You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The American System: A Henry Clay TL

- Thread starter TheHedgehog

- Start date

48. Good Government

48. Good Government

“President Carlisle would have preferred to fill his cabinet with reformist allies. However, the Democratic party was as much the party of Hill and Gorman as it was the party of reform. With an evenly divided Senate, he had to select a cabinet to appease all factions. To Treasury, he appointed his fellow reformist William C. Whitney, despite Whitney’s rivalry with the powerful Hill. The venerable conservative Senator Thomas Bayard of Delaware was appointed as Secretary of State, and another of Hill’s intrastate rivals, Stephen G. Cleveland, was made Attorney General.

However, a number of bosses, or allies of bosses, did receive cabinet posts. John Bratton, ally of Martin Gary and a South Carolina congressman, was appointed as just the second ever Secretary of Agriculture. Richard Coke, who had an iron grip on the Texas Democratic party, was stepping down as governor and President Carlisle appointed him Postmaster General, from which post he could purge the Whigs installed by Houk and give favor to Democrats. This selection met with opposition from many Whigs, but he was confirmed 41-40, with Stevenson stepping in to break the tie.

His fractious cabinet was a sign of the quiet but fierce divisions within the Democratic party, and President Carlisle, aside from overseeing the repeal of the Blaine tariffs, battled with the Jacksonian wing of the party over his refusal to fire Whigs from their civil service jobs without cause. His veto of the Interstate Commerce Act in January 1890, which would have regulated railroads and the rates they charged, proved enormously unpopular and sparked a wave of protests in the west. Then, in February 1890, the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad, already in difficult financial straits, filed for bankruptcy. This resulted in the company’s stocks plummeting, which soon affected other railroad stocks. Meanwhile, a revolution in Argentina that deposed the ruling National Autonomists [1] brought a sudden end to foreign investments, affecting both American and British speculators. This, along with a global decline in the price of various commodities, combined to cause not only a series of failures of railroads, but a general run on the banks. As people began exchanging their paper money for gold, banks started to run out.

By the time Theodore Roosevelt, the President of the National Bank, stepped in to reign in the bank runs, nearly 350 banks [2] had run out of specie and gone under. Though further bleeding was staunched by the Bank, 12,000 businesses failed, and the unemployment rate rose sharply. Amid the worst recession since 1877, the Whigs narrowly retook the House, reversing many of their losses in 1886, and regained a slim majority in the Senate. Just when it looked like the Democrats had returned, a poor economy had swept away their new majorities…”

-From WHITE MAN’S NATION: AMERICA 1881-1973 by Kenneth Thurman, published 2003

Presidential Cabinet of John Carlisle:

Vice President: Adlai E. Stevenson I

Secretary of State: Thomas F. Bayard

Secretary of the Treasury: William C. Whitney

Secretary of War: William H. Barnum

Attorney General: Stephen G. Cleveland

Postmaster General: Richard Coke

Secretary of the Interior: James E. Campbell

Secretary of Agriculture: John Bratton

Secretary of the Navy: John F. Andrew

“In a wide-ranging interview on ABC, one exchange in particular between interviewer Jim Heller and President Charlie Breathitt has received the most attention. When questioned about the introduction of a bill in the House of Representatives that would make voter IDs tax-free, Breathitt declined to state his opinion. “I’d have to see the specifics before I decide whether to sign it or not,” he said, prompting Heller to press him. “Respectfully, Mr. President, the bill has been discussed both in Congress and in the media for the past three days. You don’t have any opinion of it, you haven’t seen even an early draft of it?”

The President responded, saying “I have, Jim. And I still have to talk with my advisors about it, but I do have reservations. I mean, states do have the right to oversee their elections. I don’t think, speaking as a conservative, that the federal government should be stepping in here. It isn’t a poll tax, it’s just voter IDs [3], and if people have to pay two dollars fifty to get one at the post office, I just don’t see why that’s grounds for federal intervention.”

The President’s remarks earned him swift condemnation from many Whigs. Speaker Anna Weitzel (Whig-Wisc.) said in a statement that “A tax on a voter ID required to vote is an indirect poll tax. While I respect President Breathitt, his lack of understanding of this simple fact is deeply concerning. It is vital to our democracy that all Americans have an equal opportunity to vote. The President is, whether knowingly or unknowingly, standing in opposition to this principle.” Speaker Weitzel’s statement was echoed by Senate Majority Leader Heleringer (Whig-Kans.), along with dozens of other Whigs.

President Breathitt’s press secretary, James MacDonald, responded to the uproar during the daily press briefing. “Look, the President believes, strongly believes, that banning states from this policy of taxing voter IDs constitutes federal overreach. I mean, the state has to pay for them somehow. Car taxes pay for people’s drivers licenses, after all. It’s clear that the Whig party doesn’t believe in leaving any issue to the states or to individuals. Just look at the recent Ogallala Aquifer battle – why couldn’t the state of Kansas or the state of Nebraska build the canals themselves? Why did Whig congressional leadership have to threaten a government shutdown in order to secure funding for a boondoggle that the federal government has no business funding? To the President, this voter ID bill is just another instance of the Whig party needlessly expanding the purview of the federal government.”

Senator Thad Marshall (Whig-Neb.) castigated the President during an exchange with reporters on the steps of the capitol. “If the President doesn’t think that taxing voter IDs constitutes a poll tax, then he doesn’t have goddamned clue what a poll tax is. Historically, poll taxes were put in place by Democrat state governments all over the south so that all the poor black people couldn’t vote, if they even made it to the polling station alive. They were used and I guess are still being used, as a method of voter suppression to keep blacks and poor people from voting [4]. Taxing the act of voting hurts poor people way worse than it does the rich, and guess what? Most poor people in this country vote for Whigs, so it’s no wonder why all these Democrat lawmakers support poll taxes.” When asked by a reporter from Century Television, a pro-Democratic news outlet, why he thought a tax on voter IDs was a poll tax, Marshall said “this shouldn’t be so complicated for you people to understand. You need the ID to vote, right? So, if you put a tax on the ID, you need to pay a tax in order to vote. It’s an indirect poll tax, and it’s wrong.”

President Breathitt is no stranger to gaffes and missteps, describing urban Whig voters as “living in crime central” during his 2016 campaign and referring to a Black audience as “you people [5]” during a town hall event in Richmond about his proposed Pan-American Free Trade Agreement (PAFTA) in 2018. This latest incident…”

-From BREATHITT UNDER FIRE OVER POLL TAX GAFFE by Kenny Yates, published on The National Report, June 3rd, 2022

“Coleman Bryant Elkins was born in Ravenna, Ohio, on August 17th, 1842, to Henry Elkins and his wife Elizabeth Pickett. His father was a local attorney who was active in the county Whig party, giving Coleman political exposure from an early age. Ravenna is located in the Western Reserve region of Ohio, one of the most abolitionist regions of the country at the time, and the Elkins family were active in local anti-slavery groups. Coleman attended the Western Reserve College, where he studied law, but interrupted his education to serve in the Ohio state militia during the civil war. Upon returning to Western Reserve, Elkins graduated in 1864 with his law degree. After working in his father’s office for three years, Elkins moved to Morgantown, Virginia, which was beginning to undergo an economic boom.

Elkins joined the firm Waitman T. Willey, a prominent local lawyer and Whig politician. By 1874, records indicate that Elkins had established himself sufficiently as a lawyer that he formed his own practice in Lynchburg, a rapidly growing industrial hub for the steel and coal industries and a city of some 15,000 people. In Lynchburg, Elkins immersed himself in Whig politics and quickly established himself as a well-regarded attorney. His investments in the Appalachian Steel Company and local railroads made him both wealthy and a community leader. He served as a delegate to the 1877 Virginia constitutional convention, where he eloquently argued in favor of abolition. His profile in Lynchburg politics raised, he was selected as the Whig party’s mayoral candidate by acclamation in 1880 and was elected in a landslide.

As Mayor of Lynchburg, Elkins focused on improving the school system and building a streetcar system to reduce street traffic and enable the city’s expansion. The public school system, established in 1878, had low attendance from German American children, as their parents protested the English-only curriculum and chose to send their children to private schools. Seeking to remedy this situation, Elkins proposed introducing select classes taught in both English and German to preserve the language and also learn English. This was narrowly adopted by the city council and proved enormously popular with the city’s German community – their attendance in the public schools skyrocketed. This law introducing bilingualism into public schools was the first of its kind in the country, and would inspire not only municipal laws in Milwaukee, Columbus, Cincinnati, and Louisville, but also statewide laws in Wisconsin, Illinois, and Ohio. His other major accomplishment was chartering the city’s first streetcar company [6], which connected the neighborhoods of the city to the downtown and allowed for the construction of early suburbs. The streetcars eroded the insular nature of Lynchburg’s ethnic neighborhoods, fostering a greater sense of community and civic pride.

While in office, Elkins served as a delegate to the 1884 and 1888 Whig national conventions and argued against the party’s support of English-only laws at the latter. He nevertheless campaigned for Sherman in 1888 and supported the 14th amendment. In 1890, amid the nationwide recession, Elkins was elected to Congress from Lynchburg’s seat by an overwhelming margin. In Congress, he established himself as a supporter of tariffs and naval expansion, frequently echoing Blaine’s view that British investments in central and south America posed a threat to American geopolitical interests in the same regions. By the time 1892 rolled around, he was viewed by some within the party as a potential presidential candidate…”

-From SOBER AND INDUSTRIOUS: A HISTORY OF THE WHIGS by Greg Carey, published 1986

[1] More on Argentina in the next chapter.

[2] OTL, it was more like 500. TTL, the National Bank’s restraining influence on speculation prevents more banks from collapsing, but the recession is still pretty bad.

[3] Some things don’t change in ATLs, I guess.

[4] Another big way that the southern courthouse cliques cling to power is their ruthless suppression of the vote. If the opposition can’t vote, then there isn’t much of an opposition.

[5] In full Ross Perot cosplay.

[6] Lynchburg got streetcars right around this time IOTL, too.

“President Carlisle would have preferred to fill his cabinet with reformist allies. However, the Democratic party was as much the party of Hill and Gorman as it was the party of reform. With an evenly divided Senate, he had to select a cabinet to appease all factions. To Treasury, he appointed his fellow reformist William C. Whitney, despite Whitney’s rivalry with the powerful Hill. The venerable conservative Senator Thomas Bayard of Delaware was appointed as Secretary of State, and another of Hill’s intrastate rivals, Stephen G. Cleveland, was made Attorney General.

However, a number of bosses, or allies of bosses, did receive cabinet posts. John Bratton, ally of Martin Gary and a South Carolina congressman, was appointed as just the second ever Secretary of Agriculture. Richard Coke, who had an iron grip on the Texas Democratic party, was stepping down as governor and President Carlisle appointed him Postmaster General, from which post he could purge the Whigs installed by Houk and give favor to Democrats. This selection met with opposition from many Whigs, but he was confirmed 41-40, with Stevenson stepping in to break the tie.

His fractious cabinet was a sign of the quiet but fierce divisions within the Democratic party, and President Carlisle, aside from overseeing the repeal of the Blaine tariffs, battled with the Jacksonian wing of the party over his refusal to fire Whigs from their civil service jobs without cause. His veto of the Interstate Commerce Act in January 1890, which would have regulated railroads and the rates they charged, proved enormously unpopular and sparked a wave of protests in the west. Then, in February 1890, the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad, already in difficult financial straits, filed for bankruptcy. This resulted in the company’s stocks plummeting, which soon affected other railroad stocks. Meanwhile, a revolution in Argentina that deposed the ruling National Autonomists [1] brought a sudden end to foreign investments, affecting both American and British speculators. This, along with a global decline in the price of various commodities, combined to cause not only a series of failures of railroads, but a general run on the banks. As people began exchanging their paper money for gold, banks started to run out.

By the time Theodore Roosevelt, the President of the National Bank, stepped in to reign in the bank runs, nearly 350 banks [2] had run out of specie and gone under. Though further bleeding was staunched by the Bank, 12,000 businesses failed, and the unemployment rate rose sharply. Amid the worst recession since 1877, the Whigs narrowly retook the House, reversing many of their losses in 1886, and regained a slim majority in the Senate. Just when it looked like the Democrats had returned, a poor economy had swept away their new majorities…”

-From WHITE MAN’S NATION: AMERICA 1881-1973 by Kenneth Thurman, published 2003

Presidential Cabinet of John Carlisle:

Vice President: Adlai E. Stevenson I

Secretary of State: Thomas F. Bayard

Secretary of the Treasury: William C. Whitney

Secretary of War: William H. Barnum

Attorney General: Stephen G. Cleveland

Postmaster General: Richard Coke

Secretary of the Interior: James E. Campbell

Secretary of Agriculture: John Bratton

Secretary of the Navy: John F. Andrew

“In a wide-ranging interview on ABC, one exchange in particular between interviewer Jim Heller and President Charlie Breathitt has received the most attention. When questioned about the introduction of a bill in the House of Representatives that would make voter IDs tax-free, Breathitt declined to state his opinion. “I’d have to see the specifics before I decide whether to sign it or not,” he said, prompting Heller to press him. “Respectfully, Mr. President, the bill has been discussed both in Congress and in the media for the past three days. You don’t have any opinion of it, you haven’t seen even an early draft of it?”

The President responded, saying “I have, Jim. And I still have to talk with my advisors about it, but I do have reservations. I mean, states do have the right to oversee their elections. I don’t think, speaking as a conservative, that the federal government should be stepping in here. It isn’t a poll tax, it’s just voter IDs [3], and if people have to pay two dollars fifty to get one at the post office, I just don’t see why that’s grounds for federal intervention.”

The President’s remarks earned him swift condemnation from many Whigs. Speaker Anna Weitzel (Whig-Wisc.) said in a statement that “A tax on a voter ID required to vote is an indirect poll tax. While I respect President Breathitt, his lack of understanding of this simple fact is deeply concerning. It is vital to our democracy that all Americans have an equal opportunity to vote. The President is, whether knowingly or unknowingly, standing in opposition to this principle.” Speaker Weitzel’s statement was echoed by Senate Majority Leader Heleringer (Whig-Kans.), along with dozens of other Whigs.

President Breathitt’s press secretary, James MacDonald, responded to the uproar during the daily press briefing. “Look, the President believes, strongly believes, that banning states from this policy of taxing voter IDs constitutes federal overreach. I mean, the state has to pay for them somehow. Car taxes pay for people’s drivers licenses, after all. It’s clear that the Whig party doesn’t believe in leaving any issue to the states or to individuals. Just look at the recent Ogallala Aquifer battle – why couldn’t the state of Kansas or the state of Nebraska build the canals themselves? Why did Whig congressional leadership have to threaten a government shutdown in order to secure funding for a boondoggle that the federal government has no business funding? To the President, this voter ID bill is just another instance of the Whig party needlessly expanding the purview of the federal government.”

Senator Thad Marshall (Whig-Neb.) castigated the President during an exchange with reporters on the steps of the capitol. “If the President doesn’t think that taxing voter IDs constitutes a poll tax, then he doesn’t have goddamned clue what a poll tax is. Historically, poll taxes were put in place by Democrat state governments all over the south so that all the poor black people couldn’t vote, if they even made it to the polling station alive. They were used and I guess are still being used, as a method of voter suppression to keep blacks and poor people from voting [4]. Taxing the act of voting hurts poor people way worse than it does the rich, and guess what? Most poor people in this country vote for Whigs, so it’s no wonder why all these Democrat lawmakers support poll taxes.” When asked by a reporter from Century Television, a pro-Democratic news outlet, why he thought a tax on voter IDs was a poll tax, Marshall said “this shouldn’t be so complicated for you people to understand. You need the ID to vote, right? So, if you put a tax on the ID, you need to pay a tax in order to vote. It’s an indirect poll tax, and it’s wrong.”

President Breathitt is no stranger to gaffes and missteps, describing urban Whig voters as “living in crime central” during his 2016 campaign and referring to a Black audience as “you people [5]” during a town hall event in Richmond about his proposed Pan-American Free Trade Agreement (PAFTA) in 2018. This latest incident…”

-From BREATHITT UNDER FIRE OVER POLL TAX GAFFE by Kenny Yates, published on The National Report, June 3rd, 2022

“Coleman Bryant Elkins was born in Ravenna, Ohio, on August 17th, 1842, to Henry Elkins and his wife Elizabeth Pickett. His father was a local attorney who was active in the county Whig party, giving Coleman political exposure from an early age. Ravenna is located in the Western Reserve region of Ohio, one of the most abolitionist regions of the country at the time, and the Elkins family were active in local anti-slavery groups. Coleman attended the Western Reserve College, where he studied law, but interrupted his education to serve in the Ohio state militia during the civil war. Upon returning to Western Reserve, Elkins graduated in 1864 with his law degree. After working in his father’s office for three years, Elkins moved to Morgantown, Virginia, which was beginning to undergo an economic boom.

Elkins joined the firm Waitman T. Willey, a prominent local lawyer and Whig politician. By 1874, records indicate that Elkins had established himself sufficiently as a lawyer that he formed his own practice in Lynchburg, a rapidly growing industrial hub for the steel and coal industries and a city of some 15,000 people. In Lynchburg, Elkins immersed himself in Whig politics and quickly established himself as a well-regarded attorney. His investments in the Appalachian Steel Company and local railroads made him both wealthy and a community leader. He served as a delegate to the 1877 Virginia constitutional convention, where he eloquently argued in favor of abolition. His profile in Lynchburg politics raised, he was selected as the Whig party’s mayoral candidate by acclamation in 1880 and was elected in a landslide.

As Mayor of Lynchburg, Elkins focused on improving the school system and building a streetcar system to reduce street traffic and enable the city’s expansion. The public school system, established in 1878, had low attendance from German American children, as their parents protested the English-only curriculum and chose to send their children to private schools. Seeking to remedy this situation, Elkins proposed introducing select classes taught in both English and German to preserve the language and also learn English. This was narrowly adopted by the city council and proved enormously popular with the city’s German community – their attendance in the public schools skyrocketed. This law introducing bilingualism into public schools was the first of its kind in the country, and would inspire not only municipal laws in Milwaukee, Columbus, Cincinnati, and Louisville, but also statewide laws in Wisconsin, Illinois, and Ohio. His other major accomplishment was chartering the city’s first streetcar company [6], which connected the neighborhoods of the city to the downtown and allowed for the construction of early suburbs. The streetcars eroded the insular nature of Lynchburg’s ethnic neighborhoods, fostering a greater sense of community and civic pride.

While in office, Elkins served as a delegate to the 1884 and 1888 Whig national conventions and argued against the party’s support of English-only laws at the latter. He nevertheless campaigned for Sherman in 1888 and supported the 14th amendment. In 1890, amid the nationwide recession, Elkins was elected to Congress from Lynchburg’s seat by an overwhelming margin. In Congress, he established himself as a supporter of tariffs and naval expansion, frequently echoing Blaine’s view that British investments in central and south America posed a threat to American geopolitical interests in the same regions. By the time 1892 rolled around, he was viewed by some within the party as a potential presidential candidate…”

-From SOBER AND INDUSTRIOUS: A HISTORY OF THE WHIGS by Greg Carey, published 1986

[1] More on Argentina in the next chapter.

[2] OTL, it was more like 500. TTL, the National Bank’s restraining influence on speculation prevents more banks from collapsing, but the recession is still pretty bad.

[3] Some things don’t change in ATLs, I guess.

[4] Another big way that the southern courthouse cliques cling to power is their ruthless suppression of the vote. If the opposition can’t vote, then there isn’t much of an opposition.

[5] In full Ross Perot cosplay.

[6] Lynchburg got streetcars right around this time IOTL, too.

Thanks! I'll be introducing more fictional characters in the coming chapters, including a couple future presidents...Thanks for the multiple great updates! I’m interested to see how this timeline develops fictional characters as the butterflies keep flapping.

What did VP Harlan get up to? I see he didn't enter into the 1888 contest, so has he just retired from politics?

(Also, two full updates and a wiki box? You spoil us !)

!)

(Also, two full updates and a wiki box? You spoil us

Harlan just kinda retired, yeah. He might return to state politics or practicing law, but he was never a major part of the Blaine administration.What did VP Harlan get up to? I see he didn't enter into the 1888 contest, so has he just retired from politics?

(Also, two full updates and a wiki box? You spoil us!)

Thanks! I aim to please

49. Revolution and Recession

49. Revolution and Recession

“After emerging victorious from the Atacama War in 1881, Argentina entered a period of great prosperity, helped by the arrival of large numbers of Sicilian and Irish immigrants. Under the rule of the corrupt and oligarchic National Autonomist Party and fueled by a deluge of foreign investments, the country shifted towards industrial agriculture, though the industrialization of later decades had yet to happen. Amid the economic boom, the NAP instituted universal, free, secular education to all children in 1884, and entered into a naval arms race with Brazil [1].

This era of economic expansion came to an end as a series of large corporations went bankrupt towards the end of 1888, causing foreign investment to slow. This, combined with the rise of inflation, caused the speculative bubble in Argentina to burst, and the country entered a deep recession by mid-1889 (that helped cause a global economic slowdown the following year). The working class (many of its members having arrived during the boom years of the 1880s) had begun to organize before the Depression of 1889, and as businesses closed and companies made cutbacks, waves of strikes rocked the cities. President Miguel Celman was incredibly unpopular, and the Civic Union, led by Leandro Alem and Aristobulo del Valle, plotted to oust him. They counted on the indirect support of former President Bartolome Mitre.

The Civic Union secured the support of several army units in Buenos Aires, and Leandro Alem was able to secure the support of most of the expanded navy, as well. Manuel Campos, the leader of the rebel forces, planned to first seize the Artillery Park and establish a revolutionary junta, then secure key government buildings and capture the President and his cabinet, as well as Julio Roca, the President of the Senate and powerful former President. Meanwhile, the navy would simultaneously bombard the Casa Rosada barracks to cripple the ability of government troops to respond. After narrowly evading arrest by the government [2], Campos initiated the coup d’état on July 26th, as planned.

The rebel forces quickly secured Artillery Park, while the fleet bombarded the barracks and caught the government troops unawares [3]. Campo, following the plan [4], moved his well-armed [5] troops out of the park and towards the key objectives. Within six hours of the coup’s beginning, militiamen had arrested President Celman, Vice President Pellegrini, War Minister Levalle, and Senate President Roca. Meanwhile, after fighting their way through the streets, other rebel forces captured the barracks, which had been heavily bombarded by the navy. The remaining government troops surrendered after a brief battle. With much of the executive branch captured and the government troops in the city either captured or in disarray, the remaining resistance to the Civic Union (mostly Buenos Aires police officers) dissipated by the end of the 27th.

From the junta’s provisional headquarters on the Artillery Park, Alem issued the August Declaration, a manifesto of the Civic Union’s aims for the revolution. They had acted to “avoid the ruin of the country” by deposing a “corrupt government that represents illegality and corruption.” The junta condemned the “credo of the government that forces the people to live without voice or vote, witness the disappearance of rules, the trampling of principles and guarantees, tolerate the usurpation of our political rights, and maintaining those in power who have wrought the disgrace of the republic [6].”

There was some resistance from the provinces, but the swift decapitation of the central government and the beginning of insurrections in Corrientes and Tucuman pressured the other provinces to fall in line behind the new Revolutionary Junta, with Leandro Alem as its provisional president. By the end of August, the situation had calmed and Alem called for general elections to take place in April the following year, with secret ballots and universal male suffrage. It was here that the Civic Union split, between Alem’s more radical followers and Mitre’s more conservative followers. Julio Roca, disappointed that the entire system of patronage he had built had been swept away, nevertheless attempted to hold together the NAP and put forth the moderate Roque Saenz Pena as the party’s candidate.

The election was held in April under the terms of Alem’s August Declaration, though the electoral college remained in place. Alem received the unanimous nomination of the Radical Civic Union, and Mitre and Saenz Pena were also unanimously nominated by their respective parties. While Mitre’s National Civic Union was a cohesive party, the National Autonomists splintered into regionalist factions, with the Cordoba faction forming its own party and running Governor Manuel Pizarro, and the Corrientes faction running former Governor Juan Ramon Vidal. The Socialists nominated their leader Juan Justo, but the party was still weak nationally, and most workers gravitated towards the Radical Civic Union.

On election day Alem won a slim plurality of the popular vote, edging out Mitre by 6 percentage points. The National Autonomists completely collapsed, as Saenz Pena, despite his moderation, was unable to overcome his ties to the deposed Celman presidency or win back the Cordoba and Corrientes splinter tickets. When the electoral college met in July, just under a year since the Revolution of the Park, Leandro Alem was elected President with 120 electoral votes out of 232, with Mitre in a distant second with 52 and Saenz Pena third with 49. Regionalist parties and faithless electors comprised the rest. In the concurrent legislative elections, the entire Chamber of Deputies was put up for election. Ordinarily, half of the chamber stood for election every two years, but Alem, Mitre, and the Revolutionary Junta agreed that a truly fresh start mandated fresh elections for the entire chamber. The Radical Civic Union won a plurality of seats, with 44 out of 120. The National Autonomists came in second with 33, and the National Civic Union was the third-largest party with 25 seats. The two Civic Unions formed a cautious coalition to ward off the conservative parties.

President Alem and his allies quickly cemented the promised reforms, passing labor protections, legalizing trade unions, and working to diversify the national economy away from agriculture and towards other forms of industry. Argentina began its first steps towards the powerful liberal democracy it is today…”

-From ARGENTINA: A MODERN HISTORY by Jessica Harvey, published 2011

“Amid the devastating recession, there was a resultant reduction in purchases of consumer goods and raw materials. Therefore, rail traffic declined, and railroad companies began laying off workers and cutting wages. In Saint Louis, wage cuts at the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad depot without cuts in prices at the company store sparked protests, and the (un-unionized) workers called for a strike, which began on April 17th, 1891.

With the strike underway, many workers at the depot joined the Federation of Trade Unions [7], which supported the strike by launching sympathy strikes at railroad stations where workers refused to handle B&O rolling stock or service B&O locomotives. Within days, rail traffic at not only the Saint Louis B&O depot, but the Saint Louis Union Station and freight depots in Chicago, Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, Richmond, and Philadelphia had shut down. The B&O and other railroads affected by the work stoppages began hiring strikebreakers, who were in ample supply due to the high unemployment rate. The strikers often shouted insults and threw rocks as the strikebreakers headed to work, and finally, on May 3rd, violence broke out as strikers began beating strikebreakers in order to prevent them from entering the B&O depot. The brawl escalated into a riot as strikers destroyed locomotives and rolling stock and set fire to nearby buildings.

…strike threatened economic pandemonium if it became a protracted affair. President Carlisle agreed with his cabinet that the strike had to be ended swiftly, and he directed Attorney General Cleveland to obtain an injunction ordering the end of the strikes. This was duly granted by the local circuit court, and Cleveland warned the FTU that they were prohibited from “compelling or encouraging any impacted railroad employee to refuse to perform or hinder the performance of any of their duties.” This was ignored by the FTU, which was determined to make a strong statement and demonstrate its power and dedication to the railroad executives. An attempt by a more radical union, the Brotherhood of International Workers [8], to start a nationwide general strike, was opposed by the FTU and the tension ratcheted. Finally, on May 23rd, federal army troops and the Missouri National Guard moved in to suppress the strike. While the more moderate FTU stood down and urged the preservation of peace, the BIW-affiliated workers were often belligerent, leading to the deaths of 31 railroad workers nationwide. Property damage exceeded $90 million.

Carlisle claimed that his actions were constitutionally required because the railroad stoppages threatened the transport of mail, and the public generally agreed. However, while he won praise for his firm, decisive response to the railroad strikes, it did little to salvage his popularity as the country remained mired in the worst recession since 1837.”

-From LONG VIOLENT HISTORY: THE STRUGGLE OF AMERICA’S UNIONS by Jennifer White, published 2018

“It is difficult to argue that Carlisle was unaware of his crippling unpopularity, but perhaps he simply wouldn’t let himself believe it. The President decided to visit his hometown of Covington in June of 1891, partly to escape from the tension in Washington and partly to campaign for John Y. Brown, the Democratic nominee for Governor of Kentucky. His reception was cool, even in his hometown, and the President was dejected as he walked to his home after being booed at a speech [9].

When a young man called out to him and exclaimed “Mr. President! What an honor would be to shake your hand, sir,” Carlisle turned toward him and smiled, extending his hand. However, Henry Jennings did not intend to shake the President’s hand – he had been laid off from his job at the Stewart Iron Works due to the depression and blamed the President for it. Having already struggled with mental problems and alcoholism, the loss of his job untethered Jennings and sent him into a spiral, and when he heard that Carlisle was coming to visit Covington, he resolved to assassinate him.

Thus, when Carlisle turned to shake hands with Jennings, he was instead met with the barrel of a pistol. Jennings fired three times at close range, striking the President in the lung once and stomach twice. The wounded president was carried by his escorts back to his residence as Jennings was subdued and arrested by a policeman who had come running at the sound of gunfire. Despite the attention of doctors, President John Carlisle contracted sepsis within days and died on June 19th, six days after being shot. Upon being told of the President’s death, Vice President Stevenson ordered a national period of mourning and declared himself the President, not acting-President as some in his cabinet urged him to do [10]. Many Whigs resisted Stevenson’s full assumption of the Presidency, and within weeks the Whig majority in Congress began debating legislation to refer to Stevenson strictly as Vice President-acting President. It seemed that not only was the United States mired in an economic crisis, but it was also mired in a constitutional crisis as well…”

-From WHITE MAN’S NATION: AMERICA 1881-1973 by Kenneth Thurman, published 2003

[1] OTL, the arms race was with Chile. TTL, with a weaker Chile and greater tensions with Brazil, that’s who Argentina has the arms race with.

[2] This happened OTL, and it may have led to Campo turning traitor and collaborating with Roca instead.

[3] TTL, the government doesn’t find out about the coup and so their troops aren’t prepared. Meanwhile, the rebel takeover of the fleet goes a lot smoother.

[4] OTL, Campo refused to leave the park, ceding the initiative to the government. It is unknown why he did it.

[5] From the Civic Union’s OTL 1890 manifesto.

[6] OTL, the rebels found they had half as much ammunition as they thought. TTL, they double check and are properly armed.

[7] Basically a more successful and cohesive AFL.

[8] Basically a more isolated and radical ARU.

[9] This happened to Carlisle in 1896 IOTL. Not the assassination attempt, obviously.

[10] Remember that ITTL, Carlisle is the first president to die in office. The exact role of the Vice President is still unsure.

“After emerging victorious from the Atacama War in 1881, Argentina entered a period of great prosperity, helped by the arrival of large numbers of Sicilian and Irish immigrants. Under the rule of the corrupt and oligarchic National Autonomist Party and fueled by a deluge of foreign investments, the country shifted towards industrial agriculture, though the industrialization of later decades had yet to happen. Amid the economic boom, the NAP instituted universal, free, secular education to all children in 1884, and entered into a naval arms race with Brazil [1].

This era of economic expansion came to an end as a series of large corporations went bankrupt towards the end of 1888, causing foreign investment to slow. This, combined with the rise of inflation, caused the speculative bubble in Argentina to burst, and the country entered a deep recession by mid-1889 (that helped cause a global economic slowdown the following year). The working class (many of its members having arrived during the boom years of the 1880s) had begun to organize before the Depression of 1889, and as businesses closed and companies made cutbacks, waves of strikes rocked the cities. President Miguel Celman was incredibly unpopular, and the Civic Union, led by Leandro Alem and Aristobulo del Valle, plotted to oust him. They counted on the indirect support of former President Bartolome Mitre.

The Civic Union secured the support of several army units in Buenos Aires, and Leandro Alem was able to secure the support of most of the expanded navy, as well. Manuel Campos, the leader of the rebel forces, planned to first seize the Artillery Park and establish a revolutionary junta, then secure key government buildings and capture the President and his cabinet, as well as Julio Roca, the President of the Senate and powerful former President. Meanwhile, the navy would simultaneously bombard the Casa Rosada barracks to cripple the ability of government troops to respond. After narrowly evading arrest by the government [2], Campos initiated the coup d’état on July 26th, as planned.

The rebel forces quickly secured Artillery Park, while the fleet bombarded the barracks and caught the government troops unawares [3]. Campo, following the plan [4], moved his well-armed [5] troops out of the park and towards the key objectives. Within six hours of the coup’s beginning, militiamen had arrested President Celman, Vice President Pellegrini, War Minister Levalle, and Senate President Roca. Meanwhile, after fighting their way through the streets, other rebel forces captured the barracks, which had been heavily bombarded by the navy. The remaining government troops surrendered after a brief battle. With much of the executive branch captured and the government troops in the city either captured or in disarray, the remaining resistance to the Civic Union (mostly Buenos Aires police officers) dissipated by the end of the 27th.

From the junta’s provisional headquarters on the Artillery Park, Alem issued the August Declaration, a manifesto of the Civic Union’s aims for the revolution. They had acted to “avoid the ruin of the country” by deposing a “corrupt government that represents illegality and corruption.” The junta condemned the “credo of the government that forces the people to live without voice or vote, witness the disappearance of rules, the trampling of principles and guarantees, tolerate the usurpation of our political rights, and maintaining those in power who have wrought the disgrace of the republic [6].”

There was some resistance from the provinces, but the swift decapitation of the central government and the beginning of insurrections in Corrientes and Tucuman pressured the other provinces to fall in line behind the new Revolutionary Junta, with Leandro Alem as its provisional president. By the end of August, the situation had calmed and Alem called for general elections to take place in April the following year, with secret ballots and universal male suffrage. It was here that the Civic Union split, between Alem’s more radical followers and Mitre’s more conservative followers. Julio Roca, disappointed that the entire system of patronage he had built had been swept away, nevertheless attempted to hold together the NAP and put forth the moderate Roque Saenz Pena as the party’s candidate.

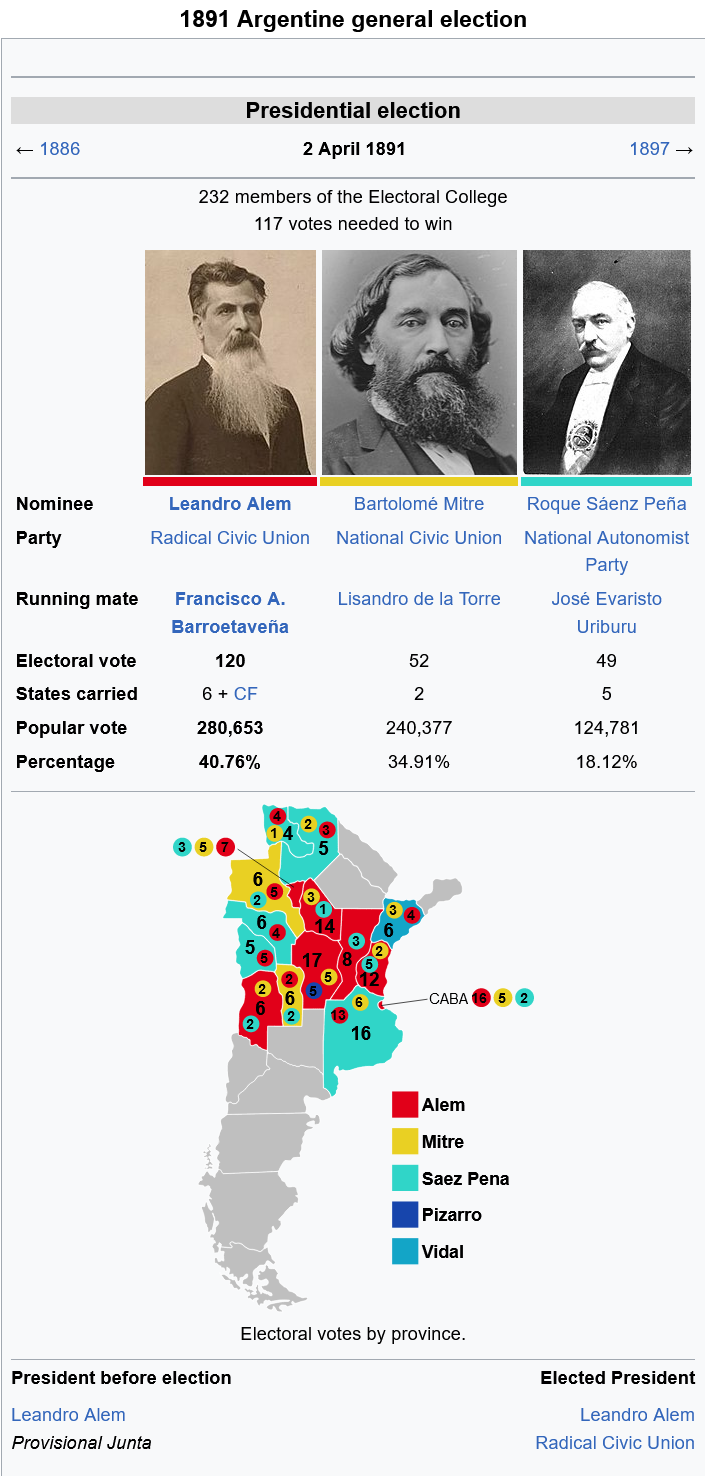

The election was held in April under the terms of Alem’s August Declaration, though the electoral college remained in place. Alem received the unanimous nomination of the Radical Civic Union, and Mitre and Saenz Pena were also unanimously nominated by their respective parties. While Mitre’s National Civic Union was a cohesive party, the National Autonomists splintered into regionalist factions, with the Cordoba faction forming its own party and running Governor Manuel Pizarro, and the Corrientes faction running former Governor Juan Ramon Vidal. The Socialists nominated their leader Juan Justo, but the party was still weak nationally, and most workers gravitated towards the Radical Civic Union.

On election day Alem won a slim plurality of the popular vote, edging out Mitre by 6 percentage points. The National Autonomists completely collapsed, as Saenz Pena, despite his moderation, was unable to overcome his ties to the deposed Celman presidency or win back the Cordoba and Corrientes splinter tickets. When the electoral college met in July, just under a year since the Revolution of the Park, Leandro Alem was elected President with 120 electoral votes out of 232, with Mitre in a distant second with 52 and Saenz Pena third with 49. Regionalist parties and faithless electors comprised the rest. In the concurrent legislative elections, the entire Chamber of Deputies was put up for election. Ordinarily, half of the chamber stood for election every two years, but Alem, Mitre, and the Revolutionary Junta agreed that a truly fresh start mandated fresh elections for the entire chamber. The Radical Civic Union won a plurality of seats, with 44 out of 120. The National Autonomists came in second with 33, and the National Civic Union was the third-largest party with 25 seats. The two Civic Unions formed a cautious coalition to ward off the conservative parties.

President Alem and his allies quickly cemented the promised reforms, passing labor protections, legalizing trade unions, and working to diversify the national economy away from agriculture and towards other forms of industry. Argentina began its first steps towards the powerful liberal democracy it is today…”

-From ARGENTINA: A MODERN HISTORY by Jessica Harvey, published 2011

“Amid the devastating recession, there was a resultant reduction in purchases of consumer goods and raw materials. Therefore, rail traffic declined, and railroad companies began laying off workers and cutting wages. In Saint Louis, wage cuts at the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad depot without cuts in prices at the company store sparked protests, and the (un-unionized) workers called for a strike, which began on April 17th, 1891.

With the strike underway, many workers at the depot joined the Federation of Trade Unions [7], which supported the strike by launching sympathy strikes at railroad stations where workers refused to handle B&O rolling stock or service B&O locomotives. Within days, rail traffic at not only the Saint Louis B&O depot, but the Saint Louis Union Station and freight depots in Chicago, Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, Richmond, and Philadelphia had shut down. The B&O and other railroads affected by the work stoppages began hiring strikebreakers, who were in ample supply due to the high unemployment rate. The strikers often shouted insults and threw rocks as the strikebreakers headed to work, and finally, on May 3rd, violence broke out as strikers began beating strikebreakers in order to prevent them from entering the B&O depot. The brawl escalated into a riot as strikers destroyed locomotives and rolling stock and set fire to nearby buildings.

…strike threatened economic pandemonium if it became a protracted affair. President Carlisle agreed with his cabinet that the strike had to be ended swiftly, and he directed Attorney General Cleveland to obtain an injunction ordering the end of the strikes. This was duly granted by the local circuit court, and Cleveland warned the FTU that they were prohibited from “compelling or encouraging any impacted railroad employee to refuse to perform or hinder the performance of any of their duties.” This was ignored by the FTU, which was determined to make a strong statement and demonstrate its power and dedication to the railroad executives. An attempt by a more radical union, the Brotherhood of International Workers [8], to start a nationwide general strike, was opposed by the FTU and the tension ratcheted. Finally, on May 23rd, federal army troops and the Missouri National Guard moved in to suppress the strike. While the more moderate FTU stood down and urged the preservation of peace, the BIW-affiliated workers were often belligerent, leading to the deaths of 31 railroad workers nationwide. Property damage exceeded $90 million.

Carlisle claimed that his actions were constitutionally required because the railroad stoppages threatened the transport of mail, and the public generally agreed. However, while he won praise for his firm, decisive response to the railroad strikes, it did little to salvage his popularity as the country remained mired in the worst recession since 1837.”

-From LONG VIOLENT HISTORY: THE STRUGGLE OF AMERICA’S UNIONS by Jennifer White, published 2018

“It is difficult to argue that Carlisle was unaware of his crippling unpopularity, but perhaps he simply wouldn’t let himself believe it. The President decided to visit his hometown of Covington in June of 1891, partly to escape from the tension in Washington and partly to campaign for John Y. Brown, the Democratic nominee for Governor of Kentucky. His reception was cool, even in his hometown, and the President was dejected as he walked to his home after being booed at a speech [9].

When a young man called out to him and exclaimed “Mr. President! What an honor would be to shake your hand, sir,” Carlisle turned toward him and smiled, extending his hand. However, Henry Jennings did not intend to shake the President’s hand – he had been laid off from his job at the Stewart Iron Works due to the depression and blamed the President for it. Having already struggled with mental problems and alcoholism, the loss of his job untethered Jennings and sent him into a spiral, and when he heard that Carlisle was coming to visit Covington, he resolved to assassinate him.

Thus, when Carlisle turned to shake hands with Jennings, he was instead met with the barrel of a pistol. Jennings fired three times at close range, striking the President in the lung once and stomach twice. The wounded president was carried by his escorts back to his residence as Jennings was subdued and arrested by a policeman who had come running at the sound of gunfire. Despite the attention of doctors, President John Carlisle contracted sepsis within days and died on June 19th, six days after being shot. Upon being told of the President’s death, Vice President Stevenson ordered a national period of mourning and declared himself the President, not acting-President as some in his cabinet urged him to do [10]. Many Whigs resisted Stevenson’s full assumption of the Presidency, and within weeks the Whig majority in Congress began debating legislation to refer to Stevenson strictly as Vice President-acting President. It seemed that not only was the United States mired in an economic crisis, but it was also mired in a constitutional crisis as well…”

-From WHITE MAN’S NATION: AMERICA 1881-1973 by Kenneth Thurman, published 2003

[1] OTL, the arms race was with Chile. TTL, with a weaker Chile and greater tensions with Brazil, that’s who Argentina has the arms race with.

[2] This happened OTL, and it may have led to Campo turning traitor and collaborating with Roca instead.

[3] TTL, the government doesn’t find out about the coup and so their troops aren’t prepared. Meanwhile, the rebel takeover of the fleet goes a lot smoother.

[4] OTL, Campo refused to leave the park, ceding the initiative to the government. It is unknown why he did it.

[5] From the Civic Union’s OTL 1890 manifesto.

[6] OTL, the rebels found they had half as much ammunition as they thought. TTL, they double check and are properly armed.

[7] Basically a more successful and cohesive AFL.

[8] Basically a more isolated and radical ARU.

[9] This happened to Carlisle in 1896 IOTL. Not the assassination attempt, obviously.

[10] Remember that ITTL, Carlisle is the first president to die in office. The exact role of the Vice President is still unsure.

Last edited:

Ayyy I do like a timeline that incorporates a successful Revolution of the Park and living Leandro Alem as an Argentina POD 😉 good stuff!

Thanks! I’ve been planning this part for a couple months now, so expect an increased focus on Argentina and the ratcheting tensions with Brazil.Ayyy I do like a timeline that incorporates a successful Revolution of the Park and living Leandro Alem as an Argentina POD 😉 good stuff!

Awesome. Excited to see where you go with thatThanks! I’ve been planning this part for a couple months now, so expect an increased focus on Argentina and the ratcheting tensions with Brazil.

The 1891 Argentine Presidential election:

(Man, laying out all the electors was a pain)

(Man, laying out all the electors was a pain)

Last edited:

Was SoS for a while and then a SCoTUS Justice I think?I may have missed out on something, but whatever happened to Lincoln?

I may have missed out on something, but whatever happened to Lincoln?

He was SoS under Cox. After Cox's loss, Lincoln returned to private practice in Illinois, but often campaigned for Whig candidates until his death in 1881.Was SoS for a while and then a SCoTUS Justice I think?

Thanks! It was surprisingly easy to trace the map on inkscape, I must say.I like the alternate borders for Argentina.

Lincoln was a socialist fun fact, is socialism stronger in this alternate America?He was SoS under Cox. After Cox's loss, Lincoln returned to private practice in Illinois, but often campaigned for Whig candidates until his death in 1881.

I hardly think that corresponding with Marx and making a few statements on the codependency between Capital and Labor makes one a socialist, but to answer your question socialism is about as strong in America TTL as it was OTL.Lincoln was a socialist fun fact, is socialism stronger in this alternate America?

I wonder how influential Eugene V. Debbs is going to be like in this timeline.I hardly think that corresponding with Marx and making a few statements on the codependency between Capital and Labor makes one a socialist, but to answer your question socialism is about as strong in America TTL as it was OTL.

Debs specifically doesn’t exist because he was born 15 years after the POD, but the TTL Brotherhood of International Workers is based on his union from the OTL Pullman strike.I wonder how influential Eugene V. Debbs is going to be like in this timeline.

There wont be one major socialist figure TTL, so the socialist movement will be pretty different

Share: