Up next, the CSA will face its first major challenge to survive as a country: The Panic of 1873.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Sun Never Rises: If The Confederacy Won

- Thread starter PGSBHurricane

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 16 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Part 3: The Treaty of Richmond Part 4: The Aftermath of the Union Part 5: The Start of Confederate Expansion Part 6: The Cuba Question Part 12: The Rise of the Entente and the Deconstruction of the Confederacy Part 13: The Hapsburgs and The Beginning of The End Part 14: The Beginning of The Great War Part 15: Culture of the Early Twentieth Century

Part 7: The Panic of 1873

Part 7: The Panic of 1873

Following the War for Southern Secession, there was a railroad construction boom across the North American continent, with 33,000 miles of new tracks being built between 1868 and 1873. Much of this boom was driven by government land grants and subsidies, especially in the Union. In the Confederacy, it was more so to show that it was industrializing to its European allies: Britain and France. It was no coincidence that the city of Birmingham, Alabama was becoming increasingly known for its steel production, albeit on a small scale compared to its northern counterparts. The railroad industry soon overtook agriculture as the United States’ largest industry and it became the third-largest industry in the Confederate States. Of course, this involved large amounts of money and risk. This large infusion of cash from speculators on the stock market caused abnormally high growth in the railroad industry and the overbuilding of docks and factories.

Coincidingly, the Black Friday Panic of 1869, the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, and the equine flu epidemic of 1872 worked together to slow down the economy. But the biggest setback developed in 1871 when the German empire discontinued minting Silver Thaler coins upon unification, causing reduced demand for silver and downward pressure on the value of silver. In turn, the United States Congress passed the Coinage Act of 1873, which moved the USA to a de facto gold standard, meaning that silver would no longer be bought at a statutory price or be converted into silver coins. The domestic supply of money was further reduced. Interest rates went up and hurt farmers and others who carried high levels of debt. People began shying away from long-term investments, including in railroads. In September 1873, the US economy was entering crisis mode. Multiple bank failures occurred and temporary closure of the New York stock market took place for 10 days starting September 20. Factories laid-off workers and unemployment rose dramatically. The effects were felt everywhere from New York to Chicago to San Francisco. By November 1873, 55 of the nation's railroads had failed, and 60 more went bankrupt within another 10 months. Construction of new rail lines plummeted from 7,500 miles of track per year in 1872 to just 1,600 miles per year in 1875. The industry would never completely recover.

Its southern neighbor was not faring any better. While it was not quite as hurt by the popping of the railroad bubble as the North, it did not go unnoticed either. The New Orleans Stock Exchange, just like in New York, was shut down for 10 days beginning September 20, 1873. Unemployment reached its highest levels in Confederate territory since 1837 (more than two decades before the CSA even existed). Railroad construction per year was barely less than 500 miles by 1875. To make things worse for them, Great Britain, its primary trading partner, was suffering from the Panic arguably worse than anyone else in the world. On an international scale, the 1869 opening of the Suez Canal was a cause of the Panic of 1873. This was because goods from the Far East (especially the British Raj in India) had previously sailed around the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa to get to Britain. Sailing vessels were not adaptable for use through the Suez Canal and new ships had to be built, this British trade suffered until 1897. This period was known as the Long Depression in Britain because of high levels of bankruptcies, unemployment, and halting public works in addition to the trade slump. Even France was suffering similarly (although not quite as badly).

All of this meant that southern cotton was less viable to the European (and even the USA) market. Cotton prices fell domestically and shipments across the world plummeted. With the depression, ambitious railroad building programs crashed across the CSA, South, leaving most states deep in debt and burdened with heavy taxes. Between this and the reduced viability of slavery, a common response to this was retrenchment, with spending at record lows. In the Upper States of Kentucky, Missouri, and Virginia, where cotton was not as prosperous to start with and slaves were seen as luxury items, there were even debates about emancipating slaves entirely. Also in those states, cuts in wages and bad working conditions led to a Great Railroad Strike in 1877 beginning in Martinsburg, Virginia. However, this was brutally put down by government troops and was characterized in the press as an insurrection rather than an act of desperation. Similar strikes happened to its northern neighbor. By 1878, the damage the Panic had caused was done and would shape the country and its institutions (including slavery) for decades to come. By 1880, five states - Arizona, Coahuila, New Chichuaha, New Sonora, and South California - had abolished slavery entirely and two more (Kentucky and Missouri) plus Indian Territory had just passed gradual emancipation acts. These states stood alone with their futures in the air. Would they be the new leaders of an industrialized tomorrow or would they be shunned by the rest of the agrarian Confederacy?

Following the War for Southern Secession, there was a railroad construction boom across the North American continent, with 33,000 miles of new tracks being built between 1868 and 1873. Much of this boom was driven by government land grants and subsidies, especially in the Union. In the Confederacy, it was more so to show that it was industrializing to its European allies: Britain and France. It was no coincidence that the city of Birmingham, Alabama was becoming increasingly known for its steel production, albeit on a small scale compared to its northern counterparts. The railroad industry soon overtook agriculture as the United States’ largest industry and it became the third-largest industry in the Confederate States. Of course, this involved large amounts of money and risk. This large infusion of cash from speculators on the stock market caused abnormally high growth in the railroad industry and the overbuilding of docks and factories.

Coincidingly, the Black Friday Panic of 1869, the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, and the equine flu epidemic of 1872 worked together to slow down the economy. But the biggest setback developed in 1871 when the German empire discontinued minting Silver Thaler coins upon unification, causing reduced demand for silver and downward pressure on the value of silver. In turn, the United States Congress passed the Coinage Act of 1873, which moved the USA to a de facto gold standard, meaning that silver would no longer be bought at a statutory price or be converted into silver coins. The domestic supply of money was further reduced. Interest rates went up and hurt farmers and others who carried high levels of debt. People began shying away from long-term investments, including in railroads. In September 1873, the US economy was entering crisis mode. Multiple bank failures occurred and temporary closure of the New York stock market took place for 10 days starting September 20. Factories laid-off workers and unemployment rose dramatically. The effects were felt everywhere from New York to Chicago to San Francisco. By November 1873, 55 of the nation's railroads had failed, and 60 more went bankrupt within another 10 months. Construction of new rail lines plummeted from 7,500 miles of track per year in 1872 to just 1,600 miles per year in 1875. The industry would never completely recover.

Its southern neighbor was not faring any better. While it was not quite as hurt by the popping of the railroad bubble as the North, it did not go unnoticed either. The New Orleans Stock Exchange, just like in New York, was shut down for 10 days beginning September 20, 1873. Unemployment reached its highest levels in Confederate territory since 1837 (more than two decades before the CSA even existed). Railroad construction per year was barely less than 500 miles by 1875. To make things worse for them, Great Britain, its primary trading partner, was suffering from the Panic arguably worse than anyone else in the world. On an international scale, the 1869 opening of the Suez Canal was a cause of the Panic of 1873. This was because goods from the Far East (especially the British Raj in India) had previously sailed around the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa to get to Britain. Sailing vessels were not adaptable for use through the Suez Canal and new ships had to be built, this British trade suffered until 1897. This period was known as the Long Depression in Britain because of high levels of bankruptcies, unemployment, and halting public works in addition to the trade slump. Even France was suffering similarly (although not quite as badly).

All of this meant that southern cotton was less viable to the European (and even the USA) market. Cotton prices fell domestically and shipments across the world plummeted. With the depression, ambitious railroad building programs crashed across the CSA, South, leaving most states deep in debt and burdened with heavy taxes. Between this and the reduced viability of slavery, a common response to this was retrenchment, with spending at record lows. In the Upper States of Kentucky, Missouri, and Virginia, where cotton was not as prosperous to start with and slaves were seen as luxury items, there were even debates about emancipating slaves entirely. Also in those states, cuts in wages and bad working conditions led to a Great Railroad Strike in 1877 beginning in Martinsburg, Virginia. However, this was brutally put down by government troops and was characterized in the press as an insurrection rather than an act of desperation. Similar strikes happened to its northern neighbor. By 1878, the damage the Panic had caused was done and would shape the country and its institutions (including slavery) for decades to come. By 1880, five states - Arizona, Coahuila, New Chichuaha, New Sonora, and South California - had abolished slavery entirely and two more (Kentucky and Missouri) plus Indian Territory had just passed gradual emancipation acts. These states stood alone with their futures in the air. Would they be the new leaders of an industrialized tomorrow or would they be shunned by the rest of the agrarian Confederacy?

Last edited:

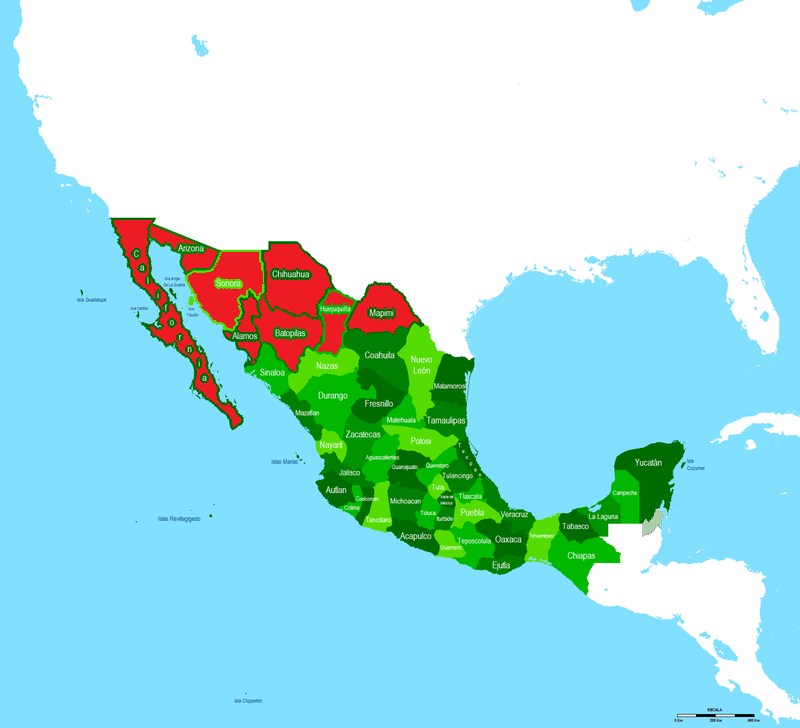

Map of Confederate Mexico

By the way, here are the Mexican territories previously annexed by the Confederacy in earlier chapters. Those territories are in red.

Part 8: The End of Confederate Slavery

Part 8: The end of Confederate Slavery

In 1880, Seven states and an additional territory were in the process of abolishing slavery when no one else looked like they were going to. Rumors about seceding from the CSA swirled through the 1880s. Meanwhile, the CSA was torn between its two alliances: one with Britain and the other with Brazil, who represented the opposite ends of the abolition spectrum. Further complicating the crisis was the pledge to abolish slavery by January 1, 1898. Nevertheless, the Confederacy and Brazil became each other's top trading partners in the Americas. Despite only abolishing the Atlantic Slave Trade in 1850, Brazil seemed to be abolishing slavery faster than the Confederacy, in part due to international pressure. In 1871, the passage “Law of the Free Womb” declared all children of slaves born after the law was passed as free, and the 1885 Sexagenarian Law freed slaves over 60 years of age. At the same time, relatively few slaves had been emancipated in the Confederacy. Those emancipated from former Mexican territories were small in number, most Indians in Indian Territory didn’t own slaves, and the Upper South (especially Kentucky and Missouri) had smaller slave populations compared to other Confederate states. Additionally, it was starting to feel the pressure to abolish slavery from the British and other European powers. Fewer countries were willing to do business with the CSA. In spite of British assistance, its debts were mounting and the risk of default was also increasing.

Puerto Rico abolished slavery in 1885 in response to the Brazilian Sexagernarain Law, and Cuba in 1886. It wasn’t until after Brazilian emancipation in 1888 did the original eleven Confederate states do anything. The first two to act were North Carolina and Virginia. In the former, it passed the Slave Codes in 1872, meant to further tighten owners’ grasp on their slaves. The Panic of 1873 and large numbers of escaped slaves in the 1880s showed how ineffective the codes actually were. In Virginia, not only were there a high number of escaped slaves but brutality against slaves was stronger than ever and was responsible for many slave deaths. This served as a wake-up call for a large number of Virginian whites about the horrors of slavery, with even president Stonewall Jackson (elected in 1880), as a native Virginian, addressing this. In both states, industrialization was underway and there was second-hand embarrassment about Brazil modernizing faster than the Confederacy. In 1888 and 1889 respectively (100 years after each became states), Virginia and North Carolina did what was thought as impossible: emancipated all their slaves. The public reaction was mixed. Some thought it was a step towards modernization with the abandonment of an archaic practice. Others feared this would create competition for jobs between poor whites and freed slaves. Yet others, although not as many as in the first two groups, were outraged because they saw nonwhites as worth nothing except slavery for whites.

As Indian Territory was renamed Oklahoma and opened to white settlement in 1889, a condition was the prohibition of importing slaves. In neighboring Arkansas, the economy deteriorated to the point that it was one of the poorest states in the Confederacy by 1893. The Panic of 1893 only made things worse for the agriculture-dependent state. Slaves were becoming expensive to maintain, let alone purchase. It didn’t help that next-door Missouri was greatly benefiting from industrialization thanks to Kansas City and especially St. Louis. With attitudes towards slavery gradually changing, the Arkansas state legislature passed a gradual emancipation act that would liberate all Arkansas slaves by 1913, 20 years after passage. Texas passed a similar act in 1895, allowing 15 years for emancipation, but the reasons were entirely different. Texas was far more economically prosperous than Arkansas, but in no small part from diversification. The city of Galveston was known as the Wall Street of the Confederacy due to its port location and strong financial market. The 1894 discovery of oil in Corsicana was the start of a major oil boom that would last for fifty years and be one of the most profitable industries in Texan history, more so than slavery. Manufacturing was also starting to take hold in Texas, particularly around Dallas. Abolishing slavery was inevitable.

It was ultimately Tennessee that put that nail in the coffin. That can be traced back to 1875 with the passage of the Zebra Law, which put slaves in chains and sent them to jail for crimes as minor as stealing a one-cent fence rail. Treatment of slaves got so bad in some areas of the state (i.e. using them in coal mines) that widespread slave revolts took place in 1892, prompting a debate about slavery. The importation of slaves into Tennessee from other states was banned in 1893 plus additional measures such as sexagenarian and free womb laws. Public pressure to improve conditions that slaves toiled in resulted in the abolition of slavery in Tennessee in 1896. By now, fifteen states and territories were in the process of abolishing slavery or had abolished it, one more than required to ratify the Gold Amendment which abolished slavery nationwide in 1896, effective on January 1, 1897 despite resistance from the other six states. This did not mean that slavery would end overnight but rather that interstate slave trading was banned and all newborn blacks were not enslaved. Once again, the Confederacy’s future remained divided and uncertain.

In 1880, Seven states and an additional territory were in the process of abolishing slavery when no one else looked like they were going to. Rumors about seceding from the CSA swirled through the 1880s. Meanwhile, the CSA was torn between its two alliances: one with Britain and the other with Brazil, who represented the opposite ends of the abolition spectrum. Further complicating the crisis was the pledge to abolish slavery by January 1, 1898. Nevertheless, the Confederacy and Brazil became each other's top trading partners in the Americas. Despite only abolishing the Atlantic Slave Trade in 1850, Brazil seemed to be abolishing slavery faster than the Confederacy, in part due to international pressure. In 1871, the passage “Law of the Free Womb” declared all children of slaves born after the law was passed as free, and the 1885 Sexagenarian Law freed slaves over 60 years of age. At the same time, relatively few slaves had been emancipated in the Confederacy. Those emancipated from former Mexican territories were small in number, most Indians in Indian Territory didn’t own slaves, and the Upper South (especially Kentucky and Missouri) had smaller slave populations compared to other Confederate states. Additionally, it was starting to feel the pressure to abolish slavery from the British and other European powers. Fewer countries were willing to do business with the CSA. In spite of British assistance, its debts were mounting and the risk of default was also increasing.

Puerto Rico abolished slavery in 1885 in response to the Brazilian Sexagernarain Law, and Cuba in 1886. It wasn’t until after Brazilian emancipation in 1888 did the original eleven Confederate states do anything. The first two to act were North Carolina and Virginia. In the former, it passed the Slave Codes in 1872, meant to further tighten owners’ grasp on their slaves. The Panic of 1873 and large numbers of escaped slaves in the 1880s showed how ineffective the codes actually were. In Virginia, not only were there a high number of escaped slaves but brutality against slaves was stronger than ever and was responsible for many slave deaths. This served as a wake-up call for a large number of Virginian whites about the horrors of slavery, with even president Stonewall Jackson (elected in 1880), as a native Virginian, addressing this. In both states, industrialization was underway and there was second-hand embarrassment about Brazil modernizing faster than the Confederacy. In 1888 and 1889 respectively (100 years after each became states), Virginia and North Carolina did what was thought as impossible: emancipated all their slaves. The public reaction was mixed. Some thought it was a step towards modernization with the abandonment of an archaic practice. Others feared this would create competition for jobs between poor whites and freed slaves. Yet others, although not as many as in the first two groups, were outraged because they saw nonwhites as worth nothing except slavery for whites.

As Indian Territory was renamed Oklahoma and opened to white settlement in 1889, a condition was the prohibition of importing slaves. In neighboring Arkansas, the economy deteriorated to the point that it was one of the poorest states in the Confederacy by 1893. The Panic of 1893 only made things worse for the agriculture-dependent state. Slaves were becoming expensive to maintain, let alone purchase. It didn’t help that next-door Missouri was greatly benefiting from industrialization thanks to Kansas City and especially St. Louis. With attitudes towards slavery gradually changing, the Arkansas state legislature passed a gradual emancipation act that would liberate all Arkansas slaves by 1913, 20 years after passage. Texas passed a similar act in 1895, allowing 15 years for emancipation, but the reasons were entirely different. Texas was far more economically prosperous than Arkansas, but in no small part from diversification. The city of Galveston was known as the Wall Street of the Confederacy due to its port location and strong financial market. The 1894 discovery of oil in Corsicana was the start of a major oil boom that would last for fifty years and be one of the most profitable industries in Texan history, more so than slavery. Manufacturing was also starting to take hold in Texas, particularly around Dallas. Abolishing slavery was inevitable.

It was ultimately Tennessee that put that nail in the coffin. That can be traced back to 1875 with the passage of the Zebra Law, which put slaves in chains and sent them to jail for crimes as minor as stealing a one-cent fence rail. Treatment of slaves got so bad in some areas of the state (i.e. using them in coal mines) that widespread slave revolts took place in 1892, prompting a debate about slavery. The importation of slaves into Tennessee from other states was banned in 1893 plus additional measures such as sexagenarian and free womb laws. Public pressure to improve conditions that slaves toiled in resulted in the abolition of slavery in Tennessee in 1896. By now, fifteen states and territories were in the process of abolishing slavery or had abolished it, one more than required to ratify the Gold Amendment which abolished slavery nationwide in 1896, effective on January 1, 1897 despite resistance from the other six states. This did not mean that slavery would end overnight but rather that interstate slave trading was banned and all newborn blacks were not enslaved. Once again, the Confederacy’s future remained divided and uncertain.

Do I see a confederate Civil War coming up?By the way, here are the Mexican territories previously annexed by the Confederacy in earlier chapters. Those territories are in red.View attachment 510981

Currently it’s not in the cards but that could change.Do I see a confederate Civil War coming up?

Sorry for not replying sooner but Davis wanted DC as the Confederate capital outright. The free city thing was just a compromise.They were yes, but the scenario you put up that leads to them recognizing the Confederacy is ASB. There's no way the Confederates could have ever put Washington under siege, it's just not possible. You should recognize the fact that both Confederate invasions of the North were failures, and center your timeline on Lee successfully using attrition and annihilation to break the minds of the Union government and cause them to just let the South go. It's the only way they could have won, and if the Confederacy does it well, which I honestly think it could have, Britain and France would recognize it, and perhaps even pull a Navarino on the Union fleet to break the blockade of the Confederacy and reopen the Trans-Atlantic cotton trade, but I cannot see them go any further as I would certainly expect Lincoln to request an armistice in the aftermath of such a disaster.

Anyway, even if the Confederates win their independence, I would still expect the Confederate government not to want to annex Maryland; the Potomac would be a very advantageous river border for them to have, and I would expect Davis to push for the US-CS border to be along the Potomac, Ohio and Missouri Rivers; he would want to be able to keep Yankee troops on the other side of the rivers to prevent them from advancing into his territory much easier in a potential second war. Of course, Davis may still want Maryland as a Confederate state anyway, which would make my point here moot.

About Missouri, the Missouri River Basin voted primarily for the Unionist John Bell in the 1860 election, which clearly indicates their preference against secession. On the other hand, many counties in the Southernmost third of Missouri voted for Breckinridge, the Southern Democrat candidate. These regions would be the nucleus of the new Missouri I propose.

Also, why does Jeff Davis so adamantly demand that DC becomes a free city? This would seem to be a very contentious debate that would satisfy neither side. If I were the Confederate President during negotiations over a treaty to end the Civil War, I would forgo the free city proposal, and instead demand massive economic reparations from the North in order to fund Davis' planned economic reconstruction (yeah, I know) of the South, as its economy would be absolutely devasted from having to hold up the weight the war would bring bearing down on it. This A) brings money into Southern coffers after the war and B) removes the need to get loans from European countries that the South would have to pay back later; in this scenario, the South would not need to pay the Union back, as they won the money fair and square.

Part 9: Politics And Economics in the North American Gilded Age

Part 9: Politics And Economics in the North American Gilded Age

The three final decades of the nineteenth century, collectively known as the Gilded Age in the Americas, was a very turbulent time in the Union and Confederacy alike. The Democrats held onto the presidency for every term until 1888 with the election of the New Republican Party (formerly Whig Party) candidate Benjamin Harrison. Many in this time period were describing the USA as a one-party regime. In many ways, they were correct. Aside from the presidency, it was impossible for New Republicans to gain a majority on either the Supreme Court or in Congress and even being elected was difficult. Outside of New England, almost all the governorships were held by Democrats. This political period would last until the Panic of 1893, which was in many ways worse than the Panic of 1873. Unlike the latter which was felt worldwide, most of the former’s impact were restricted to the United States and, to a lesser extent, the Confederate States. After the Panic of 1873 and into the 1880s, the United States had experienced rapid economic growth and expansion that depended on high international commodity prices. This was exposed when wheat prices crashed in 1893. On February 20 of that year, things got worse with the appointment of receivers for the greatly overextended Philadelphia and Reading Railroad.

When Cleveland took office, he convinced Congress to repeal the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, which he felt was mainly responsible for the economic crisis, in order to prevent the depletion of the government's gold reserves. Nevertheless, silver prices continued to drop to as low as $0.60 in December 1894. People rushed in record numbers during this time to withdraw their money from the banks, causing widespread bank runs. Meanwhile, gold reserves in the U.S. Treasury fell to dangerously low levels, forcing President Cleveland to borrow $65 million in gold from Wall Street banker J.P. Morgan and the Rothschilds of England. Cleveland was blamed for this mess as he was effectively the head of the Democratic party. The Democrats became seen as keeping the United States behind the rest of the world. This caused a big shift in the political arena. The People's Party, an agrarian-populist political party in the United States, was founded in 1891. In the 1890s it was a major left-wing force in American politics. Especially popular in the West, it was highly critical of banks and railroads and allied itself with the labor movement. It peaked in popularity in 1892 when its ticket won five states in the presidential election (Colorado, Idaho, Kansas, Nevada, and North Dakota), and won nine seats in the House in the 1894 midterm elections. The populists eventually merged with the New Republican, leading to a landslide victory for William McKinley in 1896. His main success, though, was in foreign policy. With a naval base established at Pearl Harbor in 1887 and US sugar interests, encouraging the overthrow of the monarchy in 1893, McKinley annexed Hawaii in 1898 before becoming an official US territory in 1900. In 1899, the US negotiated for the purchase of Guam, the Midway Islands, Samoa, and Wake Island with the British and Germans. The Caribbean would not be a prime area of focus until the 20th century.

Meanwhile, the Confederacy also somewhat suffered from the Panic of 1893. Most of this was manifested when US purchases of cotton took a nosedive. After the Panic of 1873, the Confederate government negotiated cotton quotas with USA business leaders to aid each other with industrialization despite opposition from the latter’s government. Without the purchase of cotton from the Union, the still-largely-agricultural-dependent CSA lost money quickly. Not helping things was that when the New York Stock Exchange crashed, Confederate citizens were panicking that it would ripple beyond US borders and thus many in Galveston and New Orleans were withdrawing their investments from the stock market. This effectively became a self-fulfilling prophecy. Like in the USA West, farmers in the Confederate Deep were pushing for greater checks on a capitalist system that was hurt the working-class whites and provided little to no labor protections. By 1897, the two major parties - the pro-industrial Constitution Party and the pro-Old South (now minus slavery) Dixiecrats were challenged by the populist Liberty Party especially in Alabama, North Carolina, and Texas. Nevertheless, the Liberty Party failed to win the presidency but made third parties much more viable in future elections.

Note: The next part will focus on society in the USA and CSA up to 1900.

The three final decades of the nineteenth century, collectively known as the Gilded Age in the Americas, was a very turbulent time in the Union and Confederacy alike. The Democrats held onto the presidency for every term until 1888 with the election of the New Republican Party (formerly Whig Party) candidate Benjamin Harrison. Many in this time period were describing the USA as a one-party regime. In many ways, they were correct. Aside from the presidency, it was impossible for New Republicans to gain a majority on either the Supreme Court or in Congress and even being elected was difficult. Outside of New England, almost all the governorships were held by Democrats. This political period would last until the Panic of 1893, which was in many ways worse than the Panic of 1873. Unlike the latter which was felt worldwide, most of the former’s impact were restricted to the United States and, to a lesser extent, the Confederate States. After the Panic of 1873 and into the 1880s, the United States had experienced rapid economic growth and expansion that depended on high international commodity prices. This was exposed when wheat prices crashed in 1893. On February 20 of that year, things got worse with the appointment of receivers for the greatly overextended Philadelphia and Reading Railroad.

When Cleveland took office, he convinced Congress to repeal the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, which he felt was mainly responsible for the economic crisis, in order to prevent the depletion of the government's gold reserves. Nevertheless, silver prices continued to drop to as low as $0.60 in December 1894. People rushed in record numbers during this time to withdraw their money from the banks, causing widespread bank runs. Meanwhile, gold reserves in the U.S. Treasury fell to dangerously low levels, forcing President Cleveland to borrow $65 million in gold from Wall Street banker J.P. Morgan and the Rothschilds of England. Cleveland was blamed for this mess as he was effectively the head of the Democratic party. The Democrats became seen as keeping the United States behind the rest of the world. This caused a big shift in the political arena. The People's Party, an agrarian-populist political party in the United States, was founded in 1891. In the 1890s it was a major left-wing force in American politics. Especially popular in the West, it was highly critical of banks and railroads and allied itself with the labor movement. It peaked in popularity in 1892 when its ticket won five states in the presidential election (Colorado, Idaho, Kansas, Nevada, and North Dakota), and won nine seats in the House in the 1894 midterm elections. The populists eventually merged with the New Republican, leading to a landslide victory for William McKinley in 1896. His main success, though, was in foreign policy. With a naval base established at Pearl Harbor in 1887 and US sugar interests, encouraging the overthrow of the monarchy in 1893, McKinley annexed Hawaii in 1898 before becoming an official US territory in 1900. In 1899, the US negotiated for the purchase of Guam, the Midway Islands, Samoa, and Wake Island with the British and Germans. The Caribbean would not be a prime area of focus until the 20th century.

Meanwhile, the Confederacy also somewhat suffered from the Panic of 1893. Most of this was manifested when US purchases of cotton took a nosedive. After the Panic of 1873, the Confederate government negotiated cotton quotas with USA business leaders to aid each other with industrialization despite opposition from the latter’s government. Without the purchase of cotton from the Union, the still-largely-agricultural-dependent CSA lost money quickly. Not helping things was that when the New York Stock Exchange crashed, Confederate citizens were panicking that it would ripple beyond US borders and thus many in Galveston and New Orleans were withdrawing their investments from the stock market. This effectively became a self-fulfilling prophecy. Like in the USA West, farmers in the Confederate Deep were pushing for greater checks on a capitalist system that was hurt the working-class whites and provided little to no labor protections. By 1897, the two major parties - the pro-industrial Constitution Party and the pro-Old South (now minus slavery) Dixiecrats were challenged by the populist Liberty Party especially in Alabama, North Carolina, and Texas. Nevertheless, the Liberty Party failed to win the presidency but made third parties much more viable in future elections.

Note: The next part will focus on society in the USA and CSA up to 1900.

Last edited:

I like the Populist merging with the Republicans to capture the white house. However, populists in 1896 were certainly against William McKinley. I'm assuming that the coalition/merge party ran a balanced ticket with a prominent populist as the vp. So, I'm guessing Weaver or Bryan himself was McKinley' s running mate.

In his first term, I’ll assume that Bryan was the Vice President. As the populist movement was dying by 1900 (although it won’t be dead as soon as it was in OTL), I have him taking Teddy Roosevelt as his pick.I like the Populist merging with the Republicans to capture the white house. However, populists in 1896 were certainly against William McKinley. I'm assuming that the coalition/merge party ran a balanced ticket with a prominent populist as the vp. So, I'm guessing Weaver or Bryan himself was McKinley' s running mate.

That makes sense, seeing that by the time the 1900 election rolls around, Bryan and McKinley will have serious disagreements over policy. Maybe Bryan fights Mckinly for the nomination even.In his first term, I’ll assume that Bryan was the Vice President. As the populist movement was dying by 1900 (although it won’t be dead as soon as it was in OTL), I have him taking Teddy Roosevelt as his pick.

I have the Populists and New Republicans merge since at the time the OTL Republican Party was generally more liberal than Democrats and the Populists themselves were left-winged. Meanwhile, it’s been over 30 years since the war ended meaning that the idea of the Democrats being the “good” party is wearing off, especially with the Panic 1893 making them look bad.That makes sense, seeing that by the time the 1900 election rolls around, Bryan and McKinley will have serious disagreements over policy. Maybe Bryan fights Mckinly for the nomination even.

Last edited:

Part 10: North American Society During the Gilded Age and Turn of the Century

Part 10: North American Society During the Gilded Age and Turn of the Century

Immigration to the United States from 1880 all the way to the breakout of the Great War in 1914 occurred in almost unprecedented numbers. From southern Europe came 4 million Italians. This was fueled by Southern Italy, including Sicily and Sardinia, where peasants suffered from severe hardship (bad soil, illiteracy, disease, malnutrition, exploitation, and violence). Initially, the number of Italians going to the USA and CSA was in line with each other’s population. But the lynching of 11 Italians in New Orleans 1891 largely ended Italian immigration to the CSA, with the vast majority (80-85%) entering the North American continent via Ellis Island in New York Harbor. They were greeted by the Statue of National Pride, as gifted by the German Empire in 1886. Most settled in urban centers such as New York where they arrived. In contrast, a much higher proportion of Jews (40-45%), went South due to Union alignment with Russia. Beginning in 1881, after the assassination of Alexander II, the Russian government placed harsh restrictions on the rights and mobility of Jews in its territory, restricting them to the Pale of Settlement. Anti-Semitic violence known as “pogroms” sanctioned by the czar drove two million Jews out of the Russian Empire and into North America. Approximately 60% entered via New York while 40% entered in Charleston Harbor in South Carolina, greeted by the Statue of Liberty (which was gifted by France). For Jews heading to the Union, New York City was the top destination and they often learned German alongside or before learning English. For those heading to the Confederacy, cosmopolitan centers such as Charleston (historically one of the largest Jewish communities in the Americas), Galveston (courtesy of the Galveston movement from 1907 to 1914), New Orleans, and South Florida, along with industrial centers in St. Louis and Richmond.

To a lesser extent, but nevertheless a highly visible one, German and Irish immigrants provided roughly one million immigrants apiece in this time period. Almost all of these groups went to the Union as the German Empire and the USA had close ties to each other - to the point where German was the second most commonly spoken language after English - and the Irish were seeking to get away from their British oppressors, who largely influenced the CSA. Immigrants from elsewhere in southern and Eastern Europe were proportionally split between the CSA and USA as their destinations, although those who intended to stay temporarily leaned more towards the Union due to perceived greater economic opportunity. While actively excluded from the Union under the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the CSA government was relatively welcoming towards Chinese, whom they sought after for labor in the Mississippi Delta region. Despite frequent casual racism from Confederate whites, most Chinese laborers (which only numbered a few thousand) ultimately stayed in the country.

By 1890, the majority of states and territories in the Union had passed compulsory education attendance laws, with the last four states being New Mexico (1891), Pennsylvania (1895), Indiana (1897), West Virginia (1897), Maryland (1902), and Delaware (1907). In contrast, only Cuba (1895), Kentucky (1896), Arizona (1899), and Puerto Rico (1899) had enacted compulsory school attendance laws before 1900. Missouri and Tennessee only followed in 1905, North Carolina and Oklahoma in 1907, Virginia in 1908, Arkansas in 1909, and Louisiana in 1910. Nowhere else had enacted such laws before the Great War broke out in 1914. The remaining holdouts were, except for the states created from Mexican territory in the 1860s, were states that failed to liberate their slaves before 1898 and were among the least industrialized in the country.

Racism was rampant in the North American continent. In the Union, blacks were not the prime targets after slavery was abolished nationwide in 1865. Segregation was visible, but blacks more or less had the same rights as their white counterparts. Casual racism from whites was instead directed at Asians, including frequent beatings and slurs being thrown around especially on the West Coast. On top of that, they could not become citizens, much less vote. Even more heavily targeted were Italian and Slavic immigrants who were deemed as an “inferior race of whites.” Casual and institutional racism by Anglo-Saxon Protestant Americans was noted in every aspect of life. Down South, the situation towards nonwhites was various. Whites were in control, but in Catholic dominated areas (California, Coahuilla, Cuba, New Chihuahua, New Sonora, and Puerto Rico), the hierarchy pit minorities against each other with half-whites (colored) receiving the most rights while those of half-native and half-black descent were at the bottom with next to no rights and were often sent to Indian reservations. In Texas and Louisiana, where Catholics didn’t hold a majority, but still held significant presence, mixed-raced or “colored” people were in the middle of three layers and while receiving many of the same rights as whites, faced some travel restrictions and segregation. All other minorities were at the bottom with a limited right to vote and could not travel out of state without a passbook. The Upper South (Kentucky, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Virginia) cut out the middle but restrictions at the bottom were less harsh. It was in the Deep South (Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, and Mississippi) where minorities, especially blacks, received the harshest treatment. Even after the national abolition of slavery, it was basically slavery in all but name for them as they could not vote, attend school, decide their own careers, or travel without passbooks. While Jews faced casual racism across the South, they did not face nearly as many legal restrictions.

Immigration to the United States from 1880 all the way to the breakout of the Great War in 1914 occurred in almost unprecedented numbers. From southern Europe came 4 million Italians. This was fueled by Southern Italy, including Sicily and Sardinia, where peasants suffered from severe hardship (bad soil, illiteracy, disease, malnutrition, exploitation, and violence). Initially, the number of Italians going to the USA and CSA was in line with each other’s population. But the lynching of 11 Italians in New Orleans 1891 largely ended Italian immigration to the CSA, with the vast majority (80-85%) entering the North American continent via Ellis Island in New York Harbor. They were greeted by the Statue of National Pride, as gifted by the German Empire in 1886. Most settled in urban centers such as New York where they arrived. In contrast, a much higher proportion of Jews (40-45%), went South due to Union alignment with Russia. Beginning in 1881, after the assassination of Alexander II, the Russian government placed harsh restrictions on the rights and mobility of Jews in its territory, restricting them to the Pale of Settlement. Anti-Semitic violence known as “pogroms” sanctioned by the czar drove two million Jews out of the Russian Empire and into North America. Approximately 60% entered via New York while 40% entered in Charleston Harbor in South Carolina, greeted by the Statue of Liberty (which was gifted by France). For Jews heading to the Union, New York City was the top destination and they often learned German alongside or before learning English. For those heading to the Confederacy, cosmopolitan centers such as Charleston (historically one of the largest Jewish communities in the Americas), Galveston (courtesy of the Galveston movement from 1907 to 1914), New Orleans, and South Florida, along with industrial centers in St. Louis and Richmond.

To a lesser extent, but nevertheless a highly visible one, German and Irish immigrants provided roughly one million immigrants apiece in this time period. Almost all of these groups went to the Union as the German Empire and the USA had close ties to each other - to the point where German was the second most commonly spoken language after English - and the Irish were seeking to get away from their British oppressors, who largely influenced the CSA. Immigrants from elsewhere in southern and Eastern Europe were proportionally split between the CSA and USA as their destinations, although those who intended to stay temporarily leaned more towards the Union due to perceived greater economic opportunity. While actively excluded from the Union under the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the CSA government was relatively welcoming towards Chinese, whom they sought after for labor in the Mississippi Delta region. Despite frequent casual racism from Confederate whites, most Chinese laborers (which only numbered a few thousand) ultimately stayed in the country.

By 1890, the majority of states and territories in the Union had passed compulsory education attendance laws, with the last four states being New Mexico (1891), Pennsylvania (1895), Indiana (1897), West Virginia (1897), Maryland (1902), and Delaware (1907). In contrast, only Cuba (1895), Kentucky (1896), Arizona (1899), and Puerto Rico (1899) had enacted compulsory school attendance laws before 1900. Missouri and Tennessee only followed in 1905, North Carolina and Oklahoma in 1907, Virginia in 1908, Arkansas in 1909, and Louisiana in 1910. Nowhere else had enacted such laws before the Great War broke out in 1914. The remaining holdouts were, except for the states created from Mexican territory in the 1860s, were states that failed to liberate their slaves before 1898 and were among the least industrialized in the country.

Racism was rampant in the North American continent. In the Union, blacks were not the prime targets after slavery was abolished nationwide in 1865. Segregation was visible, but blacks more or less had the same rights as their white counterparts. Casual racism from whites was instead directed at Asians, including frequent beatings and slurs being thrown around especially on the West Coast. On top of that, they could not become citizens, much less vote. Even more heavily targeted were Italian and Slavic immigrants who were deemed as an “inferior race of whites.” Casual and institutional racism by Anglo-Saxon Protestant Americans was noted in every aspect of life. Down South, the situation towards nonwhites was various. Whites were in control, but in Catholic dominated areas (California, Coahuilla, Cuba, New Chihuahua, New Sonora, and Puerto Rico), the hierarchy pit minorities against each other with half-whites (colored) receiving the most rights while those of half-native and half-black descent were at the bottom with next to no rights and were often sent to Indian reservations. In Texas and Louisiana, where Catholics didn’t hold a majority, but still held significant presence, mixed-raced or “colored” people were in the middle of three layers and while receiving many of the same rights as whites, faced some travel restrictions and segregation. All other minorities were at the bottom with a limited right to vote and could not travel out of state without a passbook. The Upper South (Kentucky, Missouri, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Tennessee, and Virginia) cut out the middle but restrictions at the bottom were less harsh. It was in the Deep South (Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, and Mississippi) where minorities, especially blacks, received the harshest treatment. Even after the national abolition of slavery, it was basically slavery in all but name for them as they could not vote, attend school, decide their own careers, or travel without passbooks. While Jews faced casual racism across the South, they did not face nearly as many legal restrictions.

Last edited:

Up next, the road to the Great War largely begins. Or at least less filler than last update.

Sorry for the lack of update, classes just started up again this week. Anyway, I made some revisions in earlier posts. The Battle of New York was officially replaced with that of the District of Columbia, so that makes more sense. Also, I eliminated the idea of the British being “useful idiots” for the Confederacy, instead having them also look out for their own interests and regain Washington territory that lies to the North and West of the Columbia River. Giving that up, especially Seattle, wasn’t exactly popular in OTL with the British, as the Minister who did that got fired for it. And after the devastating war for the USA here, it wouldn’t make sense for them to pursue another war less than 10 years later, even with alliances with Prussia and Russia solidified. So that got changed to more or less border skirmishes over the Florida Straits and a de facto alliance with Spain instead of a de jure one. A question, am I being too lenient about the rights of blacks outside the Deep South and understating how racist and discriminatory the CSA as a whole was? According to some people I talked to on another website, the CSA as a whole likely would’ve become an Apartheid State on steroids or the white would have had all the freed slaves deported back to Africa. Not sure which angle to take. Lastly, I may or may not need assistance with planning the Great War as I draw closer to it. I’m starting to write the next chapter now and should be published soon. So long for now.

-PGSBHurricane

-PGSBHurricane

Last edited:

Part 11: The USA Becomes the North American Power

Part 11: The USA Becomes the North American Power

The year 1901 was when the world began turning a corner. In the United States, it marked the start of a new era. This era began when President William McKinley was assassinated on September 6, 1901. Theodore Roosevelt, the acting vice president, took his place. McKinley had intended to keep William Jennings Bryan as his vice president heading into the 1900 election, but the two split on too many issues, such as silver coinage, for McKinley to reconsider him. They almost got into a physical altercation during a White House Dinner in 1899. In response, Thedore Roosevelt, who McKinley saw more eye to eye with, was chosen as the vice presidential candidate. He did not expect to fill such big shoes on March 4, 1901. But it took six months for him to realize that would not be the case.

After McKinley's assassination, Roosevelt promised to continue his policies of increasing American influence in foreign affairs, reflected with the following statement in 1905, "We have become a great nation, forced by the face of its greatness into relations with the other nations of the earth, and we must behave as beseems a people with such responsibilities." Roosevelt thought that the United States should uphold an international balance of power. He was also adamant in upholding the Monroe Doctrine to spite Confederate wishes, explicitly calling out the French Empire for its influence in Mexican affairs. Meanwhile, he viewed the British Empire as the biggest potential threat to the United States, fearing that the British would attempt to establish more bases in the Caribbean (with Montserrat already existing). Given this fear, Roosevelt pursued even closer relations with Britain’s arch rival Germany. Meanwhile, Roosevelt aimed to reform and expand the US military. The United States Army, with 26,000 men in 1890, was the smallest army among the major powers. By contrast, France's army had 542,000 soldiers. Secretary of War Elihu Root enlarged West Point, established the U.S. Army War College and the general staff, changed promotion procedures, organized schools for special branches of the service, devised the principle of rotating officers from staff to line, and increased the Army's connections to the National Guard. Roosevelt also made naval expansion a priority. The United States had the eighth largest navy in the world in 1904 and the sixth by 1907.

In December 1902, an Anglo-German-Italian blockade of Venezuela began over Venezuela owing money to European creditors. As the U.S. began to take notice and called for the Europeans to leave Venezuela, Roosevelt was soon able to come to an understanding with the Germans and Italians, but not the British, despite assuring the U.S. that they would not conquer Venezuela. Roosevelt remained suspicious of Britain’s ambitions and feared war with Great Britain. As a result, Roosevelt mobilized the U.S. fleet under the command of Admiral George Dewey in order to convince the British to arbitrate Venezuelan debts. Through American efforts, in order to keep the Confederacy out of the conflict, Venezuela reached a settlement with Britain in February 1903. In late 1904, more than a year after the Venezuela Crisis, Roosevelt announced the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, which stated that the U.S. exclusively would intervene in the finances of unstable Caribbean and Central American countries if they defaulted on their debts. This was meant as a warning to the British, French, and even Confederates (who were less interested in imperialism at the time). Soon after, the Dominican Republic was struggling to repay its debt to European creditors. Roosevelt reached an agreement with Dominican President Carlos Felipe Morales to take temporary control of the Dominican economy until the economy was stabilized.

In 1850, the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty between the United States and Britain, prohibited either from establishing exclusive control over a canal built in Central America. By the time fifty years had passed, American business, humanitarian and military interests were pursuing greater global involvement and a canal seemed of more importance than ever. McKinley pressed for a renegotiation of the treaty. The British were distracted by the Second Boer War, but relations between the two countries were as frosty as ever. Secretary of State John Hay and British ambassador, Julian Pauncefote, amazingly, agreed that the United States could control a future canal, provided that it was open to all shipping and was not fortified. McKinley was mildly satisfied with the terms, but the Senate overwhelmingly rejected them, demanding for US allowance to restrict use against enemies and to fortify the canal. Hay was embarrassed and immediately resigned. Negotiations under Roosevelt were much rockier and an embarrassed Roosevelt gave up on a Canal by the end of the first term. The British asked their close (but not as close as previously) allies, the CSA, if they wanted to pursue the canal, but the Confederate turned it down knowing that the canal was not a primary focus for their policy nor could they afford it. Thus, there was no Central American canal built until after the Great War.

The year 1901 was when the world began turning a corner. In the United States, it marked the start of a new era. This era began when President William McKinley was assassinated on September 6, 1901. Theodore Roosevelt, the acting vice president, took his place. McKinley had intended to keep William Jennings Bryan as his vice president heading into the 1900 election, but the two split on too many issues, such as silver coinage, for McKinley to reconsider him. They almost got into a physical altercation during a White House Dinner in 1899. In response, Thedore Roosevelt, who McKinley saw more eye to eye with, was chosen as the vice presidential candidate. He did not expect to fill such big shoes on March 4, 1901. But it took six months for him to realize that would not be the case.

After McKinley's assassination, Roosevelt promised to continue his policies of increasing American influence in foreign affairs, reflected with the following statement in 1905, "We have become a great nation, forced by the face of its greatness into relations with the other nations of the earth, and we must behave as beseems a people with such responsibilities." Roosevelt thought that the United States should uphold an international balance of power. He was also adamant in upholding the Monroe Doctrine to spite Confederate wishes, explicitly calling out the French Empire for its influence in Mexican affairs. Meanwhile, he viewed the British Empire as the biggest potential threat to the United States, fearing that the British would attempt to establish more bases in the Caribbean (with Montserrat already existing). Given this fear, Roosevelt pursued even closer relations with Britain’s arch rival Germany. Meanwhile, Roosevelt aimed to reform and expand the US military. The United States Army, with 26,000 men in 1890, was the smallest army among the major powers. By contrast, France's army had 542,000 soldiers. Secretary of War Elihu Root enlarged West Point, established the U.S. Army War College and the general staff, changed promotion procedures, organized schools for special branches of the service, devised the principle of rotating officers from staff to line, and increased the Army's connections to the National Guard. Roosevelt also made naval expansion a priority. The United States had the eighth largest navy in the world in 1904 and the sixth by 1907.

In December 1902, an Anglo-German-Italian blockade of Venezuela began over Venezuela owing money to European creditors. As the U.S. began to take notice and called for the Europeans to leave Venezuela, Roosevelt was soon able to come to an understanding with the Germans and Italians, but not the British, despite assuring the U.S. that they would not conquer Venezuela. Roosevelt remained suspicious of Britain’s ambitions and feared war with Great Britain. As a result, Roosevelt mobilized the U.S. fleet under the command of Admiral George Dewey in order to convince the British to arbitrate Venezuelan debts. Through American efforts, in order to keep the Confederacy out of the conflict, Venezuela reached a settlement with Britain in February 1903. In late 1904, more than a year after the Venezuela Crisis, Roosevelt announced the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, which stated that the U.S. exclusively would intervene in the finances of unstable Caribbean and Central American countries if they defaulted on their debts. This was meant as a warning to the British, French, and even Confederates (who were less interested in imperialism at the time). Soon after, the Dominican Republic was struggling to repay its debt to European creditors. Roosevelt reached an agreement with Dominican President Carlos Felipe Morales to take temporary control of the Dominican economy until the economy was stabilized.

In 1850, the Clayton-Bulwer Treaty between the United States and Britain, prohibited either from establishing exclusive control over a canal built in Central America. By the time fifty years had passed, American business, humanitarian and military interests were pursuing greater global involvement and a canal seemed of more importance than ever. McKinley pressed for a renegotiation of the treaty. The British were distracted by the Second Boer War, but relations between the two countries were as frosty as ever. Secretary of State John Hay and British ambassador, Julian Pauncefote, amazingly, agreed that the United States could control a future canal, provided that it was open to all shipping and was not fortified. McKinley was mildly satisfied with the terms, but the Senate overwhelmingly rejected them, demanding for US allowance to restrict use against enemies and to fortify the canal. Hay was embarrassed and immediately resigned. Negotiations under Roosevelt were much rockier and an embarrassed Roosevelt gave up on a Canal by the end of the first term. The British asked their close (but not as close as previously) allies, the CSA, if they wanted to pursue the canal, but the Confederate turned it down knowing that the canal was not a primary focus for their policy nor could they afford it. Thus, there was no Central American canal built until after the Great War.

Last edited:

SpaceOrbisGaming

Banned

On October 30, the Virginius started toward Cuba from Jamaica. The Spanish figured this out and sent the warship Tornado to capture it. They spotted it over open waters the same day, just 6 miles off the shore from Cuba. The Tornado fired at the Virginius several times, causing the top deck to suffer from severe damage. Captain Fry surrendered the ship, knowing it could not outrun the rivaling Tornado. After securing the ship, the Spanish sailed the vessel to Santiago de Cuba, taking the entire crew prisoner and ordering them to be put on trial as pirates. The entire Virginius crew was found guilty of piracy and sentenced to death. Between November 4 and November 8, all 53 ship members were executed mostly by firing squad, including Captain Fry himself, plus an additional four mercenaries who were executed without trial.

With near-universal outrage among free white Confederates, the Confederate Congress declared war on Spain on November 11, 187.

This is clearly not right you need to fix this asap. I'm guessing the year is 1870, not 187.

SpaceOrbisGaming

Banned

All of this meant that southern cotton was less viable to the European (and even the USA) market. Cotton prices fell domestically and shipments across the world plummeted. With the depression, ambitious railroad building programs crashed across the CSA, South, leaving most states deep in debt and burdened with heavy taxes. Between this and the reduced viability of slavery, a common response to this was retrenchment, with spending at record lows. In the Upper States of Kentucky, Missouri, and Virginia, where cotton was not as prosperous to start with and slaves were seen as luxury items, there were even debates about emancipating slaves entirely. Also in those states, cuts in wages and bad working conditions led to a Great Railroad Strike in 1877 beginning in Martinsburg, Virginia. However, this was brutally put down by government troops and was characterized in the press as an insurrection rather than an act of desperation. Similar strikes happened to its northern neighbor. By 1878, the damage the Panic had caused was done and would shape the country and its institutions (including slavery) for decades to come. By 1880, five states - Arizona, Coahuila, New Chichuaha, New Sonora, and South California - had abolished slavery entirely and two more (Kentucky and Missouri) plus Indian Territory had just passed gradual emancipation acts. These states stood alone with their futures in the air. Would they be the new leaders of an industrialized tomorrow or would they be shunned by the rest of the agrarian Confederacy?

Cool, my home town/city is in this story. Besides the fact it's in Virginia and not West Virginia that is.

I meant 1872 and I fixed it so it should be good now.This is clearly not right you need to fix this asap. I'm guessing the year is 1870, not 187.

Threadmarks

View all 16 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Part 3: The Treaty of Richmond Part 4: The Aftermath of the Union Part 5: The Start of Confederate Expansion Part 6: The Cuba Question Part 12: The Rise of the Entente and the Deconstruction of the Confederacy Part 13: The Hapsburgs and The Beginning of The End Part 14: The Beginning of The Great War Part 15: Culture of the Early Twentieth Century

Share: