Special Update 4: Minorities in Burilgi's World

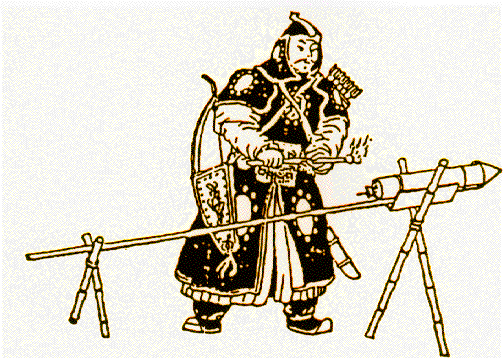

With the death of Khukir Burilgi Emir Khan, the whole world over was changed, redefined. Him and his conquests represent both a refutation of the old Mongol order and a continuation of it, bringing the synthesis of the Mongol Empire and its culture into the 15th century. To truly appreciate the ways this immense state has redefined so many lives, one can examine the cultural roles of different ethnic groups, minorities within an empire so vast that just about everyone is a minority. But, in truth, there is one group that holds the majority of power: the group commonly called Turco-Mongols by contemporary historians. Burilgi himself was a great representative of this cultural fusion of Turc and Mongol, with his Bashkir mother and Mongol father. Whether they call themselves Tatars, Bashkirs, Kirghiz, or Uzbeks, the vast expanse of steppe and sand from the Crimean Peninsula to the Tianshan mountains is inhabited by the heirs of Temujin and Burilgi, the inheritors of extensive Central Asian empires. With his capital at Sarai on the Volga, it was this new Turco-Mongol tradition that began the administration of his empire, inheriting the extensive networks of the Mongol Empire as well as the literate culture of Iran. Within the Burilgid empire proper, these Turco-Mongols form the vast majority, but to truly understand this new world their interactions with other groups must be examined.

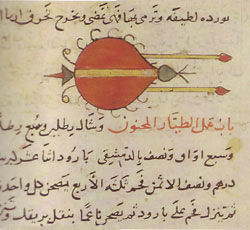

Although a Turcic group just like the Turco-Mongols, the Turcs of the Tarim Basin (properly referred to as Tarim Turcs, Hui Turcs (from a Chinese perspective), or Uyghurs (though the latter is not especially popular)) retained a distinct identity from the remainder of the Burilgid domain, primarily due to their entrenched literate culture and distinct history beyond the Tianshan. On a map, it may seem that the Tarim Basin was a backward in relation to the rest of Burilgi’s empire, but in truth it became a bustling center of culture and trade. The cities of Kashgar, Yarkand, Turfan, and others, after recovering from the devastation of Burilgi’s invasion, increasingly became points of interaction between the struggling Great Yuan and the states to the west, with more Chinese seen in these Turcic cities since the end of Chinese rulership over the Tarim Basin. Furthermore, the Tarim Basin is the birthplace of the printing press, a gift of the east so readily loved by Burilgi himself. Tarim Turcs found their way all the way to Sarai as mechanics for printing presses, with the machine itself developed for the printing of the Arabic script. This transition wasn’t too difficult: they had already been designed for writing the Hui Turc language, ultimately derived from the Syriac language’s writing system, resembled Arabic turned on its side. The first thing printed using a press west of the Tianshan mountains was an imperial decree by Burilgi’s sadly unnamed vizier of Sarai that restricted trade coming into the city with an outbreak of disease that year. The second thing printed was a copy of the first five chapters of the Shahnameh by Ferdowsi. The third was a Qur’an. The Tarim Turcs could be proud to contribute to the literary culture of Central Asia as their derivation of a Chinese invention spread from Sarai out into Tatary and Transoxiana.

Another Turcic group, the Turcomen of Khurasan did not benefit so greatly from Burilgi’s conquests as the Tarim Turcs. They have more cultural connections with Iran than with the Mongols, and as such did not have the cultural foundations to be part of the majority Turco-Mongol culture of the empire, this division made only worse by Burilgi’s slaughter of Khurasan. Thousands of Turcomen died at the swords of his armies, rapidly depopulating the whole of the region. The already very pastoralist Turcomen reverted to even more basal and isolated forms of pastoralism, as the cities in Khurasan were destroyed and left as nothing but husks of their former selves. The Turcomen were violently forced out of the society built in Burilgi’s empire.

This fate was not shared by the Persian speakers of the Iranian Plateau and Transoxiana, who benefited greatly by the sudden conquests of the Burilgid Empire. Persians formed the backbone of the Burilgid administration (albeit how fledgling it was during Burilgi’s conquests), large numbers of them moving from Transoxiana to other parts of the empire. Khurasan received an influx of agrarian Persian immigrants following Burilgi’s push into the Iranian plateau, namely from Transoxiana. The Iranian Plateau itself was devastated by Burilgi’s invasion, but it remains independent from the Burilgid Empire and thusly Persians retain much in the way of the economic and cultural influence they had before his conquests. While the Ilkhan is always ready to claim that they are Mongols, and while this is true, the ruling elite of the rump Ilkhanate has become almost completely nativized, enmeshed with the populace of the state. While Persian Muslims dominate the upper class affairs of both the Ilkhanate and the Burilgid Empire, Zoroastrian Persians have become increasingly disadvantaged, targets of massacres by Burilgi’s armies and increasingly pushed out of public life in the land they once ruled over. Ilkhan Uthman bin Abu Said is almost fanatically Sunni, and punished Shi’is and Zoroastrians equally. His repression of Zoroastrians has caused mass migrations of the mostly agrarian minority into lands neighboring the rump Ilkhanate, creating refugee Zoroastrian communities in newly independent Fars and in isolated valleys of the Iranian plateau. Meanwhile, Shi’is come to dominate in the fringe regions of Iran, namely Arran and southern Khurasan. Movements made up of Zoroastrians and Shi’i Persians targeted against the Ilkhan and his government are increasingly prominent, though always violently repressed.

Another group which retained some modicum of political independence were the Armenians, namely Persianized Armenian Muslims and Armenian Christians. Both communities rose up when Burilgi invaded the Ilkhanate, in support of the Burilgid forces in the Caucasus, but in the end it was only the Armenian Muslims which benefited greatly from the conquest. As a reward for their support during the push through the north into Iran, the community of Persianized Armenian Muslims, headed by a small group of Armenian Muslim nobility from the former Ilkhan rule over the region, were granted the title of Armenshah and rulership over the territory around Lake Sevan and the city of Yerevan. Armenian Christians, on the other hand, were granted nothing; this is despite them making up the vast majority of the Armenian rebels who fought against the Ilkhanate during the Burilgid invasion. The community of Armenian Christians is disapproving of the rulership of the Armenshah, instead desiring to restore Christian rulership over the whole of Armenia. A sort of protracted resistance war between the Armenshah and rebellious Christians (many of them based out of Mount Ararat) defines Armenian politics, with the Armenshah attempting to suppress it without drawing the attention of the Ilkhan or of Burilgi (and now, his successor). He does not want Armenia to become like Iran or Khurasan.

Georgia is a very different story. The Kingdom of Georgia collapsed to the onslaught of the Burilgid armies as they pushed across the Caucasus, fleeing to the more southerly cities and defended by the force of arms of the Sultanate of Rum. They resisted Burilgi’s conquest, and so, instead of being granted autonomy like the Ilkhanate or the Armenshah, Georgia was placed under the rulership of a Turcic tribe loyal to Burilgi: the White Tatars. The exact origin of this group is obscure, but presumably they are ultimately a result of Mongol migration into the region of the Pontic-Caspian Steppe, and the subsequent intermixing with the local Turcic population. The White Tatars were predominately Sunni Muslim, and when awarded the land of Georgia by Burilgi they began to suppress Christian practice and attract Turcic settlement from north of the Caucasus. The ringing of bells in Georgian churches was banned, as was the use of the recently spread printing press for printing Bibles. The Georgian populace bristled at many of these practices, but generally were not especially resistant to the nomadic rulership of the country. In fact, many of the peasants, especially in the southern regions of the White Tatar Horde, paid taxes and tribute to both the King of Georgia and to the White Tatar Emir!

Jews were already widespread throughout the lands of Burilgi’s conquests, and his expansive empire only allowed Jewish communities to spread further. Turcic Judaism, that being the sort of Judaism practiced formerly by the Khazars, seems to have completely died out by the time of Burilgi’s conquest of the north Caucasus, with whatever remnants of it prominent in the Neo-Khazar Confederacy stamped out for the final time by Burilgi’s armies. In its stead, two distinct Jewish communities became increasingly widespread: Mizrahim, more specifically Judeo-Persians, and Karaim from Crimea. The Jewish communities of greater Iran actually benefited greatly from the conquests of Burilgi, primarily as they became the means of trade within and without his state. Persian was the lingua franca, and the Persian Jews, who spoke both Persian and their unique communal dialects (whether from Ray or Bukhara or the region of Mazandaran) took great advantage of the smoothing out of trade barriers. While the Chinese may have come to the Tarim cities to do trade, it was often with Persian Jews that they were trading with, not with Turcic Muslims. The Karaim, the unique Turcic Jewish community of Crimea who did not acknowledge the Talmud as a religious text of any spiritual import, began to spread out from Crimea and into the Burilgid territories in Ukraine and the north Caucasus, but at this point they remained only a notable minority. However, Karaim who traveled into the coastal cities of the Black Sea often were the intermediaries between the local Moldavian elite and their Muslim Turco-Mongol overlords.

The last remaining minority group of Burilgi’s Empire are those peoples in its westernmost fringes: the Russians. Kiev is but a burnt out husk after the constant grinding warfare at its gates and at its walls, but the people of Rus’ retain their distinct culture and identity. While the White Tatars in Georgia may be suppressing Christian practice, Burilgi’s empire never implemented laws to suppress the Christians, and in fact the collapse of the Golden Horde and the expansion of Burilgi’s state did benefit certain Russians. Namely, the Russian merchants who traded primarily in furs, lumber, and agrarian products had a wide market opened up to them, and for the first time in history Russians had somewhat regular access to the Siberian furs that so enticed them. However, this came at the cost of political independence and semi-regular massacres, as well as raids from the Burilgid Empire into the still independent Russian principalities between the Turco-Mongol state and Poland and Lithuania. Novgorod attempts to advocate for the interests of the Russian minority in the Burilgid Empire, but is relatively powerless to do so, even as not insignificant numbers of Russians, especially those in the easternmost cities, begin to turn to Mecca when they pray, and forego the reverence for icons of the saints…

With the nearby tin mines and coastal plains for agriculture, the city is a good place for a capital of a kingdom, though I personally favor a northerly spot like Kuala Selangor as the soil is better there, but I digress.

With the nearby tin mines and coastal plains for agriculture, the city is a good place for a capital of a kingdom, though I personally favor a northerly spot like Kuala Selangor as the soil is better there, but I digress.