Starting as a trickle of few families at the turn of the century, the number of Jewish immigrants fleeing to Britain from various parts of Europe had grown into a massive exodus by June 1902. Since the refugees were desperate and desolate enough to work with practically any wages, British workers in Greater London area felt that they were being pushed out. Once the number of immigrants exceeded 100 000, the British politicians felt obliged to act.

Repatriation was deemed as a potentially suitable solution, but the authorities were also eager to find a land where disparate Jews could settle permanently.

Since the Sinai Peninsula was exempted from land taxes, it was deemed as a suitable location during early discussions about the matter. But whereas Salisbury was cautious and Landsdowne preoccupied with the international Baghdad Railway negotiations, the local British representative, Lord Cromer, was initially at odds with his London masters.

Cromer was not

categorically opposed to the idea of Jews moving into Sinai. However, he had strong reservations about the length of the lease of territory, it's size, and whether it would be continous or broken up.[

1]

He also had to take the volatile mood of the "Arab street" into account. British rule in Egypt was still diplomatically challenged by the French, and the natives were restless.

Meanwhile Herzl and his associates were desperately seeking a refuge for Jews fleeing from Russia and Eastern Europe, and contacted the Egyptian government on their own. Their hopes were dampened when Boutros Pasha Ghali replied on February 22nd, 1903:

The Government of His Highness has taken note of your propositions for obtaining a charter for a "Jewish National Settlement Company" with a view to establish a Jewish Colony in the Sinai Peninsula. However, the Egyptian Government cannot, according to Imperial Firmans, for any reason or justification dispose of any part of the rights pertaining to sovereignty. Therefore, any idea aimed at obtaining agreements of this kind must be excluded.

The matter returned to political focus a few years later.

As it was, the factually-British-controlled-but-nominally-independent-Ottoman-vassal government of Egypt was involved in multiple border disputes with the Ottomans, both in Libya and in the Suez. As soon as they had secured their own rule, the new Ottoman government that had taken control of the state after the assassination of the previous Sultan reviewed their situation. France, Britain, Germany, Austria and Russia were all pressing in with railroad projects and gradual reduction of Ottoman sovereignty. The leaders of the Saviour Officer's movement,

Haliskar Zabitan, met this challenge by attempting to play the foreigners against one another.

At the same time they sought to uphold their historical claims to Egypt.

When the dust had settled after the first free Ottoman elections in a generation in 1906, the Ottoman representatives contacted the Egyptian government.[

2]

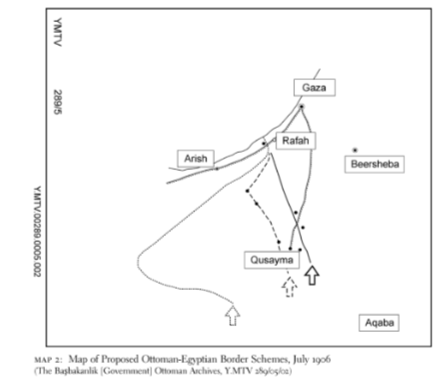

Their message was clear: there was no international treaty regarding the Ottoman-Egyptian border at the Sinai. The Ottoman view was that the Sinai Peninsula had been given to Egypt only for safe-keeping, and Egypt should now return it. The Sublime Porte wanted to establish the new border from Areesh to Suez and from Suez to Naqab-Aqaba. The Egyptian representatives turned down this proposal, and were also unwilling to split the area from Areesh to Ras Mohamed, with Egypt gaining the western part.

Both sides could only agree on the premise that the Firman of February 1841 had not solved the questions of the Gulf of Aqaba and the Sinai Peninsula.

The Ottoman state was firm on their right to send royal soldiers to Suez. Soon after they had agreed upon to intervene to the Balkans, the Powers were now facing a new challenge poised by the Ottomans further south.

1. As per OTL. Cromer was primarily interested in safeguarding the British control over Egypt, but was not as categorically opposed to Jewish plans to colonize the Sinai as he has been portrayed to be in many sources.

In TTL Herzl and rest of the movement do not squander their chances with the British so hastily, since they already have a better theoretical (but not actual) permission to settle people to Palestine from the Ottoman goverment than in OTL, and these negotiations with the Porte influence their general view of the situation.

2. The Ottomans started this border dispute in 1906 in OTL.