SameI think it'll be better if you split it into the three partsIt'll be less time consuming for people to read and we won't have to wait for the big chonker of a post

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Gold Rose: An Edward of Angoulême timeline

- Thread starter material_boy

- Start date

First government of the uncles

First government of the uncles

The regency government of the kingdom of France of 1380 to 1382 managed the affairs of state during the early minority of King Charles VI of France. It is known as the first government of the uncles, as the kingdom was governed in Charles's name by his four uncles and primarily led by his eldest uncle, Louis I, duke of Anjou, who left the regency before Charles attained his majority. The duke's departure led to the second government of the uncles.

The first government of the uncles was deeply troubled. Peasants and townsmen demanded lower taxation after a decade of war, divisions between the upper and lower nobility set the uncles against the clerks and knights who had managed government through the reign of King Charles V of France, and disagreement between the uncles themselves gave rise to factionalism and laid the foundation for future internal strife.

Background

King Charles V of France was a highly pragmatic figure praised by contemporaries for his clear, rational and strategic thinking. Coming to the throne in 1364 following the disastrous reign of his father, King Jean II of France, Charles restored royal authority and brought fiscal stability back to the realm by the end of the decade. He ended King Charles II of Navarre's pretensions to the French throne, forged an alliance with Enrique de Trastámara to depose King Pedro of Castile, and exploited the failed administration of Edward of Woodstock, prince of Wales, better known as the Black Prince, to reconquer most of Aquitaine after it had been given to the English in the 1360 Treaty of Brétigny. Charles succeeded where his father and grandfather had failed in making war on England as a result of the Fabian strategy advocated by the Breton knight Bertrand du Guesclin, who soon became Charles's top military advisor.

Louis I, duke of Anjou, was a formidable, but frighteningly ambitious man. His intense drive made him impulsive, often to his own or to his kingly brother's detriment. The second son of Jean II, he was given Anjou and Maine as an appanage, but the provinces had been ravaged by war and were quite poor as a result. Jealous of the great estates of his younger brothers, Anjou aggressively and constantly sought out ways to establish himself as one of the great men of Europe. In the 1360s, he instigated a war with Queen Giovanna I of Naples to force his claim to be heir to the county of Provence. His short campaign ended with the intervention of the pope, creating a diplomatic headache for Charles V. In the 1370s, Anjou supported his friend, the pretender King Jaume IV of Majorca, in a war against King Pere IV of Aragon. Anjou then bought the rights to Majorca from Jaume's sister after Jaume died childless, pushing Aragon toward England. The duke's freewheeling personal foreign policy was often forgiven by the king, who valued Anjou's vigorous prosecution of the war in southern France after his appointment as governor of Languedoc.

Jean, duke of Berry, was the least impressive of Jean II's four sons. He was a competent soldier, but was more interested in the grandeur of royal life. He was one of the greatest collectors of art and literature in his day and he spent freely to build and rebuild his various castles and palaces. This left him perpetually short of cash and made him dependent on the largesse of the crown despite his possession of the rich province of Poitou. He was extremely loyal to his brother Charles and was often a mediator in disputes between the nobility.

Philippe II, duke of Burgundy, was the youngest of Jean II's sons, but the most talented of them in many ways. He was a forward-thinking man, approaching every decision with consideration for how his actions may affect the future. He was a fine commander, but his true talents lay in diplomacy and politics. He was Charles V's favorite ambassador, especially to the English, with whom Burgundy had several contacts that dated back to his time as a noble prisoner of King Edward III of England. He preferred making a negotiated settlement with the English over continuing hostilities, but was not a total dove, and pushed for war when it suited his personal interests. His duchy of Burgundy was rich in its own right, but was nothing compared to the estate that his wife, Marguerite of Flanders, stood to inherit from her father, Louis II, count of Flanders. Burgundy loyally served his kingly brother, though his extreme opinion of the rights and privileges of the peers of the realm and princes of the blood predisposed him against Charles V's promotion of several lower-ranking figures in royal government.

Louis II, duke of Bourbon, was Charles V's brother-in-law. He was one of the greatest knights of the era and an exemplar of chivalry. He was not a supporter of the Fabian strategy, which he considered dishonorable, but he followed the king's orders to avoid battle without complaint and became one of the most effective commanders in the reconquest of Aquitaine and in Charles's conflict with Brittany.

Charles was never in good health. He was a sickly youth and was plagued by serious health issues after he was poisoned in a failed assassination attempt in 1359. He preoccupied himself with making plans for the future as a result of his fragile health. A downturn in his health in the mid 1370s inclined him to support peace talks with the English, eventually leading to a truce in 1375, and also led him to write a plan for the succession. In this, Charles vested the government in Anjou as regent while the custody of his son and heir was given jointly to his wife, Jeanne of Bourbon, and Burgundy. Though Charles recovered in time, his plans to split the government and the person of his son were copied by King Edward IV of England in 1377.

Hostilities between England and France resumed in 1377, but Charles's recovery was short-lived. His health declined again in 1378, which was exacerbated by the death of his beloved wife and one of their daughters. Charles looked to pause hostilities once again, but English gains in 1378 and 1379 put France in a weak negotiating position. France needed to score a new victory before opening peace talks, which it did in 1380 by grinding Gloucester's chevauchée into dust. Charles died on 16 September 1380, though, shortly before the collapse of the English campaign. He was succeeded by his eldest son, who became King Charles VI.

Chaos and coronation

Charles VI was a few months shy of his twelfth birthday when he took the throne in September 1380, around the same age that his cousin, King Edward V of England, had been when he succeeded in 1377. Charles V left a meticulous plan for young Charles's regency. It named Anjou as regent and endowed diplomatic and judicial power upon him. Burgundy and Bourbon were named as young Charles's guardians. The late king's close friend and long-serving chamberlain, Bureau de La Rivière, was vested with financial power. A long list of abbots and bishops were given various positions, but Berry was excluded from power entirely. The plan was designed to ensure that competent men loyal to the crown filled the government and that the dukes' personal ambitions were held in check.

Upon taking power, the only thing on which Charles VI's uncles could agree was that Charles V's plan for the regency was unworkable. Bureau de La Rivière was effective and highly intelligent, but he was a man of low rank who had climbed to the very top of the royal government. The uncles saw him as a parvenue who had whispered in the ear of the late king for too many years. Anjou seized control of the treasury by force, which sent Bureau de La Rivière fleeing Paris for fear of his life.

The chamberlain's fall from power left the uncles without a common enemy and they quickly turned on each other. Anjou claimed the right, as regent, to appoint a new chamberlain. Burgundy claimed such a right as the young king's co-guardian, as the chamberlain would control the flow of funds to the king's household. Bourbon, always a good soldier, wanted to follow the late king's plans as closely as possible, but even he conceded that they were cumbersome and that a more effective system was needed to prosecute the war against England and Navarre. Berry, fearing the royal spigot could be turned off unless he gained a seat at the table, proposed arranging an early coronation for Charles VI. This would formally dissolve the regency and allow the uncles to carve the government up between them thereafter. On 26 September, the uncles agreed to do just that. Charles V had been dead just 10 days and his plans for the regency had already been invalidated. Charles VI was crowned at Reims on 4 November.

On the surface, the government of the uncles looked something like that which Charles V had laid out. Anjou held the title of regent while Burgundy and Bourbon continued to act as the young king's guardians. Below the surface, though, the appointments and division of powers that Charles V had laid out were brushed aside. Anjou would manage the government and its finances, but some revenues were earmarked for the king's household to ensure money flowed freely into Burgundy's pockets. Berry was made governor of Languedoc, which allowed him to draw on all the revenues of southern France to support his lavish lifestyle. The four dukes had to agree on all major appointments and policy changes. They soon formed a council of 12, divided evenly among them, to which most work was delegated.

The first government of the uncles was divided from the start. Anjou was the senior uncle, but his younger brother Burgundy was savvier and wealthier. The two dukes argued bitterly over the order of precedence, with Anjou claiming primacy as regent while Burgundy maintained that he had priority as first peer of the realm. Their retainers routinely scuffled in the streets of Paris, each believing that the other should make way for them as servants of a higher lord. The feud spilled over into government business, such as when Anjou had to fight bitterly to name his ally, Arnaud-Amanieu, lord of Albret, as the new grand chamberlain.

A financial crisis immediately confronted the avuncular government. Charles V had recognized that years of high taxation had brought the population to a breaking point. In 1379, a tax strike in Languedoc threatened to snowball into a widespread revolt. Charles used a carrot and stick approach to quell the popular anger. First, he deployed Anjou with a small army to restore order. Then, he introduced a series of tax reforms, cutting the aides (customs duties) and fouage (hearth tax) while raising the gabelle du sel (salt tax). This headed off the revolt early, but the tax strike had seriously upset the flow of royal revenue and had put the crown in a terrible financial position. On his deathbed in September 1380, Charles outright canceled the fouage in both Languedoc and Languedoïl. It was an act of penance for the financial hardship that the people had endured throughout his reign, as Charles sought the mercy of God before his death. The cancellation of the fouage gutted royal revenue, though, and became the defining issue of Anjou's government.

Languedoïl

Charles V had planned to offset the decline in royal revenue caused by his tax cuts by expanding the royal demesne. This lay at the heart of his unpopular campaign to annex the duchy of Brittany and join it to the crown. The uncles, however, believed that the annexation had been a strategic blunder and feared that Brittany's rebellion would deliver the whole duchy over to the English. Anjou saw the opportunity to bring Brittany back into the French fold and quietly opened a diplomatic channel between Paris and Rennes. In abandoning the annexation, though, the uncles had backed themselves into a corner financially. Taxes had to be returned to their previous rates. They badly underestimated just how difficult this would be.

Estates-General of 1380

On 14 November, the Estates-General of Languedoïl met in Paris. It was the first such assembly since 1369, which had been the only meeting of Charles V's entire reign. The uncles expected the body to be compliant, believing that they could count on both the goodwill of the assembled following the coronation of their new king and also on the fear that the presence of an English army in Brittany would engender. Instead, it quickly devolved into a forum for years of pent-up frustrations and grievances.

On 15 November, just the second day of the convention, members of the Third Estate produced a formal list of complaints and recommendations for the reform of royal government. Far from approving a return to the higher taxes of the previous decade, the Third Estate embraced Charles V's deathbed decree to end the fouage. What's more, it claimed that the crown had no right to continue collecting the aides or gabelle without its consent, which it did not offer. This threatened to return France to a system where kings would need approval from the Estates-General and provincial assemblies to raise taxes. This had hamstrung King Philippe VI and Jean II during the 1340s and 50s and allowed the English to roll over vast swathes of France unchallenged. The uncles refused to even consider it, but regretted their decision just hours later.

As the uncles tussled with the Third Estate, common Parisians were whipping themselves into a frenzy just across the Seine. Anti-tax protesters in the public square grew heated as speakers lambasted the lords and decried the poverty of the people. The city's leaders stepped in too late to bring down the temperature of the crowd, fleeing the stage for fear of their lives. Calls for violence were made and, by afternoon, a mob of 300 armed men and women stormed the meeting of the Estates-General at the Palais de la Cité. Anjou went to confront them personally, but they refused to leave. The mob swelled in size as the hours passed until the duke was forced to concede to the cancellation of the aides and the gabelle in addition to the fouage that Charles V had already ended. The mob cheered the news, but did not disperse. Instead, the maddened mass crossed the bridge into the Jewish quarter. At least 16 Jewish men were murdered, their account books burned, and moveable wealth stolen in the violence that followed. It set off a sickening wave of pogroms that swept across northern France in the following months.

On 17 November, just two days after the violence, Anjou dismissed the Estates-General for fear of what else the Paris mob may do. Provincial assemblies were called to try and raise the taxes necessary to prosecute the war without the Estates-General, but the project was deemed a failure barely a month later. A radical anti-tax movement gripped the kingdom. From Champagne to the Loire to Normandy, local assemblies demanded the Estates-General be reconvened. Anjou eventually bowed to the pressure, issuing a new summons in mid December.

As the nascent anti-tax uprising threatened the government of the uncles from the outside, an internal crisis emerged. The treasury held some 200,000 francs (£33,333) upon the death of Charles V, but an incredible 30,000 francs had gone missing in the weeks since Anjou had seized control of royal finances. Burgundy openly accused Anjou of embezzling the money, an assessment with which Berry and Bourbon agreed, though it was impossible to prove. The scandal and the threat of revolt overshadowed what should have been a celebratory moment for Anjou. On 30 November, Brittany and France signed the Second Treaty of Guérande, bringing the duke of Brittany back into the French fold. Anjou, who had brokered the peace, had delivered a powerful blow to the English just months after taking power. Instead of reveling in the moment, though, he was fighting for his political life.

Financial crisis

On 14 January 1381, the Estates-General reconvened in Paris. Emboldened by the anti-tax movement in the provincial assemblies a month prior and outraged by news of Anjou's mishandling of royal funds, the Third Estate called for nothing short of the abolition of all taxes and royal financial privileges introduced since the reign of King Philippe IV early in the century. Anjou, fearing another violent uprising, reluctantly agreed in exchange for a one-year grant of the aides. This ended the widely-hated taille (direct tax on the peasantry) and the crown's right to claim a portion of all wine and other luxury goods sales.

The new tax system proved as impossible to manage in 1381 as it had generations earlier. The royal tax collectors who had been central to Charles V's tax system were set aside. Tax collection was overseen by four administrators appointed by the estates, who had limited experience in the area. Noblemen made their own tax assessments, as did town leaders for their whole towns and provincial assemblies for everything else. Administrators could only trust that everyone was being honest, as they lacked the authority to do anything besides collect the money. The process was terribly slow and it was not until autumn that it was clear revenues would fall far short of projections. France was left unable to take action against the English through the year. Indeed, it was left wide open to English attack.

Languedoc

Charles V had named Anjou as regent because of the duke's leadership in the south of France. As governor of Languedoc, Anjou had led the French reconquest of Aquitaine in the 1370s. He drove the English out of Limousin and Périgord in 1370, Poitou in 1372, Angoulême and Saintonge in 1373, Agenais in 1374, and nearly conquered the rump state of Gascony in 1377. He moved to Paris thereafter, as the French shifted focus to the northern theater of war, and became an absent governor. Anjou relinquished the office to his younger brother, the duke of Berry, when they formed the government of the uncles.

Armagnac and Foix

Berry was uniquely unsuited for his new position because his wife was Jeanne of Armagnac, a sister of one of the two great lords of southern France. Upon Berry's appointment in 1380, Jean II, count of Armagnac, and Gaston III, count of Foix, had only recently concluded the Comminges War, in which the two men struggled for control of a neighboring heiress and her lands. The peace was fragile and a sudden appearance by Armagnac's brother-in-law threatened to tip the delicate balance of power they had established.

Foix wasted no time in gathering an army to protect himself. He had 3,000 men at his back by the time Berry finally reached the region in June 1381. Armagnac met Berry with 2,500 of his own men, pledging to defend the duke against Foix's aggression. Foix, however, had no intention of attacking the duke. Instead, he set a subtle trap for Armagnac.

Foix sued for peace before a single drop of blood had been shed. He played to Berry's ego, saying that the appearance of such a magnificent and powerful prince had struck fear in his heart. He said that it was not his intention to do harm to the duke, but to protect himself against Armagnac, who he (Foix) feared may manipulate the duke into joining a new war for control of the south. Berry was charmed. The two men negotiated a deal in which all appointments to royal offices in the south were to be divided between supporters of the two counts and Berry pledged to act fairly in all matters. On 15 July, Berry and Foix formally sealed a treaty confirming these details in a ceremony at Revel. Armagnac was outraged. The count stormed north with his army in protest. It was exactly the response for which Foix had hoped.

On 21 July, Yvain de Foix, a bastard son of the count, led his father's army in an ambush of the Armagnacs as they moved north through Rabastens. Caught completely by surprise, the Armagnacs were massacred. According to one account, just 300 of Armagnac's 2,500 men survived.

Berry was furious at news of the battle. He declared Foix's attack a double-cross of their agreement, but the count rightly pointed out that Armagnac was leading his army into Fuxéen lands, which Foix had a duty and a right to defend. Berry conceded that the attack was justified, outraging Armagnac. Relations between the two brothers-in-law never recovered. Armagnac's power and prestige never recovered either. The slaughter at Rabastens effectively neutered the count and left Foix as the dominant figure in the south.

England and Gascony

Berry's English counterpart in the south was John Neville, 3rd baron Neville, who had been lord lieutenant of Aquitaine since 1378. Neville had saved Mortagne, one of the last major English positions in Saintonge, and secured Gascony's border by capturing at least four dozen fortified positions on the frontiers of Angoumois and Périgord in 1379. Plans for the reconquest of Agenais in 1380 had to be put on hold, though, as English and Gascon men and resources went to support Navarre when it faced a Castilian invasion. Neville's lieutenancy was supposed to expire in 1381, but he was awarded a second term.

In late 1380, Bertucat d'Albret, a bastard-born knight from a storied Gascon family, made contact with Neville and offered to help transform the English position in Gascony. Albret, a famed routier captain, had stayed in Aquitaine as many others headed to Navarre. In October 1380, a pair of major fortresses in central France, Carlat and Le Saillant, were taken by two of Albret's lieutenants. They pushed out from these strongholds to take control of several walled towns in the surrounding area, creating a ring of defensive positions. It was the beginning of a strong network of routier garrisons loyal to Albret, which would later become known as the Confederation of Carlat.

Carlat and Le Saillant were located in Auvergne, far from English Gascony. Albret proposed launching raids from there deep into France to sow chaos and draw French defenders away from the Gascon border. This would give Neville the chance to mount a new offensive. Albret did not present this plan altruistically and asked that Edward V grant him land in Gascony that would make him a lord on par with other members of his family. He even sailed to London to make his case directly to the duke of Lancaster, who was the young Edward's regent. He secured the backing of the English crown in early 1381.

The timing of Albret's mission to England could not have been better. In fall 1380, the duke of Gloucester had requested reinforcements for the siege of Nantes. By the time the army was ready to sail, though, the duke of Brittany had betrayed the English and Gloucester had been forced to quit the siege. As a result, the English had 2,000 men assembled at Dartmouth with no place to go. It was an easy decision to ship them off to Bordeaux to support Neville as a part of Albret's plans.

As the snows melted in the passes through the Pyrenees, the routiers who had gone to serve Navarre the year before began to return to southern France. Many joined the service of the counts of Armagnac or Foix, as the two lords constantly employed at least some companies, but most returned to whatever land they had menaced before the war between Castile and Navarre. The result was that southern France was already suffering a surge of violence even before Albret's plan was set in motion.

The landing of 2,000 Englishmen at Bordeaux could not have escaped French notice, but there appears to have been no effort to shore up the defense of the Gascon march. Berry did not even arrive in the region until June and was then sucked into the conflict between Armagnac and Foix. The only real government action that year was an effort by Louis de Sancerre, marshal of France, to dislodge the routier companies from their positions in Auvergne and Limousin, but he withdrew after a series of attacks on his supply train.

Once Sancerre had been driven off, Albret put his plan in motion. Perrot de Béarn, a routier captain who was friendly with Albret, but not a member of the Confederation of Carlat, began raiding west from Limousin into Angoumois in July. Albret's protégé, Ramonet de Sort, led a contingent of the confederation's forces south through Quercy, capturing the royal castle of Penne, and began raiding into Languedoc. Albret himself took another contingent west through Quercy to Agenais. Working in close concert with the routiers, Gaillard II de Durfort, lord of Duras, the most powerful Anglo-Gascon lord in Agenais, moved east, rooting scores of Franco-Gascon lords and knights from their positions.

On 1 August, Neville led the English army across the Dordogne into Saintonge. Three years earlier, he had staged a relief campaign here in the opening weeks of his lieutenancy. At the time, it was the first English action in Saintonge since the early 70s. Now, he aimed to conquer the region in its entirety.

Albret's plan worked well, Franco-Gascons in Saintonge had moved to confront Perrot de Béarn's routiers as they approached through Angoumois, denuding the region of French defenders ahead of Neville's attack. In just three weeks time, Neville had swept over everything all the way to Archiac. The small castle there was made Neville's headquarters while he and his captains planned an attack on Saintes, the region's capital. Jean II de Nesle, lord of Mello, caught on to the English plan and urgently recalled about 600 men-at-arms to Saintes. The English took control of the surrounding towns and prepared for a siege.

On 28 August, a direct assault was repulsed with heavy casualties. Neville ordered that siegeworks be constructed. It was not a quick or easy task, but on 9 September, the town awoke to the blasts of English trumpets. English artillery was in place, the trumpets sounding the attack. The townspeople turned against the lord of Mello, fearing a sack if the town fell. Unable to control the local population and defend against the English, Mello sued for terms. Neville allowed Mello and his men to withdraw to Poitou, taking control of the capital.

By the end of the year, England had control of Saintonge for the first time in nearly a decade and the march of Gascony—the porous border region between areas of clear English and French control, where a messy patchwork of lordships was dominated by local alliances and rivalries—was pushed west across Agenais. The routiers abandoned Languedoc for a time as a result of the Tuchin Revolt, but they broke through the duke of Bourbon's defenses and raided his lands all the way to the Loire.

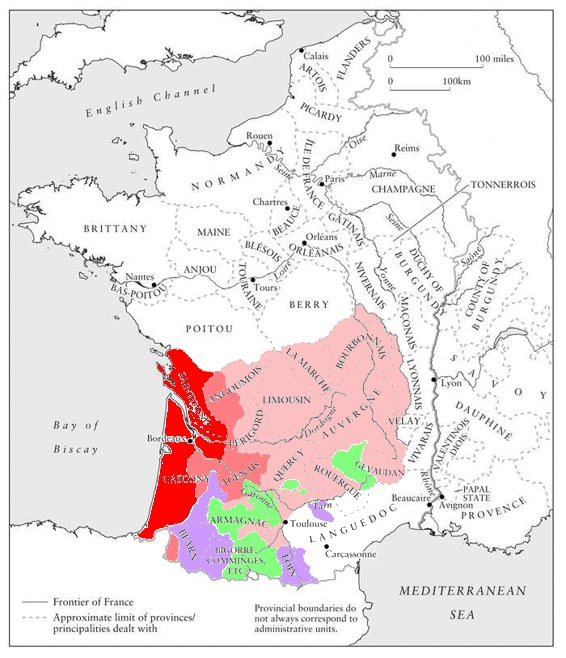

Southern France before and after the 1381 campaign

Red: Territories of King Edward V of England

Light red: Gascon marches, controlled by local lords

Very light red: Range of routier company raiding parties

Aquamarine: Territories of Jean II, count of Armagnac

Lavender: Territories of Gaston III, count of Foix

The Gascon campaign of 1381 was the most successful year of fighting for the English since the beginning of the Caroline War. English hopes that the campaign could be used as a blueprint for the reconquest of Aquitaine were soon disappointed, though. An anti-tax revolt in southern England that same summer spooked parliament, which refused to grant taxation for years thereafter. An Urbanist crusade was then sanctioned in the fall, drawing English attention away from Aquitaine and to Castile. Bertucat d'Albret then died suddenly in 1382, which was a major loss for the English in the region. Finally, in 1383, England and France agreed to a truce that took the possibility of another major campaign off the table entirely.

Tuchin Revolt

The duke of Berry's appointment to the governorship of Languedoc in 1380 coincided with an ebb in routier activity, as many were drawn south to Navarre as part of that kingdom's war with Castile. The Navarrese victory over Castile at the Battle of Estella kept many of the routiers there over winter, raiding into the Castilian countryside and threatening unwalled towns and villages until they were bribed into leaving the area. As the routiers trickled back into France through late 1380 and 1381, though, violence again became part of everyday life. This routier resurgence provoked a shocking backlash.

On 8 September 1381, tax collectors in the town of Béziers were met by a large protest of townspeople. The locals, decrying routier activity in the area, demanded answers from the taxmen as to how their money was being spent, as clearly it was not going to their own defense. The protest turned violent. The tax collectors fled to a nearby tower, but the mob set it ablaze. It burned to the ground with the officials inside.

Government officials became targets of violence across the region through the fall. Accountants and tax collectors were hanged. Local officials did not defend representatives of royal government for fear of their own lives. More remarkably, though, the peasants and poor townsmen who were forming these mobs soon began to organize themselves into local watches to fight back against the terror of the routiers. The smallest of the routier companies, which were little more than roving gangs, were butchered. The brutality with which the Tuchins, as the rebels came to be called, exacted their revenge was so extreme that the archbishop of Toulouse condemned them more strongly than he did the routiers themselves.

Berry sent a cadre of knights to pacify the area around Béziers and to execute the leaders of the revolt. The appearance of an elite fighting force, heavily armored and mounted, was typically enough to frighten even large numbers of commoners into submission. Not this time. The men and women of the Tuchins were desperate. They had lived in fear of the routiers for decades. Years of heavy taxation had robbed them of everything the routiers had not stolen. They stood together at Béziers, unarmored and armed with whatever they could find with which to fight, as the knights charged. Utterly shocked that the mob had not broken up ahead of the charge, the confused knights were caught up in a mass of people grabbing at them and the reins of their horses. Knights were pulled from their rides or the animals were killed under them. Their helmets were torn off, their eyes stabbed and their heads bashed in with rocks.

The Massacre of Béziers left at least 41 townsmen and three knights dead. It was the beginning of a mass movement unlike anything France had ever seen. There was an explosion of violence against authorities and routiers alike. Organized by a handful of country squires, the Tuchins even attacked some smaller defensive positions held by minor lords or being used as routier headquarters. Screams of "kill the lords" and "kill the rich" became rallying cries at protests in cities and towns. It seemed that a revolution could be underway south of the Tarn.

Naples

By the end of 1381, only a year after the death of Charles V, the first government of the uncles was on the verge of collapse. The Estates-General of Languedoïl had effectively cut off any revenues from the north. The Estates-General of Languedoc could not even call a meeting, as so much of the south was in open revolt and much of the rest was being preyed upon by the routiers, making travel dangerous. The English had retaken control of Saintogne. Northern France was dangerously exposed to attack, as garrisons on the march of Calais and the coast of Normandy were being hollowed out by desertions for lack of pay. The crown was piling up huge debts that it had no ability to repay.

Anjou had no response to the burgeoning crises, as his personal ambitions had already eclipsed his interest in the regency. In 1380, Anjou had been named heir to the childless Queen Giovanna I of Naples, who had been alienated by Pope Urban VI of Rome. As the church was split between two rival popes at the time, Giovanna switched her obedience to Pope Clement VII of Avignon. She was then deposed by her cousin, Carlo of Durazzo, in the first Urbanist crusade. In fall 1381, Anjou came under immense pressure from the Avignon pontiff to lead an expedition to restore the queen of Naples and secure his inheritance. In early 1382, Anjou resigned his position as regent and left Paris to launch a Clementist counter-crusade.

Aftermath

The first government of the uncles was judged to be a failure by contemporaries and most modern historians agree with that verdict. Charles V was considered a great man in his own day, but his greatness came at a terrible cost. Popular anger over taxation and the conduct of the war had been simmering for years. The king, uniquely attuned to the mood of the county, had kept that anger from boiling over. It would have been difficult for anyone to hold France together after his death, but the duke of Anjou was completely unsuited for the role of regent at such a time. Ambitious, imperious, and short-sighted, he often seemed more interested in asserting himself over his brother Burgundy than he did in resolving the problems that faced the country. Burgundy was their father's favorite son, one of their kingly brother's most influential advisors, and set to become the wealthiest man in France, as his wife was the greatest heiress in western Europe. Anjou's jealousy of his younger brother drove his pursuit of the crown of Naples to a point where the regency became more of a distraction than a duty or honor.

Anjou's departure left Burgundy as the dominant force in France, beginning the second government of the uncles. The new regime had to reckon with the financial crisis that Anjou had left in his wake, revolts in Flanders and Languedoc, and the war with England. Anjou's Crusade launched in the spring.

The regency government of the kingdom of France of 1380 to 1382 managed the affairs of state during the early minority of King Charles VI of France. It is known as the first government of the uncles, as the kingdom was governed in Charles's name by his four uncles and primarily led by his eldest uncle, Louis I, duke of Anjou, who left the regency before Charles attained his majority. The duke's departure led to the second government of the uncles.

The first government of the uncles was deeply troubled. Peasants and townsmen demanded lower taxation after a decade of war, divisions between the upper and lower nobility set the uncles against the clerks and knights who had managed government through the reign of King Charles V of France, and disagreement between the uncles themselves gave rise to factionalism and laid the foundation for future internal strife.

Background

King Charles V of France was a highly pragmatic figure praised by contemporaries for his clear, rational and strategic thinking. Coming to the throne in 1364 following the disastrous reign of his father, King Jean II of France, Charles restored royal authority and brought fiscal stability back to the realm by the end of the decade. He ended King Charles II of Navarre's pretensions to the French throne, forged an alliance with Enrique de Trastámara to depose King Pedro of Castile, and exploited the failed administration of Edward of Woodstock, prince of Wales, better known as the Black Prince, to reconquer most of Aquitaine after it had been given to the English in the 1360 Treaty of Brétigny. Charles succeeded where his father and grandfather had failed in making war on England as a result of the Fabian strategy advocated by the Breton knight Bertrand du Guesclin, who soon became Charles's top military advisor.

Louis I, duke of Anjou, was a formidable, but frighteningly ambitious man. His intense drive made him impulsive, often to his own or to his kingly brother's detriment. The second son of Jean II, he was given Anjou and Maine as an appanage, but the provinces had been ravaged by war and were quite poor as a result. Jealous of the great estates of his younger brothers, Anjou aggressively and constantly sought out ways to establish himself as one of the great men of Europe. In the 1360s, he instigated a war with Queen Giovanna I of Naples to force his claim to be heir to the county of Provence. His short campaign ended with the intervention of the pope, creating a diplomatic headache for Charles V. In the 1370s, Anjou supported his friend, the pretender King Jaume IV of Majorca, in a war against King Pere IV of Aragon. Anjou then bought the rights to Majorca from Jaume's sister after Jaume died childless, pushing Aragon toward England. The duke's freewheeling personal foreign policy was often forgiven by the king, who valued Anjou's vigorous prosecution of the war in southern France after his appointment as governor of Languedoc.

Jean, duke of Berry, was the least impressive of Jean II's four sons. He was a competent soldier, but was more interested in the grandeur of royal life. He was one of the greatest collectors of art and literature in his day and he spent freely to build and rebuild his various castles and palaces. This left him perpetually short of cash and made him dependent on the largesse of the crown despite his possession of the rich province of Poitou. He was extremely loyal to his brother Charles and was often a mediator in disputes between the nobility.

Philippe II, duke of Burgundy, was the youngest of Jean II's sons, but the most talented of them in many ways. He was a forward-thinking man, approaching every decision with consideration for how his actions may affect the future. He was a fine commander, but his true talents lay in diplomacy and politics. He was Charles V's favorite ambassador, especially to the English, with whom Burgundy had several contacts that dated back to his time as a noble prisoner of King Edward III of England. He preferred making a negotiated settlement with the English over continuing hostilities, but was not a total dove, and pushed for war when it suited his personal interests. His duchy of Burgundy was rich in its own right, but was nothing compared to the estate that his wife, Marguerite of Flanders, stood to inherit from her father, Louis II, count of Flanders. Burgundy loyally served his kingly brother, though his extreme opinion of the rights and privileges of the peers of the realm and princes of the blood predisposed him against Charles V's promotion of several lower-ranking figures in royal government.

Louis II, duke of Bourbon, was Charles V's brother-in-law. He was one of the greatest knights of the era and an exemplar of chivalry. He was not a supporter of the Fabian strategy, which he considered dishonorable, but he followed the king's orders to avoid battle without complaint and became one of the most effective commanders in the reconquest of Aquitaine and in Charles's conflict with Brittany.

Charles was never in good health. He was a sickly youth and was plagued by serious health issues after he was poisoned in a failed assassination attempt in 1359. He preoccupied himself with making plans for the future as a result of his fragile health. A downturn in his health in the mid 1370s inclined him to support peace talks with the English, eventually leading to a truce in 1375, and also led him to write a plan for the succession. In this, Charles vested the government in Anjou as regent while the custody of his son and heir was given jointly to his wife, Jeanne of Bourbon, and Burgundy. Though Charles recovered in time, his plans to split the government and the person of his son were copied by King Edward IV of England in 1377.

Hostilities between England and France resumed in 1377, but Charles's recovery was short-lived. His health declined again in 1378, which was exacerbated by the death of his beloved wife and one of their daughters. Charles looked to pause hostilities once again, but English gains in 1378 and 1379 put France in a weak negotiating position. France needed to score a new victory before opening peace talks, which it did in 1380 by grinding Gloucester's chevauchée into dust. Charles died on 16 September 1380, though, shortly before the collapse of the English campaign. He was succeeded by his eldest son, who became King Charles VI.

Chaos and coronation

Charles VI was a few months shy of his twelfth birthday when he took the throne in September 1380, around the same age that his cousin, King Edward V of England, had been when he succeeded in 1377. Charles V left a meticulous plan for young Charles's regency. It named Anjou as regent and endowed diplomatic and judicial power upon him. Burgundy and Bourbon were named as young Charles's guardians. The late king's close friend and long-serving chamberlain, Bureau de La Rivière, was vested with financial power. A long list of abbots and bishops were given various positions, but Berry was excluded from power entirely. The plan was designed to ensure that competent men loyal to the crown filled the government and that the dukes' personal ambitions were held in check.

Upon taking power, the only thing on which Charles VI's uncles could agree was that Charles V's plan for the regency was unworkable. Bureau de La Rivière was effective and highly intelligent, but he was a man of low rank who had climbed to the very top of the royal government. The uncles saw him as a parvenue who had whispered in the ear of the late king for too many years. Anjou seized control of the treasury by force, which sent Bureau de La Rivière fleeing Paris for fear of his life.

The chamberlain's fall from power left the uncles without a common enemy and they quickly turned on each other. Anjou claimed the right, as regent, to appoint a new chamberlain. Burgundy claimed such a right as the young king's co-guardian, as the chamberlain would control the flow of funds to the king's household. Bourbon, always a good soldier, wanted to follow the late king's plans as closely as possible, but even he conceded that they were cumbersome and that a more effective system was needed to prosecute the war against England and Navarre. Berry, fearing the royal spigot could be turned off unless he gained a seat at the table, proposed arranging an early coronation for Charles VI. This would formally dissolve the regency and allow the uncles to carve the government up between them thereafter. On 26 September, the uncles agreed to do just that. Charles V had been dead just 10 days and his plans for the regency had already been invalidated. Charles VI was crowned at Reims on 4 November.

On the surface, the government of the uncles looked something like that which Charles V had laid out. Anjou held the title of regent while Burgundy and Bourbon continued to act as the young king's guardians. Below the surface, though, the appointments and division of powers that Charles V had laid out were brushed aside. Anjou would manage the government and its finances, but some revenues were earmarked for the king's household to ensure money flowed freely into Burgundy's pockets. Berry was made governor of Languedoc, which allowed him to draw on all the revenues of southern France to support his lavish lifestyle. The four dukes had to agree on all major appointments and policy changes. They soon formed a council of 12, divided evenly among them, to which most work was delegated.

The first government of the uncles was divided from the start. Anjou was the senior uncle, but his younger brother Burgundy was savvier and wealthier. The two dukes argued bitterly over the order of precedence, with Anjou claiming primacy as regent while Burgundy maintained that he had priority as first peer of the realm. Their retainers routinely scuffled in the streets of Paris, each believing that the other should make way for them as servants of a higher lord. The feud spilled over into government business, such as when Anjou had to fight bitterly to name his ally, Arnaud-Amanieu, lord of Albret, as the new grand chamberlain.

A financial crisis immediately confronted the avuncular government. Charles V had recognized that years of high taxation had brought the population to a breaking point. In 1379, a tax strike in Languedoc threatened to snowball into a widespread revolt. Charles used a carrot and stick approach to quell the popular anger. First, he deployed Anjou with a small army to restore order. Then, he introduced a series of tax reforms, cutting the aides (customs duties) and fouage (hearth tax) while raising the gabelle du sel (salt tax). This headed off the revolt early, but the tax strike had seriously upset the flow of royal revenue and had put the crown in a terrible financial position. On his deathbed in September 1380, Charles outright canceled the fouage in both Languedoc and Languedoïl. It was an act of penance for the financial hardship that the people had endured throughout his reign, as Charles sought the mercy of God before his death. The cancellation of the fouage gutted royal revenue, though, and became the defining issue of Anjou's government.

Languedoïl

Charles V had planned to offset the decline in royal revenue caused by his tax cuts by expanding the royal demesne. This lay at the heart of his unpopular campaign to annex the duchy of Brittany and join it to the crown. The uncles, however, believed that the annexation had been a strategic blunder and feared that Brittany's rebellion would deliver the whole duchy over to the English. Anjou saw the opportunity to bring Brittany back into the French fold and quietly opened a diplomatic channel between Paris and Rennes. In abandoning the annexation, though, the uncles had backed themselves into a corner financially. Taxes had to be returned to their previous rates. They badly underestimated just how difficult this would be.

Estates-General of 1380

On 14 November, the Estates-General of Languedoïl met in Paris. It was the first such assembly since 1369, which had been the only meeting of Charles V's entire reign. The uncles expected the body to be compliant, believing that they could count on both the goodwill of the assembled following the coronation of their new king and also on the fear that the presence of an English army in Brittany would engender. Instead, it quickly devolved into a forum for years of pent-up frustrations and grievances.

On 15 November, just the second day of the convention, members of the Third Estate produced a formal list of complaints and recommendations for the reform of royal government. Far from approving a return to the higher taxes of the previous decade, the Third Estate embraced Charles V's deathbed decree to end the fouage. What's more, it claimed that the crown had no right to continue collecting the aides or gabelle without its consent, which it did not offer. This threatened to return France to a system where kings would need approval from the Estates-General and provincial assemblies to raise taxes. This had hamstrung King Philippe VI and Jean II during the 1340s and 50s and allowed the English to roll over vast swathes of France unchallenged. The uncles refused to even consider it, but regretted their decision just hours later.

As the uncles tussled with the Third Estate, common Parisians were whipping themselves into a frenzy just across the Seine. Anti-tax protesters in the public square grew heated as speakers lambasted the lords and decried the poverty of the people. The city's leaders stepped in too late to bring down the temperature of the crowd, fleeing the stage for fear of their lives. Calls for violence were made and, by afternoon, a mob of 300 armed men and women stormed the meeting of the Estates-General at the Palais de la Cité. Anjou went to confront them personally, but they refused to leave. The mob swelled in size as the hours passed until the duke was forced to concede to the cancellation of the aides and the gabelle in addition to the fouage that Charles V had already ended. The mob cheered the news, but did not disperse. Instead, the maddened mass crossed the bridge into the Jewish quarter. At least 16 Jewish men were murdered, their account books burned, and moveable wealth stolen in the violence that followed. It set off a sickening wave of pogroms that swept across northern France in the following months.

On 17 November, just two days after the violence, Anjou dismissed the Estates-General for fear of what else the Paris mob may do. Provincial assemblies were called to try and raise the taxes necessary to prosecute the war without the Estates-General, but the project was deemed a failure barely a month later. A radical anti-tax movement gripped the kingdom. From Champagne to the Loire to Normandy, local assemblies demanded the Estates-General be reconvened. Anjou eventually bowed to the pressure, issuing a new summons in mid December.

As the nascent anti-tax uprising threatened the government of the uncles from the outside, an internal crisis emerged. The treasury held some 200,000 francs (£33,333) upon the death of Charles V, but an incredible 30,000 francs had gone missing in the weeks since Anjou had seized control of royal finances. Burgundy openly accused Anjou of embezzling the money, an assessment with which Berry and Bourbon agreed, though it was impossible to prove. The scandal and the threat of revolt overshadowed what should have been a celebratory moment for Anjou. On 30 November, Brittany and France signed the Second Treaty of Guérande, bringing the duke of Brittany back into the French fold. Anjou, who had brokered the peace, had delivered a powerful blow to the English just months after taking power. Instead of reveling in the moment, though, he was fighting for his political life.

Financial crisis

On 14 January 1381, the Estates-General reconvened in Paris. Emboldened by the anti-tax movement in the provincial assemblies a month prior and outraged by news of Anjou's mishandling of royal funds, the Third Estate called for nothing short of the abolition of all taxes and royal financial privileges introduced since the reign of King Philippe IV early in the century. Anjou, fearing another violent uprising, reluctantly agreed in exchange for a one-year grant of the aides. This ended the widely-hated taille (direct tax on the peasantry) and the crown's right to claim a portion of all wine and other luxury goods sales.

The new tax system proved as impossible to manage in 1381 as it had generations earlier. The royal tax collectors who had been central to Charles V's tax system were set aside. Tax collection was overseen by four administrators appointed by the estates, who had limited experience in the area. Noblemen made their own tax assessments, as did town leaders for their whole towns and provincial assemblies for everything else. Administrators could only trust that everyone was being honest, as they lacked the authority to do anything besides collect the money. The process was terribly slow and it was not until autumn that it was clear revenues would fall far short of projections. France was left unable to take action against the English through the year. Indeed, it was left wide open to English attack.

Languedoc

Charles V had named Anjou as regent because of the duke's leadership in the south of France. As governor of Languedoc, Anjou had led the French reconquest of Aquitaine in the 1370s. He drove the English out of Limousin and Périgord in 1370, Poitou in 1372, Angoulême and Saintonge in 1373, Agenais in 1374, and nearly conquered the rump state of Gascony in 1377. He moved to Paris thereafter, as the French shifted focus to the northern theater of war, and became an absent governor. Anjou relinquished the office to his younger brother, the duke of Berry, when they formed the government of the uncles.

Armagnac and Foix

Berry was uniquely unsuited for his new position because his wife was Jeanne of Armagnac, a sister of one of the two great lords of southern France. Upon Berry's appointment in 1380, Jean II, count of Armagnac, and Gaston III, count of Foix, had only recently concluded the Comminges War, in which the two men struggled for control of a neighboring heiress and her lands. The peace was fragile and a sudden appearance by Armagnac's brother-in-law threatened to tip the delicate balance of power they had established.

Foix wasted no time in gathering an army to protect himself. He had 3,000 men at his back by the time Berry finally reached the region in June 1381. Armagnac met Berry with 2,500 of his own men, pledging to defend the duke against Foix's aggression. Foix, however, had no intention of attacking the duke. Instead, he set a subtle trap for Armagnac.

Foix sued for peace before a single drop of blood had been shed. He played to Berry's ego, saying that the appearance of such a magnificent and powerful prince had struck fear in his heart. He said that it was not his intention to do harm to the duke, but to protect himself against Armagnac, who he (Foix) feared may manipulate the duke into joining a new war for control of the south. Berry was charmed. The two men negotiated a deal in which all appointments to royal offices in the south were to be divided between supporters of the two counts and Berry pledged to act fairly in all matters. On 15 July, Berry and Foix formally sealed a treaty confirming these details in a ceremony at Revel. Armagnac was outraged. The count stormed north with his army in protest. It was exactly the response for which Foix had hoped.

On 21 July, Yvain de Foix, a bastard son of the count, led his father's army in an ambush of the Armagnacs as they moved north through Rabastens. Caught completely by surprise, the Armagnacs were massacred. According to one account, just 300 of Armagnac's 2,500 men survived.

Berry was furious at news of the battle. He declared Foix's attack a double-cross of their agreement, but the count rightly pointed out that Armagnac was leading his army into Fuxéen lands, which Foix had a duty and a right to defend. Berry conceded that the attack was justified, outraging Armagnac. Relations between the two brothers-in-law never recovered. Armagnac's power and prestige never recovered either. The slaughter at Rabastens effectively neutered the count and left Foix as the dominant figure in the south.

England and Gascony

Berry's English counterpart in the south was John Neville, 3rd baron Neville, who had been lord lieutenant of Aquitaine since 1378. Neville had saved Mortagne, one of the last major English positions in Saintonge, and secured Gascony's border by capturing at least four dozen fortified positions on the frontiers of Angoumois and Périgord in 1379. Plans for the reconquest of Agenais in 1380 had to be put on hold, though, as English and Gascon men and resources went to support Navarre when it faced a Castilian invasion. Neville's lieutenancy was supposed to expire in 1381, but he was awarded a second term.

In late 1380, Bertucat d'Albret, a bastard-born knight from a storied Gascon family, made contact with Neville and offered to help transform the English position in Gascony. Albret, a famed routier captain, had stayed in Aquitaine as many others headed to Navarre. In October 1380, a pair of major fortresses in central France, Carlat and Le Saillant, were taken by two of Albret's lieutenants. They pushed out from these strongholds to take control of several walled towns in the surrounding area, creating a ring of defensive positions. It was the beginning of a strong network of routier garrisons loyal to Albret, which would later become known as the Confederation of Carlat.

Carlat and Le Saillant were located in Auvergne, far from English Gascony. Albret proposed launching raids from there deep into France to sow chaos and draw French defenders away from the Gascon border. This would give Neville the chance to mount a new offensive. Albret did not present this plan altruistically and asked that Edward V grant him land in Gascony that would make him a lord on par with other members of his family. He even sailed to London to make his case directly to the duke of Lancaster, who was the young Edward's regent. He secured the backing of the English crown in early 1381.

The timing of Albret's mission to England could not have been better. In fall 1380, the duke of Gloucester had requested reinforcements for the siege of Nantes. By the time the army was ready to sail, though, the duke of Brittany had betrayed the English and Gloucester had been forced to quit the siege. As a result, the English had 2,000 men assembled at Dartmouth with no place to go. It was an easy decision to ship them off to Bordeaux to support Neville as a part of Albret's plans.

As the snows melted in the passes through the Pyrenees, the routiers who had gone to serve Navarre the year before began to return to southern France. Many joined the service of the counts of Armagnac or Foix, as the two lords constantly employed at least some companies, but most returned to whatever land they had menaced before the war between Castile and Navarre. The result was that southern France was already suffering a surge of violence even before Albret's plan was set in motion.

The landing of 2,000 Englishmen at Bordeaux could not have escaped French notice, but there appears to have been no effort to shore up the defense of the Gascon march. Berry did not even arrive in the region until June and was then sucked into the conflict between Armagnac and Foix. The only real government action that year was an effort by Louis de Sancerre, marshal of France, to dislodge the routier companies from their positions in Auvergne and Limousin, but he withdrew after a series of attacks on his supply train.

Once Sancerre had been driven off, Albret put his plan in motion. Perrot de Béarn, a routier captain who was friendly with Albret, but not a member of the Confederation of Carlat, began raiding west from Limousin into Angoumois in July. Albret's protégé, Ramonet de Sort, led a contingent of the confederation's forces south through Quercy, capturing the royal castle of Penne, and began raiding into Languedoc. Albret himself took another contingent west through Quercy to Agenais. Working in close concert with the routiers, Gaillard II de Durfort, lord of Duras, the most powerful Anglo-Gascon lord in Agenais, moved east, rooting scores of Franco-Gascon lords and knights from their positions.

On 1 August, Neville led the English army across the Dordogne into Saintonge. Three years earlier, he had staged a relief campaign here in the opening weeks of his lieutenancy. At the time, it was the first English action in Saintonge since the early 70s. Now, he aimed to conquer the region in its entirety.

Albret's plan worked well, Franco-Gascons in Saintonge had moved to confront Perrot de Béarn's routiers as they approached through Angoumois, denuding the region of French defenders ahead of Neville's attack. In just three weeks time, Neville had swept over everything all the way to Archiac. The small castle there was made Neville's headquarters while he and his captains planned an attack on Saintes, the region's capital. Jean II de Nesle, lord of Mello, caught on to the English plan and urgently recalled about 600 men-at-arms to Saintes. The English took control of the surrounding towns and prepared for a siege.

On 28 August, a direct assault was repulsed with heavy casualties. Neville ordered that siegeworks be constructed. It was not a quick or easy task, but on 9 September, the town awoke to the blasts of English trumpets. English artillery was in place, the trumpets sounding the attack. The townspeople turned against the lord of Mello, fearing a sack if the town fell. Unable to control the local population and defend against the English, Mello sued for terms. Neville allowed Mello and his men to withdraw to Poitou, taking control of the capital.

By the end of the year, England had control of Saintonge for the first time in nearly a decade and the march of Gascony—the porous border region between areas of clear English and French control, where a messy patchwork of lordships was dominated by local alliances and rivalries—was pushed west across Agenais. The routiers abandoned Languedoc for a time as a result of the Tuchin Revolt, but they broke through the duke of Bourbon's defenses and raided his lands all the way to the Loire.

Southern France before and after the 1381 campaign

Red: Territories of King Edward V of England

Light red: Gascon marches, controlled by local lords

Very light red: Range of routier company raiding parties

Aquamarine: Territories of Jean II, count of Armagnac

Lavender: Territories of Gaston III, count of Foix

The Gascon campaign of 1381 was the most successful year of fighting for the English since the beginning of the Caroline War. English hopes that the campaign could be used as a blueprint for the reconquest of Aquitaine were soon disappointed, though. An anti-tax revolt in southern England that same summer spooked parliament, which refused to grant taxation for years thereafter. An Urbanist crusade was then sanctioned in the fall, drawing English attention away from Aquitaine and to Castile. Bertucat d'Albret then died suddenly in 1382, which was a major loss for the English in the region. Finally, in 1383, England and France agreed to a truce that took the possibility of another major campaign off the table entirely.

Tuchin Revolt

The duke of Berry's appointment to the governorship of Languedoc in 1380 coincided with an ebb in routier activity, as many were drawn south to Navarre as part of that kingdom's war with Castile. The Navarrese victory over Castile at the Battle of Estella kept many of the routiers there over winter, raiding into the Castilian countryside and threatening unwalled towns and villages until they were bribed into leaving the area. As the routiers trickled back into France through late 1380 and 1381, though, violence again became part of everyday life. This routier resurgence provoked a shocking backlash.

On 8 September 1381, tax collectors in the town of Béziers were met by a large protest of townspeople. The locals, decrying routier activity in the area, demanded answers from the taxmen as to how their money was being spent, as clearly it was not going to their own defense. The protest turned violent. The tax collectors fled to a nearby tower, but the mob set it ablaze. It burned to the ground with the officials inside.

Government officials became targets of violence across the region through the fall. Accountants and tax collectors were hanged. Local officials did not defend representatives of royal government for fear of their own lives. More remarkably, though, the peasants and poor townsmen who were forming these mobs soon began to organize themselves into local watches to fight back against the terror of the routiers. The smallest of the routier companies, which were little more than roving gangs, were butchered. The brutality with which the Tuchins, as the rebels came to be called, exacted their revenge was so extreme that the archbishop of Toulouse condemned them more strongly than he did the routiers themselves.

Berry sent a cadre of knights to pacify the area around Béziers and to execute the leaders of the revolt. The appearance of an elite fighting force, heavily armored and mounted, was typically enough to frighten even large numbers of commoners into submission. Not this time. The men and women of the Tuchins were desperate. They had lived in fear of the routiers for decades. Years of heavy taxation had robbed them of everything the routiers had not stolen. They stood together at Béziers, unarmored and armed with whatever they could find with which to fight, as the knights charged. Utterly shocked that the mob had not broken up ahead of the charge, the confused knights were caught up in a mass of people grabbing at them and the reins of their horses. Knights were pulled from their rides or the animals were killed under them. Their helmets were torn off, their eyes stabbed and their heads bashed in with rocks.

The Massacre of Béziers left at least 41 townsmen and three knights dead. It was the beginning of a mass movement unlike anything France had ever seen. There was an explosion of violence against authorities and routiers alike. Organized by a handful of country squires, the Tuchins even attacked some smaller defensive positions held by minor lords or being used as routier headquarters. Screams of "kill the lords" and "kill the rich" became rallying cries at protests in cities and towns. It seemed that a revolution could be underway south of the Tarn.

Naples

By the end of 1381, only a year after the death of Charles V, the first government of the uncles was on the verge of collapse. The Estates-General of Languedoïl had effectively cut off any revenues from the north. The Estates-General of Languedoc could not even call a meeting, as so much of the south was in open revolt and much of the rest was being preyed upon by the routiers, making travel dangerous. The English had retaken control of Saintogne. Northern France was dangerously exposed to attack, as garrisons on the march of Calais and the coast of Normandy were being hollowed out by desertions for lack of pay. The crown was piling up huge debts that it had no ability to repay.

Anjou had no response to the burgeoning crises, as his personal ambitions had already eclipsed his interest in the regency. In 1380, Anjou had been named heir to the childless Queen Giovanna I of Naples, who had been alienated by Pope Urban VI of Rome. As the church was split between two rival popes at the time, Giovanna switched her obedience to Pope Clement VII of Avignon. She was then deposed by her cousin, Carlo of Durazzo, in the first Urbanist crusade. In fall 1381, Anjou came under immense pressure from the Avignon pontiff to lead an expedition to restore the queen of Naples and secure his inheritance. In early 1382, Anjou resigned his position as regent and left Paris to launch a Clementist counter-crusade.

Aftermath

The first government of the uncles was judged to be a failure by contemporaries and most modern historians agree with that verdict. Charles V was considered a great man in his own day, but his greatness came at a terrible cost. Popular anger over taxation and the conduct of the war had been simmering for years. The king, uniquely attuned to the mood of the county, had kept that anger from boiling over. It would have been difficult for anyone to hold France together after his death, but the duke of Anjou was completely unsuited for the role of regent at such a time. Ambitious, imperious, and short-sighted, he often seemed more interested in asserting himself over his brother Burgundy than he did in resolving the problems that faced the country. Burgundy was their father's favorite son, one of their kingly brother's most influential advisors, and set to become the wealthiest man in France, as his wife was the greatest heiress in western Europe. Anjou's jealousy of his younger brother drove his pursuit of the crown of Naples to a point where the regency became more of a distraction than a duty or honor.

Anjou's departure left Burgundy as the dominant force in France, beginning the second government of the uncles. The new regime had to reckon with the financial crisis that Anjou had left in his wake, revolts in Flanders and Languedoc, and the war with England. Anjou's Crusade launched in the spring.

Last edited:

@material_boy ! That was incredible! Hope that Burgundy and his line still Ally With the English and that anjou Will fail again!

Glad you liked it 😊@material_boy ! That was incredible! Hope that Burgundy and his line still Ally With the English and that anjou Will fail again!

Burgundy will get his turn in the spot in "Second Government of the Uncles," which will be up before the end of the month. But first, we'll follow Anjou to Italy in "Anjou's Crusade."

Great, hopefully we will get burgundy making many trades under the table with england (gotta get that english wool) and Anjoue will get crushed in italy.Glad you liked it 😊

Burgundy will get his turn in the spot in "Second Government of the Uncles," which will be up before the end of the month. But first, we'll follow Anjou to Italy in "Anjou's Crusade."

The wool trade will definitely be a consideration in Burgundy's spotlight ...Great, hopefully we will get burgundy making many trades under the table with england (gotta get that english wool) and Anjoue will get crushed in italy.

And naturally HE and his fief will benefit the most.The wool trade will definitely be a consideration in Burgundy's spotlight ...

Very good chapter, France is going through some tough times. Are we gonna see a radical peasant commune rise up in France? I'd love for that to happen, the English need to give support to it.

Parts of the HRE will be touched on briefly, but I don't have plans for anything specifically about it at the moment.@material_boy Will there be a chapter on the HRE at some point?

Good to know - this is such a great TL that anything you write winds up being entertaining.Parts of the HRE will be touched on briefly, but I don't have plans for anything specifically about it at the moment.

Thank you 😅Good to know - this is such a great TL that anything you write winds up being entertaining.

Who knows, it could come into a more prominent role. I didn't expect to spend so much time in Iberia (I had only imagined the "Battle of Estella" and "Lancaster's Crusade" when I started out), so maybe there will be more from the HRE that I just don't see right now.

The good thing is that the dukes had not started to kill each other.

Yet.

Yet.

Last edited:

Neapolitan Crusades

Neapolitan Crusades

The Neapolitan Crusades were a pair of military expeditions approved by Pope Urban VI of Rome and his rival, Pope Clement VII of Avignon, to determine control of the kingdom of Naples. They were a major part of the Western Schism, when the Catholic Church was divided between two popes, and fought during the Hundred Years War between the kingdom of England and the kingdom of France. This eventually led the Urbanist candidate for the Neapolitan throne, Carlo of Durazzo, to forge an alliance with the English, as Clement's candidate was the French prince Louis I, duke of Anjou.

A crusading revival in the mid to late 14th century made Durazzo's Crusade and the counter-crusade led by Louis of Anjou broadly popular in their own time, but Anjou's was condemned by his own brother, the duke of Burgundy, who had been Anjou's rival in France. The split between Anjou and Burgundy led to serious complications for Anjou's Crusade, which was forced to rely almost entirely on Clement VII for funds and materials.

Background

The kingdom of Naples was officially known as the kingdom of Sicily, which had once ruled over both the island of Sicily and more or less the southern half of the Italian peninsula. The old kingdom of Sicily was a papal fief, but a rebellion in the 1280s cleaved the old kingdom in two. This created an insular kingdom that rejected papal overlordship and a peninsular kingdom that continued to recognize papal overlordship. Both kingdoms claimed to be the rightful kingdom of Sicily, though the peninsular kingdom is commonly called Naples, after its capital city, to avoid confusion.

In the early 1380s, Queen Giovanna of Naples was in her mid 50s and childless. Giovanna was generally an attentive and fair ruler who had carefully steered her kingdom back to prosperity after a destructive war with King Louis of Hungary in the 1340s and 50s. Giovanna and Louis were second cousins and rivals. In 1369, they were also both childless. Via primogeniture, the system of inheritance that had led Giovanna herself to the throne, the queen's niece, Margherita of Durazzo, was heiress to the kingdom. Cautiously, Giovanna and Louis negotiated the marriage of their other cousin, Carlo of Durazzo, who was the last male-line member of their family, to Margherita as part of a plan to have the pair eventually succeed to both Hungary and Naples. Then, the following year, their plan for the succession collapsed when Louis's wife gave birth to a daughter after 17 years of childlessness. Two more daughters soon followed. Plans for uniting Hungary and Naples were set aside.

Giovanna felt threatened by the birth of Louis's third daughter. As king of Hungary and Poland, Louis was expected to divide his kingdoms between his two eldest daughters, and Giovanna feared that Louis may invade Naples again to secure an inheritance for the third. Carlo, who had spent years apprenticing for kingship in Hungary, grew concerned that he may inherit nothing at all and began to lobby Giovanna for appointments, land, and recognition as heir. Carlo was a popular figure and skilled warrior, creating fears that he would try to depose Giovanna if she allowed him any real influence in Naples. In time, Carlo was recognized as heir jure uxoris, but denied everything else for which he asked.

Schism

The Western Schism presented yet another threat to Giovanna's reign. The Roman Pope Urban VI was the first Italian pope in generations, and was Neapolitan himself. Giovanna knew him well before his election, but she was among the first major figures Urban would alienate after taking the chair of Saint Peter. He insulted a high-ranking Neapolitan delegation and questioned whether a woman could hold a crown in her own right. Giovanna took this to mean that Urban was considering deposing her. Feeling betrayed by Urban, Giovanna was eventually convinced by legal experts that his election was invalid. She backed the Avignon Pope Clement VII in November 1378.

Giovanna's endorsement of Clement immediately destabilized her reign. The queen had the support of her court, ministers of government, and legal scholars at the university, but the people were shocked that she would abandon the first Italian pope in generations. Riots broke out in the streets of Naples and in other cities and major towns across the country.

In June 1379, Louis of Hungary endorsed Urban VI. At this time, Carlo of Durazzo was at the head of a Hungarian army, skirmishing with the Venetians. Carlo soon became the subject of a plot by Louis of Hungary and Urban VI to unseat Giovanna. As Naples was a papal fief, Urban agreed to depose Giovanna and crown Carlo as the new king. Louis would allow Carlo to lead his Hungarian forces into Italy, and would even provide thousands more, in exchange for Carlo conceding his claim to the crown of Hungary and recognizing Louis's daughters as the rightful heiresses to Louis's territories. Carlo agreed.

Giovanna did not fear the prospect of Carlo's invasion. She believed that she still had enough support in the country and that her husband Otto, duke of Brunswick-Grubenhagen, was a skilled enough commander to turn back Carlo's small army. Clement VII, however, would take no chances. The Avignon pontiff saw the control of Naples as vital to conquering Rome and ending the schism. He looked to France for support. Clement relied on the fact that Naples was a papal fief to take matters into his own hands, as Urban had months earlier. Upon hearing that Clement was negotiating with the French to name Louis I, duke of Anjou, her heir, Giovanna sent her own ambassadors to ensure that the deal did not promise Anjou any authority in Naples before her death. Anjou and Clement sealed an alliance in which the duke agreed to personally defend Giovanna and Naples, should the kingdom come under attack by Urbanists.

On 1 February 1380, Clement VII issued a papal bull declaring Anjou heir to the throne of Naples. Giovanna refused to comment on the matter. Her niece and would-be heiress, Margherita, had been a guest at her court since 1376 and was among those who supported Clement. To all outward appearances, their relationship was warm. Then, on 6 June, Margherita left Naples with her young children and joined her husband in Romagna, where he sat with an army of 7,000. In response, on 29 June, Giovanna proclaimed Anjou heir to the throne. She attempted to negotiate an alliance with Florence, but the city refused to get involved. Carlo reached Rome by the fall and another 1,000 would join him as he wintered there. Soon, Giovanna began to lose confidence that her supporters could defeat such an army.

Durazzo's Crusade

Charles V died on 16 September 1380. He was succeeded by his eldest son, who became King Charles VI of France. As the new king was not yet 12, a regency government was set up with Anjou at its head. His first priority was resolving the French crown's conflict with Brittany, in which his own mother-in-law was a major player. He was then dragged into a major dispute with the Estates-General, creating a financial crisis. It quickly became clear that the Neapolitan alliance to which he was a party was a major distraction.

On 2 June 1381, Carlo was crowned King Carlo III of Sicily and Jerusalem by Urban VI in Rome. Two days later, Giovanna dispatched embassies to Avignon and Paris. Four days after that, Carlo left Rome with at least 8,000 men at his back. Giovanna's husband, Otto of Brunswick, led a Neapolitan army north in the hope of blocking the road to the capital. Outclassed and outnumbered, Otto withdrew to the country once Carlo's army came into sight. Carlo did not even bother to pursue.

On 16 July, Carlo arrived at Naples. Otto did as well, planning to attack the larger invading army as it began its siege, trapping its forces between Otto's men and the city's walls. It was a fine plan, but Otto never had the chance to implement it. On the very night of Carlo's arrival, Urbanists inside Naples rebelled and took control of the city walls, throwing open the gates to Carlo's forces. Otto was locked out. Giovanna would have been safe in the castle for some time, but allowed hundreds of people to join her there for protection against Carlo's forces. It was an act of great generosity and stupidity. Six months of food stores were eaten in a matter of weeks.