlike most states in Europe at the time, Britain’s experience with political socialism had not been built off the back of academia, but unions. In France for example, there were multiple Socialist parties. This was also true of Germany where their unions had, on instruction of their political leaders, just forced Germany into political concessions. In Britain though, Labour was a party that was made up of a collection of political bodies including the trade unions, and intellectual ‘think tank’ groups like the Independent Labour Party and the Fabians.

Far from a revolutionary party, Labour had supported the Government during the war but had left the coalition when it became clear that the loss of Amiens had proven too much for the British war effort on the continent. Party leader William Adamson, a firm trade unionist from Scotland, led a party that still felt deeply divided over the value of the war. What they were united on though was the belief that Britain should end the war and that she should not engage in imperialism any further.

For most working class Britons these policies seemed very reasonable, if the war in Europe was essentially lost, why continue to lose soldiers elsewhere? This after all was a war against Germany, who had attacked Belgium. Everyone else, in their eyes, was an afterthought. Even after Gallipoli the British public had learned to hate the Turks, but only as much as they despised the men who screwed the pooch on the operation’s plans.

Despite this, the war had continued and relations between Britain’s social classes had rapidly declined. By the time negotiations for peace with Germany began, there were very real signs of unrest in the Rhondda valley, Manchester and the Clyde. These were the heartlands of the ‘triple alliance’ trade unions; the National Transport Workers' Federation, National Union of Railwaymen and the Miners' Federation of Great Britain.

These three unions alone had the capability to cripple British infrastructure if they had wished, but despite the more revolutionary attitude of the Independent Labour Party, who had opposed the war and were spurred on by Italy’s strife, direct action never took place. This was in part precisely because of the fears of an Italian style state schism.

This changed though in January 1919. Since the defeat in France, many British soldiers had been simply demobilised and returned to Britain. This had prompted a rapid rise in unemployment as these soldiers returned to a nation where their jobs had been filled by other men or even women. Unions thus proposed that the working week be reduced to 40 hours for every worker to provide more hours overall for more workers and share the burden.

This policy was widely supported in the ‘red’ regions of Britain, notably on the Clyde, in Manchester and Rhondda valley in Wales. In Glasgow though, this would take a bad turn. On January 27th, around 3,000 striking workers opted to meet at the St. Andrew's Halls. Just three days later though these numbers would swell to the tens of thousands as the city’s shipbuilding and engineering workers joined.

Police soon sought to crack down on the protesters, and thus when on January 31st a large congregation of tens of thousands of protesters met on George square, police immediately charged the workers to disperse them. In what became known as the ‘Battle of George Square’, the workers in their anger and frustration at the war and the further declining economic situation, actually fought back and ‘won’ the battle. Police forces were driven off and the fighting spread into the surrounding streets.

During the fighting, representatives of the workers had been meeting with the Lord Provost of Glasgow at the city chambers. Immediately upon hearing of the violence they went to leave, but were set upon by police after leaving the building. CWC leaders David Kirkwood and Emanuel Shinwell, along with Trade Unionist leader Willie Gallacher, were all arrested and detained - enraging the protesting workers who soon descended upon the city council building where they were being briefly detained.

Here, the protesters eventually managed to storm the building and compel the release of their leaders. Gallacher, who had been jailed repeatedly, then turned the strikers to march on the barracks in the Maryhill district of Glasgow. Here, thousands of workers surrounded the complex and began calling on the soldiers to join them.

Demoralised and generally sympathising with the strikers demands on better hours and pay, the soldiers of the barracks remarkably arrested their commanders and joined the now armed protest. Thankfully, by then the Government had already met and ordered the dispatch of 12,000 soldiers to Glasgow to prevent any ‘bolshevist incident’ from taking place.

Joined by six tanks, the large force quickly took control of Glasgow railway station in the night and deployed in force. While strikers had been furious, and soldiers at the local barracks had gone over to the other side, the reality was this protest had never been an attempt at revolution. Overnight the rioters had, unsurprisingly, gone to bed - save for a few radicals - and thus the crisis came to an abrupt halt.

Simply getting ahead of themselves and acting to protect their own interests, the protesters soon abandoned the idea of actually fighting for control of the city even if they implicitly controlled it for several hours and their mutineering soldier allies largely just slowly melted back into their barracks in the face of the overwhelming army presence.

The close call of the strike sent shockwaves through the British establishment. Genuinely confident that a major strike by the triple alliance of British trade unions would topple the Government, the Prime Minister soon met with the heads of the three unions together to discuss the political situation.

Not revolutionaries, railway workers union leader Jimmy Thomas even spoke in Parliament against unofficial and wildcat strikes, saying: “However difficult an official strike may be, a non-official strike will be worse, because there is always the grave danger in unofficial strikes of no one being able to control them”. Such was the strength of feeling against action that could undo the stability of the state that even Trade Union leaders cautioned against it.

Fearful of similar or even worse incidents elsewhere, Bonar Law finally felt compelled and comfortable enough to end Britain’s wartime measures and call fresh elections set for February 1919. This allowed the unions to deliver a rallying cry for major financial and time committed support for Labour at the polls, lessening the chance of strikes and thus reducing the chance of a revolutionary incident. In this backdrop, the country entered a rather tense and uncertain election season.

The 1919 Election

The first election in over eight years, the 1919 election was a woefully overdue poll that would reshape British politics.

The Tories under Bonar Law entered the voting with 271 seats - 53 short of a majority having been propped up by the weakened National Liberals (now Coalition Liberals) out of a desire for self preservation more than anything else. Despite the chaotic period of his premiership, Bonar Law was widely sympathised with among the middle classes and elite cadres of society, winning over swathes of Liberal voters who were impressed by Law’s victory over the Ottomans and deft negotiations with Germany where both Asquith and Lloyd George had failed.

Labour meanwhile looked set to win their greatest number of seats yet - and were very genuinely touted in the press as possibly being on the verge of taking power altogether. This was either scaremongering or naive optimism though among the media establishment. Sure, one would not struggle to find a labour voter on the streets, but in reality the country was ready for change - but not that much change.

Ironically though this worked against the party, who were unfairly portrayed as being bolshevik adjacent with their platform aiming at nationalising the mines and railways under leader William Adamson.

The Liberals meanwhile looked set to be decimated. Deeply alienated from their voters by Asquith and Lloyd George’s double flunking of the war, many Liberal voters had abandoned the party for the Tories. Still headed by a naive Asquith who sought to ‘ride out’ the near-certain defeat at the coming poll, the party stood on a platform aimed at more radical political and social reform in a bid to win over wavering middle class Labour voters, but in reality few trusted the party anymore. Ironically they expected poor results - with Asquith’s close ally Donald Maclean actually favouring the idea of a pact with Labour to shore up voters, though Asquith didn't believe the effect of a ‘khaki’ election would be so severe and rejected the idea.

The formerly National Liberals meanwhile still propping up the Tory ministry under Bonar Law, notably including figures like Churchill and even Lloyd George - though politically he remained a shadow of his former self. Identified mainly as ‘Coalition Liberals’, this bloc generally campaigned on the Tory platform and piggybacked off their voters. Now led by Churchill, who was frankly one of the last prominent National Liberals left, the party initially sought reconciliation with Asquith’s liberals for a united campaign but ultimately proved unable to dislodge Asquith from his position in the party. While the rift was healable, that would have to wait for the end of the war.

The overwhelming sense among the public was that a change was needed, but the most important change needed was stability. After years of mixed coalitions of various parties and blocs, the country needed one party in power with a clear agenda and competence in Government - and the obvious choice therefore was the Tories.

The Tories also benefited from the unexpected and remarkable rise of Britain’s ‘lost boys’ - roving bands of demobilised soldiers named for their similarity with the characters of 1911 classic ‘Peter Pan’. These troops had escaped confinement upon disembarkation in Britain’s ports and service in the army still with their uniforms and/or arms, and used them to engage in criminal activity and begging on the streets of Britain’s cities.

Somewhere between brigands and beggars, they were reported across the country but were particularly concentrated in the south and major ports of the country where demobilised troops often disembarked. Often pushed by a lack of jobs and general apathy or uncertainty, the lost boys became a political issue during the buildup to the election after the roaming groups caused a steep rise in crime throughout Britain’s cities.

Seen as not easily controlled by police and technically out of the army, and where not armed therefore not the army’s problem, the mobs could be found in ‘units’ as large as whole platoons in some cases. This was primarily because the troops often had not found work and found the prospect of a return to normal civilian life daunting or difficult.

While the lost boys tended to be unofficial criminal mobs, some soldiers and veterans mobilised their own politically oriented groups during late 1918 to early 1919. Groups such as the Labour allied National Association of Discharged Sailors and Soldiers (NADSS), which excluded officers, and Conservative allied anti-socialist Comrades of the Great War could often be found ‘sparring’ in the streets in debate - or more often just straight yelling matches.

These were not paramilitaries or militias, but they acted as increasingly large, politically hostile bodies of men attached to their respective parties. Their disagreements mostly stemmed over the continuation of the war and the terms of the peace. The NADSS and Labour primarily opposed the terms with the Ottomans as an entrenchment of imperialism, along with the annexation of German colonies, while the Comrades of the Great War tended to back Bonar Law’s seeing through of the conflict to the end and the focus on the middle east.

A debate also raged over the role of Britain in Russia’s ongoing civil war. British troops had landed in Arkhangelsk in Northern Russia in March 1918 as part of an attempt to prevent Bolshevik troops from seizing one of the allies’ major arms dumps in the city. Now nearly a year on, a debate continued to rage over what exactly the allies were doing there. While the National Liberals under prominent jingoists like Winston Churchill still called on a British intervention in Russia to establish a ‘stable friend to the east’ as a check on Germany by installing the Russian whites, the Government had grown increasingly ambivalent about the whole situation.

In some cases the emergence of these groups even directly affected the ballot box, with the left-liberal National Federation of Discharged and Demobilised Sailors and Soldiers (NFDDSS) becoming the most cohesive political bloc and standing thirty candidates in the election.

Focused on military pensions, opposed to re-conscription and tentatively allied with the Labour Party, the group drew a remarkable number of left-Liberal Party MPs backing including prominent Asquith-ite Liberals James Hogge, William Wedgwood Benn and William Pringle. Hogge was a rising player in the Liberals and save for Asquith’s endless determination to go on and on, he may have become sooner party leader. This allowed the group to gain some considerable support from frustrated former Liberal voters and propelled them into a position where they could win multiple seats.

Alongside these ‘soldiers parties’ also came a slew of other new parties, most notably the National Party under Henry Page Croft which entered the election with 7 MPs due to Conservative Party defectors. Page Croft, a protectionist imperialist with a military record who despised Germans, led the party on a policy of ‘total victory’ over Germany and a bizarre working class ‘patriotic’ appeal in a party largely dominated by the aristocracy. Supporting ‘no limits on wages’ in exchange for ‘no limits on production’, the party even briefly offered to back Labour, seeing it as the future of politics - despite its deeply divergent political views.

There was also Ireland of course. Now one might have initially assumed that the ‘defeat’ to Germany would have ignited some kind of powder keg in Ireland immediately, but in actual fact the buildup to the Irish revolutionary period was slow, gradual and far less dominated by the radicals in Sinn Fein than one might assume. If anything, Sinn Fein was marginally weakened by Germany’s victory indirectly.

The sudden rise in the popularity of British Labour in fact convinced the party that it could win seats in Ireland. As such, where before leader William Adamson had planned to let Sinn Fein run free in Ireland without splitting the worker vote, he now chose to try and bolster his own party’s seat count and take the position of the official opposition. As such, Labour would run candidates in Ireland, putting Irish working class voters in something of a bind.

Nationalism in Ireland was without a doubt a minority view. While very popular, there was no landslide majority for independence in 1918 even after the conscription crisis. Working class voters in many of Ireland’s cities for example put more emphasis on the class struggle than that of the national struggle with the British, and thus where historians have speculated Sinn Fein may have won as many as 73 seats without Labour, in actual fact by election day they were looking at around ten fewer.

Naturally, the nationalists had not sat on their hands throughout this period. Sinn Fein had made clear that the path forward for Ireland was independence, or at the very least its own Parliament - and thus they promised exactly that. Come election day, they would promise not to take any of their seats in Westminster, and instead to form their own Parliament in Dublin.

The Results

The results after a short and somewhat tense campaign were clear. The Liberals, the party of Government at the start of the war with 272 seats, were reduced to just 37 seats after suffering a heavy split between Lloyd George’s and Asquith’s camps. The former ‘national’, now Coalition Liberals of Churchill and Lloyd George would take 43 seats. Embarrassingly, Churchill himself actually lost his seat to Edwin Scrymgeour of the Scottish Prohibition party - leaving the leadership open yet again. Asquith too was ousted in his Fife East seat by Scottish Unionist Alexander Sprot.

Labour meanwhile performed the best of any poll to date, but unsurprisingly failed to suddenly take power as some papers and political ‘observers’ predicted. Taking 119 seats and with it the mantle of the official opposition, along with over 25% of the national vote share. Quite the shock to some in the country, Adamson himself hailed that the result would “produce a different atmosphere and an entirely different relationship amongst all sections of our people”.

The biggest winner of the election though were, unsurprisingly, the Tories. Winning a total of 391 seats in the Unionist Camp, including the Scottish, Irish and Labour Unionist parties under the Tory umbrella. Bonar Law was now unquestionably the Prime Minister of the country for the time being - and held the largest majority since Henry Campbell-Bannerman’s premiership in 1906.

Now no longer in need of support from the Coalition Liberals, it quickly became clear to everyone that despite their best hopes, David Lloyd George’s half of the party would not be involved in this Government - sealing his political demise for good. Together still on 80 seats, the two Liberal halves would begin the process of healing the national rift soon after thanks to the demise of Asquith, though naturally this would take some time.

Elsewhere there were some surprising victors. The Nationals in their limited numbers managed to maintain five of their seven seats prior to the poll, demonstrating surprising staying power. Christabel Pankhurst, daughter of women's suffrage movement leader Emmeline Pankhurst, won the election in Smethwick and became Britain’s first ever woman MP - joined by Constance Markievicz of Sinn Fein, who never took her seat and is thus discounted. The NFDDSS too would snag seats, winning in Ashton-under-Lyne, Clapham and Liverpool Everton.

Meanwhile in Ireland, Sinn Fein would win overall with 63 of Ireland’s 102 seats. This would have two main effects; it would greatly enlarge the Government’s de facto Parliamentary majority, and pivot Irish politics towards eventual independence. The Irish Parliamentary Party meanwhile would take 15 seats, down from 74 prior to the election. Still alive, but barely clinging on, albeit without their leader John Dillon who would be defeated in his East Mayo seat.

In all, the results would greatly re-shape British politics and return some normality to the country after the war. While the country faced many challenges, particularly financial, the Government’s large majority would provide the country with stability and give Bonar Law a solid opportunity to re-establish Britain’s place at home and abroad.

Labour could take a few seats from Sinn Féin (OTL the Democratic Programme of 1919 was drafted as a sop to the Irish Labour Party in exchange for them not standing, though Republican leaders like Collins and Brugha made clear their contempt for it in private) but socialism and the idea of class conflict had little influence in the very conservative Ireland of this era, the likes of James Connolly and the ICA were always a small minority and the Labour Party had to majorly downplay how left-wing they were to not be wiped out in elections.

Last edited:

Defeat in the war does not automatically mean that all political views in the country become "screw Britain". Unfortunately people have a perception that defeat of any single major power in the Great War would mean that all OTL seperatist movements and radical movements (socialists in France for example) would be greatly inflated, whereas in actual fact the effects would of course inflate some - but not all. This I suspect is a consequence of Germany's loss of lands to the Poles, which was more a consequence of the German army being dismantled by force, and Austria's total collapse, which was a consequence of Austria Hungary's unique circumstances. Not to mention - Britain was not defeated, France was. There was Russia too - but again, different circumstances.It doesn't make much sense Sinn Féin to do worse than OTL, the defeat of Britain in the war would absolutely encourage Irish nationalism, and it's confusing why the IPP is still alive and kicking, the party was a spent force at this point OTL and I don't see any reason for it to change in this TL.

Ireland was something of a unique case in the modern era. The Easter rising was initially a rather unpopular move, and the vast majority of the Irish population did not seek such a radical outcome. Of course the fact the rising was so heavily crushed, notably by primarily Irish troops, did not play well on the conscience of many Irishmen - understandably giving credence to the vuiews of the radicals. However, it's worth noting that hundreds of thousands of irishmen volunteered for the war, and most frontline troops opposed the rising, according to Pandora's Box - Jorn Leonhard, Patrick Camiller. It was conscription that really gave Sinn Fein it's strength, and ittl the effects of conscription are heavily dampened due to the collapse of the western front months before OTL.

As for the IPP, it is no more alive ittl than it was irl. The key difference is that ittl, Labour competes in Ireland whereas irl they did not, splitting the vote in specific seats and delivering a 15 seat result for the IPP rather than their 7 seats as per OTL. They do this entirely because of the war, which inflates the party's chances of taking power of the opposition - thus meaning they run in Ireland and even if they win just 5% in some seats will naturally stop Sinn Fein winning them.

I'm fully aware of this fact, however it seems contradictory to me that you are on the one hand saying Sinn Fein voluntarily adopted a Democratic Programme to placate would-be Labour voters they needed, while also claiming that there were very few socialist Irish voters.Labour could take a few seats from Sinn Féin (OTL the Democratic Programme of 1919 was drafted as a sop to Labour in exchange for them not standing, though Republican leaders like Collins and Brugha make clear their contempt for it and Labour in private) but socialism and the idea of class conflict had little influence in the very conservative Ireland of this era, the likes of James Connolly and the ICA were always a small minority and Labour had to majorly downplay how left-wing they were to not be wiped out in elections.

Regardless, I'm not intentionally downplaying the success of Sinn Fein, the party does better here vote wise than it does IOTL - before you subtract the would be Labour voters. My Irish friend @Gonzo assisted with the seat calculations though, so he probably could probably break the numbers down a little better.

Last edited:

I later edited that comment but regarding a British defeat encouraging nationalism it's less viewpoints changing to "screw Britain" and more that Britain's defeat would encourage people who have underlying nationalist sympathies but felt that the chance of successfully getting independence from Britain normally was impossible or unlikely.Defeat in the war does not automatically mean that all political views in the country become "screw Britain". Unfortunately people have a perception that defeat of any single major power in the Great War would mean that all OTL seperatist movements and radical movements (socialists in France for example) would be greatly inflated, whereas in actual fact the effects would of course inflate some - but not all. This I suspect is a consequence of Germany's loss of lands to the Poles, which was more a consequence of the German army being dismantled by force, and Austria's total collapse, which was a consequence of Austria Hungary's unique circumstances. Not to mention - Britain was not defeated, France was. There was Russia too - but again, different circumstances.

Ireland was something of a unique case in the modern era. The Easter rising was initially a rather unpopular move, and the vast majority of the Irish population did not seek such a radical outcome. Of course the fact the rising was so heavily crushed, notably by primarily Irish troops, did not play well on the conscience of many Irishmen - understandably giving credence to the vuiews of the radicals. However, it's worth noting that hundreds of thousands of irishmen volunteered for the war, and most frontline troops opposed the rising, according to Pandora's Box - Jorn Leonhard, Patrick Camiller. It was conscription that really gave Sinn Fein it's strength, and ittl the effects of conscription are heavily dampened due to the collapse of the western front months before OTL.

I'm aware of the history, though I've seen it debated more recently whether sentiment for Home Rule was genuinely all the Irish people wanted or rather the most that they thought was feasible at the time (which ties into my point above a bit). The thing about Irish troops volunteering is true (John Redmond encouraged Irishmen to fight in the war to secure Home Rule) although it should be noted that recruitment in Ireland slowed down after the first year, though the Easter Rising and especially the conscription crisis did definitely change things. The British government's proposal during the conscription crisis that Ireland would be granted Home Rule in exchange for accepting conscription was particularly harmful for public perceptions of it and the IPP.

Ah, that makes more sense.As for the IPP, it is no more alive ittl than it was irl. The key difference is that ittl, Labour competes in Ireland whereas irl they did not, splitting the vote in specific seats and delivering a 15 seat result for the IPP rather than their 7 seats as per OTL. They do this entirely because of the war, which inflates the party's chances of taking power of the opposition - thus meaning they run in Ireland and even if they win just 5% in some seats will naturally stop Sinn Fein winning them.

I'm not being contradictory, it was to placate Labour leaders so the party wouldn't run against Sinn Féin and split the vote, not voters. The Democratic Programme was released in 1919 after the 1918 general election after all.I'm fully aware of this fact, however it seems contradictory to me that you are on the one hand saying Sinn Fein voluntarily adopted a Democratic Programme to placate would-be Labour voters they needed, while also claiming that there were very few socialist Irish voters.

Regardless, I'm not intentionally downplaying the success of Sinn Fein, the party does better here vote wise than it does IOTL - before you subtract the would be Labour voters. My Irish friend @Gonzo assisted with the seat calculations though, so he probably could probably break the numbers down a little better.

Last edited:

Ah yes you're quite right there, got my dates confused between the OTL 1918 election and ITTL's 1919 election lolI'm not being contradictory, it was to placate Labour leaders so the party wouldn't run against Sinn Féin, not voters. The Democratic Programme was released in 1919 after the 1918 general election after all.

Anyway, main thing really is that ittl Sinn Fein getting fewer seats would not really have any dissimilar impact to OTL. Sure, ittl Sinn Fein does slightly worse seat wise. But the sentiments still exist, the issue still remains and, as you say, the war did not go Britain's way - even if they didn't really 'lose' either. As such, Sinn Fein's shockingly good result would likely be met very similarly ITTL to OTL, as the people of this timeline don't consider the fact they could have done better without Labour etc.

Thus in Ireland the political situation is very similar, if not more or less identical to OTL atm.

Last edited:

Not to mention - Britain was not defeated, France was.

But you did say otherwise in your Georgette post.

Britain, even if it didn’t know it yet, was defeated.

But I think I know what you meant: Michael and Georgette were serious tactical reverses for the British Army, but it doesn't mean they could be said to have lost the war, at least not in the way the French did. (Certainly not when you look at the treaty outcome!)

Defeated on the field =/= Defeated in the conflict etc.But you did say otherwise in your Georgette post.

But I think I know what you meant: Michael and Georgette were serious tactical reverses for the British Army, but it doesn't mean they could be said to have lost the war, at least not in the way the French did. (Certainly not when you look at the treaty outcome!)

As you say!

Defeated on the field =/= Defeated in the conflict etc.

As you say!

I think the danger is, it's gonna feel like a defeat to an awful lot of Britons, though.

Exactly. France like post WW2 Germany has lost twice and been physically devastated.But they lack the ability of Germany to so quickly build a fighting force to tear through Europe. Losing the briey-longwy mines will put a sizable dent in the French economy and war-making capabilities, even without reparations and debt to the allies. There is also the psychological effects of this being the second war in little over half a century that France has lost to Germany, and that Germany, with the eastern puppets and western annexations, is stronger than ever. If the soviets are somehow occupying Berlin, I’m sure the French would jump to grab the lost lands, outside of that though I just can’t see it.

someone on here said it before, but I can’t remember who. But that France would be more similar to Germany post-WWII, than Germany post-WWI, still a strong nation, still capable of a vibrant economy, still able to throw around its weight with money, but unable to militarily exert its will on its immiediate neighbors.

As for Britain, the situation is a bit better for revanchist ideology but they still don’t have economic devastation/reparations. Plus Britannia still rules the waves and a shitton of colonies

Last edited:

... I wonder ... what do you actually render as "Austro-Polish Solution" ?This is plainly incorrect. The Austro-Polish solution ...

The according literature - including the sources you name - see the difference in the territories assigned to though these changed over the course of time and negotiations on the german side (germano-polish solution) as well as on the austrian side (austro-polish solution). ... tried to hint at in my post above.

It was never a discussion of the provenance of a possible king of german or austrian nobility rather some internal austrian discussion.

... strangely according to your sources an austro-polish solution - terrotorial - was still discussed well past midth of 1918 (like July and August) as you might be able to find - aside other sources - in chapter 19 f.f. of 'esteemed' Fritz Fischer.... was over by mid, if not early 1918 ...

Without a doubt but ... this has nothing to do with the topic I put to discussion:... and Austria was forced to make massive concessions to Germany throughout the last year of the war both economically, politically and even diplomatically - including a commitment to joining Germany's planned Mitteleuropa. ...

provenance of a possible polish king and its discussion between the CP.

I would recommend revisiting at least your named sources (or rather single source as the according entries on the 1914-1918 encyclopedia online are more or less based on Fritz Fischer and his disciples like Moonbauer and Geiss who between them more or less citing/copy 'n pasting each other).This is backed up both by research conducted on the 1914-1918 encyclopedia online, and also Germany's War Aims in the First World War - Fritz Fischer, which explicitly states this to be the case.

On attentive reading you might find out that aside enumerating esp. by very selected outlyers wishfull pipedreams, dysnastic fairy tales of Kaiser Bill in his more maniac and less depressive phases as well as the megalomania of a late Ludendorff at least Fischer doesn't fail to acknowledge that these were all the time opposed - and to a large extent succsessfully. Rarely were they realized - at least laid down in diplomatic 'agreements and papers' by the 'politicians' as the civil part of the "Reichleitung" (realms leadership).

Also ... the "austro-polish" or "germano-polish" solution when mentioned was always about territories (aside some rather general undetailed mention of Kaiser Bills dynatic mindblobs). There's no mention of certain houses or nobel families to take a polish throne esp. not as a matter of discord between the german and the austrain side. Only 3 times Archduke Karl Stefan is named in Fischers book as a sole pretender for the polish throne.

(In general ... though Fischer added quite a 'bibliography' to his (IMHO sorry) work he all too often failed to differentiate in his writing when and where he 'cites' whatever source or simply interpretes the parts he selected from shis sources to fit his own perception and interpretion of history.)

... now for more ... interpersonal perceptions ... ?

... let's see ... lack of information ......

I disagree with this assertion, and don't particularly see how I am doing so. Dont cast asperions on the plausibility of my timeline on the basis of your own lack of information. ...

Aside the sources you've named I founded my comment on several primary sources like the remembrances, diary entries, letters etc. of Bethmann-Hollweg, Kurt Riezler, Erich v.Falkenhayn, Hans v.Plessen, Richard v.Kühlmann, Georg v.Müller, Alfred vTirpitz, Albert Hopmann, Richard v.Kühlmann, Paul v.Hintze, Franz Conrad v.Hötzendorf as well as their reception by historians as Holger Afflerbach or Holger Herwig as well as i.e. the latters or edited collections esp. on "The Purpose of the First World War" as well as monographs of several historians as Richard W.Kapp, Aliaksandr Piahanau, Marvin Benjamin Fried, Jens Boysen, Manfried Rauchensteiner etc. aside at least a dozen article on the topic plus articles on neighouring topics.

I would render both our amount of 'lack of information' at least on par.

If you can't stand critizising critics aside praising critics you should have better published not in a forum its headline contains specifically the word "DISCUSSION"It's demoralizing, ...

Something that should be expected if someone labels his work with specifically this attribute... and not the first time you've specifically referenced 'plausibility'...

I didn't know that such statements are empowering supression of general human rights as freedom of Speech and Thought.... despite the OP explicitly stating not to do this.

Not at least as you've made it a rather important trigger for following events.

If you can provide some source indicating a plausible possibility that the german Reichsleitung considered at some point to install some german princeling esp. in the late phases of the war) on the polish throne ...

nobody would be better of than me.

But all the sources I've come across so far ... don't hint at all at such a possibility (not to talk even of probability).

Last edited:

As for Britain, the situation is a bit better for revanchist ideology but they still don’t have economic devastation/reparations. Plus Britannia still rules the waves and a shitton of colonies

It's got about £7 billion in additional national debt, though... And much of it was owed to the Americans. (Geddes and Baldwin are going to have so much more fun negotiating that in *this* timeline!) We might be able to shave off a little of that, since British combat operations on the Western Front end by July, rather than November, but since full mobilization was maintained...probably not *too* much.

Worse, it won't be getting any reparations from Germany this time, and because it will be forced to maintain the Navy (and, uh, a nascent air force) on a larger scale, there won't be near as much of a "peace dividend."

But probably the greatest pain will be the horrific casualties they sustained, and sharper questions about whether it was worth it. Your school chums are all dead, the zeppelins blew up your uncle's flat in Rotherhithe, and yet the Hun is now running Europe. The fact that His Majesty is now sovereign of a bunch of New Guinea headhunters and unhappy Marsh Arabs probably won't feel like much consolation. No one can pretend that this was a war to end all wars, and the way this war was sold* - and bought into - on the British homefront is, I suspect, going to make it feel like a real failure, no matter how deft Whitehall's diplomats were in Copenhagen.

____

Cécile Vallée has made an compelling case that British anti-German propaganda in WW1 was a good deal more vicious and ill-humored than its WW2 propaganda, which sounds unlikely and counterintuitive to us today; but the weight of the evidence suggests that it's true to a large degree.

Last edited:

If this is the case then, frankly, you're not looking.If you can provide some source indicating a plausible possibility that the german Reichsleitung considered at some point to install some german princeling esp. in the late phases of the war) on the polish throne ...

nobody would be better of than me.

But all the sources I've come across so far ... don't hint at all at such a possibility (not to talk even of probability).

I'm at my parents at the moment as it running up to Christmas, so I'm not going to go and photograph the page of the book I have specifically referenced for you - it's in my flat. So, instead I'm going to demonstrate how utterly little research you have evidently put into this claim.

Here's information on how ill-fated the Austro-Polish solution (which btw, is exactly the solution you are describing with Archduke Charles Stephen of Austria taking the throne) was by 1916, let alone 1918. This is from the accursed wikipedia...

Of the candidates for the new Polish throne, Archduke Charles Stephen of Austria (Polish: Karol Stefan) and his son Charles Albert were early contenders. Both resided in the Galician town of Saybusch (now Żywiec) and spoke Polish fluently. Charles Stephen's daughters were married to the Polish aristocrats Princes Czartoryski and Radziwiłł.

By early 1916, the "Austro-Polish Solution" had become hypothetical. Erich von Falkenhayn, the German Chief of the General Staff, had rejected the idea in January, followed by von Bethmann-Hollweg in February. Von Bethmann-Hollweg had been willing to see an Austrian candidate on the new Polish throne, so long as Germany retained control over the Polish economy, resources and army.[15]

German candidates for the throne were disputed between the royal houses of Saxony, Württemberg and Bavaria.[16] Bavaria demanded that their Prince Leopold, the Supreme Commander of the German forces on the Eastern front, become the new monarch.[17] Württemberg's candidate Duke Albrecht was considered suitable for the throne because he belonged to the Catholic line of the house.[18] The Saxon House of Wettin's claim to the Polish throne was based on Frederick Augustus I of Saxony, who was made Duke of Warsaw by Napoleon during the Napoleonic Wars, and also to the election of Augustus II the Strong as the King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania in 1697.

Naturally the book I have referenced, Germany's Aims in the First World War by Fritz Fischer, goes into far more detail and outlines how essentially by the final year of the war Austria had become so reliant on Germany, Germany's political elites and military command considered it almost a joke that Austria thought they had any chance at getting their candidate selected.

Germany had no desire to see Poland in an Austrian 'sphere', and it's foreign policy elites by 1918 essentially forced Austria to accept there would not even be an Austrian sphere. Poland was critical to Germany's plans for a security buffer against Russia in the east. They were unwilling to concede it initially, as even wikipedia recognises, without essentially total German control over the state - and after 1917 and into earlyh 1918 they ditched the idea of an Austrian monarch as well. After all, the Oath crisis showed that the Poles cared little about who their King was - they just wanted total independence, which Germany would not offer them. Thus, what advantage does Germany have by appointing a politically dubious monarch?

So, if you're going to call my timeline implausible, at least look at wikipedia first. Otherwise, unlike what the chap discussing Hungary mentioned when he proposed plenty of helpful information in a non-critical manner, don't intentionally try and cast aspersions on my timeline in a way that you have done before, specifically criticizing the plausibility of my work based on hundreds of hours of research - based on your own lack of it.

Otherwise, just dont read it - plausibility evidently isn't what you're looking for.

“The Germans are literal Huns who will rape everyone you know and love if you don’t kill them first” is definitely a step above “Kraut and Jerry,” I agreeIt's got about £7 billion in additional national debt, though... And much of it was owed to the Americans. (Geddes and Baldwin are going to have so much more fun negotiating that in *this* timeline!) We might be able to shave off a little of that, since British combat operations on the Western Front end by July, rather than November, but since full mobilization was maintained...probably not *too* much.

Worse, it won't be getting any reparations from Germany this time, and because it will be forced to maintain the Navy (and, uh, a nascent air force) on a larger scale, there won't be near as much of a "peace dividend."

But probably the greatest pain will be the horrific casualties they sustained, and sharper questions about whether it was worth it. Your school chums are all dead, the zeppelins blew up your uncle's flat in Rotherhithe, and yet the Hun is now running Europe. The fact that His Majesty is now sovereign of a bunch of New Guinea headhunters and unhappy Marsh Arabs probably won't feel like much consolation. No one can pretend that this was a war to end all wars, and the way this war was sold* - and bought into - on the British homefront is, I suspect, going to make it feel like a real failure, no matter how deft Whitehall's diplomats were in Copenhagen.

View attachment 797258View attachment 797259View attachment 797260View attachment 797261

____

Cécile Vallée has made an compelling case that British anti-German propaganda in WW1 was a good deal more vicious and ill-humored than its WW2 propaganda, which sounds unlikely and counterintuitive to us today; but the weight of the evidence suggests that it's true to a large degree.

Another thing with the french colonies, since France lost the iron deposits of Briey to Germany they might feel inclined to spend more time looking for resources in Africa. Also Bugatti stays a german company now huh, I wonder how this affects its development.

Gabon and Congo have some fair deposits....uh. Whoops.

But yes, perhaps it's time to start doing some serious mineral surveys in French West Africa.

When your cause is actually decent, you don't have to exaggerate and lie so much.Cécile Vallée has made an compelling case that British anti-German propaganda in WW1 was a good deal more vicious and ill-humored than its WW2 propaganda, which sounds unlikely and counterintuitive to us today; but the weight of the evidence suggests that it's true to a large degree.

Germany got Gabon IIRC, which is a source of oil so another reason for them to not give up on their navy.Gabon and Congo have some fair deposits....uh. Whoops.

But yes, perhaps it's time to start doing some serious mineral surveys in French West Africa.

When your cause is actually decent, you don't have to exaggerate and lie so much.

Sure, that's a possibility. (Though while I think of the Great War as a mistake, I might not go quite so far as to call it an indecent cause.)

But Vallée actually proposes her own theory on why there was such a shift in WW2 propaganda:

The leitmotiv of WW2 British posters is derision and belittling of the enemy, who is more often than not Hitler. Interestingly, although some of the themes in British posters are serious in tone, very few picture the enemy as actually frightening. The ‘beastly Hun’ of WW1 seems to have almost disappeared from British-produced posters. One possible reason for this may be the realisation in government quarters that the gross exaggerations of WW1 propaganda had led to a certain disbelief in the British population. It is indeed generally agreed that because of the popularity and virulence of atrocity propaganda, the poison of hatred remained. Not only did it give propaganda a bad name, but it inadvertently helped Hitler in his own home propaganda and, more importantly still, it made the real atrocities of the 30s and 40s more difficult to believe. One may therefore see in this toning down an attempt not to fall into the same trap of exaggeration.

And perhaps I am tempted to tack on something to the observation I made in my post at the end: "No one can pretend that this was a war to end all wars, and the way this war was sold* - and bought into - on the British homefront is, I suspect, going to make it feel like a real failure, no matter how deft Whitehall's diplomats were in Copenhagen." To wit: There may be an even greater danger - which I am not prepared to evaluate or quantify yet - that a large cohort of the British populace might begin to wonder whether the the war they bought wasn't actually the war they were sold.

Last edited:

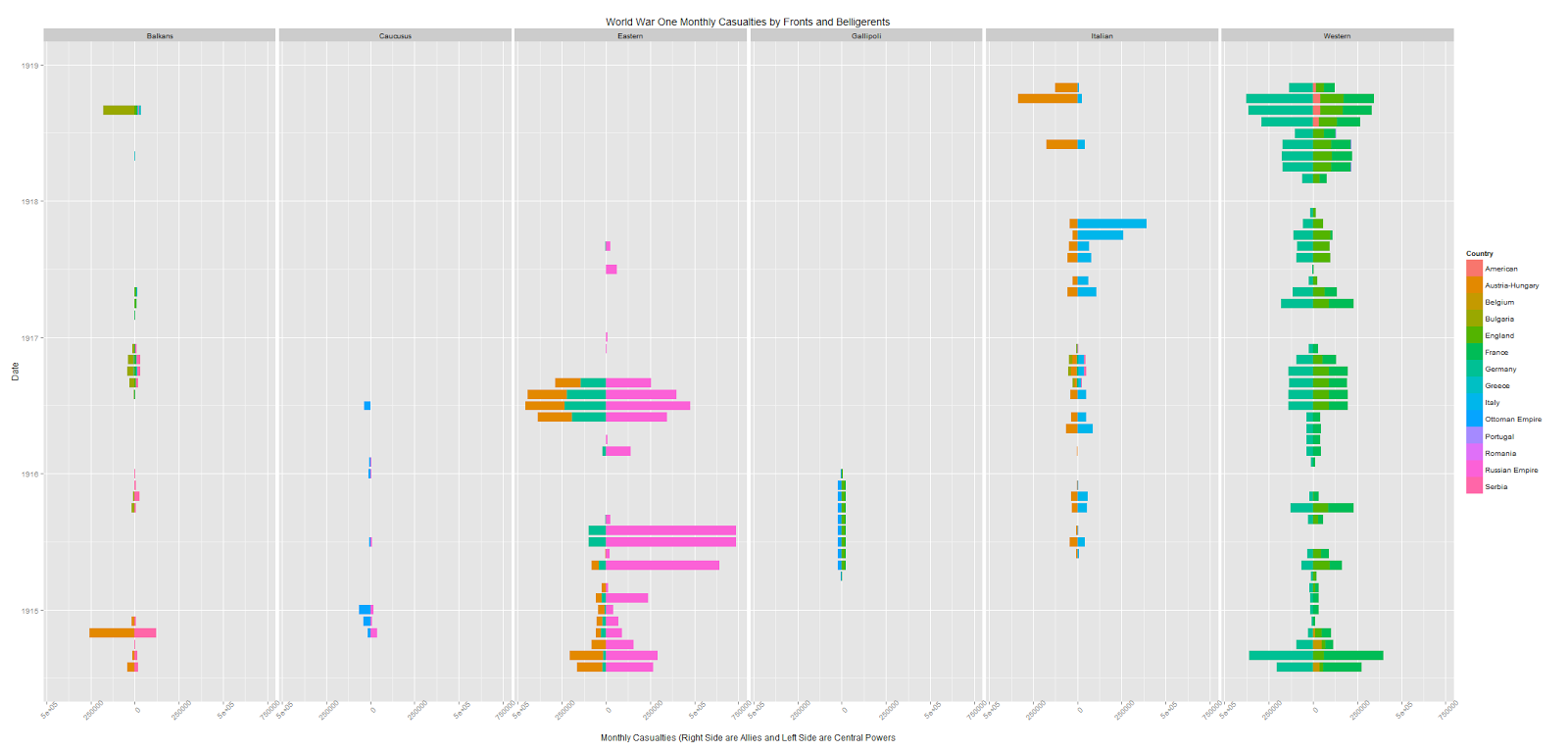

One other thought I have had is one which relates to the casualties question which we have discussed so much here: Namely, how its legacy plays out politically, culturally, economically in each country in a Great War which had a quite different end than the one we know historically.

This may or may not have much value to our author, but I did once come across a helpful graph which outlines, in broad strokes, just who was sustaining how many casualties in each month of the war, and in which theater. This won't mitigate the total carnage THAT much, but you can see that the termination of combat operations in Western Europe by the beginning of July DOES avert some pretty sizable casualty returns for Germany, France, and Britain (and, uh, America). But note, too, the massive hit the Austro-Hungarians took in [EDIT: September and October 1918] in OTL: that won't be quite the case here. Hey, the Austrians need all the good news they can get.

I'm trying to see if I can get hold of the actual data on which this graph is based, and I'll post it if I can get it.

This may or may not have much value to our author, but I did once come across a helpful graph which outlines, in broad strokes, just who was sustaining how many casualties in each month of the war, and in which theater. This won't mitigate the total carnage THAT much, but you can see that the termination of combat operations in Western Europe by the beginning of July DOES avert some pretty sizable casualty returns for Germany, France, and Britain (and, uh, America). But note, too, the massive hit the Austro-Hungarians took in [EDIT: September and October 1918] in OTL: that won't be quite the case here. Hey, the Austrians need all the good news they can get.

I'm trying to see if I can get hold of the actual data on which this graph is based, and I'll post it if I can get it.

Last edited:

Threadmarks

View all 45 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Map of Europe as of the signing of the Treaty of Zurich Social Conflict & Elections: France (August 1918 - May 1919) The Italian Civil War (December 1918 - January 1919) Social Conflict & Elections: The United States (October 1918 - January 1920) The Habsburg Reckoning I (September 1918 - February 1919) The Russian Civil War | The Whites Advance…? (October 1918 - March 1919) The New Ummah | The Second Arab Conquest (October 1918 - December 1919) The New Ummah | Ottoman Woes (November 1918 - June 1919)

Share: