Where's the assumption? I stated a fact. If Reagan is assassinated, and it seems likely that someone will at least try, then that almost certainly results in four different Vice Presidents of the United States in a span of approximately two years.You are making assumptions. Anything can happen.

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Texas Two-Step: Nixon nominates Connally as VP in 1973

- Thread starter wolverinethad

- Start date

Question—what is the OTL basis for the French Intel referenced in your post? Otherwise, great thread

I apparently misunderstood the tone of the comment and apologize.Where's the assumption? I stated a fact. If Reagan is assassinated, and it seems likely that someone will at least try, then that almost certainly results in four different Vice Presidents of the United States in a span of approximately two years.

Adolf Tolkachev, the "Billion Dollar Spy." He actively pursued contacts with Americans in 1977-78 because he wanted out of the USSR, and had access to a ton of useful intel, since he worked at the MiG design bureau. In this timeline, he makes his move sooner and approaches the French instead, as the thought of the KGB chairman running the nation scares him deeply. They gladly take the bait, and pass along the fighter designs to NATO allies. Valery Giscard D'Estaing is not de Gaulle, and in the wake of Korea sees value in cooperation.Question—what is the OTL basis for the French Intel referenced in your post? Otherwise, great thread

A note to readers

Hello.

Your friendly author made a couple of sleep-deprived booboos in the last installment, which have now been corrected.

I wrote Admiral Radford twice when it was meant to be Admiral Burke. I regret the error.

Furthermore, in reading back on earlier chapters to refresh my memory on something I wanted to tie together, I realize that I made a storyline course correction, but forgot to add the explainer sentences for it. As careful readers may remember, the original Cabinet plan had the sudden elevation of Bobby Ray Inman to CIA Director from Naval Intelligence. However, I decided to create an additional shuffle, and forgot to explain it, so two chapters later, it's suddenly Paul Nitze as director.

As I hate plot holes, I'm going to explain this. The announcement of Inman was a dead duck on Capitol Hill, and Connally quickly pivoted, announcing Nitze as director instead of U.N. Ambassador. After some prevaricating, Jack Matlock was nominated and confirmed near-unanimously for U.N. Ambassador, and Inman stayed at Naval Intelligence as director.

Your friendly author made a couple of sleep-deprived booboos in the last installment, which have now been corrected.

I wrote Admiral Radford twice when it was meant to be Admiral Burke. I regret the error.

Furthermore, in reading back on earlier chapters to refresh my memory on something I wanted to tie together, I realize that I made a storyline course correction, but forgot to add the explainer sentences for it. As careful readers may remember, the original Cabinet plan had the sudden elevation of Bobby Ray Inman to CIA Director from Naval Intelligence. However, I decided to create an additional shuffle, and forgot to explain it, so two chapters later, it's suddenly Paul Nitze as director.

As I hate plot holes, I'm going to explain this. The announcement of Inman was a dead duck on Capitol Hill, and Connally quickly pivoted, announcing Nitze as director instead of U.N. Ambassador. After some prevaricating, Jack Matlock was nominated and confirmed near-unanimously for U.N. Ambassador, and Inman stayed at Naval Intelligence as director.

January 19, 1975

The AH-56 Cheyenne attack helicopters were ready for first use in support of the South Vietnamese. Twenty trained CIA pilots, with second-seaters and ground crew on loan from the Army, along with the helicopters and armaments, were flown in two C-5 Galaxy transport planes to Tan Son Nhut Air Base outside Saigon and immediately wheeled into hangars that had been cleared for them. Their presence was to be a surprise. Roughly ten days earlier, Phước Long, a provincial capital considered vital for the defense of Saigon, had fallen to North Vietnamese forces. The intel that was received through intercepts showed that the NVA were convinced that America no longer cared to help Saigon and they were requesting additional supplies from the Soviets and Chinese to reinforce their front line and to mass an invasion into the Central Highlands. As Paul Nitze acidly remarked at Langley when reading the transcript, “They are about to be disabused of their notion that we don’t care.”

Five platoons of four Cheyennes each were fueled up, loaded up, and lifted off at dawn, heading northeast towards the NVA encampment. There was a mix of armor, artillery, some SAMs (much had been expended against the RVNAF A-7s which provided support during the weeks of siege), and a lot of infantry. As the Cheyennes approached, they could see on their long-range scopes that the NVA were being a bit lazy, not having taken precautions against an air assault such as theirs. They probably think it’s all over now, one of the pilots thought. You little bastards are about to get a big surprise. The initial assault was going to be three platoons, with two hanging outside the area, ready to capitalize on the NVA’s reaction to what was coming. The main weapons were four BGM-TOW 71 missiles on the outer hardpoints, with 2.75 inch cluster rockets on the two inner hardpoints. In the nose of the Cheyenne was an M134 minigun loaded with NATO 7.62mm bullets, and a 30mm cannon attached to the belly of the chopper. Reaching the combat zone, the TOWs were fired off first, wiping out a dozen T-54 tanks and waking up the sleeping NVA soldiers as those who were near the end of their watch were jolted from semi-sleep to terrified alertness. The miniguns were used to spray the soldiers as they ran, ripping them apart with a literal hailstorm of bullets. The rockets were fired at the light-skinned PT-76 “tanks” that were really nothing more than a glorified Soviet version of a basic M113 and tore right through the thin aluminum armor.

There was a determined effort by the NVA’s 7th Infantry to get the artillery to a place of safety, and SA-7s were hoisted and launched, however, the low altitude and constant movement of the Cheyennes meant that they couldn’t gain infrared lock before rocketing past harmlessly into the skies. This was an issue that the SA-7b had corrected, but the NVA were armed with surplus 7a variants, which engaged low altitudes relatively well, but only from behind, and those targets were the slower moving Hueys carrying infantry. A fast-moving attack helicopter did not meet those guidelines, and the NVA was paying a price now. After expending their missiles/rockets, and most of the 30mm cannon ammo, the first attack began peeling off, and the artillery group stopped moving for a moment, their eyes glued to the skies as the platoons of attack helicopters receded into the distance. This was a fatal, yet entirely understandable error. As the soldiers believed the assault was over, they were taking a breather, the adrenaline receding...and then the second wave of two platoons rose up over the horizon at their rear, and volleyed their TOW missiles into the artillery regiment, destroying most of the guns and virtually all of the ammunition for them. An ammunition dump was spotted by one of the pilots, and that Cheyenne banked hard left and loosed a couple of 30mm cannon rounds into it, sending a tremendous geyser of flame and smoke into the sky. Ammo dumps were rare for the NVA and Vietcong, as they believed in traveling light, but this assault on Phước Long had been with the design of creating a strategic foothold to launch the final assault on Saigon, and so they’d brought more supplies forward than the norm to supply that assault. It was all done with the belief that the Americans had left this war and didn’t care to help Saigon. Complacent, sure of rapid victory, the three divisions of the NVA lead forces had been left disorganized and without most of their heavy weaponry. The raid was completed with not a single helicopter shot down by the NVA forces, too stunned by the appearance of these new, larger helicopters with the ability to destroy T-54s from the air. The remnants were soon driven back into Cambodia by regrouped RVN forces that had just lost the city ten days ago. The AH-56s had all flown with the decals of the RVNAF, with nary a sign that Americans were piloting them, and when word reached Hanoi, there was great confusion as to what had happened. This was decidedly not the case in Washington, where the President was ecstatic with the results. The generals were delighted because it proved the worth of attack helicopters in this role. The CIA was delighted because they’d successfully pulled off a covert op despite the increased scrutiny they were under.

Enquiries were made by the North Vietnamese with their Soviet sponsors, who were equally as surprised. They knew from their sources that only a single AH-64 Apache helicopter had been built, and while some of the more finely tuned analysts had raised the question of the Cheyennes, the consensus from their KGB/GRU superiors was that it wasn’t possible, because the Americans hadn’t built that many, and some had already gone to museums. A coded signal was sent to a deep cover KGB officer in Florida, who drove up to Tallahassee, meeting a lovely young woman in her junior year who was active in the remnants of the peace movement on the campus of Florida State. He asked her to please have her boyfriend, a low-level draftee at Fort Rucker, check to see if they still had the AH-56 on display outside of the aviation museum there. The cover story the KGB man provided was that they’d [the peace movement] heard a rumor that the South Vietnamese bought them to use in the war. The private first class went over to the museum after the end of his duty schedule for the day, and saw an AH-56 sitting on the lawn, just as it had been. Now, being a young man only twenty years old, he didn’t look too closely, and so therefore did not observe that what sat on the lawn was an aluminum fabrication, with iron ballast inside the shell to keep it weighed down. The CIA had thought their deception through, and recognized that the sudden disappearance of museum pieces around the country might be noticed, so basic models were fabricated that would fool any casual onlooker, because who took time to inspect a museum piece that was on the lawn and roped off? When the KGB received confirmation that the AH-56 was still in its museum location, they eagerly informed their GRU comrades, and the North Vietnamese, that whatever it was, it wasn’t American. This bravado was misplaced, but hardly surprising. The opinion of the world was that America, in general, was in decline. It was the same for France, and Great Britain, the old Allied powers were all in economic malaise, trying to fight off inflation, beset by labor problems, and unable to wield power as they once had.

A President less self-confident than John Connally likely would’ve limply asked Congress for aid, and not tried any sort of covert action after the impeachment and conviction of their predecessor, but John Connally was a man of action, and he’d decided months ago that he would not take North Vietnam’s complete abrogation of the treaty they signed lying down. Congress would probably start squealing whenever the world figured out that America had supplied wonder weapons to the RVNAF, press the administration on the issue, call Nitze up to the Hill to testify. Nitze would tell them that it was better they be used helping an ally than gathering dust in a museum. Marvin Kalb would issue a statement from the White House that it was the duty of the nation to enforce treaties it was a signatory to. What would Congress do? Throw a tantrum and start a bunch of investigations about twenty helicopters? Connally doubted they would want to drag America through that again, and unlike Dick, he didn’t waver back and forth, needing handholding to make his decisions. He’d run through his options, decide on the best one, and take action. If the South could hold out and force a stalemate, Connally had already discussed with Clements the idea of offering a discounted production run of more to assist in their defense. It’d keep the Lockheed factories running longer, and that was just good economic sense. As it was, the last ten that had been paid for by the reprogrammed Pentagon funds were in production now, and would be over there soon enough. The A-10 was about to start a production run for advanced testing prior to acceptance. If the Republic of Vietnam made it to 1976, he’d sell some of the A-10s to Thieu, have the pilots from the RVNAF go to Thailand, or to Clark AFB in the Philippines, learn how to fly them, and then take delivery and fly back to Saigon. Americans didn’t have to fight themselves to hold the South, not with new weapons and aircraft that the NVA were ill-equipped to fight. These were precision weapons, able to be flown at the treetops or lower, armed with far more firepower than the Huey Cobras with their miniguns and singular rocket pod.

Twenty helicopters had completely stalled three divisions of infantry and armor. The shape of war was changing again.

*****

In Long Beach, an odd ship was leaving port for the second time. It wasn’t quite a container ship, not quite an exploration vessel. The Hughes Glomar Explorer was, publicly anyway, designed for the mining of manganese nodules on the floor of the Pacific Ocean. It was an odd quest, but Howard Hughes, the titular builder of the ship, had long been known for his odd interests, and so nobody was surprised by the announcement, as it was perfectly in character for the man.

Mining was not what the Glomar was built to do. It was purpose-built for one task: to recover the remains of a Soviet Golf-class nuclear missile submarine known as K-129. In 1968, the Golf had suffered a catastrophic failure of unknown origin and sank to the bottom of the Pacific while sitting outside one of the routes into Pearl Harbor used by the United States Navy. The USS Halibut, an early-generation nuclear attack sub fitted with special equipment, was able to get a camera down to the ocean floor where it laid, and Richard Nixon had approved the Glomar’s mission and building in 1970. Right after the conviction of Nixon by the Senate, the massive ship had left Long Beach for its first attempt to raise the sub. However, during a test run with the large grabber hand its crew had named Clementine, several of the large steel fingers had broken badly. As the ship was not too far along in its journey, the decision was made to return to port for repairs. While the engineers examined it, they determined that the fingers, while very strong, did not retain flexibility under sea pressure, and that was why they broke off. It took another six months to manufacture fingers with a new composite steel, which was tested repeatedly and determined to be sufficient for the task. This trip, unlike the first one, did not draw the same sort of curiosity as the first launch, and was done at night to escape prying eyes. This included the Soviet “fishing trawlers” that were used to spy on U.S. military operations worldwide. The Glomar took a leisurely path over the next two weeks to Hawaii, moving at their limited maximum speed of ten knots, arriving on February 2nd. What transpired during the next five days would become the subject of heated debate when the story became public months later.

*****

Three days after the Glomar Explorer arrived at the wreckage of K-129, British Prime Minister Harold Wilson rose to give his opening statement during Prime Minister’s Questions. Mere minutes before, a letter had been delivered to Her Majesty informing her of the bombshell he was about to drop in front of Parliament: the announcement that he would resign as soon as a successor could be chosen. He stated that he was experiencing health issues that rendered him unsuitable to continue as the leader of Her Majesty’s Government. Wilson stated that he would not back any candidate, as he wanted the vote to not be influenced by how he felt, but how the parliamentary party felt. He stepped down from the rostrum, and Edward Heath, his longtime foe, a man who simply could not stand Wilson’s smoothness with voters, stood up to speak. Heath, for all of his quirks, was at heart an honorable man. One civil servant at Number Ten said of him, “I like Mr. Wilson and I always got on smashingly with him. He knew how to talk to people, but I never could quite trust him. Mr. Heath was not good with small talk, but I absolutely trusted him. I’ve never met a man with the sort of integrity he has.” So, upon his rising, he spoke of his sadness that Wilson was suffering from health issues and hoped that he could, through treatment, continue to lead a long and enjoyable life. Heath added, “Though he bested me more times than I care to admit, he has served his country honorably for many years, and his support as we approach the European Community referendum has been most appreciated. That project has been closest to my heart for two decades, and the fact that a political adversary such as he could throw his support behind an issue that his opponent has championed for so long speaks volumes to his character. I thank you, Prime Minister, and I wish you a well-deserved retirement.”

The rarest of moments from the past decade occurred then, as the Labour benches rose at one to applaud the statement, with many of the Tories doing so as well. Not everyone cared to rise. Certainly Margaret Thatcher did not. The dour look on her face stood out amongst the more jovial, or sad, visages of the others around her. Enoch Powell looked pleasant enough as he provided a mere golf clap for Wilson. He was in quite a unique position, because he hated both Wilson and Heath; Wilson for his politics, and Heath for exiling him to the backbenches. Both he and Thatcher were potential rivals to challenge Heath for leadership of the party, for nobody had survived in leadership of the Conservative Party with the electoral record of Heath. Even Clement Attlee, though many forgot, had won twice as leader to his three losses for Labour. Had Heath done just a little bit better a year before, there wouldn’t be a Lab-Lib government, for the Tories drew more votes, but not enough seats for a majority. In a sense, he had won, but not well enough.

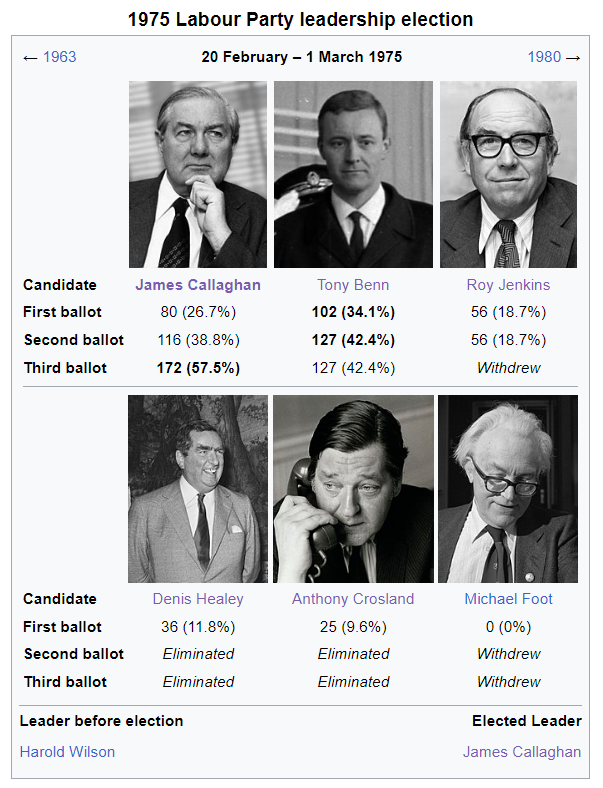

On the Labour side, as Wilson believed a year ago, half of his Cabinet was already polling the members to get a sense of their fortunes. James Callaghan, the Foreign Secretary, Denis Healey, the suffering Chancellor of the Exchequer, Tony Benn, the Energy Secretary, Michael Foot, the leader of the House, Tony Crosland, the very able Environment Secretary, and Home Secretary Roy (“Woy”) Jenkins were all standing. Benn represented the true socialist left of the party, Jenkins the sensible center of it, with Foot closest to Benn’s position and Crosland closest to Jenkins, while Callaghan and Healey sat between those two sides. Labour had a lot of positive accomplishments to look back on for the past thirty years: decimalization, the creation of the National Health Service, a robust economy during the latter half of the 1960s, responsible stewardship of the pound, and numerous public housing works to reduce homelessness. By the same token, the unions in Britain, stricken by inflation, had become more militant than ever before, and steadfastly refused to negotiate wages in any accordance with the current economic situation. Healey flat-out despaired of keeping the lid on the boiling pot. He was in near-daily contact with Canadian Finance Minister John Turner (a lad from Surrey, of all places!), Italian Finance Minister Bruno Visentini, French Prime Minister/Finance Minister Raymond Barre, West German Finance Minister Hans Apel, and United States Treasury Secretary Nelson Rockefeller. They were set to meet in May at Rambouillet in France, prior to the first G6 meeting of their nation’s leaders. Connally and Rockefeller had been pushing the need to keep inflation down in a responsible way so as to not trigger a recession. France had been doing the best, as Barre’s government had been investing in infrastructure, which helped workers build their bank accounts, and they’d also raised pension benefits, which helped the old and poor participate in the economy to a greater degree. The West Germans continued to chug along with innovation after innovation in the realms of automotive engineering and technology, producing excellent vehicles on par with the Japanese for fuel economy. Canada and America were joined at the hip, and Britain was muddling along, stuck in a malaise not entirely of their own making. The pullback by the French from NATO, and the lack of contribution from smaller nations towards the common defence had put more of the onus on Britain, and between the development of nuclear weapons, maintaining their strong navy, and the British Army On the Rhine, too much of their money went to defence and not enough towards investment.

The British were further hurt by the malignant actions of Dwight Eisenhower, who deliberately wrecked the British economy in 1956 to stop the Suez Canal seizure by Britain, France, and Israel. The fact that he’d only squeezed the pound was still a sore spot with many Brits, and when the effect of the Vietnam War ultimately affected the British economy through shortages of materiel, the first Wilson government had to devalue the pound, which helped spur the current inflation. Twice in the past twenty years, America had used its might in ways devastating to the British economy, and they demanded fealty together in defence, foreign affairs, and economic decisions. Rockefeller wasn’t a bad chap, but these reasons were why Healey had turned from Benn’s position as a staunch advocate for Britain alone and free to a Britain firmly engrained in the European economy. Healey understood that relying upon America, and the IMF it controlled, was the path towards total subservience. The man with the world’s second most famous eyebrows (after the now-departed Leonid Brezhnev) would work with the Americans to keep inflation down, but he was even more keen to extricate the pound from the influence of the dollar and join arms with the French and West Germans to gain more equal footing.

Healey felt he had to win. It would be the only way to stop the unions from running the country. God help them all if Benn or Foot won. He liked them, they were wonderful conversationalists and excellent scholars, but they had no business running a nation. They had to be brought to heel, but delicately, because it was far more important to keep them in the tent, as Harold would do. Left to their own devices, they could easily bring down the delicate coalition.

*****

There was one other incident that day, one that drew little notice outside the city of Exeter where it took place. A young man, with fashionably long hair and a strong jawline, boarded a bus in the small town of Barnstaple, a port on the end of the River Taw before it meets the Bristol Channel, and rode it for two and a half hours southeast until it reached the city of Exeter. He then wandered around the city for some time. Later, witnesses would note that he seemed to be out of sorts, emotional, and in pain. He rode another bus to the other side of the recently opened junction of the M5 motorway in Clyst St. Mary, a small hamlet bordering the city, and took tea at one of those delightful English places named the Half Moon Inn, located on Frog Lane. At a quarter past four, he left the pub towards the bustling motorway, where commuters were driving home from work and the night shift was driving to work at the North Devon and Exeter Hospital on the other side, or perhaps one of the many hotels on Magdalen Road or the restaurants near the Quay. It was reaching a peak time of traffic, and the man walked along the sidewalk, moving to the grass as he reached the roundabout that diverted traffic onto the M5 or underneath it into Exeter. He stayed on the sidewalk that progressed up to a crosswalk where the offramp from the southbound side of traffic terminated at the roundabout. He thought about crossing, then continued up the side of the offramp, walking alongside the safety rail in the grass. The sun was rapidly setting now, the drivers of the vehicles on the M5 in this direction facing firmly towards the red-orange ball of light descending below the horizon. At this section, the speeds of drivers ranged from 50 mph (those who wished to save on petrol) to 70 mph (the national speed limit for motorway drivers). With tears running down his face, Norman Scott walked right in front of a lorry changing lanes for the offramp. He died instantly upon impact.

Five platoons of four Cheyennes each were fueled up, loaded up, and lifted off at dawn, heading northeast towards the NVA encampment. There was a mix of armor, artillery, some SAMs (much had been expended against the RVNAF A-7s which provided support during the weeks of siege), and a lot of infantry. As the Cheyennes approached, they could see on their long-range scopes that the NVA were being a bit lazy, not having taken precautions against an air assault such as theirs. They probably think it’s all over now, one of the pilots thought. You little bastards are about to get a big surprise. The initial assault was going to be three platoons, with two hanging outside the area, ready to capitalize on the NVA’s reaction to what was coming. The main weapons were four BGM-TOW 71 missiles on the outer hardpoints, with 2.75 inch cluster rockets on the two inner hardpoints. In the nose of the Cheyenne was an M134 minigun loaded with NATO 7.62mm bullets, and a 30mm cannon attached to the belly of the chopper. Reaching the combat zone, the TOWs were fired off first, wiping out a dozen T-54 tanks and waking up the sleeping NVA soldiers as those who were near the end of their watch were jolted from semi-sleep to terrified alertness. The miniguns were used to spray the soldiers as they ran, ripping them apart with a literal hailstorm of bullets. The rockets were fired at the light-skinned PT-76 “tanks” that were really nothing more than a glorified Soviet version of a basic M113 and tore right through the thin aluminum armor.

There was a determined effort by the NVA’s 7th Infantry to get the artillery to a place of safety, and SA-7s were hoisted and launched, however, the low altitude and constant movement of the Cheyennes meant that they couldn’t gain infrared lock before rocketing past harmlessly into the skies. This was an issue that the SA-7b had corrected, but the NVA were armed with surplus 7a variants, which engaged low altitudes relatively well, but only from behind, and those targets were the slower moving Hueys carrying infantry. A fast-moving attack helicopter did not meet those guidelines, and the NVA was paying a price now. After expending their missiles/rockets, and most of the 30mm cannon ammo, the first attack began peeling off, and the artillery group stopped moving for a moment, their eyes glued to the skies as the platoons of attack helicopters receded into the distance. This was a fatal, yet entirely understandable error. As the soldiers believed the assault was over, they were taking a breather, the adrenaline receding...and then the second wave of two platoons rose up over the horizon at their rear, and volleyed their TOW missiles into the artillery regiment, destroying most of the guns and virtually all of the ammunition for them. An ammunition dump was spotted by one of the pilots, and that Cheyenne banked hard left and loosed a couple of 30mm cannon rounds into it, sending a tremendous geyser of flame and smoke into the sky. Ammo dumps were rare for the NVA and Vietcong, as they believed in traveling light, but this assault on Phước Long had been with the design of creating a strategic foothold to launch the final assault on Saigon, and so they’d brought more supplies forward than the norm to supply that assault. It was all done with the belief that the Americans had left this war and didn’t care to help Saigon. Complacent, sure of rapid victory, the three divisions of the NVA lead forces had been left disorganized and without most of their heavy weaponry. The raid was completed with not a single helicopter shot down by the NVA forces, too stunned by the appearance of these new, larger helicopters with the ability to destroy T-54s from the air. The remnants were soon driven back into Cambodia by regrouped RVN forces that had just lost the city ten days ago. The AH-56s had all flown with the decals of the RVNAF, with nary a sign that Americans were piloting them, and when word reached Hanoi, there was great confusion as to what had happened. This was decidedly not the case in Washington, where the President was ecstatic with the results. The generals were delighted because it proved the worth of attack helicopters in this role. The CIA was delighted because they’d successfully pulled off a covert op despite the increased scrutiny they were under.

Enquiries were made by the North Vietnamese with their Soviet sponsors, who were equally as surprised. They knew from their sources that only a single AH-64 Apache helicopter had been built, and while some of the more finely tuned analysts had raised the question of the Cheyennes, the consensus from their KGB/GRU superiors was that it wasn’t possible, because the Americans hadn’t built that many, and some had already gone to museums. A coded signal was sent to a deep cover KGB officer in Florida, who drove up to Tallahassee, meeting a lovely young woman in her junior year who was active in the remnants of the peace movement on the campus of Florida State. He asked her to please have her boyfriend, a low-level draftee at Fort Rucker, check to see if they still had the AH-56 on display outside of the aviation museum there. The cover story the KGB man provided was that they’d [the peace movement] heard a rumor that the South Vietnamese bought them to use in the war. The private first class went over to the museum after the end of his duty schedule for the day, and saw an AH-56 sitting on the lawn, just as it had been. Now, being a young man only twenty years old, he didn’t look too closely, and so therefore did not observe that what sat on the lawn was an aluminum fabrication, with iron ballast inside the shell to keep it weighed down. The CIA had thought their deception through, and recognized that the sudden disappearance of museum pieces around the country might be noticed, so basic models were fabricated that would fool any casual onlooker, because who took time to inspect a museum piece that was on the lawn and roped off? When the KGB received confirmation that the AH-56 was still in its museum location, they eagerly informed their GRU comrades, and the North Vietnamese, that whatever it was, it wasn’t American. This bravado was misplaced, but hardly surprising. The opinion of the world was that America, in general, was in decline. It was the same for France, and Great Britain, the old Allied powers were all in economic malaise, trying to fight off inflation, beset by labor problems, and unable to wield power as they once had.

A President less self-confident than John Connally likely would’ve limply asked Congress for aid, and not tried any sort of covert action after the impeachment and conviction of their predecessor, but John Connally was a man of action, and he’d decided months ago that he would not take North Vietnam’s complete abrogation of the treaty they signed lying down. Congress would probably start squealing whenever the world figured out that America had supplied wonder weapons to the RVNAF, press the administration on the issue, call Nitze up to the Hill to testify. Nitze would tell them that it was better they be used helping an ally than gathering dust in a museum. Marvin Kalb would issue a statement from the White House that it was the duty of the nation to enforce treaties it was a signatory to. What would Congress do? Throw a tantrum and start a bunch of investigations about twenty helicopters? Connally doubted they would want to drag America through that again, and unlike Dick, he didn’t waver back and forth, needing handholding to make his decisions. He’d run through his options, decide on the best one, and take action. If the South could hold out and force a stalemate, Connally had already discussed with Clements the idea of offering a discounted production run of more to assist in their defense. It’d keep the Lockheed factories running longer, and that was just good economic sense. As it was, the last ten that had been paid for by the reprogrammed Pentagon funds were in production now, and would be over there soon enough. The A-10 was about to start a production run for advanced testing prior to acceptance. If the Republic of Vietnam made it to 1976, he’d sell some of the A-10s to Thieu, have the pilots from the RVNAF go to Thailand, or to Clark AFB in the Philippines, learn how to fly them, and then take delivery and fly back to Saigon. Americans didn’t have to fight themselves to hold the South, not with new weapons and aircraft that the NVA were ill-equipped to fight. These were precision weapons, able to be flown at the treetops or lower, armed with far more firepower than the Huey Cobras with their miniguns and singular rocket pod.

Twenty helicopters had completely stalled three divisions of infantry and armor. The shape of war was changing again.

*****

In Long Beach, an odd ship was leaving port for the second time. It wasn’t quite a container ship, not quite an exploration vessel. The Hughes Glomar Explorer was, publicly anyway, designed for the mining of manganese nodules on the floor of the Pacific Ocean. It was an odd quest, but Howard Hughes, the titular builder of the ship, had long been known for his odd interests, and so nobody was surprised by the announcement, as it was perfectly in character for the man.

Mining was not what the Glomar was built to do. It was purpose-built for one task: to recover the remains of a Soviet Golf-class nuclear missile submarine known as K-129. In 1968, the Golf had suffered a catastrophic failure of unknown origin and sank to the bottom of the Pacific while sitting outside one of the routes into Pearl Harbor used by the United States Navy. The USS Halibut, an early-generation nuclear attack sub fitted with special equipment, was able to get a camera down to the ocean floor where it laid, and Richard Nixon had approved the Glomar’s mission and building in 1970. Right after the conviction of Nixon by the Senate, the massive ship had left Long Beach for its first attempt to raise the sub. However, during a test run with the large grabber hand its crew had named Clementine, several of the large steel fingers had broken badly. As the ship was not too far along in its journey, the decision was made to return to port for repairs. While the engineers examined it, they determined that the fingers, while very strong, did not retain flexibility under sea pressure, and that was why they broke off. It took another six months to manufacture fingers with a new composite steel, which was tested repeatedly and determined to be sufficient for the task. This trip, unlike the first one, did not draw the same sort of curiosity as the first launch, and was done at night to escape prying eyes. This included the Soviet “fishing trawlers” that were used to spy on U.S. military operations worldwide. The Glomar took a leisurely path over the next two weeks to Hawaii, moving at their limited maximum speed of ten knots, arriving on February 2nd. What transpired during the next five days would become the subject of heated debate when the story became public months later.

*****

Three days after the Glomar Explorer arrived at the wreckage of K-129, British Prime Minister Harold Wilson rose to give his opening statement during Prime Minister’s Questions. Mere minutes before, a letter had been delivered to Her Majesty informing her of the bombshell he was about to drop in front of Parliament: the announcement that he would resign as soon as a successor could be chosen. He stated that he was experiencing health issues that rendered him unsuitable to continue as the leader of Her Majesty’s Government. Wilson stated that he would not back any candidate, as he wanted the vote to not be influenced by how he felt, but how the parliamentary party felt. He stepped down from the rostrum, and Edward Heath, his longtime foe, a man who simply could not stand Wilson’s smoothness with voters, stood up to speak. Heath, for all of his quirks, was at heart an honorable man. One civil servant at Number Ten said of him, “I like Mr. Wilson and I always got on smashingly with him. He knew how to talk to people, but I never could quite trust him. Mr. Heath was not good with small talk, but I absolutely trusted him. I’ve never met a man with the sort of integrity he has.” So, upon his rising, he spoke of his sadness that Wilson was suffering from health issues and hoped that he could, through treatment, continue to lead a long and enjoyable life. Heath added, “Though he bested me more times than I care to admit, he has served his country honorably for many years, and his support as we approach the European Community referendum has been most appreciated. That project has been closest to my heart for two decades, and the fact that a political adversary such as he could throw his support behind an issue that his opponent has championed for so long speaks volumes to his character. I thank you, Prime Minister, and I wish you a well-deserved retirement.”

The rarest of moments from the past decade occurred then, as the Labour benches rose at one to applaud the statement, with many of the Tories doing so as well. Not everyone cared to rise. Certainly Margaret Thatcher did not. The dour look on her face stood out amongst the more jovial, or sad, visages of the others around her. Enoch Powell looked pleasant enough as he provided a mere golf clap for Wilson. He was in quite a unique position, because he hated both Wilson and Heath; Wilson for his politics, and Heath for exiling him to the backbenches. Both he and Thatcher were potential rivals to challenge Heath for leadership of the party, for nobody had survived in leadership of the Conservative Party with the electoral record of Heath. Even Clement Attlee, though many forgot, had won twice as leader to his three losses for Labour. Had Heath done just a little bit better a year before, there wouldn’t be a Lab-Lib government, for the Tories drew more votes, but not enough seats for a majority. In a sense, he had won, but not well enough.

On the Labour side, as Wilson believed a year ago, half of his Cabinet was already polling the members to get a sense of their fortunes. James Callaghan, the Foreign Secretary, Denis Healey, the suffering Chancellor of the Exchequer, Tony Benn, the Energy Secretary, Michael Foot, the leader of the House, Tony Crosland, the very able Environment Secretary, and Home Secretary Roy (“Woy”) Jenkins were all standing. Benn represented the true socialist left of the party, Jenkins the sensible center of it, with Foot closest to Benn’s position and Crosland closest to Jenkins, while Callaghan and Healey sat between those two sides. Labour had a lot of positive accomplishments to look back on for the past thirty years: decimalization, the creation of the National Health Service, a robust economy during the latter half of the 1960s, responsible stewardship of the pound, and numerous public housing works to reduce homelessness. By the same token, the unions in Britain, stricken by inflation, had become more militant than ever before, and steadfastly refused to negotiate wages in any accordance with the current economic situation. Healey flat-out despaired of keeping the lid on the boiling pot. He was in near-daily contact with Canadian Finance Minister John Turner (a lad from Surrey, of all places!), Italian Finance Minister Bruno Visentini, French Prime Minister/Finance Minister Raymond Barre, West German Finance Minister Hans Apel, and United States Treasury Secretary Nelson Rockefeller. They were set to meet in May at Rambouillet in France, prior to the first G6 meeting of their nation’s leaders. Connally and Rockefeller had been pushing the need to keep inflation down in a responsible way so as to not trigger a recession. France had been doing the best, as Barre’s government had been investing in infrastructure, which helped workers build their bank accounts, and they’d also raised pension benefits, which helped the old and poor participate in the economy to a greater degree. The West Germans continued to chug along with innovation after innovation in the realms of automotive engineering and technology, producing excellent vehicles on par with the Japanese for fuel economy. Canada and America were joined at the hip, and Britain was muddling along, stuck in a malaise not entirely of their own making. The pullback by the French from NATO, and the lack of contribution from smaller nations towards the common defence had put more of the onus on Britain, and between the development of nuclear weapons, maintaining their strong navy, and the British Army On the Rhine, too much of their money went to defence and not enough towards investment.

The British were further hurt by the malignant actions of Dwight Eisenhower, who deliberately wrecked the British economy in 1956 to stop the Suez Canal seizure by Britain, France, and Israel. The fact that he’d only squeezed the pound was still a sore spot with many Brits, and when the effect of the Vietnam War ultimately affected the British economy through shortages of materiel, the first Wilson government had to devalue the pound, which helped spur the current inflation. Twice in the past twenty years, America had used its might in ways devastating to the British economy, and they demanded fealty together in defence, foreign affairs, and economic decisions. Rockefeller wasn’t a bad chap, but these reasons were why Healey had turned from Benn’s position as a staunch advocate for Britain alone and free to a Britain firmly engrained in the European economy. Healey understood that relying upon America, and the IMF it controlled, was the path towards total subservience. The man with the world’s second most famous eyebrows (after the now-departed Leonid Brezhnev) would work with the Americans to keep inflation down, but he was even more keen to extricate the pound from the influence of the dollar and join arms with the French and West Germans to gain more equal footing.

Healey felt he had to win. It would be the only way to stop the unions from running the country. God help them all if Benn or Foot won. He liked them, they were wonderful conversationalists and excellent scholars, but they had no business running a nation. They had to be brought to heel, but delicately, because it was far more important to keep them in the tent, as Harold would do. Left to their own devices, they could easily bring down the delicate coalition.

*****

There was one other incident that day, one that drew little notice outside the city of Exeter where it took place. A young man, with fashionably long hair and a strong jawline, boarded a bus in the small town of Barnstaple, a port on the end of the River Taw before it meets the Bristol Channel, and rode it for two and a half hours southeast until it reached the city of Exeter. He then wandered around the city for some time. Later, witnesses would note that he seemed to be out of sorts, emotional, and in pain. He rode another bus to the other side of the recently opened junction of the M5 motorway in Clyst St. Mary, a small hamlet bordering the city, and took tea at one of those delightful English places named the Half Moon Inn, located on Frog Lane. At a quarter past four, he left the pub towards the bustling motorway, where commuters were driving home from work and the night shift was driving to work at the North Devon and Exeter Hospital on the other side, or perhaps one of the many hotels on Magdalen Road or the restaurants near the Quay. It was reaching a peak time of traffic, and the man walked along the sidewalk, moving to the grass as he reached the roundabout that diverted traffic onto the M5 or underneath it into Exeter. He stayed on the sidewalk that progressed up to a crosswalk where the offramp from the southbound side of traffic terminated at the roundabout. He thought about crossing, then continued up the side of the offramp, walking alongside the safety rail in the grass. The sun was rapidly setting now, the drivers of the vehicles on the M5 in this direction facing firmly towards the red-orange ball of light descending below the horizon. At this section, the speeds of drivers ranged from 50 mph (those who wished to save on petrol) to 70 mph (the national speed limit for motorway drivers). With tears running down his face, Norman Scott walked right in front of a lorry changing lanes for the offramp. He died instantly upon impact.

Small question: Was the October '74 election butterflied in this timeline, and if so, what caused that?

The entire point of the the Lib-Lab coalition in the '74 government, was, in a sense, to bide its time until either party would be in a position to benefit majorly from an election being called; a majority government for Labour, and a Liberal cohort large enough to be able to dictate all of Labour's policy respectively. As a result, any major polling swing that would make Wilson feel safe in resigning would also more than likely prompt him to call an election to grant the party a majority as a "parting gift"to his successor - Wilson was too fierce a political animal to pass up such a chance, unless of course, his Alzhimers' had truly progressed too quickly to allow him to do so without risking larger issues for the UK.

In any case, the fact that the Thorpe affair won't ever break [or, if it breaks, it would instead be that of Thorpe's secret sexuality - damaging to him, but not the party as a whole] now that its whistleblower and focal point won't be in any position to blow the lid off certainly augurs well for the Liberals' ability to try and make the most of any post-Wilson polling shift, as much as Healey would certainly try to put pay to that notion if he has any say in it.

The entire point of the the Lib-Lab coalition in the '74 government, was, in a sense, to bide its time until either party would be in a position to benefit majorly from an election being called; a majority government for Labour, and a Liberal cohort large enough to be able to dictate all of Labour's policy respectively. As a result, any major polling swing that would make Wilson feel safe in resigning would also more than likely prompt him to call an election to grant the party a majority as a "parting gift"to his successor - Wilson was too fierce a political animal to pass up such a chance, unless of course, his Alzhimers' had truly progressed too quickly to allow him to do so without risking larger issues for the UK.

In any case, the fact that the Thorpe affair won't ever break [or, if it breaks, it would instead be that of Thorpe's secret sexuality - damaging to him, but not the party as a whole] now that its whistleblower and focal point won't be in any position to blow the lid off certainly augurs well for the Liberals' ability to try and make the most of any post-Wilson polling shift, as much as Healey would certainly try to put pay to that notion if he has any say in it.

If in fact they do, surviving South Vietnam has so many intriguing paths, including a likely one of joining Singapore as the early American computer manufacturing hub. This timeline’s iPhone is probably made outside Saigon. As I recall it took 3-4 years for the North to muster up the supplies for a major assault, stopping this one might well buy enough time that the North has to confront their economic problems instead of yet another assault south.

Great chapter, love this timeline

Great chapter, love this timeline

So, I'd written in the June 1974 entry that Wilson wanted breathing space before calling another election. The difference in OTL election is that Labour won two fewer seats and the Tories four fewer that had been won by Liberals, giving Thorpe 20 seats to bargain with instead of 14. Sharp eyes may also have noted that one Enoch Powell did not lose his seat, as per OTL, and is still about to cause mischief for the Tories.Small question: Was the October '74 election butterflied in this timeline, and if so, what caused that?

The entire point of the the Lib-Lab coalition in the '74 government, was, in a sense, to bide its time until either party would be in a position to benefit majorly from an election being called; a majority government for Labour, and a Liberal cohort large enough to be able to dictate all of Labour's policy respectively. As a result, any major polling swing that would make Wilson feel safe in resigning would also more than likely prompt him to call an election to grant the party a majority as a "parting gift"to his successor - Wilson was too fierce a political animal to pass up such a chance, unless of course, his Alzhimers' had truly progressed too quickly to allow him to do so without risking larger issues for the UK.

In any case, the fact that the Thorpe affair won't ever break [or, if it breaks, it would instead be that of Thorpe's secret sexuality - damaging to him, but not the party as a whole] now that its whistleblower and focal point won't be in any position to blow the lid off certainly augurs well for the Liberals' ability to try and make the most of any post-Wilson polling shift, as much as Healey would certainly try to put pay to that notion if he has any say in it.

So, to put it into easy to read form...

| United Kingdom Parlimentary Election Results, February 28, 1974 | |

|---|---|

| LABOUR | 299 |

| CONSERVATIVE | 294 |

| LIBERAL | 20 |

| SNP | 7 |

| OTHERS (Plaid Cymru/Democratic Labour/DUP/SDLP/Ulster Unionist) | 15 |

| TOTAL | 635 |

So, SNP agreed to join Labour in coalition for votes in the House, per OTL, giving Labour 306. A majority is 318. The Liberals pushed it up to 326 in official coalition. As a matter of practice, the UU party voted Tory, Plaid Cymru with Labour, and the others floated. In OTL, the Feb election left the Liberals without any official coalition, and Wilson led a minority government until the October election, where Thorpe hoped to push his vote share up, but instead lost one seat and was left to accept the proffered deal to boost Labour's one-seat majority in the House. SNP gained four seats in OTL, going up to 11, and joined Labour on votes as well.

HOWEVER, this does not mean they take the whip, and that, along with some other various reasons, is why Labour's government fell in 1979 OTL. Here, they have a deal with Liberals in the Cabinet--Thorpe is currently Secretary of State for Trade, Jo Grimond is Secretary of State for Scotland and David Steel is minister for overseas development (managing aid packages to other nations, forging partnerships, etc. ). With Wilson stepping down, there will be an inevitable reshuffle, and Thorpe is going to make his play for foreign secretary.

If you have Amazon Prime, watch Season 1 of A Very British Scandal.Who the heck is Norman Scott?

Hint: he was otherwise known as Norman Josiffe, depending on his mood. He was accidentally pivotal in 1970s politics IRL.

marktaha

Banned

Enoch Powell did not lose his seat but just didn't stand.So, I'd written in the June 1974 entry that Wilson wanted breathing space before calling another election. The difference in OTL election is that Labour won two fewer seats and the Tories four fewer that had been won by Liberals, giving Thorpe 20 seats to bargain with instead of 14. Sharp eyes may also have noted that one Enoch Powell did not lose his seat, as per OTL, and is still about to cause mischief for the Tories.

So, to put it into easy to read form...

United Kingdom Parlimentary Election Results, February 28, 1974 LABOUR 299 CONSERVATIVE 294 LIBERAL 20 SNP 7 OTHERS (Plaid Cymru/Democratic Labour/DUP/SDLP/Ulster Unionist) 15 TOTAL 635

So, SNP agreed to join Labour in coalition for votes in the House, per OTL, giving Labour 306. A majority is 318. The Liberals pushed it up to 326 in official coalition. As a matter of practice, the UU party voted Tory, Plaid Cymru with Labour, and the others floated. In OTL, the Feb election left the Liberals without any official coalition, and Wilson led a minority government until the October election, where Thorpe hoped to push his vote share up, but instead lost one seat and was left to accept the proffered deal to boost Labour's one-seat majority in the House. SNP gained four seats in OTL, going up to 11, and joined Labour on votes as well.

HOWEVER, this does not mean they take the whip, and that, along with some other various reasons, is why Labour's government fell in 1979 OTL. Here, they have a deal with Liberals in the Cabinet--Thorpe is currently Secretary of State for Trade, Jo Grimond is Secretary of State for Scotland and David Steel is minister for overseas development (managing aid packages to other nations, forging partnerships, etc. ). With Wilson stepping down, there will be an inevitable reshuffle, and Thorpe is going to make his play for foreign secretary.

March 1-4, 1975

By their very nature, leadership battles for the top seat of a political party are brutal affairs, and become more so when the office of Prime Minister for the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland is involved. The resignation of Harold Wilson, perhaps the most dominant figure of the past decade of politics, opened up a bloodbath of a battle for the top spot. Very early on, Michael Foot recognized that he lacked the photogenic appeal that modern leadership required, and threw his backing behind Tony Benn, his closest ideological partner. This gave Benn a very strong base of votes to draw from, and while some of Foot’s backers withdrew for Denis Healey or Tony Crosland, after the first ballot, it was James Callaghan in first, Benn in second, and Roy Jenkins a fairly distant third. Crosland and Healey were eliminated, and the second round of balloting would be between Callaghan, Jenkins, and Benn. Healey backed Callaghan, and Crosland threw in with Benn. Jenkins could not move his margins. There were only so many centrist Labourites in 1975, and he’d maxed out the support he could expect to get. This left Jenkins with a dilemma. He loathed Benn, but was very close with Crosland (they’d been homosexual lovers decades ago, something both men worked hard to obscure). It made Crosland’s decision to side with Benn even more painful, and Crosland explained it as a matter of bringing things to a close before it dragged out too long. He bluntly told Jenkins that, despite his aspirations and his talents, his policy positions simply would not, could not win. Even if he and Healey both gave their support to Jenkins, it would simply allow him to draw even with Benn. A stalemate would be the result that nobody wanted. He suggested that Jenkins should consider that he held the election in his hands. He could force a stalemate, which would leave Wilson to stagger on in a position he needed to leave, or he could decide the outcome. Crosland knew that there was absolutely no way Jenkins would support Benn, but he could put Callaghan over the line, and Crosland would still be rewarded because he was widely considered to be the finest mind the party had.

Jenkins went home depressed. He spoke with his surrogates, who’d been out trying to whip up support amongst the rank and file, and one of them said he’d visited some of the miners’ union officials, and when asked if they’d back Jenkins, the response was, “Nay, lad, we’re Labour men to our core. Roy Jenkins only is one when it suits him, and he’s a Liberal when it doesn’t.” The Home Secretary sat in semidarkness in his living room, a drink in his hand and a cigar in his mouth, considering his options going forward. He wanted Foreign Secretary, but Thorpe was going to make a play for it, and the Liberals were crucial to keep onside. Jenkins was tired of being Home Secretary, tired of dealing with prisons and police and all the domesticity. His passion was Europe. In this he was very much like Ted Heath, though Jenkins could never be a Tory with his libertarian social mindset. He had affairs with the wives of his colleagues, and an arrangement to where his wife essentially approved of them. There was the possibility of Defence, but that was not particularly exciting for him, too much like Home Secretary, but at least he’d be more involved with Europe. He also did not want to return to the Exchequer. He could maybe get appointed to the European Commission, leave Britain and all its sordid smallness behind. It would essentially be the end of his involvement in elected politics for the rest of the decade, though. The line from the miners kept playing in his head, until he recognized the truth in the insult. Where he was these days was far from where Labour was. Why not join the Liberals? They held the balance of power, and surely after a time he could maneuver Thorpe out of the way. Their positions were closer to his now than he was to his government’s positions. He felt bad about the effect it’d have on Crosland, but Tony would understand, right? There was no sense in staying where one was not wanted.

He’d wait until after the vote, though, to see how things settled. Perhaps he’d get an offer he couldn’t refuse, just like that mafia movie he’d seen, and could stay in Labour. Perhaps.

Two days later, after a quiet meeting with Thorpe and another one with Callaghan, Jenkins announced that he was supporting “Big Jim” and asked his voters to swing to Callaghan, which they did with alacrity. Benn picked up no further support, while Callaghan sailed across the finish line with 172/299 PLP votes. Benn later would wonder if he’d been set up somehow by Crosland, but Crosland was so kind to him afterwards that he decided he couldn’t have done this maliciously. The former Lord was now left to ponder his future. He wanted a different Cabinet spot than the technocratic ones he’d been given up until now, and he felt his showing deserved something better. Industry, Technology, Energy. Tony Benn was about people at his heart. He definitely felt that he should be Deputy Leader of the party, because he was the tribune of the Left, and the most beloved amongst the rank and file. Callaghan, meanwhile, was trying to come up with reasons to not select Benn. He thought the man was ego run amok, completely incapable of being a team player. Foot went to have dinner with Callaghan at Number Ten the night after he moved in. The sartorially challenged Foot calmly explained how he was going to challenge, but he saw the way the trends were moving in politics. He pointed to John Connally as just one example, a smart man who made a point of focusing on little details with his wardrobe and his public appearances. He reminded the new Prime Minister that Benn, for all his faults, had won the hearts of the party, the unions, and a third of the Parliamentary Party, and that heart matters. “Jim, we’re going to have to call an election soon. We cannot keep going on in coalition, hoping to remain in full lockstep. Eventually, something will happen, and the Tories will pounce and defeat us on a vote. It is too slim a number to rely on. We both know keeping the SNP on our side means a devolution vote, and we’re not ready to do that: the Left does not want to split our nation up, and the Right doesn’t want to lose the naval bases there.” Foot could be spellbinding as an orator, and he was drawing upon those skills to convince Callaghan of the next steps. “The next election is going to be determined on turnout, and Tony Benn knows how to get our base of support out there, handing out our manifesto, rallying in the streets, talking to neighbors and relatives and convincing them that we are the way forward through all of the trials ahead. You don’t have to accept his every idea. You don’t have to use his personal beliefs as the solution for our ills. I am not convinced that his economic plans to beat inflation are sound, but Jim, if you keep Denis at the Exchequer and do not have the party base in leadership, we’re going to make people yearn for Heath’s three-day week.”

Callaghan let out a deep sigh, his substantial frame rumbling a bit as he did. “I’ve gotten enough advice to write a newspaper column for a year, Michael. If you could choose, what would you do?” Foot pulled a piece of paper from his jacket. “Jim, I thought about it since the final vote. Our biggest issue is sharing positions with Thorpe’s party. This is part of why we truly need to hold a new election. We need a majority so we don’t have to keep them happy, but for now, until then, we must face the reality that their happiness is the only thing preventing a vote of no-confidence. For now, here is what I propose, in keeping with Harold’s maxim that we mustn’t divide the Party.”

Benn-->Employment and Deputy Leader

Healey-->Home Office

Crosland-->Exchequer

Thorpe-->Foreign Office

Grimond-->Scotland

Jenkins-->Defence

“You can shuffle the rest as you wish, Jim, but to me, this seems to be the best way to keep everyone onsides. It keeps Thorpe happy until we can hold an election, and frankly the man’s stance on apartheid and bigotry is splendid. Denis will do well at the Home Office, a strong hand to watch over MI-5. Tony Crosland is one of our best minds, and I believe as an economist a much better choice to sail us through the tough economic waters than Denis. Roy will want the Foreign Office, but we have to protect our coalition, and Defence is the closest thing to having that time in Europe he loves. He can go visit our bases there and East of Aden, have a jolly good time, build relationships with host nations, the sort of thing he loves. I’ve heard whispers he’s thinking about joining Thorpe’s crew or quitting altogether. He hates the Home Office. No excuse to travel. Defence should keep him relatively happy, and if you wish, you could give him the Foreign Office should we win a majority.” Foot sat back, the paper lying on the table between the two of them. Callaghan thought it over, and except for making Benn his deputy, he really couldn’t argue with any of these choices. Michael really did have a first-class intellect, thought the one man who had not gone to university yet had beat them all to the post. Then he frowned. “Michael, just one thing: where’s your name? Don’t you want to be in Cabinet?” Foot smiled his awkward smile and said, “I thought you’d never ask. Leader of the Commons. That’s what I want. That’s the soul of a government of the people. That’s where my love lies.”

He’d have to work out the rest, Callaghan thought, but this was a good way to balance the wings of the party in the top spots while keeping Thorpe from breaking the Lab-Lib Pact. So long as Benn knows his place, we’ll be fine.

*****

There was another meeting taking place across London at the Carlton Club, the legendary Conservative private club on St. James Street. It’d been called by William Whitelaw, the deputy leader of the Conservative Party. A number of the shadow cabinet members were present, including Lord Carrington, Norman Fowler, Keith Joseph, and, most importantly, Margaret Thatcher. That statement was nothing to do with her rank, for she sat below many of them, and her gender was still a detriment in these political times (she was the only female to have been invited for associate membership at the Carlton Club after she became the first female Tory Cabinet Secretary), but her importance came from her willingness to be a stalking horse against Edward Heath. Heath had lost too often, and even as Prime Minister, it was almost an accident that he’d won. The vote swing had been so drastic as to defy even the most optimistic Tory outlook, an aberration best illustrated by the swing back in 1974. Clearly, Heath had little effect on the electorate, so his leadership was rapidly considered to be on its deathbed. The question was, who would hold the pillow over its face?

That discussion was underway when another member appeared, one who’d been vilified and castigated by many in his party and around the nation, yet held great popular appeal. He was no longer a Tory, but rather an Ulster Unionist—Enoch Powell. He’d never forgiven Ted Heath for sacking him after the infamous “Rivers of Blood” speech, because he never meant it in the way that so many claimed he had. Powell raged in private that it was one thing to be against high levels of foreign immigration and quite another to be a racist. Even those on the other end of the political spectrum, such as Denis Healey, remembered quite well the moral force Powell had brought fifteen years ago after the Mau Mau massacre in Kenya by colonial troops, where he’d fiercely condemned the choices of slave labor or death used against black partisans. Powell had put it in no uncertain terms that, irrespective of the location it takes place in or the race of the people involved, dissent never justified the use of enslavement, torture, and extrajudicial murder. Healey would call it the finest speech ever rendered in the Commons, and when he’d finished, Powell had tears in his eyes. He thereby resented how quickly people judged him and had banished him from so many places. He also appreciated how Thatcher had recommended to Heath that he not sack Powell, that if he let it cool down and thought it over, it would be better for all involved. They did not personally like each other much, for he was something of a chauvinist, but they agreed on monetary policy and had a healthy skepticism for Europe. She continued to push to stay in the EEC as a way to better open the doors of trade and prosperity, while he was on the same side as Tony Benn and Michael Foot, urging a no vote. It demonstrated once again the complexity of British politics and the breadth of opinion within the various parties. Powell had left his Wolverhampton seat in the last election and stood for the UUP seat in South Down, Northern Ireland, instead. He’d urged voters in Wolverhampton to vote Labour, and said that it would be the only way to guarantee a renegotiation of terms for British membership in the EEC (plus he’d stick it to Heath by doing so—quite economical!).

Despite all of that history, inside the Carlton Club, your words and actions were safe. They would not become public, and so it was not required that the others at this table shoo away Powell. They could talk here. The drinks were served, and the discussion began. Whitelaw was loyal, and deputy leader, and he didn’t want to turn on Ted. His concern was that the party simply could not afford to have him as its head any longer. It had been quite some time since an open challenge was made to the leader of the Tories; even when Churchill was ailing during the end of his second premiership, the challenge was never in the open. This would be different. It was Thatcher (who else?) that stated what seemed to be the obvious: they could either let the old ways hold them back and suffer another defeat as soon as Callaghan called an election, or take the initiative and force change. Thatcher spoke of the need to be, as Barry Goldwater had put it across the ocean a decade ago, “a choice, not an echo.” She decried the lack of choice between the two parties right now, how on so many issues both sides supported the same outcome. Powell was nodding as she warmed to the topic, and quiet utterings of “hear, hear” were heard around the table. “Margaret, you have again made clear what so many find opaque. We are facing ruinous levels of inflation that will make it impossible for the average British family to afford housing, food, and clothing. The basics will be out of reach, and our solution, according to Ted and ‘Arold, is to turn over control to the entire continent. For the life of me, when you are so on point regarding so many of the issues facing us, I do not understand why you continue to support this monstrosity?” The mustache was twitching as Powell sat back. “Enoch, I understand your passion on this issue, but we will not survive if we cannot increase our trade, and the EEC is the one mechanism that will allow us to break down trade barriers. Those costs alone are contributing so much to our current inflation. It is only with free trade to our closest neighbors opened up that we will have the ability to bring the unions to heel. We have to show the prosperity that free trade brings to convince the people of this country to vote for us, and to vote for us on a platform where we indisputably make clear that our policy is curbing the unions and privatizing some of these nationalized industries. For God’s sake, British Leyland is about to go under, and I just know that Tony Benn is chomping at the bit to nationalize them! A thoroughly mismanaged, redundant, union-crippled company that he helped put together seven years ago, and then there was no work done in our government to close the redundant factories and help the workers train in other fields. We cannot bail out every poorly functioning company in this country, nor should that be our policy. There is a safety net, and while I find it too generous, it is certainly cheaper to pay early pensions than to throw money at keeping an utterly shambolic company afloat, is it not?” Thatcher had parried Powell’s complaints while swinging the conversation back to the mutual ground they all stood on.

“Margaret, I do not disagree with you there, but the price of open trade with Europe is to give up our national identity! To give up our sovereignty to a bunch of unelected bureaucrats in Brussels! I cannot countenance such blasphemy against our democratic traditions in this nation!” Powell’s voice did not rise much in volume, but swelled in intensity, his face becoming a bit redder as he leaned in. Whitelaw and the others were sitting back a bit, observing. Did Margaret have the mettle to fend off Powell’s attacks? In this, Whitelaw had actually summoned Powell without informing the others. He was considering running himself, but he saw potential in Thatcher that others had not, and he felt that if she could handle the intellectual strength and emotional ferocity of an Enoch Powell interrogation, she would be perfect as the next Conservative leader. The party desperately needed some backbone. Ever since Eden’s failure at Suez, there had been a quiet retrenchment, a notion that Britain had lost its ability to act independently in any great matters, and was nothing more than an appendage to America, maybe even France and Germany. The thought of that offended those present, especially Powell and Whitelaw. They had grown up with the last days of Empire, and they were none too keen on the Little England so many wanted to become. Heath, MacMillan, Lord Home, Rab Butler, all were soft about the whole thing. They wanted to assimilate and be part of some large happy multicultural European nation. They’d been in a twenty-year spiral to the bottom, cutting back the Navy, losing ground in all matters of trade, and everything acquiring a sort of dinginess to it. London didn’t shine, it was mired in a constant haze. The cities further out, Birmingham and Manchester and Liverpool, they looked like slums in New York City. Powell thought it was the full decline of Anglo-Saxon civilisation. Whitelaw saw it more as a loss of pride. Nobody wanted to succeed, to be great. Everyone just muddled along, whether it was in America or Britain or the Soviet bloc. It was as if the human race had exhausted itself, and was staggering towards extinction. Those sitting around this table were those who were tired of slouching towards Bethlehem, to use Joan Didion’s acidic phrase, and wanted to rouse their nation to greatness once more. It was a trait they admired in President Connally and Vice-President Reagan (even though the latter was largely considered to be an amiable dunce by most of them, he shared their view of the world), the view that all was not lost and America could be roused from the doldrums it’d fallen into by underestimating the Vietnamese.

As the battle raged on in front of him, Whitelaw was heartened that Margaret had come prepared, with facts and figures on the edge of her fingertips. She’d also clearly been working on her speaking voice, coming across as more assured and less shrill. Even Powell was finding it difficult to parry back her arguments. Relentless and remorseless, Whitelaw thought. She is sure of herself and holds her ground. Had she come along sooner, she could’ve stood toe to toe with Wilson. I think she’s ready. Just need to convince the others.

*****

Ronald Reagan loved California. He loved its vast expanses of open land, its clean air (where he lived, mind you, not in the cities where the smog was ruining the air quality), the ocean, and his horse farm. Rancho del Cielo, “Ranch in the Sky,” sitting high in the mountains above Santa Barbara and the California coastline. But, before he could do that, he had a speech and a fundraiser in Sacramento this Tuesday afternoon, where until last summer he was governor and resided in a leased house, a beautiful mansion at 1341 45th Street, as the governor’s mansion proper was in desperate need of retrofitting after years of withstanding a variety of natural disasters. For this trip he’d be staying at the legendary Senator Hotel, which was closer to the east entrance of the California State Capitol than the distance from home plate to Fenway Park’s Green Monster left-field wall. The Senator had seen presidents, governors, legislators, lobbyists, prostitutes, affairs of state and affairs of the flesh. Its colorful history was well-documented, and Reagan was familiar with it. The Secret Service also had institutional history with the Senator, and felt comfortable providing security there.

The other side of familiarity is that it makes the task of a predator easier. When their prey time and again follows a routine, it is simply a matter of the predator lying in wait adjacent to the routine movement. For Lynette Fromme, this meant the corner of L and 12th Streets in Sacramento, just outside the entrance where the powerful of America traversed en route to meet others at the state capitol. She wore a red dress and a red cape around it. Underneath the cape, ostensibly to protect against February’s cooler temperatures and winds, Fromme held an old Yugoslav copy of the old Soviet Tokarev TT-33 pistol, a model known as a Zastava M57, using a 7.62mm bullet, 8-bullet cartridge, very simple to use and maintain. It was basically designed for idiots, or so went the stories about old Fedor Tokarev’s words when he finished creating it for the Red Army in 1930. The TT-33 itself was derivative of the popular Mauser C96 pistol, which was found everywhere during the first World War and the Russian Civil War. One thing that Tokarev did when creating his new pistol was to increase the pressure inside of the 7.62mm cartridge, so that the velocity and striking power was increased despite the size being the same as the old Mauser round. When paired with the copper jacket the Soviets developed, the bullet also gained dangerous ability to ricochet off of hard targets. The copper jacket also meant that the bullet was considered armor-piercing by the ATF, and while some limited export of the M57 had taken place since Tito’s break with the Soviets, the bullet was banned, and the lower pressure Mauser rounds were sold with it in America.

Ms. Fromme, however, had come across a cartridge filled with the copper rounds, supplied by a friend within the broad, loosely connected “revolutionary community” in America. The KGB had made a habit during the worst of the racial conflicts of running guns to the more radical groups, and pistols like the M57 were perfect, since they were already exported in limited number to the West. When married to the original Tokarev rounds, they were quite deadly. And now, with Vice-President Ronald Reagan and his wife Nancy in town to fundraise for the Republican party, Lynette Fromm had the opportunity to strike a blow for the failed revolution of her mentor, the man she still worshipped, Charles Milles Manson. She’d tried to get access to him at Folsom State Prison after his death sentence had been commuted by the Supreme Court’s 1972 decisions in Furman v. Georgia and Anderson v. California. At the time of her repeated attempts to do so, Ronald Reagan was still governor of California, and his hardline approach to parole and prison privileges meant there was no chance that “Squeaky,” as Manson had named her, would be allowed within a thousand yards of the murderous cult leader. Lynette was the true believer of the original Family. She believed in Charlie when others had left or abandoned him. She believed in their goals of ascension and paradise, the pseudo-religion that Manson used to justify his actions. She led the remnants of his followers, the ones who were not charged and convicted, and they’d currently taken to wearing red robes and headwear, simulating that of nuns, and explaining that they were in religious training. That was the thought process behind her attire, modified to draw less attention from cops and Secret Service. She almost looked like a normal young woman, with a hint of makeup and lipstick to go with her dress and cape. She’d pulled a successful “creepy-crawly,” as they used to call it at Spahn Ranch, the day before: an advance man for the Reagan visit had accidentally left a copy of his embargoed schedule on a hallway table outside of the hotel’s ballroom, and she swiped it and snuck out without being seen. She knew where the Vice-President would be and when he would be there.