I wonder how the Swedish military planned to deal with the fallen - presumably with the German model by using field cemeteries.Well the real fun starts when the casualty reports start coming back.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The March of Time - 20th Century History

- Thread starter Karelian

- Start date

Threadmarks

View all 336 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 316: Feuds and fundamentalists Chapter 317: The Shammar-Saudi Struggle Chapter 318: Arabian Nights Chapter 319: The Gulf and the Globe Chapter 320: House of Cards, Reshuffled Chapter 321: Pearls of the Orient Chapter 322: A Pearl of Wisdom Chapter 323: "The ink of the scholar's pen is holier than the blood of a martyr."

Chapter 88: "Prudence and forbearance, comrades"

The course of events in Stockholm and other major cities of Sweden from September 1905 onwards were more or less directed by the interaction of two men: Herman Lindqvist and John Bernström.

Herman Lindqvist had taken part in the inaugural Congress of the LO (Landsorganisationen i Sverige, Swedish Trade Union Confederation) in 1898, and had been elected to the Secretariat as one of the founding members of the new organization. Later on he had succeeded Fredrik Sterky as the new chairman in 1900. He had also been active in SAP from the very beginning, and due the recent crisis Hjalmar Branting had just recently included him as a new member of the Party's executive committee. He had not risen to his position by mistake. Lindqvist was a calm, no-nonsense person. He had a reputation of being strictly factual and firm when holding speeches, while his capacities as an organizer were equally well-known.

Most importantly he was capable of showing great restraint when the situation seemed to demand it -and this was one of the reasons Branting had elevated him through the party ranks, and why he and Branting got along rather well. Both of them were committed to a long-term strategy, and Branting wanted to keep "hotheads" at bay by giving his full support for Lindqvist, who he had corrently identified as a capable leader and a strong potential ally. But as Branting would discover in the coming months, Lindqvist was nobody's stooge. As for his part, Lindqvist was determined to promote the agenda of LO, and was initially inclined to wait and see how the situation in Sweden would develop. He was a patient and cautious union leader, who had started his career as the chairman of LO by establishing a new strike and reserve fund as one of his first actions. The organization had then expanded rapidly under his tutelage, and the new-found strength of the movement had been clearly demonstrated in 1902, when LO and SAP had jointly organized demonstrations for universal suffrage, culminating to a two-day long strike.

This strike had also brought Lindqvist in contact with John Bernström, his chief adversary.

When the suffrage strike had been declared, Bernström had refused to give his workers any leave during the three strike days. All workers who participated to the strike regardless had then been immediately sacked, and all of their positions had been opened for new candidates. Effectively Bernström had forced most of his former workforce to beg their old jobs back. When they eventually were forced to accept his terms and re-enlist to his service, he chose not to rehire anyone seen as an organizer or agitator, but instead replaced over 200 workers by new unorganized workers or strikebreakers. Known henceforth as "The Separator" for his actions among labour circles, Bernström remained true to his reputation as a patriarchal and authoritarian employer. His actions were determined by his strong religiosity and hostility towards the socialist unions.

The fact that Hjalmar Branting and the Social Democratic Party had initiated the strike despite the opposition from some of the workers unions and Lindqvist himself was a fact that neither Bernström or Lindqvist had forgotten. As a result of the conflict Bernström had taken the initiative to reorganize and activate the VF, Sveriges verkstadsförening, as the national-level employers' organization, specifically organized to act as counterweight for LO. The VF and LO had crossed sabres again just a year later, during a nation-wide lockout in 1903. But after their second encounter, Lindqvist and Bernström had slowly but steadily developed quite a bit of mutual respect towards one another. They both knew that they represented completely competing visions for Swedish economy and society at large, and were certainly not friends. But Lindqvist had already realized that Bernström was not as adamantly anti-union as he publicly appearead: he had often been willing to participate to extensive negotiations behind closed doors, and to do compromises when he deemed them beneficial. Meanwhile Bernström had gradually learned to respect the growing strength Lindqvist had at his disposal, and to differentiate the more moderate figures like Lindqvist and Branting from the more militant factions of Swedish trade unions. By 1905 he silently appreciated the moderating influence SAP and LO leadership had to their supporters.

Branting, Bernström and Lindqvist all knew that the trade union base was ideologically much closer to the Young Socialists than SAP. Lindqvist was also troubled by the fact that the various syndicalist and anarchist elements present in the SUF were eager to mimic the violent and confrontational tactics used by the French syndicalists and Russian militants. So far the LO and the trade union leadership had acted as a restraining force, joining forces with moderate forces within SAP, mainly represented by Hjalmar Branting and his supporters. But due the outbreak of war it was no longer possible to agree with tactics and cooperation the syndicalists, who now neither wanted to work with LO or to endorse the demands for parliamentary reform through non-violent protests. As the first demonstrations were about to begin Branting, Lindqvist and Bernström had already held a brief and secret meeting to discuss their future options.

Herman Lindqvist had taken part in the inaugural Congress of the LO (Landsorganisationen i Sverige, Swedish Trade Union Confederation) in 1898, and had been elected to the Secretariat as one of the founding members of the new organization. Later on he had succeeded Fredrik Sterky as the new chairman in 1900. He had also been active in SAP from the very beginning, and due the recent crisis Hjalmar Branting had just recently included him as a new member of the Party's executive committee. He had not risen to his position by mistake. Lindqvist was a calm, no-nonsense person. He had a reputation of being strictly factual and firm when holding speeches, while his capacities as an organizer were equally well-known.

Most importantly he was capable of showing great restraint when the situation seemed to demand it -and this was one of the reasons Branting had elevated him through the party ranks, and why he and Branting got along rather well. Both of them were committed to a long-term strategy, and Branting wanted to keep "hotheads" at bay by giving his full support for Lindqvist, who he had corrently identified as a capable leader and a strong potential ally. But as Branting would discover in the coming months, Lindqvist was nobody's stooge. As for his part, Lindqvist was determined to promote the agenda of LO, and was initially inclined to wait and see how the situation in Sweden would develop. He was a patient and cautious union leader, who had started his career as the chairman of LO by establishing a new strike and reserve fund as one of his first actions. The organization had then expanded rapidly under his tutelage, and the new-found strength of the movement had been clearly demonstrated in 1902, when LO and SAP had jointly organized demonstrations for universal suffrage, culminating to a two-day long strike.

This strike had also brought Lindqvist in contact with John Bernström, his chief adversary.

When the suffrage strike had been declared, Bernström had refused to give his workers any leave during the three strike days. All workers who participated to the strike regardless had then been immediately sacked, and all of their positions had been opened for new candidates. Effectively Bernström had forced most of his former workforce to beg their old jobs back. When they eventually were forced to accept his terms and re-enlist to his service, he chose not to rehire anyone seen as an organizer or agitator, but instead replaced over 200 workers by new unorganized workers or strikebreakers. Known henceforth as "The Separator" for his actions among labour circles, Bernström remained true to his reputation as a patriarchal and authoritarian employer. His actions were determined by his strong religiosity and hostility towards the socialist unions.

The fact that Hjalmar Branting and the Social Democratic Party had initiated the strike despite the opposition from some of the workers unions and Lindqvist himself was a fact that neither Bernström or Lindqvist had forgotten. As a result of the conflict Bernström had taken the initiative to reorganize and activate the VF, Sveriges verkstadsförening, as the national-level employers' organization, specifically organized to act as counterweight for LO. The VF and LO had crossed sabres again just a year later, during a nation-wide lockout in 1903. But after their second encounter, Lindqvist and Bernström had slowly but steadily developed quite a bit of mutual respect towards one another. They both knew that they represented completely competing visions for Swedish economy and society at large, and were certainly not friends. But Lindqvist had already realized that Bernström was not as adamantly anti-union as he publicly appearead: he had often been willing to participate to extensive negotiations behind closed doors, and to do compromises when he deemed them beneficial. Meanwhile Bernström had gradually learned to respect the growing strength Lindqvist had at his disposal, and to differentiate the more moderate figures like Lindqvist and Branting from the more militant factions of Swedish trade unions. By 1905 he silently appreciated the moderating influence SAP and LO leadership had to their supporters.

Branting, Bernström and Lindqvist all knew that the trade union base was ideologically much closer to the Young Socialists than SAP. Lindqvist was also troubled by the fact that the various syndicalist and anarchist elements present in the SUF were eager to mimic the violent and confrontational tactics used by the French syndicalists and Russian militants. So far the LO and the trade union leadership had acted as a restraining force, joining forces with moderate forces within SAP, mainly represented by Hjalmar Branting and his supporters. But due the outbreak of war it was no longer possible to agree with tactics and cooperation the syndicalists, who now neither wanted to work with LO or to endorse the demands for parliamentary reform through non-violent protests. As the first demonstrations were about to begin Branting, Lindqvist and Bernström had already held a brief and secret meeting to discuss their future options.

Chapter 89: We must be violently pacifistic!

Fratricide, Part V: What Are We Fighting For

"Det är bättre av en hämnare nås

än till intet se åren förrinna,

det är bättre att hela vårt folk förgås

och gårdar och städer brinna.

Det är stoltare våga sitt tärningskast,

än tyna med slocknande låge.

Det är skönare lyss till en sträng, som brast,

än att aldrig spänna en båge."

Exerpt from "Åkallan Och Löfte"

The war in Scandinavia did not appear out of the blue. It had been waged in literature long before the first shots had been fired in real life. Poetry, plays, novels and newspaper articles dealing with the idea and expectations of a new war in the North were present in both sides of Swedish society, and while others abhorred the idea, others longed and hoped for it. The pacifists emphasized the massive destructive power of modern weapons, and predicted that a new war would turn into senseless mass slaughter that would display the morbid degeneration and bloodlust of Swedish ruling elites.

The right-wing nationalists focused on the idea of war as a national great sacrifice, a test of manhood, and a necessary moment of revival of the past Swedish greatness. Gone were the days of the miserable old and neutral passivity, cowardice and degeneration, as the return of the glorious past when Sweden had been a proud warring nation was now finally at hand.

Among the peasant population the old traditional view of war as just another God-given calamity that had to be endured at least partially explains the fatalistic mood among the Swedish agrarian population in autumn 1905.

When the war begun, the first movement to fully mobilize against it was the SFSF (Svenska Freds- och Skiljedomsföreningen, Swedish Society for Peace and Arbitration). It was a small, noisy and well-established liberal organization, firmly rooted in Western European classical liberal ideas of progress. Mocked as fredsfåren by their political opponents, the originally liberal organization that had been in existence for over 20 years had by 1905 gained a markedly left-wing orientation, with many leading figures of the movement being also notable Social Democrats. But as a whole the members of the movement were a mixed lot. In addition to socialist anti-militarists or - in the case of SUF - outright defense nihilists, SFSF also had feminist pacifists (mainly supporters of Ellen Key and her theories) and Christian pacifist supporters.

Many Swedish liberals, who were traditionally not opposed to armed neutrality per se, were now joining the ranks of the movement to oppose the conflict. Initially even this movement was unable to act in a coordinated fashion against the war. This was mainly because left-wing supporters were squabbling over a key doctrinal question: could militarism be opposed as a phenomenon independent from class struggle and class society? The most anti-militaristic members of SFSF were advocating violent resistance to militaristic society, and claimed that nothing less than a revolution would be required to completely uproot the old values and oppressive structures that enabled militarism to prosper and fuction in Swedish society. Meanwhile the Social Democratic mainstream pointed out that one couldn't exactly call violent anti-militarism pacifism in the traditional sense of the word. Thus the anti-war opposition was much slower to start any kind of effective resistance to the war than it had been previously predicted, and during the first weeks of the conflict the Swedish government hoped that they could be able to ride out the storm.

"Det är bättre av en hämnare nås

än till intet se åren förrinna,

det är bättre att hela vårt folk förgås

och gårdar och städer brinna.

Det är stoltare våga sitt tärningskast,

än tyna med slocknande låge.

Det är skönare lyss till en sträng, som brast,

än att aldrig spänna en båge."

Exerpt from "Åkallan Och Löfte"

The war in Scandinavia did not appear out of the blue. It had been waged in literature long before the first shots had been fired in real life. Poetry, plays, novels and newspaper articles dealing with the idea and expectations of a new war in the North were present in both sides of Swedish society, and while others abhorred the idea, others longed and hoped for it. The pacifists emphasized the massive destructive power of modern weapons, and predicted that a new war would turn into senseless mass slaughter that would display the morbid degeneration and bloodlust of Swedish ruling elites.

The right-wing nationalists focused on the idea of war as a national great sacrifice, a test of manhood, and a necessary moment of revival of the past Swedish greatness. Gone were the days of the miserable old and neutral passivity, cowardice and degeneration, as the return of the glorious past when Sweden had been a proud warring nation was now finally at hand.

Among the peasant population the old traditional view of war as just another God-given calamity that had to be endured at least partially explains the fatalistic mood among the Swedish agrarian population in autumn 1905.

When the war begun, the first movement to fully mobilize against it was the SFSF (Svenska Freds- och Skiljedomsföreningen, Swedish Society for Peace and Arbitration). It was a small, noisy and well-established liberal organization, firmly rooted in Western European classical liberal ideas of progress. Mocked as fredsfåren by their political opponents, the originally liberal organization that had been in existence for over 20 years had by 1905 gained a markedly left-wing orientation, with many leading figures of the movement being also notable Social Democrats. But as a whole the members of the movement were a mixed lot. In addition to socialist anti-militarists or - in the case of SUF - outright defense nihilists, SFSF also had feminist pacifists (mainly supporters of Ellen Key and her theories) and Christian pacifist supporters.

Many Swedish liberals, who were traditionally not opposed to armed neutrality per se, were now joining the ranks of the movement to oppose the conflict. Initially even this movement was unable to act in a coordinated fashion against the war. This was mainly because left-wing supporters were squabbling over a key doctrinal question: could militarism be opposed as a phenomenon independent from class struggle and class society? The most anti-militaristic members of SFSF were advocating violent resistance to militaristic society, and claimed that nothing less than a revolution would be required to completely uproot the old values and oppressive structures that enabled militarism to prosper and fuction in Swedish society. Meanwhile the Social Democratic mainstream pointed out that one couldn't exactly call violent anti-militarism pacifism in the traditional sense of the word. Thus the anti-war opposition was much slower to start any kind of effective resistance to the war than it had been previously predicted, and during the first weeks of the conflict the Swedish government hoped that they could be able to ride out the storm.

Last edited:

One thing that'll be fascinating is that if this northern conflict doesn't develop into the Great War, it may well provide very different lessons for foreign observers than the Second Boer War did. I doubt British and French staff officers will be reporting back about the need for cavalry and mobility in a modern war....

One thing that'll be fascinating is that if this northern conflict doesn't develop into the Great War, it may well provide very different lessons for foreign observers than the Second Boer War did. I doubt British and French staff officers will be reporting back about the need for cavalry and mobility in a modern war....

Well Norway (even relatively flat eastern Norway where the action is taking place) has never been good cavalry country. Terrain is too hilly/craggy and densely forested which I'm sure most cavalry officers will use in their own defense. But yes, all that is missing is submachineguns, handgrenades, infantry mortars and landmines and warfare will never be the same.

Too bad it's 1905. A Norwegian, Nils Waltersen Aasen patented the first modern handgrenade in 1906 at a British patent office. Might have been ready before that though. Thing was definitly developed with a Swedish war in mind although he was never able to convince the norwegians to buy it.

Last edited:

Chapter 90: " You're old enough to kill but not for votin' "

Stubborn resistance against universal suffrage had formed the domestic political background to the political mobilization of the Swedish working class.

One of the arguments for voting that was used during the strikes of 1903 had been the new conscription system, introduced in the previous year. A popular argument questioned whether it was reasonable to expect young men to risk their lives for their country without granting them full civil rights. The bicameral system established in 1865 was far from a democratic system: during the first elections only 9% of male population had been eglible to vote for the second chamber, while the first chamber had been in effect exclusively reserved for the landed nobility. While the second chamber suffrage had been gradually expanded to a point where roughly half of the male population was eglible to vote for the second chamber, the power and prestige of the first chamber had concentrated to a small elite, which sometimes had to gain as few as 100 voices to become elected. In this situation, the "En man - ett gevär - en röst!" (One man - one rifle - one vote!)-slogan of the suffrage activists was certainly an effective rallying cry.

By what right did "the hardened adult world" force the young men to spend a whole year in uniform? And even more relevant, were the elder statesmen entitled to force the new generation to the battlefields against their former countrymen, who were not threatening their safety in any way?

This connection between military service and suffrage reform had been a hotly debated topic in the first chamber and court circles. But plans to introduce universal male suffrage for the first chamber were still nothing but early committee drafts when the secession crisis begun, and many Swedish soldiers conscripted to fight for king and country had had no chance to vote for the government that ordered them to fight. The liberal and social democratic demands for constitutional reform had so far been stopped to the fact that many first chamber notable politicians opposed the very principle of parliamentarism.

The fact that universal and equal suffrage for municipal elections would destroy the old social order in the Swedish countryside was also a significant factor, and attempts to reach a compromise solutions had all been stopped to a key issue - the first chamber had been unwilling to give up the privileged voting system, preferring to maintain their old power base as "a guarantee against rapid social changes" in a situation where the workers and landless population gained the right to vote.

But by now it was already too late for easy compromises. The battle lines had been drawn, and neither side would back down without a fight.

One of the arguments for voting that was used during the strikes of 1903 had been the new conscription system, introduced in the previous year. A popular argument questioned whether it was reasonable to expect young men to risk their lives for their country without granting them full civil rights. The bicameral system established in 1865 was far from a democratic system: during the first elections only 9% of male population had been eglible to vote for the second chamber, while the first chamber had been in effect exclusively reserved for the landed nobility. While the second chamber suffrage had been gradually expanded to a point where roughly half of the male population was eglible to vote for the second chamber, the power and prestige of the first chamber had concentrated to a small elite, which sometimes had to gain as few as 100 voices to become elected. In this situation, the "En man - ett gevär - en röst!" (One man - one rifle - one vote!)-slogan of the suffrage activists was certainly an effective rallying cry.

By what right did "the hardened adult world" force the young men to spend a whole year in uniform? And even more relevant, were the elder statesmen entitled to force the new generation to the battlefields against their former countrymen, who were not threatening their safety in any way?

This connection between military service and suffrage reform had been a hotly debated topic in the first chamber and court circles. But plans to introduce universal male suffrage for the first chamber were still nothing but early committee drafts when the secession crisis begun, and many Swedish soldiers conscripted to fight for king and country had had no chance to vote for the government that ordered them to fight. The liberal and social democratic demands for constitutional reform had so far been stopped to the fact that many first chamber notable politicians opposed the very principle of parliamentarism.

The fact that universal and equal suffrage for municipal elections would destroy the old social order in the Swedish countryside was also a significant factor, and attempts to reach a compromise solutions had all been stopped to a key issue - the first chamber had been unwilling to give up the privileged voting system, preferring to maintain their old power base as "a guarantee against rapid social changes" in a situation where the workers and landless population gained the right to vote.

But by now it was already too late for easy compromises. The battle lines had been drawn, and neither side would back down without a fight.

Chapter 91: "The prevailing situation, of course, is only the beginning of something more."

"As recent experiences have shown, the ruling classes and their political bodies will not listen to any other language than that of brute force, the people can be fooled to cast aside their innate desire for peace, and that the parliamentary struggle has been insufficient to prevent this disaster, this calls for preparations to be made for the organization of an extra-parliamentary mass action, effective immediately" read the first paragraph of a leaflet that the Sveriges Ungsocialistiska Förbund (SUF) planned to print with hundreds of thousands of copies. Despite the fact that the Swedish police confiscated their printing press equipment soon afterwards in a swift crackdown, the reprinted copies of the SUF ”Krig mot kriget!”(To war against war!)-pamphlet continued to spread from hand to hand among the Swedish population.

The document, aimed primarily for soldiers, LO and SAP members, stated that first act of resistance should be a well-organized general strike. The manifesto also concluded that if the ruling classes chose to resist the demands for an immediate ceasefire, the general strike "may then have to be escalated over into a struggle of far more acute character." As “the Swedish government, in violation of the policy of neutrality, had now thrown the country into a genocidal war”, SUF manifesto stated that the logical conclusion was that "obviously all obligations of loyalty towards such a regime have ceased to exist."

This strike slogan found a great resonance among the workers. LO management was soon besieged with statements from local trade union and demonstration meetings, calling for an immediate general strike. Lindqvist, however, did everything he could to slow down the movement of the masses, and warned incessantly about the dangers of acting too early, and in an unorganized fashion. But his was a lone voice, shouting in vain to a rising wind.

On October the LO General Council held a meeting to consider the situation. Lindqvist, brief as always, stated that the Secretariat now found it opportune to reconsider the earlier position regarding the possiblity of strike action. LO had initially been required to stay outside and threatened by government action, he explained, but it was now feared that the SAP party leadership would soon have succumb to the demands of the masses and initiate the strike, which LO would have to lead and organize in any case.

The union leaders present were all well aware of the mood among the workers, and their impatient calls for a general strike, which, as Mr Lindqvist undramatically stated "given the current situation, of course, is only the beginning of something more." Everywhere in the country the workers themselves were already announcing local strikes and walkouts without notifying local LO organizers. The situation in Malmö was especially described as “absolutely hopeless”, as far as regaining control of the situation was concerned. But the majority of Representatives, mostly Nils Persson and steward of Commerce J. A. Lundgren, both from Malmö, criticized the Secretariat that it was failing to do its duty of leading the workers by the procastrination caused by Lindqvist. The critics stated that it was obvious that the collective connection of the trade unions and SAP had by now lost the earlier restraining effect it had had to SAP and the industrial workers in general. The time to act was now, whether the LO leadership liked it or not.

It was all well and good, even noble, that the LO leadership had wanted to avoid an open fight, CE Smith, one of the most reliable on the extreme right wing of the party leadership, stated. But he continued by asking what the LO leadership was going to do now, when a general strike was about to begin regardless of will of the LO? "Will you gentlemen then just sit with folded arms and let others take the lead?"

The document, aimed primarily for soldiers, LO and SAP members, stated that first act of resistance should be a well-organized general strike. The manifesto also concluded that if the ruling classes chose to resist the demands for an immediate ceasefire, the general strike "may then have to be escalated over into a struggle of far more acute character." As “the Swedish government, in violation of the policy of neutrality, had now thrown the country into a genocidal war”, SUF manifesto stated that the logical conclusion was that "obviously all obligations of loyalty towards such a regime have ceased to exist."

This strike slogan found a great resonance among the workers. LO management was soon besieged with statements from local trade union and demonstration meetings, calling for an immediate general strike. Lindqvist, however, did everything he could to slow down the movement of the masses, and warned incessantly about the dangers of acting too early, and in an unorganized fashion. But his was a lone voice, shouting in vain to a rising wind.

On October the LO General Council held a meeting to consider the situation. Lindqvist, brief as always, stated that the Secretariat now found it opportune to reconsider the earlier position regarding the possiblity of strike action. LO had initially been required to stay outside and threatened by government action, he explained, but it was now feared that the SAP party leadership would soon have succumb to the demands of the masses and initiate the strike, which LO would have to lead and organize in any case.

The union leaders present were all well aware of the mood among the workers, and their impatient calls for a general strike, which, as Mr Lindqvist undramatically stated "given the current situation, of course, is only the beginning of something more." Everywhere in the country the workers themselves were already announcing local strikes and walkouts without notifying local LO organizers. The situation in Malmö was especially described as “absolutely hopeless”, as far as regaining control of the situation was concerned. But the majority of Representatives, mostly Nils Persson and steward of Commerce J. A. Lundgren, both from Malmö, criticized the Secretariat that it was failing to do its duty of leading the workers by the procastrination caused by Lindqvist. The critics stated that it was obvious that the collective connection of the trade unions and SAP had by now lost the earlier restraining effect it had had to SAP and the industrial workers in general. The time to act was now, whether the LO leadership liked it or not.

It was all well and good, even noble, that the LO leadership had wanted to avoid an open fight, CE Smith, one of the most reliable on the extreme right wing of the party leadership, stated. But he continued by asking what the LO leadership was going to do now, when a general strike was about to begin regardless of will of the LO? "Will you gentlemen then just sit with folded arms and let others take the lead?"

Chapter 92: Carolean discipline

Art 61

Ingen frisk och hälsosam Soldat, skall varken i tågande vara från dess Estandar eller Fana, eller då Lägret satt är låta sig finna ifrån Armeén utom vakterna, utan pass och riktigt besked av dess Överste eller andre Officerare, vid livsstraff tillgörandes.

The Swedish Army went to war with a tried-and-true system of military discipline: the Regimental Martial Law was based on articles of war created by Gustav II Adolf in 1621! According to this harsh and effective system, each Swedish regiment had been ever since obliged by law to exercise judicial power over all soldiers who violated the military penal codes, and to enforce the judiciary punishment in criminal cases. When conscription was introduced in 1883, the law was slightly revised to appease the agrarian population, and flogging was removed from the list of acceptable punishments in 1882. Other than that the martial jurisdiction remained virtually intact, and firmly in military hands as the penal code for armed forces and war tribunals. This was especially troubling for many Swedish politicians, since all the other forms of Swedish archaic special jurisdictions (universities, the mining, urban, etc.) had been long since merged into national law and standardized by 1905.

The fact that the old harsh penal code remained in force despite the transition to the new universal conscription system created a lot of resentment. A motion to the Second Chamber, brought forward in 1901 by a leading Liberal politician, Karl Staaff, had sought to achieve several revision to the laws of war. The main aim of the motion had been to ensure the compliance with the general Swedish law in the armed forces, especially considering the treatment of young recruits. After several such motions had been presented for the abolition of the old legal system, the government had finally appointed a bicameral committee in the same year to deal with the matter. As the First Chamber actively opposed all attempts to alter the status quo or threaten the special legal position of the armed forces, the Committee had been unable to achieve any progress by 1905.

And thus the old system was still in use by the time the Swedish armies crossed the Norwegian border. The regimental court was assembled to deal with all cases. It was led by the regimental commander, although he in fact often delegated his judicial power to a major, who acted as the chairman instead. Two lieutenants, a first degree NCO, and a legally trained auditor had also be present. The regimental Provost Sergeant served as a prosecutor in most regiments. All allotted soldiers were under the jurisdiction of the regimental court-martial, usually for both military and civilian targets, both in wartime and peacetime. The penalties were enforced by the company commander. The process was simple, the penal code dragonian, and totally out of the control of Swedish civilian leaders.

Last edited:

Just to post to say that I'm really enjoying this arc of the story, but I don't remotely know enough about the period to have any useful insight. Keep it up, though, it's a good read.

Chapter 93: The Bridge

“The world has never seen a more remarkable strike: Its program has a scope way beyond the call for peace! It embraces the full range of accusations against an unjust social system, and simultaneously holds true to all claims and demands from the simple wage claims, up to the call for a new democratic and just state order. As a flash of lighting this revolutionary program shines its glare across the whole society. It represents the rights, power and will of the working class! The social and political requirements are one and indivisible. It is a solid revolt against persecution, torment and other atrocities committed in the name of this mad war!"

Spartacus (C. N. Carleson), 1905.

15th of October, 1905, Thursday.

During the midday the Stockholm workers stopped their work. Soon people from all over the city marched towards the Northern Railway Square, the location of the Folkets hus, the center of labor and SD activity in the city. A hour later the square was packed. The gathering crowds sang songs, chanted anti-war slogans, and cheered ethusiastically to speeches held from the balcony of the People's House. Soon the mass demonstration was moving closer to the heart of the city. This demonstrations had gathered more or less spontaneously, as a part of a wider unrest and mass demonstrations that had been taking place all across the country during the last few days. So far the local military garrisons had performed poorly when they had been tasked to deal with protesters. In Västerås, a group of soldiers in uniform had gathered to a solidarity demonstration in support of the striking workers.

When police had been sent to arrest the soldiers, large crowds of striking workers had rushed to the scene, starting a local riot. In Boden, Falun, Ostersund, Skeppsholmen and many other garrison areas there had been reports of small-scale mutinies. Soldier demonstrations and refusals to leave the training camps to the front had occurred in almost every regiment. A single officer had already been shot during a live-fire exercise in Boden, and the perpetrator could not be identified. There were even instances where the soldiers had outright deserted from their guardposts.

The government forces had not been idly following this rising tide of public unrest. The first death penalties sentenced according the Regimental Laws had already been dealt with, and after the first public executions the discipline of the Swedish reservist formations was seemingly improved. A number of security measures had already been instituted at Stockholm as well. The garrison troops present at Stockholm were now drawn from regiments drafted from the countryside, as farm boys from Skåne were regarded as more reliable than local unruly worker conscripts.

Överkommendant of Stockholm had strictly forbidden the newly arrived conscripts and servicemen from attending “socialist meetings,” or any kind of public meetings at all. They had been kept tightly on their garrison quarters, only to be hastily marched to their new posts with orders to wait for further instructions.

Thus the crowd gathering to Stockholm was met by a force consisting of commissioned police personel, reinforced with military units of the Stockholm garrison. The North Bridge, the only way to the island of Helgeandsholmen where the parliament building was located, was closed and under a strong guard. Lines of policemen were placed in front of the windows of the parliament house and adjacent business edifices.

On this cloudy and chilly October day, a half company of infantry conscripts, fresh from the training centers of Kungl. Södra skånska infanteriregementet from southern Sweden, nervously waited orders, cordoning the North Bridge with fixed bayonets. Another half company was stationed at the front of the main telegraph office.

The agitators among the gathering masses of people publicly called for immediate ceasefire, suffrage reform, eight-hour working day, amnesty for political prisoners and especially for soldiers and workers who participated in the demonstrations against the war.

”Krig mot kriget!”

”Rättvisa åt Norge!"

"Fred med Norge!”

”Krig mot kriget!”

The crowd roared the anti-war chants louder and louder, and kept moving closer, with the boldest demonstrators slowly and calmly walking towards the North Bridge in tight columns, the bannermen proudly waving the red flags of SAP, SOF and LO. These young men and women were urged on by local firebrands and demagogues, and were physically pushed ahead by the mass of demonstrators behind them. As they walked steadily closer, the police lines guarding the northern entrance of the bridge were suddenly withdrawn, as were the soldiers. The crowd hesitated for a moment.

Then there was a loud clarion call, and the formations of mounted police officers rode to the square, slowly at first, sabres drawn and rawhide whips at the ready. They almost immediately gathered a bit of speed and rode forward to a charge.

The mounted policemen charged to the panicking crowd, beating the fleeing demonstrators with whips and sabre hilts as the horses kicked and trambled. Chaos ensued. Rioting workers hurled stones and bottles. A police chain of Strömgatan gave way, and the workers stormed the square that had been cordoned off. The mounted police quickly regrouped, and charged again, three times in total.

People screamed, as many were trampled down and severely injured when the crowds fled in panic. Many demonstrators, men and women alike, were wounded. The demonstrators rallied at the Railway Square. The soldiers guarding the Parliament and the royal castle were left standing idly at the North Bridge, with panic in their eyes, closely watched by their equally nervous officers.

Everyone present realized that this time the police had been able to do their job, but just barely. The soldiers knew their orders all too well. If the crowd returned, their task was to stop it, by any means necessary. By nightfall, as per orders of the the Överkommendant of Stockholm, barbed wire obstacles closed the Northern Bridge and other entrances to the Gamla Stan government district.

And at the cover of the night, a small group of soldiers laboured at the second small tower of the Bonde Palace. The uppermost windows at the attic were dark and narrow, the stairs had been almost hopeless, and the damn thing weighted over 115kg. But orders were orders, and ultimately they managed to finish their work. Resting on an improvised sandbag mount, a single Palmcrantz 12,17x42R Kulspruta m/1875 multi-barrel machine gun was now in position to cover the Vasa Bridge. The crew of this contraption consisted of soldiers hand-picked by the garrison commanders, and deemed calm and reliable enough to do their duty if need be.

Last edited:

Which was the main reason Swedish army only bought a limited amount, mainly for testing. Meanwhile the Norwegians waited just a bit longer, and ended up with an air-cooled, belt-fed weapon.You sometimes forget how fast small arms development progressed during the time period. Nordenfeld guns would seem extremely ourdated at the time but was a barely 30 year old design.

Chapter 94: Karl Staaff and the Liberala samlingspartiet

"A leader should be the standard-bearer. He should be the one to take the lead and withstand criticism, not least from different schools of thought within the party, and thus serve as a spitting box. It is in the interest of hygiene that as many as possible spit tidily in one place instead of everywhere."

Few men could boast that the business elite of Sweden had ordered custom-made ashtrays with their potrait on them, just to be able to symbolically stomp their cigarettes to the face of their worst enemy. Karl Staaff could.

Officers spat to his feet in the street. In daily letters, telegrams and nightly phone calls, he was repeatedly warned of the dire consequences of inciting the people against the king. And yet Karl Staaff seemed to care little of the opinions of others, as usual. Staaff was a loner, who preferred to develop his policies and tactics in solitude. Sixten von Friesen, the previous leader of the Swedish Liberal party, Liberala samlingspartiet, had been soundly suprised by his latest action. Staaff had inherited the party from the previous leader, and soon his position as the chairman was unchallenged. Staaff demanded dedicated party discipline, and negotiated in the name of the whole party without consulting his colleagues. His close aide despaired to his friend in private:

“Staaff never makes a major decision on any issue of note until he has thoroughly considered it privately. There he considers, makes drafts, debates with himself, for and against, examines the matter from all sides, and then comes out with his mind all set up. Resistance is futile. All feedback or proposals are rejected, as Staaff merely states that he has arealdy himself examined them and responded to them."

As a result of his personal working methods, Staaff was hopelessly out of touch of the daily political realities of Swedish voters and the rank and file of his own party. His plans to lead the Liberals to a role of a stateholder party as a respectable, modernizing, center-left coalition were as grand as they were unrealistic, but Staaff himself firmly believed that history was on his side. And the workers did like him: as a lawyer by profession, he had written guide for union organizing legisrature. This small booklet, “Verdandiskriften Församlingsrätten” was called "Meeting Catechism" among LO members, as it was often used by working-class agitators when they faced police harassment. Staaff and his Liberals had also often foiled the First Chamber conservative attempts of pushing through anti-union legislation.

Despite his firm advocacy and promotion of democracy and equality for all citizens, Staaff had always felt that local-level municipal elections were not important enough to a determined lobbying of universal suffrage. He had chosen to focus his efforts on pressuring the First Chamber for a total electoral reform instead of gradual changes. His stubborn style and lack of finesse had managed to alienate most of his potential allies, and by the time of the Secession Crisis, it seemed that the electoral reform law draft he had been working on since 1902 was about to fail as well.

He had also directly challenged the Swedish elite and especially the military high command by publicly inquiring what kind of military plans the High Command actually had, and by openly expressing his distrust to the military in their capacity of investigating their own funds. Here he openly challenged the traditional view of the officer corps as sworn servants of the Crown. When Staaff kept on insisting that the military should be an authority among others, and therefore subject to parliamentary scrutiny and transparency, he thus took on both the military high command and the established power structures of the Swedish monarchy itself.

Despited by the revolutionary leftists and loathed by conservative elites and the military brass because of his convictions and views, Mr. Staaff and his party were nevertheless a critical part of the domestic politics of Sweden. No one was going to be able to solve the crisis at hand without taking him and his party into account.

Last edited:

It's the final month of upper elementary school, so spare time is a luxury I don't have. Until 3rd of June, after that it's all fine and dandy until August.Got a feeling that the pause means we'll be moving back to the front soon. Karelian needs to get his ToEs in full order

And yes, the frontline situation will an another update, as well as the war at sea.

Chapter 95: Swedish order of Battle, 1905

The Swedish Order of Battle, 1905

Första Arméfördelningen (1st Division)

Arméfördelningschef (Divisional Commander): Gen.Major Axel Fredrik von Matern

Stabschef (Chief of Staff): Major Alfred Henrik de Maré

Generalstabsofficer (General Staff Officer): Kapten Johan Gustaf Nanekhoff

Adjutants: Frih. Löjtn. Nils Otto Palmstierna and Frih. Löjtn. Kjell Rutger Carl Bennet

Forces: K. Karlskrona Grenad. Reg., K. Kronobergs Reg., K. Hallands Reg., K. Norra Skånska Infant.-Reg., K. Södra Skånska Infant. Reg., K. Skånska Husar-Reg., K. Skånska Dragon-Reg., Kronprinsens Husar-Reg., K. Vendes Artill. Reg., K. Skånska Träng-Kåren.

Andra Arméfördelningen (2nd Division)

Arméfördelningschef (Divisional Commander):Gen.-Major Gustaf Fredrik Oscar Uggla

Stabschef: Major Johan Axel Fabian Carleson

Generalstabsofficer: Kapten Carl Gustaf Valdemar Hammarskjöld

Adjutants: Löjtn. Carl Pehr Pontul Renterswärd and Grefve Charles Emil Wierich Casimir Casimirsson Lewenhaupt

Forces: K. Första Lifgrenad.-Reg., K. Andra Lifgrenad.-Reg., K. Jönköpings Reg., K. Kalmar Reg., K. Smålands Husar-Reg., K. Smålands Artill.-Re. o. K. Östgora Träng-Kår.

Tredje Arméfördelningen (3rd Division)

Arméfördelningschef: Gen.-Major Carl Axel Mauritz Nordenskjöld

Stabschef: Frih. Major Curt Vilhelm Rappe

Generalstabsofficer: Grefve Kapten Carl Christian Alaric Wachtmeister

Adjutants: Bror Adam d’Orchimont and Grefve Carl Phipip Wilhelm Klingspor

Forces: K. Vestgöta Reg, K. Skaraborgs Reg. K. Elfsborgs Reg. K. Bohusläns Reg. K. Lifreg. Husarer, K. Göta Artill-Reg. K. Boden-Karlsborgs Artill.-Reg, K. Göta Ingeniör-Kår o. K. Göta Träng-Kår

Fjärde Arméfördelningen (4th Division)

Arméfördelningschef: Gen.-Löjtn. Hemming Gadd

Stabschef: Öfv.-Löjtn. Constantin Magnus Hugo Fallenius

Generalstabsofficer: Kapten Thomas Georg Nyström

Adjutants: Gregor Carl Aminoff and Per August Carlberg

Forces: K. Svea Lifgarde, K. Göta Lifgarde, K. Lifreg. Grenadierer, K. Södermansland Reg, K. Vaxholms Grenad.-Reg., K. Lifgardet till häst, K. Svea Artill-Reg., K. Svea Ingeniör-Kår, K. Fälttelegraf-Kåren, K. Svea Träng-Kår

Femte Arméfördelningen (5th Division)

Arméfördelningschef: Frih. Gen-Major Leonard Wilhelm Stjernstedt

Stabschef: Axel August Meister

Generalstabsofficer: Oscar Eugène Nygren

Adjutants: Johan Peter Fredrik Lundblad and Henrik Alexander Sebastian Tham

Forces: K. Vermlands Reg., K. Vermlands Fältjägare Reg., K. Helsinge Reg., K. Norrbottens Reg. K. Vesterbottens Reg., K. Jemptlands Fältjäg.-Reg., K. Vesternorrlands Reg. K. Norrlands Dragon-Reg., K. Norrlands Artill-Reg. o. K. Norrlands Träng-Kår

Första Arméfördelningen (1st Division)

Arméfördelningschef (Divisional Commander): Gen.Major Axel Fredrik von Matern

Stabschef (Chief of Staff): Major Alfred Henrik de Maré

Generalstabsofficer (General Staff Officer): Kapten Johan Gustaf Nanekhoff

Adjutants: Frih. Löjtn. Nils Otto Palmstierna and Frih. Löjtn. Kjell Rutger Carl Bennet

Forces: K. Karlskrona Grenad. Reg., K. Kronobergs Reg., K. Hallands Reg., K. Norra Skånska Infant.-Reg., K. Södra Skånska Infant. Reg., K. Skånska Husar-Reg., K. Skånska Dragon-Reg., Kronprinsens Husar-Reg., K. Vendes Artill. Reg., K. Skånska Träng-Kåren.

Andra Arméfördelningen (2nd Division)

Arméfördelningschef (Divisional Commander):Gen.-Major Gustaf Fredrik Oscar Uggla

Stabschef: Major Johan Axel Fabian Carleson

Generalstabsofficer: Kapten Carl Gustaf Valdemar Hammarskjöld

Adjutants: Löjtn. Carl Pehr Pontul Renterswärd and Grefve Charles Emil Wierich Casimir Casimirsson Lewenhaupt

Forces: K. Första Lifgrenad.-Reg., K. Andra Lifgrenad.-Reg., K. Jönköpings Reg., K. Kalmar Reg., K. Smålands Husar-Reg., K. Smålands Artill.-Re. o. K. Östgora Träng-Kår.

Tredje Arméfördelningen (3rd Division)

Arméfördelningschef: Gen.-Major Carl Axel Mauritz Nordenskjöld

Stabschef: Frih. Major Curt Vilhelm Rappe

Generalstabsofficer: Grefve Kapten Carl Christian Alaric Wachtmeister

Adjutants: Bror Adam d’Orchimont and Grefve Carl Phipip Wilhelm Klingspor

Forces: K. Vestgöta Reg, K. Skaraborgs Reg. K. Elfsborgs Reg. K. Bohusläns Reg. K. Lifreg. Husarer, K. Göta Artill-Reg. K. Boden-Karlsborgs Artill.-Reg, K. Göta Ingeniör-Kår o. K. Göta Träng-Kår

Fjärde Arméfördelningen (4th Division)

Arméfördelningschef: Gen.-Löjtn. Hemming Gadd

Stabschef: Öfv.-Löjtn. Constantin Magnus Hugo Fallenius

Generalstabsofficer: Kapten Thomas Georg Nyström

Adjutants: Gregor Carl Aminoff and Per August Carlberg

Forces: K. Svea Lifgarde, K. Göta Lifgarde, K. Lifreg. Grenadierer, K. Södermansland Reg, K. Vaxholms Grenad.-Reg., K. Lifgardet till häst, K. Svea Artill-Reg., K. Svea Ingeniör-Kår, K. Fälttelegraf-Kåren, K. Svea Träng-Kår

Femte Arméfördelningen (5th Division)

Arméfördelningschef: Frih. Gen-Major Leonard Wilhelm Stjernstedt

Stabschef: Axel August Meister

Generalstabsofficer: Oscar Eugène Nygren

Adjutants: Johan Peter Fredrik Lundblad and Henrik Alexander Sebastian Tham

Forces: K. Vermlands Reg., K. Vermlands Fältjägare Reg., K. Helsinge Reg., K. Norrbottens Reg. K. Vesterbottens Reg., K. Jemptlands Fältjäg.-Reg., K. Vesternorrlands Reg. K. Norrlands Dragon-Reg., K. Norrlands Artill-Reg. o. K. Norrlands Träng-Kår

Last edited:

Chapter 96: The road to Kongsvinger

11th of October, 1905, Wednesday.

Brandval, Hedmark county, Norway.

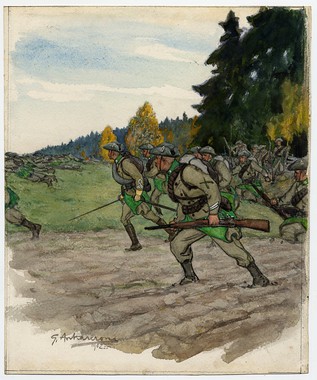

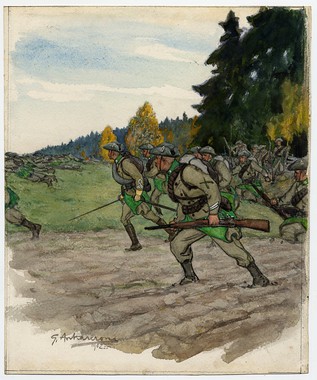

In the opening stages of the war in Scandinavia, the siege battles of the Norwegian forts along the Glomma Line were the topic that most gripped the imagination of the world. For the Norwegians, the line and the forts guarding it represented their best hope of holding the Swedish invaders at bay. Many of their strongest forts stood on the very same battlegrounds where Norwegian soldiers had fought against their eastern neighbours a century earlier.

For the Swedes, the forts were an obstacle they could not ignore, located as they were among the key positions along the hilly and narrow terrain of southeastern Norway. The Swedish war planners had ample information of the structure of the Norwegian defences and the fortifications themselves due their efficient spying efforts. The fact that many Swedish seasonal workers, the “gray geese”, had worked as stonemasons on the construction of the forts themselves provided the Swedes further information. Based on their intel, the Swedes had therefore developed a plan to seize the forts by a combination of three time-proven methods: bombardment, sapping and - if necessary - mining.

The primary target of the Swedish invasion was Kongsvinger, a small town and an important railroad junction along the northern bank of the Glomma river. The town was located next to the historical fortress of Kongsvinger, one of the key locations that had been topic of the Karlstadt negotiations before the war. While the old fortress itself had next to no military value, the two brand-new twin fort built to the Vardåsen hills just a few kilometers north from it was another story. Each armed with four 120mm Schneider-Canet L40 M/1902 shield-covered cannons, the forts were built upon solid rock, with supporting batteries located on reinforced positions on surrounding hills, surrounded by stone-reinforced trenches and barbed wire fences. The crews of each fort had their own latrines and water storages located inside housing quarters which had been built to underground tunnels inside the hills themselves. Defended by a standing garrison and supporting reservist infantry formations, the forts could control the surrounding terrain with their fire all the way to Brandval in the north to Äboken in the south. The Swedish Army simply had to neutralize the Vardåsen forts in order to proceed westwards.

The first phase of the Swedish siege plan was simple enough: the field army would swing past the northern part of the city to sever the railroad connection to Kristiania. Meanwhile the Swedish artillery was tasked to suppress the Norwegian fortified artillery positions located on hilltops surrounding the forts themselves. Controlled by forward observers via field telephone connections, the Swedish batteries assigned for this task were hidden from Norwegian counterfire. The principal defect of Swedish artillery arm, the lack of true siege guns, had been be remedied by the transfer of obsolete coastal defence guns. Placed on make-shift carriages, the motley of older 120mm, 152mm, 210mm and 240mm heavy guns had a limited supply of available ammunition and a low rate of fire. These huge weapons, firing heavy shells, could still handily penetrate most of the Norwegian concrete structures, and were perhaps the decisive element in the outcome of the siege.

The second part of the plan, a traditional component the famous sieges of previous centuries, was sapping. The stony and hilly soil was far from ideal for such work, but Swedish agricultural workers and miners were no strangers to pickaxes and shovels. The rank and file of the Swedish reservist army consisted of unquestioning, stoic, religious, nationalistic men from the countryside, led by junior reservist officers who had such middle-class civilian professions as teachers, mid-level management from commercial enterprises, shopkeepers and the like. These men who had got this far had already seen their share of fighting, and the “spirit of glorious adventure” of the first days of the war was long since gone. The units fighting their way southwards along both banks of Glomma river were already way below their original strength, and had suffered losses both because of casualties and because of single cases of desertions en route during night marches. The mood among the common soldiers was sullen. The Swedish General Staff, fearing that military discipline was on the verge of crumbling, had issued orders that special “disciplinary corps” were to be formed to prevent soldiers from retreating, by force if necessary.

For now the draconian punishments of the Regimental Law seemed to work just as well as they had done the centuries before. When given the option to choose between certain death at the front of a firing squad and a chance to fight at the frontline, the overwhelming majority of the Swedish soldiers had chosen to obey their orders, no matter what they privately thought of the war and their role in it.

The Swedish forces had crossed the Glomma river further north, and were now fighting their way southwards towards Kongsvinger along both banks of the river valley. The main cannons of the Vardåsen forts had already fired their first shots in anger against the Swedish invaders, and by now both sides were firmly aware of the main axis of Swedish attack. The normally sleepy Kongsvinger railroad station had been transformed into a busy supply hub in October, as all the fresh reinforcements the Norwegian high command could possibly muster were hastily transported to the area where both warring sides had decided to make their main effort to win the war.

Threadmarks

View all 336 threadmarks

Reader mode

Reader mode

Recent threadmarks

Chapter 316: Feuds and fundamentalists Chapter 317: The Shammar-Saudi Struggle Chapter 318: Arabian Nights Chapter 319: The Gulf and the Globe Chapter 320: House of Cards, Reshuffled Chapter 321: Pearls of the Orient Chapter 322: A Pearl of Wisdom Chapter 323: "The ink of the scholar's pen is holier than the blood of a martyr."

Share: