The More Things Change, The More They Stay The Same (1971-72)

"This is the big one!"

- Fred Sanford, "Sanford and Son"

The 1971-72 season was the first of the "Modern TV" era, though several later analysts would, with characteristic pretentiousness, describe this period in television as subsumed within the greater "New Hollywood" movement; but this would be an overly simplistic generalization. Certainly, the continued presence of the Standards & Practices departments at all three commercial networks, coupled with strong regulations by the FCC, prevented the spread of explicit sexual content and violence from the big screen to the small one. For example, "porno chic", a movement which was on the rise in American cinema at the time, would have no equivalent in television. Even the most controversial show on the air, Those Were the Days, didn't dare show their characters moving beyond first base. Furthermore, producers still lacked the creative freedom enjoyed by filmmakers, and were tethered to strict budgets and tough scheduling deadlines. Some of the studios were more indulgent than others, but there was still a tremendous difference between how they handled weekly series and how they handled major motion pictures. It was no coincidence that the most indulgent studio wasn't even in the movie business.

The three commercial networks were forced to adapt to the new twenty-one hour primetime schedules, and some of them were coping better than others. CBS, despite having cancelled nearly two-fifths of their 1970-71 lineup, seemed to be taking it the best, though any potentially dissenting voices were tightly muzzled by Fred Silverman, who took to describing his leaner, meaner network as "a new CBS for a new era of television", helping to cement the idea of a dividing line between "Classic TV" and "Modern TV" within the industry.

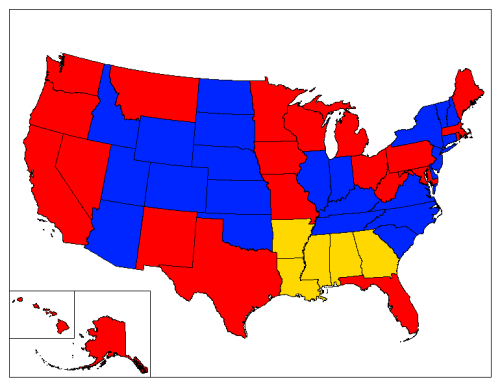

NBC executives found themselves torn. They had 11 Top 30 hits for the season, more than any other network; [1] but their programming choices were, to say the least, erratic. All three of their major Westerns (which, by the early 1970s, were considered a "dinosaur" genre) remained on the air, but at the same time, they carried the most racially diverse lineup on television. Their top-rated show (ranked #2 overall in both 1970-71 and 1971-72) was a variety program starring a black comedian, Flip Wilson; he was described by Time Magazine, in their January 31, 1972 issue, as "TV's First Black Superstar". This designation was playfully challenged by Bill Cosby, a frequent guest on Wilson's show, who also starred on an eponymous series (a sitcom) [2] on NBC, resulting in the famous "Battle of the Superstars" sketch. Many observers noted that, although there had been no black performers in recurring, non-stereotypical roles on television just seven years before, now there were two big TV stars, both of whom were very popular with white audiences. And this disregarded the other shows on NBC with black leads: "Julia", starring Diahann Carroll [3], and, partway through the season, a new series with a largely black cast: "Sanford and Son". It starred another black comedian, Redd Foxx, and also gained traction with white audiences, becoming the highest-rated new show of the year. Indeed, even a program with the racial composition of Star Trek - a small contingent of minority characters in supporting roles - considered radical and progressive just five years before, was, if not quite commonplace, then at least far from unusual. Even the long-running western, "Bonanza", was well-known for its sympathetic portrayals of minority characters.

But, as in society in general, for all the advances that had been made, the struggle to win hearts and minds was ongoing, and there continued to be setbacks. Critics of racial integration, and indeed, any non-stereotypical depiction of African-American characters, made their opinions known about their increased presence on television. Though ABC and CBS also had a minority presence, they were most visible on NBC, and thus they were the primary target of detractors; they even targeted Star Trek, which was now in syndication, and no longer had anything to do with the network (though many affiliated stations would air the show on weekdays at 7:00 PM). The famous claim that NBC was the network of "Negroes, Blacks, and Coloreds" [4] (which, sadly, was actually the bowdlerized term) also dates from this era; it was popularly attributed to then-Governor of Alabama, staunch segregationist, and past (and future) Presidential candidate, George Wallace, though this is almost certainly apocryphal. [5] Indeed, the harshest media critics of minority representation tended to focus more strongly on television, having effectively "ceded" any aspirations for reversals in the movies. For in addition to Porno Chic, another famous trend of the early 1970s, Blaxploitation, was riding high. For the first time, movies made by black filmmakers and intended for black audiences were being produced on a large scale, though the nature of much of its content was morally ambiguous - indeed, the genre was stereotyped as featuring drug dealers, pimps, and gangsters, all going about their business and fighting against "The Man" (invariably white, and often corrupt law enforcement). The truth, as is always the case, was more nuanced and complex. But without question, the genre stuck a chord with audiences. One of the most famous Blaxploitation films, Shaft, won Isaac Hayes an Academy Award for Best Original Song, making him the first person of colour to win an Oscar for any discipline other than acting; he would later dedicate his win to "the black community". On the whole, if minority representation in the media could be taken as a microcosm of their overall place in society, there was cause for optimism, but there was still plenty of progress yet to be made.

As always, in the face of dramatic societal changes, life continued to go on in the television industry, especially at those two neighbouring studios in Culver City. Herbert F. Solow's promotion to SEVP and COO of Desilu necessitated a shake-up among the line positions at the company, most obviously in creating a need to hire his replacement as Vice-President in Charge of Production. Solow suggested his close friend, and a proven administrative talent, Robert H. Justman, for the position; Lucille Ball accepted this proposition, and he was immediately hired. From then on, and despite all the care and attention that he had devoted to Star Trek, Justman would now have to juggle the interests of the three other shows currently running, as well as the various pilots that the studio was developing, in order to have another show on the air for the 1972-73 season. Gene Roddenberry was one of the several producers to come to Desilu with a pitch, hoping to renew his association with the "House that Paladin Built", and was optimistic about his odds, given his friendships with Solow, Justman, and Ball. They all liked his pitch, about a man from the present day, flung forward in time by an unfortunate accident [6], but they also remembered the difficulties in getting Star Trek off the ground first-hand. It was Justman who eventually suggested selling the idea as a pilot movie, allowing them to recoup as much of their potential losses as possible. This meant that any series would not begin airing until at least the 1973-74 season, which obviously displeased Roddenberry a great deal; in exchange for this setback, Solow offered him the chance to develop another pilot, with the potential of ultimately having two shows on the air at the same time. Gene, who despite the lofty ideals of his most famous creation, was himself rather avaricious, jumped at the opportunity.

What was now the undisputed senior show in the Desilu stable, "Mission: Impossible", continued into its sixth season apace. The previous two-year contract with Martin Landau and Barbara Bain had expired, but a new one was drawn up with surprising ease, given the resources that had been freed up by the conclusion of Star Trek. Nonetheless, Landau and Bain continued to drive a hard bargain, and it was decided by all parties - led by the notoriously frugal Justman, in his first major decision as VP of Production - that this two-year extension would be the last. This essentially meant that the show would be finished after that, for who would want to go on without Rollin Hand and Cinnamon? [7] But despite securing their continued presence, the show did not go on without one major casualty: Peter Lupus, having grown weary of his role, was unable to come to terms in re-negotiations; his departure marked the end of the "classic" lineup, which lasted for four seasons. He was replaced by Sam Elliott [8] for the remainder of the show's run.

But one of the studio's primary challenges came from the question of how to handle the incoming footage from Doctor Who, which Desilu - under the terms of their syndication deal with the BBC - were now obliged to compile into the final product. Here it was Solow who devised the winning solution: dedicated post-production facilities, staffed by the now-unemployed effects artists and editors who had worked on Star Trek. Such a facility could function as a separate division of the studio, and it would be able to generate revenue; for in addition to keeping the post-production work for Desilu in-house, they could also accept work from outside sources. Ball, for her part, wasn't particularly enthusiastic about the idea, but she trusted the judgment of her key lieutenant, and agreed to establish what would become known as Desilu Post-Production. All of the post-production workers for the various shows being produced were to work out of this division, and be "assigned" to a given series as needed; in practice, this new bureaucratic arrangement had very little effect on the average editor's day-to-day life. Solow also hired a few additional technicians to accommodate the work coming in from outside the studio; one of the handful of editors brought on board was a young woman named Marcia Lucas. [9]

Meanwhile, at Paramount, the company had more good news to report when "Room 222", once on the brink of cancellation, had risen into the Top 30 for the 1971-72 season, alongside their established hit, "Mary Tyler Moore". Their two other shows, "Barefoot in the Park" and "The Odd Couple", continued to do well enough to justify their continued renewal; so Grant Tinker, whose creative juices were always flowing, decided to develop a fifth series. He commissioned a pilot from two "Mary Tyler Moore" writers, Lorenzo Music and David Davis, in the hopes of creating another star vehicle for another popular entertainer of the 1960s: button-down comedian Bob Newhart.

At the Emmy Awards for that season, held in May, 1972, Elizabeth R, produced by the BBC and aired by PBS in the United States, won the Award for Outstanding Dramatic Series. It was the first time in six years that Desilu did not win the award; the star of the series, Oscar-winning actress Glenda Jackson, also received an Emmy for her performance as the Virgin Queen. On the Comedy side of the ledger, Those Were the Days repeated for Series, as did Jean Stapleton for Lead Actress; this time, Carroll O'Connor also won, for Lead Actor, as did their onscreen daughter, Penny Marshall, for Supporting Actress. (The fourth cast member, Richard Dreyfuss, was not eligible in any category; the relevant category, Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Comedy Series, was first awarded at the following year's ceremony.) "The Flip Wilson Show" repeated for Outstanding Variety Series, and Star Trek was presented with a Special Emmy Award in recognition of its creative achievements throughout its run, which was accepted by the show's producers. [10] This combination of fresh faces and continuity at the awards ceremony was clearly reflective of the television landscape as a whole...

---

[1] IOTL, NBC had eight Top 30 hits this season, including the mid-season pick-up "Sanford and Son", and three in the Top 10 (again including "Sanford"); ABC had eight in the Top 30, and two in the Top 10; CBS had fourteen in the Top 30, and five in the Top 10.

[2] "The Bill Cosby Show" ran from 1969 to 1971 IOTL. More favourable scheduling results in the show remaining in the Top 30 for its second season, which allows it to come back for a third. This provides the opportunity for the "Battle of the Superstars" sketch, which does not exist IOTL. Among other things, this also means that Cosby will not join the cast of "The Electric Company".

[3] "Julia" also benefits from better scheduling, and therefore better ratings, narrowly making the Top 30; it also returns for a fourth season, after which it will reach the magic 100 episodes and become eligible for syndication.

[4] This term was never used IOTL; here, the continued run of "Bill Cosby" and "Julia" on NBC in addition to "Flip Wilson", and now "Sanford" as well, along with the enduring legacy of Star Trek (and "Bonanza"), is enough to give the network an (exaggerated) reputation as "the black network", similar to OTL FOX in the early 1990s, and then UPN at the turn of the millennium.

[5] No, Wallace did not coin the term ITTL; the accusation that he did was thrust upon him in the 1972 election campaign, and given his apathy and, when pressed, half-hearted denials regarding the subject, it became popular to assume that he had, in fact, said it.

[6] The pitch being described is the same basic premise as Genesis II, which only got as far as the pilot movie phase IOTL. It was later completely re-worked, developed and (originally) produced by Robert Hewitt Wolfe, and aired as "Gene Roddenberry's Andromeda". (And yes, the premise is also very similar to a certain mostly-comedic cartoon series.)

[7] The correct answer to that question is: the people of OTL, who continued to watch "Mission: Impossible" for four seasons after the departure of Landau and Bain - longer, in fact, than their three season tenure. Among their replacements was Leonard Nimoy, who had just been fired from Star Trek; famously, all he had to do to get to his new job was just walk across the lot.

[8] IOTL, Elliott joined the cast during season six, but audiences didn't take to his character; Lupus was eventually brought back, with the promise of a meatier role. ITTL, with the continuing presence of Landau and Bain, he won't be missed nearly as much.

[9] Yes, that Marcia Lucas.

[10] Most of the Emmy wins here are as IOTL, with two exceptions: Marshall, a better actress than Struthers, wins her Emmy outright instead of Struthers sharing it in a tie with Valerie Harper; and "Flip Wilson" wins for Variety Series over "The Carol Burnett Show". (And, obviously, Star Trek did not win a Special Emmy IOTL.)

---

So here we are with another look at the sociopolitical situation of TTL in the early 1970s! Part of my motivation in making this update was to remind everyone that this is not a utopia - race relations are generally better, and that's duly reflected on television (in the movies less so, given the existence of Blaxploitation as a "release valve"), but there's going to be resistance, and people weren't as eager to be politically correct in the early 1970s. Humphrey is going about desegregation ITTL in much the same way that Nixon did IOTL, only he's a lot louder about it; and people tend to fight back a lot harder when they're up against the wall.

I hope that you all find some of the plot threads I'm developing here to be intriguing. It's all going to build rather slowly and deliberately compared to the (relatively) fast pace of the early years, but I still don't see my update schedule falling below approximately one update per week. So, until next time, thank you all for reading, and I will greatly appreciate your comments on this and all other posts!

"This is the big one!"

- Fred Sanford, "Sanford and Son"

The 1971-72 season was the first of the "Modern TV" era, though several later analysts would, with characteristic pretentiousness, describe this period in television as subsumed within the greater "New Hollywood" movement; but this would be an overly simplistic generalization. Certainly, the continued presence of the Standards & Practices departments at all three commercial networks, coupled with strong regulations by the FCC, prevented the spread of explicit sexual content and violence from the big screen to the small one. For example, "porno chic", a movement which was on the rise in American cinema at the time, would have no equivalent in television. Even the most controversial show on the air, Those Were the Days, didn't dare show their characters moving beyond first base. Furthermore, producers still lacked the creative freedom enjoyed by filmmakers, and were tethered to strict budgets and tough scheduling deadlines. Some of the studios were more indulgent than others, but there was still a tremendous difference between how they handled weekly series and how they handled major motion pictures. It was no coincidence that the most indulgent studio wasn't even in the movie business.

The three commercial networks were forced to adapt to the new twenty-one hour primetime schedules, and some of them were coping better than others. CBS, despite having cancelled nearly two-fifths of their 1970-71 lineup, seemed to be taking it the best, though any potentially dissenting voices were tightly muzzled by Fred Silverman, who took to describing his leaner, meaner network as "a new CBS for a new era of television", helping to cement the idea of a dividing line between "Classic TV" and "Modern TV" within the industry.

NBC executives found themselves torn. They had 11 Top 30 hits for the season, more than any other network; [1] but their programming choices were, to say the least, erratic. All three of their major Westerns (which, by the early 1970s, were considered a "dinosaur" genre) remained on the air, but at the same time, they carried the most racially diverse lineup on television. Their top-rated show (ranked #2 overall in both 1970-71 and 1971-72) was a variety program starring a black comedian, Flip Wilson; he was described by Time Magazine, in their January 31, 1972 issue, as "TV's First Black Superstar". This designation was playfully challenged by Bill Cosby, a frequent guest on Wilson's show, who also starred on an eponymous series (a sitcom) [2] on NBC, resulting in the famous "Battle of the Superstars" sketch. Many observers noted that, although there had been no black performers in recurring, non-stereotypical roles on television just seven years before, now there were two big TV stars, both of whom were very popular with white audiences. And this disregarded the other shows on NBC with black leads: "Julia", starring Diahann Carroll [3], and, partway through the season, a new series with a largely black cast: "Sanford and Son". It starred another black comedian, Redd Foxx, and also gained traction with white audiences, becoming the highest-rated new show of the year. Indeed, even a program with the racial composition of Star Trek - a small contingent of minority characters in supporting roles - considered radical and progressive just five years before, was, if not quite commonplace, then at least far from unusual. Even the long-running western, "Bonanza", was well-known for its sympathetic portrayals of minority characters.

But, as in society in general, for all the advances that had been made, the struggle to win hearts and minds was ongoing, and there continued to be setbacks. Critics of racial integration, and indeed, any non-stereotypical depiction of African-American characters, made their opinions known about their increased presence on television. Though ABC and CBS also had a minority presence, they were most visible on NBC, and thus they were the primary target of detractors; they even targeted Star Trek, which was now in syndication, and no longer had anything to do with the network (though many affiliated stations would air the show on weekdays at 7:00 PM). The famous claim that NBC was the network of "Negroes, Blacks, and Coloreds" [4] (which, sadly, was actually the bowdlerized term) also dates from this era; it was popularly attributed to then-Governor of Alabama, staunch segregationist, and past (and future) Presidential candidate, George Wallace, though this is almost certainly apocryphal. [5] Indeed, the harshest media critics of minority representation tended to focus more strongly on television, having effectively "ceded" any aspirations for reversals in the movies. For in addition to Porno Chic, another famous trend of the early 1970s, Blaxploitation, was riding high. For the first time, movies made by black filmmakers and intended for black audiences were being produced on a large scale, though the nature of much of its content was morally ambiguous - indeed, the genre was stereotyped as featuring drug dealers, pimps, and gangsters, all going about their business and fighting against "The Man" (invariably white, and often corrupt law enforcement). The truth, as is always the case, was more nuanced and complex. But without question, the genre stuck a chord with audiences. One of the most famous Blaxploitation films, Shaft, won Isaac Hayes an Academy Award for Best Original Song, making him the first person of colour to win an Oscar for any discipline other than acting; he would later dedicate his win to "the black community". On the whole, if minority representation in the media could be taken as a microcosm of their overall place in society, there was cause for optimism, but there was still plenty of progress yet to be made.

As always, in the face of dramatic societal changes, life continued to go on in the television industry, especially at those two neighbouring studios in Culver City. Herbert F. Solow's promotion to SEVP and COO of Desilu necessitated a shake-up among the line positions at the company, most obviously in creating a need to hire his replacement as Vice-President in Charge of Production. Solow suggested his close friend, and a proven administrative talent, Robert H. Justman, for the position; Lucille Ball accepted this proposition, and he was immediately hired. From then on, and despite all the care and attention that he had devoted to Star Trek, Justman would now have to juggle the interests of the three other shows currently running, as well as the various pilots that the studio was developing, in order to have another show on the air for the 1972-73 season. Gene Roddenberry was one of the several producers to come to Desilu with a pitch, hoping to renew his association with the "House that Paladin Built", and was optimistic about his odds, given his friendships with Solow, Justman, and Ball. They all liked his pitch, about a man from the present day, flung forward in time by an unfortunate accident [6], but they also remembered the difficulties in getting Star Trek off the ground first-hand. It was Justman who eventually suggested selling the idea as a pilot movie, allowing them to recoup as much of their potential losses as possible. This meant that any series would not begin airing until at least the 1973-74 season, which obviously displeased Roddenberry a great deal; in exchange for this setback, Solow offered him the chance to develop another pilot, with the potential of ultimately having two shows on the air at the same time. Gene, who despite the lofty ideals of his most famous creation, was himself rather avaricious, jumped at the opportunity.

What was now the undisputed senior show in the Desilu stable, "Mission: Impossible", continued into its sixth season apace. The previous two-year contract with Martin Landau and Barbara Bain had expired, but a new one was drawn up with surprising ease, given the resources that had been freed up by the conclusion of Star Trek. Nonetheless, Landau and Bain continued to drive a hard bargain, and it was decided by all parties - led by the notoriously frugal Justman, in his first major decision as VP of Production - that this two-year extension would be the last. This essentially meant that the show would be finished after that, for who would want to go on without Rollin Hand and Cinnamon? [7] But despite securing their continued presence, the show did not go on without one major casualty: Peter Lupus, having grown weary of his role, was unable to come to terms in re-negotiations; his departure marked the end of the "classic" lineup, which lasted for four seasons. He was replaced by Sam Elliott [8] for the remainder of the show's run.

But one of the studio's primary challenges came from the question of how to handle the incoming footage from Doctor Who, which Desilu - under the terms of their syndication deal with the BBC - were now obliged to compile into the final product. Here it was Solow who devised the winning solution: dedicated post-production facilities, staffed by the now-unemployed effects artists and editors who had worked on Star Trek. Such a facility could function as a separate division of the studio, and it would be able to generate revenue; for in addition to keeping the post-production work for Desilu in-house, they could also accept work from outside sources. Ball, for her part, wasn't particularly enthusiastic about the idea, but she trusted the judgment of her key lieutenant, and agreed to establish what would become known as Desilu Post-Production. All of the post-production workers for the various shows being produced were to work out of this division, and be "assigned" to a given series as needed; in practice, this new bureaucratic arrangement had very little effect on the average editor's day-to-day life. Solow also hired a few additional technicians to accommodate the work coming in from outside the studio; one of the handful of editors brought on board was a young woman named Marcia Lucas. [9]

Meanwhile, at Paramount, the company had more good news to report when "Room 222", once on the brink of cancellation, had risen into the Top 30 for the 1971-72 season, alongside their established hit, "Mary Tyler Moore". Their two other shows, "Barefoot in the Park" and "The Odd Couple", continued to do well enough to justify their continued renewal; so Grant Tinker, whose creative juices were always flowing, decided to develop a fifth series. He commissioned a pilot from two "Mary Tyler Moore" writers, Lorenzo Music and David Davis, in the hopes of creating another star vehicle for another popular entertainer of the 1960s: button-down comedian Bob Newhart.

At the Emmy Awards for that season, held in May, 1972, Elizabeth R, produced by the BBC and aired by PBS in the United States, won the Award for Outstanding Dramatic Series. It was the first time in six years that Desilu did not win the award; the star of the series, Oscar-winning actress Glenda Jackson, also received an Emmy for her performance as the Virgin Queen. On the Comedy side of the ledger, Those Were the Days repeated for Series, as did Jean Stapleton for Lead Actress; this time, Carroll O'Connor also won, for Lead Actor, as did their onscreen daughter, Penny Marshall, for Supporting Actress. (The fourth cast member, Richard Dreyfuss, was not eligible in any category; the relevant category, Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Comedy Series, was first awarded at the following year's ceremony.) "The Flip Wilson Show" repeated for Outstanding Variety Series, and Star Trek was presented with a Special Emmy Award in recognition of its creative achievements throughout its run, which was accepted by the show's producers. [10] This combination of fresh faces and continuity at the awards ceremony was clearly reflective of the television landscape as a whole...

---

[1] IOTL, NBC had eight Top 30 hits this season, including the mid-season pick-up "Sanford and Son", and three in the Top 10 (again including "Sanford"); ABC had eight in the Top 30, and two in the Top 10; CBS had fourteen in the Top 30, and five in the Top 10.

[2] "The Bill Cosby Show" ran from 1969 to 1971 IOTL. More favourable scheduling results in the show remaining in the Top 30 for its second season, which allows it to come back for a third. This provides the opportunity for the "Battle of the Superstars" sketch, which does not exist IOTL. Among other things, this also means that Cosby will not join the cast of "The Electric Company".

[3] "Julia" also benefits from better scheduling, and therefore better ratings, narrowly making the Top 30; it also returns for a fourth season, after which it will reach the magic 100 episodes and become eligible for syndication.

[4] This term was never used IOTL; here, the continued run of "Bill Cosby" and "Julia" on NBC in addition to "Flip Wilson", and now "Sanford" as well, along with the enduring legacy of Star Trek (and "Bonanza"), is enough to give the network an (exaggerated) reputation as "the black network", similar to OTL FOX in the early 1990s, and then UPN at the turn of the millennium.

[5] No, Wallace did not coin the term ITTL; the accusation that he did was thrust upon him in the 1972 election campaign, and given his apathy and, when pressed, half-hearted denials regarding the subject, it became popular to assume that he had, in fact, said it.

[6] The pitch being described is the same basic premise as Genesis II, which only got as far as the pilot movie phase IOTL. It was later completely re-worked, developed and (originally) produced by Robert Hewitt Wolfe, and aired as "Gene Roddenberry's Andromeda". (And yes, the premise is also very similar to a certain mostly-comedic cartoon series.)

[7] The correct answer to that question is: the people of OTL, who continued to watch "Mission: Impossible" for four seasons after the departure of Landau and Bain - longer, in fact, than their three season tenure. Among their replacements was Leonard Nimoy, who had just been fired from Star Trek; famously, all he had to do to get to his new job was just walk across the lot.

[8] IOTL, Elliott joined the cast during season six, but audiences didn't take to his character; Lupus was eventually brought back, with the promise of a meatier role. ITTL, with the continuing presence of Landau and Bain, he won't be missed nearly as much.

[9] Yes, that Marcia Lucas.

[10] Most of the Emmy wins here are as IOTL, with two exceptions: Marshall, a better actress than Struthers, wins her Emmy outright instead of Struthers sharing it in a tie with Valerie Harper; and "Flip Wilson" wins for Variety Series over "The Carol Burnett Show". (And, obviously, Star Trek did not win a Special Emmy IOTL.)

---

So here we are with another look at the sociopolitical situation of TTL in the early 1970s! Part of my motivation in making this update was to remind everyone that this is not a utopia - race relations are generally better, and that's duly reflected on television (in the movies less so, given the existence of Blaxploitation as a "release valve"), but there's going to be resistance, and people weren't as eager to be politically correct in the early 1970s. Humphrey is going about desegregation ITTL in much the same way that Nixon did IOTL, only he's a lot louder about it; and people tend to fight back a lot harder when they're up against the wall.

I hope that you all find some of the plot threads I'm developing here to be intriguing. It's all going to build rather slowly and deliberately compared to the (relatively) fast pace of the early years, but I still don't see my update schedule falling below approximately one update per week. So, until next time, thank you all for reading, and I will greatly appreciate your comments on this and all other posts!

Last edited: