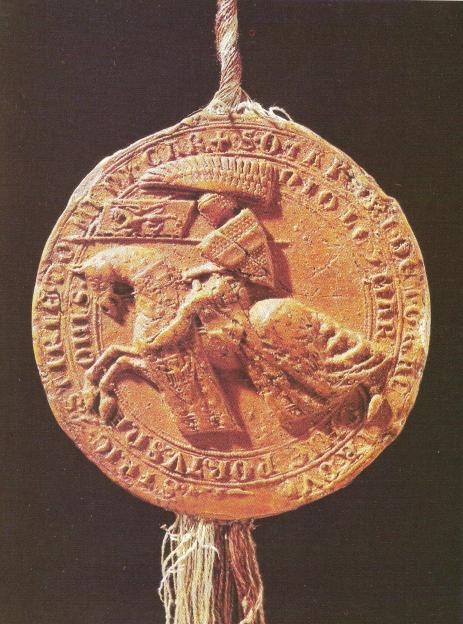

Sultan Ibrahim son of Mehmet

Part 34: Ibrahim, the Powerless and the Conqueror

Ibrahim son of Mehmet was not in a good situation as Sultan of Rum when he was crowned in 1468: he was very young, only nine years of age, and at the head of a state that was struggling to hold onto its recent conquests in the Balkans and contend with its powerful neighbors, namely the continually resurgent Sultanate of the Mameluks to his south. In addition to all these difficulties, he was barely even in control of the state, with his youth a fine excuse for his close father figure Ismail al-Rumi to function as the regent of the state, having risen very rapidly from his earlier lower station as Vizier of Bread. The early years of Ibrahim’s reign are defined by his lack of power and influence, with Ismail granting ever more powers to local nobles and magnates, settling decentralized Kurdish bands in the Balkans to hold onto the rebellious new provinces, and making deals himself with the King of Georgia, Bagrat VI, who was in the process of reconstructing the fragmented remnants of his kingdom after its occupation by the White Tatars. Using his knowledge and influence from his former position as Vizier of Bread (by 1468 he was no longer Vizier of Bread, but had instead appointed a local Turcoman from Iconium to the position to replace him now that he was regent), Ismail supplied Bagrat with notable levies of grain and other produce, helping to feed the soldiers in the service of the Georgian monarch who were so integral to retrieving the heartland of Georgia and Abkhazia from Burilgi’s White Tatars and were now central to the process of rebuilding what was destroyed by the steppe conquerors in their invasion across the mountains. Churches and cities had to be rebuilt, and the produce of the fertile farmlands of Anatolia helped the great king handle this great challenge, and this closer relationship helped to mend the ties riven apart by inaction on the part of many of the recent Sultans. Georgia and Rum were to be allies once again.

While Ismail’s leadership helped to heal the relationship between Rum and Georgia, he was much less effective in the south, where the two most stable powers of the day, the Sultanates of Iconium and Cairo, quarreled for influence in the squabbling states of Iraq and southern Iran. While Ilkhanate rule had collapsed in the region with the conquest of Burilgi, regular raids from the northern remnant of Mongol control in the Iranian highlands had kept down many of the smaller states in Fars, Hormuz, Balochestan, Basra, and Baghdad, stopping any real active development on the part of the warlord states of southern Iran, but as Burilgi’s Empire collapsed in on itself in Tartary and Turkestan, the last remnant of support for the meager Ilkhan state collapsed with it. By 1468, the only pocket of remaining Mongol control in Iran was centered on a thin strip of land from the Ilkhan capital of Sultaniyeh stretching eastward to Rayy, the remainder of the mountainous land having fallen completely beyond their control, now ruled by local Shi’i magnates and clergy or by Turcic or Iranian nomadic warlords. With Iran essentially a non-entity among the Middle Eastern powers, Rum and Egypt turned their eyes to influence the struggling statelings of the easily reachable south.

The descendant of the warlord who declared himself Sultan of Baghdad, a Persian by the name of Mahmoud al-Baghdadi, was a very imposing man, his long black beard one and tall stature commonly remarked upon by the records of the time. His father, Uthman, paid tribute to the Ilkhan in Sultaniyeh, but upon his death, the newly crowned Mahmoud cut off all ties with the Mongol overlords and began a policy of expansionism, trying to establish a powerful state centered on Iraq. He very quickly consolidated the south of Iraq, putting down the rebellious emir of Basra with black powder weaponry, and began a push northwards that put him at odds with the Sultanate of Rum, whose control over the Jazira was uncontested. Mahmoud attempted to make in-roads into the Jazira by supplying members of the Kurdish bands who were exiled from the region following Rum’s conquest, but ultimately this did nothing, and his focus on eliminating any threat from the north had to be placated in another way. In 1469, Mahmoud al-Baghdadi received a missive from the court of the Sultan of the Mameluks in Cairo, which promised the Sultan protection in the case of any invasion by the Sultanate of Rum, as well as a long litany of rather symbolic protections and assurances awarded Mahmoud by the Caliph in Cairo. It would seem that Iraq would be in the hands of the Mameluks in one way or another, though this was challenged by an emissary sent personally by Sultan Ibrahim of Rum (though it is far more likely that the emissary was sent on the orders of Ismail al-Rumi) in 1472, which assured Sultan Mahmoud al-Baghdadi that there was no intention on the part of the Sultan of Rum to invade his holdings in Mesopotamia, and ensuring that the Sultanate of Rum would provide Kurdish levies to protect the defenseless Iraqi heartland from incursion from the Iranian plateau. Mahmoud al-Baghdadi seemed to have become a focus of much attention almost overnight, and he appreciated this, attempting to play the two powers off of one another in local politics. The Sultanate of Rum also made in-roads into Iran, but the more ideologically defined Shi’i magnates there resisted the influence of either of the Sunni powers, and the merchant-dominated regions of Hormuz and Fars fell readily into the sphere of influence of the Mameluk Sultanate of Cairo. In the foreign stage, Ismail al-Rumi and his child Sultan Ibrahim were failing to gain much influence, and were failing to expand the scope of the state. At first, this did not seem like an issue; while abroad, the influence of the Sultanate of Rum was declining, at home and with regards to their close allies in the Caucasus and Balkans, everything was alright. But, with the coming of famine in 1475 and an attempt to revive the alliance of the Balkans in 1478, it was obvious that something had to be done to reassert the power of the Sultanate of Rum.

Sultan Ibrahim (here depicted older than he really would have been) and Vizier Ismail meeting with Venetian shipmasters

The planning was already well under way in the earlier part of the 1470s. Emissaries were sent to Venice and Genoa, and new levies were called up from the iqtas of the nobles of Rum. The aged Ismail al-Rumi seemed to be gearing up to something, but what exactly it was was unclear to all those who noticed it. The young Sultan Ibrahim was now a young adult, able to assert himself more, but even he was quiet on the plans that were being implemented. It would seem that they did not want any news coming out about what the young man and the old man wanted. Then Ismail al-Rumi died in 1479, leaving the 20 year old Sultan Ibrahim to make do with what was already done. In late 1479, war was declared by Sultan Ibrahim on the Eastern Roman Empire, bringing a new war to the Balkans. In the initial part of the 15th century, the relationship between the Eastern Roman Empire and the Sultanate of Rum was cordial but challenged, with the Roman Emperors knowing the obvious fact that the Sultans of Rum were by far their senior. The Roman Empire controlled only disparate islands and peninsulas, barely controlling their section of Asia Minor that was more or less under the rule of independently acting local magnates who only on occasion sent taxes to Constantinople, and by the 1450s, Constantinople had to pay tribute to the Sultanate of Rum, for Turcoman and Kurdish mercenaries who protected the northern fringes of their meager holdings from Slavic incursion. The newly crowned Emperor of Rome, Constantine, broke off this payment in 1466, but nothing could be done about it with the powerless and aged Sultan who had to contend with holding onto his newly conquered territories in the Balkans. But Ibrahim, the clever and strong young man who had grown into his own after years of powerlessness in a state dominated by the Roman Ismail, was able to finally put meaning behind the years of rhetoric and argument that had dominated the politics of the Aegean and Anatolia.

So war had come to the Balkans yet again, and this time it was the great conflict between the last remnant of the greatest empire on earth and the rising star of the Turcs, but who was involved in this conflict, and how were the factions arrayed? Quite obviously, the war can be understood as being between two camps: that which supported Basileos Constantine and the Eastern Roman Empire, and that which supported Sultan Ibrahim and the Sultanate of Rum. On the Roman side was the revived Balkan alliance of Bulgaria on the Danube and the smaller principalities in Serbia, all subject to the Patriarch of Constantinople and all committed to protecting the leader of Eastern Christendom. On the Turcoman side was the vassal of Nishava and, most surprisingly, the Most Serene Republic itself. While Venice and Genoa were quite recently embroiled in conflict in northern Italy as part of the Hundred Years War, Venice saw the opportunity to rapidly expand their control over the trade of the Eastern Mediterranean and sided with the Sultan against the Basileos, promised unchallenged ownership over Crete, the Peloponnese, and the islands of the Aegean, as well as special trading rights, if they assisted the Sultanate of Rum with naval operations and some overland support. The Kingdom of Georgia and their vassal in Trebizond were in a strange and precarious position: on the one hand, they were closely allied with the Sultanate of Rum, and thusly would realistically side with the Turcs against the Romans, but they were also subject to the Patriarch of Constantinople and saw the Basileos of Rome as the leader of Eastern Christendom, and so could not in good conscience support the violent invasion of the state they look up to for religious and ideological leadership. Georgia remained neutral in the war.

This war was a considerably shorter affair than the grueling conflict that Ibrahim’s ostensible father waged in the Balkans decades earlier. The loose alliance of Balkan states was rather unstable, and was split apart when the Hungarian crown attempted an invasion of Wallachia in 1480 to put down a peasant uprising there, something which the Bulgarians felt was a fundamental challenge to their stability, while the smaller Serbian principalities felt that Hungarian influence was not too major of a challenge to focus on. Bulgarian forces had pushed deep into Turcish territory by late 1480, but with the internal squabbles between the Slavic principalities and the last-minute decision to focus on the defense of the northern Danube frontier, the Bulgarians began to fall back, as joint Turcoman-Venetian offensives on the city of Constantinople itself challenge the safety and control of the Eastern Roman Empire. Hungarian forces pushed deep into Wallachia as Turcoman forces pushed northwards to the Danube, capturing the Bulgarian capital at Sofiya in 1480, and completely occupying the Danubian lowlands by early 1482, with the Serbian principalities unable to do much of anything other than protect the Kniaz of Bulgaria as he flees to Belgrad.

With the northern frontier secured, the siege on Constantinople could be honed in on by Sultan Ibrahim. Great cannons, the inheritance of the great developments in black powder begun first by the Chinese so long ago and brought to the dar al-Islam by the Mongol conquerors, were blasting the immense Theodosian Walls of Constantinople since the siege began in 1480, with smaller arms from the push to the Danube brought down by early 1481, and regular attacks on the western end of the city by Turcoman and Kurdish pikemen and nomads and on the eastern coast of the city by Venetian ships trying to destroy the ports and blockade any access into the city. The Theodosian Walls fell by 1482, with the forces of Sultan Ibrahim pouring into the glorious city and capturing it for the Sultan of Rum. The fate of Basileos Constantine Komnenos is uncertain and obscure, though there is a folk tradition that he took up a sword and himself fought in the defense of the city, but there is no real evidence for this narrative. Sultan Ibrahim was a young man when he achieved that which was only a dream for so many before him, only 23 years old, his beard short and a vibrant black on his high cheekboned face as he strode into the city of the world’s desire. In truth, he cannot take credit for this; the planning and preparation was, for the most part, done by Ismail al-Rumi, the conniving Roman who took power from himself and his father, but he took credit nonetheless, and almost immediately moved his state’s capital to the great city of the Romans.

"Verily you shall conquer Constantinople. What a wonderful leader will her leader be, and what a wonderful army will that army be!"

-A tradition of the Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Sorry for the long wait on this one... I want to have a more regular schedule for releasing updates to the timeline, but it is all too easy to get busy and focused on other things... I hope this deeper look into the world of the late 15th century and the coming of one of the most momentous events in world history makes up for the delay! Thank you all for reading my timeline, and I hope I only continue to make an ever more interesting timeline for you all to read!