You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Red Crowns: The World of Imperial Socialism

- Thread starter Major Crimson

- Start date

A shame Bonaparte didn't win, but I guess the conflict has to come from somewhere. I'll be eagerly waiting for the victory of imperial socialism over the reactionary forces.

Yes tis truly a shame, Bonapartes message seemed the better for safe-guarding French freedoms, but his ties with "the ancestral enemy" killed his chances. However should General Revanche falter, we might yet still see him gain the throne.

Also our names are hilariously close

Update in the works and nearly done, definitely up tomorrow I swear to god! Also posted a little infobox from the TL over in the Alternate Wikipedia Infoboxes thread with SOME SPOILERS so go have a look at that if you don't mind receiving a few hints about the future of the TL and of ImpSoc ideology particularly.

So Ladies and Gentlemen which Chaos God do we sacrifice the major to if he doesn't post tomorrow ?Update in the works and nearly done, definitely up tomorrow I swear to god! Also posted a little infobox from the TL over in the Alternate Wikipedia Infoboxes thread with SOME SPOILERS so go have a look at that if you don't mind receiving a few hints about the future of the TL and of ImpSoc ideology particularly.

TheHolyInquisition

Banned

The Queen, of course!So Ladies and Gentlemen which Chaos God do we sacrifice the major to if he doesn't post tomorrow ?

XV - New Beginnings and Overdue Endings

Chapter Eighteen

New Beginnings and Overdue Endings

Extract from: Between the Wars: 1895-1909 New Beginnings and Overdue Endings

By: Mike Cavendish, 2011, Penguin Publishing

The so called “first interwar period” of 1895-1909 was, despite the name, a time of massive upheavals. With the Spanish and Chinese Empires suffering near collapse, France restoring her reputation, reform in Germany, the signing of not one but three major global alliances and the start of the Pan-Nationalist movement. It is the later of which we will be focusing on today as the phenomenon is quite boring to some and quite complicated to most. Pan-Nationalism is effectively a followup to the civic nationalism of the mid 19th century. As Italy, Japan and Germany united around a new national identity and evolved from divided independant states into united countries, so too did places like South America and Scandinavia rally around “pan-national” ideas. The idea was born in Sweden and Denmark where Nordic unification had been a nascent concept since the Danes were abandoned to fight (and lose) the Schleswig War against Prussia and Austria in 1864. As the 20th century appeared on the horizon however, the perceived Swedish “abandonment” seemed to be less and less important. On Sweden's eastern border, the Russian Empire was becoming more and more militarised, in France and Austria too, the people of Scandinavia saw looming, expansionist foes looking for easy prey. It is largely as a response to this external pressure but also, no doubt, due to the cultural renaissance in theatre and music that spanned the great northern wastes in the 1880s and 90s. More and more collaboration between Swedish writers, Norwegian actors and Danish musicians (or any variation on that theme) helped build on the familial and fraternal bonds that had always existed across borders. Unity was coming, though no one at the time truly saw it coming.“Scandinavianism” as the ideas of unification were known, was not a newfound idea. The “Kalmar Union”, founded in the Swedish city of Kalmar, was a personal union of the three Kingdoms under a single monarch that existed throughout the 15th century. Norway, once a possession of the Danish King, was now in union with Sweden and thus deferred to Stockholm on most matters. Hans Christian Anderson had been a major proponent during the 1840s and 50s. In 1879 an alliance of Danish, Swedish and Norwegian settlers founded the town of Dannevirke in New Zealand whilst Swedish King Oscar I had been a major proponent of the ideology since his ascension. As of 1895, there was broad ideological unity as the governments of all three Scandinavian countries came from liberal, centrist parties. It was Danish Council President (Prime Minister) Johan Deutzer that first proposed the formation of the Nordic Union in its modern form. The Swedes had always been receptive to the idea, their size and wealth meant that they would likely hold the most influence in any Scandinavian state and their economic interests were well served by new markets. The Norwegians meanwhile were often little more than Swedish vassals by 1895 and lept at the chance of a union, hoping that they might earn greater autonomy and influence within it or at very least dilute the influence that the Swedes held over them. For the Danes, meanwhile, it took more persuading. Their rivalry with Sweden was a millennia old and they would likely see their role reduced by unification with their larger, eastern neighbour. There was still sense to the move however, the loss of Holstein and Schleswig to Germany some decades ago proved how vulnerable the small country was, whilst their waning economy would also benefit from the injection of workers, goods and potential consumers that Sweden would provide. Deutzer had been won over to the idea by seeing the success and liberalisation occurring in Italy, Germany and Japan and hoped to recreate that national reinvention in Scandinavia. Inviting ministers and diplomats from what was then the United Kingdoms of Sweden and Norway to Copenhagen in May 1895, he outlined a series of proposals for open borders, a monetary union, a military alliance and, in time, political integration. The initial reception was extremely positive and Swedish Foreign Minister Ludwig Douglas, who had met personally with Deutzer, wrote to his King that: “The Danes are confident but willing to make concessions, they seem to view the union as not just a boon for all our Kingdoms but as a near-necessity so that they might counter the influence and threat emerging across Europe. This can only be good for Sweden”. Both the Swedish King and Prime Minister were pleased at the proposal and agreed, as did the First Minister of Norway.

This poster, depicting soldiers from each of the three countries holding hands, was circulated continually by pro-Union campaigners and politicians.

Talks began just weeks later and of course there were a litany of disagreements, at what rate would the new currency be pegged? Would Norway be represented as an independent Kingdom or as a part of Sweden? Would trade be allowed to move across borders? And if so would regulations be normalised? For six months, difficult talks were held which, at several points, showed signs of breaking down but bit by bit compromises were reached. The new currency would be independant from either the Swedish or Danish Krona/Krone but pegged at the Swedish rate, which was higher. Norway would meet as a separate Kingdom to Sweden but defer to the Swedish government on any international or military matters as well as having less representation than the other, larger kingdoms. Trade would move across borders and there would be a consultation on new laws that would have to be passed separately through all three separate parliaments. Finally, on December 2nd 1895, the Prime Minister of Sweden, Prime Ministers of Sweden and Norway met with the Council President of Denmark in Kalmar and made a joint announcement that the Nordic Union would come into force on the 1st of January the following year. The borders of the three nations were to be opened, a new currency known simply as the Krona (or Crown) was to be phased in before fully replacing national currencies in 1901 and the three countries would be bound to help one another in any war, defensive or offensive. The council also provided a meeting place where the ministers and monarchs could discuss issues of state, as they would do at yearly conventions from 1896 onwards. The old flag of the Kalmar union, a red cross on yellow, was flown as the symbol of this new union and it soon became fashionable to fly them alongside national flags. It even entered into fashion as pins, ribbons and most garishly bedsheets and curtains. Before long, the cultural exchange that had started to grow between the nations grew and grew and it was common to find Norwegian liquor and Swedish beer in any Danish pub whilst libraries were stocked in books of three languages and children at school near the borders went on exchange trips to “sister schools”. The Nordic Union was an artificial one to be sure but one that was accompanied by a genuine and popular growth, the people of Scandinavia had always been close in spirit and their old rivalries and conflicts seemed less and less memorable by the day. In his speech announcing the union, Swedish King Oscar II made specific reference to the movement as Pan-National, stating that “We will always be Swedes, we will always be Danes, we will always be Norwegians. Throughout it all however, we will be Nords as well. Three nations but one pan-nation, a union greater than any of its parts. Oscar’s personal motto “Brödrafolkens väl”, literally meaning “Welfare of the Brother peoples” would become the motto of the new union and encapsulated the feeling of the time. Whilst Russia was the motherland and Germany the fatherland, Scandinavia would be the brothercountry, a union of fraternal equals. The Union of 1896 was far, far from a united country however. There was yet no united parliament or permanent council, no united economic or foreign policy. The union was mostly comparable to the Deutscher Bund that preceded the German Empire. It is laughable that, even today, there have been more wars between Denmark and Sweden than any two other countries, bar of course Britain and France…

Extract from: End of Empires: How the Mighty Fell

By: Betsy Tejo, Liberty Universiy Press, 1990

The first conflict to emerge in the post-Short War World was a niche one and often forgotten today outside of the nations that took part. The Spanish War or, in Spanish “Guerra de los Dos Océanos”, was a conflict that took place from June 1897 to August of that same year and saw the wholesale destruction of the Spanish Empire outside of Africa. Spain had been in serious decline since the Napoleonic Wars. With the loss of her Spanish colonies she went from the original empire “upon which the sun never set” to a ragged, second class power, wracked by civil war and economic woes. Her most prized imperial holdings were the Phillipines and Cuba, distant but lucrative colonies dangerously close to other, ascendant great powers. Whilst many look to the Cuban Revolution of 1895 (which saw local landlords rise up against the Spanish) as the spark that lit the war, in truth it seems inevitable. The convergence of American and Japanese interests centered around their shared relationship with Great Britain. The Americans had always been strongly tied both culturally and economically to the British, whilst the Japanese were their newest and closest allies. From the end of the Short War the three were left as the only major powers in the pacific. The British, from their bases in the Sandwich Islands (known to the natives as Hawaii), Australasia, Borneo, Hong Kong and Singapore, were top dog. The Royal Navy was undisputed master of the seas and had ports across the Pacific. The Americans and Japanese were content with this; the USA was hegemon of the Americas and the Western Atlantic and here the British were happy to allow them dominance whilst the Japanese looked to China and East Asia in general as their stomping grounds. The alignment of the “Pacific Three” into a united, if unofficial, alliance took place in the immediate aftermath of the Short War. American President Horace Boies was something of an Anglophile and progressive enough to tolerate and even appreciate the Japanese. His domestic policies had focused on increase the rights of American workers and farmers, working with his Vice President Boies was a populist and his pro-union, progressive policies were well in line with both the “New Liberal” British Government of Sir Edward Grey (which encouraged government welfare and occasional interventionism) and the reformist Japanese Premiership of Okuma Shigenobu. Washington, Tokyo and London were all led by liberal reformists, all had aligned influences in the pacific and had much to gain from trade and cooperation. The Pacific Three, therefore, emerged naturally.

Not formalised in a treaty until 1900, the alliance mainly took the form of meetings between British Foreign Secretary David Lloyd-George, American Secretary of State Richard Olney and Japanese Foreign Minister Mutsu Munemitsu. The first priority was Spain and, of course, Cuba. The Cuban Revolution had led to an outpouring of sympathy in the US and worked directly in the interests of many American Imperialists such as Republican Governor of New York Teddy Roosevelt Jr, who called for an immediate intervention on humanitarian grounds. Boies was not much one for foreign intervention but nevertheless truly believed in the humanitarian case and thought it was in the interests of not just Cuba or the US but of the Americas in general to reduce Spanish and generally European influence. Boies had Olney approach his counterparts and suggest a joint intervention, offering the Philippines to the Japanese and Spain’s Atlantic holdings to the British. The Japanese immediately lept at the idea whilst the British were more concerned. In truth, the Spanish had little of value in the Atlantic and the British people were still celebrating from the last war, they didn’t need another. Nevertheless, Lloyd-George (with Grey’s blessing) agreed that the British would give full diplomatic support to the Americans and the Japanese and apply pressure to the Spanish so that the war might be brought to a rapid end.

Striking quickly, Boies declared war on June 19th 1896, declaring that the “languishing horror that is to be Cuban must be brought to a close and democracy must be brought to all the peoples of North America”. The Japanese entered the war on the 21st and immediately dispatched a squadron to Cuba. The Spanish, who had been struggling to put down just the Cubans alone, were immediately dismayed. It is hard to exaggerate the shambles that the Spanish government were in. Their King, Alfonso XII had died just a few months earlier and his infant son, Alfonso XIII was King. His regent and mother, Maria Christina, had barely had only been in power for a matter of weeks and still had not organised a united government. The ever-present threat of Carlist pretenders who insisted that Alfonso was a false King made the pressure at home even higher. She argued regularly with her ministers and the army and navy both operated largely as they pleased. The American and Japanese entry into the conflict only destroyed her authority even further.

The Queen Regent, though intelligent and popular, was doomed from the start.

At sea the Spanish were smashed in the Battle of Guantanamo and when the American Expeditionary Force landed in Cuba on the 8th of July they met astoundingly little resistance, many Spanish commanders surrendered outright whilst those who fought did so half heartedly at best. For months now they had been fighting a difficult war in tropical conditions against a guerrilla force that drained their supplies and stretched them thin. Thousands of Spaniards fell to disease and starvation as the ill prepared army suffered for months. Supplies were dwindling even before an American blockade and shelling of the coasts (where Spanish control was strongest) pushed Spanish commanders in land where not only did Cuban partisans make their lives hell but disease became even more rampant. Their fates were grim and within a matter of weeks the Spanish had any meaningful control of the island. Teddy Roosevelt Jr’s volunteer division, the Rough Riders, won a series of skirmishes with the Spanish and the Governor gained massive prominence from his role as a war hero, shutting up many of his critics who had dubbed him a “chickenhawk”. Roosevelt, a Republican, became increasingly close to the President over the next few years and though he clashed often with the VP, who he personally disliked, he became popular to both Democrats and Republicans. Before long, the Americans began to suffer from the same yellow fever that had so crippled the Spanish and hoped that a quick end to the war would reduce the casualties caused by sickness. In the Philippines, the Japanese fought a similar but smaller scale war. There was no local rebellion to exploit but, by the same token, barely any Spanish presence. The Spanish Pacific navy was, in all brutal honesty, a joke and was shattered by the IJN in a single battle in late June. The garrisons on the islands provided a somewhat firmer fight but just barely. Landing on the 25th of July, the Japanese had captured Manilla, Quezon and Caloocan had been captured by the IJA within a fortnight as their landings were aided by sea-bombardments. Not wishing to fight a bitter, long war, the Japanese simply shored up their positions in these three major cities and waited, content with the knowledge that a settlement would be reached.

Fighting, whilst brief, would echo the combat of the early stages of the Long War as Americans and Spanish deployed powerful modern weaponry against one another.

In Madrid, there was chaos. Their colonies had been seized with barely any resistance, their navy shattered on both sides of the globe and their men captured en masse. A last ditched effort was formed; almost all remaining ships and men were combined into a makeshift armada and put under the near absolute control of General Antero Rubin. They were to sail on the 10th of August, recapture Santiago de Cuba, the largest city in Eastern Cuba, and move West, dislodging the Americans as far as possible. The hope was not an outright victory (indeed it seemed the Philippines was abandoned almost entirely, with a hope that the Spanish might either be allowed to sell it to the Japanese, split it between the two powers or retain it in exchange for some other concession) but a moderated and more equal peace. In the end, this would not come to pass as the British condemnation of “Spanish barbarity” on August 3rd and a promise that “was a peace not reached, the navies and offices of the British Empire would engage in a total blockade of the Kingdom of Spain and all its overseas colonies”. The British ultimatum was a bluff, Grey did not want to waste his time or money when his struggles in parliament (at that time mainly attempts to expand the franchise to poorer men and improve the rights of British women) seemed so important. The Spanish brought it none the less and truthfully knew that they had little hope against two more youthful, powerful empires, nevermind three. The Treaty of Havana made Cuba an American protectorate whilst the Philippines (which the Japanese renamed Kapatiran, literally meaning “Brotherhood” in Tagalog, as part of negotiations with native leaders) became a semi-autonomous colony of the Japanese. The Spanish were dismayed and fell into a period of civil disobedience and political chaos, known as the Lost Decade. The Queen Regent was almost immediately deposed and replaced with a series of political and military regents and Prime Ministers who found themselves in increasing conflict with revolutionaries, hoping to restore the short lived Republic of the 1870s. In Japan and America however, the mood was bright. Japan’s meteoric rise seemed continuous and unstoppable, though there was a notable feeling of war-exhaustion on the rise and Tokyo was nervous that it was beginning to overexpand at a rate that was causing problems; minor rebellions in the Southern Philippines and the Jungles of Vietnam never became major crises but did shake governmental confidence. Most were happy however and the cultural boom continued, now spreading to America more freely as the Japanese were increasingly seen as friends and, in the words of one Democratic senator, “honorary whites”. Boies, whose policies had been controversial and divisive, though increasingly popular in the north and midwest, was hit with a massive spike of popularity and the democrats won big in the 1898 midterms. The newfound friendship between the Pacific Three chugged along, being formalised by the 1900 declaration of a new “League of Armed Neutrality” in response to the emergence of the European alliances of the Pact of...

Last edited:

So Ladies and Gentlemen which Chaos God do we sacrifice the major to if he doesn't post tomorrow ?

The Queen, of course!

Well there's always next time

Cant get me that easy! Don't worry though there'll be plenty of cockups I can be crucified over I'm sure.

Also guys thoughts? Opinions? Is the pacing good, is it still interesting, do we like the way the story is going, is it still plausible ect ect?

General thoughts, tips, predictions also good, I'd like to get a dialogue going on the direction, what places you want more detail on and what you guys want to see next?

General thoughts, tips, predictions also good, I'd like to get a dialogue going on the direction, what places you want more detail on and what you guys want to see next?

Also guys thoughts? Opinions? Is the pacing good, is it still interesting, do we like the way the story is going, is it still plausible ect ect?

General thoughts, tips, predictions also good, I'd like to get a dialogue going on the direction, what places you want more detail on and what you guys want to see next?

I'm sad because I can't think of any criticism

Anyways, it's going great so far, I don't really see any issues in it, and it's very interesting!

XIX - The Next Steps

Chapter Nineteen

The Next Steps

The Next Steps

Extract from: Strike Back – A History of the Second Entente

By: Jim Delaney, Published 2001 by Northouse Books

First Consul Boulanger’s transformation of France did not take place overnight. Whilst he was able to rapidly pass a series of constitutional amendments through the National Assembly it would take time for the Fourth French Republic to really take shape. When it did it was as a much more streamlined and efficient nation. Regional governments were abolished or streamlined, with France divided into 25 new “Provinces” each ruled over by a “Governor” appointed directly by the Consul. The National Assembly was replaced with a new Senate of 400 members, 150 of which were officers and representatives of the Military; 100 from the Army, 50 from the Navy. The rest were elected from France’s various provinces, 10 from each elected on a register that was limited exclusively to White, “True French” men. In order to be truly French one had to be born in the country or her colonies and have at least one parent and two grandparents also born in France. The franchise was, of course, limited to whites and Jews, Germans, Slavs and Britons were deliberately excluded. The Upper House of the French government was replaced with a 20 man council, half military and half civilian who were appointed by the Consul. In truth, the country had only the barest scraps of democracy left. Revanchist Republicans dominated in the first legislative election of the new Republic with a bare handful of Senators coming from the newly reformed Liberal Democrats and Imperial Socialists. A military reorganisation also began, France’s armies were retitled as “Legions” and it is not hard to see how very Roman in style the ideology was, even before it began to evolve. Boulanger was itching for a war but couldn’t find one France was ready to fight. Was he needed was a nice, quick, colonial affair but in Africa, France had only just been whipped by the British, in Asia she had no bases at all to expand from and the Americas were entirely under the watchful eye of Washington DC. So he sat and stewed and issues loud declarations of the might of France. Taxes went up as the army expanded, conscription brought in for all men between the ages of 18-30 for a period of no less than 5 years. The Government invested heavily in military industries and started construction on a series of new ships; battleships and screens mostly. His thought here was not to challenge the British but Germany; as France’s navy had been decimated at sea, their ability to challenge the Germans had been severely reduced. In recent years however the Germans had slowed on their naval construction, allowing the French an opportunity to catch up, one the Consul intended to seize. He would not be able to defeat France’s eastern foe alone however and in the last war Moscow had proven themselves not the fully competent ally France had hoped; they needed new blood.

France was again a military state but even she could not stand alone.

It was only under very specific circumstances that you could call the Austro-Hungarian Empire and its Emperor, Franz Josef “new blood”. The man was a stern traditionalist and despised the slow sweep of democracy and liberalism across Europe. Franz-Josef had, just a few years ago, joined the League of Three Emperors with the Russians and Germans and more recently forged a bond with the budding Italian Empire. By 1898 however, both the German and Italian Empires were becoming liberal, constitutional monarchies which disgusted Franz-Josef, what were they fighting for if not the defence of the old order? To make matters worse the Germans and Italians were both becoming increasingly disinterested in the Balkans and paid little heed to Austrian desires to carve up the remaining Ottoman territories. Despite this slow disentanglement, it came as a great surprise to the entire continent when the Austrians in May 1898, declared their alliance with the Germans and Italians void, instead signing onto the French-Russian Entente, signing two separate treaties. The first, the Treaty of the East was a deal between Vienna and St Petersberg, in public, the two simply pledged to help one another in the case of European war, however, a series of secret clauses were included. These extra clauses included plans and maps devised by a joint team of Austro-Hungarian and Russian generals, divvying up areas of influence in eastern Europe and assigning portions of the Balkans to each power as well as preliminary plans for a war with the Ottomans, should such an opportunity emerge. The second deal, the Treaty of the West, bound Austria and France together, it included a deal wherein the Austrians would purchase various pieces of French equipment and of course defend one another in the case of war – though with a deliberate “colonial exclusion clause” so that the Austrians would not see themselves up against Britain in any potential rerun of the Short war – and again signed a series of secret deals, this time outlining the two countries’ demands from Germany (Elass-Loraine to the French, Silesia to the Austrians with Bavaria as an independent Hapsburg Kingdom) and Italy (Venice to Austria, Sardinia to France).

The Germans and Italians were sent into a wild panic by this new alliance. Up until now the “Central Powers” just about outdid the strength of the Entente and whilst the Austrians were far from Europe’s premier fighting force they would be enough to tip the scales. Reaching out first to the British, the Germans received a series of vague and ultimately meaningless assurances of friendship. By now the Germans were certainly preferable to either the French or the Russians and no doubt Britain would intervene if either the sovereignty of Europe’s neutrals was compromised or if the continental balance of power was in danger of full collapse. Despite this, Britain already had a prosperous alliance with the Pacific Three and European entanglements threatened to once again shatter her splendid isolation, there would be no formal deal. The Dutch were the next stop; with Belgium increasingly falling into the French camp, the Dutch feared that French expansionism might see a return to the disasters of the Napoleonic wars and before long the Netherlands had tied themselves to the German mast.

Swedish style uniforms, with Caps for Officers and Tricorns for Regulars, became the Nordic standard.

The Scandinavians, only just having united into a single bloc some three years prior held a special Nordic Council in 1899 and agreed that, due to the threat of a once again expansionist Russia, they would collectively sign on to the German-Italian-Dutch Alliance. The Nordics also accelerated their plans for military integration, creating a unified high command, with integration completed in 1902. The Scandinavians also ordered a series of rifle trials to be held in the early months of 1900 with pitches from local companies as well as foreign ones such as Mauser, Enfield and Remington. The Enfield commission put forward their beloved Drum Magazine Rifle, the only semi-automatic candidate in a sea of bolt-actions. With its massive magazine size, solid accuracy, ease of use and incredible rate of fire, the DMR was held back by being more expensive to produce and more complex to repair. When it came to the trails, the DMRs outperformed all but the Mausers in both accuracy and reliability and, with their incredibly rapid rate of fire and ease of use, were adopted. The Scandinavians ordered a large shipment of 80,000 with more to come and sought out a licence so they could produce their own with some minor modifications that might better suit the winter environment. They received it the following year and by 1902 the armies of both Sweden-Norway and Denmark were being issued DMRs on mass.

A brief but rapid arms race began as the Germans attempted to match French naval build up and focused on the development of new artillery corps, hoping that their superior industry and technology might outdo the sheer numbers that the French, Austrian and Russian Empires could all bring to the table. The Scandinavians had done the same with their DMRs and the Italians began to expand both their border forts and the various defences they had scattered through the Alpine passes on the country’s eastern and western flanks. On either side of Europe, the Second Entente was hungry for blood and in the centre, what would come to be known as the “Central Bloc” or simply “the Bloc” stood firm, awaiting the inevitable. It was not until 1909 however…

Extract from: The Great Parliamentary Speeches 1800-1900

Sir Edward Grey, 16th May 1898

On: Irish Home Rule Bill (1898)

“This United Kingdom, extant now for some 97 years, was created at a time of discord, of conflict and chaos. The act of Union was a pragmatic deal and not, I am afraid to say, a truly stately one. When Albion and Eire were tied together it was perhaps not meant to be a permanent measure. The great Mister Pitt did not seek out a union for any reasons other than to prevent rebellion and ensure the integrity of the realm. His intentions were pure, his actions were just and indeed by becoming a United Kingdom we have grown as peoples but the future for Ireland lies not in the status quo. Must brothers be confined always to the same abode? No Mr Speaker, they must not! Why then do we not look forward, why do we not move forward not as paternalistic overlords of the Irish but as rationalistic allies? Home Rule is not the start of a slope or decline but a bold and permanent settlement. Unlike in the creation of this great United Kingdom, Mr Speaker we do not take this action for the benefits of today but for the fortunes of tomorrow, it is a patriotic and intelligent movement. It is only after many years of intense negotiation in this house and the other that I bring to you our most laudable proposal.

Sir Edward Grey, PM.

Mr Speaker I have led a government devoted to modernity and reform. When I call myself a New Liberal it is not simply so that I might escape the frankly towering shadow of my dear, late forebear, it is because I believe that as we approach the 20th century Britain must grow and change. We must have reform at home and in the empire and we must always be on guard that our democracy, which has always been both an ancient and modern institution, retains its traditions and its ability to look to the future.

The people of Ireland will have their own assembly organised in Dublin and the great provinces of Ulster, Munster, Leinster and Connacht will have their own. I know many of the right honourable gentlemen opposite were fearful for the rights of the godly Protestant but fear not Mr Speaker, no matter their faith, the people of Ireland will be represented. They will remain an integral part of this Kingdom of course and 40 of their current MPs will remain in this house. All will be satisfied, all will be represented and we shall have a representative and fair government for all the people of our blessed isles. Mr Speaker, I urge the House to vote in favour of the act, for the good of Ireland and the good of this United Kingdom.”

The Act passed the Commons on May 16th and the votes were as follows:

AYE: 483

Liberal Party: 270

Imperial Socialist Party: 97

Irish Parliamentary Party: 82

Conservative Party: 9

Independent Labour Party: 4

Others/Independents: 1

NAY: 252

Conservative Party: 170

Liberal Unionist Party: 81

Liberal Party: 1

The Act passed the House of Lords on May 29th and Ireland became an autonomous part of the United Kingdom on January 1st 1900.

AYE: 483

Liberal Party: 270

Imperial Socialist Party: 97

Irish Parliamentary Party: 82

Conservative Party: 9

Independent Labour Party: 4

Others/Independents: 1

NAY: 252

Conservative Party: 170

Liberal Unionist Party: 81

Liberal Party: 1

The Act passed the House of Lords on May 29th and Ireland became an autonomous part of the United Kingdom on January 1st 1900.

Last edited:

This update is a little massive so I nearly split it in two but I'm in Portugal atm which gives me lots of time and beautiful environment within which to write however also it means terrible internet which makes it hard to break up this gargantuan wall of text with pretty pictures so I apologise if its a little hard to read. Anyway I'm picking up the pace a bit so you enjoy, the internet is so awful it takes me minutes to load a page of just text so I probably won't be replying to comments for a while, awfully sorry. Please do keep giving feedback and thoughts however and I will one day have the chance to look back. Enjoy!

EDIT: I changed my mind, its just too big to neatly fit into one chapter so you can have two, all in one day! Whats bonkers is that these two updates alone, all written within the last day make up 10% of the entire TL so far :O Just proves what I can do when I put my mind to it, I hope the new detail and breadth is a positive and not making the TL dull or hard to read. Do let me know!

Whats bonkers is that these two updates alone, all written within the last day make up 10% of the entire TL so far :O Just proves what I can do when I put my mind to it, I hope the new detail and breadth is a positive and not making the TL dull or hard to read. Do let me know!

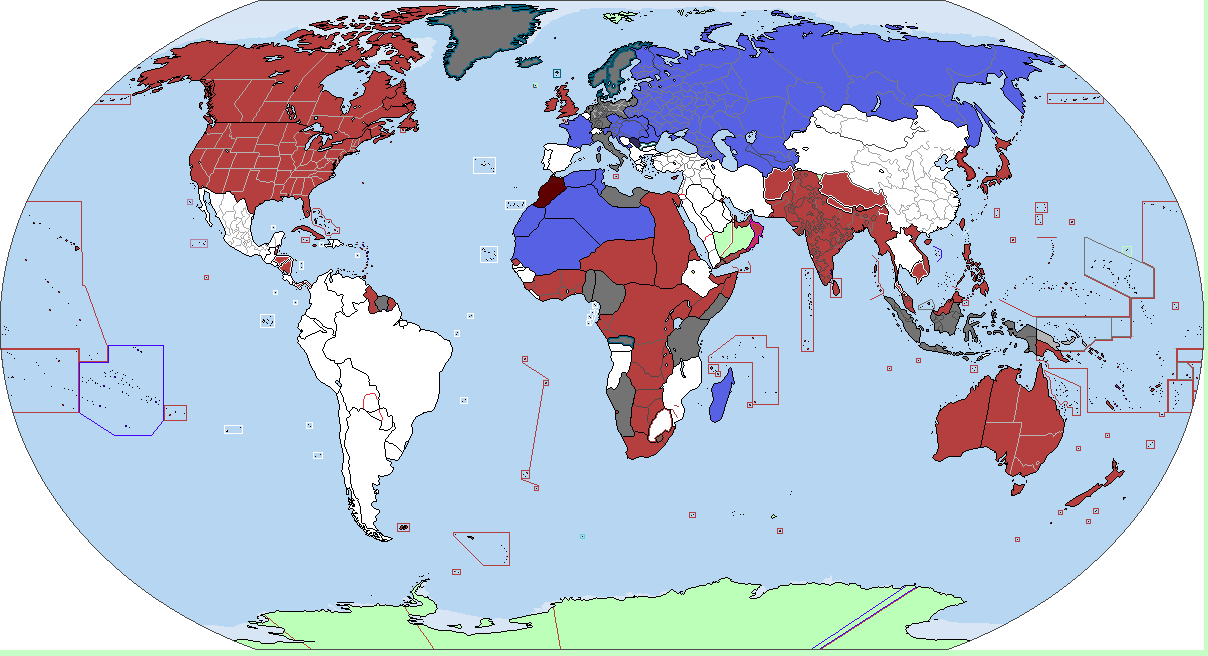

Oh and here's a map of the Alliance system as of 1900. British Red for the Pacific Three, French Blue for the Second Entente and German Grey for the Central Bloc.

EDIT: I changed my mind, its just too big to neatly fit into one chapter so you can have two, all in one day!

Oh and here's a map of the Alliance system as of 1900. British Red for the Pacific Three, French Blue for the Second Entente and German Grey for the Central Bloc.

Last edited:

XX - Freedom, Fraternity, Federation

Chapter Twenty

Freedom, Fraternity, Federation

Extract From: Freedom, Federation, Fraternity: A History of the UIC

By: Louis Penn

The Grey Government’s “Imperial Reform Bill 1899” built on a series of reforms they had made over the past years. With the franchise extended to all men above the age of 21, dominion status granted to Newfoundland and home rule finally achieved in Ireland, Grey had accomplished many of his sweeping legislative goals but three years into his tenure. When a private members Bill from Fabian MP Bertie Russell was introduced proposing “…the reform of the Dominions into Principalities with Governor Generals ceding their authority to permanent ‘Princes’, members of the Royal Family appointed by his Majesty the King to act as head of state and thus begin the process of Imperial Federation…” it received 200 votes in the Commons, with more than 40 defections each from the Liberal and Conservative parties. The event caused a minor stir in London and showed that many Fabian policies were not just popular across the Empire but within Parliament. Hoping to circumvent any further chances for the Imperial Socialists to steal the limelight and to perhaps win over a contingent of the Lib/ImpSoc swing vote, Sir Grey arranged a special meeting with His Majesty the King (and, as always, the Queen) and whilst Victor was somewhat confused by the idea, Queen Sybil was said to have adored it. The sovereign had never been much for politics and the weekly meetings between King and Prime Minister were often little more than a vague outline of the affairs of the week, a discussion on Imperial matters and an exchange of pleasantries. In 1894, Queen Sybil had started attending alongside her husband and either directly from her or via her encouragement of Victor, discussion and debate became more common. Therefore, with the approval of the Royal couple, the Prime Minister got to work.

The Queen was becoming increasingly present in the workings of British politics as her apolitical husband grew bored of his new duties.

Grey invited the Prime Ministers of Canada, Newfoundland, Cape, Westralia and Australasia to a special meeting of the bi-yearly Imperial Council in September 1898. From Newfoundland, the social democratic and Fabian-leaning People’s Party had won the Dominion’s first election in 1897 and thus were probably the most in favour, sending their PM Sir Edward Morris. Canada’s Liberal PM, David Mills, was adverse to surrendering any authority back to London and the only man at the conference explicitly opposed to Federation. His party, however, was increasingly in favour and the Canadian Imperial Socialists had been surging recently, worrying Mills enough that he would agree to moderate reform. The Conservative Prime Ministers of Australasia and Westralia, William Massey and John Leake were cynical, disliking the borderline social-democratic policies of Grey and, whilst they were not utterly opposed to Imperial Federation, they both feared Imperial Socialism’s influence. Meanwhile, Saul Solomon, Progressive Prime Minister of the Cape, had been drifting in a Fabian direction for many years and, his term in office lasting nearly 20 years, welcomed this new reform and planned to retire as soon as it was passed, seeing it as a good bookend to his time as premier. The group of men was a little hodge-podge but they were all, to less or greater extent, pro-Imperial Federation it seemed that Grey just might get the job done.

The negotiations were rushed as Grey wanted the appointment of Princes to be achieved on January 1st of 1900, not only an excellent symbolic moment for a renewal of the British Empire at the turn of a new century but coordinating that with the opening of the Irish Assembly would allow for a series of celebrations and a massive political win for the election he planned to hold a few months later. It is important to note that Ireland, whilst having its own Assembly, was simply a devolved part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland and thus would not receive its own king.

The bill passed surprisingly easily and despite not one but five Fabian speeches complaining that it had been their idea in the first place, there was near unanimity across the major parties in support of the idea. In the Dominions themselves, there was more debate; whilst the Canadians and Australasians passed their versions of the Bills rapidly, it took until September of 1899 for the Cape to finally get theirs past a large dissident group of the Cape Conservative Party. The Westralians dragged their feet until December but still got it through some three weeks before the planned coronation. With the various bills passed, the Dominions (whilst retaining their names and all other aspects of their relative constitutions) received their Princes.

The Prince of Canada was Duke Arthur of Connacht, King Victor’s Uncle who had been long tabbed as a candidate for Governor General and thus was a perfect choice. To Westralia the King’s younger Uncle, Duke Alfred of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha became King. As an outdoorsman and conservative, he was quite well received and soon took a liking to his desert home. The King’s brother, Prince George, became Prince of Australasia, reportedly he had desired Canada but nevertheless took well to his new posting, of all the Princes he brought with him the most pomp, building The Summer Palace just outside of Melbourne. A large piece of marble and gold, it was – at the time – arguably more grandiose and imposing than Buckingham Palace and Prince George went on to build up a true court with advisors, patrons and guests filling the hall of his lavish home. In Newfoundland, the most oft-forgotten of the Dominions which had gained its independence just three years prior, Princess Victoria, known to her friends and eventually her subjects as “Torri”, was appointed. Pretty, young and charismatic, the Newfies bonded almost immediately to their new sovereign and she fast became a national treasure. Finally, to the Cape went Princess Beatrice, Aunt of the King and reportedly Queen Victoria’s favourite daughter. Beatrice was quieter and subtler than her brothers and whilst there was some discontent in the Cape at receiving a Princess and not a Prince, she brought with her her on-again, off-again courter, Louis-Napoleon Bonaparte. Bonaparte and Beatrice had hoped to wed in the 1870s but nothing ever came of it, with the end of his Presidential ambitions in 1895 he returned to London and the romance was restarted. Beatrice had never wed and the couple, both growing older and still unmarried, eventually wed in 1903. Napoleon would remain in the Cape for ten years before his return to the forefront of politics.

On the 1st of January the three Princes, two Princesses, the new First Minister of Ireland John Redmond and all the ministers, lords and celebrities of the Empire were invited to London for a grand imperial celebration. Held over a week from New Year's Eve to the 6th, an “Imperial Fair” was put up in Hyde Park with each dominion and each of the home countries putting up stalls demonstrating their art, music, soldiers and food. Dignitaries came from across the globe as Kaiser Fredrich, President Boies and a host of Maharajas and Indian Princes flooded the streets of London. A series of parties, planned down to the dinner seating by the Queen, allowed for incredible nights of splendour and plenty. The turn of the century marked the apex of British confidence and pride, the Empire was happy, healthy and exceedingly wealthy.

This change is often lost in the sea of Imperial Reform that occurred in the late 19th and early 20th centuries but the appointment of the Princes effectively turned each of the Dominions into their own, self-contained monarchy, setting the stage for wholesale Federation.

Last edited:

I believe you have made a mistake as you say that the Australiasians both passes the bill rapidly and also drags its feet. I am guessing one of is the Westralia.

Good catch and ta, its meant to be the Westralians being awkward. I'll correct it now.

Its ramping up, now that the Liberals are on board there's very little opposition to Federation. The Unionists and Fabians are all in, the Conservatives are in favour of at least Imperial Preference and whilst they'd rather die than give colonials the vote, union with the white dominions still appeals to them. They are currently led by Salisbury again, however, and he's so terrified of reform that he'll oppose it on principle. The Liberals are split with the ruling New Liberal faction being pro-Federation and opposing Roseberry Classical Liberals being opposed, favouring the status quo.One Empire, One Emperor, One Federation!

A crown for every nation, eh? Some good updates here, especially in regards to the updating political situation. We know that something will happen with France by 1913 it seems. Looking at that map, the Ottoman Empire's probably going to want to join a camp soon enough.

Glad you're liking it and the next two updates are focused on American and then British political updates respectively before we move on to China, no comment on France but yeah the Sublime Porte are feeling a little left out in the cold and that big Austro-Russian bloc is looking awfully scary...

Got the next 3 updates already finished and I'll be posting them over the next 36 hours so give me thoughts and comments if you like.

Share: